Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jbi 1062

Uploaded by

Dina afrisaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jbi 1062

Uploaded by

Dina afrisaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/227772108

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya's Maasai Mara: What future for

pastoralism and wildlife?

Article in Journal of Biogeography · June 2004

DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01062.x

CITATIONS READS

255 1,779

2 authors:

Richard Lamprey Robin Reid

8 PUBLICATIONS 327 CITATIONS

Colorado State University

118 PUBLICATIONS 7,842 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Wildlife aerial surveys in Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda View project

Sustainability Science View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Richard Lamprey on 12 January 2023.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2004) 31, 997–1032

ORIGINAL Expansion of human settlement in

ARTICLE

Kenya’s Maasai Mara: what future for

pastoralism and wildlife?

Richard H. Lamprey1* and Robin S. Reid2

1

Uganda Wildlife Authority, PO Box 3530, ABSTRACT

Kampala, Uganda and 2International

Aim Wildlife and pastoral peoples have lived side-by-side in the Mara ecosystem

Livestock Research Institute, PO Box 30709,

Nairobi, Kenya

of south-western Kenya for at least 2000 years. Recent changes in human

population and landuse are jeopardizing this co-existence. The aim of the study is

to determine the viability of pastoralism and wildlife conservation in Maasai

ranches around the Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR).

Location A study area of 2250 km2 was selected in the northern part of the

Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, encompassing group ranches adjoining the MMNR.

Emphasis is placed on Koyake Group Ranch, a rangeland area owned by Maasai

pastoralists, and one of Kenya’s major wildlife tourism areas.

Methods Maasai settlement patterns, vegetation, livestock numbers and wildlife

numbers were analysed over a 50-year period. Settlement distributions and

vegetation changes were determined from aerial photography and aerial surveys

of 1950, 1961, 1967, 1974, 1983 and 1999. Livestock and wildlife numbers were

determined from re-analysis of systematic reconnaissance flights conducted by

the Kenya Government from 1977 to 2000, and from ground counts in 2002.

Corroborating data on livestock numbers were obtained from aerial photography

of Maasai settlements in 2001. Trends in livestock were related to rainfall, and to

vegetation production as indicated by the seasonal Normalized Difference

Vegetation Index. With these data sets, per capita livestock holdings were

determined for the period 1980–2000, a period of fluctuating rainfall and primary

production.

Results For the first half of the twentieth century, the Mara was infested with

tsetse-flies, and the Maasai were confined to the Lemek Valley area to the north of

the MMNR. During the early 1960s, active tsetse-control measures by both

government and the Maasai led to the destruction of woodlands across the Mara

and the retreat of tsetse flies. The Maasai were then able to expand their settlement

area south towards MMNR. Meanwhile, wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) from

the increasing Serengeti population began to spill into the Mara rangelands each

dry season, leading to direct competition between livestock and wildlife. Group

ranches were established in the area in 1970 to formalize land tenure for the

Maasai. By the late 1980s, with rapid population growth, new settlement areas had

been established at Talek and other parts adjacent to the MMNR. Over the period

1983–99, the number of Maasai bomas in Koyake has increased at 6.4% per annum

(pa), and the human population at 4.4% pa. Over the same period, cattle numbers

on Koyake varied from 20,000 to 45,000 (average 25,000), in relation to total

rainfall received over the previous 2 years. The rangelands of the Mara cannot

*Correspondence: Richard H. Lamprey, Uganda support a greater cattle population under current pastoral practices.

Wildlife Authority, PO Box 3530, Kampala,

Uganda. Tel.: +256 77 704596. Conclusions With the rapid increase in human settlement in the Mara, and with

E-mail: lamprey@infocom.co.ug imminent land privatization, it is probable that wildlife populations on Koyake

ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd www.blackwellpublishing.com/jbi 997

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

will decline significantly in the next 3–5 years. Per capita livestock holdings on the

ranch have now fallen to three livestock units/reference adult, well below

minimum pastoral subsistence requirements. During the 1980s and 90s the

Maasai diversified their livelihoods to generate revenues from tourism, small-

scale agriculture and land-leases for mechanized cultivation. However, there is a

massive imbalance in tourism incomes in favour of a small elite. In 1999 the

membership of Koyake voted to subdivide the ranch into individual holdings. In

2003 the subdivision survey allocated plots of 60 ha average size to 1020 ranch

members. This land privatization may result in increased cultivation and fencing,

the exclusion of wildlife, and the decline of tourism as a revenue generator. This

unique pastoral/wildlife system will shortly be lost unless land holdings can be

managed to maintain the free movement of livestock and wildlife.

Keywords

Kenya, Maasai Mara, pastoralism, rangelands, bomas, livestock, wildlife.

wildlife (IIED, 1994; Western, 1994; Berger, 1996; Igoe &

INTRODUCTION

Brockington, 1999; Barrow et al., 2000; Metcalfe, 2000).

It has become a conservation dictum in Africa that the Another factor limiting the effectiveness of ICDPs, often entirely

survival of the continent’s wildlife, and particularly of its ignored by community conservation initiatives, is human

‘megafauna’, into the twenty-first century will depend on the population growth and privatization of land. In examining the

goodwill of local communities. It is argued that the support prospects of sustainable wildlife harvest on community land,

of communities for wildlife can be enhanced through Barrett & Arcese (1995, p. 1076) contend that ‘if human

community-based wildlife management (CBWM), a process populations grow past the point where a sustainable harvest can

in which local people participate in, and benefit from, the provide satisfactory benefits on a per capita basis, ICDPs should

conservation and management of wildlife on their land (Kiss, be expected to fail for the same reasons that local cooperation

1990; IIED, 1994; McNeely, 1995). Throughout Africa, may have been lacking prior to their initiation’.

integrated conservation and development projects (ICDPs) Since the 1980s, CBWM has been put forward as a new

have been established by donors and non-governmental paradigm of conservation thinking (Adams & Hulme, 2001).

organizations (NGOs) to encourage and promote CWBM, However, as long ago as the 1950s wildlife managers in Kenya

and the sustainable use of natural resources (Gibson & were making efforts to ensure that local people benefited from

Marks, 1995; IIED, 2000; Barrow & Murphree, 2001). wildlife, using approaches that many conservationists today

Wildlife-based ICDPs cover a range of interventions, from still regard as innovative. For example in 1951, the Kenya

the development of local craft markets near wildlife tourism Game Department initiated a scheme by which sport hunters

areas, to the full ownership of wildlife and the sharing of in ‘controlled areas’ paid a game fee for each animal shot to the

benefits from tourism or sport hunting (Ashley & Roe, 1998; local district council (Game Department Annual Report,

Hulme & Murphree, 2001). 1952). The scheme ran for 26 years1 and generated revenues

The CBWM approach has now become enshrined in national equal to those from game-viewing tourism (Strickland, 1973;

wildlife policies in eastern Africa (KWS, 1990; Wildlife Division, Casebeer, 1975; R.H. Lamprey, unpubl. data). A second

1998; TANAPA 1994; UWA, 2002), where particular attention approach, proposed by the Game Policy Committee of 1956,

has been focussed on conserving wildlife on land owned by and implemented in 1961 prior to independence, was to

pastoralists such as the Maasai (Western, 1984; Homewood & transfer game reserves to local government councils. District

Rodgers, 1991; Igoe & Brockington, 1999). It is asserted that in councils, in their control of ‘Trust land’, were encouraged to

the pastoral savannas, wildlife has coexisted with man and his adopt game reserves as ‘African District Council Game

stock for millenia (Parkipuny, 1997), and that there is little Reserves’, where ‘human affairs are regulated by… council

competition between the two. Therefore CBWM initiatives in by-laws and faunal matters by the Wild Animal Protection

savannas, with benefits to communities through game-viewing Order (the legislation of the Game Department)’ (Game

tourism or sport hunting, will have a higher chance of success Department Annual Report, 1962, p. 4). After independence,

than in agro-pastoral or agricultural areas where wildlife and

people may be mutually exclusive. Critical factors limiting the 1

For a short period, from 1952 to 1958, hunting was prohibited

development of CBWM in pastoral areas include insecurity of during the independence struggle (referred to by the colonial gov-

land tenure, inequitable distribution of benefits within com- ernment as the ‘emergency’). Sport hunting was banned in Kenya in

munities, outdated legislation and lack of expertise in managing 1977.

998 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

these reserves were designated ‘county council reserves’2 and successfully manage and derive benefits from wildlife on their

legally gazetted, the principal areas being Maasai Mara, rangelands. Maasai District Councils were managing their game

Amboseli and Samburu. District councils3 received substantial reserves, and earning revenues that could, in theory, be put

grants from Government in the early 1960s to develop these towards improving public services for their electorate. On

areas for tourism, and to collect revenues from entry fees, rangelands adjacent to the reserves, groups of Maasai had land

camping sites and lodge concessions. Maasai Mara and tenure and were in a position to directly benefit from tourism.

Samburu have become prime tourism areas in Kenya A critical test area for the success of wildlife conservation on

(Douglas-Hamilton et al., 1989; Lamprey, in prep.).4 community land is the Maasai Mara ecosystem in south-

Meanwhile, beginning in the mid-1960s, the issue of land western Kenya. The area has a long history of pastoral–wildlife

tenure on Maasai rangelands was being addressed by the interactions as indicated by the detailed palaeontological

establishment of ‘group ranches’. As part of Kenya Govern- research of Marshall (1990). As early as 2000 years ago, in

ment’s land adjudication programme, groups of Maasai were the Neolithic period, the Mara was occupied by advanced

given title deeds to tracts of grazing land which they had pastoralists, who managed their cattle, sheep and goat herds

traditionally used over a long period (Lawrance Report, 1966). for maximized production and who did not hunt wildlife.

There were three closely linked objectives to the group ranch Today, the Mara supports an exceptionally large and diverse

programme (Lewis, 1965; Davis, 1970; Hedlund, 1971; Oxby, population of savanna wildlife (Lamprey, 1984; Broten & Said,

1982; Rutten, 1992). First, it was anticipated that meat produc- 1995; Ottichilo, 2000), and in the wildlife dispersal area around

tion in rangeland areas would be increased, in line with national the core Maasai Mara National Reserve (MMNR), Maasai

livestock development policies. Secondly, it was felt that if the pastoralists have group or individual land tenure. Tourism in

Maasai were given their own land they would manage it in an the MMNR, and in adjacent Maasai ranches, has increased 10-

ecologically sound way by designing their own grazing manage- fold since the mid-1980s, with many millions of dollars being

ment schemes, selling surplus stock, and controlling livestock generated for local government councils and for the Kenya

diseases effectively. Thirdly, by settling people permanently on economy in general (Douglas-Hamilton et al., 1989; Lamprey,

their own land, the state could more easily meet their needs for in prep.). CBWM is considered to be highly successful in the

basic health care and education. The concept of group mem- Mara, with direct involvement of the Maasai and local

bership was enshrined in the Land (Group Representatives) Act, government in wildlife conservation and in the generation of

1968, which stated that ‘each member shall be deemed to share in revenue from tourism (Talbot & Olindo, 1990).

the ownership of the group ranch in undivided shares.’ Whilst However, hopes for integrating pastoralism with conserva-

the ranch is owned by a group of ‘members’ acting as a corporate tion in the Mara are fading. Over the last 20 years, large tracts of

body, the livestock remain the property of individual members. grazing land on the Loita plains in the north-east of the

By organizing themselves into groups, adopting constitutions, ecosystem, used seasonally by livestock and wildlife, have been

and electing group committees, the members could acquire leased out by Maasai for commercial wheat cultivation. Due to

loans from the Agricultural Finance Corporation for the habitat loss, poaching and other disturbances, resident wildlife

development of their land, for such projects as the construction populations in the Mara have declined by over 70% over the last

of dips, dispensaries and schools. 20 years (Ottichilo, 2000; Homewood et al., 2001; Serneels &

It was also recognized that group ranches could earn Lambin, 2001). Meanwhile, in group-owned ranches adjacent

revenues from tourism. In certain areas, such as in Narok to the MMNR, the human population is increasing very rapidly

District, the potential for tourism was seen as being so high that (Lamprey, 1984; Reid et al., 2003). As pressure builds for land,

ranch planners in the 1970s were concerned that ‘because of ranch members are diversifying their livelihoods through

such a lucrative source of funds (from tourism), these ranches cultivation and income-generation from tourism, but there is

have not yet had to apply for a development loan. This worries a dire inequality in earnings between the ranch leadership and

the Ranch Planning Office in the District because… without a ordinary members (Homewood et al., 2001). During recent

loan to repay, there will be no significant offtake of cattle, but planning meetings for the Mara, many Maasai indicated that

rather, ranch finances will be used to purchase more cattle after ranch subdivision, they would prefer to cultivate (ACC,

thereby leading to a chronic overstocking problem’ (Doherty, 2001). If this were to occur on a large scale, it is inevitable that

1979, p. 7). These concerns aside, by the 1970s many of the fences will be erected, and wildlife movements will be disrupted;

critical elements were in place to ensure that the Maasai could cultivation and large herds of wildlife are incompatible.

Subdivided ranches in the Mara ecosystem that receive

sufficient rainfall for agriculture, such as Lemek GR, now have

2

Initially established in the late 1940s as ‘national reserves’ under large areas under cultivation (Thompson, 2002). In his

Kenya Royal National Parks, these county-council ‘game reserves’ were economic analysis of landuse on the Mara plains, Norton-

again redesignated as ‘national reserves’ under the 1976 Wildlife Griffiths (1995) argues that the Maasai forgo opportunities for

(Conservation and Management) Act. However, they continued to be more profitable forms of landuse such as cultivation, and

managed by local councils.

should now be compensated to maintain their land for wildlife.

3

In Kenya, districts are managed by ‘county councils’. A recent body of research presented by Homewood et al.

4

Amboseli was designated a National Park in 1974. (2001) presents a more optimistic scenario for the Mara, in

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 999

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

Figure 1 The study area (boxed) in the

Serengeti Mara ecosystem. The dashed line

indicates the limit of the seasonal movements

of migratory wildebeest. SNP, Serengeti

National Park; MMNR, Maasai Mara

National Reserve; NCA, Ngorongoro

Conservation Area; MGR, Maswa Game

Reserve; IGR, Ikorongo Game Reserve;

GMR, Grumeti Game Reserve.

which the Maasai have a choice of landuse options. They assert aerial photographs taken over the period 1950–74, and from

that the Maasai remain relatively wealthy in terms of cattle ground and aerial surveys in 1983 and 1999. Livestock and

ownership, and that sustainable pastoralism can be balanced wildlife populations were determined by aerial censuses

with other ‘conservation-compatible’ livelihoods to absorb (‘systematic reconnaissance flights’, SRFs) conducted by the

future population growth. They maintain (Homewood et al., Kenya Government over the last 20 years. Livestock units per

2001, p. 12547) that ‘the size of the livestock population is linked capita were calculated to assess whether pastoralism can

to pastoralists decisions and their wealth… A possible tradeoff remain the principal livelihood for Maasai in the Mara

exists for pastoralists between increasing livestock holdings and ranches. The consequences of these findings are discussed in

maintaining tourist-related incomes through wildlife conserva- the context of other livelihood options, and of the imminent

tion. Similar tradeoffs have to be made by pastoralists concern- fragmentation of group ranches into individual holdings.

ing the leasing of their land for mechanized agriculture and the

expansion of small-scale cultivation.’ The study concludes (p.

THE STUDY AREA

12549) that ‘the (Mara) ecosystem could accommodate future

population growth at low ecological cost provided land zoning The study area of 2250 km2 lies in the far north of the

manages settlement, subsistence agriculture and their access to Serengeti-Mara ecosystem (SME)5 (see Fig. 1), and includes

and impact on key resources (swamps, water holes, wildlife the northern part of the MMNR, the adjacent Maasai ranch of

migration routes).’ The study also recognizes the urgent need Koyake (‘Koyake Dagurugurueti’) (971 km2) and parts of

for a more equitable distribution of tourism revenues between Lemek, Ol Chorro Oirowa (‘Olchoro Oiroua’) and Ol Kinyie

the elite and ordinary ranch members. Group Ranches. Place names for the study area are shown in

Our paper describes changes in human, livestock and Fig. 2. The area is bordered in the north by the Mara River and

wildlife populations in the Mara over the last 50 years, to re-

assess whether pastoralism can remain a viable livelihood

5

option for the Maasai, and whether wildlife conservation has a The Serengeti-Mara ecosystem encompasses the seasonal movements

of the migratory wildebeest (Gwynne & Croze, 1975; Pennycuick, 1975;

future on the group ranches. In a selected study area Sinclair, 1979), and includes the Serengeti National Park and Maswa,

encompassing key Maasai ‘group ranches’, temporal changes Grumeti and Ikorongo Game Reserves in Tanzania, and the Maasai

in settlement distribution were determined from an analysis of Mara National Reserve and adjacent rangeland areas in Kenya.

1000 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

Figure 2 The study area in the Mara

(square), and location of Maasai Mara

National Reserve, group ranches (GRs) and

names referred to in the text.

the land unit of the agricultural Kipsigis people (elevation July–October period being the ‘dry-season.’ The climate and

> 2100 m), in the east by the Loita plains (1800 m), in the vegetation of the study area are characteristic of eco-climatic

west by the steep Siria escarpment in Trans-Mara (2000 m), zone IV, the ‘semi-arid to subhumid zone’ defined by Pratt &

and in the south by the MMNR (1700 m). Gwynne (1977) and Sombroek et al. (1980).

The Mara study area receives 600 mm of rainfall in eastern The soils in the Mara are ‘phonolitic tuffs’ derived from

areas, rising to 1000 mm at the western side where climate is volcanic ash (Glover, 1966), and havemoderate-high fertility

strongly influenced by the Lake Victoria weather system (Jaetzold & Schmidt, 1983). These blanket a geological

(Glover, 1966; Norton-Griffiths et al., 1975; Ministry of basement composed of Miocene quartzites, gneisses and

Agriculture, 1977; Epp & Agatsiva, 1980; Ottichilo, 2000). schists (Williams, 1964; Wright, 1967). The exposure of the

The seasonal north–south shift of the inter-tropical conver- basement is represented in the stony hills in the Lemek and

gence zone brings the ‘short rains’ in October–November Siana areas, and in the west by the prominent Siria escarpment,

and the ‘long rains’ in March–May (Brown & Cocheme, 1973). a major fault line in the basement (Saggerson, 1972). The Mara

Soil moisture is generally sufficient to maintain a single river, the most prominent river of the region, flows southwards

growing season from November–June (Lamprey, 1984)6 the along the base of the escarpment. Numerous streams and

watercourses drain the central plains into the Mara River, the

6

largest being the Talek and its tributaries the Olare Orok,

Calculated using the potential evapo-transpiration (PET) data of

Ntiakitiak (‘Jagartiek’), Kaimurunya and Ol Sabukiai

Woodhead (1968) modified according to Brown & Cocheme (1973),

and on the basis that the ‘growing season’ begins when rainfall exceeds (Lamprey, 1984; Reid et al., 2003). Aside from these perennial

PET/2 (FAO, 1978). watercourses, the most important sources of permanent

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1001

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

freshwater are springs arising from the hills in the Lemek/ with mud and dung daub, are located within the boma to left

Aitong area. and right of the gate. The huts (Maa sing: enkaji), which may

The vegetation of the study area comprises tall and short be considered as ‘sub-households’ (Thompson, 2002), are built

grass plains dominated by Themeda triandra and Pennisetum and maintained by the husband’s wives (Lamprey, 1984;

spp., interspersed by a patchwork of Acacia woodlands and Homewood & Rodgers, 1991; Coast, 2000). Each night the

bushlands, thicket and riverine forest (Lewis, 1934; Betts, households bring their livestock through their respective gates

1953; Darling, 1960; Heady, 1960; Trapnell et al., 1969; into central compartments of the boma, to protect them from

Trump, 1972; Taiti, 1973; Herlocker, 1976; Epp & Agatsiva, predators and stock rustlers. The pattern of the ‘traditional’

1980; Lamprey, 1984). During the 1960s previously wooded il-Purko Maasai boma, still common in the remote areas of

areas were radically transformed into grassland by the Narok District, is shown in Fig. 3.

actions of fire and elephants (Lamprey, 1984; Dublin, The typical il-Purko boma in the Mara is occupied for

1995). Hillslopes in the north remain colonized by extensive 4–5 years (Lamprey, 1984), after which the settlement

tracts of Tarchonanthus camphoratus (Maa: ol-leleshwa) becomes uninhabitable due to the build-up of dung and

bushland, impalatable to stock (Ivens, 1967; Pratt & parasites. Before evacuation, a new boma is constructed

Gwynne, 1977). nearby, in which some of the more durable building

materials of the old boma are reused. As soon as the old

boma has dried out, it is burned.10 Unlike transhumant

MAASAI SETTLEMENTS AND LAND TENURE

Maasai such as the il-Kisongo of Amboseli, who have wet

The Maasai are pastoral people of Nilotic origin who moved and dry-season bomas (Western, 1973), the il-Purko Maasai

southwards into Kenya’s central rangelands in the seven- of the Mara construct permanent bomas that are used year-

teenth century7 (Berntsen, 1979; Waller, 1979; Ehret, 1984). round, with little transhumance (Lamprey, 1984; Coast, 2000;

The Kenya Maasai are traditionally divided into 11 sections Thompson, 2002). Some small-scale maize cultivation may

(Maa: iloshon) occupying specific areas, and defined by be practised immediately around bomas, but this is not

differences in dialect, culture and ceremonial procedures. generally a feature of ranch areas close to MMNR, due to the

The Mara study area falls within the land unit of the il- risks of crop-raiding by wildlife.11 When grazing areas far

Purko section of the Maasai, who, since their relocation from the bomas are used, the Maasai herders construct

from Laikipia by the colonial authorities in 1913 (Sandford, temporary livestock camps (Maa pl.: ormwati) as bases to

1919; Lamprey & Waller, 1990), occupy northern and contain stock at night. These simply comprise a circular

central Narok District. fence and internal stock compartments, made from Acacia

In common with other sections, the traditional il-Purko bushes cut locally. Livestock camps are generally abandoned

Maasai homestead or boma8 (Maa sing.: enkang), comprises a after a single season, and the fence is soon destroyed by

ring of low huts surrounding a central livestock coral termites or grass fires.

(Lamprey, 1984; Thompson, 2002). One or more families or In the Mara, as elsewhere in Maasailand, bomas are

‘households’ (Maa pl: olmarei) form a semi-permanent core generally clustered in favoured localities (Maa pl: in-kutot),

group within this residential association, often bound together where soil and drainage conditions are suitable (Western &

by age-set and clan relationships (Thompson, 2002). Each Dunne, 1979). As these ‘neighborhoods’ expand, trading

household head, usually a married man, ‘owns’ a gate in the centres, schools, dispensaries and cattle dips are established,

boma fence.9 The huts, consisting of a frame of poles covered and eventually these areas may become small townships.

Group ranches were established in the Mara in 1970. In the

northern plains, Koyake Dagurugurueti, Ol Kinyie and Lemek

7

The reader is referred to Hollis (1905); Sandford (1919); Fosbrooke Group Ranches were registered as ranches with group title,

(1948); Jacobs (1965) and Spear & Waller (1993) for a general de- whilst Ol Chorro Oirowa was registered as a private ranch (see

scription of the Maasai and their social structure, and to Berntsen Fig. 2). As described later in this report, the Mara ranches are

(1979); Waller (1979) and Ehret (1986) for analyses of the Maasai

‘migrations’ and resettlements. Nestel (1984), Bekure et al. (1991);

now being subdivided into private land plots. Currently, the

Homewood & Rodgers (1991) and Rutten (1992) describe the nutri- main physical signs of this process are the fragmentation of

tion, economics and ecology of Maasai pastoralism. bomas into family units (see Fig. 4), and the placing of

8

Bomas are often erroneously referred to as ‘manyattas’. ‘Manyatta’ is boundary markers around land holdings.

the Maasai word for the (generally unfenced) settlements of the war-

riors (Maa pl.: il-murrani), but has reached common usage to refer to

10

any Maasai settlements with permanent or semi-permanent huts. A boma may also be abandoned if an important occupant dies.

Jacobs (1965) prefers the terms ‘kraal camp’ for permanent or semi- 11

Further from the MMNR both small-scale and large-scale cultiva-

permanent settlements. We use the term ‘boma’ to remain consistent

tion constitute a major source of revenue to the Maasai, especially in

with other academic studies of Maasai pastoralism (Bekure et al., 1991;

Lemek and on the northern Loita Plains. Groups of Maasai pool their

Homewood & Rodgers, 1991; Rutten, 1992).

land to establish ‘farming associations’, whilst local elites controlling

9

A small number of households are headed by women. Data provided much larger areas lease their land to commercial wheat farmers

by Rutten (1992) indicate that in six group ranches in eastern Maa- (Lamprey, 1984; Norton-Griffiths, 1995; Ottichilo, 2000; Serneels &

sailand, 22 of 478 households, or 4.6%, were headed by women. Lambin, 2001; Thompson & Homewood, 2002).

1002 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

Figure 3 A Maasai boma at Talek in 1986,

based on the former communal pattern, with

central enclosure for cattle, and peripheral

enclosures for sheep and goats. Photograph

taken in the early morning with herds

departing for grazing through separate

household gates.

Figure 4 A Maasai boma at Oltorotua in

2002, with cattle departing for grazing. This

boma shows the present trend towards frag-

mentation into separate household units,

with permanent corrugated-iron huts (left

and centre).

145/1/2/3/4).12 The airphotos were interpreted using a stere-

METHODS

osope (·4 magnification) or, where stereo-pairs were not

available, using a binocular microscope (·4 and ·8 magnifi-

Human settlement distribution

cation).

Table 1 summarizes the sources of data for this study. In order In all aerial photographs, resolution and scale was suffi-

to determine changes in pastoral use of the area, settlements cient to detect Maasai bomas, and to count the huts (Maa pl:

were mapped over a period of 50 years using a variety of enkajijik) within them. No boma was located in the same

methods. Early descriptions of settlement distributions in

southern Narok before 1960 are given in district and provincial

12

reports of the colonial administration. Within the study area, Negatives and prints of each set of photography were originally

Maasai bomas were mapped by interpretation of complete- stored at the Survey of Kenya in Nairobi. For this study, new prints

coverage aerial photography taken in 1950, 1961, 1967 and were produced for the years 1961, 1967 and 1974 for lab interpretation,

whilst interpretation of the 1950 photos took place directly at the

1974. These photographs, of scales varying from 1:30,000 to

Survey of Kenya. In the late 1980s, negatives and prints of most sets of

1:70,000, were originally taken to produce and update 1:50,000 photography were moved from the Survey of Kenya to the UK’s

scale topographic maps for the area (Y731 series, numbers Ordinance Survey in Southampton, England.

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1003

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

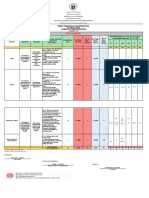

Table 1 A chronology of data sources used for the study

Huts/ People/ Human Sheep/

Year(s) Bomas boma hut population Wildlife Cattle goats Woodlands NDVI Details

1950 TAP TAP TAP Aerial photography scale 1:30,000

1961 TAP TAP TC TAP Stewart & Talbot (1962) Aerial

photography scale 1:50,000

1967 TAP TAP TAP Aerial photography scale 1:57,000

1968–72 S(O) SRF Programme of Serengeti

Research Institute begins

(Pennycuick, 1975)

1974 TAP TAP TAP Aerial photography scale 1:68,000

1977 S(K) S(K) S(K) Start of SRF Programme by

KREMU/DRSRS (Ottichilo, 2000)

1978 S(K) S(K) S(K)

1979 CEN CEN S(K) · 11 S(K) · 11 S(K) · 11 1979 Population Census

1980 S(K) S(K) S(K)

1981 S(K) · 3 S(K) · 3 S(K) · 3

1982 S(K) · 3 S(K) · 3 S(K) · 3

1983 SGR SAP SGR S(K) S(K) S(K) SGR, MVC Sample ground survey (Lamprey,

SAP 1984) Sample aerial photography,

scale 1:6000, 21% systematic

coverage

1984 S(K) S(K) S(K) MVC

1985 S(K) · 2 S(K) · 2 S(K) · 2 MVC

1986 S(K) · 3 S(K) · 3 S(K) · 3 MVC

1987 S(K) S(K) S(K) MVC

1988 MVC

1989 CEN CEN S(K) S(K) S(K) MVC 1989 Population Census

1990–97 S(K) S(K) S(K) MVC

1999 REC, SAP CEN CEN MVC Aerial survey,

distribution all bomas.

1999 Population Census

2000 S(K) S(K) S(K) MVC

2001 SAP/B SAP/B MVC Sample aerial

photography of bomas

2002 TGR TGR TGR TGR TGR

TAP, total count from aerial photography; TC, total count; S(O), systematic reconnaissance flight (SRF) by Serengeti Research Institute, analysis

based on ‘occupance’ of grid cells (Pennycuick, 1975); S(K), systematic reconnaissance flight (SRF) by Kenya Rangeland Ecological Monitoring Unit,

now DRSRS (see text); S(K), SRF carried out but data not available; SGR, sample ground count; SAP, sample, derived from strip-sample aerial

photography; SAP/B, sample photography bomas only; REC, aerial reconnaissance flight; TGR, total ground count; MVC, maximum value composite

NOAA-AVHRR NDVI data; CEN, national population census.

spot in consecutive years of photography, indicating that the Monitoring Unit (KREMU)13 conducted a photo-mission in

period of occupancy is less than 6 years (the minimum inter- 1983 to acquire vertical panchromatic and infra-red photo-

photo period). Abandoned il-Purko bomas are burned after a graphy at scale 1:6000 scale along sample strips spaced 10 km

3–4-month period of drying-out. Assuming a mean period of apart across the study area. This survey constituted a 21%

occupancy of 4 years, some 6–7% of bomas in the airphotos systematic sample of Koyake Group Ranch. Bomas ‘captured’

are unoccupied prior to burning. With their distinctive circle in the strips were used as the sample for determining huts/

of flat-roofed huts, the bomas were easily distinguished on boma in 1983.

airphotos from the seasonal livestock camps which have no In January and August 1999, systematic aerial surveys were

huts, or only small shelters. From the interpretation, bomas carried out by light aircraft at 13,500 m a.s.l. (approximately

were mapped onto 1:50,000 base maps for digitizing. 8000 feet above ground level) to map all bomas onto 1:50,000

After 1974 there is no complete coverage aerial photography. maps, and to obtain estimates of huts/boma. In September and

From 1983 onwards (the start of our fieldwork period)

settlement distributions were determined from aerial observa- 13

In the late 1980s, KREMU became the Department of Resource

tions, oblique aerial photography and systematic ground Surveys and Remote Sensing (DRSRS), which was recently integrated

surveys. As part of our study, the Kenya Rangeland Ecological into the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA).

1004 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

December 2001, a sample of bomas was photographed from opportunistic time-frame (Campbell & Borner, 1995), and

the air at first light to estimate livestock/hut ratios (see next cross-border counts could not easily be coordinated.

section). As part of this exercise huts were counted from the Early livestock counts in the Mara (for example from a

photos to crosscheck hut/boma estimates. Meanwhile, in veterinary survey of 1960) require cautious interpretation, as

separate exercises, detailed ground counts were made of livestock numbers cannot easily be referenced to particular

settlements, wildlife and livestock in November 1999 for part localities. Useful livestock distribution data for the Mara

of Koyake and the MMNR (Reid et al., 2001), and in rangelands are only available from 1977 onwards, when

November 2002 for a larger area including most of Koyake, KREMU began a programme of seasonal SRF surveys of

other adjacent group ranches and MMNR (Reid et al., 2003). wildlife and livestock in Narok District. The KREMU census

These data supplemented those of this study. zone covered the entire rangeland areas of Narok District and

Livestock camps are clearly visible in vertical aerial photo- (later) Trans-Mara District (Stelfox & Peden, 1981; Broten &

graphy, and they were interpreted and mapped from all of the Said, 1995; Ottichilo, 2000). Previous analyses of these data sets

complete-coverage airphoto series (1950–74). The 1983 verti- have been stratified on the basis of ‘ecological units’ (Stelfox

cal aerial photography provided a 21% systematic sample of et al., 1980)14 or for all group ranches combined (Broten &

livestock camps for estimating total camp numbers across Said, 1995; Ottichilo, 2000). We analysed raw KREMU SRF data

Koyake Group Ranch. However, mapping livestock camps from 1979 to 2000 using Jolly’s ‘Method II’ (Norton-Griffiths,

from oblique views on the ground or air proved problematic, 1978) to obtain population estimates specifically for Koyake

as the camps blend with adjacent thickets and bushlands. By Group Ranch (see Table 1). To check consistency of our Jolly II

1983 the density of camps had significantly declined across the analysis with other studies, population estimates were also re-

ranch (see section ‘Expansion of Maasai settlement’), and with calculated for all ranches. We compare the Koyake data with

the mapping problems described above, they were not total ground counts of wildlife and livestock conducted in 1999

systematically counted after this year. However, as a subsidiary and 2002 that covered most of the MMNR and Koyake Group

exercise of the 2002 count, an intensive aerial search was made Ranch (Reid et al., 2001, 2003).

for camps in a 96 km2 sample area in the Ilbaan woodlands To further reassess the accuracy of KREMU data, aerial

near Talek. Camp densities for this specific area could then be photographic surveys were conducted of a systematic sample

compared with all previous years of photography to determine of bomas in Talek, Olare Orok and Mara Rienda in September

trends. 2001 (dry season) and December 2001 (wet season). The

In our study, the seven years of settlement distribution data purpose was to count cattle in bomas before they had left for

(1950, 1961, 1967, 1974, 1983, 1999 and 2002), serve as grazing, and, by extrapolation of cattle/hut ratios, to recalcu-

‘reference years’ for the analysis of change in the Mara late the cattle population for the entire Koyake ranch as a

ecosystem over the last half-century. Population estimates comparison with SRF data.

derived from the airphotos and ground surveys were compared

with national census data of 1962, 1966, 1969, 1979, 1989 and

Rainfall and primary production

1999 (Morgan and Shaffer, 1966; CBS, 1979, 1989, 1999).

Whilst we recognize that the Maasai are notoriously difficult to Rainfall has been monitored sporadically at a number of sites

census, and that enumeration areas change from one census to throughout the Mara, but the most reliable and long-term

the next, these census data were useful for comparison with records are gathered at Narok, with monthly rainfall recorded

data from the settlement counts. since 1914. These data were obtained from the Kenya

Estimates of hut occupancy (people/hut) were derived Meteorological Department.

from interviews in 64 huts at Talek in 1983 (Lamprey, 1984). Vegetation growth conditions were determined using Nor-

These estimates were compared with those obtained in more malized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data, derived

recent studies in the Mara and elsewhere in Maasailand from the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AV-

(Coast, 2000). HRR) sensor on board the NOAA (National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration) series of satellites (Justice et al.,

1986). NDVI data are highly correlated with rainfall (Richard

Wildlife and livestock populations and distribution

& Poccard, 1998) and resultant vegetation production (Prince,

The first estimates of wildlife numbers in the ecosystem were 1991). For this study, NDVI data were obtained as decadal

obtained from aerial total counts on either side of the Kenya– (10 days) ‘maximum value composite’ data from sources on

Tanganyika border in the 1950s and early 60s (Pearsall, 1957; the Internet, for the period 1983 to present.15 For assessment

Swynnerton, 1958; Grzimek & Grzimek, 1960; Stewart &

Talbot, 1962). Following the development of the SRF 14

In the analysis of Stelfox et al. (1980), the ‘Mara ecological unit’

methodology at the Serengeti Research Institute (SRI) (Jolly, combined the MMNR with Koyake; data for Koyake could not be

1969; Norton-Griffiths, 1978, 1986; ILCA, 1981), monthly or disaggregated from their data sets.

seasonal wildlife censuses covering virtually the entire ecosys- 15

There is however, a critical gap in 1991/92, where NDVI values were

tem were conducted by SRI from 1969–73 (Pennycuick, 1975). suppressed by atmospheric aerosols deriving from the eruption of Mt

After 1973, SRFs of the Serengeti were conducted on a more Pinatubo (the ‘Pinatubo effect’).

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1005

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

1.100

1.000

5-Year average of rainfall (mm)

900

800

700

600

Figure 5 Long-term rainfall at Narok,

1919–99, indicated as a 5-year cumulative

500 average. Redrawn from Lamprey (1984) with

1919 1924 1929 1934 1939 1944 1949 1954 1959 1964 1969 1974 1979 1984 1989 1994 1999

recent data from Kenya Meteorological

Year Department.

of growing conditions in Koyake group ranch, a cluster of nine 40

pixels were averaged covering the central grazing area of the 35 Enkikwe

ranch. 30 Talek

25

Cover (%)

Ol Keju

Ronkai

RESULTS 20

15

Expansion of Maasai settlement 10

Lamprey & Waller (1990) describe pastoral movements and 5

ecological changes in the Mara in the years following the great 0

rinderpest pandemic of the 1890s, which devastated both wild 1945 1955 1965 1975 1985

and domestic ruminants. Their livestock herds decimated, Year

many Maasai died or took refuge with agricultural neighbours.

Figure 6 Changes in woodland cover in three areas of the Mara

In the early years of the twentieth century, the Mara was only

from 1950–83, measured by dot-grid analysis over five sample

used by Okiek (‘Dorobo’) hunter-gatherers. Without regular points in each area (from Lamprey, 1984): These areas are (a)

burning and browsing, Acacia bushland began to regenerate Enkikwe (Acacia gerrardii woodland) – note woodland recovery

across the area, bringing tsetse-flies and trypanosomiasis during the 1980s, (b) Talek ( Acacia–Commiphora woodland) and

(Woosnam, 1913; Lewis, 1934; Ford, 1971). (c) Ol Keju Ronkai inside the reserve (assumed formerly to be

In 1913 il-Purko Maasai living in the ‘Northern Maasai Acacia woodland, now completely cleared to grassland).

Reserve’ in Laikipia were resettled by the colonial administra-

tion in an enlarged Southern Maasai Reserve that included the

The main factors affecting the pattern of Maasai occupation

rangeland and highland areas of Narok (Sandford, 1919;

of the Mara over the twentieth century were climatic

Lamprey & Waller, 1990). Some il-Purko Maasai moved into

conditions and the presence of tsetse-flies (Lamprey & Waller,

the Mara settled at Talek – there are accounts of German cattle

1990). Tsetse-infested bushlands extended as the ‘fly-belt’

raids on Maasai bomas at Talek during the First World War

through much of the area corresponding to the MMNR. The

(Sandford, 1919, p. 121) – but they were soon forced

following discussion makes constant reference to rainfall and

northwards into the Lemek Valley by the tsetse expansion

trends in bushland cover. Figure 5 shows a 5-year cumulative

(Lewis, 1934; Beaumont, 1945). By the mid-1920s, Maasai

average of rainfall at Narok, for the period 1914–99. The figure

sectional areas had become more firmly established. The il-

shows a period of particularly high rainfall during the late

Purko inhabited the Lemek Valley (the only part of the Mara

1950s and early 1960s, the effect of which is discussed below.

free of ‘fly’), the Loita Plains and parts of the Mau foothills.

Figure 6 shows trends in woodland cover in the Mara from

The Siria Maasai returned to occupy the area above the Siria

1950 to 1983 (Lamprey, 1984). The removal of bushland and

escarpment16 and the Loita, weakened by conflict, withdrew

tsetse opened up the Mara to a rapid expansion of human

into the Loita hills to the east (Lamprey & Waller, 1990).

settlement.

The 1950 aerial photography revealed the continued

16 confinement of the Mara il-Purko Maasai to the Lemek

Following the rinderpest epidemic, many of the Siria Maasai had

taken refuge with Luo communities to the west, or with Okiek hunter- Valley (see Fig. 7). Although all bomas were located in the

gatherers in the forests. valley, the livestock camp distribution indicates that the

1006 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

Figure 7 Bomas (black circles) and

temporary livestock camps (open circles) in

1950, mapped from aerial photography. At

this time the Mara National Reserve,

managed by Kenya Royal National Parks,

was located to the west of the Mara River,

in the Mara triangle.

Maasai dispersed some stock into the plains south and west In the northern Mara the destruction of vegetation was

of Aitong, presumably on a seasonal basis. Meanwhile, in the monitored by the Tsetse Survey and Control Programme

late 1950s, as pressure on grazing resources increased in the (Langridge et al., 1970). In 1959 the programme marked 100

Lemek Valley, the administrative and veterinary authorities in trees (referred to as ‘tsetse resting places’) in each of four

Narok District embarked on a programme to expand the vegetation plots at Talek to assess change. The main species

available grazing area further south into the Mara woodlands. marked were Grewia spp., Cordia ovalis, Acacia spp. and

Research was conducted on tsetse, game and pasture at Commiphora spp. They returned to assess the plots in 1963,

Aitong and Talek17 (Langridge et al., 1970), and bush was and reported that ‘between 1961 and 1963 rainfall was very

cleared experimentally in trial areas (Narok District Devel- heavy throughout the district and produced a luxuriant grass

opment Plan, 1955). cover, which allowed bi- and tri-annual burning…. The very

In the late 1950s, the Maasai intensified their own efforts fierce fires caused accelerated destruction of the vegetation

to remove tsetse, by systematically burning the woodlands. with marked changes in numbers of trees and shrubs. In plot

Conditions over the period 1955–61 were particularly no. 1 only 53 of the original resting places were found again,

favourable for this activity, as rainfall had greatly increased and of these most had suffered extensive damage. In plot no. 2,

(see Fig. 5) and grass production was high. During this only 31 of the original marked places remained. In plot no. 3,

period, the grasslands could be burned as often as twice only six of the original resting places were found… The

within a season (Langridge et al., 1970). As a result, vegetation changes in the (Ilbaan) escarpment woodland were

woodlands were opened up across the Mara (Lamprey, due more to the actions of elephants than fire. In plot no. 4, 24

1984; Dublin, 1995). The decline was accelerated by elephant resting places had been smashed down to the ground and 16

activity. As areas outside the Serengeti-Mara became increas- had been burnt’ (Langridge et al., 1970, pp. 208–209). Thus

ingly settled in the 1950s and 60s, elephants moved into the between 1959 and 1963, 47–94% of trees and shrubs were lost

ecosystem, in large numbers, inflicting heavy damage on in the study plots.

woodlands (Game Department Annual Report, 1951; Lam- As woodlands were cleared, tsetse disappeared from much

prey et al., 1967; Glover & Trump, 1970; Langridge et al., of the Mara (Darling, 1960; Talbot & Talbot, 1963; Glover &

1970). Trump, 1970; Langridge et al., 1970), and in 1963 the Tsetse

Survey and Control Programme was closed (Lamprey &

17

Waller, 1990). By the early 1960s the Maasai were able to

Tsetse species found in the Mara are Glossina swynnertoni and

G. pallidipes (Lewis, 1934; Beaumont, 1945; Langridge et al., 1970). At

extend their livestock camps as far south as the Talek river,

Talek in 1959, 4% of the tsetse flies caught were found to be carriers of Ol Keju Ronkai stream and the Posee plain, whilst bomas

Trypanosoma congolense and T. vivax (Whiteside & Langridge, 1959). were established at Aitong and Bardamat (see Fig. 8). The

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1007

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

Figure 8 Bomas (black circles) and

temporary livestock camps (open circles) in

1961, mapped from aerial photography. In

the 1950s the Mara National Reserve was

managed by the Game Department as the

Maasai Mara Game Reserve (MMGR), and

in 1961 it was ‘transferred’ to Narok

District Council and designated a

‘county-council reserve’.

southwards expansion of the Maasai that began in the late Tanzanian border. Under early agreements between the Game

1950s was spearheaded by a wider dispersal of smallstock.18 Department and the Maasai District Council, Talek was

Of the Meta Plains between Keekorok and Talek, Talbot designated a ‘grazing area’ within the MMGR (Game Depart-

et al. (1961, pp. 30–31) reported that ‘there have been ment Annual Report, 1961; Lamprey, in prep.). Presumably,

increasing numbers of goats and sheep grazed in the area in this definition did not exclude settlement, for the 1967 aerial

tightly packed herds numbering over 2000 animals. The fine photographs show a single large boma at Talek, the first in this

condition of this area is due primarily to the tsetse fly which area for 50 years (see Fig. 9).

has kept Masai cattle out for 50 years’.19 Grimwood (1960, The Maasai population in the Mara increased rapidly after

p. 26) recorded that ‘sheep and goats were being grazed group ranch registration in 1970. By 1974, there were 10 bomas

further and further into the fly zone, and grass burning, at Talek (see Fig. 10), and the settlement localities of Lemek,

which had been carried out to improve grazing was Aitong, Koyage, Ol Kinyie, Talek and Ol Doinyo Narasha were

progressively destroying the bush, pushing back the tsetse now well-established. As large areas in the Narok highlands

fly and allowing cattle to follow on the heels of the smaller were sold or leased to outsiders for wheat cultivation during the

stock.’ 1970s and 80s, many Maasai families were displaced into the

In 1961 the MMNR, formally comprising only the ‘Mara more marginal ranches closer to MMNR (Duraiappah et al.,

Triangle’20 was re-declared a ‘District Council Game Reserve’, 2000). By 1983 there were some 27 bomas at Talek, and a new

and was greatly enlarged to take in the plains east of the Mara locality had been established at Mara Rienda by immigrants

River. The new Maasai Mara Game Reserve (MMGR) now from Mau Narok (Fig. 11). By 1999, virtually every part of

extended eastwards to the Sianna hills, and southwards to the Koyake within reach of permanent water had been occupied

(Fig. 12).

18

Figure 13 shows changes in the density of livestock camps

Sheep and goats are more tolerant to trypanosomiasis than cattle

in Koyake as a whole, and in a sample area in the Ilbaan

(Whitelaw, 1983), and may therefore be taken into tsetse areas during

the dry season, when fly densities are lower (Challier, 1982). woodlands near Talek. A significant feature is the great

19 increase in camps in the 1960s, associated with the southward

Lee and Martha Talbot pioneered the first wildlife research in the

Mara in the early 1960s, and conducted a landuse survey of the district wave of dispersal, followed by a decline in camp density after

in the late 1950s. 1974. With increasing sedentarization of the Maasai, most

20 grazing areas were now within daily grazing range of the

The Mara Triangle is the area of MMNR bordered on the east by the

Mara River, to the west by the Siria escarpment, and to the south by localities of Aitong, Talek and Mara Rienda. Furthermore, in

the Tanzania border. many parts of the central and northern plains, little woody

1008 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

Figure 9 Bomas (black circles) and tem-

porary livestock camps (open circles) in 1967,

mapped from aerial photography. The first

boma was established at Talek in 1966–67.

Figure 10 Bomas (black circles) and tem-

porary livestock camps (open circles) in 1974,

mapped from aerial photography. Note the

increasing number of bomas at Talek, and

the reduced number of temporary livestock

camps, particularly in the western areas.

The map shows the boundaries of the

group ranches (GRs), newly established in

1970. In 1973 the Maasai Mara Game Reserve

was re-gazetted under the Wildlife Animals

Protection Act, 1964, but continued to be

managed by the Narok County Council.

vegetation remained with which to build temporary camps. wildebeest. It is only in Ilbaan and Olare Sambu in the south

Western areas towards the Mara River were avoided by the that livestock camps remain a significant feature. Some

Maasai in the dry season, as these were favoured by migratory Acacia–Commiphora bushland (and tsetse) remained here,

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1009

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

Figure 11 Bomas in 1983, mapped from the

ground and from aerial reconnaissance

flights. Temporary livestock camps were

scattered at very low density by this time,

and were not mapped (see text). In 1976,

the ‘Maasai Mara Game Reserve’ was redes-

ignated the ‘Maasai Mara National Reserve’

(MMNR) under the Wildlife (Conservation

and Management) Act, 1976; the Act speci-

fied that districts shall continue to manage

their former ‘county-council’ game reserves.

The map shows the excisions from MMNR

at Talek and Mara Rienda; these sections

were officially degazetted in 1984.

Figure 12 Bomas in 1999, mapped from

aerial reconnaissance flights. Temporary

livestock camps were not mapped (see text).

1010 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

0.25 per hut was determined from a sample size of 64 huts in four

Koyake bomas at Talek in 1983 (see Fig. 14). This gave a mean of

0.20 Ilbaan

Livestock camps km–2

4.61 people/hut which is close to the estimate of 4.64 people/

hut given in the 1999 national census for Koyake (see Table 2),

0.15

which carefully specified the hut as the ‘household’, whilst

0.10

recognizing the potential absence of the household head on

Census Night.23 Thus in 1999 the average boma of 7.78 huts

0.05 will accommodate an estimated 35.9 people, closely compar-

able with the estimate of 36.1 calculated from the data of Coast

0.00 (2001). Figure 13 also shows ‘reference adults’ (RA) per hut,

1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005

on the crude estimation that children under 15 are measured

Year

as 0.7 RA. Using this estimate (see section ‘Pastoral Require-

Figure 13 Changes in density of livestock camps in Koyake ments on Koyake’), total RA may be calculated as 0.8 · pop-

GR from 1950 to 1983, and in a sample area at Ilbaan (96 km2) ulation, as observed in examples from Rutten (1992) and

from 1950 to 2002. McCabe et al. (1997).

Figure 15 presents frequency histograms of huts per boma

over the period 1950–99. In the Mara boma size remained

wildebeest avoided the more rocky terrain, and the area relatively stable at 10–12 huts from 1950 to 1983. The marginal

remained useful for the seasonal dispersal of sheep and increase in boma size in the 1974 photography is probably due

goats.21 to the immigration of Maasai families immediately after group

In general, bushlands in the Mara have continued to decline, ranch registration, and their inclusion into new bomas.

the canopy cover being reduced from 30–40% cover in 1961 to However, by 1999 bomas had decreased in size to a mean of

0–5% cover in 1983 (see Fig. 6). However, in 1983 in Enkikwe 7.78 ± 1.168 huts/boma (95% CL, n ¼ 79), with 1–4 huts/

there was some recovery of woodlands, dominated by single- boma as the class with the highest frequency.24 Figure 16 shows

species stands of Acacia gerrardii. This recovery can be the trend in boma size from 1950 to 1999. Today in the Mara,

attributed to increased grazing in the area by Maasai livestock, communal bomas are disappearing, and the family ‘home-

and the resulting suppression of fire due to reduction in stead’ of 1–2 households is emerging as the new form of

herbaceous biomass. Inside the MMNR frequent fires continue settlement. By November 2002, the number of huts per boma

to open up remaining thickets. in Koyake had fallen further to an average of 6.3 (Reid et al.,

2003).

In this study, as in others in Maasailand, the ‘household’

Maasai population and distribution

(Maa sing: olmarei) is defined as all those who use the gate of

Bomas and huts can be clearly interpreted on aerial photo- the household head (usually the husband), including wives,

graphs at the scale available for this study. However, airphotos children, elderly dependents and any dependent brothers and

provide no useful information on households, the primary wives on the husbands side (Bekure et al., 1991; Homewood &

unit for socio-economic analysis (Coast, 2000; Thompson, Rodgers, 1991; Coast, 2000). An analysis of hut/gate ratios at

2002), which may comprise several huts.22 Therefore, we Talek in 1982 gave an estimate of 10.42 people per olmarei, or

determine human population trends in Koyake on the basis of 3.4 olmarei per boma (Lamprey, 1984). This may be compared

people per hut, huts per boma, and total bomas in the group

ranch. 23

In the Kenya Population Censuses of 1989 and 1999, the term

Table 2 shows estimates for people per hut, people per

‘household’ is directly analogous to people/hut in pastoral polygynous

household and population age structure from various esti- societies such as the Maasai, as the census instructions to enumerators

mates in Maasailand, as recorded through field assessments clearly indicate: ‘In a polygamous marriage, if the wives are living in

and population censuses. In our study, the number of people separate dwelling units, and cook and eat separately, treat the wives as

separate households. Each wife with her children will therefore

constitute a separate household. The husband will be listed in the

household where he will have spent the Census Night’ (see CBS, 1989,

21

It might also be suggested that as livestock camps were used pri- 1999, Enumerators Instruction Manual, Section 32, p. app1–8). In

marily for the dispersal of sheep and goats, the decline in camps reflects censuses before 1989, it was clear that each wife would automatically

a decline in sheep and goat numbers. Talbot et al. (1961) record the count the male household head as part of her household, even if he was

presence of many herds numbering over 2000 animals on the Meta elsewhere. Thus people/hut estimates in the 1979 census are higher

plains and at Talek. Herds of this size are very rarely encountered than estimates from other sources (see Table 2). People/hut estimates

today. However, there is no reliable information available on small- were still high in 1989, but it is reasonable to assume that as this was

stock numbers before KREMU SRFs began in 1977. the first census in which the new rules above were applied, this was due

22 to enumeration difficulties. Apparently greater care was taken in the

The main physical representation of the ‘household’, the gate in the

1999 census to avoid this bias (see CBS, 1999).

boma fence, could only just be resolved on the 1950s photos of scale

24

1:30,000 (the largest scale of complete-coverage airphoto series), but The 2001 boma photography gives an estimate of 7.43 ± 1.589 huts/

interpretation was not consistent due to variations in image quality. boma (95% CL) for a smaller sample of 21 bomas.

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1011

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

Table 2 Estimates of hut occupancy, household size and population parameters in Maasailand from various sources

People per household Population

Area/ranch/section Source People per hut (household ¼ hh) £ 15 years old (%)

Ngorongoro (Tanzania) Arhem et al. (1981) 4.14 (n ¼ 28 huts) 52.6

Ngorongoro NCAA (1999) 4.55 (n ¼ 11,354 huts) 7.70 (n ¼ 6708 hh) 53.0

Samburu (Kenya) Spencer (1973) 6.75

Kaputei high potential Nestel (1986) 4.8

(Kenya)

Kaputei low potential Nestel (1986) 4.4

Kaputei Bekure et al. (1991) – 10.78 (n ¼ 326 hh)

Kaputei Rutten (1992) 6.66 (n ¼ 221 hh) 47.0

Loodokilani Rutten (1992) 10.51 (n ¼ 75 hh) 55.1

Matapato Rutten (1992) 10.02 (n¼204 hh) 51.0

Shompole (Kenya) Coast (2001) 9.6

Lemek/Osopuko Narok District – – 52.5

Annual Report (1950)

Koyake/Lemek CBS (1979) 5.6* – –

Koyake/Lemek CBS (1989) 5.52* (n ¼ 1675 huts) – 54.7

Koyake/Lemek CBS (1999) 4.64* (n ¼ 1485 huts) – 53.4

Lemek Lamprey (1984) 7.69 ± 0.853 (95% CL)

(n ¼ 54 gates)

Talek Lamprey (1984) 4.61 ± 0.422 10.52 ± 0.973 (95% CL) 56.0

(95% CL) (n ¼ 64 huts) (n ¼ 34 gates)

Talek Coast (2001) 12.9

*Huts (Maa sing: enkaji) are defined as ‘households’ in the national censuses of 1989 and 1999 (see text).

Data recalculated from Rutten’s (1992) Table 8.2, averaged for three Kaputei group ranches (Olkinos, Embolioi, Kiboko), one Loodokilani group

ranch (Elang’ata Wuas) and two Matapato group ranches (Lorngosua, Meto).

Table 3 indicates the number of bomas, huts, households

and estimated population of the study area and Koyake, from

1950 to 1999, whilst Fig. 17 graphically indicates the increase in

huts for Koyake only, and includes the 2002 ground count

estimate. Applying the equation for mean annualized growth

rate (Preston et al., 2001), we calculated that the human

population in Koyake has increased at the rate of 7.6% per

annum over the period 1950–99. From 1983 to 1999 the

annual growth rate has been 4.4%, resulting in a doubling of

the population every 15 years.

In general, the human population estimates obtained in our

aerial reconnaissance in 1999 are supported by other sources.

Figure 14 Histograms of persons and reference adults/hut in Our estimates of 1828 huts in 235 bomas are similar to those

64 huts at Talek in 1983 (Lamprey, 1984). A crude estimate of obtained in the ground counts of 1999 and 2002 (Reid et al.,

‘reference adults’ (RA) was derived by recording children under 2001, 2003), making allowance for the different extents of the

15 years as 0.7 · RA (see text). This gives a mean of 3.84 ± ground counting areas. The 1999 ground count omitted the

0.338 RA per hut (95% CL). eastern part of Koyake, but instead included Ol Chorro Oirowa

and parts of Lemek GR. Within this census zone 1507 huts

with the 12.9 people per olmarei and 2.8 olmarei per boma were counted in 246 bomas. A possible explanation for the

specifically for the Talek area indicated in recent research by small difference with the 1999 aerial counts is that observers

Coast (2001).25 Again it is inferred that at Talek boma size may have had difficulty in interpreting the boma as a distinct

(olmarei per boma) is decreasing, whilst household size is unit, when many bomas are breaking up into smaller, but

increasing. contiguous units (see Fig. 4). The 2002 ground count

estimated 2234 huts in 295 bomas in the 90% of Koyake that

25

Lamprey (1984) recorded that in the crowded environment of the

was counted (Reid et al., 2003).

Lemek Valley, the average household comprised 7.69 ± 0.853 people Our population estimates are also supported by those

(95% CL). obtained in national population censuses, although careful

1012 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

35 35

30 Year 1950 30 Year 1961

25 Mean huts/boma = 10.97 25 Mean huts/boma = 10.66

S D = 6.12 S D = 5.32

Frequency (%)

Frequency (%)

20 n = 33 20 n = 71

15 15

10 10

5 5

0 0

1–4 5–8 9–12 13–16 17–20 21–24 25–28 29–32 33–36 1–4 5–8 9–12 13–16 17–20 21–24 25–28 29–32 33–36

Huts per boma Huts per boma

35 35

30 Year 1967 30 Year 1974

Mean huts/boma = 10.27 Mean huts/boma = 11.78

25 25

S D = 6.76 S D = 6.09

n = 94 n = 124

Frequency (%)

Frequency (%)

20 20

15 15

10 10

5 5

0 0

1–4 5–8 9–12 13–16 17–20 21–24 25–28 29–32 33–36 1–4 5–8 9–12 13–16 17–20 21–24 25–28 29–32 33–36

Huts per boma Huts per boma

30 40

Year 1983 35 Year 1999

25

Mean huts/boma = 10.72 30 Mean huts/boma = 7.78

S D = 6.94 S D = 5.22

20

n = 29 (sample) 25 n = 79 (sample)

Frequency (%)

Frequency (%)

15 20

15

10

10

5

5

0 0

1–4 5–8 9–12 13–16 17–20 21–24 25–28 29–32 33–36 1–4 5–8 9–12 13–16 17–20 21–24 25–28 29–32 33–36

Huts per boma Huts per boma

Figure 15 Frequency histograms of huts/boma in the Mara study area, for all years of settlement counts. The trend is towards bomas

with fewer houses.

14 interpretation is required due to changes in the enumeration

Mean

13 areas between census years. A census in 1950 revealed that the

Mode

12 ‘Lemek subsection of the Purko’ totalled some 3900 people

11 (Narok District Annual Report, 1950). However, as the Purko

10

settlement area extended as far east as Ololunga (well outside

Huts/boma

the study area), probably half of this total, or 1900 Maasai

9

actually lived in the Lemek Valley. In a ground count in 1945,

8

Beaumont (1945) estimated 50 bomas in the Lemek Valley,

7 including that part lying outside the study area to the east.

6 From the 1950 airphotos, 32 bomas were counted in the Lemek

5 Valley (study area part), giving an estimate of 2100 people. In

4 the 1999 population census, Koyake Group Ranch incorpor-

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 ated two enumeration areas, Koyake and ‘Mararianda’ (Mara

Year Rienda), totalling 6889 people, and part of the Aitong

enumeration area with 2905 people (CBS, 1999). The 1999

Figure 16 Decline in boma size (huts per boma) from 1950 to estimate of 8500 people for Koyake Group Ranch, derived

1999. The error bars give the 95% CL of the mean, and the from the aerial settlement count, is therefore representative

dotted line the mode. The 2002 data point is from the 2002

(Table 3).

ground count (Reid et al., 2003).

Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1013

R.H. Lamprey and R.S. Reid

Table 3 Bomas, huts, households and population estimate for Koyake, 1950–99

Year Bomas in Bomas in Mean huts Total huts, Households Estimated

study area Koyake* per boma ± 95% CL§ Koyake Koyake populationà

1950 32 4 10.97 ± 2.169 44 19 202

1961 62 25 10.66 ± 1.259 267 118 1229

1967 90 27 10.31 ± 1.391 278 123 1283

1974 107 50 11.78 ± 1.082 589 261 2715

1983 195 84 10.72 ± 2.639 900 398 4151

1999 531 235 7.78 ± 1.168 1828 809 8428

*Koyake did not exist before 1970; this refers to the corresponding area.

Based on people/household (‘family’) at Talek ¼ 10.42 ± 0.605 (95% CL) (see text).

àBased on people/hut ¼ 4.61 ± 0.422 (95% CL) (see Table 2).

§Although 95% CL are indicated, all huts per boma distributions are skewed (see Fig. 15). Differences in years are best tested by the non-parametric

Kruskal–Wallis test, where X2 ¼ 26.3799, d.f. ¼ 5, P < 0.001.

2400 2,234

of Trans-Mara was so tsetse-infested as to be unusable for cattle

grazing (Humphrey, 1947). The next veterinary census con-

2000

1,828 ducted in 1960 by the Agricultural and Veterinary Department

(see Simon, 1963) gives an estimate of 191,000 cattle for the

Number of Huts

1600

census areas of ‘Sianna-Talek’ and the ‘Loita Plains’, which

1200 correspond with the ranches of Koyake, Ol Chorro Oirowa,

900

Lemek, Ol Kinyie and Siana now surrounding MMNR.

800 589

It is only after KREMU SRFs began in 1977 that cattle

267

400 numbers can be determined at the scale of the group ranch. We

44 278

re-analysed KREMU data for the period 1980–2000, using Jolly’s

0

Method II, to estimate cattle, sheep/goats, wildebeest (Conno-

1945 1955 1965 1975 1985 1995 2005

Year

chaetes taurinus mearnsi) and zebra (Equus quagga boehmi)

populations on Koyake. These population estimates are shown

Figure 17 Increase in number of huts in Koyake Group Ranch in Table 4. Jolly II estimates were also calculated for cattle on all

(or equivalent area before ranch registration in 1970), for the Mara ranches (Koyake, Lemek, Ol Kinyie and Siana). Figure 18

period 1950–2002. The 2002 data point is from the ground survey. shows livestock populations for all ranches and for Koyake from

1980 to 2000, rainfall at Narok for 1977–2000, and the NDVI for

Trends in livestock populations Koyake from 1983 to 2000 to indicate vegetation production.

The earliest cattle population estimate in the study area is Cattle numbers on all ranches vary from 80,000 to 180,000, as

provided by Sandford (1919, p. 103), who describes the confirmed by Broten & Said (1995) for their analysis of 1977–91

development of dams in Lemek Valley in 1914–16, at which KREMU data, but there has been no marked long-term increase

‘10,000 cattle were watered daily’.26 It is known that many cattle or decrease (Serneels & Lambin, 2001).

died during catastrophic droughts and locust ‘visitations’ during Livestock estimates for Koyake reflect the general trend for

the early 1930s (Lamprey & Waller, 1990), but a cattle census in all ranches. The Koyake cattle population increased to about

1939 revealed that across Narok District the cattle population 40,000 head in the late 1980s, following good rainfall and

had increased to 180,000, of which 87,000 were owned by the il- increased primary production. In the early 90s, poor rainfall

Purko (Narok District Annual Report 1939).27 At this time much resulted in a decline to about 25,000 head. A further period of

good rainfall in 1997/98, associated with ‘El Nino’, led to an

26

increase again to 40,000; this was followed by a massive ‘crash’

According to Sandford (1919), in 1917 the il-Purko Maasai, with a

in the catastrophic ‘La Nina’ drought of 1999/2000 that

population of 16,500 people, owned 375,000 cattle and over 1,000,000

sheep/goats. These estimates, if they can be relied on (see Broch-Due & reduced cattle numbers to about 14,000 head (Reid et al.,

Anderson, 1999), indicate that with 22 cattle per capita, the il-Purko 2001). Ground counts in 2002 showed that cattle populations

were remarkably wealthy in comparison with the situation today (see recovered rapidly again, with an estimated 27,500 head on

Section ‘Pastoralism as a livelihood on Koyake’). It is extraordinary Koyake (Reid et al., 2003). Meanwhile, over the 1990s the

that cattle herds had increased to this extent just 27 years after the

Maasai have increased their sheep and goat herds, usually a

rinderpest pandemic. Cattle raiding must have been a major factor in

il-Purko restocking. strategy in times of drought or hardship (Grandin, 1988;

27

Homewood & Rodgers, 1991). The contribution of sheep and

Given that the il-Purko population was estimated at 10,500 in 1950

goats to total livestock biomass increased from 7.1% in 1979 to

(Narok District Annual Report, 1950), it would appear that, with eight

cattle per capita, the il-Purko were still moderately affluent (see Section 9.9% in the late 1990s (see Table 5). With current trends this

‘Pastoralism as a livelihood on Koyake’). proportion may increase further.

1014 Journal of Biogeography 31, 997–1032, ª 2004 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Expansion of human settlement in Kenya’s Maasai Mara

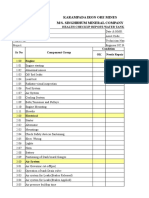

Table 4 Summary of cattle, sheep/goat, wildebeest and zebra estimates with standard errors (SE) for Koyake, derived from KREMU SRFs of

1980–2000 by Jolly Method II analysis

Cattle Sheep and goats Wildebeest Zebra

Date of survey Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE

01-Jul-80 16,880 8656 19,200 7693 1540 850 – –

09-Mar-81 6640 2718 9340 2541 10,140 6627 – –

27-Aug-81 20,840 7171 21960 9888 105,500 31,130 – –

27-Oct-81 11,300 5275 18,120 6708 79,960 21,262 – –

22-May-82 27,460 5277 11,980 7566 2280 748 – –

30-Aug-82 17,788 2420 21,788 9717 157,192 27,471 – –

06-Dec-82 54,774 23,591 31,830 14,981 1736 707 – –

24-Apr-85 49,408 16,071 38,586 11,344 3109 1247 4967 1084

28-Nov-85 20,822 7859 30,609 13,347 4688 1729 8257 1248

08-May-86 37,977 9013 31,480 13,864 1546 908 5872 1512

10-Aug-86 35,806 21,453 16,941 6826 32,664 8251 4293 1189

08-Nov-86 25,987 5181 25,592 10,129 13,668 4919 8306 2385

24-Apr-87 22,589 9389 22,660 14,318 2287 1825 6702 1779

12-May-89 40,745 15,030 20,213 10,840 1507 791 1560 325

13-Aug-90 44,858 24,736 16,312 10,716 127,252 75,401 12,482 2430

20-Apr-91 38,067 8302 24,858 10,237 3156 921 2199 427

12-Aug-91 38,651 7876 23,240 6358 55,987 11,629 6135 1468

14-Mar-92 19,581 4780 17,451 4760 6924 1776 22,401 3101

19-Aug-92 27,089 6390 23,067 9897 50,831 13,710 6965 2242

03-Nov-93 33,200 6348 17,367 5063 9530 1131 4628 884

15-May-94 18,165 8490 12,172 3838 1791 522 1995 949

27-Jul-96 8227 3108 10,346 4184 69,291 15,901 7934 1116

28-May-97 32,518 5857 24,149 4000 1073 467 3085 1610

19-Aug-97 46,392 9335 32,261 9713 24,273 15,041 8626 2606

21-Oct-00 7748 2679 60,603 16,589 16,507 5041 10,674 6294

Figure 19 shows that the Koyake cattle population lags to rainfall conditions. However, the SRF during the drought year

1–2 years behind the peaks and troughs of rainfall and primary of 2000 gives a high estimate of 244,000; during the prevailing

production, and demonstrates that 75% of the variation in cattle dire conditions Maasai of Koyake and other Narok ranches had

numbers on Koyake (wet-season population) is explained by no choice but to take some of their cattle to Trans-Mara.

rainfall in the previous 2 years. This confirms that, as with resident

wildebeest (Serneels & Lambin, 2001), rainfall is the limiting factor

Trends in migratory wildlife

for cattle in the Mara, and that the Maasai continue to maximize

their herds opportunistically in response to favourable conditions. In the early 1970s, Maasai moving southwards into the Mara

Dry-season cattle estimates show no relationship at all with plains following the eradication of tsetse met head-on with the