Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tsaousoglou P 2016 Diagnosis and Treatment of Ankyloglossia A Narrative Review and A Report of Three Cases

Uploaded by

Nhung Võ Thị MỹOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tsaousoglou P 2016 Diagnosis and Treatment of Ankyloglossia A Narrative Review and A Report of Three Cases

Uploaded by

Nhung Võ Thị MỹCopyright:

Available Formats

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

ORAL SURGERY

Phoebus

Tsaousoglou

Diagnosis and treatment of ankyloglossia:

A narrative review and a report of three cases

Phoebus Tsaousoglou, DDS, MSc, Dr Med Dent 1/Nikolaos Topouzelis, DDS, MSc, PhD2/Ioannis Vouros, DDS,

MSc, Dr Med Dent 3/Anton Sculean, DMD, MS, PhD, Dr Med Dent, Dr h c 4

Background: Ankyloglossia or tongue-tie is a congenital oral sia by means of frenuloplasty in three cases. Review: The

anomaly with short, tight, and thick lingual frenulum. It may be available evidence from the literature indicates that among

asymptomatic or can cause movement limitations of the neonates, children, and adults the prevalence of ankyloglossia

tongue, speech and articulation difficulties, breastfeeding diffi- is low and in some cases remains undiagnosed. The early clin-

culties in neonates, as well as periodontal and malocclusion ical assessment, diagnosis, and treatment are beneficial for the

problems. The etiopathogenesis of ankyloglossia is unknown; patients and their mothers. Conclusions: Frenuloplasty is a

it can occur either as a sole anomaly in the vast majority or in safe, quick, effective, and economical method and for this rea-

association with other craniofacial anomalies. Objectives: son the parents should not hesitate towards frenulum release.

The aims of this paper were (1) to provide a comprehensive More clinical studies are needed to confirm the benefits of the

review on the criteria for clinical assessment and diagnosis, surgical interventions and to compare the results with those

etiology and inheritance, and the therapeutic options of anky- obtained using nonsurgical therapy or with untreated cases.

loglossia; and (2) to demonstrate the treatment of ankyloglos- (Quintessence Int 2016;47:523–534; doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a36027)

Key words: ankyloglossia, frenuloplasty, surgical intervention, tongue-tie

The term “ankyloglossia” is derived from the Greek genioglossus muscles. It can present with different clin-

word “agkilos” for curved and “glossa” for tongue, and ical types, from a severe form with the tongue fused to

is also known as “tongue-tie”. In this paper the term the floor of the mouth to a milder form with only an

“ankyloglossia” will be used. Ankyloglossia, a congenital abnormally short and thick lingual frenulum.1-3 The

oral anomaly, is caused by short frenulum and/or short structure of the body of lingual frenulum is composed

of connective tissue.4 Normally, after birth and during

the first years of the child’s growth and development,

1 Periodontist, Department of Periodontology, School of Dental Medicine, Univer-

sity of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

the lingual frenulum recedes, but in some cases this

2 Professor and Chairman, Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, Aris- frenulum fails to recede or it appears very tight.5,6 As a

totle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. consequence, the mobility of the tongue is impaired in

3 Associate Professor, Department of Preventive Dentistry, Periodontology and

Implant Biology, School of Dentistry, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. a varying degree, from slight to severe impairment.

4 Professor and Chairman, Department of Periodontology, School of Dental Med- Ankyloglossia can be observed in neonates and infants

icine, Department of Periodontology, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

as well as in children and adolescents, but in some peo-

Correspondence: Dr Phoebus Tsaousoglou, Department of Periodon- ple this situation remains undiagnosed despite the

tology, School of Dental Medicine, University of Bern, Freiburgstrasse 7,

CH-3010 Bern, Switzerland. Email: phtsaouso@yahoo.com possible associated anatomic or functional problems.

VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016 523

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

There is a controversial issue in terms of the clinical ETIOLOGY AND INHERITANCE

significance of this anomaly. Some authors support that

ankyloglossia is most often asymptomatic whereas The exact etiology and pathogenesis of ankyloglos-

others support that it may cause problems such as sia is unknown. Ankyloglossia can occur either as a

infant breastfeeding difficulties (sore nipples, poor sole anomaly or in association with other craniofacial

infant weight gain, early weaning, number of sucks, anomalies. In 82% of ankyloglossia cases, this was

pause length between sucking),7-9 dyspnea from for- reported as a sole anomaly without other abnormalities

ward dislocation of the epiglottis and larynx,10,11 poor or diseases.18 However, some studies have related this

oral hygiene,12 prolonged nipple pain or mastitis of the entity with syndromes, such as X-linked cleft palate

mother, speech disorders, swallowing abnormalities,5,13 syndrome,19-22 Ehlers–Danlos syndrome,4,23 junctional

various mechanical problems (difficulty in licking the epidermolysis bullosa inversa,24 Kindler syndrome,25

lips, licking an ice cream cone, playing a wind instru- Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome,26 Van der Woude

ment), cuts beneath the tongue, orthodontic and syndrome,27 Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome,28 Smith–

orthopedic anomalies,14 diastasis of the mandibular Lemli–Opitz syndrome, and Opitz syndrome.29,30

incisors related to the short frenulum, difficulty in Ankyloglossia is possible to be manifested as a

“French” kissing,15 vocalization difficulties, and social result of mutations in T-box genes or from exposure to

issues related to the mobility of the tongue.3,16 Some teratogenic substances during pregnancy.22,31-33

problems, such as social embarrassment, cuts beneath It is suggested that a significant proportion of anky-

the tongue, and difficulty in “French” kissing, are most loglossia is inherited and specifically it seems to be

likely to manifest in the adolescence. There is a dis- autosomal dominance.34 There are two reports of a

agreement regarding swallowing abnormalities due to family with isolated ankyloglossia inherited as an auto-

ankyloglossia probably because the maturation of the somal dominant trait.35,36

swallowing mechanism differs across all age groups. In It is worth reporting that maternal cocaine use

babies, swallowing is infantile type; by the 2nd and 4th increased the risk of ankyloglossia by more than three

years of age it turns into a mature pattern. The per- times.37

sistence of the infantile swallowing pattern might be

due to the inability to elevate the tongue.5,13,17

In terms of speech difficulties in cases with ankylo-

EPIDEMIOLOGY

glossia, some children are reported to be able to The incidence of ankyloglossia is relatively rare as it is

develop normal speech whereas some develop speech referred from medical professionals. More than 70% of

insufficiencies as a result of articulation errors or diffi- these professionals report that the prevalence of anky-

culties.5,15 loglossia is low.38 In the literature, ankyloglossia among

The most common reason for surgical frenulum neonates and infants is presented with a prevalence

division was speech problems (64%), and the majority from 0.02% to 10.7%.3,8,34,37,39-42 This wide fluctuation is

of patients (84%) reported benefit from the oper- the result of the lack of a uniform definition, objective

ation.18 grading system, the differences in diagnosis among the

The aims of the present paper are: researchers, as well as the possibility of spontaneous

• to provide a comprehensive review on the criteria resolution with age. Among different ages, males seem

for clinical assessment and diagnosis, etiology and to be more affected than females, ranging from 4:1 to

inheritance, and the therapeutic options of ankylo- 1.7:1.34,39,42-45 Ankyloglossia is thought to be less com-

glossia mon in adults as compared to infants,46 leading some

• to demonstrate the treatment of ankyloglossia by to the hypothesis that certain cases of ankyloglossia

means of frenuloplasty in three cases. improve with age.16 No racial predilection seems to

524 VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

exist.37,39 A positive family history was noted in 10% to A protrusive chin or prognathism may be consid-

53% of the subjects.15,41,47,48 ered as a result of the low tongue position causing for-

The prevalence of speech anomalies in connection ward and downward pressure and favoring either man-

with ankyloglossia fluctuate from 1.1% in Spain to dibular hyperdevelopment or maxillary

48.8% in Brazil.49,50 hypodevelopment. 55-58 However, no significant correla-

High percentages of infants who experienced tion was found between dentofacial anomalies and

breastfeeding problems have been referred.3,41,48 A very ankyloglossia.49 The scientific data do not have the

recent retrospective study demonstrated that 66% of power to clarify if the ankyloglossia can be considered

newborns with breastfeeding difficulties had ankylo- a co-factor in the development of malocclusions, espe-

glossia.51 The degree of the breastfeeding difficulties cially Class III malocclusion. In a case report it was

among the relevant medical specialists varies. Lactation reported that frenectomy led to a favorable occlusion.57

consultants believe that ankyloglossia frequently In a case series study, it was suggested that ankyloglos-

causes breastfeeding difficulties, whereas 90% of pedi- sia in association with a Class III malocclusion resulted

atricians and 70% of otolaryngologists believe that in dentofacial anomalies in the maxillary arch.11 More

ankyloglossia never or rarely causes a feeding prob- clinical studies should be carried out in order to eluci-

lem.38 For every day of maternal pain during the initial date the correlation between malocclusion and ankylo-

3 weeks of breastfeeding there is a 10% to 26% risk of glossia.55

cessation of breastfeeding.52 Mothers breastfeeding Sometimes periodontal discrepancies such as a

infants with ankyloglossia have more nipple pain than diastema between the mandibular central incisors are

mothers feeding normal infants.3,42 Persistent nipple found as a result of the protrusion of the lingual frenu-

pain in women breastfeeding infants with ankyloglos- lum.

sia has been observed in a rate from 36% to 80%.3 In addition to the aforementioned clinical features,

another very frequent characteristic is speech difficul-

ties. Nevertheless, a recent systematic review found no

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS significant evidence regarding ankyloglossia as an etio-

The most important clinical features are described below. logic factor for speech problems.59

The tongue is often heart or V-shaped at its tip,

which is caused by tethering by the frenulum. Tongue

mobility in ankyloglossia, in general, is restricted. A

DIAGNOSIS

typical feature in cases with severe limitation of mobil- Diagnosis is based on clinical examination. The appear-

ity is the inability of the tongue to lick the lips. Its pro- ance and the mobility of the tongue, together with the

trusion is limited and the tip may not extend over the attachment, the insertion, and the shortness of the lin-

lower lip. In some cases, the tongue cannot protrude gual frenulum should be examined and evaluated.

more than 1 to 2 mm past the mandibular incisors.53 Its Several authors have reported that they checked the

elevation is also characteristically impaired, from a appearance and the mobility of the tongue with the

complete inability of elevation of the tongue to some Hazelbaker Assessment Tool.60,61 Also, the speech ability

degree of elevation. of the patient can be checked by the vocalization of

The frenulum appears abnormally short and it may some letters and words. The vocalization of certain

be thin and membranous or fibrous and thickened, words by the person can assist in the disclosure of pos-

with insertion (attachment) at or near the tongue tip on sible speech problems. Speech sounds that may be

one side and with high insertion (attachment) into the affected by impaired tongue tip mobility include con-

lingual gingivae on the other side.7,41 Lingual gingival sonants and sounds, such as /s/, /z/, /t/, /d/, /l/, /j/, /zh/,

recessions might be present in such cases.54,55 /ch/, /th/, and /dg/, with more frequent difficulty in

VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016 525

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

pronouncing /s/ and /r/.15,49,50,53,62 Last but not least, the less than 1 year of age or over 12 years of age; others,

whole appearance of the dentoalveolar structures that adulthood is the optimal timing of surgical repair;

should be checked for characteristics such as gingival and others, at any age.5,15,16,38,58,63,66-70 Contrary to these,

recession, diastema, and malocclusion. a recent review highlights the need for good evaluation

and selection in any case as in half of breastfeeding

babies problems may not occur in an older age.71 More-

CLASSIFICATION over, two recent studies found low evidence regarding

A standardized categorization of cases with ankyloglos- the association between surgical intervention of anky-

sia has been considered necessary in order to assess loglossia and breastfeeding improvement or

when a condition constitutes ankyloglossia and its non-breastfeeding difficulties.72,73

severity, as well as when surgical intervention is The first step in the management of ankyloglossia is

needed. However, there is not a unique classification in to consider the necessity or not of surgical intervention

the literature, and instead many scientists have tried to based on the possible associated problems: tongue

implement a measurement system for the degree of mobility, breastfeeding in neonates, speech, malocclu-

ankyloglossia. Therefore, a lot of classification systems sion, and gingival recession. Surgical intervention of

have been proposed. One of these is based on findings ankyloglossia can be carried out either without anes-

by Ruffoli et al,58 who clinically and morphofunctionally thesia or under local or, less often, general anesthesia.18

examined patients using two techniques, establishing Three mainly surgical, conventional techniques are

a classification and categorizing the severity of ankylo- described in the literature:38,53,74-76 frenotomy (frenulot-

glossia as mild, moderate, and severe. According to omy [partial excision of lingual frenulum]), frenectomy

Kotlow’s criteria, four classes (mild, moderate, severe, (frenulectomy [complete excision of lingual frenulum]),

and complete ankyloglossia) can be determined.1 A and frenuloplasty (various methods to release the

recent classification has been reported in which the tongue and correct the anatomic feature, such as hori-

tongue mobility limitation is divided in five degrees.63 zontal-to-vertical frenuloplasty and four-flap Z-frenu-

Another more complicated and extensive system for loplasty). The term frenotomy should be used when

assessment of ankyloglossia has been described by sutures were not utilized during releasing of frenulum.

Fernando.64 Moreover, children with ankyloglossia Instead, the term frenuloplasty should be used when

underwent evaluation of tongue mobility with two incisions and sutures are performed, such as in horizon-

measurement methods: tongue elevation and tongue tal-to-vertical and Z-frenuloplasty techniques.18 Other

protrusion.65 Also, Hazelbaker’s assessment tool for procedures are the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser,77-79

lingual frenulum function has been demonstrated as Nd:YAP laser,80 Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG laser,81 and argon

another method for assessment and surgical division plasma cutting electrodes.82 Comparing a diode laser

recommendation.60 and an Er:YAG laser, the latter was found to be superior

to the former in terms of anesthesia, namely the utiliza-

tion of Er:YAG was possible only with topical anesthesia

THERAPY without local anesthesia, but at the same time Er:YAG

No consensus exists about the optimal timing of surgi- presented more pain immediately postoperatively.83

cal intervention for ankyloglossia. Some authors have Less pain following intervention and fewer nutrition

supported that infancy, and prior to the development and speech complications were demonstrated with

of speech, is the most appropriate age for surgery; oth- Nd:YAG laser in relation to conventional surgical tech-

ers wait until a speech problem manifests, usually after niques (frenotomy, frenectomy, frenuloplasty).84 A lot

the age of 4 to 5 years; others, that is less effective in of therapists support the utilization of laser for lingual

older children; others, that is inappropriate for infants frenulum division because it is a more convenient tech-

526 VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

nique for the patients, and because there is less bleed- Rare complications have been found after frenot-

ing, no need for sutures, faster wood healing, and omy, frenectomy, and frenulopasty, such as excessive

minimum scar formation.80,81,83,85,86 On the other hand, bleeding, upper airway collapse, infection, diathermy

in a case series study it was presented that surgical burn of the lip, crying, ulcer under the tongue, lingual

techniques offered better organization of muscle fibers dysfunction, deglutitory anomalies, and recurrence of

during the healing period in comparison with laser and ankyloglossia as a result of scarring.5,13,38,48 Seldom, recur-

electrocautery techniques, although they were less rence of ankyloglossia can be caused by scarring, but

effective regarding the manipulation of tissues during when it occurs, the clinical manifestation is less intense

the procedure, bleeding, and postoperative pain.87 than before the first treatment. Recurrent ankyloglossia

The use of frenotomy for ankyloglossia has shown usually responds effectively to revision surgery.38

favorable effects according to outcomes of different There is controversy among therapists in terms of

studies.12 This type of surgical approach is a relatively the effects of ankyloglossia in speech and also the effi-

simple, safe, and cost-effective procedure, with appro- cacy of speech therapy. A large number of speech

priate results in a short time. Frenotomy is the thera- pathologists believe that surgical therapy is frequently

peutic approach of choice in newborns with ankylo- or always helpful in this condition.38 Otolaryngologists

glossia (for breastfeeding difficulties), dividing the believe, twice more so than pediatricians, that ankylo-

lingual frenulum with small scissors at the thinnest glossia may be associated with speech difficulties, and

portion of the frenulum. It is quick and relatively easy to recommend surgery.38 More and more scientists, espe-

accomplish with topical anesthesia, and in some cases cially the surgeons, suggest speech therapy with partic-

even without anesthesia. Usually it does not need local ular tongue exercises to be followed postoperatively.92

anesthesia because discomfort and bleeding is mini- Moreover, recently it has been shown that initiation of

mal.8,74,88,89 Breastfeeding improvement after frenulot- the exercises by the patient 1 week earlier might be

omy has also been reported.90 useful so that the patient and the tongue adapt to the

Frenuloplasty is the preferred procedure for chil- movements without any pain, which could be present

dren and adults, generally for most patients older than after intervention if the usual postoperative exercise

1 to 2 years of age. At this age the chances of scarring protocol is implemented.63

and recurrence are reduced. Frenuloplasty may be car- The recommended tongue exercises postopera-

ried out under general anesthesia for young children tively are as follows:15,47,53

before school age and uncooperative older patients or 1. Push tongue in and out of mouth.

under local anesthesia in a private practice for cooper- 2. Open the mouth as wide as possible and attempt to

ative school age children and adults. It is suggested touch the tip of the tongue to the back of the max-

that frenuloplasty, as opposed to frenotomy, may illary teeth.

decrease the risk of recurrence.91 Four-flap Z-frenu- 3. Move the tongue from one side of the mouth to the

loplasty has been found to be superior to horizon- other, without moving the jaw.

tal-to-vertical frenuloplasty in terms of tongue length, 4. Place food of choice on one side of mouth between

tongue protrusion, and articulation improvement.53 the cheek and back teeth. Using the tongue, move

Adequate frenulum division is more important than the food from one side of the mouth to the other

the used technique (frenuloplasty or frenotomy), and and then back again.

adequate division is easier to achieve under general 5. Consonant sounds of F, V, T, D, N, L, SH, S, ZH, R, and Z.

anesthesia.18

Regarding the need for reoperation, patients treated The above exercises should be performed from 1 week

under general anesthesia needed fewer reoperations postoperatively in five repetitions of each exercise,

than those operated with local or no anesthesia.18 three to five times per day, for 30 days.

VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016 527

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

a b c

d e f

g h i

Figs 1a to 1j Case 1: the patient before intervention, the surgical steps of the horizon-

tal-to-vertical frenuloplasty technique, and the follow-ups are depicted. (a and b) The

elevation and protrusion status of the patient’s tongue before surgery. (c) Hemostatic

forceps were used to clamp the frenulum and the division was carried out by performing

horizontal incisions above and below the forceps. In this case the submandibular ducts

were close to the lower incision, so this was performed very carefully. (d) The incision of

the frenulum. (e) In order to accomplish adequate release of the tongue, the frenulum

was incised as far as the genioglossus muscle, with very gentle partial division of the

muscle. (f) The borders of the wound were released before suturing. (g) The sutures in

j place. (h) One month after surgery. (i and j) Three months after surgery.

CASE REPORTS speech problems. Apart from the above, he was

referred for surgical treatment of ankyloglossia preven-

Case 1 tively in order to avoid potential future lingual gingival

An 8-year-old boy in mixed dentition was diagnosed recession of the mandibular central incisors (Fig 1).

with ankyloglossia. He had Angle Class II/I malocclusion

with crowding of the maxillary and mandibular anterior Case 2

teeth and severe overjet and overbite. The patient A 12-year-old boy was diagnosed with ankyloglossia.

underwent orthodontic treatment and wore a remov- He was in permanent dentition with malocclusion of

able functional appliance (activator). He had severe Angle Class I at the right side and Class II at the left side.

restriction of tongue mobility, with mastication and The mandibular anterior teeth presented with severe

528 VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

a b c

Figs 2a to 2f The patient before, during,

and after surgical intervention. (a and b)

The disclosure of tongue limitations during

elevation and protrusion assessment. (c)

The incision of the frenulum. (d) The

sutures in place. (e and f) Three months

d e f after surgery.

crowding, and a congenital lack of the maxillary lateral digestive problems related to ankyloglossia were

incisors was found. He underwent orthodontic therapy found. Tongue elevation was recorded by measuring

with fixed appliances. He presented severe restriction the interincisal distance by maximal mouth opening

of elevation and protrusion and generally of tongue while maintaining contact of the tongue tip with the

mobility. Vocalization problems were obvious as well. posterior surface of the central incisor teeth. Tongue

The clinical examination revealed ankyloglossia with protrusion was measured as the maximum extension of

thick and short frenulum and for this reason he was the tongue tip past the mandibular teeth. These two

referred for surgical treatment of ankyloglossia (Fig 2). measurements were made in millimeters. In order to

keep the records more representative, the assessment

Case 3 was made by measuring each patient and each one of

An 8-year-old girl was referred for management of the two clinical measurements (tongue elevation and

ankyloglossia by a pediatrician, general surgeon, and tongue protrusion) five times, calculating the mean

speech pathologist in order to facilitate the improve- value.

ment of her speech. The clinical examination presented Before any intervention, the patient’s parents were

moderate ankyloglossia with limitations of tongue informed in detail, and informed consent was obtained

mobility. She was in early mixed dentition with Angle for each patient’s surgery. Surgery was performed

Class II, Division 2 malocclusion, and she presented under local anesthesia, implementing frenuloplasty

with mild crowding of her mandibular anterior teeth with the horizontal-to-vertical technique. There were

and spacing of the maxillary anterior teeth (Fig 3). no surgical or postoperative complications. Follow-up

was performed 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months postop-

As far as the classification by Ruffoli et al58 is concerned, eratively. Patients were instructed to carry out recom-

regarding the distance between the incisal edges of the mended tongue exercises, as described above, for 1

maxillary and mandibular incisor, case 1 was classified month after surgery. After 3 months’ follow-up, signifi-

as severe whereas cases 2 and 3 were classified as mod- cant improvement was observed with increased

erate. However, the values of the last two cases were tongue movement (Table 1). Vocalization was signifi-

almost at the lowest level of the moderate category. No cantly improved in all cases with speech problems.

VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016 529

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

a b

Figs 3a to 3c The patient before and after incision of the lingual

frenulum. (a) The restriction of the tongue elevation with a thick

and short frenulum. (b) The sutures of the wound after frenuloplas-

c ty. (c) Three months after surgery.

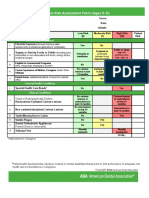

Table 1 The measurements of tongue elevation and tongue protrusion (mm) pre- and postoperatively

Tongue elevation Tongue protrusion

Postoperative Postoperative

Case Preoperative 1 week 1 month 3 months Preoperative 1 week 1 month 3 months

1 3 9 19 28 4 11 24 31

2 5 13 21 30 7 14 26 34

3 6 12 19 24 6 11 17 23

DISCUSSION improvement in 81% of the patients after frenu-

loplasty;15 a randomized prospective study found an

As far as current literature is concerned, there is neither improvement in between 40% and 91% of the patients,

a generally accepted classification system to describe depending on the operative method;53 a case series

ankyloglossia nor a unanimous system for treatment study watching the vocal cords with a laryngofiber-

management in terms of the indications, timing, and scope during phonation found that the vocal cords

method of surgical approach.3,41 However, positive after surgery could be seen in 55.3% of the cases

results after surgical treatment have been shown in instead of 14% before surgery.11 Likewise, the surgery

several studies. A prospective case study found an performance on the present cases had positive out-

530 VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

comes, with improvement in all cases. In terms of

tongue elevation and tongue protrusion assessments,

improvements of more than three times were found. A

prospective controlled trial demonstrated that the

measurements in millimeters of tongue elevation and

tongue protrusion when ankyloglossia was present Fig 4 A patient in whom the

ducts were not involved in the

were nearly half the length of control persons.7 lingual frenulum.

Many professionals have dealt with this topic,

including otolaryngologists, pediatricians, pediatric sur-

geons, dentists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, perio- plaque-induced inflammatory lesions, and/or general-

dontists, lactation consultants, and speech patholo- ized forms of destructive periodontal disease.95 High

gists. According to the literature, it is obvious that the muscle attachment and frenal pull, alveolar bone dehis-

significance of ankyloglossia, including clinical assess- cences, iatrogenic reasons, and other factors have been

ment, etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, and management recognized as secondary factors.94,96,97 The influence of

of ankyloglossia, should be a matter of interdisciplinary high frenal attachment in gingival recession is unclear

approach with some controversies among the scien- and there are disagreements in the literature.94,98-100 In

tists in the subsection issues. The broad referral status particular, there is not enough evidence to support the

from different professionals regarding the treatment of theory that a high frenal lingual attachment due to a

ankyloglossia is also supported by the three cases pre- short and high attached lingual frenulum can cause

sented in this report. The first case was referred by an lingual recession simultaneously with or without gingi-

otolaryngologist and orthodontist, the second by a val inflammation, and therefore, a direct association is

speech pathologist and orthodontist, and the third by not unambiguous. Additionally, a systematic review

pediatrician, general surgeon, and speech pathologist. found no evidence of association between gingival

In a considerable proportion of neonates, breast- recessions and ankyloglossia.55 However, some authors

feeding problems are noticed.3,41 The influence of anky- support that insertion of lingual frenulum in attached

loglossia on performing oral hygiene has often been a gingivae and papilla have strong association with gin-

matter of discussion. In consequence of poor oral and gival recession.81 There is a case report concerning lin-

dental hygiene due to the difficulties in cleaning, caries gual recession due to high lingual frenal attachment.54

lesions, periodontal pockets, and gingival recessions Recently, mild recession in lingual gingivae around

have been reported.92,93 In such cases the division of mandibular central incisors has been presented.87

frenulum is essential. Additionally, it has been suggested that as a result

Gingival recessions have been reported as a result of a strong lingual frenulum insertion in the attached

of short and thick lingual frenulum.94 As seen in Fig 1, gingivae, a diastema between the central incisors may

the frenulum of the patient in Case 1 was attached high develop.7,55,63,98,101 Consequently, it may be anticipated

to the lingual gingivae of the mandibular incisors, and that an open interdental space without any interproxi-

might have potentially contributed to the development mal contact might cause periodontal problems due to

of recession. This was an additional reason to release food impaction.102,103

the frenulum. In contrast, in the other two cases the A factor that has to be considered very carefully, in

frenulum was attached physiologically in the lingual cases where the frenulum is attached high in lingual

gingivae. Gingival recessions have a multifactorial etiol- gingivae, is whether the submandibular ducts interfere

ogy and may be caused by primary and secondary fac- or not with the frenulum. Sometimes the ducts are

tors. Main factors are associated with mechanical fac- located in the middle of the frenulum, a fact that makes

tors, such as toothbrushing trauma, and/or localized the division of the frenulum in surgery more difficult. In

VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016 531

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

the first case, the submandibular ducts are located in ies are either case reports or systematic reviews based

the middle of the lingual frenulum (Figs 1a and 1c), in on case reports. Moreover, there is high diversity and

contrast with another case where the ducts do not heterogeneity in methodology as well as in the charac-

interfere with the frenulum (Fig 4). teristics of the interventions.72,73 Therefore, more ran-

One of the possible complications of surgical pro- domized controlled trials are needed to confirm the

cedures is scarring at the incision site leading to recur- benefits of the surgical interventions on the various

rent ankyloglossia. In an effort to avoid this complica- problems observed in cases with ankyloglossia. Studies

tion, it is recommended that the patients perform comparing operated and not-operated cases with

tongue exercises for some months postoperatively. ankyloglossia are also required, taking into account

Specific exercises have been proposed by some authors obvious ethical issues.

and for this reason it is recommended to motivate both

patients and their parents to meticulously follow the

instructions for the exercises after surgery.7,15,53 It may

CONCLUSIONS

also be anticipated that tongue exercises could help Ankyloglossia is observed in a considerable number of

the patient to increase the range of tongue motion. infants, children, and adults. Even today there is major

Moreover, early mobilization of the tongue is encour- controversy among scientists regarding diagnosis,

aged to minimize scarring and tongue mobility. Usu- management, therapy, and subsequent clinical bene-

ally, signs of improvement in mobility are not observed fits. On the other hand, the surgical approach is a rela-

prior to the first or second month postoperatively, and tively simple and safe procedure, leading to satisfactory

this can extend to the third or fourth month. results in a short time.

The association between ankyloglossia and speech

problems is still not completely clear. The definition of

speech problems is mainly a subjective issue.7 In order

to clarify the effectiveness of the surgical treatment of REFERENCES

1. Kotlow LA. Ankyloglossia (tongue-tie): a diagnostic and treatment quandary.

ankyloglossia on the therapy of speech problems, more Quintessence Int 1999;30:259–262.

studies are needed. Furthermore, it would be of interest 2. Jamilian A, Fattahi FH, Kootanayi NG. Ankyloglossia and tongue mobility. Eur

Arch Paediatr Dent 2014;15:33–35.

to compare the treatment outcomes of speech prob-

3. Messner AH, Lalakea ML, Aby J, Macmahon J, Bair E. Ankyloglossia: Incidence

lems between surgical release of ankyloglossia and and associated feeding difficulties. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

2000;126:36–39.

nonsurgical treatment carried out by speech patholo-

4. Chu MW, Bloom DC. Posterior ankyloglossia: a case report. Int J Pediatr Oto-

gists. In all three cases described in this report, the rhinolaryngol 2009;73:881–883.

vocalization was substantially improved after surgery. 5. Wright J. Tongue-tie. J Paediatr Child Health 1995;31:276–278.

6. Bhattad MS, Baliga MS, Kriplani R. Clinical guidelines and management of

Regarding the prevalence of ankyloglossia, the fol- ankyloglossia with 1-year follow up: report of 3 cases. Case Rep Dent

lowing two points need to be emphasized: Firstly, the 2013;2013:185803.

7. Lalakea ML, Messner AH. Ankyloglossia: does it matter? Pediatr Clin North Am

prevalence of ankyloglossia is lower in studies looking 2003;50:381–397.

for general findings on oral mucosa than in studies 8. Hogan M, Westcott C, Griffiths M. Randomized, controlled trial of division of

tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. J Paediatr Child Health 2005;41:

looking for the prevalence of ankyloglossia 246–250.

alone.3,8,41,42,44,104-107 Secondly, the prevalence is lower in 9. Martinelli RL, Marchesan IQ, Gusmão RJ, Honório HM, Berretin-Felix G. The

effects of frenotomy on breastfeeding. J Appl Oral Sci 2015;23:153–157.

the studies investigating children, adolescents, or

10. Mukai S, Mukai C, Asaoka K. Ankyloglossia with deviation of the epiglottis and

adults than those investigating neonates, which may larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 1991;153:3–20.

suggest that mild forms of ankyloglossia are perhaps 11. Mukai S, Mukai C, Asaoka K. Congenital ankyloglossia with deviation of the

epiglottis and larynx: Symptoms and respiratory function in adults. Ann Otol

resolved with growth.3,8,39,41,42,44,49,104,108 Rhinol Laryngol 1993;102:620–624.

Systematic reviews have recently indicated a lack of 12. Segal LM, Stephenson R, Dawes M, Feldman P. Prevalence, diagnosis, and

treatment of ankyloglossia: methodologic review. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:

evidence on this topic, since the great majority of stud- 1027–1033.

532 VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

13. Sánchez-Ruiz I, González Landa G, Pérez González V, et al. Section of the 40. Friend GW, Harris EF, Mincer HH, Forg TL, Carruth KR. Oral anomalies in the

sublingual frenulum. Are the indications correct? Cir Pediatr 1999;12:161–164. neonate by race and gender in an urban setting. Pediatr Dent 1990;12:

14. Jang SJ, Cha BK, Ngan P, Choi DS, Lee SK, Jang I. Relationship between the 157–161.

lingual frenulum and craniofacial morphology in adults. Am J Orthod Dento- 41. Ballard JL, Auer CE, Khoury JC. Ankyloglossia: assessment, incidence, and

facial Orthop 2011;139:e361–e367. effect of frenuloplasty on the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatrics 2002;110:1–6.

15. Messner AH, Lalakea ML. The effect of ankyloglossia on speech in children. 42. Ricke LA, Baker NJ, Madlon-Kay DJ, DeFor TA. Newborn tongue-tie: preva-

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002;127:539–545. lence and effect on breastfeeding. J Am Board Fam Pract 2005;18:1–7.

16. Paradise JL. Evaluation and treatment for ankyloglossia. JAMA 1990;262:2371. 43. Sawyer DR, Taiwo EO, Mosadomi A. Oral anomalies in Nigerian children.

17. Peng CL, Jost-Brinkmann PG, Yoshida N, Chou HH, Lin CT. Comparison of Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1984;12:269–273.

tongue functions between mature and tongue-thrust swallowing: an ultra- 44. García-Pola MJ, García-Martín JM, González-García M. Prevalence of oral

sound investigation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004;125:562–570. lesions in the 6-year-old pediatric population of Oviedo (Spain). Med Oral

18. Klockars T, Pitkäranta A. Pediatric tongue-tie division: indications, techniques 2002;7:184–191.

and patient satisfaction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009;73:1399–1401. 45. Cinar F, Onat N. Prevalence and consequences of a forgotten entity: ankylo-

19. Björnsson A, Arnason A, Tippet P. X-linked cleft palate and ankyloglossia in an glossia. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;115:355–356.

Icelandic family. Cleft Palate J 1989;26:3–8. 46. Ketty N, Sciullo PA. Ankyloglossia with psychological implications. J Dent

20. Gorski SM, Adams KJ, Birch PH, Chodirker BN, Greenberg CR, Goodfellow PJ. Child 1974;41:43–46.

Linkage analysis of X-linked cleft palate and ankyloglossia in Manitoba Men- 47. Lalakea ML, Messner AH. Ankyloglossia: the adolescent and adult perspective.

nonite and British Columbia Native kindreds. Hum Genet 1994;94:141–148. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;128:746–752.

21. Forbes SA, Richardson M, Brennan L, et al. Refinement of the X-linked cleft 48. Griffiths DM. Do tongue ties affect breastfeeding? J Hum Lact 2004;20:

palate and ankyloglossia (CPX) localisation by genetic mapping in an Icelan- 409–414.

dic kindred. Hum Genet 1995;95:342–346. 49. GarcíaPola MJ, González García M, García Martín JM, Gallas M, Seoane Lestón

22. Braybrook C, Lisgo S, Doudney K, et al. Craniofacial expression of human and J. A study of pathology associated with short lingual frenum. ASDC J Dent

murine TBX22 correlates with the cleft palate and ankyloglossia phenotype Child 2002;69:59–62.

observed in CPX patients. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11:2793–2804. 50. Queiroz Marchesan I. Lingual frenulum: classification and speech interference.

23. De Felice C, Toti P, Di Maggio G, Parrini S, Bagnoli F. Absence of the inferior Int J Orofacial Myology 2004;30:31–38.

labial and lingual frenula in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Lancet 2001;357: 51. Pransky SM, Lago D, Hong P. Breastfeeding difficulties and oral cavity anom-

1500–1502. alies: the influence of posterior ankyloglossia and upper-lip ties. Int J Pediatr

24. Wright JT, Fine JD, Johnson LB, Steinmetz TT. Oral involvement of recessive Otorhinolaryngol 2015;79:1714–1717.

dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa inversa. Am J Med Genet 1993;47: 52. Schwartz K, d’Arcy H, Gillespie B, Bobo J, Longeway M, Foxman B. Factors

1184–1188. associated with weaning in the first 3 months postpartum. J Fam Pract 2002;

25. Hacham-Zadeh S, Garfunkel AA. Kindler syndrome in two related Kurdish 51:439–444.

families. Am J Med Genet 1985;20:43–48. 53. Heller J, Gabbay J, O’Hara C, Heller M, Bradley JP. Improved ankyloglossia

26. Neri G, Gurrieri F, Zanni G, Lin A. Clinical and molecular aspects of the Simpson correction with four-flap Z-frenuloplasty. Ann Plast Surg 2005;54:623–628.

GolabiBehmel syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1998;79:279–283. 54. Ewart NP. A lingual mucogingival problem associated with ankyloglossia: a

27. Burdick AB, Ma LA, Dai ZH, Gao NN. Van der Woude syndrome in two families case report. N Z Dent J 1990;86:16–17.

in China. J Craniofac Genet DevBiol 1987;7:413–418. 55. Suter VG, Bornstein MM. Ankyloglossia: facts and myths in diagnosis and

28. Patterson GT, Ramasastry SS, Davis JU. Macroglossia and ankyloglossia in treatment. J Periodontol 2009;80:1204–1219.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1988;65: 56. Couly G. The tongue, a natural orthodontic appliance ‘for better and for

29–31. worse’. Rev Orthop Dento Faciale 1989;23:9–17.

29. Meinecke P, Blunck W, Rodewald A. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Am J Med 57. Defabianis P. Ankyloglossia and its influence on maxillary and mandibular

Genet 1987;28:735–739. development: a seven year follow-up case report. Funct Orthod 2000;17:

30. Brooks JK, Leonard CO, Coccaro PJ Jr. Opitz (BBB/G) syndrome: Oral manifes- 25–33.

tations. Am J Med Genet 1992;43:595–601. 58. Ruffoli R, Giambelluca MA, Scavuzzo MC, et al. Ankyloglossia: a morphofunc-

31. Herr A, Meunier D, Müller I, et al. Expression of mouse Tbx22 supports its role tional investigation in children. Oral Dis 2005;11:170–174.

in palatogenesis and glossogenesis. Dev Dyn 2003;226:579–586. 59. Webb AN, Hao W, Hong P. The effect of tongue-tie division on breastfeeding

32. Morita H, Mazerbourg S, Bouley DM, et al. Neonatal lethality of LGR5 null mice and speech articulation: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol

is associated with ankyloglossia and gastrointestinal distension. Mol Cell Biol 2013;77:635–646.

2004;24:9736–9743. 60. Hazelbaker AK. The assessment tool for lingual frenulum function (ATLFF): use

33. Karahan S, Kul BC. Ankyloglossia in dogs: a morphological and immunohisto- in a lactation consultant private practice. Pasadena: Master’s Thesis, 1993.

chemical study. Anat Histol Embryol 2009;38:118–121. 61. Edmunds J, Hazelbaker A, Murphy JG, Philipp BL. Tongue-tie. J Hum Lact

34. Klockars T, Pitkäranta A. Inheritance of ankyloglossia (tongue-tie). Clin Genet 2012;28:14–17.

2009;75:98–99. 62. Ito Y, Shimizu T, Nakamura T, Takatama C. Effectiveness of tongue-tie division

35. Keizer D. Casuistische mededelingen dominant erfeljik ankyloglosson. Nederl for speech disorder in children. Pediatr Int 2015;57:222–226.

T Geneesk 1952;96:2203–2205. 63. Ferrés-Amat E, Pastor-Vera T, Ferrés-Amat E, Mareque-Bueno J, Prats-Armen-

36. Klockars T. Familial ankyloglossia (tongue-tie). Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol gol J, Ferrés-Padró E. Multidisciplinary management of ankyloglossia in

2007;71:1321–1324. childhood. Treatment of 101 cases. A protocol. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal

37. Harris EF, Friend GW, Tolley EA. Enhanced prevalence of ankyloglossia with 2016;21:e39–e47

maternal cocaine use. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1992;29:72–76. 64. Fernando C (ed). Tongue tie - from confusion to clarity: a guide to the diag-

38. Messner AH, Lalakea ML. Ankyloglossia: controversies in management. Int J nosis and treatment of ankyloglossia. Sydney: Tandem Publications, 1998.

Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2000;54:123–131. 65. Williams WN, Waldron CM. Assessment of lingual function when ankyloglos-

39. Jorgenson RJ, Shapiro SD, Salinas CF, Levin LS. Intraoral findings and anoma- sia (tongue-tie) is suspected. J Am Dent Assoc 1985;110:353–356.

lies in neonates. Pediatrics 1982;69:577–582. 66. Berg KL. Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) and breastfeeding: a review. J Hum Lact

1990;6:109–112.

VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016 533

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Tsaousoglou et al

67. Nicholson WL. Tongue-tie (ankyloglossia) associated with breastfeeding 88. Srinivasan A, Dobrich C, Mitnick H, Feldman P. Ankyloglossia in breastfeeding

problems. J Hum Lact 1991;7:82–84. infants: The effect of frenotomy on maternal nipple pain and latch. Breastfeed

68. Notestine G. The importance of the identification of ankyloglossia (short lin- Med 2006;1:216–224.

gual frenulum) as a cause of breastfeeding problems. J Hum Lact 1990;6: 89. Wallace H, Clarke S. Tongue tie division in infants with breast feeding difficul-

113–115. ties. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2006;70:1257–1261.

69. Catlin FI, De Haan V. Tongue-tie. Arch Otolaryng 1971;94:548–557. 90. Geddes DT, Langton DB, Gollow I, Jacobs LA, Hartmann PE, Simmer K. Frenu-

70. Warden PJ. Ankyloglossia: a review of the literature. Gen Dent 1991;39: lotomy for breastfeeding infants with ankyloglossia: effect on milk removal

252–253. and sucking mechanism as imaged by ultrasound. Pediatrics 2008;122:

e188–e194.

71. Power RF, Murphy JF. Tongue-tie and frenotomy in infants with breastfeeding

difficulties: achieving a balance. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:489–494. 91. Gray SD, Parkin JL. Congenital malformations of the mouth and pharynx. In:

Bluestone CD, Stool SE, Kenna MA (eds). Pediatric Otolaryngology, 3rd ed.

72. Chinnadurai S, Francis DO, Epstein RA, Morad A, Kohanim S, McPheeters M.

Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1996:989–991.

Treatment of ankyloglossia for reasons other than breastfeeding: a systematic

review. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1467–e1474. 92. Sane VD, Pawar S, Modi S, Saddiwal R, Khade M, Tendulkar H. Is use of laser

really essential for release of tongue-tie? J Craniofac Surg 2014;25:e279–e280.

73. Francis DO, Krishnaswami S, McPheeters M. Treatment of ankyloglossia and

breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1458– 93. Carmen F (ed). Tongue tie, from confusion to clarity. Sydney: Tandem Publi-

e1466. cations, 1998.

74. Kupietzky A, Botzer E. Ankyloglossia in the infant and young child: clinical 94. Trott JR, Love B. An analysis of localized gingival recession in 766 Winnipeg

suggestions for diagnosis and management. Pediatr Dent 2005;27:40–46. High School students. Dent Pract Dent Rec 1966;16:209–213.

75. Velanovich V. The transverse-vertical frenuloplasty for ankyloglossia. Mil Med 95. Wennström JL, Zucchelli G, Pini Prato GP. Mucogingival therapy: Periodontal

1994;159:714–715. plastic surgery. In: Lang NP, Lindhe J (eds). Clinical Periodontology and

Implant Dentistry, 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard Publishing, 2008:

76. Brinkmann S, Reilly S, Meara JG. Management of tongue-tie in children: a

955–1028.

survey of paediatric surgeons in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2004;40:

600–605. 96. Löst C. Depth of alveolar bone dehiscences in relation to gingival recessions.

J Clin Periodontol 1984;11:583–589.

77. Bullock N Jr. The use of the CO2 laser for lingual frenectomy and excisional

biopsy. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1995;16:1118,1120,1122–1123. 97. Lindhe J, Nyman S. Alterations of the position of the marginal soft tissue fol-

lowing periodontal surgery J Clin Periodontol 1980;7:525–530.

78. Fiorotti RC, Bertolini MM, Nicola JH, Nicola EM. Early lingual frenectomy assist-

ed by CO2 laser helps prevention and treatment of functional alterations 98. Stoner JE, Mazdyasna S. Gingival recession in the lower incisor region of

caused by ankyloglossia. Int J Orofacial Myology 2004;30:64–71. 15-year-old subjects. J Periodontol 1980;51:74–76.

79. Puthussery FJ, Shekar K, Gulati A, Downie IP. Use of carbon dioxide laser in 99. Powell RN, McEniery TM. A longitudinal study of isolated gingival recession in

lingual frenectomy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011;49:580–581. the mandibular central incisor region of children aged 6–8 years. J Clin Peri-

odontol 1982;9:357–364.

80. De Santis D, Gerosa R, Graziani PF, et al. Lingual frenectomy: a comparison

between the conventional surgical and laser procedure (Epub ahead of print, 100. Younes SA, El Angbawi MF. Gingival recession in the mandibular central

1 Aug 2013). Minerva Stomatol. incisor region of Saudi schoolchildren aged 10–15 years. Community Dent

Oral Epidemiol 1983;11:246–249.

81. Lamba AK, Aggarwal K, Faraz F, Tandon S, Chawla K. Er, Cr:YSGG laser for the

treatment of ankyloglossia. Indian J Dent 2015;6:149–152. 101. Priyanka M, Sruthi R, Ramakrishnan T, Emmadi P, Ambalavanan N. An over-

view of frenal attachments. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2013;17:12–15.

82. Verco PJ. Case report and clinical technique: Argon beam electrosurgery for

tongue ties and maxillary frenectomies in infants and children. Eur Arch Pae- 102. Larato DC. Relationship of food impaction to interproximal intrabony lesions.

diatr Dent 2007;8:15–19. J Periodontol 1971;42:237–238.

83. Aras MH, Göregen M, Güngörmüş M, Akgül HM. Comparison of diode laser 103. Jernberg GR, Bakdash MB, Keenan KM. Relationship between proximal tooth

and Er:YAG lasers in the treatment of ankyloglossia. Photomed Laser Surg open contacts and periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1983;54:529–533.

2010;28:173–177. 104. Sedano HO, Carreon Freyre I, Garza de la Garza ML, et al. Clinical orodental

84. Kara C. Evaluation of patient perceptions of frenectomy: a comparison of abnormalities in Mexican children. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989;68:

Nd:YAG laser and conventional techniques. Photomed Laser Surg 2008;26: 300–311.

147–152. 105. Flinck A, Paludan A, Matsson L, Holm AK, Axelsson I. Oral findings in a group

85. Olivi G, Signore A, Olivi M, Genovese MD. Lingual frenectomy: functional of newborn Swedish children. Int J Paediatr Dent 1994;4:67–73.

evaluation and new therapeutical approach. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2012;13: 106. Vörös-Balog T, Vincze N, Bánóczy J. Prevalence of tongue lesions in Hungarian

101–106. children. Oral Dis 2003;9:84–87.

86. Junqueira MA, Cunha NN, Costa e Silva LL, et al. Surgical techniques for the 107. Mumcu G, Cimilli H, Sur H, Hayran O, Atalay T. Prevalence and distribution of

treatment of ankyloglossia in children: a case series. J Appl Oral Sci 2014;22: oral lesions: A cross sectional study in Turkey. Oral Dis 2005;11:81–87.

241–248. 108. Sedano HO. Congenital oral anomalies in Argentinian children. Community

87. Reddy NR, Marudhappan Y, Devi R, Narang S. Clipping the (tongue) tie. J Dent Oral Epidemiol 1975;3:61–63.

Indian Soc Periodontol 2014;18:395–398.

534 VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 6 • JUNE 2016

Copyright of Quintessence International is the property of Quintessence Publishing Company

Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv

without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- 3D Printing in Restorative Dentistry EbookDocument91 pages3D Printing in Restorative Dentistry Ebookvaleriu vataman100% (1)

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument2 pagesConceptual FrameworkRheanne Gonzaga84% (37)

- 1000 Mcqs - Periodontics Plus September 2014 McqsDocument16 pages1000 Mcqs - Periodontics Plus September 2014 McqsSelvaArockiam86% (7)

- A Review of Molar Distalisation Techniqu PDFDocument7 pagesA Review of Molar Distalisation Techniqu PDFbubuvulpeaNo ratings yet

- 5th Year MCQ 2nd SemesterDocument35 pages5th Year MCQ 2nd Semestermdio midoNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Pathway For Complete Immediate Denture TherapyDocument18 pagesA Clinical Pathway For Complete Immediate Denture TherapyPragya PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Epilepsy Aphasias: Landau Kleffner Syndrome and Rolandic EpilepsyFrom EverandThe Epilepsy Aphasias: Landau Kleffner Syndrome and Rolandic EpilepsyNo ratings yet

- Health and Dental Action Plan Sy 16 17Document5 pagesHealth and Dental Action Plan Sy 16 17Hazeline ReyNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and Palate New ApproachDocument115 pagesCleft Lip and Palate New ApproachsoorajNo ratings yet

- Cleft of Lip and Palate - A Review - PMCDocument10 pagesCleft of Lip and Palate - A Review - PMCDr Abhigyan ShankarNo ratings yet

- Running Head: FRENECTOMIES 1Document9 pagesRunning Head: FRENECTOMIES 1api-522555065No ratings yet

- Carillas CeramicaDocument569 pagesCarillas Ceramicaqhmyjzx4ptNo ratings yet

- Walsh 2017Document8 pagesWalsh 2017Clara CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Tongue Tie (Ankyloglossia) : OtolaryngologyDocument4 pagesTongue Tie (Ankyloglossia) : OtolaryngologyDhia UlfajriNo ratings yet

- Lauren La Lake A 2002Document5 pagesLauren La Lake A 2002Arif oktavianNo ratings yet

- Treatment of AnkyloglossiaDocument10 pagesTreatment of Ankyloglossiacvdk8dc8sbNo ratings yet

- A Case Series of Anterior and Posterior Tongue TiesDocument4 pagesA Case Series of Anterior and Posterior Tongue TiesTrung Sơn LêNo ratings yet

- PCH 07269Document2 pagesPCH 07269drghempikNo ratings yet

- Walsh 2019Document17 pagesWalsh 2019madhumitha srinivasNo ratings yet

- Anquiloglosia 2Document9 pagesAnquiloglosia 2trilceNo ratings yet

- Tongue-Tie: Incidence and Outcomes in Breastfeeding After Lingual Frenotomy in 2333 NewbornsDocument7 pagesTongue-Tie: Incidence and Outcomes in Breastfeeding After Lingual Frenotomy in 2333 NewbornsMarco Saavedra BurgosNo ratings yet

- Labioskisis Dan Palatoskisis: Pembimbing: Dr. Utama Abdi Tarigan, SP - Bp-Re (K)Document35 pagesLabioskisis Dan Palatoskisis: Pembimbing: Dr. Utama Abdi Tarigan, SP - Bp-Re (K)yenny purba0% (1)

- Ankyloglossia Facts and Myths in Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument16 pagesAnkyloglossia Facts and Myths in Diagnosis and TreatmentJuan Sierra ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Oral Abnormalities in A Turkish Newborn PopulationDocument11 pagesPrevalence of Oral Abnormalities in A Turkish Newborn PopulationReinaldo MeléndrezNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Frenulotomy in Infants With AnkyloglossiaDocument4 pagesBenefits of Frenulotomy in Infants With Ankyloglossiaadrian bouzasNo ratings yet

- Instrumental Assessment of Pediatric DysphagiaDocument12 pagesInstrumental Assessment of Pediatric DysphagiaCarolina Lissette Poblete BeltránNo ratings yet

- 2007 Klockars Familial Ankyloglossia Tongue TieDocument4 pages2007 Klockars Familial Ankyloglossia Tongue TieCarlos CarrascoNo ratings yet

- Ankyloglossia and Other Oral TiesDocument17 pagesAnkyloglossia and Other Oral Tiesdikiprestya391No ratings yet

- Assessment and Management of Hearing LosDocument12 pagesAssessment and Management of Hearing LosmartaNo ratings yet

- Oral Path Log of Literature - Whitney Van KampenDocument10 pagesOral Path Log of Literature - Whitney Van Kampenapi-663596469No ratings yet

- Ejpd 2017 4 10Document7 pagesEjpd 2017 4 10Rafa LopezNo ratings yet

- Classification, Epidemiology, AndgeneticsoforofacialcleftsDocument15 pagesClassification, Epidemiology, AndgeneticsoforofacialcleftsCristian JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Genetics of Cleft Lip Andor Cleft Palate AssociatiDocument14 pagesGenetics of Cleft Lip Andor Cleft Palate AssociatiFauzia Latifah SupriyadiNo ratings yet

- LabiopalatoschisisDocument21 pagesLabiopalatoschisisOna AkyuwenNo ratings yet

- Solis Pazmino2020Document6 pagesSolis Pazmino2020Fábio LopesNo ratings yet

- Oral Development PathologyDocument6 pagesOral Development PathologyKathyWNo ratings yet

- Cysts of The Jaws in Pediatric Population: A 12-Year Institutional StudyDocument6 pagesCysts of The Jaws in Pediatric Population: A 12-Year Institutional StudyAndreas SimamoraNo ratings yet

- Dysphonia in Children: S Ao Paulo, BrazilDocument4 pagesDysphonia in Children: S Ao Paulo, BrazilVenny SarumpaetNo ratings yet

- Tongue Tie AAPD 2004 Classification, TreatmentDocument7 pagesTongue Tie AAPD 2004 Classification, TreatmentDilmohit SinghNo ratings yet

- Tongue TieDocument4 pagesTongue TiedrpretheeptNo ratings yet

- Policy On Management of The Frenulum inDocument6 pagesPolicy On Management of The Frenulum inLaura Sánchez LoperaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Anatomy 2019 Mills Defining The Anatomy of The Neonatal Lingual FrenulumDocument12 pagesClinical Anatomy 2019 Mills Defining The Anatomy of The Neonatal Lingual FrenulumDiana ChavezNo ratings yet

- Macroglossia PDFDocument7 pagesMacroglossia PDFpaolaNo ratings yet

- Syndromes and Anomalies Associated With CleftDocument6 pagesSyndromes and Anomalies Associated With CleftrobertaNo ratings yet

- Salivary Mucoceles in Children and Adolescents A Clinicopathological StudyDocument5 pagesSalivary Mucoceles in Children and Adolescents A Clinicopathological StudyxxxNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Diagnosis of Facial Anomalies (Diagnosis Usg Untuk Kelainan Wajah)Document7 pagesUltrasound Diagnosis of Facial Anomalies (Diagnosis Usg Untuk Kelainan Wajah)Puspita SariNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and PalateDocument115 pagesCleft Lip and PalateDavid OdhiamboNo ratings yet

- DisfoniaDocument5 pagesDisfoniaRosario Crisóstomo PinochetNo ratings yet

- Auditory ERPs Reveal Brain Dysfunction in Infants With PlagiocephalyDocument6 pagesAuditory ERPs Reveal Brain Dysfunction in Infants With PlagiocephalychiaraNo ratings yet

- Giovani 2016Document5 pagesGiovani 2016Marina Miranda MirandaNo ratings yet

- Wa0002Document4 pagesWa0002ninaNo ratings yet

- Grechi - 2008 - Bruxism in Children With Nasal ObstructionDocument6 pagesGrechi - 2008 - Bruxism in Children With Nasal Obstructioncarolina marpaungNo ratings yet

- 2021 Martinelli Effect of Lingual Frenotomy On Tongue and Lip Rest PositionDocument6 pages2021 Martinelli Effect of Lingual Frenotomy On Tongue and Lip Rest PositionYesenia PaisNo ratings yet

- Eating and Swallowing Disorders in Children With Cleft Lip Andor Palate - 2022Document9 pagesEating and Swallowing Disorders in Children With Cleft Lip Andor Palate - 2022Tânia DiasNo ratings yet

- Cleft PalateDocument7 pagesCleft PalateAhmadabubasirNo ratings yet

- Plastic Surgery Considerations PDFDocument3 pagesPlastic Surgery Considerations PDFFlávia MateusNo ratings yet

- Tongue: Tie and Frenotomy in The Breastfeeding NewbornDocument7 pagesTongue: Tie and Frenotomy in The Breastfeeding Newbornlaidasilva26No ratings yet

- Orthodontics/Craniofacial Growth and Development Oral PresentationDocument14 pagesOrthodontics/Craniofacial Growth and Development Oral PresentationAnye PutriNo ratings yet

- Down SyndromeDocument3 pagesDown SyndromeIdelia GunawanNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Dental Journal: Finger Sucking Callus As Useful Indicator For Malocclusion in Young ChildrenDocument6 pagesPediatric Dental Journal: Finger Sucking Callus As Useful Indicator For Malocclusion in Young Childrenortodoncia 2018No ratings yet

- Laryngomalacia and Swallowing Function in ChildrenDocument7 pagesLaryngomalacia and Swallowing Function in ChildrenmelaniaNo ratings yet

- Ankyloglossia (Tongue-Tie) in Infants and Children - UpToDateDocument24 pagesAnkyloglossia (Tongue-Tie) in Infants and Children - UpToDateConsulta Médica AriasNo ratings yet

- JSHD 3902 115-1Document18 pagesJSHD 3902 115-1szeho chanNo ratings yet

- Bjorl: Cephalometric Evaluation of The Oropharyngeal Space in Children With Atypical DeglutitionDocument6 pagesBjorl: Cephalometric Evaluation of The Oropharyngeal Space in Children With Atypical DeglutitionJudith Alexandra Castro GaeteNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology: Mark W. Steehler, Matthew K. Steehler, Earl H. HarleyDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology: Mark W. Steehler, Matthew K. Steehler, Earl H. HarleyJohan Sebastian Perea PalaciosNo ratings yet

- BurgDocument16 pagesBurgGrazyele SantanaNo ratings yet

- Dysphonia in Children: Journal of Voice: Official Journal of The Voice Foundation July 2012Document5 pagesDysphonia in Children: Journal of Voice: Official Journal of The Voice Foundation July 2012Nexi anessaNo ratings yet

- BruxismmDocument55 pagesBruxismmsahghanshyam9160No ratings yet

- Gender Differences in The Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontal Disease: The Hisayama StudyDocument1 pageGender Differences in The Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontal Disease: The Hisayama StudyritolutoNo ratings yet

- Irigasi 3.8% SDFDocument5 pagesIrigasi 3.8% SDFatmokotomoNo ratings yet

- Cambra PDFDocument2 pagesCambra PDFDaniel Esteban Veas GálvezNo ratings yet

- Inter-Tukang Gigi1Document6 pagesInter-Tukang Gigi1Langit DeanNo ratings yet

- Mounting:: The Laboratory Procedure of Attaching Cast To AnDocument11 pagesMounting:: The Laboratory Procedure of Attaching Cast To AnDr.Maher MohammedNo ratings yet

- Maxillofacial Prosthodontics: Ghassan G. Sinada, Majd Al Mardini, Marcelo SuzukiDocument5 pagesMaxillofacial Prosthodontics: Ghassan G. Sinada, Majd Al Mardini, Marcelo SuzukiThe Lost GuyNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Obturation of The Root Canal SystemDocument9 pagesContemporary Obturation of The Root Canal SystemAli Al-QaysiNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Three Methods of Orthodontic Anchorage: A Prospective StudyDocument7 pagesComparison of Three Methods of Orthodontic Anchorage: A Prospective StudyJosé Salvador Núñez CuevasNo ratings yet

- Step Wise Chair Side MillingDocument6 pagesStep Wise Chair Side MillingPavithra balasubramaniNo ratings yet

- Important Application of Tooth Anatomy in Dental PracticeDocument36 pagesImportant Application of Tooth Anatomy in Dental PracticemirfanulhaqNo ratings yet

- 2009 Samet Classification Prognosis Evaluation Individual Teeth Comprehensive ApproachDocument12 pages2009 Samet Classification Prognosis Evaluation Individual Teeth Comprehensive ApproachFabian SanabriaNo ratings yet

- Thực tập chẩn đoán hình ảnhDocument90 pagesThực tập chẩn đoán hình ảnhPhat NgoNo ratings yet

- Three-Dimensional Cone Beam Computed Tomography Analysis of Temporomandibular Joint Response To The Twin-Block Functional ApplianceDocument12 pagesThree-Dimensional Cone Beam Computed Tomography Analysis of Temporomandibular Joint Response To The Twin-Block Functional AppliancealejandroNo ratings yet

- CLCPDocument43 pagesCLCPeviltohuntNo ratings yet

- Dental Chair: Patient PositionsDocument2 pagesDental Chair: Patient PositionsBatool ZahraNo ratings yet

- Bishara Soft Tissue Grafting PDFDocument7 pagesBishara Soft Tissue Grafting PDFMark BisharaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Probo Kak Risna - Id.enDocument14 pagesJurnal Probo Kak Risna - Id.enaccangNo ratings yet

- Ivo ClarDocument34 pagesIvo ClarTissa RahadiantiNo ratings yet

- Occlusal Splint InstructionsDocument3 pagesOcclusal Splint InstructionsTj MusiczNo ratings yet

- Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion - Jeffrey P. Okeson - 8th Edition (2019) 512 PP., ISBN: 9780323582100-101-114Document14 pagesManagement of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion - Jeffrey P. Okeson - 8th Edition (2019) 512 PP., ISBN: 9780323582100-101-114Habeeb HatemNo ratings yet

- Uae Specialist Prometric Exam (Moh Dha Haad) For ProsthontistsDocument1 pageUae Specialist Prometric Exam (Moh Dha Haad) For ProsthontistsStephen PanneerNo ratings yet

- Sheiham 2015Document7 pagesSheiham 2015Cristiane Costa SilvaNo ratings yet