Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Same 7

Same 7

Uploaded by

elnadi.grafistOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Same 7

Same 7

Uploaded by

elnadi.grafistCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA | Original Investigation

Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal

Complications Among Women With Gestational Diabetes

A Randomized Clinical Trial

Marie-Victoire Sénat, MD, PhD; Helene Affres, MD; Alexandra Letourneau, MD; Magali Coustols-Valat, MD; Marie Cazaubiel, MD; Helene Legardeur, MD;

Julie Fort Jacquier, MSc; Nathalie Bourcigaux, MD; Emmanuel Simon, MD; Anne Rod, MD; Isabelle Héron, MD; Virginie Castera, MD;

Loic Sentilhes, MD, PhD; Florence Bretelle, MD, PhD; Catherine Rolland, MD; Mathieu Morin, MSc; Philippe Deruelle, MD, PhD; Celine De Carne, MD;

François Maillot, MD, PhD; Gael Beucher, MD; Eric Verspyck, MD, PhD; Raoul Desbriere, MD; Sandrine Laboureau, MD; Delphine Mitanchez, MD, PhD;

Jean Bouyer, PhD; for the Groupe de Recherche en Obstétrique et Gynécologie (GROG)

Editorial page 1769

IMPORTANCE Randomized trials have not focused on neonatal complications of glyburide Supplemental content

for women with gestational diabetes.

OBJECTIVE To compare oral glyburide vs subcutaneous insulin in prevention of perinatal

complications in newborns of women with gestational diabetes.

DESIGN, SETTINGS, AND PARTICIPANTS The Insulin Daonil trial (INDAO), a multicenter

noninferiority randomized trial conducted between May 2012 and November 2016

(end of participant follow-up) in 13 tertiary care university hospitals in France including

914 women with singleton pregnancies and gestational diabetes diagnosed between

24 and 34 weeks of gestation.

INTERVENTIONS Women who required pharmacologic treatment after 10 days of dietary

intervention were randomly assigned to receive glyburide (n=460) or insulin (n=454).

The starting dosage for glyburide was 2.5 mg orally once per day and could be increased if

necessary 4 days later by 2.5 mg and thereafter by 5 mg every 4 days in 2 morning and

evening doses, up to a maximum of 20 mg/d. The starting dosage for insulin was 4 IU to 20 IU

given subcutaneously 1 to 4 times per day as necessary and increased according to

self-measured blood glucose concentrations.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary outcome was a composite criterion including

macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and hyperbilirubinemia. The noninferiority margin

was set at 7% based on a 1-sided 97.5% confidence interval.

RESULTS Among the 914 patients who were randomized (mean age, 32.8 [SD, 5.2] years),

98% completed the trial. In a per-protocol analysis, 367 and 442 women and their neonates

were analyzed in the glyburide and insulin groups, respectively. The frequency of the primary

outcome was 27.6% in the glyburide group and 23.4% in the insulin group, a difference of

4.2% (1-sided 97.5% CI, −⬁ to 10.5%; P=.19).

CONCLUSION AND RELEVANCE This study of women with gestational diabetes failed to show

that use of glyburide compared with subcutaneous insulin does not result in a greater

frequency of perinatal complications. These findings do not justify the use of glyburide

as a first-line treatment. Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01731431

Group Information: Members of

GROG are listed at the end of this

article.

Corresponding Author:

Marie-Victoire Sénat, MD, PhD,

Service Gynécologie Obstétrique,

Hôpital Bicêtre, 78 avenue du

Général Leclerc, 94270 Le Kremlin

Bicêtre, France (marie-victoire.senat

JAMA. 2018;319(17):1773-1780. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.4072 @aphp.fr).

(Reprinted) 1773

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Research Original Investigation Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes

G

estational diabetes is a major public health concern, and

its rate is increasing worldwide.1,2 Adequate treat- Key Points

ment of women with gestational diabetes reduces fetal

Question Does use of glyburide compared with subcutaneous

and maternal morbidity.3 Insulin continues to be the American insulin result in an increase in perinatal complications among

Diabetes Association–recommended first-line therapy and the women with gestational diabetes?

only pharmacologic treatment approved by the US Food and

Findings In this noninferiority randomized trial that included 914

Drug Administration.4 The American College of Obstetri-

pregnant women with gestational diabetes, the rate of the

cians and Gynecologists recommends not using glyburide as composite criterion (including macrosomia, neonatal

a first-choice pharmacologic treatment.5 However, insulin is hypoglycemia, and hyperbilirubinemia) was 27.6% with glyburide

expensive and inconvenient because it requires several sub- and 23.4% with insulin; the upper confidence limit of the

cutaneous injections a day and careful management of dose difference was 10.5%, which exceeded the prespecified

adaptation.6 Glyburide is a potential alternative treatment noninferiority margin of 7%.

and, as an oral drug, is more acceptable to patients. Since the Meaning These findings do not support noninferiority of glyburide

first randomized trial by Langer et al7 showed that glycemic for prevention of perinatal complications of gestational diabetes.

control is similar for the 2 treatments, glyburide has become

a common additional pharmacotherapy for gestational dia- Exclusion criteria were diabetes, fasting blood glucose

betes in the United States,2 while in Europe it is not used concentration greater than 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L), glucose

routinely. Meta-analyses8-13 and recent studies14,15 question screening test performed before 24 weeks of gestation, mul-

use of glyburide, reporting an increased rate of neonatal tiple pregnancy, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, and

morbidities compared with insulin, especially macrosomia known liver or renal disease.

and hypoglycemia. However, because all randomized trials Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes were given in-

comparing glyburide with insulin used maternal glycemic dividual nutrition education by a dietitian designed to pro-

control as the primary outcome, they were not optimally vide 25 kcal/kg per day for overweight and obese women and

designed to investigate neonatal complications.7,8 The aim 35 kcal/kg per day for women at normal weight. Nutritional in-

of the present study was therefore to compare glyburide take was divided into 3 meals and 2 snacks daily. Women were

and insulin for prevention of perinatal complications, espe- taught to self-monitor capillary blood glucose levels 4 times

cially because the American College of Obstetricians and daily (fasting and 2 hours after each meal). Glycemic goals were

Gynecologists recommends equivalence or noninferiority considered not achieved after 10 days of well-managed diet

trials comparing oral agents with insulin.5 The comparison if at least 2 blood glucose values above the targets were ob-

was planned as a noninferiority test because glyburide is an served over a week (fasting: ≥95 mg/dL; 2-hour postprandial:

oral pharmacotherapy for gestational diabetes and is more ≥120 mg/dL), with no variations in diet. Women who did not

convenient for patients, with greater ease of administration meet glycemic goals were eligible for randomization to 1 of the

and reduced costs. 2 treatment groups.

Randomization

Eligible women were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to

Methods

receive glyburide or insulin. An independent, centralized,

Study Design and Patients computer-generated randomization sequence (CleanWeb,

We performed a multicenter randomized noninferiority trial Tele-medicine Technologies) was used for this allocation

(the Insulin Daonil trial [INDAO]) in 13 tertiary care univer- according to a permuted-block method with block sizes ran-

sity hospitals in France. Recruitment lasted from May 2012 domly chosen from 2 to 8, stratified by center. Clinicians

to September 2016, and November 2016 was the end of and participants had no access to the list but could not be

patient follow-up. The trial protocol is available in Supplement blinded to group allocation after randomization.

1 and the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 2. All

patients provided written informed consent before enroll- Procedures

ment. The trial protocol was approved by the ethics commit- For glyburide, the starting dosage for therapy was 2.5 mg

tee of the Poissy St-Germain Hospital. An independent data orally once per day and could be increased if necessary 4

and safety monitoring committee periodically reviewed days later by 2.5 mg and thereafter by 5 mg every 4 days in

study outcomes. 2 doses, morning and evening, up to a maximum of 20 mg/d.

Women with a singleton pregnancy who were diag- If the maximum tolerated dosage was reached without

nosed as having gestational diabetes between 24 and 34 achieving the desired glucose values of less than 95 mg/dL

weeks of gestation were eligible. Gestational diabetes was (5.3 mmol/L) for fasting measurements and less than

diagnosed if a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test resulted in 120 mg/dL (6.7 mmol/L) for 2-hour postprandial measure-

1 or more abnormal blood glucose values: greater than ments, treatment was switched to insulin.

92 mg/dL (5.1 mmol/L), greater than 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L), For insulin, the starting dosage for rapid analogs was 4 IU

or greater than 153 mg/dL (8.5 mmol/L) for fasting, 1-hour given subcutaneously before meals, 1 to 3 times per day as nec-

postprandial, or 2-hour postprandial blood glucose concen- essary and increased by 2 IU every 2 days according to the post-

tration, respectively.16 prandial blood glucose value. If necessary, the starting dosage

1774 JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 (Reprinted) jama.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes Original Investigation Research

for basal or intermediate insulin was 4 IU to 8 IU given subcu-

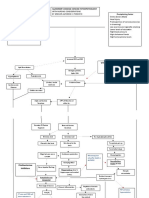

Figure. Participant Flow in the Insulin Daonil Trial

taneously at bedtime and increased by 2 IU every 2 days ac-

cording to the morning fasting blood glucose value. Women

were taught to self-adjust their insulin doses in an effort to 914 Pregnant women with gestational

diabetes randomizeda

reach and maintain glycemic goals throughout pregnancy.

All women had a clinical assessment with a visit to an en-

docrinologist at days 8 and 21 after randomization and then ev- 460 Randomized to receive glyburide 454 Randomized to receive insulin

ery 15 days to once per month according to level of glycemic con- 450 Received glyburide treatment 444 Received insulin treatment

as randomized as randomized

trol. In addition to these planned visits, women received prenatal 10 Did not receive treatment 10 Did not receive treatment

care at their institutions as deemed appropriate by their care- as randomized as randomized

3 Gestational diabetes 7 Pharmacotherapy

givers (eg, general physicians, obstetricians, midwives). New- diagnosed >24 wk of unnecessary

born monitoring was identical to the usual recommendation for gestation 1 Multiple pregnancy

2 Pharmacotherapy 1 Chronic hypertension

newborns of mothers with diabetes, with early and frequent unnecessary 1 Refused treatment

breast or bottle feeding: from birth, at 30 minutes and then ev- 1 Fasting blood glucose

level >126 mg/dL

ery 2 or 3 hours. Neonatal glucose monitoring started immedi- 1 Type 1 diabetes

ately after birth and included frequent measurements (8 in the 1 Included in another

randomized trial

first 24 hours and 2 on day 2). The number of glucose measure- 1 Withdrew consent

ments was increased when clinically required. 1 Refused treatment

Outcome Variables 81 Switched to insulin treatment

The primary outcome was a composite criterion of perinatal

complications associated with gestational diabetes, includ- 367 Had data for primary outcome 442 Had data for primary outcome

2 No data for primary outcome 2 No data for primary outcome

ing macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and hyperbilirubi- (missing data) 1 Stillbirth

nemia. Macrosomia was defined as birth weight greater than 1 Medical termination of

pregnancy

4000 g or above the 90th percentile for gestational age ac-

cording to French curves.17 Neonatal hypoglycemia was de-

367 Included in per-protocol analysis 442 Included in per-protocol analysis

fined as blood glucose value less than 36 mg/dL (2 mmol/L)

after 2 hours of life.18 Hyperbilirubinemia was defined as the a

Data on women who were screened for eligibility and reasons why some of

need for phototherapy without another cause of jaundice. them were not randomized were not recorded and are not shown.

The prespecified secondary outcomes included (1) neo-

natal outcomes of perinatal death, admission to a neonatal in-

tensive care unit (NICU) and neonatal ward, respiratory dis-

tress syndrome, birth injury, ponderal index (calculated as the newborn (birth weight, Apgar score, severity of hypogly-

[birth weight in grams divided by height in centimeters cubed] cemia), reasons for admission to the NICU, mean insulin or gly-

times 100), pH level of less than 7, lactates in 3 categories buride dosages received by women, and severe episodes of ma-

(<6 mmol/L, 6-9 mmol/L, and >9 mmol/L), and base excess ternal hypoglycemia (defined as glucose level <40 mg/dL).

(not recorded); (2) maternal outcomes of glycemic control dur-

ing pregnancy (see below), hypoglycemia (defined as blood Sample Size

glucose level <60 mg/dL [3.3 mmol/L]) and/or a symptomatic We estimated the usual frequency of the primary outcome

episode of hypoglycemia with clinical symptoms of severity (macrosomia, hypoglycemia, and hyperbilirubinemia) in new-

(confusion, poor coordination, double vision, convulsion, or borns of women with gestational diabetes treated with insu-

inability to self-treat symptoms), premature delivery, mode of lin to be 18% based on published randomized trials compar-

delivery, perineal trauma, percentage switch from glyburide ing insulin vs either usual prenatal care 3,19 or glyburide

to insulin, and maternal satisfaction; and (3) other outcomes, treatment7,20-23 and based on (unpublished) retrospective data

data for which are not presented here, including number of pre- from the participating centers. The noninferiority boundary

natal visits, number of diabetologist visits, and hospitaliza- was based on clinical evidence.24 We asked a group of clini-

tion days during pregnancy. cians to consider what increase in neonatal complications they

Glycemic control during pregnancy was quantified for each would accept in exchange for the potential benefits offered by

woman by the percentage of blood glucose measurements at glyburide.25 They estimated that a 25% rate of perinatal com-

95 mg/dL or greater for fasting measurements and 120 mg/dL plications in the glyburide group was acceptable. Glyburide was

or greater for 2-hour postprandial measurements. Three cat- then considered noninferior to insulin if the upper confi-

egories were defined (separately for fasting and postprandial dence limit of the difference did not exceed the prespecified

measurements): good glycemic control (<20%), moderate or noninferiority margin of 7%. With these assumptions and with

fairly good glycemic control (20%-40%), and poor glycemic con- a statistical power of 80%, a type I error of 5%, and a 2-sided

trol (>40%). A satisfaction questionnaire was given to women test, 372 women per group were required. With anticipation

in the first postpartum week to assess treatment acceptability. that approximately 20% of patients in the glyburide group

Additional outcomes considered exploratory were com- would be switched to the insulin group,26 450 women per

ponents of the primary composite outcome, characteristics of group were necessary.

jama.com (Reprinted) JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 1775

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Research Original Investigation Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes

from glyburide to insulin treatment comparing the differ-

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Women Included in the Primary

Per-Protocol Analysis ence (glyburide rate − insulin rate) in the frequency of the pri-

mary outcome.27

Glyburide Group Insulin Group

Characteristics (n = 367) (n = 442) Noninferiority of glyburide compared with insulin was

Age, mean (SD), y 32.5 (5.1) 32.6 (5.3) demonstrated if the upper bound of the 1-sided 97.5% confi-

Multiparity, No. (%) 216 (58.9) 293 (66.3) dence interval of this difference was smaller than the prespeci-

Prepregnancy BMI, 27.3 (5.5) 27.8 (5.8) fied threshold of 7%.

mean (SD)a A prespecified sensitivity analysis for women who

BMI at diagnosis, 30.7(5.1) 31.1(5.4) switched treatment was performed on the intention-to-treat

mean (SD)a

Geographical origin,

population. A complementary prespecified analysis was per-

No. (%) formed by adjusting for baseline characteristics that differed

Europe 146 (41.3) 184 (43.2) between randomized groups.

North Africa 124 (34.9) 136 (31.9)

Sub-Saharan Africa 35 (9.9) 50 (11.7) Secondary Outcomes

Asia 19 (5.4) 21 (4.9) Analyses of secondary outcomes and post hoc analyses were

Other 31 (8.7) 35 (8.2) made with superiority tests and 95% CIs for differences and

Previous gestational 73 (20.0) 88 (19.9) should be considered exploratory because no correction for

diabetes, No. (%) multiple comparisons was done.

Gestational age, No imputation was made for missing data because there

median (IQR), wk+d

At OGTT screening 26+5 (25+3 to 28+0) 26+3 (25+1 to 28+0)

were only 2 missing data for the primary outcome and very

few for secondary outcomes. Complete case analyses were

At treatment 32+6 (30+6 to 34+3) 32+3 (30+3 to 34+1)

done. The threshold for statistical significance was set at

Type of blood glucose

measurement with P<.05 with a 2-sided test; for the primary outcome, a 1-sided

abnormal result 97.5% confidence interval was considered. Statistical analy-

at randomization,

No. (%) ses were performed using Stata software, release 14.28

Only fasting 12 (3.3) 13 (2.9)

Only 2-h postprandial 65 (17.7) 72 (16.3)

Both fasting 290 (79.0) 357 (80.8)

and 2-h postprandial Results

Proportion of abnormal

blood glucose results Characteristics of the Women

at randomization, Among 914 women with gestational diabetes (mean age,

median (IQR)b

32.8 [SD, 5.2] years), 460 were randomized to receive gly-

Fasting blood glucose 0.3 (0.1-0.6) 0.3 (0.1-0.5)

≥95 mg/dL buride treatment and 454 to receive insulin treatment. After

Postprandial blood 0.2 (0.1-0.3) 0.2 (0.1-0.3) randomization, 18 patients (2.0%) were excluded from the

glucose ≥120 mg/dL analysis because they did not meet the inclusion criteria and

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test. 6 because they had no data for the primary outcome or re-

a

Body mass index (BMI) is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in fused the treatment (Figure). Among the 448 women remain-

meters squared. ing in the glyburide group, 81 (18%) were switched to insulin,

b

For each woman, the number of abnormal blood glucose assay results over all most often before reaching the maximum glyburide dosage.

of her blood glucose assays between inclusion and randomization was

computed, then medians and IQRs of these proportions were calculated. The per-protocol analysis therefore included 809 women and

their neonates, 367 in the glyburide group and 442 in the in-

sulin group (Figure).

The baseline characteristics of the 809 included women

Statistical Analysis are shown in Table 1. Overall, there were no noticeable

Continuous variables were summarized as means and stan- between-group differences in demographic variables or

dard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges if non– blood glucose values at inclusion. Multiparity was more fre-

normally distributed and qualitative variables as numbers and quent in the insulin group (66.3% vs 58.9%), and gestational

percentages of participants. To take into account that the trial age at treatment was slightly greater in the glyburide group.

was multicenter, mixed-effects models were used to com-

pare the 2 groups (logistic for qualitative variables and linear Primary Outcome

for quantitative variables). These models were used to esti- The frequency of the primary outcome was 27.6% in the

mate means and standard deviations or percentages in each glyburide group and 23.4% in the insulin group (differ-

group and differences in means or percentages and 95% con- ence, 4.2%; 1-sided 97.5% CI, −⬁ to 10.5%; P = .19), and the

fidence intervals between groups. upper confidence limit exceeded the noninferiority mar-

gin of 7% (Table 2). When adjusted for multiparity and gesta-

Primary Outcome tional age at treatment, the results remained similar (differ-

The analysis of the primary outcome was performed on the ence, 4.4%; 1-sided 97.5% CI, −⬁ to 10.5%; P = .20) (eFigure in

per-protocol population excluding women who were switched Supplement 3).

1776 JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 (Reprinted) jama.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes Original Investigation Research

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Per-Protocol Outcomes Analyses

Glyburide Group Insulin Group Difference, %

Outcomes (n = 367) (n = 442) (95% CI) P Valuea

Primary Outcome

Neonatal composite criterion, 101 (27.6) 103 (23.4) 4.2 (−⬁ to 10.5)c .19d

No. (%)b

Neonatal Secondary Outcomes

Admission to neonatal intensive 10 (2.3) 11 (2.4) 0.02 (−2.4 to 2.7) .87

care unit before 48 h of life, No. (%)

Admission to neonatal ward, 27 (7.9) 34 (8.2) −0.3 (−5.2 to 4.6) .86

No. (%)e

Severe respiratory distress 8 (1.9) 11 (2.2) −0.3 (−2.7 to 2.0) .75

syndrome, No (%) a

P value of the test of the coefficient

Birth injury, No. (%) 6 (1.5) 9 (1.9) −0.4 (−2.3 to 1.5) .66 of the mixed-effects model used to

Shoulder dystocia, No. 1 2 account for multiple centers

(logistic for qualitative variables,

Bone fracture, No. 1 6 linear for quantitative ones).

Nerve palsy, No. 1 0 b

Macrosomia, neonatal

Other, No.f 3 1 hypoglycemia, and

Ponderal index, mean (SD)g 2.75 (0.04) 2.74 (0.04) 0.01 (−0.08 to 0.10) .52 hyperbilirubinemia.

c

Confidence interval for the primary

pH <7, No. (%) 2 (0.6) 2 (0.5) 0.0 (−1.0 to 1.2) .88

outcome is a 1-sided 97.5%

h

Lactates, mmol/L, No. (%) confidence interval.

<6 175 (79.2) 219 (82.3) −3.1 (−10.2 to 3.9) d

P value of the noninferiority test.

6-9 33 (14.9) 41 (15.4) −0.5 (−6.9 to 5.9) .14 e

Less sick newborns are hospitalized

>9 13 (5.9) 6 (2.3) 3.6 (0.05 to 7.2) in this unit; more severely ill

newborns are in the neonatal

Maternal Secondary Outcomes

intensive care unit.

Glycemic control f

Glyburide group: facial hematoma,

during pregnancyi

serosanguine hump, scalp wound;

Fasting blood glucose insulin group: serosanguine hump.

≥95 mg/dL, No. (%)

g

Good (<20%) 248 (71.7) 264 (63.2) 8.5 (1.9 to 15.2) Ponderal index (calculated as [birth

weight in grams divided by height in

Moderate or fair (20%-40%) 68 (19.7) 83 (19.9) −0.2 (−5.9 to 5.5) .003 centimeters cubed] times 100) may

Poor (>40%) 30 (8.7) 71 (17.0) −8.3 (−13.0 to −3.7) increase when quality maternal

Postprandial blood glucose glycemic control decreases. The

≥120 mg/dL, No. (%) usual 10th, 50th, and 90th

percentiles of the ponderal index

Good (<20%) 200 (57.8) 206 (49.3) 8.5 (1.5 to 15.6)

are 2.2, 2.6, and 3.1.

Moderate or fair (20%-40%) 109 (31.5) 165 (39.5) −8.0 (−14.8 to −1.2) .051 h

Lactate levels were known for 60%

Poor (>40%) 37 (10.7) 47 (11.2) −0.5 (−5.0 to 3.9) of newborns in both groups.

Maternal hypoglycemia, No. (%)j 93 (28.8) 13 (3.5) 25.3 (16.6 to 34.0) <.001 i

Percentage of measurements at or

Preterm delivery, No. (%) 25 (6.8) 18 (4.1) 2.7 (−1.0 to 6.4) .09 above the blood glucose thresholds

of 95 mg/dL for fasting

Mode of delivery, No. (%)

measurements and 120 mg/dL for

Spontaneous vaginal 205 (55.9) 251 (56.8) −0.9 (−7.8 to 5.9) 2-hour postprandial measurements.

Assisted vaginal 63 (17.2) 67 (15.2) 2.0 (−3.1 to 7.1) Three categories were defined:

.08 good glycemic control (<20% of

Elective cesarean 36 (9.8) 66 (14.9) −5.1 (−9.6 to −0.6)

measurements meeting threshold),

Emergency cesarean 63 (17.2) 58 (13.1) 4.0 (−0.9 to 9.0) moderate or fairly good glycemic

Any perineal trauma 3 (0.8) 1 (0.2) 0.6 (−0.8 to 2.0) .27 control (20%-40%), and poor

glycemic control (>40%). Data were

Maternal satisfaction:

preferred treatment missing for 21 in the glyburide group

for a future pregnancy, No. (%)k and 24 in the insulin group.

j

Glyburide 207 (78.7) 125 (43.6) 35.2 (27.6 to 42.7) At least 1 fasting or postprandial

blood glucose measurement <60

Insulin 7 (2.7) 57 (19.9) −17.2 (−22.2 to −12.2) <.001

mg/dL during pregnancy.

Unknown 49 (18.6) 105 (36.6) −18.0 (−25.3 to −10.7) k

There were 554 responses (68.5%).

Intention-to-treat sensitivity analysis indicated a differ- an infant weighing 3400 g; 1 medical termination of preg-

ence of 4.2% (1-sided 97.5% CI, −⬁ to 10.0%; P = .17) (eTable 1 nancy performed at 36 weeks of gestation because of severe

in Supplement 3). brain abnormalities).

The rates of admission to an NICU and neonatal nursery

Prespecified Secondary Neonatal Outcomes did not differ significantly in the 2 groups. There were no sig-

No perinatal deaths occurred in the glyburide group, and nificant between-group differences in birth injury, ponderal

there were 2 in the insulin group (1 patient with unexplained index, pH level of less than 7, lactate levels, and respiratory

intrauterine death at 40 weeks of gestation with birth of distress syndrome (Table 2).

jama.com (Reprinted) JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 1777

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Research Original Investigation Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes

Table 3. Post Hoc Per-Protocol Outcomes Analyses

Glyburide Group Insulin Group Difference, %

Outcomes (n = 367) (n = 442) (95% CI) P Valuea

Composite Criterion Components

Macrosomia, No. (%) 59 (16.2) 65 (14.8) 1.4 (−3.9 to 6.6) .59

Hypoglycemia, No. (%) 45 (12.2) 32 (7.2) 5.0 (0.5 to 9.5) .02

Hyperbilirubinemia, No. (%) 14 (3.8) 14 (3.1) 0.6 (−2.0 to 3.3) .61

Neonatal Outcomes

Birth weight, mean (SD), g 3341 (513) 3331 (476) 10 (−58 to 78) .77

a

Birth weight >4000 g, No. (%) 33 (9.3) 28 (6.6) 2.7 (−1.9 to 7.4) .16 P value of the test of the coefficient

Apgar score ≤7 at 5 min, No. (%) 3 (0.8) 11 (2.5) −1.7 (−3.4 to 0.04) .08 of the mixed-effects model used to

account for multiple centers

Reason for admission to neonatal (logistic for qualitative variables,

intensive care unit before 48 h of life, No.

linear for quantitative ones).

Severe respiratory distress syndrome 8 11 b

One malformation and 1

Otherb 2 0 maternal/fetal infection.

Maternal Outcomes c

Mean dosages were calculated from

Insulin dosage received, mean (SD), units/dc 19.6 (14.6) diagnosis to delivery.

d

Glyburide dosage received, mean (SD), mg/dc 5.4 (3.4) At least 1 fasting or postprandial

d blood glucose measurement

Maternal hypoglycemia, No. (%) 13 (3.8) 4 (1.0) 2.8 (0.2 to 5.5) .02

<40 mg/dL during pregnancy.

Prespecified Secondary Maternal Outcomes 1 mmol/L or lower among 2 newborns in the glyburide group

Blood glucose control was significantly better during preg- and 3 newborns in the insulin group. No neonate presented

nancy in the glyburide group, with 71.7% of women main- with severe clinical signs of hypoglycemia. Among newborns

taining good fasting glycemic control compared with 63.2% admitted to the NICU, none were admitted because of clinical

in the insulin group (difference, 8.5%; 95% CI, 1.9%-15.2%; signs of hypoglycemia or for treatment of hypoglycemia.

P = .003) (Table 2). Good control of postprandial glucose was More women in the glyburide group had a severe hypo-

achieved in 57.8% of women in the glyburide group and glycemia episode (blood glucose level <40 mg/dL: 13 [3.8%]

49.3% in the insulin group (difference, 8.5%; 95% CI, 1.5%- in the glyburide group vs 4 [1.0%] in the insulin group; differ-

15.6%; P = .051). ence, 2.8%; 95% CI, 0.2%-5.5%; P = .02). Among them,

More women in the glyburide group had at least 1 epi- 2 women in the glyburide group and 1 woman in the insulin

sode of fasting or postprandial glycemia (blood glucose group reported symptoms with an inability to self-treat

<60 mg/dL) during pregnancy (glyburide group, 93 [28.8%] their symptoms.

vs insulin group, 13 [3.5%]; difference, 25.3%; 95% CI, 16.6%-

34.0%; P < .001). There were no significant between-group

differences in mode of delivery, preterm delivery, and peri-

neal trauma. Overall, 68.5% of women completed the satis-

Discussion

faction questionnaire during their maternity stay. There was This study of women with gestational diabetes failed to show

no significant relationship between nonresponse and the that use of glyburide compared with subcutaneous insulin

composite criterion (P = .82). In terms of maternal satisfac- does not result in a greater frequency of perinatal complica-

tion, 23.6% of patients in the insulin group indicated that tions. These findings do not justify use of glyburide as a first-

therapy is the most difficult part of the treatment, whereas line treatment.

only 5% did in the glyburide group (P < .001). Among women The higher rate of the primary outcome in the glyburide

treated with glyburide, 78.7% indicated that they would group was mainly due to an increased rate of neonatal hypo-

choose glyburide treatment in a subsequent pregnancy, glycemia. This is consistent with results of meta-analyses

whereas only 19.9% of women treated with insulin would including observational studies and randomized trials.8-13

choose insulin again (P < .001) (Table 2). However, most of these meta-analyses also mention a signifi-

cantly increased risk of macrosomia 8,9,11 in neonates of

Post Hoc Analyses women treated with glyburide, and 2 studies using large

Per-protocol analysis results for the components of the com- administrative databases have additionally reported an

posite criterion are given in Table 3 (and in eTable 2 in increased risk of respiratory distress syndrome and NICU

Supplement 3 for the intention-to-treat analysis). Hypoglyce- admissions with glyburide.14,15 These findings are not consis-

mia occurred in 12.2% of the glyburide group and in 7.2% of tent with the results, albeit exploratory, reported in Table 3,

the insulin group (difference, 5%; 95% CI, 0.5%-9.5%; P = .02). because no significant between-group differences were

There were no significant between-group differences in mac- found in the rates of macrosomia, hyperbilirubinemia,

rosomia and hyperbilirubinemia rates. admission to the NICU or neonatal nursery, or respiratory dis-

Severity of hypoglycemia among newborns did not differ tress syndrome. An isolated increase in neonatal hypoglyce-

significantly between the groups, with blood glucose levels of mia in the glyburide group is in agreement with data from the

1778 JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 (Reprinted) jama.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes Original Investigation Research

latest meta-analysis comparing management of gestational the primary outcome or the reason for admission to the NICU,

diabetes with glyburide vs insulin.12 The rate of neonatal and these must therefore be considered as exploratory or post

hypoglycemia in the glyburide group was 12.2%, which is of hoc analyses and are of reduced weight. Second, criteria cho-

the same magnitude as the 9% reported by Langer et al7 in sen to assess satisfaction in terms of women’s treatment pref-

their insulin group but much lower than the 33% reported by erences for a future pregnancy may be questioned, inasmuch

Bertini et al21 and the 25% reported by Silva et al23 in their as each woman received only 1 of the 2 treatments and had no

glyburide groups. A prospective cohort study involving neo- experiential basis for making such a comparison.

nates considered to be at risk of hypoglycemia, including The noninferiority framework provides, on one hand, a bi-

40% of neonates born to a mother with diabetes, showed nary conclusion (significant or not) and, on the other hand, a

that with an on-treatment blood glucose level threshold of more quantitative result with the boundaries of the 95% con-

47 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), neonatal hypoglycemia was not asso- fidence interval.30

ciated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years Although the data do not allow a conclusion that gly-

compared with neonates with normal glucose levels.29 buride is not inferior to insulin in the prevention of perinatal

Because women had gestational diabetes, study physi- complications, the results suggest that the increase in com-

cians knew the infants were at risk of hypoglycemia, and neo- plications may be no more than 10.5% compared with insu-

natal glucose was monitored frequently after birth, so it is un- lin. This result should be balanced with the ease of use and bet-

likely that there were neonates with unrecognized and ter satisfaction with glyburide. In clinical situations in which

untreated hypoglycemia. The 18% glyburide-to-insulin switch an oral agent may be necessary, mothers, informed by their

rate is consistent with literature reports.26 physicians, would be appropriate decision makers based on

The strengths of the present study include that it was a mul- their own weighing of benefits and risks.

ticenter study, which increases its generalizability. In addi-

tion, a neonatal criterion was chosen as the primary outcome

because, to our knowledge, no previous randomized trials have

optimally assessed the potential effect of glyburide on pre-

Conclusions

vention of perinatal complications.7,20-23 This study of women with gestational diabetes failed to show

that use of glyburide compared with subcutaneous insulin does

Limitations not result in a greater frequency of perinatal complications.

This study had several limitations. First, some criteria were not These findings do not justify the use of glyburide as a first-

prespecified in the initial protocol, such as the components of line treatment.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Department of Endocrinology, Rouen University Neonatology, Armand Trousseau Hospital, Paris,

Accepted for Publication: March 16, 2018. Hospital–Charles Nicolle, Rouen, France (Héron); France (Mitanchez).

Department of Endocrinology, St Joseph Hospital, Author Contributions: Dr Sénat had full access to

Author Affiliations: Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux Marseille, France (Castera); Department of

de Paris, Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, all of the data in the study and takes responsibility

Obstetrics and Gynecology, Angers University for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the

Bicêtre Hospital, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France Hospital, Angers, France (Sentilhes); Department of

(Sénat); University of Paris-Sud, University of data analysis.

Obstetrics and Gynecology, Bordeaux University Concept and design: Sénat, Bouyer.

Medicine Paris-Saclay, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France Hospital, Bordeaux, France (Sentilhes); Assistance

(Sénat); Centre for Research in Epidemiology and Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data:

Publique–Hôpitaux de Marseille; AMU, Aix-Marseille Sénat, Affres, Letourneau, Coustols-Valat,

Population Health, Université Paris-Saclay, Université, Department of Gynecology and

Université Paris-Sud, Université de Versailles Cazaubiel, Legardeur, Fort-Jacquier, Bourcigaux,

Obstetrics, Pole Femme Enfant, Marseille, France Simon, Rod, Héron, Castera, Sentilhes, Bretelle,

Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, INSERM, Villejuif, France (Bretelle); Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris,

(Sénat, Bouyer); Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Rolland, Morin, De Carne, Maillot, Beucher,

Department of Hepato-Enterology-Gastroenteritis, Verspyck, Desbriere, Laboureau, Bouyer.

Paris, Department of Reproductive Endocrinology, Béclère Hospital, Clamart, France (Rolland);

Bicêtre Hospital, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France Drafting of the manuscript: Sénat, Affres, Fort-

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Toulouse Jacquier, Bourcigaux, Castera, Bretelle, Morin,

(Affres); Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, University Hospital, Toulouse, France (Morin);

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Béclère Beucher, Desbriere, Bouyer.

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Lille Critical revision of the manuscript for important

Hospital, Clamart, France (Letourneau); University, EA 4489–Environnement Périnatal et

Department of Endocrinology-Obstetrics, Toulouse intellectual content: Sénat, Affres, Letourneau,

Santé, Lille, France (Deruelle); Assistance Publique– Coustols-Valat, Cazaubiel, Legardeur, Simon, Rod,

University Hospital, Toulouse, France Hôpitaux de Paris, Department of Gynecology-

(Coustols-Valat); Department of Endocrinology, Héron, Sentilhes, Rolland, De Carne, Maillot,

Obstetrics, Trousseau Hospital, Paris, France Verspyck, Laboureau, Bouyer.

Lille University Hospital EA 4489–Environnement (De Carne); Department of Internal Medicine,

Périnatal et Santé, Lille, France (Cazaubiel); Statistical analysis: Bouyer.

François-Rabelais University, University Hospital Obtained funding: Sénat, Coustols-Valat, Bouyer.

Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Center of Tours, Tours, France (Maillot);

Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hôpital Administrative, technical, or material support:

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Caen Sénat, Coustols-Valat, Fort-Jacquier, Bourcigaux,

Louis Mourier, Colombes, France (Legardeur); University Hospital, Caen, France, France

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Poissy Morin, Desbriere.

(Beucher); Department of Gynecology and Supervision: Sénat, Affres, Legardeur.

St-Germain Hospital, Poissy, France (Jacquier); Obstetrics, Rouen University Hospital–Charles

Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Nicolle, Rouen, France (Verspyck); Department of Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have

Department of Endocrinology, St Antoine Hospital Gynecology-Obstetrics, St Joseph Hospital, completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for

Paris, France (Bourcigaux); Department of Marseille, France (Desbriere); Department of Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Obstetrics, Gynecology and Fetal Medicine, Endocrinology, Angers University Hospital, Angers, Dr Sentilhes reports consultancy work and lecturing

University Hospital Center of Tours, Tours, France France (Laboureau); Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux for Ferring Laboratories. No other disclosures

(Simon); Department of Endocrinology, Caen de Paris, Sorbonne Universities, University Pierre were reported.

University Hospital, Caen, France, France (Rod); and Marie Curie, University Paris 06, Department of

jama.com (Reprinted) JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 1779

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

Research Original Investigation Effect of Glyburide vs Subcutaneous Insulin on Perinatal Complications in Gestational Diabetes

Group Information: Participating members/ REFERENCES mellitus: glyburide compared to subcutaneous

collaborators of the Groupe de Recherche en 1. Farrar D. Hyperglycemia in pregnancy: insulin therapy and associated perinatal outcomes.

Obstétrique et Gynécologie (GROG): Thomas prevalence, impact, and management challenges. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(4):379-384.

Schmitz, MD, PhD, Department of Gynecology- Int J Womens Health. 2016;8:519-527. 16. Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al;

Obstetrics, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, International Association of Diabetes and

Robert Debré, GROG president; Elie Azria, MD, PhD, 2. Camelo Castillo W, Boggess K, Stürmer T,

Brookhart MA, Benjamin DK Jr, Jonsson Funk M. Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel.

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Groupe International association of diabetes and pregnancy

Hospitalier Saint Joseph; Céline Chauleur, MD, PhD, Trends in glyburide compared with insulin use for

gestational diabetes treatment in the United States, study groups recommendations on the diagnosis

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Centre and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy.

Hospitalier Universitaire de Saint Etienne; Catherine 2000-2011. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1177-1184.

Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676-682.

Deneux-Tharaux, MD, PhD, UMR1153–Obstetrical, 3. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ,

Perinatal and Paediatric Epidemiology (EPOPée Jeffries WS, Robinson JS; Australian Carbohydrate 17. Mamelle N, Munoz F, Grandjean H. Fetal growth

Research Team), Descartes University–INSERM, Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women Trial Group. from the AUDIPOG Study, I: establishment of

Paris; Muriel Doret, MD, PhD, Department of Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus reference curves [in French]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol

Gynecology-Obstetrics, Hôpital Femme Mère on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352 Reprod (Paris). 1996;25(1):61-70.

enfant Lyon; Anne Ego, MD, PhD, Université (24):2477-2486. 18. Cornblath M, Hawdon JM, Williams AF, et al.

Grenoble Alpes/CNRS/TIMC-IMAG UMR 5525 4. Simmons D, McElduff A, McIntyre HD, Elrishi M. Controversies regarding definition of neonatal

(Equipe ThEMAS), Grenoble; Denis Gallot, MD, PhD, Gestational diabetes mellitus: NICE for the US? hypoglycemia: suggested operational thresholds.

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Centre a comparison of the American Diabetes Association Pediatrics. 2000;105(5):1141-1145.

Hospitalier Universitaire, Clermont-Ferrand; and the American College of Obstetricians and 19. Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, et al; Eunice

François Goffinet, MD, PhD, Department of Gynecologists guidelines with the UK National Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health

Gynecology-Obstetrics, Assistance Publique– Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine

Hôpitaux de Paris, Cochin–Port Royal; Gilles Kayem, guidelines. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):34-37. Units Network. A multicenter, randomized trial of

MD, PhD, Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med.

Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Trousseau; 5. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics.

ACOG practice bulletin No. 190: gestational 2009;361(14):1339-1348.

Bruno Langer, MD, PhD, Department of

Gynecology-Obstetrics Hautepierre, Hôpitaux diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 20. Anjalakshi C, Balaji V, Balaji MS, Seshiah V.

universitaire de Strasbourg; Camille Leray, MD, PhD, 131(2):e49-e64. A prospective study comparing insulin and

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Assistance 6. Goetzl L, Wilkins I. Glyburide compared to glibenclamide in gestational diabetes mellitus in

Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Cochin–Port Royal; insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes Asian Indian women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;

Laurent Mandelbrot, MD, PhD, Department of mellitus: a cost analysis. J Perinatol. 2002;22(5): 76(3):474-475.

Gynecology-Obstetrics, Assistance Publique– 403-406. 21. Bertini AM, Silva JC, Taborda W, et al. Perinatal

Hôpitaux de Paris, Louis Mourier, Colombes; Olivier 7. Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM, outcomes and the use of oral hypoglycemic agents.

Morel, MD, PhD, Department of Gynecology- Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin J Perinat Med. 2005;33(6):519-523.

Obstetrics, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl 22. Ogunyemi D, Jesse M, Davidson M. Comparison

Nancy; Frank Perrotin, MD, PhD, Department of J Med. 2000;343(16):1134-1138. of glyburide versus insulin in management of

Gynecology-Obstetrics, Centre Hospitalier gestational diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2007;13

Universitaire de Tours; Patrick Rozenberg, MD, PhD, 8. Balsells M, García-Patterson A, Solà I, Roqué M,

Gich I, Corcoy R. Glibenclamide, metformin, and (4):427-428.

Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, Centre

Hospitalier Universitaire de Poissy; Damien Subtil, insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: 23. Silva JC, Bertini AM, Taborda W, et al.

MD, PhD, Department of Gynecology-Obstetrics, a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015; Glibenclamide in the treatment for gestational

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Lille; Christophe 350:h102. diabetes mellitus in a compared study to insulin [in

Vayssiere, MD, PhD, Department of Gynecology- 9. Jiang YF, Chen XY, Ding T, Wang XF, Zhu ZN, Portuguese]. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;

Obstetrics, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Su SW. Comparative efficacy and safety of OADs in 51(4):541-546.

Toulouse; Norbert Winer, MD, PhD, Department of management of GDM: network meta-analysis of 24. Lesaffre E. Superiority, equivalence, and

Gynecology-Obstetrics, Centre Hospitalier randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. non-inferiority trials. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66

Universitaire de Nantes. 2015;100(5):2071-2080. (2):150-154.

Funding/Support: This study was funded by a 10. Moretti ME, Rezvani M, Koren G. Safety of 25. Schumi J, Wittes JT. Through the looking glass:

research grant from the French Ministry of Health glyburide for gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis understanding non-inferiority. Trials. 2011;12:106.

(PHRC 2011) and was sponsored by the Département of pregnancy outcomes. Ann Pharmacother. 2008; 26. Buschur E, Brown F, Wyckoff J. Using oral

de la Recherche Clinique et du Développement de 42(4):483-490. agents to manage gestational diabetes: what have

l’Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris. 11. Poolsup N, Suksomboon N, Amin M. Efficacy we learned? Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(2):570.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The sponsor and safety of oral antidiabetic drugs in comparison 27. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ,

designed and conducted the study but did not have to insulin in treating gestational diabetes mellitus: Altman DG; CONSORT Group. Reporting of

any role in the collection, management, analysis, a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109985. noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials:

and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, 12. Song R, Chen L, Chen Y, et al. Comparison of extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA.

or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit glyburide and insulin in the management of 2012;308(24):2594-2604.

the manuscript for publication. gestational diabetes: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 28. Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software Release

Additional Contributions: We thank Laurence 2017;12(8):e0182488. 14. College Station, TX: Stata Corp; 2015.

Lecomte-Raclet, PhD, Laurence Bussiere, PhD, 13. Zeng YC, Li MJ, Chen Y, et al. The use of

Sabine Le Levier, MSc, and Eric Dufour, PhD, Unité 29. McKinlay CJ, Alsweiler JM, Ansell JM, et al;

glyburide in the management of gestational CHYLD Study Group. Neonatal glycemia and

de Recherche Clinique-Centre Investigation diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Adv Med Sci.

Clinique Paris Descartes Necker-Cochin, for neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years. N Engl J

2014;59(1):95-101. Med. 2015;373(16):1507-1518.

implementation, monitoring, and data

management of the study, and Shohreh Azimi, MSc, 14. Camelo Castillo W, Boggess K, Stürmer T, 30. Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. Noninferiority trials: is a new

project manager, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Brookhart MA, Benjamin DK Jr, Jonsson Funk M. treatment almost as effective as another? JAMA.

Paris, for data collection and management. They Association of adverse pregnancy outcomes with 2015;313(23):2371-2372.

have not received any compensation for their roles glyburide vs insulin in women with gestational

in the study. We also thank David Marsh, BSc, PhD, diabetes. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(5):452-458.

freelance translator and copyeditor/proofreader, 15. Cheng YW, Chung JH, Block-Kurbisch I, Inturrisi

for language editing. He received compensation M, Caughey AB. Treatment of gestational diabetes

for this work.

1780 JAMA May 1, 2018 Volume 319, Number 17 (Reprinted) jama.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/22/2022

You might also like

- Student Exploration: Human KaryotypingDocument5 pagesStudent Exploration: Human KaryotypingTurkan Amirova75% (4)

- NCP Impaired Skin IntegrityDocument2 pagesNCP Impaired Skin IntegrityLiza Marie Cayetano Adarne93% (14)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument20 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-347153077No ratings yet

- How To Implement An Aba ProgramDocument15 pagesHow To Implement An Aba ProgramGiedrė SkaisgirytėNo ratings yet

- Maternal & Child Practice Exam 4 - RNpediaDocument21 pagesMaternal & Child Practice Exam 4 - RNpediaLot Rosit100% (2)

- Rciu TaiwanDocument4 pagesRciu TaiwanKatherine Janneth Muñoz NogueraNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Point/counterpointDocument10 pagesPharmacological Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Point/counterpointsaryindrianyNo ratings yet

- Contribution of Liraglutide in The Fixed-Ratio Combination of Insulin Degludec and Liraglutide (Ideglira)Document8 pagesContribution of Liraglutide in The Fixed-Ratio Combination of Insulin Degludec and Liraglutide (Ideglira)rakolovaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Glyburide and Insulin in The Man PDFDocument18 pagesComparison of Glyburide and Insulin in The Man PDFwinda istikhomahNo ratings yet

- TugasDocument12 pagesTugasLola SantiaNo ratings yet

- Metformin Vs Insulin in Gestational DiabetesDocument17 pagesMetformin Vs Insulin in Gestational Diabetesmiguel alejandro zapata olayaNo ratings yet

- Zaharah KurniawatiDocument6 pagesZaharah KurniawatiIhdina Hanifa Hasanal IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Effect of Inositol Sterioisomers at Different Dosages in Gestational DiabetesDocument8 pagesEffect of Inositol Sterioisomers at Different Dosages in Gestational DiabetesMohsin HassamNo ratings yet

- Metformin in PregnancyDocument31 pagesMetformin in PregnancyPrashant SardaNo ratings yet

- Study of Lipid Profile in Hypertensive Disorders of PregnancyDocument10 pagesStudy of Lipid Profile in Hypertensive Disorders of PregnancyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Association of Maternal Triglyceride Responses To Thyroid Function in Early Pregnancy With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus PDFDocument12 pagesAssociation of Maternal Triglyceride Responses To Thyroid Function in Early Pregnancy With Gestational Diabetes Mellitus PDFxiaoqingNo ratings yet

- Feig 2017Document13 pagesFeig 2017Lembaga Pendidikan dan PelayananNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyDocument8 pagesEuropean Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyJose Alejandro InciongNo ratings yet

- Effect of Gabapentin On Hyperemesis Gravidarum: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEffect of Gabapentin On Hyperemesis Gravidarum: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled TrialAngie MNo ratings yet

- Intl J Gynecology Obste - 2023 - Kouiti - Replacement of Watching Television With Physical Activity and The Change inDocument8 pagesIntl J Gynecology Obste - 2023 - Kouiti - Replacement of Watching Television With Physical Activity and The Change inlucynag1997No ratings yet

- To Study Effect of Medical Nutrition Therapy in Patients of Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument4 pagesTo Study Effect of Medical Nutrition Therapy in Patients of Gestational Diabetes MellitusIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide For Adolescents With ObesityDocument12 pagesA Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide For Adolescents With ObesityWarun KumarNo ratings yet

- Treatments For Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument14 pagesTreatments For Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisSofía Simpértigue CubillosNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 1509819Document10 pagesNej Mo A 1509819Fhirastika AnnishaNo ratings yet

- Metformin Vs Insulin GDMDocument20 pagesMetformin Vs Insulin GDMBrenda ValdespinoNo ratings yet

- A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide For Adolescents With ObesityDocument12 pagesA Randomized, Controlled Trial of Liraglutide For Adolescents With ObesityJosé Luis ChavesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Obgyn 3Document29 pagesJurnal Obgyn 3giselaNo ratings yet

- InsulinaDocument8 pagesInsulinaClaudiu SufleaNo ratings yet

- Myo-Inositol Supplementation and Onset of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Pregnant Women With A Family History of Type 2 DiabetesDocument4 pagesMyo-Inositol Supplementation and Onset of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Pregnant Women With A Family History of Type 2 DiabetesAnca CucuNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes SMFM PDFDocument3 pagesGestational Diabetes SMFM PDFAnanto PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document5 pagesJurnal 2Rizqi Fauzi Nurul AwalinNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 0810625Document15 pagesNej Mo A 0810625Catherine MorrisNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Definition, Aetiological and Clinical AspectsDocument9 pagesGestational Diabetes Mellitus: Definition, Aetiological and Clinical AspectsantonellamartNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Alun 3Document11 pagesJurnal Alun 3Dwi PurwantiNo ratings yet

- I J R P S: Metformin Compared To Insulin For The Management of Gestational DiabeticDocument5 pagesI J R P S: Metformin Compared To Insulin For The Management of Gestational DiabeticAbed AlhaleemNo ratings yet

- Effect of Gabapentin On Hyperemesis Gravidarum: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled TrialDocument9 pagesEffect of Gabapentin On Hyperemesis Gravidarum: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled TrialKukuh PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Screening PIT POGI 2023Document62 pagesAntenatal Screening PIT POGI 2023Rachmat HasanNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study For Efficacy of Termination in First Trimester Pregnancy Using Misoprostol and MifepristoneDocument9 pagesComparative Study For Efficacy of Termination in First Trimester Pregnancy Using Misoprostol and MifepristonePeertechz Publications Inc.No ratings yet

- Outi Pellonper A, Kati Mokkala, Noora Houttu, Tero Vahlberg, Ella Koivuniemi, Kristiina Tertti, Tapani R Onnemaa, and Kirsi LaitinenDocument9 pagesOuti Pellonper A, Kati Mokkala, Noora Houttu, Tero Vahlberg, Ella Koivuniemi, Kristiina Tertti, Tapani R Onnemaa, and Kirsi LaitinenLisa Citrawildani07No ratings yet

- Joi 160014Document10 pagesJoi 160014Rush32No ratings yet

- Metformin For GDMDocument7 pagesMetformin For GDMRoro WidyastutiNo ratings yet

- Campbell 2017Document3 pagesCampbell 2017Muhammad IqsanNo ratings yet

- 11 ORATILE. P. ROBERTO OLMOSTrat. Con Dieta y EjercicoDocument8 pages11 ORATILE. P. ROBERTO OLMOSTrat. Con Dieta y Ejercicoiriartenela14No ratings yet

- HipoDocument10 pagesHipoDwi atikaNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa 2206038Document12 pagesNejmoa 2206038Juan David Arboleda LopezNo ratings yet

- Broniscer 2013Document9 pagesBroniscer 2013docadax848No ratings yet

- Tirzepatide Once Weekly For The Treatment of Obesity Nejmoa2206038Document12 pagesTirzepatide Once Weekly For The Treatment of Obesity Nejmoa2206038Salah ArafehNo ratings yet

- Post Partum Maternal Morbidities and TheDocument102 pagesPost Partum Maternal Morbidities and TheBagusHibridaNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Perinatal Outcome in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Compared To Pregestational Diabetes MellitusDocument6 pagesMaternal and Perinatal Outcome in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Compared To Pregestational Diabetes MellitusrischaNo ratings yet

- Nej Mo A 2206038Document12 pagesNej Mo A 2206038dravlamfNo ratings yet

- Effect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring On Hypoglycemia in Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument10 pagesEffect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring On Hypoglycemia in Older Adults With Type 1 Diabetes A Randomized Clinical TrialClaudia NgNo ratings yet

- VHRM 9 711 2Document7 pagesVHRM 9 711 2fenniebubuNo ratings yet

- Putra Et Al 55-58Document4 pagesPutra Et Al 55-58arga setyo adjiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Trimonthly Administration of Goserelin Acetate 10.8 MG in Premenopausal Chinese Females With Symptomatic AdenomyosisDocument7 pagesClinical Efficacy and Safety of Trimonthly Administration of Goserelin Acetate 10.8 MG in Premenopausal Chinese Females With Symptomatic Adenomyosisabdulsamadk783No ratings yet

- Same 5Document6 pagesSame 5elnadi.grafistNo ratings yet

- Medication Adherence and Glycemic Control Among Newly Diagnosed Diabetes PatientsDocument9 pagesMedication Adherence and Glycemic Control Among Newly Diagnosed Diabetes PatientsmajedNo ratings yet

- Treatment HEGDocument10 pagesTreatment HEGAnonymous 7jvQWDndVaNo ratings yet

- Physical InterventionDocument9 pagesPhysical Interventionconstantius augustoNo ratings yet

- Nice SugarDocument15 pagesNice SugarRafaela LealNo ratings yet

- Antepartum Transabdominal Amnioinfusion in Oligohydramnios - A Comparative StudyDocument4 pagesAntepartum Transabdominal Amnioinfusion in Oligohydramnios - A Comparative StudyVashti SaraswatiNo ratings yet

- Glutamina IVDocument11 pagesGlutamina IVBLADIMIR ALEJANDRO GIL VALENCIANo ratings yet

- Weight Gain and Menstrual Abnormalities Between Users of Depo-Provera and NoristeratDocument6 pagesWeight Gain and Menstrual Abnormalities Between Users of Depo-Provera and NoristeratMauricio Lopez MejiaNo ratings yet

- DEPICT 1 - T1D StudyDocument13 pagesDEPICT 1 - T1D StudyGVRNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 10: ObstetricsNo ratings yet

- Picot: Participant/ Population Intervention Comparison Outcome Type of StudyDocument2 pagesPicot: Participant/ Population Intervention Comparison Outcome Type of Studyrudy fed cruzNo ratings yet

- Sample Competency Assessment ToolDocument10 pagesSample Competency Assessment ToolHengkyNo ratings yet

- Specialiazed Job DescriptionsDocument19 pagesSpecialiazed Job DescriptionsBGHMC SURGERYNo ratings yet

- Michael Fraser BookletDocument5 pagesMichael Fraser BookletRushika PurohitNo ratings yet

- Surgical Assisting AssignmentDocument3 pagesSurgical Assisting AssignmentSarah ZungailoNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Autism Spectrum Disorder Fact SheetDocument2 pagesDSM 5 Autism Spectrum Disorder Fact SheetMario MendozaNo ratings yet

- Patofisiologi StrokeDocument20 pagesPatofisiologi StrokeAkbar Dito ErlanggaNo ratings yet

- The Medical Letter: On Drugs and TherapeuticsDocument4 pagesThe Medical Letter: On Drugs and TherapeuticsbippityNo ratings yet

- Trajectory Model enDocument5 pagesTrajectory Model enHana SafiaNo ratings yet

- HipertiroidDocument96 pagesHipertiroidOja KarnilaNo ratings yet

- CYW ACE-Q (User Guide) PDFDocument21 pagesCYW ACE-Q (User Guide) PDFLaura LunguNo ratings yet

- The Health-Giving Cup Cyprian's Ep. 63 and The Medicinal Power of Eucharistic WineDocument24 pagesThe Health-Giving Cup Cyprian's Ep. 63 and The Medicinal Power of Eucharistic WinevictorvictorinNo ratings yet

- Escala de Amnesia Postraumatica Abreviada de Westmad (Ingles) PDFDocument3 pagesEscala de Amnesia Postraumatica Abreviada de Westmad (Ingles) PDFCARLOS ROCHELNo ratings yet

- All Absolute Statements With Words Like and Is Considered A and Is ThereforeDocument20 pagesAll Absolute Statements With Words Like and Is Considered A and Is ThereforeJohnmer AvelinoNo ratings yet

- HealOzone Brochure 01 PDFDocument5 pagesHealOzone Brochure 01 PDFAGNo ratings yet

- Case Investigation Form (CIF) - 2 PagesDocument2 pagesCase Investigation Form (CIF) - 2 PagesRexlee Alde LptNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Alzheimer's Disease With Nursing ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesPathophysiology of Alzheimer's Disease With Nursing ConsiderationsTiger Knee100% (1)

- 647 4385 1 PB1 PDFDocument198 pages647 4385 1 PB1 PDFioko iokovNo ratings yet

- Immunization Stress Related IssuesDocument77 pagesImmunization Stress Related Issuesparmita sariNo ratings yet

- CV KPM Jan 2020Document13 pagesCV KPM Jan 2020Prof. Dr. Kamlesh MehtaNo ratings yet

- NCP Ortho WardDocument2 pagesNCP Ortho WardAira MaeNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome - Review of Acute Decompensated Diabetes in Adult Patients BMJ 2019Document15 pagesDiabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Syndrome - Review of Acute Decompensated Diabetes in Adult Patients BMJ 2019capistranflorespalomaNo ratings yet

- Multiple Cranial NeuropathyDocument13 pagesMultiple Cranial NeuropathyChaerani SalamNo ratings yet

- Singh Et Al, 2020Document2 pagesSingh Et Al, 2020Julia BNo ratings yet

- 10 1136@vr 147 25 709Document5 pages10 1136@vr 147 25 709Erick ManosalvasNo ratings yet

- Translation Needed - Claim 69305474 - VietnameseDocument19 pagesTranslation Needed - Claim 69305474 - VietnameseLyon HuynhNo ratings yet