Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Covid y Traqueostomía

Uploaded by

Catalina Muñoz VelasquezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Covid y Traqueostomía

Uploaded by

Catalina Muñoz VelasquezCopyright:

Available Formats

NTSP considerations for tracheostomy in the COVID-19 outbreak

Updated 31-3-20

Tracheostomy is performed in around 10-13% of all level 3 ICU admissions in the UK. The clinical course

of COVID-19 in the critically ill has not yet been fully characterized but there are considerations for

patients with new or existing tracheostomies, considered below. This short article considers balancing the

risks of infection control risks of aerosol spread of the virus versus the best management for the patient

with a tracheostomy.

This guide considers balancing the risks of infection control re aerosol spread of the virus versus the

best management for the patient with a tracheostomy. This guidance is written for UK hospitals but is

applicable elsewhere. You may adapt/adopt these guidelines without permission. The guidance may

change as data on tracheostomy in the COVID-19 becomes available.

Who gets a tracheostomy?

Indications from European ICUs suggest that decision making around access to critical care and organ

support is based largely on current practice; the expectation is that this stands for decisions to undertake

tracheostomy. The major indication will remain to wean from ventilation when a primary extubation is

not possible or has failed.

Currently, in-hospital mortality is around 20% for ICU patient requiring tracheostomy. A tracheostomy

may not be in a patients’ best interests if the prospects of long-term independent survival are limited. The

mortality of ventilated patients with COVID pneumonitis appears to be around 50%. However, outcomes

are heavily influenced by admission criteria and the country/healthcare system reporting these data.

These decisions may become more focused in a resource-limited, overwhelmed system.

Tracheostomy may have some positive benefits in the COVID-19 pandemic, which may lead to earlier

consideration than in normal practice:

• Tracheostomy offers a ‘sealed’ system for ongoing respiratory support which may be preferable to a

primary extubation with a high chance of failure and/or the requirement for NIV/High Flow Oxygen

therapy.

• Patients with tracheostomy are typically managed with reduced or no sedation. This may allow for:

o Less intensive nursing care (the patient may be able to assist in moving, rolling).

o Fewer pumps (advantageous if there is a shortage of drugs or devices).

o Care may be overseen by non-ICU staff (who aren’t as experienced in managing sedation

perhaps).

o However, a more awake patient can be more difficult to manage, and staff must be able to safely

care for tracheostomised patients. (There may be a role for ORL/ENT/MaxFax staff here).

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Timing of tracheostomy in COVID-19

There is no consistent guidance to help clinical staff plan the most appropriate time to perform a

tracheostomy in the critically ill. Outside of the COVID pandemic, there are some groups who would clearly

benefit from an early tracheostomy. There is evidence that some neurosurgical patients or some with

short/medium-term neurological conditions can reduce ICU and hospital length of stay with an early

tracheostomy. Patients who need medium-term respiratory support also benefit, but this group is difficult

to characterise early in their ICU stay.

The data available from international colleagues and from the literature available suggests that the acute

lung injury phase of those patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis lasts around 10-14 days. For those patients

who are invasively ventilated, those who tolerate critical illness and the necessary support, can anticipate

an ICU stay of at least 10-14 days, probably longer in many. These estimates may change as the pandemic

unfolds, but the clinical experience in Europe supports these observations from other countries.

Our understanding of what constitutes a ‘COVID-positive’ or an ‘infective’ case is also evolving. Testing is

based on identification of viral RNA by PCR. The reliability of these tests is variable, with tracheal aspirates

preferable to mucosal swabs. PCR positivity might not equate to infectiousness. Some evidence shows

that samples with viral load <5 log copies per ml do not yield live virus (ie a ‘positive test’ does not always

mean ‘infectious’). A patient who has mounted an appropriate immune response is not likely to be

infectious, although the criteria to judge this and the associated antibody tests are currently being refined.

It is likely that the viral load will be low in patients by 3 weeks after the development of symptoms. Most

centres are considering that two negative COVID viral PCR tests mean that the patient can be considered

non-infectious. Virus has been detected for prolonged periods in the critically ill, however.

There may be an appropriate clinical requirement to undertake tracheostomy before the patient is

considered negative/non-infectious. For example, patients predicted to fail a primary extubation or those

with an airway problem.

The clinically appropriate window for performing tracheostomy is likely to fall within the overlapping

window whereby the patient becomes non-infectious. Given that tracheostomy is a high-risk procedure

for generating aerosols, in order to protect staff that are involved in tracheostomy procedures, we

recommend that clinicians consider that any critically ill patient recovering from COVID-19 pneumonitis

is considered high risk of infection to staff during tracheostomy insertion.

This has implications for the location and conduct of the procedure, considered below.

In summary:

• Delay tracheostomy if possible until the patient is considered COVID-negative / non-infective.

• Timing of tracheostomy must balance the risks of prolonged trans-laryngeal intubation for the

patient with the risks to the clinical staff involved in the procedure.

• Consider all critically ill patients recovering from COVID-19 pneumonitis as high risk.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Practical management of the ventilated tracheostomy patient with COVID-19

• Positive pressure support/ventilation increases the potential aerosol risks to staff

• PPE as per local/national guidelines.

• A cuff inflated, closed system is the most likely to prevent cross-contamination of staff, equipment,

other patients.

• Closed suction should be mandatory.

• Consider reducing the frequency of cleaning/inspecting the inner cannulae, or whether this should be

used at all. (Risk assess daily). Thick secretions or any time spent on an open system should be

indications to use an inner cannula.

• Cuff deflation as part of weaning, will increase aerosol generation and so the patient should ether be

in a side room or in a cohort area with other COVID-19 patients. Staff will need to wear PPE, especially

if the patient is still managed with a ventilator or a system providing CPAP.

• It may be possible to group weaning tracheostomised patients together which may facilitate cuff

deflation strategies. Successful and prompt weaning requires experienced multidisciplinary staff, who

would all need to wear appropriate PPE in this environment.

• Hospitalised patients who are normally managed with an un-cuffed tracheostomy (typically the long-

term ventilated in the community) will require a trachy change to a cuffed tube and ventilation with a

closed system in a critical care environment. This will remove the ability to vocalise (if present). If a

cohort area exists where cuff deflation or CPAP is occurring, then this is an option,

Practical management of the non-ventilated tracheostomy patient with COVID-19

• PPE as per local/national guidelines

• These patients will need an ‘open’ humidification system (ranging from a Buchanan bib or similar

simple HME device) through to active warmed humidification.

• Supplemental oxygen may be required, delivered by a trache-mask (offers some protection to the

immediate environmental droplet spread).

• These patients should be considered in the same category as any other COVID-19 patient who requires

hospitalization and/or oxygen therapy.

• They will need managing by specialist staff, trained to manage patients with tracheostomy. They will

need high-risk (to staff) airway interventions such as suctioning and inner cannula care.

• A simple face mask may be applied over the face if the cuff is deflated to minimize droplet spread

from the patient.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Where to manage a patient with a tracheostomy?

There are likely to be competing priorities when considering at hospital/strategic level where best to

manage patients with a tracheostomy in hospitals during the pandemic. It is likely that a significant rise in

the in-hospital population of tracheostomised patients will occur.

• Patients may be COVID-19 +ve, suspected +ve, or -ve.

• Patients may need invasive ventilation.

• Patients need to be managed by staff who are trained in tracheostomy care to:

o Prevent problems through basic care, done well.

o Detect red flags and warning signs early through education.

o Know how to troubleshoot problems and manage emergencies through education and

rehearsal.

Trachy-safe Appropriate

location COVID location

We recommend that at least one member of staff is appropriately trained to safely manage tracheostomy

problems in each cohort location that tracheostomy patients are managed in. This standard should apply

around the clock. Refresher resources are available from the links below.

Patients managed with a ‘closed system’ (cuff up and HME/ventilator) can be managed in COVID-positive

cohort locations alongside similar patients (typically an ICU) with appropriate precautions.

Patients managed with cuff deflation and pressure support/ventilation should be considered as high risk

to staff due to aerosol spread. Patients should be managed in a contained cohort area (see table below)

recognising that the majority of hospitals have limited access to these facilities.

Tier of

Recommended Location

Recommendation

1 Negative pressure single occupancy room with antechamber

2 Negative pressure single occupancy room without antechamber

3 Standard single occupancy room with HEPA / virus filter

4 Negative pressure (closed door) cohort area/bay

5 Negative pressure (closed door) cohort area/bay with HEPA / virus filter

6 Closed door cohort area

Patients managed with cuff deflation without ventilation should be managed in cohort areas depending

on their COVID status. Airway interventions and practical tracheostomy management are still considered

high risk to staff as aerosols can be generated by coughing associated with tracheostomy care. COVID

negative patients that are considered non-infective can be managed using standard precautions.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Emergency management

• Emergency care should continue as per the NTSP guidelines.

• Airway interventions should be planned where possible to allow appropriate PPE to be applied.

• It is likely that a member of staff in a cohort area will be wearing at least some appropriate PPE

at the time of an airway emergency – call for help.

• PPE should be immediately available in areas that COVID-19 positive tracheostomy patients are

managed in.

• Staff should ensure that they protect themselves in order to best care for our patients.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Performing a new tracheostomy

The likelihood is that the majority of elective ICU tracheostomies in the coming months will be for COVID-

19 related respiratory failure and to facilitate weaning from mechanical ventilation.

ORL/ENT/MaxFax surgical teams may be available to help with procedures (less elective work) and should

be used. Nursing staff from these areas may be invaluable if there is a sharp increase in the ICU population

with tracheostomy.

• See ENT-UK or relevant surgical guidelines

• Local Safety Standards for Invasive Procedures (LocSSIps) MUST be used

• Plan, rehearse, check and stay safe

• Pre-procedural discussions and detailed planning are essential before donning PPE and

collecting the patient

Location

Tracheostomy procedures may be performed in the ICU or in new, unfamiliar environments, depending

on where the patient is being managed and the prevailing infection control measures. If new teams or

locations are being used– ensure that the appropriate equipment, staff and support are available,

including lighting and the ability to position the patient.

For surgeons; note ICU beds are often much wider than a theatre table, with no isolated head support.

This limits surgical access. Consider bringing the patient to the side of the bed nearer the primary surgeon,

although this limits the access for an assistant.

If it looks difficult (especially an obese patient) then consider moving to the OR rather than a sub-optimal

location and accepting whatever infection control measures this entails.

Moving a critically ill patient to the OR carries its own risks which much be balanced on an individual basis

by the teams involved the procedure.

If you are going to perform the procedure on the ICU, plan to undertake it in the same location that you

would electively intubate a COVID-positive patient in, with appropriate PPE.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Practical considerations for new tracheostomy

• The PPE might restrict views for the operator and the rest of the team. It also makes

communication more difficult. Minimize noise and discuss/rehearse beforehand.

• Agree beforehand what the team will do and discuss the case in detail before you get to the

bedside.

• Check you can see what you are doing in whatever PPE you need to use.

• The procedure will inevitably generate aerosols in a ventilator-dependent patient. When the

neck is punctured, dilated or opened surgically, consider reducing the ventilatory pressures

and/or frequency to minimize aerosol generation if the patient condition allows. Consider

suspending ventilation if possible. An experienced anaesthetist or intensivist should manage the

‘top end’.

• Think about the best location for tracheostomy and think about nearby patients, staff and

equipment.

• The ideal location is in a (negative pressure) side room or a theatre suite (with the problems of

transfer).

• Take minimal staff.

• Use the most experienced staff (who will probably be the quickest).

• Consider a travelling trachy team – perform insertions and review existing patients.

• Liaise now with ORL/ENT/MaxFax surgical teams, medical and nursing colleagues.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Percutaneous or surgical tracheostomy?

It is possible to insert a tracheostomy safely using a surgical, percutaneous or hybrid technique. We

recommend that operators undertake the procedure with which they are most familiar.

Modifications to the surgical technique are described by ENT-UK and other groups. Briefly these comprise

steps to minimize aerosol generation when the trachea is opened or punctured:

• Surgical ties in preference to diathermy may reduce vapour plumes

• Advance the tracheal tube beyond the surgical window to protect the cuff

• It may be possible to use the ICU ventilator for transfer, theatre and afterwards (minimizing circuit

changes)

o Check before the procedure

o Only use equipment that operators are familiar with

• Pre-oxygenate; then cease ventilation and open circuit valves prior to opening the trachea

• Consider clamping tracheal tube (subglottic suction tubes can be damaged and manipulating the

tube may displace it)

• Prepare the breathing circuit

• Resume ventilation when a cuff-inflated sealed system is established

We recommend that only use cuffed, non-fenestrated tracheostomy tubes are used. It is important to

meticulously check the position of the tube in the 30-degree ‘ICU nursing’ position in which the patient

will spend the next few days or weeks. This should minimise the requirement for inspection or

manipulation of a tracheostomy tube following the procedure.

We do not recommend that airway endoscopy is routinely undertaken. Airway endoscopy during

percutaneous tracheostomy is recommended and is widely considered to improve the safety of the

procedure. It is likely that aerosol generation can be better controlled with an open surgical or hybrid

procedure, although this depends on the experience of staff involved in the procedure.

It is likely that the knowledge base around tracheostomy insertion in COVID-positive patients will evolve

and we aim to learn together what the best practices are for the safety of staff and for our patients.

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

Existing patients with tracheostomies

Current in-patients

• In-patients are at an unknown risk of COVID-19 form visitors and staff

o Plan where a patient would go if they developed symptoms.

o What if they had an altered airway, or tracheostomy and need specialist care?

o Plan ahead.

Current out-patients

• If a patient with a tracheostomy needs ventilator support, then they will need a cuffed

tracheostomy inserting and management in a critical care location.

• A suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient who does not need ventilatory support will need

managing in a cohort area. These locations will need staff who are trained and competent to

manage tracheostomies and their potential complications.

• During the peak of the pandemic, there is a high probability that patients from the community who

develop respiratory symptoms are COVID positive. Patients should be treated as positive until

proven negative.

Existing patients with laryngectomies

Patients who have neck-only-breathing laryngectomees don’t have the nasal ‘filters’ and intuitively they

are at greater risk of viral infection.

These patients should be contacted and offer advice. See http://dribrook.blogspot.com/

Some sensible, practical advice may also be relevant for hospitalised laryngectomy patients:

• Wear a stomal HME filter (not all HMEs perform equally).

• Hands-free valves minimize touching of the stoma.

• Ask the patient to manage as much of their stoma care as possible.

All multidisciplinary staff involved in tracheostomy care are advised to be familiar with the safety

resources and best practices for quality improvement available at:

• www.globaltrach.org

• www.tracheostomy.org.uk

• New e-learning tracheostomy modules at e-learning for Healthcare https://portal.e-lfh.org.uk

• Data collection and adoption best practices are strongly encouraged

31st March 2020 www.tracheostomy.org.uk

You might also like

- The - ASAM - Principles - of - Addiction - Medicine - (SECTION - 6 - Management - of - Intoxication - and - Withdrawal) 2Document34 pagesThe - ASAM - Principles - of - Addiction - Medicine - (SECTION - 6 - Management - of - Intoxication - and - Withdrawal) 2Susan RashidNo ratings yet

- Sexual Assault InjuryDocument3 pagesSexual Assault InjuryJMarkowitzNo ratings yet

- Adult and Paediatric Oral/nasal-Pharyngeal SuctioningDocument13 pagesAdult and Paediatric Oral/nasal-Pharyngeal SuctioningRuby Dela RamaNo ratings yet

- Dermatoloji HandbookDocument76 pagesDermatoloji Handbookedi büdü100% (1)

- Care Bundle For Insertion and Maintenance of Central Venous Catheters Within The Renal and Transplant UnitDocument14 pagesCare Bundle For Insertion and Maintenance of Central Venous Catheters Within The Renal and Transplant Unitnavjav100% (1)

- Airway Management Inside and Outside Operating Rooms 2018 British Journal ofDocument3 pagesAirway Management Inside and Outside Operating Rooms 2018 British Journal ofSeveNNo ratings yet

- Normal and Pathological Bronchial Semiology: A Visual ApproachFrom EverandNormal and Pathological Bronchial Semiology: A Visual ApproachPierre Philippe BaldeyrouNo ratings yet

- Mental Retardation Lesson PlanDocument10 pagesMental Retardation Lesson Plansp2056251No ratings yet

- Script Forum (Moderator)Document3 pagesScript Forum (Moderator)aisyah83% (36)

- 02a - PPE - Summary and Rationale For RecommendationsDocument2 pages02a - PPE - Summary and Rationale For RecommendationsMohammedNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia and Caring For Patients During The COVID-19 OutbreakDocument8 pagesAnaesthesia and Caring For Patients During The COVID-19 OutbreakMuhammad RenaldiNo ratings yet

- Tracheostomy in The COVID 19 PandemicDocument3 pagesTracheostomy in The COVID 19 PandemicKenjiNo ratings yet

- COVID Tracheostomy Guidance - CompressedDocument6 pagesCOVID Tracheostomy Guidance - CompressedMary GalvezNo ratings yet

- Annex 40 INTERIM GUIDELINES ON RESUSCITATION DURING COVID19 PANDEMICDocument15 pagesAnnex 40 INTERIM GUIDELINES ON RESUSCITATION DURING COVID19 PANDEMICAzran Shariman HasshimNo ratings yet

- Guideline For Conservation of Respiratory Protection ResourcesDocument14 pagesGuideline For Conservation of Respiratory Protection ResourcesAMEU URGENCIASNo ratings yet

- Bahan Referat Eria 6Document11 pagesBahan Referat Eria 6Eva Devita SariNo ratings yet

- %pediatric TracheostomyDocument25 pages%pediatric TracheostomyFabian Camelo OtorrinoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Management of Tracheal Intubation in Critically Ill AdultsDocument26 pagesGuidelines For The Management of Tracheal Intubation in Critically Ill AdultsFemiko Panji AprilioNo ratings yet

- Tracheostomy Management During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument3 pagesTracheostomy Management During The COVID-19 Pandemicika lestariNo ratings yet

- AO CMF COVID-19 Task Force Guidelines v1-6 PDFDocument8 pagesAO CMF COVID-19 Task Force Guidelines v1-6 PDFadhityaNo ratings yet

- APSS 2D Ventilator Associated Pneumonia VAPDocument6 pagesAPSS 2D Ventilator Associated Pneumonia VAPdadiNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus RCOphth Update March 18th 1Document8 pagesCoronavirus RCOphth Update March 18th 1charoiteNo ratings yet

- UHMS Guidelines - COVID-19 V4Document3 pagesUHMS Guidelines - COVID-19 V4Juan CruzNo ratings yet

- Walls 8093 CH 01Document7 pagesWalls 8093 CH 01Adriana MartinezNo ratings yet

- 2020-08 Tracheostomy - Care - Guidance - FinalDocument44 pages2020-08 Tracheostomy - Care - Guidance - FinalKatherine AzocarNo ratings yet

- CDC AerosolDocument5 pagesCDC Aerosolwiwik sNo ratings yet

- CCJM 87a ccc033 FullDocument4 pagesCCJM 87a ccc033 FullKamar Operasi Hermina BogorNo ratings yet

- Guidance On The Use of Personal Protective Equipment Ppe in Hospitals During The Covid 19 OutbreakDocument9 pagesGuidance On The Use of Personal Protective Equipment Ppe in Hospitals During The Covid 19 OutbreakGerlan Madrid MingoNo ratings yet

- AABIP Statement On Bronchoscopy COVID - 3 12 2020 Statement Plus 3 19 2020 Updates V3Document5 pagesAABIP Statement On Bronchoscopy COVID - 3 12 2020 Statement Plus 3 19 2020 Updates V3garinda almadutaNo ratings yet

- Recommendations For Prehospital Airway Management in Patients With Suspected COVID-19 InfectionDocument5 pagesRecommendations For Prehospital Airway Management in Patients With Suspected COVID-19 InfectionConnor StephensonNo ratings yet

- Covid-19: Negative Pressure Rooms: Anmf Evidence BriefDocument5 pagesCovid-19: Negative Pressure Rooms: Anmf Evidence BriefninesuNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Tract InfectionsDocument26 pagesRespiratory Tract InfectionsyousefismailrootNo ratings yet

- ASA Staff Safety For COVID-19: StatementDocument8 pagesASA Staff Safety For COVID-19: StatementAbidi HichemNo ratings yet

- Hemodialysis Unit Preparedness COVID-19 Pandemic: During and AfterDocument8 pagesHemodialysis Unit Preparedness COVID-19 Pandemic: During and Afteryanuar esthoNo ratings yet

- BMJ BMJ: British Medical Journal: This Content Downloaded From 103.25.55.252 On Mon, 23 May 2016 05:18:53 UTCDocument5 pagesBMJ BMJ: British Medical Journal: This Content Downloaded From 103.25.55.252 On Mon, 23 May 2016 05:18:53 UTCNurul BariyyahNo ratings yet

- C0063 Specialty Guide - Respiratory and Coronavirus - v1 - 26 MarchDocument4 pagesC0063 Specialty Guide - Respiratory and Coronavirus - v1 - 26 MarchKevo VillagranNo ratings yet

- Via Aerea COVID 19Document3 pagesVia Aerea COVID 19zunarodriguezleoNo ratings yet

- Standard Operating ProcedureDocument15 pagesStandard Operating ProcedureAyman AliNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On PneumothoraxDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Pneumothoraxgz8xbnex100% (1)

- Issues Related To Kidney Disease and HypertensionDocument12 pagesIssues Related To Kidney Disease and HypertensionCarlos Huaman ZevallosNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Physiotherapy Guidelines For Managing Patients With Covid or of Unknown Covid Status 15nov21 - 0Document4 pagesRespiratory Physiotherapy Guidelines For Managing Patients With Covid or of Unknown Covid Status 15nov21 - 0Gl VgNo ratings yet

- Insertion Mangement Peripheral IVCannulaDocument20 pagesInsertion Mangement Peripheral IVCannulaAadil AadilNo ratings yet

- Precautions For Intubating Patients With COVID-19: To The EditorDocument3 pagesPrecautions For Intubating Patients With COVID-19: To The EditorIvan MoralesNo ratings yet

- Ecleris Considerations NIV 05.05.20Document4 pagesEcleris Considerations NIV 05.05.20tanu wijayaNo ratings yet

- Care of Newborn On Respiratory SupportDocument40 pagesCare of Newborn On Respiratory SupportsyedNo ratings yet

- Oral Oncology: CORONA-steps For Tracheotomy in COVID-19 Patients: A Staff-Safe Method For Airway ManagementDocument3 pagesOral Oncology: CORONA-steps For Tracheotomy in COVID-19 Patients: A Staff-Safe Method For Airway ManagementCorin Boice TelloNo ratings yet

- PneumoniaDocument12 pagesPneumoniaadolfrc9200No ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Insertion and Management of Chest Drains: WWW - Dbh.nhs - UkDocument14 pagesGuidelines For The Insertion and Management of Chest Drains: WWW - Dbh.nhs - UkStevanysungNo ratings yet

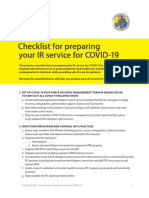

- Checklist For Preparing Your IR Service For COVID-19Document8 pagesChecklist For Preparing Your IR Service For COVID-19uroshkgNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guidelines (Nursing) : Tracheostomy ManagementDocument19 pagesClinical Guidelines (Nursing) : Tracheostomy ManagementbarbiemeNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia Management in CovidDocument4 pagesAnesthesia Management in CovidMuhammad Farooq AfzalNo ratings yet

- Center For Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Science Jamia Millia IslamiaDocument16 pagesCenter For Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Science Jamia Millia IslamiaummiNo ratings yet

- CCJM 87a ccc040 FullDocument3 pagesCCJM 87a ccc040 FullRianNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia - September 1992 - Mason - Learning Fibreoptic Intubation Fundamental ProblemsDocument3 pagesAnaesthesia - September 1992 - Mason - Learning Fibreoptic Intubation Fundamental ProblemsfoolscribdNo ratings yet

- Name: Kristella Marie C. Desiata Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesName: Kristella Marie C. Desiata Case AnalysisYamete KudasaiNo ratings yet

- Guidance For Return To Practice For Otolaryngology-Head and Neck SurgeryDocument9 pagesGuidance For Return To Practice For Otolaryngology-Head and Neck SurgeryLeslie Lindsay AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Covid19 Infection Prevention and ControlDocument70 pagesCovid19 Infection Prevention and ControlAdeuga ADEKUOYENo ratings yet

- EPP. Am. College, Surgeons.20.Document3 pagesEPP. Am. College, Surgeons.20.Mary RodriguezNo ratings yet

- CDC - Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) EventDocument13 pagesCDC - Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) EventAl MuzakkiNo ratings yet

- Managing The Respiratory Care of Patients With COVID-19Document17 pagesManaging The Respiratory Care of Patients With COVID-19ManuelNo ratings yet

- COVID 19. 4 - 13 KashmerDocument42 pagesCOVID 19. 4 - 13 KashmerIshfaq GanaiNo ratings yet

- Nasogastric Tubes PDFDocument8 pagesNasogastric Tubes PDFGyori ZsoltNo ratings yet

- Guidance For Return To Practice For Otolaryngology-Head and Neck SurgeryDocument10 pagesGuidance For Return To Practice For Otolaryngology-Head and Neck SurgeryLeslie Lindsay AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Covid Cohorting PacDocument5 pagesCovid Cohorting PacsimplyrosalynNo ratings yet

- Central Venous Surgical Catheter or Long Line, Management of A Baby WithDocument16 pagesCentral Venous Surgical Catheter or Long Line, Management of A Baby WithChiduNo ratings yet

- COVID 19: Infection Prevention and ControlDocument29 pagesCOVID 19: Infection Prevention and ControlJp Rizal IPCCNo ratings yet

- CPT Code 99091 Alexander LDocument6 pagesCPT Code 99091 Alexander LBryan MorteraNo ratings yet

- Acute Urticaria in The InfantDocument3 pagesAcute Urticaria in The InfantAle Pushoa UlloaNo ratings yet

- Vital PointsDocument72 pagesVital PointsMiracle For NursesNo ratings yet

- Bacteria Viruses Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesBacteria Viruses Lesson Planapi-665322772No ratings yet

- The Diseases of The PancreasDocument40 pagesThe Diseases of The PancreasAroosha IbrahimNo ratings yet

- 2 Pre Test TNTDocument7 pages2 Pre Test TNTHarry CenNo ratings yet

- Kalten BornDocument34 pagesKalten BornjayadevanNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan. PPT (Peer Demonstration - Herbal Plant) ..Document20 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan. PPT (Peer Demonstration - Herbal Plant) ..Curie Mae DulnuanNo ratings yet

- Disorders of PigmentationDocument68 pagesDisorders of PigmentationSajin AlexanderNo ratings yet

- 潰瘍性結腸炎臨床治療指引 2020 VersionDocument29 pages潰瘍性結腸炎臨床治療指引 2020 Version張浩哲No ratings yet

- Kleine-Levin Syndrome-A Systematic Study of 108 PatientsDocument12 pagesKleine-Levin Syndrome-A Systematic Study of 108 PatientsChon ChiNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 VocabularyDocument3 pagesUnit 4 VocabularyAndris RosinNo ratings yet

- Treatment MaligannciesDocument11 pagesTreatment MaligannciesannaNo ratings yet

- Lynch Nejm2018Document10 pagesLynch Nejm2018alomeletyNo ratings yet

- Respiratory SoundsDocument2 pagesRespiratory SoundsMuhammad NaeemjakNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy CasesDocument8 pagesPharmacotherapy CasesTop VidsNo ratings yet

- 10 3322@caac 21559Document25 pages10 3322@caac 21559DIANA ALEXANDRA RAMIREZ MONTAÑONo ratings yet

- Diffuse Midline Glioma: DR Tamajyoti GhoshDocument53 pagesDiffuse Midline Glioma: DR Tamajyoti GhoshTamajyoti Ghosh100% (1)

- Spinal AnesthesiaDocument5 pagesSpinal Anesthesiaakif48266No ratings yet

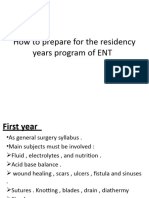

- Syllabus of Ent Residency ProgramJMOHDocument30 pagesSyllabus of Ent Residency ProgramJMOHadham bani younesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 - The HeartDocument6 pagesChapter 12 - The HeartAgnieszka WisniewskaNo ratings yet

- Dole Annual Medical Report Sample Amp GuideDocument5 pagesDole Annual Medical Report Sample Amp Guidehr.ionhotelNo ratings yet

- Medical History FormDocument2 pagesMedical History Formchamuditha dilshanNo ratings yet

- Cam4 10 1545Document5 pagesCam4 10 1545Simona VisanNo ratings yet