0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views67 pagesModule 2 Part 2

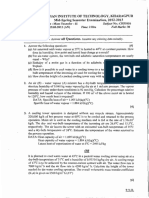

The document outlines the historical development and key concepts of quantum chemistry, including Bohr's atomic model, the de Broglie wavelength, and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. It discusses the evolution of quantum mechanics, the structure of the atom, and the implications of the Bohr model on atomic behavior and emission spectra. Additionally, it highlights the dual nature of electromagnetic radiation and its significance in understanding atomic and subatomic phenomena.

Uploaded by

himanshu2005nathCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views67 pagesModule 2 Part 2

The document outlines the historical development and key concepts of quantum chemistry, including Bohr's atomic model, the de Broglie wavelength, and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. It discusses the evolution of quantum mechanics, the structure of the atom, and the implications of the Bohr model on atomic behavior and emission spectra. Additionally, it highlights the dual nature of electromagnetic radiation and its significance in understanding atomic and subatomic phenomena.

Uploaded by

himanshu2005nathCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd