Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 89.215.123.18 On Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 89.215.123.18 On Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

Uploaded by

ikrambelfegasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 89.215.123.18 On Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 89.215.123.18 On Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

Uploaded by

ikrambelfegasCopyright:

Available Formats

Representing the language of the 'other': African American Vernacular English in

ethnography

Author(s): Tamara Mose Brown and Erynn Masi de Casanova

Source: Ethnography , June 2014, Vol. 15, No. 2 (June 2014), pp. 208-231

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24467145

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Ethnography

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Article Ethno graphy

Ethnography

2014, Vol. 15(2) 208-231

Representing the © The Author(s) 2013

Kepnnts ana permissions:

language of the 'other': sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1 177/14661381 12471 I 10

African American eth.sagepub.com

i>SAGE

Vernacular English in

ethnography

Tamara Mose Brown

Brooklyn College, USA

Erynn Masi de Casanova

University of Cincinnati, USA

Abstract

Ethnography is often described as the translation of culture, yet there has been

discussion of actual linguistic translation in ethnography. Many ethnographers enga

research across divides of language that require them to make decisions about how

represent the language of their informants. The privileging of academic Standard En

creates dilemmas for ethnographers whose subjects speak stigmatized languages. B

on an analysis of 32 book-length ethnographies about African Americans (reviewe

the American Journal of Sociology between 1999 and 2009), this article answers t

questions of how ethnographers typically deal with language difference in their te

particularly when research takes place across dialects of the same language, and w

language matters in the production of ethnographic texts.

Keywords

ethnography, language, linguistics, AAVE, African American Vernacular English, B

English, anthropology, culture, representation, insider/outsider

A history of ethnographic understanding - a nonprogressive, nondismissive history -

would be a story of serious, failed translations. (James Clifford 1997: 360)

This article builds on the literature on ethnographic methodology and reflex

ethnography by calling attention to the treatment of the language of resear

subjects, identifying patterns in such treatment, and suggesting how an awarene

Corresponding author:

Tamara Mose Brown, Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Department of Sociology, 2900 Be

Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210, USA.

Email: tbrown@brooklyn.cuny.edu

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose brown and Casanova 209

and inclusion of linguistic bou

written accounts. Language is

research are categorized in so

US and the world system, ling

superior and inferior. Based o

phies of African Americans in

ing with the English dialect

display varied levels of attent

resenting socially devalued di

sentation that ethnographers

and others can help ethnograp

tion and inequality that exist

more fully in the practice of et

our goals of presenting people

social research that will hold u

Why look at translation

If ethnographers have tended

unexamined (as we show in th

language now? First, how we

accounts. As sociologist Christ

Social scientists share with journ

tested the moment it is published

and whose own accounts are at

account is a translation for wh

(Churchill 2005: 7)

Although Churchill is discuss

of the situation', the same co

writer of an ethnographic ac

work of translation or transc

brackets, the readers of that

tions, in which translated tex

truthfulness or faithfulness

difficult to assess the translat

pher writing about fieldwork

pants' speech in Standard Eng

unexaminable, yet the decisio

quential for readers' understand

also socially and culturally relev

by social scientists (Heath 197

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

210 Ethnography 15(2)

Second, the representation o

measure of how 'in' the resea

If an ethnographer presents

the research participants, th

used in the field and how i

writer is not a native speaker

methodological challenges, o

dialect of the study particip

'has as much or more to do w

into their [the participants']

ethnographic report' (Chur

there is a two-fold aberration

the spoken words of the part

ethnographer's own reality

are simultaneously negotiat

Contemporary ethnograph

represent 'others' - people wh

terms of race, socioeconom

ology encourages us to be

researchers have taken thes

graphic practice.3 Ethnogra

must consider the ethical is

populations. As the socioling

teaches us, 'There can be n

social world, without a deta

life' (Davies and Mehan 200

adapt vernacular speech su

to the rules of Standard En

this translation and represe

and subsequent thinkers th

through the tension of diffe

originality of the presence

Indeed, ethnographers of m

'others'. In studying ethnog

even the most reflexive resea

sent the language of their re

discuss how they translate or

unique challenges they may e

African American Vernacul

The language divides crossed

subtle, and yet equally as sign

a completely different lang

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 211

used by some African America

anthropological literature, inc

Paris 2009), African Americ

(Cutler 2003), Hip Hop Nati

(Labov 1972, 1982; Spears 198

cally-driven 'Ebonics' (Fordham

American Vernacular English (

(Bailey 2001; Chun 2001; Dayto

Davies and Mehan analyze so

grammatical structures, highli

interaction, and social institution

manipulations of language and

Language, then, must be made

make sense of everyday inter

example, we can see how the m

ing its speakers.

Many linguists have demonstr

through its unique structure.

methods, sociolinguistics, and

1972 Language in the Inner Cit

laid out the grammar of Black E

rooted in the southern Unite

Labov's, had demonstrated the

based on her previous resear

Linguist John Baugh (1983), st

Los Angeles, wrote about the

Americans who have limited contact with other dialects.

Labov discusses the ways in which the institutional and residential segregation

of African Americans has contributed to the continuous development of AAVE as

an 'elegant form of expression' (Labov 2010: 24). He also illustrates, as do both

Bailey and Baugh, how AAVE is used to unify an oppressed group through dis

tinctive syntax, grammatical markers, and semantic content. The changes in this

language over time have been more rapid in some parts of the US, and are affected

by verbal interactions with other English dialects outside the community (Labov

2010). Labov (2010) argues that these changes over time, as inner city youth inter

act more with varieties of 'White' English, will bring about the demise of AAVE

dialect and the linguistic community it creates, which he sees as preferable to the

continued injustice of residential segregation that maintains and innovates AAVE.

The idea of community identity through language stems from earlier studies by

anthropologist Roger Abrahams (1962, 1972), who illustrated how the everyday

life of African Americans contributes to their cultural and place-based identities,

and advocated for ethnographers to use the analysis of language in their studies.

With the wealth of research on language as resistance and the unique structures of

AAVE, it is astonishing that 25 out of 30 ethnographers researching African

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

212 Ethnography 15(2)

American communities in o

choosing not to discuss thei

of participants' AAVE speec

sample do little to discuss th

the sociolinguistic choices o

analysis that was eventuall

important as it clarifies fo

the researcher and particip

researchers have a privilege

who are relatively subordin

ethnographies we reviewed

their publications. This negle

call for more language reflex

how social class is reproduc

Basil Bernstein's work). Altho

writing and the similarity of

tion of habitus, Basil Berns

and teacher/student relatio

pant through language fram

nication' (Sadovnik 2001: 61

perpetuate inequality.

Urban ethnographers parti

their participants when the

ance and a means of markin

inequality, urban ethnograp

participate in the same raci

Appendix 1 for location of

avoiding inaccurate translatio

as we explain in this article

rapher represents the 'other'

Native speakers and the in

Much has been made in the

vantages of the researcher

1979; Duneier 1991; Jacobs-

distinct insider/outsider d

researchers may be simultane

in nationality, for example

themselves insiders simply b

culture; however, their prese

No one is ever entirely an

researcher in an outsider's p

ics with their participants. C

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 213

speakers researching members

Portuguese speakers doing fieldw

than if their first language wer

speaking AAVE in their commun

their African American research

insider positioning - being a 'na

jects - untangle the knot of ho

English) academic writing?

There has been a great debate in

over what constitutes a native spe

or refers to a discrete category

Recent literature has focused on t

speaker for social interaction an

work questions simplistic assum

ings or usage of their 'own' lang

Roberts and Harden 1997). Our

doubt on the notion that native sp

will place more importance on la

Likewise, in the ethnographies of

clear correlation between the au

use of AAVE and their level of a

discuss the salience of language in

fieldnotes and interview notes evolved into books. In the rare cases that attention

was paid to 'translation' from AAVE to Standard English (or the decision not to

translate), both black and non-black researchers formed part of the more linguis

tically-aware group of writers. Thus, African American researchers who are 'native'

speakers of AAVE tend not to discuss language in greater detail than writers who

are not 'insiders'. Leaving research to 'native speakers' does not automatically

resolve the difficulties in translation or diminish the need for the type of linguistic

awareness that this article proposes.

Methods

To examine the patterns in representation of 'other' languages, we focu

book-length ethnographies that had come to light in the past decade. To

that the books we chose were of scholarly interest and had attracted atte

their respective fields, we used the criteria of having been reviewed in the 'f

journal of the field. We selected book-length ethnographies of African Am

in the US that were reviewed in the American Journal of Sociology (AJS

1999 to 2009. AJS is the top-ranked sociology journal in the United Stat

books drawn from the AJS reviews had to meet the criteria of focusin

population that was primarily made up of African Americans. Edited v

were excluded from our study.4

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

214 Ethnography 15(2)

Once the list of reviewed

works for further analysi

tions, including whether AA

ation on the distinctive ch

literature); whether explici

participants' speech in the

terms was present); what reg

whether the author was po

language. The answers to th

descriptive statistics identify

Results

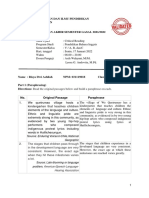

Table 1 shows how authors of African American ethnographies talk (or don't

about language. Of the ethnographies, 50 percent show the participants speaking

African American Vernacular English: exemplifying the grammar, syntax, an

pronunciations associated with this dialect of English. Yet only 16 percent of

ethnographies included any discussion of how language was transcribed in the tex

with some of these citing Black English as a standard used to present particip

authentically. While more than 90 percent of the ethnographies contain larg

tions of text representing participants' speech (verbatim quotes or narratives), it

surprising that only two ethnographies contain a dedicated language section w

AAVE grammar, words and pronunciation are addressed in detail. Most of

authors did not inform readers of their own proficiency as AAVE speaker

listeners).5

These findings suggest that, in general, ethnographers of African American life

are giving short shrift to AAVE and its representation in the text, and only min

imally addressing transcription of participants' language. The exclusion of such

discussions calls into question the researcher's competency as a cultural and lin

guistic translator, creating a lack of transparency in authors' decisions. We turn

now to discussions of several of the reviewed ethnographies, which were analyzed

Table I. Treatment of language in African American ethnographies.

Discussion of writing respondents' speech 16% (5)

Special section devoted to language 6% (2)

Author identifies as African-American 37.5% (12)

Author identifies as white 31% (10)

Source: Book-length ethnographies of African Americans reviewed in American

Journal of Sociology, 1999-2009 (N = 32). The remaining three book-length eth

nographies from the sample did not include any mention of the categories in the

table.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 215

in depth, in order to illustrate s

divides.

Clearing up the language pro

Mary Pattillo-McCoy's book, B

Black Middle Class (2000), vivid

neighborhood she calls 'Grovela

three years. The author, herself

lives in many ways, yet maintai

discusses. Toward the beginnin

half describing how she writes

the footnotes discussing the cl

Vernacular English (2000: 230-

class black participants' use of

English and Black English d

addresses the issue of languag

senting participants' speech by

scholarly literature.

Throughout the book, Pattill

and how code-switching (one's

English) allows Groveland resid

ized by Standard English and

author is clear about how she w

My practice in rendering field not

fillers (e.g. W, 'y°u know'), as

in speech. I do try to re-create

contractions and notations that

sound (e.g. 'sayin' for 'saying', '

English into Standard English (P

Pattillo-McCoy provides ex

depended on the interactional

AAVE with her participants,

more about how she felt her

study. One section of the bo

language is important for uni

She gives an example of how her

in their community and how th

selves (Pattillo-McCoy 2000: 9

to show how language divides ar

blacks inhabit, even African A

(Pattillo-McCoy 2000: 9). The p

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

216 Ethnography 15(2)

related to her findings. This

linguistic boundaries in eve

the sociolinguistic literatur

regarding transcribing part

Translation and transcrip

In sociologist Loïc Wacquan

Boxer (2003), multiple lang

dialogue take place, some o

research site is a Chicago b

ticipants, thus presenting h

pant observation and autoet

interviews in English. Parti

presented as speaking AAV

examined, Wacquant (2003:

to the discussion of how he

Labov's and Abrahams' wor

if he were artificially conver

Wacquant acknowledges th

over time, although he admit

complicates this note-takin

of his skills, is the differenc

versus taking direct notes. Th

AAVE in real time as he woul

which dialogue comes from

added after the fact and fr

in French, Wacquant's nativ

the French version of the b

translated for the French ver

or nonstandardized characte

language conversion were e

English version. How is par

readers? French syntax is dif

the author remedy such dis

ations of text and language m

cultural translator within the social sciences.

Throughout the English version of the book, Wacquant (who speaks fluent

English with a French accent) does not phonetically transcribe his own speech in

the way that he does that of his African American participants. For example, he

transcribes one participant saying during a training session, 'Com'on, one mo', one

mo'... ' (Wacquant 2003: 66). While this is what Wacquant heard, he does not

follow the AAVE standard, which would maintain the silent 'e' in written form on

the word 'come'. This is not a syntax or grammar issue, but rather an unnecessary

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 217

non-standardized transcripti

then, that Wacquant would

accent, maintaining the pho

does not do this. By includin

story being told, the author e

leged position as a writer of

Occasionally, Wacquant prese

legitimacy as an AAVE 'insider

himself as both the privileg

raphers tend to study, and thu

read as lacking humility when

ence between them and their

In their co-authored book An

and sociologist Pierre Bourdi

being represented by the dom

researcher, as potentially ha

ital that is fraught with colon

complexities of such vernacu

privileged researcher and the

such as Standard English) a

English. Yet how can a distinct

syntax, grammar, and seman

how do AAVE semantics, gra

made aware of the back-and-

'reality' being presented in an

out reflexive consciousness a

of language to one or two pa

the ethnographies we exami

trained or expected to addres

Speaking of the American

Another example of minimal

Fall of a Modern Ghetto by

demolition and evacuation

Chicago. Venkatesh spent ye

personnel, community leader

American, yet the reader le

AAVE in the book. In the in

that must be carefully heard

tilled with rigor and then m

this capacity to represent the

tages of ethnographic metho

ously. In the human voices h

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

218 Ethnography 15(2)

narratives, language was used

South Asian-American and gr

not a long-time resident of

his positionality as it relate

Linguistic differences duri

inclusion might have further

and added to the study's ri

discussion of representing re

larger social context of the s

tics and AAVE. This neglec

words and grammatical struc

grasp of his position/location

how the ethnographer positio

the data/evidence. The read

occurring between research

ticipants' vocabulary (i.e. 'ju

ing') are read as class and iden

the mechanics of the autho

does a disservice to the resear

devalued language (AAVE),

guage should be read. It woul

chose to write his narratives

or translated his own speech,

Presenting the 'other Blac

William W. Falk's book, Roo

Community (2004), present

male researcher who lived

depictthe life of African Am

family's story of living in

then visited for several years

the book using a dedicate

Language'. While minimal,

a dialect known as Gullah

Georgia) that is familiar to h

site, Colonial County. He di

effort to 'allow the reader

acknowledges to the reader

slightly further, Falk describ

Ί have not quoted "uhs" and

truly pensive moments' (20

important to the story being

this is important beyond th

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Alose Rrown and Casanova 219

One of the pitfalls of Falk's lan

describing how Gullah or Geeche

varied Caribbean and African

raphers, we were left wondering

ing Gullah were seen by Falk a

book and could have been addr

explaining how culture influen

The representation of partic

appear to be consistent, which

when transcribing patois or AAV

shows more consistency with St

not always the case, especially

family. In fact, Falk spends m

Southerner (although not nati

the study's demographics at th

guage in which he chose to pr

placed in a subordinated positio

of in-depth explanation of th

generation.

The 'so what?' question

Why should ethnographic rese

explain their decisions about

texts? Our claims in this arti

widely-read ethnographic writin

tice, not simply generating a ne

calls for awareness have been

anthropology. We can think of

does it matter?': one we have d

inadequate or tangential, and t

these final explanations relate to

First, there are ethical (and s

writing about language in the

have more power and status th

propped up by the privileging o

Because US researchers belong

by virtue of their use of acade

represent language minorities'

hierarchies at play. We have mad

also has been made elsewhere:

with the power dynamics betwe

to study 'down', focusing on

about differences in language i

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

220 Ethnography 15(2)

in gender, race, or class; yet

We are calling for greater

guage of 'other' groups. That

embellish, or 'clean up' the

other stigmatized language

fieldwork context and its rep

potential consequences of t

ficult and worth tackling.

Second, the question of w

tension in intellectual deba

ethnographic practice and

1997; Gubrium and Holstei

related to this debate delve

able from individuals' perc

single event or moment, a

experience. A possible answ

of the links between langu

and whether an objective s

We could go back to the me

beginning with Geertz's cla

structions of other people's c

to' (2001 [1973]: 59-60). How

sentation of language in eth

transparency in such repre

our argument (that langua

whether a focus on represen

retreat from reality. Our

turned up practical problem

a lack of clarity about how la

tactics, such as altering spelli

did not produce a differen

practice, rather than a fres

its participants. The author

reality exists -that is, these

to language as a constituting

tions related to the practice

tions of (subjective or objec

A third reason for ethnogr

do with the unique contribut

especially good at giving v

often, as mentioned above, m

(1997) might call one of the c

topics, or questions pursued i

show the people and their p

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 221

ascribe to aspects of their ever

quotes from individual particip

Pattillo-McCoy's final chapters of Black Picket Fences or the afterword of

Duneier's Sidewalk (written by a key informant). In most works of ethnography,

though, participants' voices are captured in interviews and conversations held in

the field. Part of getting it right means accurately representing these voices, and

more broadly, being thoughtful about how speech is presented textually. Since

capturing the voices of participants in natural social settings is a major advantage

of ethnographic methods, and an irreplaceable contribution to our understanding

of society, part of doing good research is explaining how these voices were captured

and (if applicable) manipulated as they were placed into a text written primarily in

Standard English. Another part of doing good research involves consciously avoid

ing romanticization or exoticization of these voices and the language they use.

Writers of ethnographic texts are already making these decisions, but they are

doing so without informing the reader about how they are handling the presenta

tion of people's voices. If one of the primary things that ethnography is good for is

giving voice, then we should be responsible for describing that process in detail,

especially when we are not linguistic insiders in the communities we study.

Fourth, attention to language (not just in the sense of awareness, but in an

explicit discussion in the final text of how speech is represented) increases the

rigor of ethnographic practice. Because of the nature of participant observation,

which involves what Geertz (1998) unforgettably referred to as 'deep hanging out',

ethnographers are sometimes suspected by others in the social science community

as not being particularly rigorous in their research process. The written interpret

ations that ethnographers produce bear similarities to journalistic writing and even

fiction (a fact that the debates over realism and representation discussed above

serve to highlight). Social scientists with a more positivist orientation sometimes

look askance at ethnography, evaluating it according to standards of quantitative

research (Becker 2001 [1996]). Ethnographers thus often have an uphill battle in

terms of explaining their values of 'accuracy and precision and breadth' (Becker

2001 [1996]: 329) and defending ethnography as a rigorous method of inquiry

applicable in many academic disciplines. If sloppy writing reflects sloppy thinking,

then forgetting to mention language - despite its intrinsic and well-documented

links to individual identity and social status - can draw criticism from outside the

ethnographic community, and rightly so. Getting the details right in written reports

of fieldwork is what allows readers to trust us as authors (and authorities), and

helps buttress our claims to veracity and accuracy. If we translate our participants'

language, and have good (logical and ethical) reasons for doing so, then we should

be up-front about it. If we don't manipulate that language, we should still explain

how the spoken word is represented textually and describe the significance of lan

guage divides - including those between researcher and researched - in our research

settings. While some might criticize linguistic reflexivity of the type we are calling

for as over-the-top, an added burden on the researcher, or something that

will make ethnographic writing less accessible for non-specialists, we disagree.9

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

222 Ethnography 15(2)

Even including a few sentenc

ethnographic texts would be an

neglect linguistic matters entir

fieldwork and writing will he

research methods within the

tends to be marginalized; for

in the American Journal of

graphic books.)

Together, the third and four

stress that greater inclusion of

regard to linguistic represent

underlining its commitment

not talking about language in t

ethnographic research. We are

graphic practices related to

representing verbal commun

Incorporating linguistic awar

of everyday language and its

will help legitimize ethnograph

palpable language divides (esp

and alter or translate particip

ize the legitimacy of the ethno

kers and leave ourselves open

scientists, and participants th

rigor of the research process

onstrates the truth of our ac

argument for the practice of e

voice and rigor.

Moving forward

Language matters because it

categories that maintain soci

and writing across linguistic

inequality and have choices, a

lisher, about how to present t

and 'less than'. In searching

typically deal with linguistic d

participants, we focused on eth

United States. There was a div

same national language as eth

research subjects' language in

sion fraught with ethical, tec

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 223

Less than 16 percent of the aut

acknowledged the significance o

This means that, in most cases,

decision not to translate, but

representation of the language

researchers whose texts demo

axes of difference, such as gend

Of course, most ethnographers

not this concern appears in the

or her salt has obsessed over

language of the informants]

challenge exists even in cultu

linguistic boundaries, and intr

Standard English. By placing

aiming for greater transparen

some of these power dynamics

accurate or useful our translatio

voice and demonstrate rigor.

Ethnographers should be cau

academic public without a cri

is being said by participants, an

of sociolinguistic analysis. Oth

researcher is committing wh

the participants who have lim

research has shown that langu

communities where many Afr

died by urban ethnographers,

et al. 2001; Mahiri 2004). Without a concrete explanation of AAVE use as it

occurs, readers of such work miss out on understanding the development of com

munity through language as a cultural code. AAVE language is constructed within

the framework of the researcher's and (imagined) reader's own language, which is

typically presented as Standard English or what some scholars call White English,

and is thus also a racialized language (Chun 2001). This conventional framing of

language blurs the line between the reader's sense of participants' linguistic per

formance and linguistic competence, further creating a racialized or classed 'other'.

The work of translation and transcription was generally made invisible in the final

text. This invisibility leads to questions about the representation of the language of

research subjects, many of whom are members of vulnerable or oppressed groups.

We are not suggesting that ethnographers begin writing about the intricate

lexicon and syntax of every translated encounter, since that would clearly misplace

sociologists and social/cultural anthropologists in the discipline of linguistics.

We are arguing that for a majority of social scientists whose research crosses lin

guistic boundaries, to simply write without any mention of the literature, theory

and insights of sociolinguistics can be limiting for both the analysis and the reader.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

224 Ethnography 15(2)

It can jeopardize the rigor of

voices of the people we repre

discuss what methods are us

significantly different from

open to allowing for such ana

methods of transcription and

reading. In addition, we feel

ning of the ethnographic text,

While there are various conv

ing references to the existing

and lay bare the process of cul

should also acknowledge the

demic) Standard English, whi

the US (Ortiz 2009). The reco

onstrate the researcher's awar

both between and within cultu

of ethnographic practice. Ma

raphy and exacerbated in rese

to more in-depth analyses of h

boundaries or bridges among themselves, or between themselves and the

researcher.

It is also important to note that at least some of the exclusion of issues of

language by ethnographers may be due to the constraints placed on authors by

the publishing industry. As Cicourel writes, 'practical aspects of personal, career,

and interpersonal conditions demand that we do not dwell on reflexive thoughts

indefinitely despite our concern with how they can affect the success of research and

our careers' (Cicourel 2003: 372). The institutional and market demands of pub

lishing can place specific limitations on how one writes up, translates, or transcribes

their data. For example, publishers may not allow for a glossary of terms or

detailed discussion of translation methods, or seek to avoid excessive technical

detail for books aimed at a non-academic audience. There are also book-length

limitations that the publisher places on the author, which we and many of our

colleagues have experienced firsthand. With that said, however, authors could dis

cuss with their editors the value of considering language as part of the larger ana

lysis of the social group, rather than succumbing to the trade-off of ignoring it

completely to meet the publisher's demands.

Future research could focus on this plight by interviewing ethnographic authors

to discover what publishing constraints, if any, have impacted their research as it is

presented to a larger audience. In addition, ethnographers could interview each

other to learn about power dynamics and language representation in their work,

from the field to the writing process. Why not talk to each other about this seem

ingly taboo topic? Lastly, ethnographers may consider the effects of using profes

sional transcription services. While many ethnographers claim that they themselves

transcribe all of their fieldwork, it is common to use professional services and

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 225

graduate students or research

services impact the issue of p

transcribed in Standard Engl

reflect non-standard English, or

ist to transcribe AAVE in a p

interpreter or a 'native speake

of other languages), how does

interpreter is used? How does t

lation? These are questions th

raphy, thereby creating a more

language and even the specifi

opportunity for the training of

another based on observation, o

them up, and then compare the

conversation of how one re

another's, and may reveal ho

the participants' voice, but als

As ethnographers, we (the au

our work, and after surveying

participants' language, we are

language. When we neglect th

and communities of those wh

choose to write participants' w

privilege based on class, race,

more linguistic reflexivity in

2007; Hanks 2005), yet that ca

guage difference and representa

rigorous linguistic reflexivity

voices, is one path to more fu

dynamics at play in ethnograp

Acknowledgements

We are especially grateful to Ph

Jooyoung Lee, and Gregory Smith

this article. We are indebted to A

Thanks also to the audience of a

this article were initially presented

for their substantive comments.

Notes

1. Linguistic anthropologist Michael Agar has insightfully compared the entire e

graphic research process to learning a second language (Agar 2008); the similar

especially marked for those conducting research across divides of language.

2. 'Native speaker' is a contested term that we discuss later.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

226 Ethnography 15(2)

3. Recently, we have drawn atte

researcher-subject relations in

2009). Here we extend upon the

by suggesting that the logic be

incorporated into the written te

4. We had originally hoped to in

journal of the American Anthr

ciplinary method of inquiry sh

However, there were no book-l

American Anthropologist during

international orientation of anth

urban ethnography to sociologi

5. We also conducted content an

reviews published from 1999-2

(Masi de Casanova and Mose Brown, manuscript in progress; Masi de Casanova,

2010). This complementary analysis also found minimal attention to language and lin

guistic boundaries in English-language books based on fieldwork in Spanish-speaking,

Portuguese-speaking, and other non-English contexts, despite the fact that many of the

authors were anthropologists. We see this as an important comparison case, since these

studies cross divides between languages rather than within a single language. The findings

show that even these more pronounced linguistic differences between the language of

participants and the language of the final text are not addressed by authors.

6. Pattillo-McCoy uses the term Black English, which is synonymous with AAVE.

7. For an example of this pronunciation, video recordings of his presentations show how the

English word 'the' becomes 'de' for Wacquant (YouTube, accessed 18 March 2010).

8. It should be noted that Venkatesh does reflect on the topic of his position vis-à-vis the

research participants in more recent works that were not in our sample.

9. Kasinitz (2011: 950), for example, complained of the 'self-reflexive paralysis that

ensnared many talented researchers in recent years'. He is certainly not the only scholar

to worry about ethnographers becoming 'imprisoned' by reflexive concerns.

References

Abrahams R (1962) Playing the dozens. Journal of American Folklore 75: 209-20.

Abrahams R (1972) Stereotyping and beyond. In: Abrahams RD and Troike RC

Language and Cultural Diversity in American Education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pre

Hall, pp. 19-29.

Agar M (2008) A linguistics for ethnography. Journal of Inter cultural Communication

Alim SH, Ibrahim A and Pennycook A (2009) Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultu

Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language. New York: Routledge.

Atkinson Ρ (1990) The Ethnographic Imagination. New York: Routledge.

Baca Zinn M (1979) Field research in minority communities: Ethical, methodological

political observations from an insider. Social Problems 27(2): 209-219.

Bailey G (2001) The relationship between African-American Vernacular English and w

vernaculars in the American South. In: Lanehart S (ed.) African American English:

of the Art. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 53-92.

Baugh J (1983) Black Street Speech: Its History, Structure, and Survival. Austin: Univer

of Texas Press.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 227

Baugh J (1999) Out of the Mouths

Malpractice. Austin: University of

Becker HS (2001 [1996]) The episte

Contemporary Field Research: Per

Waveland Press, pp. 317-330.

Benjamin W (2000 [1923]) Task of

Baudelaire's Tableaux Parisiens,

Studies Reader. New York: Routle

Bourdieu Ρ and Wacquant L (199

University of Chicago Press.

Chun Ε (2001) The construction of

African American Vernacular Engl

Churchill Jr CJ (2005) Ethnograph

Cicourel AV (1980) Language and s

Sociological Inquiry 50(3/4): 1-30.

Cicourel AV (2003) On contextualizi

Linguistics 24(3): 360-373.

Clifford J (1997) Routes: Travel and

MA: Harvard University Press.

Clough PT (1998) The End(s) of Eth

Peter Lang.

Cutler C (2003) 'Keepin' it real': White hip-hoppers' discourses of language, race, and

authenticity. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 13(2): 211-233.

Davies A (2003) The Native Speaker: Myth and Reality. Trowbridge: Cromwell Press Ltd.

Davies Ρ and Mehan Η (2007) Aaron Cicourel's contributions to language use, theory,

method, and measurement. Text and Talk 27(5/6): 595-610.

Dayton Ε (1996) Grammatical categories of the verb in African-American Vernacular

English. PhD Thesis, University of Pennsylvania. Available at: http://reposi

tory.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI9712915.

Denzin NK (1997) Interpretive Ethnography: Ethnographic Practices for the 21st Century.

Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Devault M (1999) Liberating Method: Feminism and Social Research. Philadelphia: Temple

University Press.

Duneier M (1991) Sidewalk. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Dyson AH (2003) The Brothers and Sisters Learn to Write: Popular Literacies in Childhood

and School Cultures. New York: Teachers College Press.

Falk WW (2004) Rooted in Place: Family and Belonging in a Southern Black Community.

Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Fordham S (1999) Dissin' 'the Standard': Ebonics as guerrilla warfare at Capital High.

Anthropology & Education Quarterly 30(3): 272-293.

Gee JP, Allen A and Clinton Κ (2001) Language, class, and identity: Teenagers fashioning

themselves through language. Linguistics and Education 12(2): 175-194.

Geertz C (1998) Deep hanging out. New York Times Review of Books, 22 October. Available

at: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1998/oct/22/deep-hanging-out/.

Geertz C (2001 [1973]) Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture.

In: Emerson RM (ed.) Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations,

2nd edn. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, pp. 55-75.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

228 Ethnography 15(2)

Gubrium JF and Holstein J A

Oxford University Press.

Gumperz J (1968) The speech

A Reader. Cambridge: Cambr

Gutiérrez Rodriguez Ε (2006) T

transversal understanding. I

Project·. Under Translation, J

sal/0606/gutierrez-rodriguez/e

Hammersley M (1992) What's W

York: Routledge.

Hanks WF (2005) Pierre Bou

Anthropology 34: 67-83.

Heath SB (1978) Social history

84-92.

Jacobs-Huey L (2002) The natives are gazing and talking back: Reviewing the problematics

of positionality, voice, and accountability among 'native' anthropologists. American

Anthropologist 104(3): 791-804.

Kasinitz Ρ (2011) The best of (ethnographic) times is now. Sociological Forum 26(4):

950-951.

Katz J (1997) Ethnography's warrants. Sociological Methods and Research 25(4): 391—423.

Kirkland D and Jackson A (2008) Beyond the silence: Instructional approaches and stu

dents' attitudes. In: Scott J, Straker DY and Katz L (eds) Affirming Students' Right to

Their Own Language: Bridging Educational Policies and Language I Language Arts

Teaching Practices. Champagne/Urbana, IL: NCTE/LEA, pp. 136-154.

Kirkland DE and Jackson A (2009) 'We real cool': Τ ο ward a theory of black masculine

literacies. Reading Research Quarterly 44(3): 278-297.

Kramsch C (1997) The privilege of the nonnative speaker. The Modern Language Association

of America 112(3): 359-369.

Labov W (1972) Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular.

Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Labov W (1982) Objectivity and commitment in linguistic science: The case of the Black

English trial in Ann Arbor. Language in Society 11: 165-202.

Labov W (1998) Co-existent systems in African-American Vernacular English. In: Mufwene

SS, Rickford JR, Bailey G and Baugh G (eds) African American English: Structure,

History, and Use. New York: Routledge, pp. 10-153.

Labov W (2001) Applying our knowledge of African American English to the problem of

raising reading levels in inner-city schools. In: Lanehar S (ed.) African American English:

State of the Art. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 299-318.

Labov W (2010) Unendangered dialect, endangered people: The case of African American

Vernacular English. Transforming Anthropology 18(1): 15-28.

Medgyes Ρ (2001) When the teacher is a non-native speaker. In: Celce-Murcia M (ed.)

Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language. Boston: Heinle & Heinle, pp. 429—442.

Mahiri J (ed.) (2004) What They Don't Learn in School: Literacy in the Lives of Urban Youth.

New York: Peter Lang.

Masi de Casanova Ε (2010) Ethnographic border crossings: Translating Latin American

lives. Presentation given at the Eastern Sociological Society Annual Meeting, Boston,

MA.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 229

Masi de Casanova Ε and Mose Br

tion, translation in ethnograph

Merton RK (1972) Insiders an

American Journal of Sociology

Mose Brown Τ and Masi de Cas

shapes fieldwork and research

42-57.

Mufwene SS, Rickford JR. Bailey G and Baugh J (eds) (1998) African American English:

Structure, History, and Use. New York: Routledge.

Ortiz R (2009) La Supremacia del Inglés en las ciencias sociales. Buenos Aires: Siglo

Veintiuno Editores.

Paikeday TM (2003) The Native Speaker is Dead! Brampton, ON: Lexicography Inc.

Paris D (2009) They're in my culture, they speak the same way': African American language

in multiethnic high schools. Harvard Educational Review 79(3): 428-447.

Pattillo-McCoy M (2000) Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril among the Black Middle

Class. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Piller I (2002) Passing for a native speaker: Identity and success in second language learning.

Journal of Sociolinguistics 6(2): 179-206.

Roberts JT and Harden Τ (1997) Native or non-native speakers teachers of foreign lan

guages? Old and new perspectives on the debate. The Irish Yearbook of Applied

Linguistics 17: 1-28.

Sadovnik AR (2001) Profiles of famous educators: Basil Bernstein (1924-2000). Prospects

31(4): 607-620.

Spears A (1982) The Black English semi-auxiliary come. Language 58(4): 850-872.

Venkatesh SA (2002) American Project: The Rise and Fall of a Modern Ghetto. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Wacquant L (2000) Corps et âme: Canets ethnographiques d'un apprenti boxeur. Marseilles

and Montreal: Agone, Comeau & Nadeau.

Wacquant L (2003) Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Whorf BL (1987) Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf

ed. Carroll JB. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Author Biographies

Tamara Mose Brown is Assistant Professor of Sociology and Program Director of

Caribbean Studies at Brooklyn College, CUNY. She is author of Raising Brooklyn:

Nannies, Childcare, and Caribbeans Creating Community (NYU Press, 2011).

Erynn Masi de Casanova is Assistant Professor of Sociology and Faculty Affiliate

of the Departments of Romance Languages and Literatures and Women's,

Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Cincinnati. She is author of

Making Up the Difference: Women, Beauty, and Direct Selling in Ecuador

(University of Texas Press, 2011).

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

230 Ethnography 15(2)

U.S. Region

€0

■■

EastEast

Coast: 33%Coast: 33%

■■

Midwest:

Midwest:

34% 34%

■■

South:

South:

13% 13%

■West Coast: 20%

Appendix I. Ethnographies of African Americans by region of the US.

Appendix 2

African American ethnographies: reviewed in American Journal

of Sociology, 1999-2009

Anderson Ε (1999) Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the

Inner City. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Anyon J (1997) Ghetto Schooling: A Political Economics of Urban Education

Reform. New York: Teachers College Press.

Banks I (2000) Hair Matters: Beauty, Power and Black Women's Consciousness.

New York: New York University Press.

Bartkowski JP and Regis HA (2003) Charitable Choices: Religion, Race, and

Poverty in the Post-Welfare Era. New York: New York University Press.

Buford May RA (2001) Talking at Trena's: Everyday Conversations at an

African American Tavern. New York: New York University Press.

Buford May RA (2008) Living through the Hoop: High School Basketball, Race,

and the American Dream. New York: New York University Press.

Chetkovich C (1997) Real Heat: Gender and Race in the Urban Fire Service. New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Cohen CJ (1999) Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS & the Breakdown of Black

Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Duneier M (1999) Sidewalk. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Falk WW (2004) Rooted in Place: Family and Belonging in a Southern Black

Community. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Ferguson AA (2000) Bad Boys: Public Schools in the Making of Black

Masculinity. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Gavanas A (2004) Fatherhood Politics in the United States: Masculinity,

Sexuality, Race and Marriage. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mose Brown and Casanova 231

Grazian D (2003) Blue Chica

Clubs. Chicago, IL: Universit

Gregory S (1998) Black Cor

Community. Princeton, NJ: Pr

Lee J (2002) Civility in the

Cambridge, MA: Harvard Un

Lewis AE (2003) Race in th

Classrooms and Communities

McRoberts OM (2003) Street

Urban Neighborhood. Chicag

Newman Κ (1999) No Shame

New York: Random House.

Owen Β (1998) 'In the Mix': Struggle and Survival in a Women's Prison. Alban

NY: State University of New York Press.

Owens ML (2007) God and Government in the Ghetto: Politics of Church-Sta

Collaboration in Black America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pattillo-McCoy M (1999) Black Picket Fences: Privilege and Peril Among th

Black Middle Class. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pattillo-McCoy M (2007) Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class

the City. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pellow DN (2002) Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in

Chicago. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rouse, CM (2004) Engaged Surrender: African American Women and Islam.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Sterk CE (1999) Fast Lives: Women Who Use Crack Cocaine. Philadelphia, P

Temple University Press.

Stockdill BC (2003) Activism against AIDS: At the Intersections of Sexualit

Race, Gender and Class. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Vale LJ (2002) Reclaiming Public Housing: A Half-Century of Struggle in Thr

Public Neighborhoods. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Venkatesh S (2000) American Project: The Rise and Fall of a Modem Ghetto

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wacquant L (2003) Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer. Oxford

Oxford University Press.

Wells AS and Crain RL (1997) Stepping Over the Color Line: African-Americ

Students in White Suburban Schools. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wright RT and Decker SH (1997) Armed Robbers in Action: Stickups and Stre

Culture. Lebanon, NH: Northeastern University Press.

Young AA (2004) The Minds of Marginalized Black Men: Making Sense

Mobility, Opportunity, and Future Life Chances. Princeton, NJ: Princet

University Press.

This content downloaded from

89.215.123.18 on Thu, 07 Oct 2021 05:16:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Racing Translingualism in Composition: Toward a Race-Conscious TranslingualismFrom EverandRacing Translingualism in Composition: Toward a Race-Conscious TranslingualismTom DoNo ratings yet

- A World Within The WorldDocument170 pagesA World Within The Worldtito_pavia5811No ratings yet

- Kroskrity2021ArticulatingLingualLifeHistoriesandLanguageIdeologicalAssemblagescorrectedproof PDFDocument21 pagesKroskrity2021ArticulatingLingualLifeHistoriesandLanguageIdeologicalAssemblagescorrectedproof PDFMayra AlejandraNo ratings yet

- Ugo's WorkDocument52 pagesUgo's WorkStephen GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Marking Communicative Repertoire ThroughDocument19 pagesMarking Communicative Repertoire ThroughRAFAELNo ratings yet

- Noun Class and Number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-Historical Research and Respecting Speakers' Rights in FieldworkDocument33 pagesNoun Class and Number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-Historical Research and Respecting Speakers' Rights in FieldworkmarilutarotNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Lesson 1Document6 pagesChapter 1 Lesson 1John DeguiraNo ratings yet

- Socio Ling Vis TikaDocument12 pagesSocio Ling Vis TikaMerisaNo ratings yet

- Kerswill, "Identity, Ethnicity and Place - The Construction of Youth Language in London "Document34 pagesKerswill, "Identity, Ethnicity and Place - The Construction of Youth Language in London "Jack SidnellNo ratings yet

- Perley, Bernard (2012) Zombie Linguistics: Experts, Endangered Languages and The Curse of Undead VoicesDocument18 pagesPerley, Bernard (2012) Zombie Linguistics: Experts, Endangered Languages and The Curse of Undead Voicesalan ortegaNo ratings yet

- Arabic SociolinguisticsDocument52 pagesArabic SociolinguisticsthakooriNo ratings yet

- LANGUAGEDIVERSITYANDLANGUAGECHANGEININDONESIA Goebel ForpublicdisseminationDocument29 pagesLANGUAGEDIVERSITYANDLANGUAGECHANGEININDONESIA Goebel Forpublicdisseminationiqbal hazairinNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Society of AmericaDocument43 pagesLinguistic Society of AmericadiegoNo ratings yet

- Sign Languages in The WorldDocument29 pagesSign Languages in The Worldtheycallme_lanaNo ratings yet

- Dakota and Ojibwe English SlangDocument18 pagesDakota and Ojibwe English Slangmwvaughn19No ratings yet

- Chapter 07 Language and SocietyDocument12 pagesChapter 07 Language and SocietyButch PicardalNo ratings yet

- Sociolgtcs L3Document13 pagesSociolgtcs L3constantkone1999No ratings yet

- Sapir (1929) Status of Linguistics As A ScienceDocument9 pagesSapir (1929) Status of Linguistics As A ScienceHarryNo ratings yet

- Environmental Degradation 1s Degradation in Language and CultureDocument9 pagesEnvironmental Degradation 1s Degradation in Language and CultureDragosGeorgei7No ratings yet

- Linguistic Repertoire and Ethnic Identity in New York CityDocument12 pagesLinguistic Repertoire and Ethnic Identity in New York CityAurora TsaiNo ratings yet

- Language Change and Development Historical LinguisDocument15 pagesLanguage Change and Development Historical LinguisJean BalaticoNo ratings yet

- Why and How The Translator Constantly Makes Decisions About Cultural MeaningDocument8 pagesWhy and How The Translator Constantly Makes Decisions About Cultural MeaningGlittering FlowerNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 193.145.118.251 On Wed, 15 Feb 2023 12:57:04 UTCDocument4 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 193.145.118.251 On Wed, 15 Feb 2023 12:57:04 UTCMaría GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Ethnicity and CultureDocument4 pagesEthnicity and Culturedafher1No ratings yet

- Grinevald & Sinha 2020Document21 pagesGrinevald & Sinha 2020thatypradoNo ratings yet

- Critical Annalysis of Ngugi Wa Thiongo NovelsDocument8 pagesCritical Annalysis of Ngugi Wa Thiongo NovelsBosire keNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2. Dynamic Models of Language Evolution: The Linguistic PerspectiveDocument49 pagesChapter 2. Dynamic Models of Language Evolution: The Linguistic PerspectiveJana AtraNo ratings yet

- Strong and Weak Dialects of China How Cantonese SuDocument15 pagesStrong and Weak Dialects of China How Cantonese SuГерман НедовесовNo ratings yet

- North INd Dialect and Social StratificationDocument16 pagesNorth INd Dialect and Social StratificationSchuyler HeinnNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistics Mid TermDocument49 pagesSociolinguistics Mid TermUmmama Bhutta100% (1)

- Varieties of EnglishDocument66 pagesVarieties of Englishlorelai.godinovNo ratings yet

- An Historical Perspective On Contemporary LinguistDocument5 pagesAn Historical Perspective On Contemporary LinguistAnne AlencarNo ratings yet

- Pidgin and Creole Languages: March 2015Document15 pagesPidgin and Creole Languages: March 2015RAKOTOMALALANo ratings yet

- Reviewer Bsee22Document5 pagesReviewer Bsee22joannachelcalayag.10No ratings yet

- Deaf Translators What Are They ThinkingDocument23 pagesDeaf Translators What Are They ThinkingKarolina WojciechowskaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Evolution of Ethiopic Languages: A Comparative DiscussionDocument10 pagesLinguistic Evolution of Ethiopic Languages: A Comparative DiscussionDaniel WimanNo ratings yet

- Language VariationDocument2 pagesLanguage Variationakochiwakal7No ratings yet

- Bilingualism and Diglossia Patterns of Language UsDocument13 pagesBilingualism and Diglossia Patterns of Language UsSirine SirineNo ratings yet

- The Sapir Whorf Hypothesis Analysis of LDocument5 pagesThe Sapir Whorf Hypothesis Analysis of LWasle YarNo ratings yet

- A Critique of Language Languaging and SupervernacuDocument12 pagesA Critique of Language Languaging and SupervernacuNino PirtskhalavaNo ratings yet

- Critical Antiracist Pedagogy in ELTDocument10 pagesCritical Antiracist Pedagogy in ELTNUR MARLIZA RAHMI AFDINILLAH Pendidikan Bahasa InggrisNo ratings yet

- World Englishes Social DisharmonisationDocument18 pagesWorld Englishes Social DisharmonisationDarcknyPusodNo ratings yet

- Paper Cross Culture UnderstandingDocument14 pagesPaper Cross Culture UnderstandingAni SyafiraNo ratings yet

- Embodiment Linguistics Space American Sign Language Meets GeographyDocument19 pagesEmbodiment Linguistics Space American Sign Language Meets GeographyRadamir SousaNo ratings yet

- MAED ReferencingDocument4 pagesMAED ReferencingRosie LangotanNo ratings yet

- Vaughan Singer 2018Document8 pagesVaughan Singer 2018Rosana RogeriNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Linguistic Forms and Functions: I. I The Functions of LanguageDocument27 pagesIntroduction: Linguistic Forms and Functions: I. I The Functions of LanguageMuhammad SufyanNo ratings yet

- Endangerment of LanguageDocument39 pagesEndangerment of LanguageRendel RosaliaNo ratings yet

- 300 S 20 Syllabus (2) 4Document13 pages300 S 20 Syllabus (2) 4jesseNo ratings yet

- Language and Religion As Key Markers of EthnicityDocument12 pagesLanguage and Religion As Key Markers of EthnicityTrishala SweenarainNo ratings yet

- Word English'sDocument7 pagesWord English'sAhsanul AmriNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - Ethnolinguistics - PPTDocument26 pagesLecture 6 - Ethnolinguistics - PPTМарина ТаргонскаяNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistics and Language VariationDocument5 pagesSociolinguistics and Language VariationThe hope100% (1)

- Geneal Linguistics ArticleDocument12 pagesGeneal Linguistics ArticleNoureen FatimaNo ratings yet

- Why Some Behaviors Spread While Others DDocument14 pagesWhy Some Behaviors Spread While Others DlalatsulalatNo ratings yet

- Risya Dwi Ashilah - Valid UAS CR ABC 2021-2022Document5 pagesRisya Dwi Ashilah - Valid UAS CR ABC 2021-2022Risya dwi ashilahNo ratings yet

- A Comprehensive Indonesian-English DictionaryDocument24 pagesA Comprehensive Indonesian-English DictionarychantalNo ratings yet

- Language and SocietyDocument37 pagesLanguage and SocietyyaniNo ratings yet

- Joflinguisticanthropology 2007Document26 pagesJoflinguisticanthropology 2007NunggeannuNo ratings yet

- Toward Translingual Realities in Composition: (Re)Working Local Language Representations and PracticesFrom EverandToward Translingual Realities in Composition: (Re)Working Local Language Representations and PracticesNo ratings yet

- Saunders Research OnionDocument24 pagesSaunders Research OnionZabih UllahNo ratings yet

- Microfinance and Women's Empowerment in Bangladesh: Unpacking The Untold NarrativesDocument134 pagesMicrofinance and Women's Empowerment in Bangladesh: Unpacking The Untold NarrativesMehadi Al Mahmud0% (1)

- 36 Negotiating Public SpacesDocument189 pages36 Negotiating Public Spacesmey1skanderNo ratings yet

- On Being Critical in Health and Physical EducationDocument17 pagesOn Being Critical in Health and Physical Educationandres OnrubiaNo ratings yet

- Etnographic Field Methods and Their Relation To DesignDocument9 pagesEtnographic Field Methods and Their Relation To DesignmarcorossNo ratings yet

- Bainbridge 2003 (The Future in The Social Science) PDFDocument18 pagesBainbridge 2003 (The Future in The Social Science) PDFHebe Signorini GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Witherspoon NavajoINTDocument18 pagesWitherspoon NavajoINTGuilherme WerlangNo ratings yet

- HhfyDocument21 pagesHhfyWinard PalcatNo ratings yet

- Auger Et Al 1987Document316 pagesAuger Et Al 1987Américo H Santillán CNo ratings yet

- RSCH G11 AnswerkeyDocument19 pagesRSCH G11 AnswerkeyCharlote Mirikashitamochiku Echiverri WP100% (3)

- CS408 MidTerm Subjective Reference FileDocument16 pagesCS408 MidTerm Subjective Reference FileQuratulain KanwalNo ratings yet

- The Axtell Family Letters: Discursive Constructions of Self and Society at Fort Brooke, Tampa, Florida, 1844-1850Document23 pagesThe Axtell Family Letters: Discursive Constructions of Self and Society at Fort Brooke, Tampa, Florida, 1844-1850Brian A. SalmonsNo ratings yet

- Community Mapping Is A Term Used To Describe Both A "Process and A Product"Document2 pagesCommunity Mapping Is A Term Used To Describe Both A "Process and A Product"Vladimer Desuyo PionillaNo ratings yet

- Hall 1999 PerformativityDocument5 pagesHall 1999 PerformativityMwami JoseNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Wallach-Modern Noise, Fluid Genres - Popular Music in Indonesia, 1997-2001 (New Perspectives in Se Asian Studies) PDFDocument346 pagesJeremy Wallach-Modern Noise, Fluid Genres - Popular Music in Indonesia, 1997-2001 (New Perspectives in Se Asian Studies) PDFAlmer SidqiNo ratings yet

- Varieties of Qualitative Research A Pragmatic Approach To Selecting MethodsDocument14 pagesVarieties of Qualitative Research A Pragmatic Approach To Selecting MethodsEllen Figueira100% (4)

- Introduction Handbook Gathers and HuntersDocument23 pagesIntroduction Handbook Gathers and HuntersCamila LunaNo ratings yet

- Shumar2013 - Ethnography in A Virtual WorldDocument19 pagesShumar2013 - Ethnography in A Virtual WorldHENRÍQUEZ OLIVARES MAITE SOLNo ratings yet

- Senior High SchoolDocument25 pagesSenior High SchoolLudwin Daquer100% (1)

- Ethnography in The Fiekl of DesignDocument12 pagesEthnography in The Fiekl of Designjuan carlosNo ratings yet

- Moving While Standing StillDocument12 pagesMoving While Standing Stillresistor4uNo ratings yet

- Coming Of: Margaret Mead and Samoa: in Fact and FictionDocument8 pagesComing Of: Margaret Mead and Samoa: in Fact and FictionFacundo GuadagnoNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Researc1.Docx PreDocument13 pagesQualitative Researc1.Docx PreSalah KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Max Bondi Things of Africa Rethinking Candomblé in BrazilDocument22 pagesMax Bondi Things of Africa Rethinking Candomblé in BrazilOlavo SouzaNo ratings yet

- Adeyinka Wulemat Olarinmoye - The Images of Women in Yoruban Folktales PDFDocument12 pagesAdeyinka Wulemat Olarinmoye - The Images of Women in Yoruban Folktales PDFAngel SánchezNo ratings yet

- Research DesignDocument61 pagesResearch DesignJamaine Jane GlovaNo ratings yet

- Pedro Pitarch & José Antonio Kelly (Eds.) - The Culture of Invention in The Americas. Anthropological Experiments With Roy Wagner-Kingston (2019)Document283 pagesPedro Pitarch & José Antonio Kelly (Eds.) - The Culture of Invention in The Americas. Anthropological Experiments With Roy Wagner-Kingston (2019)Jozzh D-pepperlandNo ratings yet

- Feld Doing Anthropology in SoundDocument15 pagesFeld Doing Anthropology in SoundIvoz ZabaletaNo ratings yet

- In-Depth Interviews & EthnographyDocument29 pagesIn-Depth Interviews & EthnographyJin ZuanNo ratings yet