Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Simhan Et Al. - Nephron-Sparing Vs Radical NPU For Upper Tract Urothelial TCC

Uploaded by

yuenkeithOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Simhan Et Al. - Nephron-Sparing Vs Radical NPU For Upper Tract Urothelial TCC

Uploaded by

yuenkeithCopyright:

Available Formats

Nephron-sparing management vs radical

nephroureterectomy for low- or moderate-grade,

low-stage upper tract urothelial carcinoma

Jay Simhan, Marc C. Smaldone, Brian L. Egleston*, Daniel Canter†, Steven N. Sterious,

Anthony T. Corcoran, Serge Ginzburg, Robert G. Uzzo and Alexander Kutikov

Division of Urologic Oncology, Departments of Surgical Oncology, *Biostatistics, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Temple

University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA and †Department of Urology, Emory University School of Medicine,

Atlanta, GA, USA

Objective (26.1%) patients underwent RNU and NSM for low- or

• To compare overall and cancer-specific outcomes between moderate-grade, low-stage UTUC from 1992 to 2008.

patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) • Patients undergoing NSM were older (mean age 71.6

managed with either radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) or vs 69.7 years, P < 0.01) with a greater proportion of

nephron-sparing measures (NSM) using a large well-differentiated tumours (26.3% vs 18.0%, P = 0.001).

population-based dataset. • While there were differences in OCM between the groups

(P < 0.01), CSM trends were equivalent. After adjustment,

Patients and Methods RNU treatment was associated with improved non-cancer

• Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cause survival [hazard ratio (HR) 0.78, confidence interval

data, patients diagnosed with low- or moderate-grade, [CI] 0.64–0.94) while no association with CSM was

localised non-invasive UTUC were stratified into two demonstrable (HR 0.89, CI 0.63–1.26).

groups: those treated with RNU or NSM (observation,

endoscopic ablation, or segmental ureterectomy). Conclusions

• Cancer-specific mortality (CSM) and other-cause mortality • Patients with low- or moderate-grade, low-stage UTUC

(OCM) rates were determined using cumulative incidence managed through NSM are older and are more likely to die

estimators. Adjusting for clinical and pathological of other causes, but they have similar CSM rates to those

characteristics, the associations between surgical type, patients managed with RNU.

all-cause mortality and CSM were tested using Cox • These data may be useful when counselling patients with

regressions and Fine and Gray regressions, respectively. UTUC with significant competing comorbidities.

Results Keywords

• Of 1227 patients [mean (SD) age 70.2 (11.00) years, 63.2% upper tract urothelial carcinoma, SEER, nephron-sparing

male] meeting inclusion criteria, 907 (73.9%) and 320 surgery

Introduction with the intention of achieving acceptable oncological results

[8–10].

Accounting for only 5% of all renal and urothelial tumours,

upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) is a rare While cancer staging of UTUC is commonly established with

genitourinary malignancy [1]. Although current management endoscopic biopsy at ureteropyeloscopy, inadequate tissue

guidelines for UTUC advocate radical nephroureterectomy sampling and apprehensions of ureteric perforation render

(RNU) with formal resection of the bladder cuff as a ‘gold the accurate determination of tumour stage challenging [11].

standard’ treatment [2–4], the resultant solitary kidney status As such, due to concerns about oncological control, many

may lead to higher rates of dialysis, cardiovascular morbidity, clinicians are prompted to undertake radical extirpative

and overall mortality [5–7]. In an effort to mitigate these treatment even in patients with low-stage UTUC [4]. In

attendant risks, nephron-sparing measures (NSM) have contrast, experts advocate that patients with UTUC with

been advocated in carefully selected patients with UTUC low-grade, low-stage disease may be candidates for NSM,

© 2013 The Authors

BJU Int 2014; 114: 216–220 BJU International © 2013 BJU International | doi:10.1111/bju.12341

wileyonlinelibrary.com Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. www.bjui.org

Nephron sparing vs radical nephroureterectomy for UTUC

including endoscopic ablation and segmental ureterectomy, NSM (e.g. patients not undergoing nephrectomy or RNU).

provided they accept the necessity of rigorous post-procedure Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared

surveillance [2,3,8,12,13]. between groups using ANOVA and chi-square tests. CSM and

OCM rates were determined using cumulative incidence

Contemporary studies have shown the utility of

estimators. Kaplan–Meier survival estimates were used to

individualising patient management to arrive at the optimal

describe overall survival trends and compare both groups

UTUC treatment strategy [14–16]. Although previous reports

using a log-rank test for overall survival differences. Cox

have shown that patients with low-grade, low-stage UTUC

regressions were used for assessment of all-cause mortality

have been successfully managed with NSM, documentation

(ACM) while Fine and Gray competing risks proportional

on the oncological efficacy of these non-extirpative measures

hazards regressions were used to identify independent

largely has been limited to small institutional series with

predictors of cancer-specific death. Analyses were conducted

short-term patient follow-up [8–10,17]. In the present study,

using STATA version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas),

using data from a national cancer registry, our aim was to

and R version two (The R Foundation for Statistical

compare cancer-specific and overall survival in patients

Computing, Vienna, Austria), with P < 0.05 meeting

treated with RNU and NSM for non-high grade, low-stage

considered to indicate statistical significance.

UTUC. Given limitations of establishing tumour grade and

stage in the clinical setting, these data afford an insightful

assessment of outcomes in patients who were treated with Results

non-extirpative measures for UTUC.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the 1227 patients

[mean (SD) age 70.2 (11.0) years, 63.2% male) meeting

Patients and Methods inclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. Of the patients,

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 26.1% (320 patients, 65.6% male) underwent conservative

data, we identified all patients diagnosed with UTUC (codes management (62.5% segmental ureterectomy and 37.5%

C65.9 and C66.9) from 1992 to 2008. The SEER registries endoscopic treatment/observation) of non-high grade,

include those active from 1992, including Alaska natives, the low-stage UTUC while 73.9% (907 patients) underwent RNU.

metropolitan areas of San Francisco-Oakland, Detroit, Seattle, Patients treated with NSM tended to be older [mean (SD)

Atlanta, San Jose-Monterey, and Los Angeles county, as well as 71.6 (10.6) vs 69.7 (11.1), P = 0.007) with a greater proportion

rural Georgia, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, and of G1 tumours (26.3% vs 18.0%, P = 0.001) than patients

Utah. The characteristics of the SEER population have treated with RNU. More patients that underwent NSM had a

been shown to be a representative sample of the general prior non-UTUC cancer diagnoses than RNU patients (68.4%

population of the USA [18]. For each person diagnosed within vs 63.8%, P < 0.001). There were no differences between

these defined geographic areas, the SEER registries collect treatment groups with respect to marital status (P = 0.90),

information of every occurrence of a primary incident cancer gender (P = 0.23), or race (P = 0.51).

including the month and year of diagnosis and cancer site,

The median (interquartile range) follow-up of all patients

stage, pathological data including stage and histology,

included in this analysis was 61 (25–111) months. The

treatment method, and vital status including cause of death

cumulative incidence of death from UTUC and OCM are

for patients who died during follow-up.

shown in Figure 1. Although patients treated with RNU were

All individuals with non-high grade, non-muscle-invasive less likely to die of other causes (P = 0.009), CSM was similar

urothelial carcinoma were identified by determining all (P = 0.36) between treatment groups. Adjusting for clinical

patients with localised disease through SEER Historic Staging and pathological characteristics, while increasing age [hazard

(American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage T1). This ratio (HR) 1.02, 95% CI 1.0–1.03, P = 0.01) and female gender

method captures all cases of localised UTUC while excluding (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.11–2.11, P = 0.01) were associated with

individuals with potentially more advanced disease observed CSM, there was no significant association with treatment type

through extent of disease codes 10 and 30. All patients with (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.63–1.26, P = 0.50). Furthermore, year

N+ and M+ disease were additionally excluded. Only patients of diagnosis (P = 0.64), marital status (P = 0.41), and race

with well-differentiated (grade 1[G1]) and moderately (P = 0.59) were not associated with CSM.

differentiated (grade 2[G2]) tumours were included. For the

Adjusting for clinical and pathological characteristics, patients

purposes of this study, deaths from UTUC were coded as

undergoing RNU were less likely (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.64–0.94,

cancer-specific mortality (CSM) while all other deaths were

P = 0.009, Table 2) to experience ACM than patients managed

considered other-cause mortality (OCM).

with NSM. Similarly, females (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–0.99,

Patients meeting inclusion criteria were stratified into two P = 0.04) and married patients (HR 0.83, 95% CI CI 0.69–0.99,

groups: those treated with RNU (pre-1998 codes 20, 30, 40, 50, p = 0.04) were less likely to die of other causes. In comparison,

60 and 1998+ codes 40, 50, 80) and those managed through older patient age (HR 1.07, 95% CI 1.06–1.08, P < 0.001), and

© 2013 The Authors

BJU International © 2013 BJU International 217

Simhan et al.

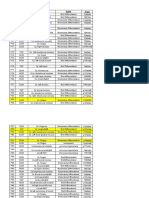

Table 1 Demographic and clinical variables for all patients with UTUC from 1992–2008 meeting

inclusion criteria.

Variable Overall NSM RNU P

Number of patients (%) 1227 320 (26.1) 907 (73.9)

Mean (SD) age, years 70.2 (11.0) 71.6 (10.6) 69.7 (11.1) 0.007

N (%):

Gender: 0.23

Male 775 (63.2) 210 (65.6) 565 (62.3)

Female 452 (36.8) 110 (34.4) 342 (37.7)

Marital status: 0.90

Married 468 (38.1) 197 (61.6) 562 (62.0)

Unmarried 759 (61.9) 123 (38.4) 345 (38.0)

Race: 0.51

White 1073 (87.5) 283 (88.4) 790 (87.1)

African-American 44 (3.6) 13 (4.1) 31 (3.4)

Other 110 (8.9) 24 (7.5) 86 (9.5)

Tumour grade: 0.001

G1 247 (20.1) 84 (26.3) 163 (18.0)

G2 980 (79.9) 236 (73.7) 744 (82.0)

NSM included endoscopic therapy, segmental ureterectomy and observation; G1, Grade 1 (well-differentiated); G2, Grade

2 (moderately differentiated).

Fig. 1 Cumulative incidence curves assessing OCM and CSM in patients Table 2 Regression analysis showing associations between patient

undergoing RNU or NSM. While patients undergoing RNU had decreased characteristics and CSM and ACM.

rates of OCM (P = 0.009) compared with NSM patients, similar rates of

Variable HR (95% CI) P

CSM (P = 0.36) were noted in patients undergoing RNU.

CSM

1.0 RNU 0.89 (0.63–1.26) 0.50

NSS, Other Cause Death

Age 1.02 (1.0–1.03) 0.01

NTxU, Other Cause Death Year of diagnosis 1.01 (0.97–1.04) 0.64

0.8 NSS, Cancer-related Death Female gender 1.53 (1.11–2.11) 0.01

NTxU, Cancer-related Death Married 0.87 (0.63–1.21) 0.41

African-American race 1.20 (0.62–2.35) 0.59

Probability

0.6 Other race 1.02 (0.58–1.80) 0.94

Moderately differentiated tumours (G2) 1.53 (0.99–2.39) 0.06

ACM

0.4 RNU 0.78 (0.64–0.94) 0.009

Age 1.07 (1.06–1.08) <0.001

Year of diagnosis 0.99 (0.97–1.02) 0.60

0.2 Female gender 0.83 (0.69–0.99) 0.04

Married 0.83 (0.69–0.99) 0.04

African-American race 1.01 (0.65–1.57) 0.97

0.0 Other race 0.89 (0.65–1.21) 0.45

0 5 10 15 Moderately differentiated tumours (G2) 1.12 (0.91–1.38) 0.29

Years One prior cancer diagnosis 1.04 (0.84–1.28) 0.70

Number obs. Two prior cancer diagnoses 1.25 (1.01–1.54) 0.04

NSS 320 132 41 9

NTxU 907 493 224 37

for low- or moderate-grade, non-invasive UTUC when

multiple prior cancer diagnoses (HR 1.25, 95% 95% CI compared with patients undergoing RNU. Using such a

1.01–1.54, P = 0.04) were significantly associated with an national cancer registry to assess mortality trends is

increased risk of ACM. Despite no demonstrable differences in advantageous, as UTUC is a rare disease with an annual

CSM, patients with UTUC with non-high grade, low-stage incidence of one to two cases per 100 000 individuals in

disease undergoing RNU had an overall improvement in Western countries [3]. With a poor overall prognosis, patients

cancer-specific death (log-rank P < 0.001) compared with with UTUC with ≥pT2 disease have a 5-year overall survival

patients undergoing NSM (Fig. 1). rate of <50%, while patients with non-invasive disease have

much higher rates of cure [19].

Discussion Management of patients with UTUC has developed greatly

The present study is the first population-based analysis over the past two decades and now includes NSM, e.g.

showing comparable CSM in patients managed conservatively endoscopic ablation/segmental ureterectomy, in addition to

© 2013 The Authors

218 BJU International © 2013 BJU International

Nephron sparing vs radical nephroureterectomy for UTUC

open and minimally invasive RNU. Previous efforts to define undergoing NSM over RNU. In contrast, administrative

the role of non-extirpative treatment options in patients with datasets suggest a selection bias for non-nephron sparing

UTUC showed promising results in small series. In a seminal approaches in patients with RCC [29]. This difference is

report on the ureteroscopic management of UTUC in patients probably due to increased expected perioperative morbidity

with low- or moderate-grade, low-stage disease, Chen and for patients undergoing nephron-sparing surgery for RCC,

Bagley [13] reported acceptable oncological outcomes in 23 while in UTUC it is in fact the radical resection, which

patients undergoing laser ablation with strict ureteroscopic exposes patients to highest perioperative risks [30]. Previous

surveillance. Similarly, in a larger series of the endoscopic studies examining the oncological efficacy in patients managed

management of upper tract tumours, Gadzinski et al. [8] conservatively have been limited by small sample sizes, lack

reported equivalent 5-year CSM rates in 34 patients who of generalizability, and inclusion of patients with aggressive

underwent endoscopic management to 62 patients that disease characteristics. Using national registry data, the present

underwent RNU. Additionally, in a SEER analysis reviewing study suggests equivalent CSM in patients with low- or

outcomes of 569 segmental ureterectomy patients, Jeldres moderate-grade, low-stage UTUC (1227 patients) undergoing

et al. [20] reported comparable CSM to RNU patients when NSM compared with those undergoing RNU.

stratified by pathological stage.

The present retrospective cohort study has important

As a result, the use of NSM, e.g. endoscopic ablation and limitations that must be acknowledged when integrating these

segmental ureterectomy, has become an acceptable alternative data into clinical management decisions. Characteristics

in select patients with non-high grade, low-stage UTUC who inherent to SEER-based studies include a lack of patient-

are at low risk of disease progression [21,22]. However, while specific comorbidity data, concomitant malignancy data,

the risk of cancer progression or recurrence is estimated peri-procedural complication data, tumour anatomical data,

to be as high as 30% within 5 years [8,23], patients managed baseline renal function, and surgeon preferences for treatment.

conservatively mandate close endoscopic surveillance as often Due to the limits of using SEER coding data for non-extirpative

as every 3 months. As such, endoscopic management has UTUC surgical treatments, we relied on stratifying our cohorts

not been shown to adversely affect postoperative disease solely through the performance of extirpative kidney surgery for

status in the event subsequent RNU becomes necessary [9]. the management of UTUC. As such, a small portion of patients

The invasive surgical treatment of low- or moderate-grade, who were included in the endoscopy group may not have

low-stage UTUC is in stark contrast to the advocated received treatment. Further, SEER only captures and records

treatment regimens of low-stage renal cancer. Currently, the most advanced pathological stage along a patient’s disease

nephron-sparing surgery is recommended for the course, which limits the present cohort to patients with

management of cT1 renal masses [24], as contemporary documented low- or moderate-grade, low-stage disease

studies have suggested the deleterious effects of solitary kidney managed with conservative techniques who did not progress to

status, such as increased rates of renal insufficiency [5–7,25]. more intensive therapy. Also, patients who were upstaged at

In a large multi-institutional analysis, Kaag et al. [26] segmental ureterectomy of RNU were excluded, while patients

identified a reduction in mean estimated GFR by ≈24% after who underwent endoscopic management may have harboured

RNU in patients with UTUC. Thus, similar to radical more advanced grade/stage pathology. Despite these important

nephrectomy in patients with parenchymal renal masses, limitations, the present finding of acceptable oncological control

patients undergoing RNU have notable decreases in renal in patients who underwent NSM for low- or moderate-grade,

function and resulting chronic kidney disease [26,27]. low-stage UTUC is relevant, as selection of patients for these

Importantly, such a decline in renal function after radical non-extirpative treatments appears to have been appropriate

surgery in patients with UTUC may affect eligibility for even in a large administrative dataset.

adjuvant chemotherapy in the event of disease progression. In conclusion, we report that NSM (endoscopic ablation and

Furthermore, given the multifocal nature of urothelial segmental ureterectomy) in non-high grade, low-stage UTUC

carcinoma, patients after RNU are at significant life-long in a population-based analysis are more often performed for

risk for tumour recurrence in the remaining solitary renal older patients who are more likely to die of other causes, but

unit [28]. have acceptable cancer-specific survival outcomes. These data

The present study shows equivalent cancer-specific outcomes may be useful in counselling patients with UTUC about

in a large cohort of patients with low- or moderate-grade, treatment options. In the absence of level I evidence,

low-stage UTUC managed through NSM compared with non-extirpative management of UTUC should be informed

patients undergoing RNU. We used a competing risks analysis by prudent clinical judgment.

for appropriate risk adjustment, given that patients who

underwent NSM were significantly older and were more Acknowledgements

likely to die of other causes. In fact, the present data suggest a This publication was supported in part by grant number P30

strong selection bias for patients with shorter life-expectancy CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute (R.G.U.). The

© 2013 The Authors

BJU International © 2013 BJU International 219

Simhan et al.

content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not 17 Silberstein JL, Power NE, Savage C et al. Renal function and oncologic

necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer outcomes of parenchymal sparing ureteral resection versus radical

nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol 2012;

Institute or the National Institutes of Health. 187: 429–34

The authors were supported in part through the National 18 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Research

Cancer Data (1973–2007), National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance

Institutes of Health R03CA152388 (B.L.E.), and Department of

Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2010, based on

Defense, Physician Research Training Award (A.K.). the November 2009 submission. Available at: http://www.seer.cancer.gov

Accessed 1 March 2013

Conflict of Interests 19 Abouassaly R, Alibhai SM, Shah N, Timilshina N, Fleshner N, Finelli A.

Troubling outcomes from population-level analysis of surgery for upper

None declared. tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology 2010; 76: 895–901

20 Jeldres C, Lughezzani G, Sun M et al. Segmental ureterectomy can safely

References be performed in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter.

J Urol 2010; 183: 1324–9

1 Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J

21 Pohar KS, Sheinfeld J. When is partial ureterectomy acceptable for

Clin 2012; 62: 10–29

transitional-cell carcinoma of the ureter? J Endourol 2001; 15: 405–8

2 Raman JD, Scherr DS. Management of patients with upper urinary tract

22 Elliott DS, Segura JW, Lightner D, Patterson DE, Blute ML. Is

transitional cell carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Urol 2007; 4: 432–43

nephroureterectomy necessary in all cases of upper tract transitional cell

3 Roupret M, Zigeuner R, Palou J et al. European guidelines for the carcinoma? Long-term results of conservative endourologic management

diagnosis and management of upper urinary tract urothelial cell of upper tract transitional cell carcinoma in individuals with a normal

carcinomas: 2011 update. Eur Urol 2011; 59: 584–94 contralateral kidney. Urology 2001; 58: 174–8

4 Margulis V, Shariat SF, Matin SF et al. Outcomes of radical 23 Hall MC, Womack S, Sagalowsky AI, Carmody T, Erickstad MD,

nephroureterectomy: a series from the Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Roehrborn CG. Prognostic factors, recurrence, and survival in

Collaboration. Cancer 2009; 115: 1224–33 transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: a 30-year

5 Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM et al. Chronic kidney disease after experience in 252 patients. Urology 1998; 52: 594–601

nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective 24 Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A et al. Guideline for management

cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 735–40 of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol 2009; 182: 1271–9

6 McKiernan J, Simmons R, Katz J, Russo P. Natural history of chronic 25 Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCullouch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney

renal insufficiency after partial and radical nephrectomy. Urology 2002; disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization.

59: 816–20 N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1296–305

7 Zini L, Perrotte P, Capitanio U et al. Radical versus partial nephrectomy: 26 Kaag MG, O’Malley RL, O’Malley P et al. Changes in renal function

effect on overall and noncancer mortality. Cancer 2009; 115: 1465–71 following nephroureterectomy may affect the use of perioperative

8 Gadzinski AJ, Roberts WW, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS Jr. Long-term chemotherapy. Eur Urol 2010; 58: 581–7

outcomes of nephroureterectomy versus endoscopic management for 27 Lane BR, Smith AK, Larson BT et al. Chronic kidney disease after

upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol 2010; 183: 2148–53 nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma and

9 Lucas SM, Svatek RS, Olgin G et al. Conservative management in implications for the administration of perioperative chemotherapy.

selected patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma compares Cancer 2010; 116: 2967–73

favourably with early radical surgery. BJU Int 2008; 102: 172–6 28 Kang CH, Yu TJ, Hsieh HH et al. The development of bladder tumors

10 Roupret M, Hupertan V, Traxer O et al. Comparison of open and contralateral upper urinary tract tumors after primary transitional

nephroureterectomy and ureteroscopic and percutaneous management of cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract. Cancer 2003; 98: 1620–6

upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology 2006; 67: 1181–7 29 Smaldone MC, Egleston B, Uzzo RG, Kutikov A. Does partial

11 Smith AK, Stephenson AJ, Lane BR et al. Inadequacy of biopsy for nephrectomy result in a durable overall survival benefit in the medicare

diagnosis of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: implications for population? J Urol 2012; 188: 2089–94

conservative management. Urology 2011; 78: 82–6 30 Kutikov A, Smaldone MC, Egleston BL, Uzzo RG. Should partial

12 Iborra I, Solsona E, Casanova J et al. Conservative elective treatment of nephrectomy be offered to all patients whenever technically feasible? Eur

upper urinary tract tumors: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors Urol 2012; 61: 732–4

for recurrence and progression. J Urol 2003; 169: 82–5

13 Chen GL, Bagley DH. Ureteroscopic management of upper tract

Correspondence: Alexander Kutikov, Fox Chase Cancer

transitional cell carcinoma in patients with normal contralateral kidneys.

J Urol 2000; 164: 1173–6 Center, Temple University School of Medicine, 333 Cottman

14 Clements T, Messer JC, Terrell JD et al. High-grade ureteroscopic biopsy Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19111, USA.

is associated with advanced pathology of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma

tumors at definitive surgical resection. J Endourol 2012; 26: 398–402

e-mail: alexander.kutikov@fccc.edu

15 Lehmann J, Suttmann H, Kovac I et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the Abbreviations: ACM, all-cause mortality; CSM, cancer-specific

ureter: prognostic factors influencing progression and survival. Eur Urol

mortality; HR, hazard ratio; NSM, nephron-sparing

2007; 51: 1281–8

16 Tavora F, Fajardo DA, Lee TK et al. Small endoscopic biopsies of the

measures; OCM, other-cause mortality; RNU, radical

ureter and renal pelvis: pathologic pitfalls. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33: nephroureterectomy; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and

1540–6 End Results; UTUC, upper tract urothelial carcinoma.

© 2013 The Authors

220 BJU International © 2013 BJU International

You might also like

- Breast Cancer Report Sample High enDocument1 pageBreast Cancer Report Sample High enNishant Kini100% (1)

- Comparison of Radical Cystectomy With Conservative Treatment in Geriatric ( 80) Patients With Muscle-Invasive Bladder CancerDocument9 pagesComparison of Radical Cystectomy With Conservative Treatment in Geriatric ( 80) Patients With Muscle-Invasive Bladder CancerjustforuroNo ratings yet

- IkjjjkjDocument7 pagesIkjjjkjMohammad AjiNo ratings yet

- 2022 48 3 3675 EnglishDocument10 pages2022 48 3 3675 EnglishRaul Matute MartinNo ratings yet

- Ye 2013Document12 pagesYe 2013Mimsy Quiñones TafurNo ratings yet

- TouijerDocument7 pagesTouijerVinko GrubišićNo ratings yet

- PIIS0003497509010868Document6 pagesPIIS0003497509010868Karthik SgNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Value of Metabolic Tumor Burden On F-FDG PET in Nonsurgical Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung CancerDocument12 pagesPrognostic Value of Metabolic Tumor Burden On F-FDG PET in Nonsurgical Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung CancerAmina GoharyNo ratings yet

- EeDocument8 pagesEeEstiPramestiningtyasNo ratings yet

- Cancer GinjalDocument6 pagesCancer GinjalTutut setiowatiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2531043719302156 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2531043719302156 Mainpulmonologi UnsyiahNo ratings yet

- Baek 2017Document10 pagesBaek 2017witaNo ratings yet

- Bacciu 2013Document10 pagesBacciu 2013AshokNo ratings yet

- Esophageal Cancer Recurrence Patterns and Implicati 2013 Journal of ThoracicDocument5 pagesEsophageal Cancer Recurrence Patterns and Implicati 2013 Journal of ThoracicFlorin AchimNo ratings yet

- Principales Emergencias Oncológicas en El Cáncer de Pulmón: Un Análisis de Un Único CentroDocument3 pagesPrincipales Emergencias Oncológicas en El Cáncer de Pulmón: Un Análisis de Un Único CentroJoskarla MontillaNo ratings yet

- Survival Rates For Patients With Resected Gastric Adenocarcinoma Finally Have Increased in The United StatesDocument7 pagesSurvival Rates For Patients With Resected Gastric Adenocarcinoma Finally Have Increased in The United StatesXavier QuinteroNo ratings yet

- CA MammaeDocument6 pagesCA MammaeRiaNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Model For Survival of Local Recurrent Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma With Intensity-Modulated RadiotherapyDocument7 pagesPrognostic Model For Survival of Local Recurrent Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma With Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapypp kabsemarangNo ratings yet

- Wo2019 PosterDocument1 pageWo2019 PosterCx Tx HRTNo ratings yet

- 3961 FullDocument8 pages3961 FullMuhammad HabiburrahmanNo ratings yet

- Mallappa Et Al-2013-Colorectal DiseaseDocument6 pagesMallappa Et Al-2013-Colorectal DiseaseDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- BJC 201328Document7 pagesBJC 201328PraveenNo ratings yet

- Abdominoperineal Resection For Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma: Survival and Risk Factors For RecurrenceDocument8 pagesAbdominoperineal Resection For Squamous Cell Anal Carcinoma: Survival and Risk Factors For RecurrenceWitrisyah PutriNo ratings yet

- Albayrak 2016Document7 pagesAlbayrak 2016DavorIvanićNo ratings yet

- Clinical Impact of External Radiotherapy in Non-Metastatic Esophageal Cancer According To Histopathological SubtypeDocument12 pagesClinical Impact of External Radiotherapy in Non-Metastatic Esophageal Cancer According To Histopathological SubtypesilviailieNo ratings yet

- AS For Renal MassesDocument8 pagesAS For Renal MassesDiana VallejoNo ratings yet

- P. Wang Et Al.2019Document6 pagesP. Wang Et Al.2019Mai M. AlshalNo ratings yet

- A Volume Matched Comparison of Survival After Radiosurgery in Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients With One Versus More Than Twenty Brain MetastasesDocument7 pagesA Volume Matched Comparison of Survival After Radiosurgery in Non Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients With One Versus More Than Twenty Brain MetastasesPablo Castro PenaNo ratings yet

- Marcadores Sericos para Cole AgudaDocument6 pagesMarcadores Sericos para Cole Agudajessica MárquezNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Scientific Research: OncologyDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Scientific Research: OncologyRaul Matute MartinNo ratings yet

- Survival Analysis of Palliative Surgery of Advanced Stage Periampullary Cancer PDFDocument6 pagesSurvival Analysis of Palliative Surgery of Advanced Stage Periampullary Cancer PDFEko RistiyantoNo ratings yet

- Lotan Et Al. Molecular Marker For Rec and Cancer Specific Survival Post Radical CystectomyDocument7 pagesLotan Et Al. Molecular Marker For Rec and Cancer Specific Survival Post Radical CystectomyyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic Duct TextureDocument9 pagesPancreatic Duct TextureAdarsh GhoshNo ratings yet

- 10 1093@icvts@ivz140Document8 pages10 1093@icvts@ivz140PEDRO JESuS GUERRA CANCHARINo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Factors Related To The Survival of Metastatic Kidney Cancers: Retrospective Study at The Mohamed VI Center For The Cancer Treatment in Casablanca, MoroccoDocument5 pagesEpidemiology and Factors Related To The Survival of Metastatic Kidney Cancers: Retrospective Study at The Mohamed VI Center For The Cancer Treatment in Casablanca, MoroccoInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Time To Surgery After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Operable Breast Cancer PatientsDocument6 pagesImpact of Time To Surgery After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Operable Breast Cancer PatientsPani lookyeeNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Long-Term Survival Decades After Esophagectomy For Esophageal CancerDocument38 pagesDeterminants of Long-Term Survival Decades After Esophagectomy For Esophageal CancerJoão Gabriel Oliveira de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Systemic Therapy For Advanced Appendiceal Adenocarcinoma: An Analysis From The NCCN Oncology Outcomes Database For Colorectal CancerDocument8 pagesSystemic Therapy For Advanced Appendiceal Adenocarcinoma: An Analysis From The NCCN Oncology Outcomes Database For Colorectal Canceralberto cabelloNo ratings yet

- ANZ Journal of Surgery - 2021 - Yang - Outcomes of Patients With Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma To The Axilla PDFDocument8 pagesANZ Journal of Surgery - 2021 - Yang - Outcomes of Patients With Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma To The Axilla PDFRong LiuNo ratings yet

- Characterization of Adrenal Metastatic Cancer Using FDG PET CTDocument8 pagesCharacterization of Adrenal Metastatic Cancer Using FDG PET CTEngky ChristianNo ratings yet

- PDF PHDocument10 pagesPDF PHWennyNo ratings yet

- Hompes Completion TMEDocument6 pagesHompes Completion TMEMariana Sanches NavasNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Survival in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung CancerDocument7 pagesLong-Term Survival in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung CancerMrBuu2012No ratings yet

- 8424365Document8 pages8424365Melody CyyNo ratings yet

- Introduction & ObjectivesDocument2 pagesIntroduction & ObjectivessiuroNo ratings yet

- Selection of Modality For Diagnosis and Staging of Patients With Suspected Non-Small Cell Lung CancerDocument30 pagesSelection of Modality For Diagnosis and Staging of Patients With Suspected Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer4wntsgj69pNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Ultrasound and Early Diagnosis of Pancreatic CancerDocument4 pagesEndoscopic Ultrasound and Early Diagnosis of Pancreatic CancerAchmad Dzulfikar AziziNo ratings yet

- DTH 34 E14981Document9 pagesDTH 34 E14981Henry WijayaNo ratings yet

- Radiotherapy and Oncology: Perioperative Management of SarcomaDocument8 pagesRadiotherapy and Oncology: Perioperative Management of SarcomaNevine HannaNo ratings yet

- Does Tumor Grade Influence The Rate of Lymph Node Metastasis in Apparent Early Stage Ovarian Cancer?Document4 pagesDoes Tumor Grade Influence The Rate of Lymph Node Metastasis in Apparent Early Stage Ovarian Cancer?Herry SasukeNo ratings yet

- Ashworth 2013Document7 pagesAshworth 2013Laura QuirozNo ratings yet

- 10 Anos Cross Trial Jco2021Document11 pages10 Anos Cross Trial Jco2021alomeletyNo ratings yet

- Medicina: Diagnostic Performance of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in The Evaluation of Solid Renal MassesDocument8 pagesMedicina: Diagnostic Performance of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in The Evaluation of Solid Renal MassesAgamNo ratings yet

- EJGO2022054 Cervical CaDocument8 pagesEJGO2022054 Cervical CaRahmayantiYuliaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison Between The Reference Values of MRI and EUS and Their Usefulness To Surgeons in Rectal CancerDocument9 pagesA Comparison Between The Reference Values of MRI and EUS and Their Usefulness To Surgeons in Rectal CancerСергей СадовниковNo ratings yet

- 016 - The-Evolving-Landscape-of-Neuroendocr - 2023 - Surgical-Oncology-Clinics-of-NortDocument14 pages016 - The-Evolving-Landscape-of-Neuroendocr - 2023 - Surgical-Oncology-Clinics-of-NortDr-Mohammad Ali-Fayiz Al TamimiNo ratings yet

- Articulo Cilliani 3ra HistoriaDocument6 pagesArticulo Cilliani 3ra HistoriaFabricio Nuñez de la CruzNo ratings yet

- MDV 161Document12 pagesMDV 161rasika bhatNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Factors For Spinal Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas Treated With Postoperative Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy - A Large, Single-Institution ExperienceDocument10 pagesPrognostic Factors For Spinal Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas Treated With Postoperative Pencil-Beam Scanning Proton Therapy - A Large, Single-Institution ExperienceAnnisa RahmaNo ratings yet

- 01 Purpose and Principles of Cancer Staging PDFDocument12 pages01 Purpose and Principles of Cancer Staging PDFalyson100% (1)

- MDCT and MR Imaging of Acute Abdomen: New Technologies and Emerging IssuesFrom EverandMDCT and MR Imaging of Acute Abdomen: New Technologies and Emerging IssuesMichael PatlasNo ratings yet

- 2022 Article 16807Document11 pages2022 Article 16807yuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Prostate Cancer - Localised Vs Locally Advanced Vs AdvancedDocument15 pagesProstate Cancer - Localised Vs Locally Advanced Vs AdvancedyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0302283815001578 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0302283815001578 MainyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Penis Fracture - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument5 pagesPenis Fracture - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Lotan Et Al. Molecular Marker For Rec and Cancer Specific Survival Post Radical CystectomyDocument7 pagesLotan Et Al. Molecular Marker For Rec and Cancer Specific Survival Post Radical CystectomyyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Grreen Et Al. - Pre Cystectomy Prediction of NOC-UCDocument7 pagesGrreen Et Al. - Pre Cystectomy Prediction of NOC-UCyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Gibas Et Al. - Nonrandom Chromosomal Changes in TCC of The BladderDocument9 pagesGibas Et Al. - Nonrandom Chromosomal Changes in TCC of The BladderyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- McConkey Et Al. - Molecular Genetics of BCa - Emerging Mechanisms of Tumor Initiation and ProgressionDocument12 pagesMcConkey Et Al. - Molecular Genetics of BCa - Emerging Mechanisms of Tumor Initiation and ProgressionyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Gibas Et Al. - A Possible Specific Chromosome Change in Transitional Cell Carcinoma of The BladderDocument10 pagesGibas Et Al. - A Possible Specific Chromosome Change in Transitional Cell Carcinoma of The BladderyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Sens and SpecDocument14 pagesSens and SpecyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- BMC Infectious Diseases: Study ProtocolDocument9 pagesBMC Infectious Diseases: Study ProtocolyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Tuziak Et Al. - High-Resolution Whole-Organ Mapping With SNPs and Its Significance To Early Events of CarcinogenesisDocument13 pagesTuziak Et Al. - High-Resolution Whole-Organ Mapping With SNPs and Its Significance To Early Events of CarcinogenesisyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- An Outcome Model For High-Risk NMIBC Treatment OptionsDocument1 pageAn Outcome Model For High-Risk NMIBC Treatment OptionsyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Letouze Et Al. - TuMult For Copy Number AnalysisDocument19 pagesLetouze Et Al. - TuMult For Copy Number AnalysisyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Heidenreich Et Al. - Anatomic Extent of Pelvic Lymphadenectomy in Bladder CancerDocument5 pagesHeidenreich Et Al. - Anatomic Extent of Pelvic Lymphadenectomy in Bladder CanceryuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Prostate Cancer - StagesDocument6 pagesProstate Cancer - StagesyuenkeithNo ratings yet

- Guggenheim 2012Document7 pagesGuggenheim 2012Andreea PodaruNo ratings yet

- H-046-003257-00 FERRITIN KIT (CLIA) Muti LaguageDocument15 pagesH-046-003257-00 FERRITIN KIT (CLIA) Muti LaguageSinari AlfatNo ratings yet

- Relative ClauseDocument4 pagesRelative ClauseZu Zu KhinNo ratings yet

- Dermoscopy of Inflamed Seborrheic KeratosisDocument9 pagesDermoscopy of Inflamed Seborrheic KeratosisFreddy RojasNo ratings yet

- The Awakening From ChildhoodDocument3 pagesThe Awakening From ChildhoodDafer M. EnrijoNo ratings yet

- Cross-Sectional Imaging of The Duodenum - Spectrum of DiseaseDocument64 pagesCross-Sectional Imaging of The Duodenum - Spectrum of DiseasedianalopezalvarezNo ratings yet

- Application Form - Essay Prize 2020Document4 pagesApplication Form - Essay Prize 2020John SmithNo ratings yet

- Educational Topic 40 - Disorders of The BreastDocument2 pagesEducational Topic 40 - Disorders of The BreastEmily VlasikNo ratings yet

- SOAL UAS CT LANJUT Mei 2021Document7 pagesSOAL UAS CT LANJUT Mei 2021fahan muhandisNo ratings yet

- Proton TherapyDocument21 pagesProton Therapytrieu leNo ratings yet

- GCT Giant Cell Tumor PresentationDocument22 pagesGCT Giant Cell Tumor PresentationHasyasya Furnita KosaziNo ratings yet

- National Cancer Treatment GuidelinesDocument416 pagesNational Cancer Treatment Guidelinesmelinaabraham2019No ratings yet

- TPS ContouringDocument19 pagesTPS ContouringEskadmas BelayNo ratings yet

- Celebration of The Cells - Letters From A Cancer SurvivorDocument189 pagesCelebration of The Cells - Letters From A Cancer SurvivorRonak Sutaria100% (2)

- Immuno OncologyDocument4 pagesImmuno OncologydanieleNo ratings yet

- Breast Surgery Indications and TechniquesDocument302 pagesBreast Surgery Indications and TechniquesLasha OsepaishviliNo ratings yet

- Skin CancerDocument9 pagesSkin CancerIvan AuliaNo ratings yet

- Solid TumoursDocument48 pagesSolid TumoursViswanadh BNo ratings yet

- Koding Diagnosa CancerDocument6 pagesKoding Diagnosa CancerFarmasi SitostatikNo ratings yet

- Eg 3870 UtkDocument2 pagesEg 3870 UtkAliabdulghaniNo ratings yet

- Unit 5: Diagnosis Part 2: Medical History Identify UtilizeDocument4 pagesUnit 5: Diagnosis Part 2: Medical History Identify UtilizeAnonymous Wfl201YbYoNo ratings yet

- 7th Kent ENdoscopy Training Hybrid Course Registration ProgrammeDocument3 pages7th Kent ENdoscopy Training Hybrid Course Registration ProgrammeJustine OyanibNo ratings yet

- HafizahDocument407 pagesHafizahmfaizalxcNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Colorectal CancerDocument2 pagesPathophysiology of Colorectal CancerMp WhNo ratings yet

- Alpha Liquid 100 Samp RepDocument32 pagesAlpha Liquid 100 Samp RepAdriel MirtoNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Asscociated Factors of Ovarian Cyst Malignancy: A Cros-Sectional Based Study in SurabayaDocument6 pagesPrevalence and Asscociated Factors of Ovarian Cyst Malignancy: A Cros-Sectional Based Study in SurabayakarenNo ratings yet

- CALGB Schema FinalDocument1 pageCALGB Schema FinalMohamed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Cancer - March 1969 - Johnson - Eccrine Acrospiroma A Clinicopathologic StudyDocument17 pagesCancer - March 1969 - Johnson - Eccrine Acrospiroma A Clinicopathologic StudyIsa EnacheNo ratings yet

- Onco Quiz 1Document2 pagesOnco Quiz 1Andrea Mae BernardoNo ratings yet