0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views58 pagesGroup 1 - Chapters 5-7

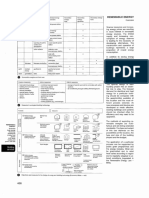

The document discusses tropical design principles for green buildings, focusing on building shape, near-building features, and the outer envelope. Key elements include optimal building shapes for energy efficiency, the importance of overhangs and solar panels for environmental performance, and the role of the building facade in energy use. It emphasizes the integration of sustainable practices in architectural design to enhance energy efficiency and environmental impact.

Uploaded by

Martin NavarrozaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

38 views58 pagesGroup 1 - Chapters 5-7

The document discusses tropical design principles for green buildings, focusing on building shape, near-building features, and the outer envelope. Key elements include optimal building shapes for energy efficiency, the importance of overhangs and solar panels for environmental performance, and the role of the building facade in energy use. It emphasizes the integration of sustainable practices in architectural design to enhance energy efficiency and environmental impact.

Uploaded by

Martin NavarrozaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd