Professional Documents

Culture Documents

12 Chapter 10

12 Chapter 10

Uploaded by

Bipasha ShahCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

12 Chapter 10

12 Chapter 10

Uploaded by

Bipasha ShahCopyright:

Available Formats

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

CHAPTER 10

SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND

RELAVANT POLICY IMPLICATIONS

In developing country like India, being the major agro-based industry, the sugar industry

facilitates the process of resource mobilization, employment generation (both direct and

indirect), income creation, and development of social and physical infrastructure. Recognizing its

importance in the rural economy, the policy makers recognized that the expansion of sugar

industry can tackle a large number of economic tribulations that are present in rural India. India

is world’s largest consumer of sugar and also second largest producer next to Brazil. At present,

453 (out of the total of 568) sugar firms are operating in India and the installed capacity of these

mills is ranging between below 1,250 tonnes crushed per day (TCD) of sugarcane and 10,000

TCD. These mills provide direct employment to 0.5 million skilled and unskilled workers and

engage 55 million peoples directly or indirectly in sugarcane cultivation, harvesting and ancillary

activities. The industry also contributes Rs. 25 billion annually to the center and state exchequer

in the form of taxes (ISMA, 2004). Further, with its potential to generate 5000 mega watt (MW)

surplus power through the process of cogeneration, the industry can ease the energy crisis of

Indian economy. In addition, the production of ethanol using molasses (the byproduct of sugar)

and blending it with petrol can also help to cut a fraction of rising balance of payments (BOPs)

deficit due to mounting imports bill for petroleum products.

Nevertheless, the statistics provided by Standing Committee on Food, Civil Supply and

Public Distribution (2003) explicitly describe the appalling status of the health of Indian sugar

industry. The Committee pointed out that 76 sugar mills of private and public sectors are sick

and 42 of these mills have remained closed for the last five sugar seasons or more. In addition,

123 cooperative sugar mills have also been observed carrying negative net worth. On the whole,

out of the 568 sugar mills, 199 sugar mills (i.e., 35 percent mills) are found to be running either

with the negative net worth or designated as sick units. It has been well acknowledged by the

industry experts that the dismal performance of sugar industry is the product of both internal and

external environmental factors. The external factors are primarily uncontrollable from

management point of view (like decreasing area under sugarcane cultivation, tight government

regulations in pricing and distribution of sugar, rainfall deficit, etc.) and their effect is almost

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 252

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

uniform on the overall performance of the sugar industry. However, the internal factors which

are largely controllable in nature (like low level of capacity utilization, inefficient use of inputs,

labour unrest, and managerial underperformance etc.) also contribute to a dismal performance of

the sugar industry, but their effect varies from one sugar mill to another.

It has been felt by the government appointed committees and industry experts that an

improvement in the health of the Indian sugar industry is possible only through the efficient

operations of sugar firms with minimum wastage of key resources and almost zero excess

capacity. Against this background, any attempt to monitor the health of Indian sugar industry in

terms of productivity, efficiency and capacity utilization improvement over time would surely

help to understand the dynamics of growth and performance of the industry and shock absorptive

capacity of the industry against the odds like price spiraling in the global and domestic markets

and stiff government regulations. It is well acknowledged fact in the literature that the

implementation of the efficient production operations given the existing state of technology

ensures higher levels of total factor productivity (TFP). If the technology is not progressing in an

industry, improving the technical efficiency of the firms is usually a more cost effective and

desirable pursuit to experience TFP growth. On the other hand, if firms are reasonably

technically efficient then an increase in TFP requires shifting the production function upward so

as to attain a decent output growth. Given the dismal performance of Indian sugar industry in the

recent years, it is pertinent to know i) whether Indian sugar firms are efficiently using the

resources or not; ii) whether TFP is growing or not; and iii) whether excess capacity is reducing

or not. In the present study an attempt has been made in this direction. The major objectives of

the present study are outlined as follows:

1) To examine the inter-temporal and inter-state variations in capacity utilization of sugar

industry;

2) Measuring the extent of technical inefficiency in Indian sugar industry;

3) Identification of the sources of technical inefficiency in Indian sugar industry at

aggregated and disaggregated (state) levels;

4) Decomposing the sources of output growth in Indian sugar industry;

5) Testing of convergence in growth and efficiency levels in Indian sugar industry; and

6) Examining the macroeconomic nexus between the growth of sugar industry and

economic growth in 12 major sugar producing states;

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 253

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

In order to present the findings of the study in a lucid style the entire study has been

organized into ten chapters. The Chapter 1 is introductory in nature and discusses the importance

and structure of the sugar industry of India. A thorough discussion regarding the development of

sugar industry during the plan periods depicts that India is the world’s largest sugar consumer,

second largest producer-next to Brazil, and remained the net exporter of the sugar during the

planning era. The analysis of the importance of the major byproducts of sugar reflects that with

its potential to generate 5000MW surplus power through the process of cogeneration, the

industry can ease the energy crisis of Indian economy. The diversification of the production

operations towards the production of ethanol using molasses (the byproduct of sugar) and

blending it with petrol can also help to cut a fraction of rising balance of payments (BOP) deficit

due to mounting imports bill for petroleum products. Moreover, the rationale of conducting the

present study has also been discussed along with the objectives and the null hypotheses to be

tested.

The Chapter 2 provides a theoretical framework of measuring technical efficiency. Both

parametric and non-parametric techniques of measuring technical efficiency have been discussed

in detail along with the pros and cons of each technique. Further, the techniques of stochastic

data envelopment analysis (SDEA) and DEA bootstrapping have been discussed to marry the

virtues of both DEA and stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) techniques. It has been observed that

DEA bootstrapping techniques are most superior to all other indigenous techniques and best

suited for the data sets to be utilized for the present study purpose.

In Chapter 3, the importance and methods to measure TFP growth have been discussed.

A survey of all the available techniques reveals that Malmquist productivity index enables the

researchers to decompose the TFP growth into efficiency change and technical progress. Further,

the component of efficiency change can be decomposed into pure efficiency change and scale

efficiency change together with the decomposition of technical progress into Hicks neutral and

non-neutral types of technical progress. The bootstrapping techniques given by Simar and

Wilson (1999) have also been discussed to check the significance of productivity scores.

The methods of measuring capacity utilization have been discussed in Chapter 4. The

theoretical survey of various methods provide that the existing literature on measuring CU spells

out two competing approaches to measure CU levels: i) engineering methods to measure CU;

and ii) economist’s approach to measure of CU. The engineering method is superior to the

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 254

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

economists’ measure because of its feature to determine CU levels without the information on

input prices. Moreover, the literature supports the fact that when the cost curves are L-shaped in

nature (as empirically supported in Microeconomics text books), the engineering measure

approximate the economists’ measure of CU (Johanston, 1960). Thus, the engineering measure

of CU using the technique of DEA has been preferred for analyzing the inter-temporal and inter-

state variations in CU of Indian sugar industry at aggregated and disaggregated levels.

A detailed review of the literature on measuring capacity utilization, technical efficiency,

and TFP growth of Indian manufacturing as well as of Indian sugar industry has been provided in

Chapter 5. It has been observed that several Indian researchers have endeavored to estimate the

capacity utilization (CU) in Indian manufacturing at different levels of aggregations. Some of

these attempts examined the CU trends in Indian manufacturing at highly aggregated level

covering the given industry or All-India’s manufacturing sector [see e.g., Gulati (1959), Budhin

and Paul (1961), NCAER (1966), Koti (1968), RBI (1968), Divetia and Verma (1970), RBI

(1972), Paul (1974a), Karim and Bhinde (1975), Seth (1986), Azeez (2002)], some of the studies

analyzed trends in CU for an individual industry [see e.g., Nag (1961), Commerce Research

Bureau (1968), Sandesara (1969), Gupta and Thavaraj (1975), Sastry (1980), Bhanu (2006)],

Amongst all these, the study by Bose (1964) is an attempt to examine CU variations at regional

level. However, the literature on measuring technical efficiency has also been classified among

three categories. Some analyzing technical efficiency of single industry [see e.g., Subramaniyan

(1982), Jha and Sahni (1993), Majumdar (1994), Ferrantino and Ferrier (1995), Ferrantino et al.

(1995), Ferrantino and Ferrier (1996), Kumar and Pillai (1996), Murty et al. (2006), Singh

(2006a), Singh (2006b), Singh (2007), Singh et al. (2007)], some for group of industries at

highly aggregated level [see e.g., Goldar (1985), Nath (1996), Aggarwal (2001a), Aggarwal

(2001b), Parmeswarn (2002), Ray (2002), Goldar, et al. (2004), Ray (2004), Nikaido (2005),

Kambhampati (2006), Mahambare and Balasubramanyam (2005), Kumar and Arora (2007),

Kumar and Arora (2007)], and some other analyzing efficiency at regional levels [see e.g., Neogi

and Ghosh (1994), Gajanan (1995), Mitra (1999), Kumar (2000), Rajesh and Duraisamy (2002)].

Among all of these studies, some of the aforementioned research attempts have been made

corresponding to the evaluation of technical efficiency of Indian sugar industry in general [see

e.g., Subramaniya (1982), Jha and Sahni (1993), Ferrantino et al. (1995), Ferrantino and Ferrier

(1995), Ferrantino and Ferrier (1996), and Murty et al. (2006)] or of sugar industry of an

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 255

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

individual state in particular [see e.g., Singh (2006a), Singh (2006b), Singh (2007), Singh et al.

(2007)]. However, a thorough analysis of the literature on measuring the TFP growth represents

some of the studies on measuring TFP at highly aggregated levels [see e.g., Neogi and Ghosh

(1998), Pradhan and Barik (1999), Singh (2000-01), Goldar and Kumari (2003)], at single

industry level [see e.g., Beri (1962), Sastry (1966), Mehta (1974), Gupta and Patel (1976), Singh

and Singh (1984), Dawar (1990), Sharma and Upadhayay (2003-04), Singh and Agarwal (2006),

Singh (2006c)], and at regional levels [see e.g., Singh (1964), Ray (1997), Mitra (1999), Ray

(2002), Kumar (2003), Chattopadhyay (2004), Kumar and Arora (2009)]. Thus, the analysis of

the existing literature reveals that still there exist a void on measuring the inter-temporal and

inter-state variations in CU, technical efficiency and TFP growth in Indian sugar industry in

general and sugar industry of 12 major sugar producing states in particular. The present study is

an attempt in this direction and tries to fill up the already existing void in the literature.

The empirical evidences regarding the inter-temporal and inter-state variations in CU

have been given in Chapter 6. A non-parametric model developed by Färe et al. (1989) has been

applied to attain the capacity utilization levels for the Indian sugar industry and sugar industry of

12 major sugar producing states. The major findings of the empirical analysis are:

1) The average amount of excess capacity (EC) in Indian sugar industry is about 13 percent

in the each year of the study period;

2) Excess capacity increased significantly by about 15 percent in the post-reforms period

(1991/92 to 2004/05) relative to the pre-reforms period (1974/75 to 1990/91);

3) Except two states, namely, Maharashtra and Karnataka, EC levels are found to be above

All-India level in remaining 10 states;

4) Barring the sugar industry of Rajasthan, an increase in the EC levels of remaining 11

sugar producing states have been observed during the post-reforms period in comparison

of the pre-reforms period;

5) Except the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan, decline in CU is statistically significant for

the remaining 10 sugar producing states and sugar industry of all-India;

6) The CU levels followed a path of deceleration (as ascertained by negative growth rates)

during the entire study period and the deceleration become more noticeable during the

post-reforms period;

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 256

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

7) To operate on full capacity level, 46.04 percent of more intermediate inputs and 195.8

percent of more labour are needed, which indicates that, reaching at full capacity would

surely increase the employment in the industry;

8) Except the states of Karnataka and Rajasthan, each state has exhibited an increase in

potential intermediate inputs requirement during the post-reforms period as compare to

the pre-reforms period;

9) The potential labour requirement has increased for all states during the post-reforms

period;

10) The impact of environmental variable (K/L) on CU is negative and significant. Therefore,

an increase in capital-intensity found to be adding up the existing excess capacity levels

in the industry; and

11) The availability of raw material is a major determinant of capacity utilization.

In the light of aforementioned results, we reject the hypothesis of optimum capacity utilization in

Indian sugar industry at both national and state levels. Among the factors causing CU, shortage

of raw material has been identified as the major factor causing underutilization of capacity.

In Chapter 7, attempt has been made to analyze the inter-temporal and inter-state

variations in overall technical, pure technical and scale efficiency. Two DEA models CCR and

BCC with boot-strapping have been applied to attain the technical efficiency levels in Indian

sugar industry. Following are the major findings of the efficiency analysis:

1) A high average overall technical inefficiency (OTIE) to the tune of 35.55 percent has

been observed for Indian sugar industry;

2) Above 80 percent of the OTIE has been contributed by managerial sub-performance i.e.,

30.75 percentage points of 35.55 percent OTIE has been explained by pure technical

inefficiency (PTIE). Thus, managerial inefficiency is dominant and statistically

significant source and scale inefficiency is relatively scant and statistically insignificant

source of technical inefficiency in Indian sugar industry;

3) Dominance of managerial inefficiency (i.e., PTIE) is a countrywide phenomenon and not

limited to a particular state;

4) The economic reforms have found to be worsening technical efficiency levels in Indian

sugar industry and sugar industry of 12 major sugar producing states;

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 257

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

5) The phenomenon of technical efficiency convergence found to be present during the pre-

reforms period, which goes disappear during the post-reforms period. Moreover, the TE

convergence hypothesis cannot be rejected for the entire study period too;

6) The panel data Tobit regression analysis about factors causing technical efficiency

reveals that the environmental variable SKILL is causing all the three measures of

technical efficiency positively and significantly. However, the variable RETURN is

although affecting the three measures of efficiency positively, yet its impact on scale

efficiency measure is statistically insignificant; and

7) The proxy variable of capital intensity i.e., (K/L) bears a negative and statistically

significant impact on three measures of efficiency. Such a negative impact of (K/L) is

despite of already existing excess capacity in the sugar industry of India.

The results, thus, illustrate an average inefficiency to the tune of 35.55 percent, which is high by

all standards and observed to be primarily caused by the managerial inefficiency. Also, the

hypothesis of efficiency catch-up has been completely rejected for the post-reforms period

whereas, for the pre-reforms period and entire study period, catching-up do exist in Indian sugar

industry. The lack of the skilled manpower and low profitability have been observed the major

factors responsible for rising technical inefficiency in Indian sugar industry.

Using the growth accounting framework, the Chapter 8 presents the decomposition of

output growth in two mutually exclusive components viz., inputs growth and TFP growth. The

non-parametric DEA based Malmquist productivity index has been operationalized to

decompose TFP growth into two mutually exclusive components viz., efficiency change and

technological progress. The efficiency change has further been bifurcated into pure efficiency

change and scale efficiency change whereas, the technical progress has been decomposed into

Hicks neutral and non-neutral types of technical progress. The following are the major outcomes

of the TFP analysis:

1) Output in Indian sugar industry has grown at the rate of 1.838 percent per annum;

2) The inspiration component i.e., TFP in Indian sugar industry has recorded a growth rate

to the tune of 2.43 percent per annum;

3) A negative growth of perspiration component i.e., factor accumulation has been noticed

to the tune of -0.592 percent;

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 258

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

4) Thus, the analysis reveals that factor accumulation has restricted the Indian sugar

industry to achieve potential growth rates of output. If we assume that input growth is

zero, the industry must have grown at the potential growth rate equal to the TFP growth

of 2.43 percent. Nevertheless, if the inputs growth becomes positive, the industry can

record much higher growth rates of sugar output;

5) TFP is primarily attributable to efficiency change in general and managerial efficiency

change (PECH) in particular during entire period;

6) The decline in the growth rate of managerial efficiency during the post-reforms period

has been observed to be the major cause of sluggishness in TFP growth during the post-

reforms period;

7) During the post-reforms period technical progress is positive relative to a technical

regress for pre-reforms period. It is worth mentioning here that the negative technical

progress during the pre-reforms period seems to be the results of stiff and regulatory

environment imposed upon the industry during the pre-reforms period. Under adverse

environmental conditions, even the most efficient firms may face trouble in transforming

inputs into outputs at the rate to which they had previously been accustomed. Despite of

it, the observed level of best-practice technology may deteriorate, as reflected by a

downward shift of the industry’s production frontier (Ferrantino and Ferrier, 1996). This

technical regress is a different phenomenon from a decrease in efficiency as it also affects

the most efficient firms. Indeed, the measured efficiency level of the inefficient firms

may improve during the period of adversity due to the ‘regress’ of the most efficient

firms i.e., the frontier may move closer to the inefficient firms rather than the inefficient

firms moving closer to the frontier;

8) The nature of technical progress is Hicks neutral in nature;

9) The test of output growth convergence hypothesis completely rules out the existence of

catching-up or learning by doings process; and

10) The five out of 12 sugar producing states are found to be forming the convergence club.

The affiliates of convergence club are Gujarat, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, and

Rajasthan.

It is evident from above results that a regress in inputs (i.e., negative inputs growth) restricts the

potential output growth in Indian sugar industry. Thus, the null hypothesis that the inputs growth

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 259

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

is positively contributing output growth is liable to be rejected. However, the null hypothesis of

the significant TFP growth cannot be rejected. The TFP growth in Indian sugar industry has been

found to be dominated by efficiency change in pre-reforms period and by technical progress

during the post-reforms period. Further, most of the output growth during the post-reforms

period is contributed by the Hicks neutral type of technical progress.

In Chapter 9, the long-run relationship between growth of sugar industry and levels of

economic growth in 12 major sugar producing states has been explored using the panel-data

cointegration analysis. The main observations of this chapter are:

1) There exists a significant long run nexus between the growth of sugar industry and

economic growth of the 12 sugar producing states of India;

2) Any increase in sugar output speed up the economic growth of the 12 major sugar

producing states;

3) The cointegration analysis about the importance of the each determinant of output growth

reflects that input growth is the most important and significant factor causing output

growth in long-run whereas, the impulse response analysis also reveals its importance in

short run; and

4) The panel data VECM based Granger causality analysis reveals that there exists

bidirectional relationship between output growth and inputs growth. The direct

connotation of this fact is that if the improvement of sugar industry requires the

substantial inputs growth then the inputs growth also calls for a substantial growth of the

sugar industry.

Therefore, a significant long-run sugar output elasticity of economic growth calls for an urgent

need of improving the health of Indian sugar industry. However, the input growth has been found

to be the most effective policy variable, both for long-run and short-run, to improve the growth

performance of Indian sugar industry.

In the present concluding Chapter 10, the findings of the study have been summarized and

the major policy implications of the study have been highlighted. The following suggestions

have been put forward on the basis of derived policy implications:

1) Attempts must be taken to enhance the productivity and quality (in terms of sucrose

contents) in sugarcane production at farm level. The following policy package can help

the farmers to improve the sugarcane productivity and its quality:

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 260

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

a) Scientific techniques such as tissue culture farming, etc. must be followed;

b) Recommendations of Mahajan Committee regarding cane area reservation and cane

supply arrangement must be implemented properly (see, Indian Sugar Year Book,

2005/06 for detailed recommendations);

c) Proper irrigation facilities are needed to avoid the impact of rain shortfall on the

sugarcane quality;

d) Timely transportation and crushing of sugarcane is required to attain the maximum

possible sugar recovery from the sugarcane;

e) Contract farming must be encouraged and the contracts between the sugar firms and

the farmers must be for the long-run;

f) Although being less remunerative for sugar firms, statuary minimum price (SMP)

requires continuous upward revision for inducing the farmers to diversify their

production operations towards the production of sugarcane from the production of

indigenous crops wheat and rice;

g) Decisions of government to announce SMP before the start of sowing season should

be rigidly followed;

h) The sugar development funds (SDFs) can be utilized to pay the mounting arrears of

sugarcane payments; and

i) More research and development (R&D) on improving the productivity and quality of

sugarcane is required.

2) To improve the overall technical efficiency, sugar firms are required to improve their

managerial practices. As suggested by the Mahajan Committee (1997) that cooperative

sugar firms are not independent to take quick decision, despite of which the managerial

irregularities have been observed in the operations of these firms. Thus, these firms are

needed to pay back the state equity and provide full autonomy to the managers of these

firms.

3) To mitigate or reduce the extent of technical inefficiency, an improvement in the policy

variable RETURN (a measure of profitability) is mandatory. However, to improve the

profitability of the sugar firms, the following policy measures are recommended:

a) There must be a provision of sanctioning short-term loans from the sugar

development fund (SDF)1 for repaying the mounting arrears of sugarcane. These

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 261

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

short term loans must be mandatory to be repaid in between one sugar year either

through installments or by lump sum payments;

b) The government must purchase the sugar for the levy quota at market prices and

support the public distribution system (PDS) through properly targeted subsidies;

and

c) Easy credit must be available for the rehabilitation of the sugar firms.

4) Diversification of sugar production towards the byproducts of sugar is necessary to

improve the profitability of the sugar firms. The following recommendations of the

High powered committee (Mahajan committee) must be followed:

a) Molasses is a major byproduct of the sugar industry. The estimated sale realization

from molasses by sugar factory is a part of yearly cash inflows of the project. Thus,

sugar firms must diversify their operations towards production of ethanol using

molasses via installing refineries. The ethanol can be sold to the petroleum

companies to execute 10 percent blending program;

b) Sugar firms must install the required machinery to generate and distribute steam

power (i.e., electricity) using bagasse, etc. With the installation of high pressure

boilers with high degree of efficiency, steam consumption in process must be

reduced leading to saving bagasse and the remaining bagasse can be sold to the

industries using it as raw material. Paper industry is one of the industries which can

utilize the bagasse to make paper from it; and

c) The production of bio-fertilizer through mix of spent wash of the distillery with

press mud from sugar mills must be encourage and farmers must be induced to use

such bio-fertilizer. The use of bio-fertilizer is more environment friendly as it

requires less use of water.

5) There is no need to increase the size of production, as the returns-to-scale in all the 12

major sugar producing states don’t found to be significantly different from constant

returns-to-scale (i.e., scale efficiency don’t differ significantly from unity). The need is,

therefore, to utilize existing plant and machinery up to its optimum extent.

6) TFP growth is substantial and statistically significant. However, to achieve the

maximum potential growth of output, a positive inputs growth especially of sugarcane

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 262

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

is required. Thus, the steps given in the first policy implication must be followed to

improve the inputs growth.

In sum, because of inadequate supply of cane and excessive intervention of the government in

fixing the price for both sugar and sugarcane, most of the sugar mills are not operating at full

capacity and exhibiting considerable waste of resources. Further, low levels of profitability and

low sugar recovery from sugarcane add up to the excess capacity and inefficiency in the industry.

Besides this, the licensing policy system followed by the government until 1998 did not permit

the capacity expansion of the existing mills and thus, restricted them to avail economies of scale.

Even after the adoption of delicensing policy of September 1998, the industry is operating under

tightly regulated environment and carries a huge stock of underutilized capital or capacity. The

stiff government control over the sugar firms’ operations hinders their techno-economic

feasibilities and restricts them to expand their capacity per unit. Contrary to this, sugar industry

all over the world has been consolidating and moving towards larger capacity per unit. The

constraints on the capacity expansion and decisions of the government regarding the purchase of

sugar for maintaining buffer stocks and allowing the exports of sugar, further, restrict the sugar

firms to operate on efficiency frontier and limit the growth (i.e., output growth and TFP growth)

of sugar industry.

***************

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 263

Technical Efficiency, Capacity Utilization and Total Factor Productivity Growth in Indian Sugar Industry

ENDNOTES

1

Sugar development fund (SDF) set up under SDF Act, 1982 is funded by transfer of proceeds of sugar cess levied

(Rs.14/-per quintal) and collected under sugar cess act, 1982, on sugar produced in the country. The fund provides

for sanctioning loans to sugar undertakings for rehabilitation of plant and machinery. The fund also provides for

payments of grants to established institutions connected with sugar industry for carrying out research.

Summary, Conclusions and Relevant Policy Implications Page 264

You might also like

- Production and Operations Management at BataDocument45 pagesProduction and Operations Management at BataAastha Grover88% (49)

- 03 - Literature Review PDFDocument8 pages03 - Literature Review PDFSonali mishraNo ratings yet

- Kof Project of Edible Oil IndustryDocument56 pagesKof Project of Edible Oil IndustryNishwith GE0% (1)

- Topic 2.1 Innovation Boosts Growth HWDocument2 pagesTopic 2.1 Innovation Boosts Growth HWkristopher augustin NMSHTVNo ratings yet

- 2BSvs-STD-01-V1.8 - EN - REQUIREMENTS - FOR - VERIFICATION - OF - BIOMASS - PRODUCTION - v1.8 - Validated - v120719 - ENDocument24 pages2BSvs-STD-01-V1.8 - EN - REQUIREMENTS - FOR - VERIFICATION - OF - BIOMASS - PRODUCTION - v1.8 - Validated - v120719 - ENVeronica CamargoNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Hotel IndustryDocument3 pagesEvolution of Hotel IndustrySrinivasan Krishnan 1828543No ratings yet

- Internship ReportDocument56 pagesInternship ReportMuzaffar Ali100% (1)

- Abdul RahemanDocument25 pagesAbdul RahemanAsad AbbasNo ratings yet

- Synopsis AmulDocument8 pagesSynopsis AmulAyush ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Chang 2019Document14 pagesChang 2019Stiven Riveros GalindoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Sugar IndustryDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Sugar Industryefjddr4z100% (1)

- Analyzing The Working Capital Management and Productivity GrowthDocument210 pagesAnalyzing The Working Capital Management and Productivity GrowthAsad IqbalNo ratings yet

- A Study On Growth and Productivity of Indian Sugar CompaniesDocument10 pagesA Study On Growth and Productivity of Indian Sugar CompaniesInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Analysis of Sugar Industry in PakistanDocument15 pagesAnalysis of Sugar Industry in Pakistandj_fr3akNo ratings yet

- Growth and Performance of Food Processing Industry in IndiaDocument10 pagesGrowth and Performance of Food Processing Industry in IndiaThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- 18 Eij March12 Vol1 Issue3Document17 pages18 Eij March12 Vol1 Issue3DrShailendra PatelNo ratings yet

- Capacity Utilization Strategies in The Milk Processing Industry in ZimbabweDocument9 pagesCapacity Utilization Strategies in The Milk Processing Industry in ZimbabweFiqih DaffaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Sugar IndustryDocument7 pagesThesis On Sugar Industryxmlzofhig100% (1)

- 2017 - Total Factor Productivity Analysis in Food Sector - Melati KusumawatiDocument12 pages2017 - Total Factor Productivity Analysis in Food Sector - Melati KusumawatiMelati KusumawatiNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Performance of Sugar Industry Using Regression AnalysisDocument8 pagesSupply Chain Performance of Sugar Industry Using Regression AnalysisVittal SBNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry ReportDocument231 pagesSugar Industry ReportPriyanka Chowdhary100% (1)

- PHD Paper - On Corporate GovernanceDocument19 pagesPHD Paper - On Corporate GovernanceBenson BarazaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Transaction CostDocument383 pagesAnalysis of Transaction CosthjsdNo ratings yet

- Technical Change and Productivity Growth in The Indian Sugar IndustryDocument9 pagesTechnical Change and Productivity Growth in The Indian Sugar IndustryRidho Jinzukyushinobi de PaslandzNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Design of The StudyDocument47 pagesIntroduction and Design of The StudyKarthika ArvindNo ratings yet

- Effect of Production Flexibility On Performance of State-Owned Sugar Companies in Western Region, KenyaDocument7 pagesEffect of Production Flexibility On Performance of State-Owned Sugar Companies in Western Region, KenyaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- IJCRT1812741Document20 pagesIJCRT1812741VIKASH RATHINAVEL K R XII BNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Estimation of Working Capital Reqiurements Krishna Sugar Factory AthaniDocument72 pagesA Project Report On Estimation of Working Capital Reqiurements Krishna Sugar Factory Athanigshetty08_966675801No ratings yet

- Literature Review On Sugar Industry in IndiaDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Sugar Industry in Indiazrpcnkrif100% (1)

- FinalDocument103 pagesFinalazzurocstarNo ratings yet

- THESIS FINAL... Performance Assessment and ImprovementDocument111 pagesTHESIS FINAL... Performance Assessment and ImprovementErmias YihunieNo ratings yet

- Suger Factory 2Document111 pagesSuger Factory 2Manoj Balla100% (1)

- Performance of Fertilizer Industry in India: Dr. Prameela S. Shetty DR - Devaraj K.Document17 pagesPerformance of Fertilizer Industry in India: Dr. Prameela S. Shetty DR - Devaraj K.ganesh joshiNo ratings yet

- KPI Breif - Final (23079) .Docx KpisDocument16 pagesKPI Breif - Final (23079) .Docx Kpiswahid mohdNo ratings yet

- Economic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyDocument6 pagesEconomic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyKrishna KumarNo ratings yet

- Sugar Industry ThesisDocument8 pagesSugar Industry Thesisafcnzcrcf100% (2)

- Iffco ProjectDocument113 pagesIffco ProjectShefali ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Technical Efficiency and Investigation of Efficiency Variables in Wheat Production: A Case of District Sargodha (Pakistan)Document8 pagesEstimation of Technical Efficiency and Investigation of Efficiency Variables in Wheat Production: A Case of District Sargodha (Pakistan)kmillatNo ratings yet

- 13 Synopsis PDFDocument12 pages13 Synopsis PDFBrhanu GebreslassieNo ratings yet

- A PROJECT REPORT ON Ratio Analysis at NIRANI SUGAR LIMITED PROJECT REPORT MBA FINANCEDocument76 pagesA PROJECT REPORT ON Ratio Analysis at NIRANI SUGAR LIMITED PROJECT REPORT MBA FINANCEmoula nawazNo ratings yet

- Estimating Total Factor Productivity and Its Components: Evidence From Major Manufacturing Industries of PakistanDocument25 pagesEstimating Total Factor Productivity and Its Components: Evidence From Major Manufacturing Industries of PakistanSohail HashwaniNo ratings yet

- KPMG Report Exec SummaryDocument19 pagesKPMG Report Exec SummaryNawin KumarNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Budgetary Control at Ranna SugarsDocument69 pagesA Project Report On Budgetary Control at Ranna Sugarsanshul5410No ratings yet

- Financial Performance of Selected Private Sector Sugar Companies in Tamil Nadu - An EvaluationDocument12 pagesFinancial Performance of Selected Private Sector Sugar Companies in Tamil Nadu - An Evaluationramesh.kNo ratings yet

- Optimization Principle and Its Applicati PDFDocument8 pagesOptimization Principle and Its Applicati PDFdian permanaNo ratings yet

- Optimization Principle and Its ApplicatiDocument8 pagesOptimization Principle and Its Applicatiadedejipraize1No ratings yet

- A Project Report On Working Capital Management Nirani Sugars LTDDocument95 pagesA Project Report On Working Capital Management Nirani Sugars LTDBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)100% (4)

- Employees Welfare Facilities - An Opinion Survey at DCW Limited, SahupuramDocument68 pagesEmployees Welfare Facilities - An Opinion Survey at DCW Limited, Sahupuramsarathspark0% (1)

- NavdeepDocument16 pagesNavdeepTripti DuttaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Sugar Industry Competitiveness in PakiDocument16 pagesAnalysis of Sugar Industry Competitiveness in PakiMalikXufyanNo ratings yet

- Technology-Productivity Conundrum in India'S Manufacturing Under Globalization A Preliminary Exploration Using Innovation System PerspectiveDocument25 pagesTechnology-Productivity Conundrum in India'S Manufacturing Under Globalization A Preliminary Exploration Using Innovation System PerspectiveFernando Hernández TaboadaNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument55 pagesProjectamithgouda0% (1)

- Case Analysis of Amul FinalDocument24 pagesCase Analysis of Amul FinalSarabjit Singh100% (1)

- Export Competitiveness and Concentration Analysis of Major Sugar Economies With Special Reference To IndiaDocument29 pagesExport Competitiveness and Concentration Analysis of Major Sugar Economies With Special Reference To IndiaRicardo de Queiroz MachadoNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance of Sugar Mills in East Java: A Transaction Cost Economics PerspectiveDocument17 pagesCorporate Governance of Sugar Mills in East Java: A Transaction Cost Economics PerspectiveFajrinNo ratings yet

- ITC - Aashirvaad Atta: A Project Report ONDocument8 pagesITC - Aashirvaad Atta: A Project Report ONsuvendu08No ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument13 pagesSynopsisShobhit SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Habtamu 2MSPM2 - Strategic IndividualDocument7 pagesHabtamu 2MSPM2 - Strategic IndividualHabtamu DessisaNo ratings yet

- Amul - Sumit GuptaDocument57 pagesAmul - Sumit Guptadjsumit11No ratings yet

- Market Structure, Conduct and Performances of Some Selected Large and Medium Scale Food Manufacturing CompaniesDocument94 pagesMarket Structure, Conduct and Performances of Some Selected Large and Medium Scale Food Manufacturing Companiessociology7No ratings yet

- Comprehensive Project Report: Indian Sugar IndustryDocument54 pagesComprehensive Project Report: Indian Sugar IndustryDivya VishwanadhNo ratings yet

- Policies to Support the Development of Indonesia’s Manufacturing Sector during 2020–2024: A Joint ADB–BAPPENAS ReportFrom EverandPolicies to Support the Development of Indonesia’s Manufacturing Sector during 2020–2024: A Joint ADB–BAPPENAS ReportNo ratings yet

- 20240412113841-004ugb-com-2nd4th6thsemesterexaminationmay2024Document2 pages20240412113841-004ugb-com-2nd4th6thsemesterexaminationmay2024Bipasha ShahNo ratings yet

- Micro PPT DocumentDocument27 pagesMicro PPT DocumentBipasha ShahNo ratings yet

- Money and BankingDocument7 pagesMoney and BankingBipasha ShahNo ratings yet

- Economical Impact of Covid-19Document3 pagesEconomical Impact of Covid-19Bipasha ShahNo ratings yet

- Essay Writing CompetitionDocument3 pagesEssay Writing CompetitionBipasha ShahNo ratings yet

- ACYCST Cost Accounting Quiz ReviewerDocument123 pagesACYCST Cost Accounting Quiz ReviewerelelaiNo ratings yet

- Quesada CleanersDocument3 pagesQuesada CleanersAngel EstradaNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Canadian 7th Edition Abel Solutions ManualDocument22 pagesMacroeconomics Canadian 7th Edition Abel Solutions Manualmabelleonardn75s2100% (35)

- Iso 22000Document5 pagesIso 22000DUOMO INDUSTRIANo ratings yet

- Student Calendar 2nd 9 Wks 2022-23Document2 pagesStudent Calendar 2nd 9 Wks 2022-23Broken Eye StudiosNo ratings yet

- Mapa NeivaDocument16 pagesMapa NeivaPaulaNo ratings yet

- Pemetaan BDDocument17 pagesPemetaan BDNaurelNo ratings yet

- Internship Report For Accounting and FinDocument28 pagesInternship Report For Accounting and FinHãmèéž MughalNo ratings yet

- EDE Assingment 9Document3 pagesEDE Assingment 9jhon cenaNo ratings yet

- Chapter I Preliminary Chapter - Policies - TermsDocument6 pagesChapter I Preliminary Chapter - Policies - TermsLawStudent101412No ratings yet

- Project1 3Document89 pagesProject1 3eyob yohannes100% (1)

- Catalog SanzDocument55 pagesCatalog SanzGotlem BordNo ratings yet

- Principles of Microeconomics Canadian 6th Edition Mankiw Test BankDocument25 pagesPrinciples of Microeconomics Canadian 6th Edition Mankiw Test BankAustinSmithpdnq100% (41)

- PDF GM 1927 16b Tiered Supplier Process AuditDocument5 pagesPDF GM 1927 16b Tiered Supplier Process AuditrgeNo ratings yet

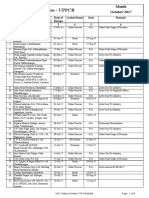

- NOC Status - UPPCB: Month October 2017Document6 pagesNOC Status - UPPCB: Month October 2017Jeevan jyoti vnsNo ratings yet

- The Letter of Refund-0410 230525 124603Document6 pagesThe Letter of Refund-0410 230525 124603hariyono. jaguarNo ratings yet

- Clat Monthly Digest October 2021 Eng 80Document36 pagesClat Monthly Digest October 2021 Eng 80Soubhik MondalNo ratings yet

- Reforms Claimed by Provincial BOIs - Oct 219, 2020Document37 pagesReforms Claimed by Provincial BOIs - Oct 219, 2020Naeem AhmedNo ratings yet

- What Makes Maruti Suzuki Stand Out 4 1Document7 pagesWhat Makes Maruti Suzuki Stand Out 4 1api-712012542No ratings yet

- Catering Services ProjectDocument7 pagesCatering Services ProjectillaNo ratings yet

- Dev Phil 1Document102 pagesDev Phil 1EyegateNo ratings yet

- Julian L. Simon: Science, New Series, Vol. 208, No. 4451. (Jun. 27, 1980), Pp. 1431-1437Document9 pagesJulian L. Simon: Science, New Series, Vol. 208, No. 4451. (Jun. 27, 1980), Pp. 1431-1437fizaAhaiderNo ratings yet

- Dubai Consultant List PDFDocument12 pagesDubai Consultant List PDFpalva1225% (4)

- Domestic Gas Delivery Regulations 2022 PDF 1Document15 pagesDomestic Gas Delivery Regulations 2022 PDF 1AmaksNo ratings yet

- ABB CABLE GLANDS CATALOGUE - LATEST AW - June 2019Document140 pagesABB CABLE GLANDS CATALOGUE - LATEST AW - June 2019julpian tulusNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Poultry FarmingDocument17 pagesBusiness Plan Poultry FarmingMwesigwa DaniNo ratings yet

- Case Study 3: Value-Based Leadership For ChangeDocument13 pagesCase Study 3: Value-Based Leadership For ChangeTruc ThanhNo ratings yet