Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kazdin+Wicked Problems

Uploaded by

jenna ibanezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kazdin+Wicked Problems

Uploaded by

jenna ibanezCopyright:

Available Formats

APA PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS

Psychological Science’s Contributions to a

Sustainable Environment

Extending Our Reach to a Grand Challenge of Society

Alan E. Kazdin Yale University

Climate change and degradation of the environment are The purpose of this article is to urge that we extend

global problems associated with many other challenges these contributions by fostering behaviors that will sustain

(e.g., population increases, reduction of glaciers, and loss our environment. The article begins with a characterization

of critical habitats). Psychological science can play a of psychology, with attention to the diversity of our subject

critical role in addressing these problems by fostering a matter and the strengths and challenges this diversity offers

sustainable environment. Multiple strategies for fostering a in establishing who we are and what our science does.

sustainable environment could draw from the diversity of Climate change and many associated problems now facing

topics and areas of specialization within psychology. Psy- us will require multiple strategies from many disciplines.

chological research on fostering environmentally sustain- Yet many areas within our own discipline could make

able behaviors is rather well developed, as illustrated by unique contributions.

interventions focusing on education of the public, message

framing, feedback, decision making, the media, incentives Characteristics and Structure of

and disincentives, and social marketing. Other sciences Psychology

and professions as well as religion and ethics are actively

involved in fostering a sustainable environment. Psychol- Diversity of Our Subject Matter

ogy ought to be more involved directly, systematically, and An enormous strength of psychology is the diversity or

visibly to draw on our current knowledge and to have heterogeneity of its content areas. That diversity is evident

palpable impact. We would serve the world very well and in many ways. Teaching introductory psychology is a chal-

in the process our discipline and profession. lenge in part because so many different and seemingly

Keywords: presidential address, psychological science, unrelated topics must be covered (e.g., sensation and per-

sustainable environment, climate change ception, cognitive neuroscience, development, personality,

interpersonal relations, psychotherapy). These varied top-

A year in the presidency of the American Psycho-

logical Association (APA) does not confer any

special wisdom or brillance on the topics of our

field. There are perspectives one acquires that capture a

moment in time and provide a verbal photo, touched up—if

ics do not easily lend themselves to a connecting theme or

principle. Moreover, many topics in psychology (e.g.,

Editor’s note. Alan E. Kazdin was president of the American Psycho-

logical Association (APA) in 2008. This article is based on his presidential

not heavily doctored— by cognitive heuristics, the limita- address, delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, at APA’s 116th Annual

tions of one’s experience and knowledge, and the issues of Convention on August 15, 2008.

the times. Even so, the photo is useful when viewed in the

context of the other photos in the album, to wit, the other Author’s note. This article was facilitated by the conceptual and vision-

ary addresses of many past APA presidents, only some of whom could be

presidential addresses over the years.1 acknowledged in the body of the text. I am grateful to Susan Clayton,

At this moment in time, unprecedented advances and Anthony Leiserowitz, and Paul Stern, who provided thoughtful reviews

challenges characterize both psychology and society. In and comments on an earlier version of the article, and to Steven Breckler,

psychology and of course other sciences as well, remark- whose conversations with me contributed in multiple ways to the article’s

content, thrust, and focus.

able advances in the understanding of human functioning Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alan

have emerged. These come at a time when there are major E. Kazdin, Department of Psychology, Yale University, P. O. Box

challenges facing the world. Of course, there are always 208205, New Haven, CT 06520 – 8205. E-mail: alan.kazdin@yale.edu

challenges facing the world, but an urgent one facing

1

humanity now is the degradation of the environment on a In footnotes throughout the article, I make references to other APA

presidential addresses to convey contexts and recurring themes. APA

global scale. Psychology’s contributions to society have began in 1892 with our first president, G. Stanley Hall. The presidential

been remarkable already, but there are new opportunities to addresses from our inception to the present are available online at http://

extend our reach. www.apa.org/archives/apapresadd.html.

July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist 339

© 2009 American Psychological Association 0003-066X/09/$12.00

Vol. 64, No. 5, 339 –356 DOI: 10.1037/a0015685

disciplines relate to each other. Boyack et al. used multiple

quantitative mapping techniques drawing on 1 million jour-

nal articles, over 7,000 journals, and more than 23 million

references to identify clusters of disciplines and their in-

terconnections. Seven hub disciplines emerged: chemistry,

earth sciences, mathematics, medicine, physics, psychol-

ogy, and social sciences. The emergence of psychology is

noteworthy indeed. Psychological research is cited by sci-

entists in many other disciplines. The penetration of our

field into many other areas, especially other social sciences

and medicine, is another way in which we are drawn on by,

but also blend into, other areas.2

In a related vein, we are increasingly involved in

collaboration with other disciplines. In general, collabora-

tive or team science and multisite and multinational studies

have increased (Cacioppo, 2007; Kliegl, 2008). Years ago,

research was characterized more by an individual investi-

gator working in his or her lab with programmatic research.

This model remains important. However, collaborations

Alan E.

Kazdin involving multiple disciplines are more common now.

Photo by Joel Benjamin Moreover, the impact of collaborative papers, as evaluated

by citation data, is greater than the impact of papers pub-

lished by individual researchers (Wuchty, Jones, & Uzzi,

2007). Collaborations in science have increased in part

sports, applied and engineering psychology, social justice, because of increased specialization required in research. In

military psychology) are often omitted from introductory psychology, for example, neuroimaging and genetics re-

courses. If they were included, it would be even more search often involves collaborative teams not merely be-

difficult for students or experts to find an intuitive concep- cause of the substantive focus of the questions but also

tual vector that captures what psychologists do. because of the methodological expertise required.

The diversity of our field is also evident in the settings It is excellent that we are one of the sciences that

(e.g., industry, hospitals, schools, universities, private prac- consistently emerges as a hub discipline and that we are

tice offices, the battlefield), the populations (e.g., from drawn into many other areas and collaborative relation-

infants to the elderly; athletes, college students, astronauts, ships. We should celebrate our widespread relevance. Be-

airline pilots, and community samples; and diverse and yond celebrating, we should capitalize on the many poten-

multiple species), and the levels of analysis (e.g., from tial contributions we could make. There are opportunities

molecules to culture, from individuals to groups, and from we could seize to contribute more to society and in the

neural to social networks) that characterize our work. For process to our profession.

example, memory, one of our core topics, encompasses

research on molecules and brain regions, human and non-

human animals, and laboratory and applied work with Recognition of Our Science

individuals and larger groups (e.g., juries). This richness, to

The public as well as policymakers do not consistently

an outsider, could easily make it difficult to consider these

recognize our science. The challenge for public recognition

as topics within a given field.

is illustrated by the dominance of nonscientific depictions

Our diversity is further evidenced by our ability to

of psychology in everyday life. Pop (and mom) psychology

fuse with and diffuse into many other disciplines and fields.

books, talk show hosts, Web pages, newspapers and mag-

Examples include health (health psychology), aging (be-

havioral gerontology), and business and industry (industrial azines, and other media (from blogs to sitcoms) often

and organizational psychology). New, combined, and hy- convey stereotypes about mental health, personality, child

brid areas of specialization have emerged. Examples in- rearing, happiness, criminal behavior, relationships, and, in

clude neuroeconomics (neurobiological models of decision general, the commerce of everyday life. It is near to im-

making, choice, and risk in social and economic contexts) possible to suggest that we have a remarkable scientific

and social neuroscience (biological underpinnings of social base for understanding these topics. Indeed, against the

interaction). These combinations convey the reach of our backdrop of a vast desert of psychobabble, the normally

science.

Psychology has been identified as a hub discipline, 2

Two decades ago, Fowler (1990), in his presidential address, noted

that is, a field from which other disciplines draw (Boyack, that psychology serves as a core field for other disciplines, particularly the

Klavans, & Börner, 2005). The designation reflects how social sciences, foreseeing our hub discipline status.

340 July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist

unacceptable anecdotal case study sometimes looks like a combine and mix to help us investigate and understand emer-

methodological oasis.3 gent and enduring challenges such as terrorism, effects of

We ourselves contribute to the problem by sometimes national disasters, abridgment of human rights, and uses and

giving personal opinions based on a favorite conceptual abuses of the Internet, inter alia.

model without providing any genuine empirical support. Psychology’s contributions to society have been an en-

We are unwittingly (and perhaps sometimes wittingly) used during theme in our history. Two key points have dominated:

by the media—put a microphone in front of us, seat us in (a) Psychology has a responsibility to contribute to key social

a comfy chair on a major TV network, and give us a trick issues, and (b) we have made significant contributions already

essay question (“What were these children trying to express (e.g., in education, health care, business, and industry).6 Often

by their violence?”) that has to be answered in 20 seconds. these contributions are so deeply embedded in everyday life

In these situations and others, sometimes opinions, expe- that psychology is not identified as their origin. Tacit influence

rience, misinformation, and research findings are indistin- is quite fine—actually my personal preference— but not al-

guishable. Such imprecision can damage our credibility by ways a strong base from which to convey that we have

obscuring our knowledge base, the methodological under- something palpable to contribute.

pinnings of our findings, and—a critical facet of science— We are in a clear position to extend our reach to

the ready acknowledgment of what we do and do not know.4 address multifaceted critical issues and have further impact

Public policymakers do not reliably recognize our on society. APA is the largest organization of psychologists

science either, and that can limit our ability to help society.

For example, in the United States, the American Compet- 3

itiveness Initiative (Domestic Policy Council, Office of The frustration inherent in how our field is presented has a long-

documented history among APA presidents. Poffenberger (1936) la-

Science and Technology Policy, 2006) is designed to en- mented the fact that occasionally “we permit psychology to be sold to the

sure that the United States retains economic and leadership public by amateurs and charlatans” (p. 13). Before him, Jastrow (1901)

strength in the world. Scientific research is seen as the warned of “newspaper science” and noted how the layman cannot be

means to achieve these strengths. Stated more succinctly in expected to distinguish that from our research (p. 15).

4

As Fox (1996) noted in his presidential address, some colleagues

the Initiative’s report, “Research pays off for our economy” “elevate the trivial, . . . glibly generalize from unique to bizarre particulars

(p. 4). The report illustrates how research leads to technol- to broadly applicable principles of conduct, or . . . spew forth a kind of

ogies that improve the world (e.g., telecommunications, nonsensical psychobabble that confuses issues and encourages forms of

fuels, and energy). Related to the report and the impetus thinking or attribution that may well be worse than simple nonsense” (p.

leading to it, federal funds are targeted to projects designed 780). Before Fox, Anastasi (1972) in her presidential address noted how

the failure of psychologists to distinguish research from individual values,

to advance science and math education and the number of beliefs and preferences “diminishes credibility, arouses public skepticism,

science teachers. The education focuses on science, tech- and weakens the potential contribution of psychology to the solution of

nology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. At first social problems” (p. 1094).

5

blush, this sounds inspiring. I am hardly saying anything new in noting that the specialization

within psychology is laudatory. Early in the history of the APA, Stratton

Yet where is psychology in all of this? It is obvious to us (1909) reminded members in his presidential address that they ought to be

that we must be in the science part of STEM. Actually, “thankful [that our work] is rich and vital enough to permit and encourage

science in the above initiative and in STEM education in- different sects” (p. 68).

6

cludes the physical and biological sciences. Psychology is off Ladd’s (1894) APA presidential address noted that the science of

that list and on the list with other disciplines such as philos- psychology ought to contribute to “the practical welfare of mankind” (p.

18). Dewey’s (1900) address underscored the importance of applying

ophy and English. Astounding! The American Competitive- psychological science to improve educational practices and “social af-

ness Initiative is about education and learning, about training fairs” (p. 123) more generally. DeLeon (2002) noted that we have a

a work force, and about evaluating programs designed to “special responsibility to affirmatively address society’s pressing needs”

improve American competitiveness. Ironically, these are piv- (p. 425). Other presidential addresses followed calling for contributions

from psychology to everyday life in public settings (schools, hospitals,

otal topics and strengths of our science. Our science has direct prisons, industry) and in more specific areas including violence, conflict,

implications for making our country competitive as well as for criminality, and human rights (Anastasi, 1972; Miller, 1969; Seligman,

addressing a swath of other critical issues including, but going 1999; Siegel, 1983). Several APA presidents emphasized the contribu-

well beyond, fostering a sustainable environment. tions psychologists have made to society including conceptualizations of

how the world views human motivation and behavior (Miller, 1969; Tyler,

General Comments 1973). Of all psychology’s contributions, that of psychological assessment

has been singled out most in prior presidential addresses in terms of the

Our field is very specialized. One could easily lament our scope of its applications (e.g., schools, clinics, hospitals, the courts,

resulting fragmentation. Yet in light of challenges such as business and industry, the military, athletics; Hunt, 1952; Matarazzo,

fostering a sustainable environment, our diversity is strength, 1990; Terman, 1924). Just considering intelligence testing, Poffenberger

(1936) remarked in his presidential address that “this single contribution

as I illustrate later.5 Despite the specialization, or in my view of psychology will compare favorably with any single contribution from

in large part because of it, our discipline has broad relevance any other science in the number of persons whom it affects and in the

to social issues. The topics of our field are the elements of a potential and ultimate benefits that may accrue from it” (p. 28). Zimbardo

“psychological periodic table” of human functioning and (2004) mentioned many areas where psychology has had a “profound and

interaction: attachment, reasoning and decision making, per- pervasive impact” (p. 341) on society, including positive reinforcement in

applied settings such as schools and the home, psychological therapies,

ception, ethnicity and culture, motivation, learning, conflict, understanding stress and conveying its impact on life, parenting practices,

relationships, leadership, human– context relations, and artifi- and our strong involvement in human factors research and the criminal

cial, “real,” and emotional intelligence. These and other topics justice, educational, and health care systems.

July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist 341

and a steady partner with other organizations whose aim is cascading effects. The cascading effects also encompass

to improve the quality of life. For psychology more gen- problems of a different order, that is, problems that are not

erally, beyond any organization, a key question is whether directly environmental in nature. For example, increased

there are special issues or social needs now in the world food prices and starvation already are sources of political

that could profit from what we know and do. Is there a next unrest. More countries are likely to fail because they cannot

step in our contributions that could make a difference, that provide secure food, water, and political stability, and that

is needed, and to which our attentions, talents, and human leads to greater unrest (demonstrations, civil or rather not-

resources could or ought to be devoted? so-civil disobedience, and violence).9

The nature of wicked problems, as I noted, implies

Addressing the Sustainability of Our that there will be no single solution. For example, identi-

fying an alternative source of energy that minimizes pro-

Planet as a Grand Challenge duction of greenhouse gases and global warming will not

There are many grand challenges now facing us, including solve our problems. Indeed, the hope is that any partial or

global climate change, delivery of health care, crime, drug interim solution (e.g., use of ethanol as an alternative fuel)

trafficking, overpopulation, and the HIV/AIDS epidemic.7 will not actually create more problems. For example, eth-

A term occasionally used in policymaking, social planning, anol production from corn has complex consequences such

and business that captures the novel features of a grand as increasing the price of corn and other crops (e.g., wheat)

challenge is wicked problem (Horn & Weber, 2007; Rittel as more farm land is dedicated to corn. Also, the clearing

& Webber, 1973). Grand challenges, or wicked problems, of land for corn production can even make climate change

are likely to have several of the characteristics highlighted worse—agriculture as currently practiced is a high-energy

in Table 1. What we gain by referring to grand challenges and high-water-use industry. Ethanol from biomass that is

as wicked problems is clarity about the fact that they not part of the food supply, such as switchgrass (tall grasses

require novel ways of thinking in relation to problem

formulation, evaluation, and intervention strategies. 7

One might say that invariably there are such challenges. For ex-

Fostering environmentally sustainable behavior is ample, Bevan (1982) in his presidential address referred to a “catalogue of

clearly a wicked problem. Climate change and ozone de- woes . . . [including] problems of energy, mineral reserves, population

pletion are familiar points of departure to convey the key growth, aging, productivity, the economy, environmental degradation,

climatic change, [and] nuclear proliferation” (p. 1307). Population

issues and why fostering environmentally sustainable be- growth, environmental degradation, and climate change, central to the

havior is so critical. I shall emphasize climate change, but present article, remain with us along with the broader question Bevan

the scope of the problem includes several other grand raised: “The critical unresolved question of the world in which we live

challenges (see Table 2) that have diverse and dynamic now is whether its inhabitants can control their own destiny [and] . . .

preserve and improve the quality of our lives together” (pp. 1320 –1321).

interrelations (e.g., causes and effects; concomitant, syner- (An uncanny feature about reading history is that it is so often about the

gistic, and bidirectional effects; and inversely related ef- present.)

8

fects; L. B. Brown, 2008; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change includes global warming but many other changes as

Climate Change [IPCC], 2007; Speth, 2005).8 For example, well (e.g., changes in precipitation, drought, and wind; see http://www

.epa.gov/climatechange/basicinfo.html). Natural factors (e.g., sun inten-

climate change co-occurs and is intricately related to a sity) can effect changes, but of course, contemporary concerns are those

diminished food supply and more costly food. In part this resulting from human activity that have an impact on land and energy use,

is due to less arable land, temperature changes that reduce such as burning of fossil fuels, reducing forests, overpopulation, and

global harvests, and depletion of our water supply (for increased urbanization. Greenhouse gases per se are not a problem insofar

as they help keep the planet’s surface warm. Yet the increased concen-

irrigation; see, e.g., Battisti & Naylor, 2009; IPCC, 2007). tration of these gases has made the earth’s temperature higher than usual.

In addition, the melting of glaciers makes less water avail- The eight warmest years on record (since 1850) have all occurred since

able to irrigate major food sources (e.g., rivers that are 1998, with the warmest year being 2005. Ozone depletion refers to the

relied on to grow rice in China and India, the two leading thinning and loss of the protective layer that blocks ultraviolet radiation

coming to the earth. Depletion is caused by high levels of such chemicals

producers). Diminished food supply leads to increased star- as chlorine and bromine compounds in the stratosphere. The origins of

vation worldwide. Increased efforts to produce more food these compounds are chlorofluorocarbons, used as cooling substances in

lead to greater use of energy, which can increase green- air conditioners and refrigerators or as aerosol propellants, and bromofluo-

rocarbons (halons), used in fire extinguishers. Ozone depletion can have

house gases. More land can be cleared for farming (e.g., broad effects on human and nonhuman animals and plants and also

deforestation), but increased energy use (farming is energy exacerbate climate change. For example, ozone depletion leads to in-

intensive) and the loss of trees that might otherwise absorb creased ultraviolet radiation reaching the earth, which decreases produc-

greenhouse gases can increase global warming. tion of phytoplankton in the oceans. Phytoplankton are not only are part

of a critical food chain but also absorb greenhouse gases. Their loss

I have simplified for clarity but perhaps still have accelerates the accumulation of greenhouse gases and global warming.

conveyed the cascading consequences of one wicked prob- 9

Failing is a technical designation and refers to governments not

lem in relation to others (see Knowlton et al., 2007; Nick- having control over the personal security of their people; other groups

erson, 2003; Parry, Rosenzweig, & Livermore, 2005). To may play a significant role in governing or rule (e.g., tribal chiefs,

organized crime). Countries can be graded on multiple indicators (e.g.,

convey these effects, I began with climate change, but other social, economic, political, and military). Some of the criteria that com-

challenges listed in Table 2 (e.g., overpopulation) could prise these indicators include unemployment, overpopulation, political

serve as the point of departure and convey their own set of instability, and lack of sufficient food (see L. B. Brown, 2008).

342 July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist

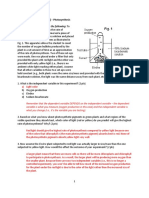

Table 1

Salient Characteristics of Wicked Problems

● There is no single, definitive, or simple formulation of the problem.

● The problem is not likely to be the result of an event (e.g., tsunami, hurricane), but rather a set of intersecting trends that

co-occur and co-influence each other.

● The problem has embedded in it other problems—including other wicked problems.

● There is no one solution, no single, one-shot effort that will eliminate the problem.

● The problem is never likely to be solved.

● Multiple stakeholders are likely to be involved, and this fact leads to multiple formulations of what “really” is the problem

and therefore what are legitimate or appropriate solutions.

● Values, culture, politics, and economics are likely to be involved in the problem and in possible strategies to address the

problem.

● Information as a basis for action will be incomplete because of the uniqueness of the problem and the complexities of its

interrelations with other problems.

● The problem is likely to be unique and therefore does not easily lend itself to previously tried strategies.

Note. These and other characteristics emerged in the context of urban planning (see Rittel & Webber, 1973) but have been extended to business, social, and public

policy and to many familiar social problems such as poverty, delivery of health care, crime, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and terrorism. The table draws from multiple

sources (Conklin, 2006; Horn & Weber, 2007; www.strategykinetics.com).

on the plains), waste biomass from nonedible parts of IPCC, 2007). The strategies will always need to be tried

plants (stalks of wheat and corn), and algae, would not have under conditions in which data are not sufficient (see Horn

some of these disadvantages. & Weber, 2007). This latter point is critical because we

Some solutions will necessarily be quite temporary, want the best data, the most pertinent data, and so on, but

albeit important, band-aids. For example, starvation in the it will always be possible to ask, “Do we really do know

world is increasing as the price of food increases. Many enough to act?” In everyday life, we are familiar with this

nations through the World Bank have injected funds to help frustrating state of affairs—a treatment for a serious disease

ameliorate urgent crises now. That is important to do, but often involves so many unknowns, including the basic one

not a solution. Some countries are purchasing land in other of whether the treatment is really effective. We do not

countries to grow products that can be shipped home for forgo treatment for ourselves or our relatives because of

their citizens. This too is a temporary “solution” for one incomplete data. Climate change and strategies to mitigate

country in which money and purchasing power are con- the change are much the same, and the luxury of complete

verted to land use and food exportation for the parent data and understanding will not be available for many

country. It is a new day. Proverbs and guiding wisdom critical decisions, but we must move forward with what we

from the past that suggest solutions now seem less appli- have. And, fortunately, we have a lot.

cable. Many of us grew up with the accepted wisdom of Psychology is a hub science for good reason—it is

“Give a man [person] a fish and he [she] will eat for a day. relevant to all those areas interested in human behavior. It

Teach him [her] how to fish and he [she] will eat for a is concretely relevant when advances are made in other

lifetime” (Chinese proverb). This inspiring expression areas. For example, fabulous medicines are of little use if

might have been applicable (a) when lakes, rivers, and people will not take them; excellent conservation ideas

streams were not diminishing in size and number, (b) when remain merely ideas if one cannot get people to adopt them;

fish were more plentiful, (c) when toxic levels of metals genetically or chemically modified products to help feed

(e.g., mercury, lead) did not accumulate in many species of the world or to feed small segments more nutritiously will

fish, and (d) before major bodies of water were contami- need to be accepted to be consumed. We can do a great deal

nated. Giving a person a fish or teaching her how to fish, in partnership with other sciences to foster behaviors that

today more readily than in the past, could be seen as a make a difference.

hostile act.

Given the complexity of grand challenges or wicked Psychological Science’s Contributions

problems, multiple solutions and strategies are needed. to Environmentally Sustainable

Even then, success may come from taming rather than Behaviors

solving the problem (Camillus, 2008). In the case of cli-

mate change, strategies will need to focus on adaptation Psychology can play an enormous role in fostering envi-

(adjustment to the changing climate) and mitigation (ad- ronmentally sustainable behaviors. Indeed, several overlap-

dressing key factors to ameliorate the causes of change; ping areas of psychology have been delineated that are

July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist 343

Table 2

Climate Change Is Related to Other Challenges and Problems

● Ozone depletion

● Reduction of glaciers

● Deforestation

● Desertification (loss of arable land for crops)

● Increase in the acidity of the oceans

● Decrease of oxygen (more “dead zones”) in oceans, lakes, and rivers

● Contamination of water and air (toxins, waste)

● Depletion of the water supply

● Population increases

● Threats to a secure food supply (e.g., grains)

● Reduced fisheries

● Accelerated rate of extinction of nonhuman animal and plant species

● Spread of vector-borne diseases (e.g., illnesses carried by mosquitoes, sand flies, ticks, and rodents) as species move into

new regions

● Loss of critical habitats (e.g., coral reefs, wetlands, rain forests)

Note. More could be added, but the list conveys the point. These problems are related to each other in complex ways, covary, and overlap. They are also

distinguishable as separate challenges and separate indices of problems related to degradation of the environment. For additional information, other sources are

readily available (e.g., L. B. Brown, 2008; Speth, 2005; www.igbp.kva.se/; www.ipcc.ch/index.htm; www.iucnredlist.org/static/introduction;

www.nature.com/climate/about_site.html).

directly relevant to fostering environmentally significant ers drink bottled water and do so in a variety of settings

behaviors, as noted in Table 3. Although these areas con- (e.g., movie theaters, gymnasiums, sports events, and of-

vey the relevance of our field, there are many additional fices). Some view bottled water as better, safer, and health-

areas that could foster environmentally sustainable behav- ier than tap water despite data that do not support these

ior and that showcase the advantage of the diversity and health claims, that show standards for regulating tap water

specialization of psychology. Among these psychological in the United States usually are more stringent, and that

subfields are media, industrial and organizational, con- reveal that bottled water occasionally is tap water (see L. B.

sumer, teaching, engineering, exercise and sport, group, Brown, 2008). In the United States, approximately 28

social, humanistic, political, peace, and family psycholo- billion plastic bottles are used to package water, and that

gies and conflict resolution, behavior analysis, human fac- requires 17 million barrels of oil. Add to that the energy for

tors, and the psychology of religion. Each area reflects shipping 1 billion bottles every two weeks from bottling

different settings, clients, perspectives, technologies, or plants to various stores and the energy used for refrigera-

points of interventions, yet each could make a difference. tion of the bottles, and the estimate is 50 million barrels of

There are many places to intervene and many topics to oil per year. If we could reliably reduce consumption of

study, and we could make this a research and application bottled water alone, the energy savings could be significant.

priority for the decade—and we should. Let me illustrate Consider another example. In hotels, people are often

some of the options and avenues for intervention. given the option of having towels changed daily or reusing

them. The energy required to wash and dry hotel towels is

Fostering Concrete Behaviors to Support a

enormous nationally and internationally. Also, detergent-

Sustainable Environment

related pollutants could be reduced by laundering less if

Illustrations. From a psychological perspective, towels were reused. Psychology can help by drawing on

it might seem that the challenge is rather clear. Behaviors theory and research to craft the message to hotel guests as

that promote a sustainable environment need to be devel- they elect or do not elect to reuse their towels. Different

oped. Perhaps we should identify and target low-hanging ways of framing the request that hotel guests reuse towels

behavioral fruit and pick them off one at a time. There are and conserve energy can make a significant difference; this

many behaviors we could address that would promote was studied in randomized controlled trials in hotels and

sustainability by saving energy and reducing degradation of measured by counting directly the number (proportion) of

the environment. guests who elected to reuse towels (Goldstein, Cialdini, &

As one example, in the United States, many consum- Griskevicius, 2008). Messages based on social norms to

344 July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist

Table 3

Areas Within Psychology That Explicitly Address Fostering Sustainable Behavior

● Applied psychology (how behavioral science can be applied to many issues and problems of society including sustainable

behavior, health, disease, and discrimination)

● Conservation psychology (how psychology can contribute to behaviors that protect the environment)

● Ecopsychology (focus on the interdependence of humans and nature)

● Environmental psychology (effects of environments on human behavior and of human behavior on environments)

● Population psychology (how population and density can impact the environment, family planning)

● Psychology of social justice (how psychology can foster human dignity, rights, peace, and security as reflected in such

areas as crime, education, civil rights, war, and globalization)

Note. Each of these areas has no single agreed-upon definition, and many of them overlap when their many definitions are considered (see Brook, 2001;

Nickerson, 2007). Thus, a list that delineates so many areas unwittingly can give the impression that there is a rather large focus on the environment within

psychology. That would be incorrect. Apart from overlap of the areas listed, each area extends beyond the focus of degradation of the environment. For example,

applied psychology includes applied: cognitive, developmental, experimental, industrial/organizational, and social psychology, each with its own graduate training

programs and career paths (see Donaldson & Berger, 2006). The areas are highlighted in the table merely to make the broader point that our field has delineated

specific areas that readily accommodate fostering a sustainable environment.

convey what other people have done are more effective lic transportation, buying food that uses few or no pesti-

than the usual nonnormative appeal. So, for example, the cides), and technology choices (e.g., using products, cars,

typical nonnormative message would be “Help save the or appliances that help or place less strain on the environ-

environment” followed by a request that guests reuse their ment) (Clayton & Myers, 2009; Stern, 2000b). These be-

towels. A social normative message, however, would sug- haviors have different costs, require different efforts, and

gest that most or some high percentage of “other guests” vary in requirements to sustain an impact. For example,

(i.e., the social norm) have elected to reuse their towels. behaviors that improve efficiency in energy use may have

The social normative message has been found to encourage an initial cost outlay (e.g., selecting one appliance rather

greater reuse of towels among guests when compared with than another, purchasing a hybrid car) but once in place do

the environmental message (44% and 37%, respectively). not require further action. We want to consider many dimen-

This effect on reuse of towels could be augmented by sions before seizing any set of behaviors as our focus.

making the normative information more specific to the Second, behaviors can have quite different impacts.

guest’s situation (e.g., other guests in this room, by gender, Perhaps worse than not helping is the illusion of helping by

and degree of concern about the environment) as opposed selecting behaviors that make little or no difference. Yes,

to a more general norm. eliminating or greatly reducing bottled water use would be

As these examples might suggest, perhaps the chal- important, but are there priorities we can identify to judge

lenge is to identify the target behaviors as a start and utilize the likely impact of such an action? For example, Gardner

our knowledge of behavior change. This task might be and Stern (2008) compared the environmental impact of

facilitated by the fact that scores of concrete behaviors have specific activities in relation to transportation (e.g., car-

been listed as actions that we can and ought to perform. For pooling, getting frequent car tune-ups, combining shopping

example, books, magazine, Web pages, and articles galore trips) and practices in the home (e.g., replacing incandes-

list many actions that help the environment and are aimed cent bulbs with compact fluorescent bulbs, adjusting the

at different age groups (children, adults) and different thermostat in one’s home for heat and air conditioning).

settings (e.g., home, business) (see, e.g., de Rothschild, Knowing the relative impact of different actions makes it

2007; Earth Works Group, 1989; “The Global Warming easier to prioritize what behaviors and practices to address.

Survival Guide,” 2007; Javna, Javna, & Javna, 2008; Third, behaviors may be important even if they do not

MacEachern, 1990). The suggestions range from concrete have a direct impact. For example, picking up litter may not

actions (using special light bulbs) to more sweeping rec- help the overall sustainability of the planet, but it can

ommendations (e.g., live more modestly). increase attention to environmental issues more generally

Nuances and complexities must be consid- and serve as a setting event or foot in the door for other

ered first. The focus on concrete behaviors alerts us to changes that do make a difference or that set the stage for

important complexities. First, there are different types of receptivity to broader governmental and policy changes

behaviors and broader influences to which we might be (Clayton, 2009; Gardner & Stern, 2002). Behaviors that do

sensitive. For example, types of behaviors include curtail- not have very much impact might foster others that do, but

ment behaviors (e.g., using less water in a shower, lowering that connection must be shown empirically. Similarly, sen-

thermostats), behavioral choices and decisions about doing sitivity to environmental issues might be increased by

something or doing something differently (e.g., using pub- making the public aware of connections they might not

July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist 345

ordinarily identify. For example, the increase in obesity in The Broader Scope of Interventions

the United States is associated with reduced car and truck

economy, leading to the use of slightly over 1 billion Many psychosocial interventions have emerged to foster

additional gallons of fuel per year (Jacobson & King, sustainable behaviors. This section is not a comprehensive

2009). This finding is not likely to have an impact on review, but it illustrates progress made and opportunities to

obesity or fuel consumption, but it might have an indirect be seized.

impact by increasing sensitivity and receptivity to change Education, knowledge, and information.

in domains that can be influenced more immediately. Em- Educational efforts are often the first point of intervening;

pirical connections and indirect impact need to be studied the long lists of behaviors in which one ought to engage is

to ensure that any impact, if present, is in the desired a simple variant of providing information about what to do.

direction. Information and knowledge alone, however, often are not

Fourth, proenvironmental behaviors are likely to be strongly related to what people actually do (Leiserowitz,

moderated by multiple influences such as values, beliefs, 2006; Nickerson, 2003). Meta-analyses reveal a low cor-

norms, networking, choice or perception of choice, and relation (approximately .30) between knowledge about en-

other factors at the individual, community, and population vironmental problems and proenvironmental behaviors

levels (see, e.g., Maibach, Abroms, & Marosits, 2007; (Bamberg & Moser, 2007; Hines, Hungerford, & Tomera,

Stern, 2000b). For example, risk perception (and misper- 1987). Information can be more effective when it is cred-

ception) is critical insofar as individual action is often ible, is combined with a commitment to act, draws on

influenced by the perceived likelihood and severity of social networks, and focuses on simple, low-cost behaviors

adverse environmental consequences stemming from that (e.g., curbside recycling; Gardner & Stern, 2002), so pro-

action (Bohm, Nerb, McDaniels, & Spada, 2001; Leiser- vision of information is not to be cast aside lightly as

owitz, 2005; Nickerson, 2003; Sundblad, Biel, & Gärling, ineffective.

2007). Individuals may see little risk to engaging in par- Education and information have an important role in

ticular behaviors or little risk that the resulting environ- part because “climate literacy” is quite low among the

mental impacts will affect them— certainly disincentives public, a situation that is driven by oversimplifications as

for action or support for strong policy actions. well as by the inherent complexities of climate change

Fifth, approximately one third of the energy consumed (Leiserowitz, 2006, in press). For example, public attention

in the United States is used by individuals and households; is currently drawn to new energy sources (e.g., drilling for

the remainder is used by business, industry, the military, more oil) as a high priority, but this “solution” ignores

and other players (Gardner & Stern, 2002). Consequently, other strategies that might be cheaper, more immediate, and

the behavior of individuals is only one level of analysis. more effective. At this point in time, the best source of

Individual behavior and group behavior can affect larger energy is not new energy (e.g., more or alternative fuels)

organizations, but achieving such an effect requires a dif- but rather better use of existing energy. The notion of a

ferent order of behavior (e.g., mobilizing grass roots move- “negawatt,” in contrast to a megawatt, refers to a unit of

ments, devising policy) that exerts influence indirectly. electrical power saved as a result of reducing demand or

In general, there are many considerations and a liter- increasing efficiency (Lovins, 1989). Energy efficiency

ature well developed to convey that while changing behav- should be a top priority, yet this message has not been well

ior is important there is more to changing behavior than, conveyed. Also, once the message is conveyed, the specific

well, changing behavior. Behavior change may come “at behaviors that have optimal impact are not intuitively clear

the end of a long causal chain involving a variety of to many of us. Similarly, the public often sees recycling as

personal and contextual factors” (Stern, 2000a, p. 525). A central to proenvironment behaviors. Recycling is valuable

direct onslaught on target behaviors may or may not be the but usually has less of a positive impact than reusing

primary, best, or only focus. Often the context may even materials, which in turn has less of an impact than reducing

preclude such an onslaught’s having much impact on spe- the amount of materials used in the first place. For example,

cific behaviors. For example, getting people to use public plastic and paper shopping bags, which require energy to

transportation or cars with alternative (nonfossil) fuel is not fabricate and recycle, are less environmentally friendly

very likely when the infrastructure for these actions is not than reusing the same bag repeatedly. In turn, much less

in place or when doing so introduces barriers that are material is used to create a reusable shopping bag than to

otherwise not present in people’s lives when driving to create paper and plastic shopping bags. Education also is

work in the usual way. The many influences and factors important because the public sees global warming as a

involved provide an advantage; they open the prospect of problem but gives it a low priority in relation to other issues

multiple places to intervene, an absolute essential for (e.g., education, health care). Global climate change ap-

wicked problems. The multiple influences also convey that pears to be less of a concern because it is not clearly local

a multidisciplinary perspective is critical in the design of or local enough (Leiserowitz, 2005; Uzzell, 2000; Weber,

systems (e.g., urban planning, use of alternative energies), 2006). Education about the nature and scope of the prob-

social policy, and marketing, as are the essential contribu- lems and what will be required to address them thus re-

tions psychology can make to encourage changes in perti- mains essential.

nent affect, cognition, and behavior (Schmuck & Vlek, Message framing. Excellent work has demon-

2003; Steg, Dreijerink, & Abrahamse, 2006). strated the power of messages to encourage proenviron-

346 July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist

mental behaviors. I mentioned earlier the use of social when an appliance is turned on. The reviews referred to

norms as an example to foster the reuse of towels in hotels. above indicate that feedback saves (reduces) between 5%

Other research has shown that normative information in- and 15% of gas and electricity consumed and that the

fluences energy use in the home (Nolan, Schultz, Cialdini, effects are enduring. Feedback plus social reinforcement

Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2008). The influences seem to (e.g., for meeting or exceeding some criterion) or the lack

be out of consciousness; that is, people are unaware of the thereof (e.g., smiley vs. sad faces on utility bills) helps even

influence on their behavior and indeed even state explicitly, further. More efforts are underway to provide clear feed-

albeit incorrectly, that the normative information was not back (e.g., on the driver consoles of some hybrid cars) and

an influence. to connect momentary behavior (e.g., driving style at the

Messages surround us in everyday life (e.g., about moment) to energy use. The potential here is enormous,

littering, nutrition, seat-belt use). Most of these messages, and largely untapped, despite strong demonstrations about

however, do not rely on what we have learned about palpable impact.

message framing. Indeed, some of the messages present Decision making. Decision making and social

information (e.g., “Many people litter, please do not be one cognition more generally are pertinent in fostering envi-

of them.”) that is likely to exacerbate the problem by ronmentally sustainable behaviors (e.g., Nickerson, 2007).

normative modeling of the behavior opposite from the one All sorts of decisions (e.g., purchasing appliances, renovat-

that is needed (e.g., Cialdini, 2003). There is enormous ing one’s home, selecting an automobile) involve choices

untapped potential here to foster efficient use of energy and and trade-offs. Many lines of work are relevant, but let me

proenvironmental activities. In many cases, the need is not illustrate the area by mentioning choice architecture, that is,

to add to messages that are coming at us daily but rather to how choice is structured (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

integrate our science so the messages have an impact on Choice is always presented in some way that is not

what they are designed to accomplish. truly neutral (e.g., always within the context in which it is

Worth mentioning, but yet to be exploited, are priming presented and whether a default option refers to one way of

interventions, that is, the presentation of stimuli in the acting versus another). For example, when people are asked

environment that activate and increase the probability of whether they wish to enroll in a company retirement plan,

behavior (Bargh & Morsella, 2008). Elegant research has often the default position (not enrolling) means that most

shown that the presentation of stimuli and cues that are not do not enroll. Enrollment, even despite the added incentive

perceived consciously can influence subsequent behavior. of receiving matching (free) money from an employer, is

Incidental objects that are made visible (e.g., brief cases) or infrequent even though, when explicitly asked, people say

smells (e.g., all purpose cleaner) can influence performance they want a plan. There is a strong tendency to opt for the

(e.g., competitiveness and being neater, respectively; see status quo or default position, which is captured nicely by

Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). What one perceives indirectly the statement that one should never underestimate “the

can activate subsequent reactions and behaviors. The acti- power of inertia” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008, p. 8). If the

vation refers to the increase in the probability of action. As default position is reversed, that is, if doing nothing leads

with social norms, the influence often is not recognized, to enrollment or if one has to choose explicitly (and there

identified, or acknowledged by those exposed to the cues is no default position), then enrollment is much higher.

(see Bargh, Gollwitzer, Lee-Chai, Barndollar, & Troet- Programs in retirement enrollment and organ donations are

schel, 2001). concrete demonstrations of the importance of choice archi-

Feedback or knowledge of results. Much tecture and show that seemingly insignificant details of

of the information presented to us is not in a form that is choice presentation can very much influence how people

very useful because the metric is unfamiliar (e.g., a kilo- behave.

watt of energy use), the feedback is delayed (e.g., state- Default choices are already used in marketing. For

ments arrive at the end of the month after energy-consum- example, in magazine sales, the free issue of the magazine

ing behavior is long completed), and the feedback is not is followed by the default position of continuing to receive

connected readily to concrete behavior in real time (e.g., the magazine for a fee. The number of people who sub-

changing the temperature for heating or air conditioning) or scribe increases, as people pay rather than cancel. Default

real costs. There is now a fairly extensive literature explor- choices could be used to govern many energy-saving de-

ing many different ways of providing feedback about con- vices. As a common example, automated lighting—in

serving energy in the home (e.g., Darby, 2006; Fischer, which the light in each room goes off automatically (de-

2007; Nickerson, 2003). Feedback has been combined with fault position) unless activity is detected in the room—

different payment plans (direct payment from a keyboard in could be required in all new homes. Similarly, choice

the home) and diverse display systems (color feedback, structure could be used with economic incentives; a default

energy actually being used). Payment for energy in ad- nominal charge for a paper or plastic bag for one’s grocer-

vance (e.g., by credit card) rather than the usual way (after ies could encourage people to bring bags that could be used

use), daily feedback on how much has been spent as and reused or to carry one- or two-item purchases without

measured by a monitor or meter inside the home, and a bag. There is more to decision making than structuring

scores of variations on these practices have led to reduc- choice, but much of what we know about choice indicates

tions in energy consumption in several countries in which that making proenvironmental actions the default could

they have been tried. In some systems one can see the cost help.

July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist 347

Use of the media. The media (e.g., radio, TV, one energy-saving challenge to obtain over 100 miles per

Internet) are almost unlimited in their reach and potential. gallon in driving a hybrid car also included an economic

As a stellar illustration, for many years a field called incentive ($1 million in prize money; see http://hybridfest

entertainment education has been used to exert social .com/MPG.htm, http://mpgchallenge.greatrace.com/).

change on critical issues including family planning, adult Disincentives occasionally are used to turn people

literacy, HIV/AIDS prevention, sexual abstinence for ado- from their usual practices to alternative behaviors that

lescents, parenting, and preservation of the environment foster a sustainable environment. We are readily familiar

(Singhal, Cody, Rogers, & Sabido, 2003; Singhal & Rog- with high prices for gasoline and the decrease in driving

ers, 1999). The model in this approach has been to study (and use of fossil fuel) that they cause. Public reaction and

individuals within a given culture (e.g., surveys, focus protestation also can be a disincentive for practices un-

groups) and develop characters for an extended radio or friendly to the environment. One such protest was mounted

television drama series (depending on the medium avail- against a fast-food chain to get it to cease using food

able to the community) that reflect people and their daily containers made of polystyrene (brand name of Styro-

lives within the culture. The characters take on different foam), which is not only less biodegradable than alterna-

roles, deal with daily challenges of life within the culture, tives (paper) but generates chemical products in production

and model social-change behaviors. that contribute to pollution and produce greenhouse gases.

The goal is to achieve concrete social change at the Mobilization of grassroots groups extended to organized

level of the individual, the community, and society. For boycotts and pickets, moved the issue to national attention,

example, one of the early applications in Mexico focused and was eventually effective in getting the chain to change

on family planning and efforts to reduce fertility rates (see its product containers (see Gardner & Stern, 2002). Public

Sabido, 1981; Singhal & Rogers, 1999). Family life, mar- reaction to a product or practice (e.g., endorsement or outcry)

ital relations, and the daily drama and stressors were con- can be mobilized to provide incentives and disincentives that

veyed in detail as the televised drama series unfolded. The are critical because of their impact on goodwill and profits.

fictional family gained control over their lives and bene- Incentives often derive from marketing, economic,

fited from family planning—all in realistic episodes. The and policy considerations, which are valuable perspectives

impact: sales of contraceptives in the community rose to be sure and already offer supportive evidence on such

dramatically, and over a 5-year period, there was a 34% topics as energy use in the home. However, an economics

drop in birthrates. Similar effects were obtained in Kenya. perspective on the scheduling of rewards and how they are

More generally, the model has been used throughout the deployed is somewhat different from a psychological per-

world on other social issues. The model has produced spective. Actually, this is not a matter of perspectives

enormously engaging shows with high ratings; viewers or alone. Advances in understanding how reinforcers operate,

listeners become involved with the characters, and there is identifying which reinforcers control behavior (functional

a genuine impact on the targeted social behavior rather than analysis), and using antecedents of behavior to augment the

a mere “raising of awareness.” impact of rewards (establishing operations) from psycho-

We know the media can promote antisocial messages logical research (behavior analysis) could readily comple-

and behaviors (e.g., violence and crime in movies and videog- ment the use of incentives that emanate from economics. In

ames) and promote products (e.g., product placement). The a related vein, challenges and the addition of gentle forms

media are platforms for placement of messages that could of competition among neighborhoods, universities, com-

readily enhance health (e.g., no smoking, drug use, or unpro- munities, businesses, and cities to be more green, followed

tected sex among characters) and proenvironmental actions by recognition of the results, would be in keeping with

(e.g., routinely turning off lights). Admittedly, buying energy- what psychologists know about fostering behavior. Ad-

efficient appliances and having solar panels installed on one’s vances in understanding how efforts to control can backfire

roof will not easily fit into the narratives of most serial dramas, as, for example, in reactance (social psychological re-

but there are many other places to intervene in our favorite search) are quite pertinent as well. In short, we could

movies and television shows. mobilize incentives and disincentives better and more sys-

Incentives and disincentives. These obvi- tematically on the basis of psychological research already

ously can play a critical role at many levels (e.g., individ- available.

uals, groups, communities, and corporations). For fostering Social marketing. Marketing strategies have

sustainable actions, we are familiar with rebates and tax been used to promote sustainable behaviors. The approach

incentives for purchasing hybrid cars, solar panels in the is referred to as community-based social marketing

home, and energy-efficient light bulbs. Incentives have also (McKenzie-Mohr & Smith, 1999; see www.cbsm.com).

been used to foster sustainable farming, to reduce defores- Key elements include a thorough analysis of the behavior

tation, and to reverse the collapse of fisheries (Clayton, (goal) and marketing (advertising) with the goal of making

2009; Costello, Gaines, & Lynham, 2008). the desired sustainable behavior easier, more obvious, and

Incentives are not always economic. In many areas of more convenient than alternative behaviors. The steps in-

public life, “challenges” are provided, sometimes with a clude identifying barriers to (real and perceived) and ben-

financial incentive. A challenge not only encourages exten- efits of an activity, developing a strategy for change, testing

sive efforts to meet the challenge but also gives great visibility the strategy on a pilot basis, and evaluating impact. At

to the goal among those who do not participate. For example, www.toolsofchange.com, several examples of community-

348 July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist

based programs are provided that illustrate the approach place environmental concerns in broader contexts (see

and its effects in decreasing energy use at home and use of http://environment.harvard.edu/religion). The goal of the

pesticides and increasing use of public transportation, fuel- forum is to foster interaction and dialogue among those in

efficient driving among young drivers, bicycles as a pri- religion, science, ethics, public policy, and education.

mary means of transportation, telecommuting, behaviors Among the many educational highlights one can find at

that improve air quality, and recycling. The website pro- the forum’s website are position statements and views from

vides steps, costs, and outcomes (e.g., in emissions, in many religions on the relation and responsibilities of humans

energy saved) and thus shows how behavior change trans- to the environment, including worldviews, issues of steward-

lates to critical environmental outcomes (e.g., energy saved). ship, ethics, and practices that foster a sustainable environ-

Social marketing provides a broadly applicable ap- ment. The impact of this work is not found only in broad

proach. Barriers may be localized as a function of constraints position statements. Religious leaders are drawing on envi-

of the setting, the range of options that are feasible for a given ronmental concerns as part of their work with their congre-

behavior, and perceptions that might be moderated by culture, gations, and concrete actions that go beyond general ethical

ethnicity, age, and other variables of the target group. Behav- principles are being fostered and encouraged (e.g., Motavalli,

iors occur in contexts, and social marketing reflects an inte- 2002). Within psychology, religion and spirituality could con-

grative and systematic approach to addressing these contexts

tribute greatly to understanding and fostering sustainable be-

and increasing the likelihood of behavior change.

haviors. Understanding the roles of belief, commitment, and

Integrating and understanding multiple

broad views of the world and how these translate into action

influences. Research grounded in psychological theory

has integrated multiple influences to optimize change in fos- falls squarely within the realm of psychology.

tering environmentally sustainable behaviors (e.g., Hunecke, Use of special contexts and settings. Var-

Blöbaum, Matthies, & Höger, 2001). This is well illustrated ious contexts and settings provide special opportunities to

by the value-belief-norm theory (Gardner & Stern, 2002; foster sustainable behaviors. Businesses, schools, universi-

Stern, 2000b), a theory closely tied to data. Briefly, the theory ties, professional organizations, and local communities that

classifies different types of environmentally significant behav- have captive groups and contexts allow for focused inter-

iors and provides an account and a causal chain that elaborates ventions. An ethos and set of practices can be established

the role of values (e.g., altruism, egoism), beliefs (e.g., con- that foster sustainable behaviors. In business, for example,

sequences, perceived ability to make a difference), personal environmentally friendly work practices such as permitting

norms (e.g., sense of obligation), and behaviors (e.g., individ- work at home or providing incentives for using mass trans-

ual activities, participation in organizations). portation can be applied and fostered.

Whether an individual is likely to engage in proenvi- Settings and contexts raise opportunities to implement

ronmental behaviors may depend on (be moderated by) interventions that are unique to those settings. For example,

diverse variables (e.g., attitudes, personal capabilities, con- zoos and aquariums represent a unique opportunity for fos-

textual influences, and routines) and the type of behavior. tering environmentally sustainable behaviors (see World As-

For example, selection of a hybrid vehicle may be greatly sociation of Zoos and Aquariums, 2005). Surveys indicate that

influenced by one’s attitude toward the environmental im- zoos are a credible and trustworthy source of information.

pact of the car (e.g., energy use, consumption) and toward Moreover, people welcome information from zoos regarding

luxury (e.g., speed, power, size of the car) and by personal the environment and climate change, and they see conserva-

capabilities (e.g., social status, financial resources). The tion advocacy as part of the mission of zoos (Wadler, 2007).

theory conveys why just targeting behavior free from other Also, parents see zoos as contributing to children’s moral

considerations is likely to have minimal impact. Multiple development and as providing an opportunity to teach respect

moderators and mediators have been identified that can be for nonhuman animals and nature. These findings alert us to

used to optimize the impact of interventions. There are opportunities for interventions (e.g., demonstrations, exhibits)

other integrative models that bring together multiple influ- that can focus on the dependence of nonhuman animals on

ences such as resource availability, governmental influ- contextual influences that humans can control (e.g., protecting

ences, technological influences, and the varied goals of habitats and ecosystems) and, indeed, on how our own less

decision makers (e.g., Gifford, 2008). Such models lend than altruistic interests are served by care for all animal and

themselves to empirical evaluation to test links among the plant life. Then there is of course the higher moral imperative

influences and how these can translate to action.

of the “reverence for life” of which this care is a part (Meyer

Religion and ethics. Religion and ecology have

& Bergel, 2002; Schweitzer, 1923/1949).10

been part of the discourse on fostering a sustainable envi-

Diverse contexts and settings raise special opportuni-

ronment for decades (see Tucker & Grim, 2001). Among

the challenges are reorienting people to convey the stands ties for localizing and setting-specific interventions. Within

of diverse religions on responsibility and respect in relation some settings (e.g., business, universities, grocery stores) it

to the environment and utilizing religion to “awaken a is possible to evaluate the impact of actions that affect

renewed sense of awe and reverence for the Earth”

(Tucker, 2002, p. 14). A forum on religion and ecology that 10

Albert Schweitzer (1875–1965) was a physician, philosopher, and

is the largest international multireligious project of its kind theologian whose philosophy of “reverence for life” served as the basis for

encompasses conferences, publications, and resources that his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952.

July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist 349

conservation and energy use (e.g., specific practices that ing this issue to light and providing emphasis? I thought

actually reduce energy consumption). In other settings you would never ask.

(e.g., zoos, aquariums, museums of natural history), the

focus may be more on views and attitudes. These latter foci Why Raise the Topic Now?

may translate to behavior change and actions that make a

difference. It might be that a broad alignment of messages Urgency and Scope of the Problems

and cues in many contexts and settings will sensitize people Actually, several influences can be identified that are new,

to other interventions or summate in a way that exerts newly salient, or at a critical stage. First and foremost is

direct impact. urgency. The need for action in response to climate change

General comments. I have sampled several is more evident than ever before. Whether the issue is

psychosocial interventions. Effective interventions in many endangered species, coastlines, or water and food supplies,

instances will need to take into account local conditions, current levels and trends indicate that action is needed

culture, context, and other factors. A highlight of many of (L. B. Brown, 2008; Speth, 2005). Invariably, trends are

the interventions is that they represent platforms or tem- based on linear extrapolations and slippery-slope types of

plates that can be adapted to different local conditions. For worries that often do not materialize. We are well beyond

example, social marketing, entertainment education, and extrapolations. For example, we do not need to look at

interventions based on value-belief-norm theory provide a “trends” for glaciers melting; the changes are stark already

structure that adapts to diverse groups, conditions, and (British Antarctic Survey, 2008; Gillett et al., 2008; John-

contexts. This platform feature is important to allow adap-

son, Bentley, & Gohl, 2008). Similarly, global warming is

tation of effective interventions to many cultures and coun-

increasing the mortality rates of trees, a process mediated

tries.

by pathogens, insects, and droughts (van Mantgem & Ste-

The diversity of psychology’s content areas maps well

phenson, 2007). Here, too, this is not something coming;

onto the challenge of and the scope of strategies needed for

these effects are here. Some of the problems that contribute

fostering behaviors that sustain the environment. There is

to the urgency are not merely getting worse in a linear

general agreement that multiple interventions are needed

fashion. For example, overpopulation is exponential, and a

and that they are needed at multiple levels (e.g., Gardner &

Stern, 2002; Maibach, Roser-Renouf, & Leiserowitz, seemingly small annual growth rate of 1.4% in the world

2008). Intervening in many contexts and drawing on the population means that it will actually double in approxi-

diversity of our strengths could make a difference. mately 50 years (Gardner & Stern, 2002). The use of

The idea of fostering sustainable behavior through energy and resources to accommodate this increase alone

psychological science is not new. The oil shortage and will accelerate the problems of climate change.

national energy crisis of the 1970s first brought attention to Second, breakthroughs in assessment methods and

the impact of the use of fossil fuels on the environment as novel statistical models that examine multiple systems

well as to many issues that now face us again (e.g., Na- mean that we can recognize and better document individual

tional Research Council, 1979). In 1973, the first multidi- problems (from Table 2) and their interrelations (see, e.g.,

mensional scale to measure environmental concern was Diaz & Rosenberg, 2008; Rosenzweig et al., 2008). We

developed with the goal of facilitating psychological re- know that global warming, decreased food availability in

search (Maloney & Ward, 1973). The measure included several countries, loss of fisheries, increasing population,

components (verbal commitment, actual commitment deforestation, increased oxygen depletion in oceans, lakes,

[what a person does], affect, and knowledge) that still and rivers, and other such individual wicked problems are

figure prominently in current theories and applications all intricately related. For example, some animal and plant

(Matthies & Blöbaum, 2007). Since that time, psycholog- species are moving to additional or different locations in

ical theory, research, and application in this area have response to key environmental changes (e.g., Lenoir, Gé-

flourished, as reviewed in many books (e.g., Bamberg & gout, Marquet, de Ruffray, & Brisse, 2008). Several spe-

Moser, 2007; Gardner & Stern, 2002; Nickerson, 2003; cies that do not have this environment-enforced mobility

Schmuck & Schultz, 2002) and articles (e.g., Oskamp, are at risk for extinction (Vié, Hilton-Taylor, & Stuart,

1995, 2000; Stern, 1992). The different areas of psychol- 2008). We can now assess how problems cascade into

ogy relevant to fostering sustainable behaviors are illus- others and further exacerbate degradation of the environ-

trated by the number of different journals with series of ment. For example, and as noted previously, global warm-

articles on the topic. Examples in the English language ing can lead to the loss of trees—the same trees that help

include the American Psychologist (2000, Vol. 55, No. 5), reduce greenhouse gases and limit global warming. The

Human Ecology Review (2003, Vol. 10, No. 2), Journal of broad impact of a problem can be better monitored now,

Environmental Psychology (1995, Vol. 15, No. 3), Journal and such better monitoring often conveys a problem’s

of Humanistic Psychology (2001, Vol. 41, No. 2), and accelerated pace.

Journal of Social Issues (1995, Vol. 51, No. 44; 2000, Vol. Third, more of the public recognizes a problem. In the

56, No. 3; 2007, Vol. 63, No. 1). If the area has been so United States, 92% of the public are aware of global

well developed for a period exceeding three decades, why warming; 76% view climate change as a serious problem

mention all of this now? What is new that warrants bring- (Leiserowitz, 2006). Approximately one half of the U.S.

350 July–August 2009 ● American Psychologist

public believe climate change is already having a danger- human behavior (e.g., energy-efficient behaviors, adoption

ous impact on people or will within the next decade (see of technology) is natural for psychologists. There are op-

Maibach et al., 2008). Increased recognition of degradation portunities we should seize and others we should create.

of the environment and the need to foster change was Second, the public is involved in science and its use

enhanced by An Inconvenient Truth, the documentary and and application more than ever before, as reflected, for

book by Al Gore (2006), former vice president of the example, in the term citizen scientist and in organizations

United States. His contribution was recognized by many that foster the participation of amateur scientists (e.g.,

awards, including most prominently, the Nobel Peace Prize www.sas.org). More generally, businesses, foundations,

(2007). All of that attention has helped to make not-so-new science, mathematics, and medicine have turned over var-

concerns fresher and more salient to the public.11 ious challenges and incentives to the public at large and to

Fourth, what is new is that critical problems and their anyone interested. Some of these challenges have been

consequences are now felt on a global scale. Energy con- visible (e.g., privatization of space flight suitable for pas-

sumption (e.g., oil, ethanol) in one or a few industrialized sengers), and the public follows them in the news, but there

countries has cascading effects that spread to other coun- are hundreds of other less-visible challenges that have been

tries. These effects can be felt in the price of energy but addressed and solved in this way (e.g., identifying treat-