Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Puerto Rico Pays Heavily For Mainland's Recession - The New York Times

Puerto Rico Pays Heavily For Mainland's Recession - The New York Times

Uploaded by

Félix Santiago-MartínezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Puerto Rico Pays Heavily For Mainland's Recession - The New York Times

Puerto Rico Pays Heavily For Mainland's Recession - The New York Times

Uploaded by

Félix Santiago-MartínezCopyright:

Available Formats

GIVE THE TIMES Account

ADVERTISEMENT

PracticeFrench PracticeGerman PracticeItalian

PracticeSpanish PracticePortuguese †Babbel

Puerto Rico Pays Heavily For

Mainland's Recession

Share full article

By Michael Stern Special to The New York Times

March 22, 1975

See the article in its original context from

March 22, 1975, Page 1 Buy Reprints

VIEW ON TIMESMACHINE

TimesMachine is an exclusive benefit for home

delivery and digital subscribers.

The New York Times Archives

About the Archive

This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the

start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally

appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them.

Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other

problems; we are continuing to work to improve these archived versions.

SAN JUAN, P. R., March 21 —Puerto Rico is importing a massive

dose of the United States recession, and paying for it is forcing

equally massive austerities on the people and Government of this

sunny, productive but deeply troubled island commonwealth.

Yesterday, Gov. Rafael Hernandez Colon sent a 1975–76 budget of

$1.3-billion to the Legislature. The budget is designed to bring

spending in line with falling income by withholding $100 - million in

scheduled pay increases from public employes and imposing $94-

million in further cuts on every department of Government.

These measures come on top of a tax surcharge that was imposed

retroactively on 1974 incomes, a 5 per cent excise on all imports

except food and the dismissal of 1,600 Government employes,

actions taken to close a $200-million deficit opened by recession

and inflation in this year's budget of $1.5-billion.

Two days ago, in a San Juan supermarket, Mrs. Emilio Bonilla, wife

of an out-of-work plumber, began to cry after she slapped her 3-

year-old son for opening an 88-cent bag of cookies she had not

meant to buy.

ADVERTISEMENT

ALICE & JACK starring Andrea Riseborough

and Domhnall Gleeson starting March 17.

Are the bonds between them stronger than the

forces that would tear them apart? Explore the

complexities of modern love. Stream on the

PBS app starting March 17.

STREAM ON PBS

“Look,” she told the manager when he asked what was wrong.

“That's what I have for a whole week for four of us.” Her

outstretched hand held crumpled bills and change adding up to

$7.52. Then she blushed with shame, picked up her son and ran out

of the store.

Mrs. Bonilla's husband is one of the 149,000 islanders who, were

officially counted as unemployed in January, a total that produced

an unadjusted jobless rate of 17.1 per cent, almost double the United

States rate of 9.0 per cent. The real rate, when the long-termed

unemployed who have given up looking for work are counted in, is

variously estimated at from 22 to 35 per cent.

For the jobless and for the working population, inflation is

widening the usual 25-per-cent difference between mainland and

island prices. Puerto Ricans pay $1.22 for a dozen grade-A large

eggs, $1.59 for a pound of hamburger meat, 65 cents for a two-

pound package of flour and $1.92 for the five-pound bag of sugar

that was refired here from cane grown on the island's plantations.

These public and private troubles are making many Puerto Ricans

question the assumption of “Fomento,” the development program

that in 25 years has transformed Puerto Rico's poor agricultural

economy into a relatively prosperous industrial society.

The reassessment is prompted by the realization that

industrialization has tied Puerto Rico as closely to the mainland

business cycle as New York, Michigan and California are tied to it.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ninety-eight percent of all the food, raw materials and

manufactured goods consumed here are imported from the

mainland and 85 per cent of the island's exports go to the

mainland.

Interviews with Government officials, labor leaders, businessmen

and bankers revealed a broad consensus that Puerto Rico would

not pull out of its slump until the United States pulled out of its

recession, and may even lag behind the mainland upturn predicted

for later this year. The realization has been a sabering one, because

the turndown here comes after 10 years of steady growth that was

hardly even slowed by the 1969–70 United States recession.

Incomes in Puerto Rico have been rising, though they are still well

below United States levels. The average weekly wage at the start

of this year was $81.50.

Nevertheless, the pattern of migration in recent years has been

toward the island from the mainland. In 1972, 33,596 more people

came here than left. In 1973, the net inflow rose to 34,492. Last year,

the net inflow fell to 18,378, but officials of the Puerto Rican

Planning Board, who compile the figures, say they cannot relate

the drop to the heavier impact of the recession here.

Tomento' Is Questioned

Average Income $81.50

Though half the population; of three million lives in metropolitan

San Juan, industry is scattered throughout the island. Jose Rivera

Janer, deputy director of Fomento, points out that when a factory

closes in a small town, the effect on the population can be

disastrous.

ADVERTISEMENT

He cited the closing last year of the Fibers International plant of

Phillips Petroleum in the town of Guayama, which put 2,300 people

out of work. “When you consider that three other jobs depended on

every job in the fibers factory, you can see what this meant for a

town of 36.000 people,” Mr. Rivera said. “It is a real crisis, a

depression on a local level, and it has happened elsewhere.”

From last June to February of this year, 53 enterprises sponsored

by Fomento have closed. But Mr. Rivera said that new enterprises

were still being created. completed arrangements for 175 new

plants to open on the island, with a potential of 9,000 new jobs. For

the comparable period in 1973–74, the figures were 200 new

enterprises with a potential of 11,000 jobs.

In the same months Fomento

Among the companies setting up here are Hoffman-LaRoche, Inc.

the Swiss pharmaceutical concern, which is investing $50-million

in a plant to pro duce tranquillizers with a work force of 300.

“These figures show that the recession has slowed our job creation

efforts, but it has not stopped them,” Mr, Rivera said.

The principal lure Fomento uses is exemption from all taxes for

from 10 to 30 years. depending on where a company settles. In

addition, it offers grants for installing new machinery, job training

and factory buildings at rents of 75 cents to $1.75 a square foot.

ADVERTISEMENT

To revive recession-slowed interest in the island, Governor

Hernandez Colon has liberalized the incentive package with a 25

per cent wage subsidy. It will be offered to companies that open

plants with 500 employes or more and keep the plants working for

at least two years.

This proposal has been attacked privately by some former

Fomento officials as too liberal and publicly by Carlos Romero

Barcelo, the mayor of San Juan, as self-defeating.

“Such programs are like quicksand,” Mr. Romero said “The deeper

we get into them, the harder it will be to get out of them. A

company that doesn't pay taxes has no feeling of belonging to the

community, and in the long run it will do Puerto Rico no good.”

Mr. Romero, a leader of the New Progressive party, is expected to

run against the Governor, a Popular Democrat, in the election next

year.

“What has been the result of all these tax incentives,” Mr. Romero

asked in an interview. “Companies come in, but when the tax

incentive ends. they move away. They don't bring any permanent

good to the island. And they [the programs) create cross conflict

and feelings of jealousy because they are not offered to native

businesses.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Fomento officials conceded that some companies, principally

apparel companies with low capital investment, had moved away

after their tax exemptim ended. But they insist that most of the

2,000 factories estab. lished here under Fomento auspices have

remained and have earned new exemptions by creating new

product lines i?? new factories.

Investment Incentives

Some Moved

Juan Albors. the Commonwealth Secretary of State, save the

exemptions co remove from the tax base enterprises that

elsewhere help to defray the cost of government. But without them,

he said, there would be no reason for many mainland companies to

set up here. And the jobs and economic activity created by the new

enterprises bring in other tax revenues that the commonwealth

would not have had.

The Government's principal sources of income are the income tax,

real estate levies and the excise on imported goods and raw

materials. Recession dropped the yield of these revenues sharply

last year and at the same time inflation and the rising cost of

imported oil increased expenditures.

“Our budget problem here was fundamentally the same that faced

many state governments on the mainland,” Mr. Albors said. “And

the measures we have adopted are similar to those they are

taking.” The surtax has been enacted for 1974 incomes and for 1975

and 1976 as well. It is sharply graduated, rising from 1 per cent on

net taxable incomes of $1,000 or less, to 5 per cent incomes of

$12,000 or more.

Mr. Albors said that the Government hoped that much of the $94-

million in new cuts in the 1975–76 budget could be avoided if more

Federal aid were appropriated by Congress.

ADVERTISEMENT

“But if such aid doesn't happen,” he said, “every department is on

warning that it will have to achieve economies the best way it can.”

The new budget makes no provision for an additional $48-million in

oil costs anticipated as a result of an order from the Environmental

Protection Agency in Washington to the power au thority here to

start burning more expensive low - sulphur fuel oil. The

commonwealth has appealed to E.P.A. officials in Washington to

delay implementation of the order, which was issued this week.

While the Government proceeds with its austerity program,

opposition is mounting. The Teachers Federation has threatened

selective strikes to force payment of the wage increases that have

been rescinded. And the small Puerto Rican Socialist Party has

begun holding railies in many cities to urge people not to pay the

higher income tax.

Here in San Juan the tourist season is ending, with gaiety among

visitors but gloom among the hotel keepers. The recession and a

70-per-cent increase in air fares from the mainland has dropped

hotel occupancy this season 16.7 per cent below the record level

last year and the number of visitors has fallen 8.1 per cent.

Assessing the future, Hector Ledesma, executive vice president of

the island's largest bank sees a bright tomorrow for Puerto Rico

once the recession is past.

“We have the potential here to become the distributive center for

the whole of the Caribbean.” he said. “And we also can become the

financial capital, serving those companies and needs that are too

small to interest Wall Street and New York.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The bank, which has assets of $1.02-billion and ranks 101st among

the 1,400 banks of the United States, hopes to play a major role in

the future development of the island. A change in the tax law

permitting mainIland and foreign companies to keep interest

earned on profits on deposit in Puerto Rican banks without paying

tax on the interest may increase bank funds here by $100-to-$200-

million.

“When that money is invested in our economy,” Mr. Ledesma said,

“we can expect a lot more growth.”

Banker Foresees Progress

Share full article

ADVERTISEMENT

NEW More to Discover Expand to see more

© 2024 The New York Times Company NYTCo Contact Us Accessibility Work with us Advertise T Brand Studio Your Ad Choices Privacy Policy Terms of Service Terms of Sale Site Map Help Subscriptions

You might also like

- NYT v. OpenAIDocument69 pagesNYT v. OpenAITHR100% (1)

- Keep An Eye On This Guy' - Inside Eric Adams's Complicated Police CarDocument1 pageKeep An Eye On This Guy' - Inside Eric Adams's Complicated Police Caredwinbramosmac.comNo ratings yet

- James Burke: A Career in American Business (A&B)Document5 pagesJames Burke: A Career in American Business (A&B)Foram ThakkarNo ratings yet

- Marketing Assignment Coca-Cola Great Britain Repaired)Document44 pagesMarketing Assignment Coca-Cola Great Britain Repaired)Hope Romain100% (1)

- G Michael Killenberg Auth Public PDFDocument382 pagesG Michael Killenberg Auth Public PDFCas NascimentoNo ratings yet

- The Important Role of Newspaper and Magazines in Our LivesDocument5 pagesThe Important Role of Newspaper and Magazines in Our LivesAndrew Ranjith100% (3)

- Coastal Vision DocumentDocument20 pagesCoastal Vision DocumentaxlmartinoNo ratings yet

- Help Times Journalists Uncover The Next Big StoryDocument1 pageHelp Times Journalists Uncover The Next Big Storyed2870winNo ratings yet

- Nestle-1 FUL Project ReportDocument29 pagesNestle-1 FUL Project ReportSadiaSaeed90No ratings yet

- CH 28Document27 pagesCH 28J.JEFRI CHENNo ratings yet

- Library Economics Presentation April 2018Document20 pagesLibrary Economics Presentation April 2018Lonnie GambleNo ratings yet

- Austerity Recent HistoryDocument220 pagesAusterity Recent Historyqiaoxin136100% (2)

- The Grace TimesDocument1 pageThe Grace TimeslilmizzsmartypantzNo ratings yet

- The Real Meaning of The Merger Boom (P.Drucker 1999)Document6 pagesThe Real Meaning of The Merger Boom (P.Drucker 1999)Bij Lobith... | Omdat meedenken er toe doet100% (2)

- Great Depression Completed NotesDocument7 pagesGreat Depression Completed Notesxczq5gqwwhNo ratings yet

- Great DepressionDocument31 pagesGreat Depression晨航 凌No ratings yet

- Great Depression - What Happened, Causes, How It EndedDocument4 pagesGreat Depression - What Happened, Causes, How It EndedAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- Reagan Cheat SheetDocument4 pagesReagan Cheat Sheetsxnxyqureshi05No ratings yet

- DollDocument4 pagesDollFredy CastellaresNo ratings yet

- Nestle JamDocument27 pagesNestle JamMuhammad Jawad Asif33% (3)

- Why Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?Document43 pagesWhy Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Why Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?Document43 pagesWhy Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?RaghuPatilNo ratings yet

- Group 2 - Fiscal Policymaking FinalDocument53 pagesGroup 2 - Fiscal Policymaking FinalIVY CAPITONo ratings yet

- Johnson and Johnson-Tylenol Case: Team CocoonDocument20 pagesJohnson and Johnson-Tylenol Case: Team Cocoonmanish yadavNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy: The Keynesian View and Historical PerspectiveDocument51 pagesFiscal Policy: The Keynesian View and Historical PerspectiveGvantsa MorchadzeNo ratings yet

- The Great Retail Bifurcation: Why The Retail "Apocalypse" Is Really A RenaissanceDocument24 pagesThe Great Retail Bifurcation: Why The Retail "Apocalypse" Is Really A RenaissanceTincho PreitiNo ratings yet

- Cerveza ToastDocument14 pagesCerveza ToastXiomara Betzabé Yarasca AraujoNo ratings yet

- Eei 6-7-8-9Document6 pagesEei 6-7-8-9luciaNo ratings yet

- Relate Text Context To Particular Social IssuesDocument16 pagesRelate Text Context To Particular Social IssuesKrystalle Mirah CasawayNo ratings yet

- Makiw AD-ASDocument25 pagesMakiw AD-ASpalakagarwal.xccNo ratings yet

- Mitroff 1987Document12 pagesMitroff 1987iBooqNo ratings yet

- Princ ch23 Presentation PDFDocument19 pagesPrinc ch23 Presentation PDFنور عفيفهNo ratings yet

- Great Depression Begins - Chapter SummaryDocument1 pageGreat Depression Begins - Chapter Summaryapi-332186475No ratings yet

- Agriculture: A Value Culture ForDocument12 pagesAgriculture: A Value Culture ForTin DanNo ratings yet

- Reaganomics Explained 2Document14 pagesReaganomics Explained 2dominicxander59No ratings yet

- Keynisian Ecomomic...Document14 pagesKeynisian Ecomomic...Misha KosiakovNo ratings yet

- Keep The Cap: Why A Tax Increase Will Not Save Social Security, Cato Briefing Paper No. 93Document12 pagesKeep The Cap: Why A Tax Increase Will Not Save Social Security, Cato Briefing Paper No. 93Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- The Next Consumer Recession: Preparing NowDocument22 pagesThe Next Consumer Recession: Preparing NowPanther MelchizedekNo ratings yet

- My Company Is Subsidiary Company Under The ConglomerateDocument15 pagesMy Company Is Subsidiary Company Under The Conglomerateashley0902No ratings yet

- Macroeconomics - ppt1 T41AAnQ0FLDocument47 pagesMacroeconomics - ppt1 T41AAnQ0FLAshutosh BiswalNo ratings yet

- Biofuels Slideshow 2Document35 pagesBiofuels Slideshow 2Environmental Working Group100% (2)

- Robinson On The Problem of Full EmploymentDocument40 pagesRobinson On The Problem of Full EmploymentjorgecierzoNo ratings yet

- House Evacuation Plan: Bedroom 1 Bedroom 2 Bedroom 3Document3 pagesHouse Evacuation Plan: Bedroom 1 Bedroom 2 Bedroom 3Rausa MaeNo ratings yet

- Accelerating Out of The Great Recession Rhodes eDocument5 pagesAccelerating Out of The Great Recession Rhodes elynnvilleNo ratings yet

- Jgletter All 3q09Document14 pagesJgletter All 3q09ZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Ap EconDocument15 pagesChapter 1 Ap Econcordovajohnrolly1No ratings yet

- The New Deal How Successful Was It-Reading OnlyDocument1 pageThe New Deal How Successful Was It-Reading OnlyJolly BNo ratings yet

- Business Communication 2.0/Winter09/COMPANY DATA MATRIX: Non-Food Food, Housew Ar E, Clo ThingDocument6 pagesBusiness Communication 2.0/Winter09/COMPANY DATA MATRIX: Non-Food Food, Housew Ar E, Clo ThingSUNXIAOCHENGNo ratings yet

- Ogilvy Making Brands Matter in Turbulent Times Beyond COVID 19 Version 2.0Document35 pagesOgilvy Making Brands Matter in Turbulent Times Beyond COVID 19 Version 2.0chiranjeeb mitraNo ratings yet

- SOCSCI4 ReviewerDocument10 pagesSOCSCI4 ReviewerQwerty TyuNo ratings yet

- Economic RationaleDocument31 pagesEconomic RationaleJhem SuetosNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MacroeconomicsDocument6 pagesIntroduction To MacroeconomicsDayangku AyusapuraNo ratings yet

- 3: Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development: Dr. Jaap Van Baars Spring 2022Document36 pages3: Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development: Dr. Jaap Van Baars Spring 2022samNo ratings yet

- Exxon Valdez Oil Spill CaseDocument3 pagesExxon Valdez Oil Spill CaseGodfreyAlemao100% (1)

- WhirlpoolDocument7 pagesWhirlpoolSabyasachi ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- The - Hyperinflation - Survival.guide - Gerald - Swanson PDFDocument106 pagesThe - Hyperinflation - Survival.guide - Gerald - Swanson PDFNorisNo ratings yet

- Micro Vs Macro Economics Circular Flow of Income DepressionDocument15 pagesMicro Vs Macro Economics Circular Flow of Income DepressionSai harshaNo ratings yet

- Argentina Economic CrisisDocument11 pagesArgentina Economic Crisisgabriel.cordeiroNo ratings yet

- Microeconomic AnalysisDocument32 pagesMicroeconomic AnalysisAbdin AshrafNo ratings yet

- The New Era of Wealth: How Investors Can Profit From the 5 Economic Trends Shaping the FutureFrom EverandThe New Era of Wealth: How Investors Can Profit From the 5 Economic Trends Shaping the FutureNo ratings yet

- Plunder and Blunder: The Rise and Fall of the Bubble EconomyFrom EverandPlunder and Blunder: The Rise and Fall of the Bubble EconomyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- From Kitchen to Consumer: The Entrepreneur's Guide to Commercial Food PreparationFrom EverandFrom Kitchen to Consumer: The Entrepreneur's Guide to Commercial Food PreparationRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- John Kenneth Galbraith: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESFrom EverandJohn Kenneth Galbraith: Selected Summaries: SELECTED SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Frantz Fanon's Conflicted Vision For Decolonization - The New RepublicDocument2 pagesFrantz Fanon's Conflicted Vision For Decolonization - The New RepublicFélix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- Count, Explain, RememberDocument1 pageCount, Explain, RememberFélix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- From Middle Class To Petit Bourgeoisie: Cold War Politics and Classed Radicalization in Bogotá, 1958-19721Document33 pagesFrom Middle Class To Petit Bourgeoisie: Cold War Politics and Classed Radicalization in Bogotá, 1958-19721Félix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- "Land To The Original Owners": Rethinking The Indigenous Politics of The Bolivian Agrarian ReformDocument39 pages"Land To The Original Owners": Rethinking The Indigenous Politics of The Bolivian Agrarian ReformFélix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- Downloaded From Http://read - Dukeupress.edu/hahr/article-Pdf/79/2/269/714972/0790269.pdf by Guest On 20 January 2021Document39 pagesDownloaded From Http://read - Dukeupress.edu/hahr/article-Pdf/79/2/269/714972/0790269.pdf by Guest On 20 January 2021Félix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- Writing Positive, Negative and Persuasive MessagesDocument12 pagesWriting Positive, Negative and Persuasive MessagesRaj MehtaNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-510721718No ratings yet

- MUN Research BinderDocument2 pagesMUN Research BindersemaNo ratings yet

- A Tactical Guide To Science Journalism Lessons From The Front Lines Ashley Smart Full ChapterDocument51 pagesA Tactical Guide To Science Journalism Lessons From The Front Lines Ashley Smart Full Chapterricky.basbas197100% (10)

- Rhetorical Summary For Choosing Death by Nicholas D KristofDocument4 pagesRhetorical Summary For Choosing Death by Nicholas D Kristofapi-237087046No ratings yet

- Project 3 PDFDocument12 pagesProject 3 PDFManoj KarthickNo ratings yet

- Who Rules AmericaDocument8 pagesWho Rules AmericaÁngel Ribes CampoyNo ratings yet

- Dual Transformation: Two Routes To Resilience I Clark G. Gilbert President and Ceo @clarkgilbertDocument15 pagesDual Transformation: Two Routes To Resilience I Clark G. Gilbert President and Ceo @clarkgilbertjasson44No ratings yet

- International Herald TribuneDocument23 pagesInternational Herald Tribuneapi-20755710100% (1)

- Badminton's New Dress Code Is Being Criticized As Sexist: Sections SearchDocument13 pagesBadminton's New Dress Code Is Being Criticized As Sexist: Sections SearchJohn Paul MirafloresNo ratings yet

- Voters Doubt Biden's Leadership and Favor Trump, Times - Siena PollDocument1 pageVoters Doubt Biden's Leadership and Favor Trump, Times - Siena Polled2870winNo ratings yet

- Newspapers in AmericaDocument7 pagesNewspapers in AmericaИрина ШтефанNo ratings yet

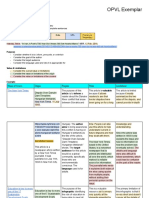

- OPVL ExemplarDocument3 pagesOPVL ExemplarMikeNo ratings yet

- Zionist Media Domination:: The Jewish Suicide Bomber Thatt You Never Heard OffDocument9 pagesZionist Media Domination:: The Jewish Suicide Bomber Thatt You Never Heard OffResearchingPub0% (1)

- Dec7.2011.Federal - motionJudicialNotice+SummaryJudgement NWSDocument188 pagesDec7.2011.Federal - motionJudicialNotice+SummaryJudgement NWSlen_starnNo ratings yet

- A Circle of DistortionDocument20 pagesA Circle of DistortionfinityNo ratings yet

- 2001 Annual ReportDocument76 pages2001 Annual Reporttokumaunity2No ratings yet

- Crown Publishing Group Catalog - Summer 2011Document247 pagesCrown Publishing Group Catalog - Summer 2011Crown Publishing GroupNo ratings yet

- Captura de Tela 2020-04-09 À(s) 07.57.41 PDFDocument54 pagesCaptura de Tela 2020-04-09 À(s) 07.57.41 PDFandreNo ratings yet

- Raising A Moral ChildDocument6 pagesRaising A Moral Child5703918bNo ratings yet

- 000 Full Spring 2016 IssueDocument96 pages000 Full Spring 2016 IssueKNo ratings yet

- The Agony of The Digital TeaseDocument16 pagesThe Agony of The Digital Teasetigerlo75No ratings yet

- Worksheet 1: Editorial Writers and Editors FDocument3 pagesWorksheet 1: Editorial Writers and Editors FWashington City PaperNo ratings yet

- The New York Times 2016-11-07Document70 pagesThe New York Times 2016-11-07stefano100% (1)

- Follow A Career Passion - Let It Follow You - NYTimesDocument2 pagesFollow A Career Passion - Let It Follow You - NYTimesBharath AkellaNo ratings yet

- Amusing Ourselves To DeathDocument4 pagesAmusing Ourselves To Deathapi-549248403No ratings yet