Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1

Uploaded by

Jeremiah Miko Lepasana100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

177 views42 pagesOriginal Title

Diplomacy is the art and practice of conducting lecture 1.ppt

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

177 views42 pagesDiplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1

Uploaded by

Jeremiah Miko LepasanaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 42

Diplomacy

is the art and practice of

conducting negotiations

between

representatives of

groups or nations.

It usually refers to international

diplomacy, the conduct of

international relations through the

intercession of professional diplomats

with regard to issues of peace-

making, culture, economics, trade and

war. International treaties are usually

negotiated by diplomats prior to

endorsement by national politicians.

The name comes from the

Greek language, and roughly

means "(having) double eyes"

(suggesting that a negotiator's

main attribute should be the

ability to undestand the

interests of all participants).

Diplomats and diplomatic

missions

A diplomat is someone

involved in diplomacy; the

collective term for a group of

diplomats from a single

country is a diplomatic

mission.

An ambassador is the most

senior diplomatic rank; a

diplomatic mission headed by

an ambassador is known as

an embassy. The collective

body of all diplomats resident

in a particular country is

called a diplomatic corps

Diplomacy and espionage

Diplomacy is closely linked to

espionage. Embassies are bases for

both diplomats and spies, and some

diplomats are essentially openly-

acknowledged spies. For instance,

the job of military attachés includes

learning as much as possible about

the military of the nation to which they

are assigned. They do not try to hide

this role and, as such, are only invited

to events allowed by their hosts, such

as military parades or air shows.

There are also deep-cover spies operating

in many embassies. These individuals are

given fake positions at the embassy, but

their main task is to illegally gather

intelligence, usually by coordinating spy

rings of locals or other spies. For the most

part, spies operating out of embassies

gather little intelligence themselves and

their identities tend to be known by the

opposition. If discovered, these diplomats

can be expelled from an embassy, but for

the most part counter-intelligence agencies

prefer to keep these agents in situ and

under close monitoring

The information gathered by spies

plays an increasingly important role

in diplomacy. Arms-control treaties

would be impossible without the

power of reconnaissance satellites

and agents to monitor compliance.

Information gleaned from espionage

is useful in almost all forms of

diplomacy, everything from trade

agreements to border disputes.

Diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition is an important

factor in determining whether a nation is an

independent state. Receiving recognition is

often difficult, even for countries which are

fully sovereign. For many decades after

becoming independent, even many of the

closest allies of the Kingdom of the

Netherlands refused to grant it full

recognition. Today there are a number of

independent entities without widespread

diplomatic recognition, most notably the

Republic of China on Taiwan.

Since the 1970's, most nations have stopped

officially recognizing the ROC's existence on

Taiwan, at the insistence of the People's Republic

of China. Currently, the United States and other

nations maintain informal relations through de facto

embassies, with names such as the American

Institute in Taiwan. Similarly, Taiwan's de facto

embassies abroad are known by names such as

the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative

Office. This was not always the case, with the US

maintaining official diplomatic ties with Taiwan until

1979, when these relations were broken off as a

condition for establishing official relations with

China.

Informal diplomacy

Informal diplomacy (sometimes called Track II

diplomacy) has been used for centuries to

communicate between powers. Most diplomats work

to recruit figures in other nations who might be able

to give informal access to a county's leadership. In

some situations, such as between the United States

and the People's Republic of China, a large amount

of diplomacy is done through semi-formal channels

using interlocutors such as academic members of

thinktanks. This occurs in situations where

governments wish to express intentions or to

suggest methods of resolving a diplomatic situation,

but do not wish to express a formal position.

Track II diplomacy is a specific kind of

informal diplomacy, in which non-officials

(academic scholars, retired civil and military

officials, public figures, social activists)

engage in dialogue, with the aim of conflict

resolution, or confidence-building.

Sometimes governments may fund such

Track II exchanges. Sometimes the

exchanges may have no connection at all

with governments, or may even act in

defiance of governments; such exchanges

are called Track III.

Diplomatic law is that area of

international law that governs

permanent diplomatic missions . A

fundamental concept of diplomatic

law is that of diplomatic immunity,

which derives from state immunity.

An important treaty with regards to

diplomatic law is the 1961 Vienna

Convention on Diplomatic

Relations.

Diplomatic rank

The system of diplomatic rank has over time

been formalised on an international basis.

Traditional diplomacy

Until the early 19th Century, each European

nation had its own system of diplomatic rank.

The relative ranks of diplomats from different

nations had been a source of considerable

dispute, made more so by the insistence of

major nations to have their diplomats ranked

higher than those of minor nations, to be

reflected in such things as table seatings.

In an attempt to resolve the problem, the

Congress of Vienna of 1815 formally established

an international system of diplomatic ranks. The

four ranks within the system were:

1. Ambassador Extraordinary and

Plenipotentiary, or simply Ambassador, who is a

representative of the head of state. Equivalent,

and in some traditions primus inter pares, is the

Papal nuncio. Amongst Commonwealth countries,

the equivalent title High Commissioner (who

represents the government rather than the head

of state) is normally used instead.

A diplomatic mission headed by an

ambassador would be known as an

Embassy; one headed by a High

Commissioner is called a High Commission.

An ambassador and a high commissioner

are entitled to use the title "His/Her

Excellency" from the government and the

people of the country they are appointed to.

If an ambassador or high commissioner that

are from Canada are not addressed by

Canadians as Excellency, but are called

ambassador or high commissioner.

2. Minister Plenipotentiary (in full Envoy

Extraordinary and Minister

Plenipotentiary), or simply Envoy. Usually

just referred to as a Minister, an envoy is a

diplomatic representative with

plenipotentiary powers (i.e. full authority to

represent the head of state), but ranking

below an Ambassador. Where Embassies

are headed by Ambassadors, Legation]s

are headed by Ministers.

3. Minister Resident or Resident Minister, or

simply Minister, is the, now extremely rare, lowest

rank of full diplomatic mission chief, only above

Chargé d'affaires (who is considered an

extraordinary substitute).

Note that both the Minister Plenipotentiary and the

Minister Resident are diplomatic ministers, which

are not the same thing as government ministers or

religious ministers. A diplomatic mission headed

by either type of Minister would be called a

Legation. As they formally represent the head of

state, they are entitled to use the title "His/Her

Excellency", which originally was reserved for

Ambassadors.

4. Chargé d'affaires ad interim, or simply

Chargé. As the French title suggests, a

chargé d'affaires would be in charge of an

embassy's or a legation's affairs in the

(usually temporary) absence of a more

senior diplomat.

As it turned out, this system of diplomatic rank did

nothing to solve the problem of the nations'

precedence. The appropriate diplomatic ranks

used would be determined by the precedence

among the nations; thus the exchanges of

ambassadors (the highest diplomatic rank) would

be reserved among major nations, or close allies

and related monarchies. In contrast, a major nation

would probably send just an envoy to a minor

nation, who in return would send an envoy to the

major nation. As a result, the United States did not

use the rank of ambassador until their emergence

as a major world power at the end of the 19th

Century. Indeed, until the mid-20th Century, the

majority of diplomats in the world were of the rank

of envoy.

In diplomatic parlance, all the diplomats that are assigned to

a nation are known collectively as the diplomatic corps; one

of these diplomats is recognized as the primus inter pares - in

practice rather a protocolar honor - who acts as the

spokesperson for all, known as the dean of the diplomatic

corps (generally based on the date of arrival in country or

presentation of credentials to the head of state, although in

some Catholic nations it is held automatically by the Papal

Nuncio).

After World War II, most legations were upgraded to

embassies, and the use of the rank of Minister for diplomatic

missions' highest-ranking officials gradually ceased. The last

U.S. Legation, in Sofia, Bulgaria, was upgraded to an

Embassy on November 28, 1966. Where those ranks still

exist, their incumbents usually act as embassy section chiefs

or Deputy Chief of Mission (deputy to the Ambassador

Modern diplomats

[edit]

Bilateral diplomacy

In modern diplomatic practice there are a number of diplomatic ranks

below Ambassador. Since most missions are now headed by an

Ambassador, these ranks now rarely indicate a mission's (or its host

nation's) relative importance, but rather reflect the diplomat's individual

seniority within their own nation's diplomatic career path and in the

diplomatic corps in the host nation:

Ambassador

Minister

Minister-Counselor

Counselor

First Secretary

Second Secretary

Third Secretary

Attaché

Assistant Attaché

In the United States Foreign Service, a system of personal ranks is

applied which roughly corresponds to these diplomatic ranks. Personal

ranks are differentiated as "Senior Foreign Service" (SFS) or "Foreign

Service Officer" (FSO). The SFS ranks, in descending order, are

Career Ambassador, awarded to career diplomats with extensive and

distinguished service; Career Minister, the highest regular senior rank;

Minister-Counselor; and Counselor. In U.S. terms, these correspond to

4-, 3-, 2- and 1-star General and Flag officers in the military,

respectively. Officers at these ranks may serve as Ambassadors and

the most senior positions in diplomatic missions. FSO ranks descend

from FS-1, equivalent to a full Colonel in the military, to FS-9, the

lowest rank in the U.S. Foreign Service personnel system. (Most FSOs

begin at the FS-5 or FS-6 level.) Personal rank is distinct from and

should not be confused with the diplomatic or consular rank assigned

at the time of appointment to a particular diplomatic or consular

mission. In a large mission, several Senior Foreign Service Officers

may serve under the Ambassador as Minister-Counselors, Counselors,

First Secretaries, and Attaches; in a small mission, an FS-2 may serve

as the lone Minister-Counselor of Embassy.

Multilateral diplomacy

Furthermore, outside this traditional pattern of bilateral diplomacy, as a

rule on a permanent residency basis (though sometimes doubling

elsewhere), certain ranks and positions were created specifically for

multilateral diplomacy:

A permanent representative is the equivalent of an ambassador,

normally of that rank, but accredited to an international body (mainly by

member - and possibly observer states), not to a head of state.

A resident representative (or sometimes simply representative) is the

equivalent - in rank and privileges - of an ambassador, but accredited

by an international organization (generally a United Nations Agency, or

a Bretton Woods Institution) to a country's government. The resident

representative typically heads the country office of that international

organization within that country.

A special ambassador is a government's specialist diplomat in a

particular field, not posted in residence, but often traveling around the

globe.

The U.S. Trade Representative is a diplomat of cabinet rank, in charge

of U.S. delegations in multilateral trade negotiations (since 1962).

The UN Secretary General personally mandates Special Envoys for a

particular field, e.g. Africa's long-term AIDS-problem, or ad hoc as for a

(civil) war zone; states, especially (regional) superpowers, may do the

same, e.g.:

– To help with the Northern Ireland peace process, the United States has

appointed a Special Envoy to Northern Ireland with the diplomatic rank of

Ambassador. As of 2006, the position was occupied by Mitchell Reiss.

– During the 2006 democracy movement in Nepal, India sent Karan Singh,

who is related to royalty in both predominantly Hindu countries, as Special

Envoy to neighbouring Nepal.

– In 2005, Belgium created a former cabinet member, Pierre Chevalier

Special Envoy of the OSCE presidency - in fact ahead of its 2006 turn as

rotatory Chairman-in-Office of the organisation - to mediate in the Gazprom

natural gas-pipeline crisis involving Russia, Ukraine and the EU.

The EU appoints various Special Representatives (some regional,

some thematic); e.g. in 2005 - as a response to events in Kyrgyzstan

and Uzbekistan - the Council of the EU appointed Jan Kubis as its

"Special Representative for Central Asia".

A case sui generis is the High Representative for Bosnia and

Herzegovina

Consular counterpart

Formally the consular career (ranking in descending order:

Consul-General, Consul, Vice-Consul, Consular Agent;

equivalents without any type of immunity include Honorary

Consul General, Honorary Consul, and Honorary Vice

Consul) forms a different hierarchy. (Other titles, including

"Vice Consul-General", have existed in the past.) Consular

titles may be used concurrently with diplomatic titles if the

individual is assigned to the embassy. At a separate

consular post, the official will have only a consular title.

Consular officers render a wide range of services to private

citizens, enterprises, et cetera. They can be more

numerous since diplomatic missions are posted only in a

nation's capital, while consular officials are stationed in

various other cities as well. However, it is not uncommon

for individuals to be transferred from one hierarchy to the

other, and for consular officials to serve in a capital

carrying out strictly consular duties

Basic setting and overview

The board is a map of Europe showing political boundaries as they existed at the beginning of the

20th century, divided into fifty-six land regions and nineteen sea regions.

Each player other than Russia begins the game with three units (armies and fleets); Russia has

four units (two armies and two fleets) to compensate for its larger area and number of neighbours.

Only one unit at a time may occupy a given map region. Thirty-four of the land regions contain

supply centers, corresponding to major centers of industry or commerce (e.g., "London," "Rome,").

The number of supply centers a player controls determines the total number of armies and fleets a

player may have on the board, and as players gain and lose control of different centers, they may

build and remove units accordingly. At the beginning of the game, there are twelve "neutral"

(unoccupied) supply centers; these are all typically captured within the first few moves, allowing all

the powers to ramp up their military strength. Thereafter the game becomes zero sum, with any

gains in a player's strength coming at the expense of a rival.

Players who control no supply centers are eliminated from the game, and victory is achieved if a

player controls eighteen of the thirty-four supply centers.

For the most part, the regions on the board are named after the general regions (e.g. "Bohemia") or

countries (e.g. "Finland"); however, home supply centers (i.e. supply centers that are occupied at

the beginning of the game) are named after the relevant cities (e.g. "Rome," "Vienna"). The

exception is that of "Tunis," which despite not being a home supply center is still named after a city.

If the convention was correctly followed, it would be labelled "Tunisia", and indeed is on some

variant maps. The original style is nonetheless an accurate recreation of early 20th century

European diplomatic language, as "Tunis" was then inclusive of both the city and its adjacent

hinterland.

The standard board also errs in referring to the United Kingdom as England. This too, however, is

in accord with the prevailing diplomatic practices of the early 20th century. The European diplomats

of the time often used "England" interchangeably with "Great Britain," "Britain," or "the United

Kingdom."

Further, Albania only existed as an independent entity from 1912 (during the First Balkan War)

onwards. In 1901 (the traditional first year of the game), the country was still part of the Ottoman

Empire - referred to as Turkey.

Game play

Diplomacy is turn-based - movement turns,

alternately designated "Spring" and "Fall"

moves, by convention begin in the year

1901. Prior to each movement phase,

there is a negotiation period in which

players entice, wheedle, bluff, cajole, and

threaten each other in an attempt to form

favorable partnerships. Secret negotiations

and secret agreements are explicitly

allowed, but no agreements of any kind are

enforceable.

After the negotiation period is over, players secretly write

orders for each unit and these orders are revealed

simultaneously and simultaneously executed. Choice of

orders include "move" (to any space adjacent to the unit's

current location), "support" (assist the move of a different

unit moving into a space adjacent to the unit's current

location), or "hold" (do nothing). Armies may only occupy

land regions, and fleets may only occupy sea regions and

land regions which border the sea. Fleets and armies in

combination can execute the move "convoy," which allows

transport of an army across either one (or multiple) bodies

of water to a distant land square. One Fleet per sea space

traversed is required if multiple bodies of water are to be

traversed.

Since only one unit can occupy any particular

game space, conflicts (such as two armies

ordered to enter the same space), are resolved

according to rules determining how much

"support" a unit has for its movement. When two

units attempt to occupy the same region, the one

with more support wins. The greatest

concentration of force is always victorious; if the

forces are equal a standoff results and the units

remain in their original positions. If a supporting

unit is attacked (except by the unit against which

the support is directed), the support is nullified,

which allows units to affect the outcome of

conflicts in regions not directly adjacent.

Occasionally these conceptually simple rules

result in situations which are

difficult to adjudicate, or even paradoxical.

Therefore the official rules contain comprehensive

details and examples. Also, one person may be

designated as Game Master to execute moves

and adjudicate disputes.

After each Fall move, occupied supply centers

become owned by the occupying player, and each

power's supply center total is recalculated. At that

point players with fewer supply centers than units

on the board must disband units, while players

with more supply centers than units on the board

are entitled to build units. Units may only be built

in that player's "Home" centers, that is, those

centers with which each Great Power begins the

game. Therefore, a player may not build units in

any captured "neutral" center or in another player's

"Home" centers.

The boundaries on the Diplomacy map are those

The Great Powers

Britain: A powerful sea nation with two fleets to start with, Britain can easily commit

itself to a war with either Russia, France or Germany. Its isolation means that it cannot

expect reprisals immediately, but needs to be careful not to take on more than it can

properly handle.

Germany: Sandwiched between Russia, Austria-Hungary and France, Germany is a

difficult nation to play. It must therefore often commit to alliances, like for example with

Austria-Hungary; this is good for both parties because it means they both have one

fewer enemy.

France: A very promising nation with Iberia to the west, France can often find itself in

an alliance with England or Germany or face an alliance from the two.

Italy: Considered by many Diplomacy players to be the most difficult nation on the

board, Italy is faced with a very troubling situation. France to the west and Austria-

Hungary to the east mean that after Tunisia, Italy must attack another nation to grow.

Austria-Hungary: Another very difficult nation to play, Austria-Hungary has more

neighbors than any other player (except Russia) and with only one fleet-building home

supply center, often finds itself forced to be a land power. They often get drawn into a

conflict in the Balkans (home of four neutral supply centers) and then find themselves

with no friends.

Russia: A very exciting nation to play, Russia is larger than any other nation and

although they have four neighbors, they begin the game with an extra unit. Because of

the large land area and several fronts, the possibilities for Russia are endless, leaving

a good Diplomacy player with several options.

Turkey: Much like England, the Turks find themselves in a corner of the board and

have few options in the beginning. Like England, they are likely safe from a home

invasion, but in order to invade, Turkish armies and fleets must travel far from home.

Strategy

Because numerical superiority is crucial to success, alliances are vital in Diplomacy. Each country is initially

roughly equal in strength, so it is very difficult to gain territory except by attacking with the support of a neighbor.

The excitement of the game is less in the tactics than in negotiation, coalition-building, and intrigue. Each player's

social and interpersonal skills are at least as important to the game as the player's strategic abilities.

Diplomacy commands a respect among aficionados of multiplayer games similar to the respect accorded to chess

among two-player games. Most multiplayer games can't help but involve coalition-building to some degree, but

only in Diplomacy is the negotiation so critical and so multi-faceted. The game can't be won by going it alone,

except in a last mad dash of aggression from a strong position. In the mean time one makes compromises and

promises to one's allies while spreading fear and misinformation among one's enemies. And the attacking of one's

allies (or the "stab") has a central role in the culture of Diplomacy. A stab can be crucial to victory, but may have

negative repercussions in interpersonal relations.

All of the countries on the map have a real chance for success if played properly. Each power requires a different

style of play. Italy and Austria-Hungary are often thought to be the weakest countries—Austria-Hungary because it

has many neighbors and can be eliminated early, Italy because it has a hard time expanding. However, if they

survive and prosper through the starting phase of the game, their central position can be a great advantage.

England and Turkey are generally considered to be the easiest to defend. Under Calhamer scoring (where an

outright victory is worth one point and participants in a draw split the point equally) Russia and France typically

score the most points, Italy and Austria-Hungary the fewest.

There is a natural buffer of spaces without supply centers between the western and eastern halves of the board.

Therefore the first few turns of a game usually break down into fighting amongst the western powers (England,

France, Germany) and eastern powers (Russia, Austria-Hungary, Turkey) for dominance in their areas followed by

a break out based on the results. Italy is a wild card with a relatively weak position, though if it commits to an

alliance in either of the two threesomes, the alliance can be pivotal.

In some circles cheating is not only allowed, but also actively encouraged. Players are allowed and expected to

move pieces between turns, add extra armies (the so-called "Flying Dutchmen"), listen in to private conversations,

change other players' written move orders and just about anything else they can get away with. In tournament

play, however, these forms of cheating are generally prohibited, leaving only the lying and backstabbing which is

prevalent wherever Diplomacy is played.

A diplomatic mission is a group of people from

one state or an international inter-governmental

organization (such as the United Nations)

present in another state to represent the sending

state/organization in the receiving state. In

practice, a diplomatic mission usually denotes

the permanent mission, namely the office of a

country's diplomatic representatives in the

capital city of another country.

Naming

A permanent diplomatic mission is usually

known as an embassy, and the head of

the mission is known as an ambassador.

Missions between Commonwealth

countries are known as High

Commissions and their heads are High

Commissioners. All missions to the United

Nations are known simply as Permanent

Missions, and the head of such a mission

is typically both a Permanent

Representative and an ambassador.

Some countries have more particular naming for their missions and staff: a Vatican

mission (the oldest continuous diplomacy in the world) is headed by a Nuncio and

consequently known as an Apostolic Nunciature, while Libya's missions were for a

long time known as People's Bureaus and the head of the mission was a Secretary.

(Libya has since switched back to standard nomenclature.)

In the past a diplomatic mission headed by a lower ranking official (an envoy or

minister resident) was known as a legation. Since the ranks of envoy and minister

resident are effectively obsolete, the designation of legation is no longer used today.

(See diplomatic rank.)

In cases of dispute, it is not uncommon for a country to recall its head of mission as a

sign of its displeasure. This is less drastic than cutting diplomatic relations completely,

and the mission will still continue operating more or less normally, but it will now be

headed by a chargé d'affaires who may have limited powers. Note that for the period

of succession between two heads of missions, a chargé d'affaires ad interim may be

appointed as caretaker; this does not imply any hostility to the host country.

A Consulate is similar to (but not the same as) a diplomatic office, but with focus on

dealing with individual persons and businesses, as defined by the Vienna Convention

on Consular Relations. A Consulate is generally a representative of the Embassy in

locales outside of the capital city. For instance, The British Embassy to the United

States is in Washington, D.C., and there are British Consulates in Los Angeles, New

York City, Houston, and so on.

The term "embassy" is often used to refer to the building or compound housing an

ambassador's offices and staff. Technically, "embassy" refers to the diplomatic

delegation itself, while the office building in which they work is known as a chancery,

but this distinction is rarely used in practice. Ambassadors reside in ambassadorial

residences, which enjoy the same rights as missions.

Gunboat diplomacy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

In international politics, gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of

conspicuous displays of military power—implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare, should terms not be

agreeable to the superior force.

Contents

[hide]

1 Origin of the term

2 Modern contexts

3 Examples

– 3.1 19th century

4 External links

[edit]

Origin of the term

The term comes from the age of warring European empires, where such displays typically involved demonstrations

of naval might—gunboats were a prominent type of warship and symbolized an advanced military. A country

negotiating with a European power—usually over issues of trade—would notice that a warship or fleet of ships had

appeared off its coast. The mere sight of such power almost always had a considerable effect, and it was rarely

necessary for such boats to use other measures, such as demonstrations of cannon fire.

A notable and controversial example of gunboat diplomacy was the Don Pacifico Incident in 1850, in which the

British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston dispatched a squadron of the Royal Navy to blockade the Greek port of

Piraeus in retaliation for the harming of a British subject, David Pacifico, in Athens, and the subsequent failure of

the government of King Otto to remunerate the Gibraltar-born (and therefore British) Pacifico.

The effectiveness of such simple demonstrations of an imperial nation's projection of force capabilities meant that

those nations with naval power, especially Britain, could establish military bases (for example, Diego Garcia) and

arrange economically advantageous relationships around the world. Aside from military conquest, gunboat

diplomacy was the dominant way to establish new trade partners, colonial outposts and expansion of empire.

Those lacking the resources and technological advancements of European empires found that their own peaceable

relationships were readily dismantled in the face of such pressures, and they therefore came to depend on the

imperial nations for access to raw materials and overseas markets. For up-and-coming industrial nations in the later

19th century, such as Germany and Japan, the rules of the game were

Modern contexts

Gunboat diplomacy is considered a form of hegemony. As the

United States became a military power in the first decade of the 20th

century, the Rooseveltian version of gunboat diplomacy, big stick

diplomacy, was partially superseded by dollar diplomacy: replacing

the big stick with the "juicy carrot" of American private investment.

However, during Woodrow Wilson's presidency, conventional

gunboat diplomacy did occur, most notably in the case of the U. S.

Army's occupation of Veracruz during Mexico's civil war.

Gunboat diplomacy in the post-Cold War world was still based on

naval forces. U. S. administrations have frequently changed the

disposition of their major naval fleets to influence opinion in foreign

capitals. More urgent diplomatic points were made by the Clinton

administration in the Balkans (in alliance with the United Kingdom's

Blair government) and elsewhere, using sea-launched Tomahawk

missiles. The term "gunboat diplomacy" has been superseded in

many circles by "power projection".

Protocol (diplomacy)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

– For other uses, see Protocol.

In international politics, protocol is the etiquette of diplomacy and

affairs of state.

A protocol is a rule which guides how an activity should be performed,

especially in the field of diplomacy. In the diplomatic and government

fields of endeavor protocols are often unwritten guidelines. Protocols

specify the proper and generally-accepted behavior in matters of state

and diplomacy, such as showing appropriate respect to a head of state,

ranking diplomats in chronological order of their accreditation at court,

and so on.

Public diplomacy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

In international relations, the term public diplomacy is a term coined in the 1960s to describe

aspects of international diplomacy other than the interactions between national governments. It

has been closely associated with the United States Information Agency, which used the term to

define its mission. It was originally a euphemism for purportedly truthful propaganda.

Standard diplomacy might be described as the ways in which government leaders communicate

with each other at the highest levels, the elite diplomacy we are all familiar with. Public

diplomacy, by contrast - according to the definition at the USC Center on Public Diplomacy -

focuses on the ways in which a country (or multi-lateral organization such as the United Nations)

communicates with citizens in other societies. A country may be acting deliberately or

inadvertently, and through both official and private individuals and institutions. Effective public

diplomacy starts from the premise that dialogue, rather than a sales pitch, is often central to

achieving the goals of foreign policy: public diplomacy must be seen as a two-way street.

Film, television, music, sports, video games and other social/cultural activities are seen by public

diplomacy advocates as enormously important avenues for otherwise diverse citizens to

understand each other and integral to the international cultural understanding, which they state is

a key goal of modern public diplomacy strategy. It involves not only shaping the message(s) that

a country wishes to present abroad, but also analyzing and understanding the ways that the

message is interpreted by diverse societies and developing the tools of listening and

conversation as well as the tools of persuasion.

One of the most successful initiatives which embodies the principles of effective public diplomacy

is the creation by international treaty in the 1950s of the European Coal and Steel Community

which later became the European Union. Its original purpose after World War II was to tie the

economies of Europe together so much that war would be impossible. Supporters of European

integration see it as having achieved both this goal and the extra benefit of catalysing greater

international understanding as European countries did more business together and the ties

among member states' citizens increased. Opponents of European integration are leery of a loss

of national sovereignty and greater centralization of power.

Shuttle diplomacy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

In diplomacy and international relations, shuttle diplomacy is the

use of a third party to serve as an intermediary or mediator between

two parties who do not talk directly. The third party travels frequently

back and forth (that is, "shuttles") between the two primary parties.

Shuttle diplomacy is often used when the two primary parties do not

formally recognize each other but still want to negotiate.

The term shuttle diplomacy became widespread following Henry

Kissinger's term as United States Secretary of State. Kissinger

participated in shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East and in the

People's Republic of China.

This politics-related article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by

expanding it.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shuttle_diplomacy

Track II diplomacy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

Track II diplomacy is a specific kind of informal diplomacy, in which non-officials

(academic scholars, retired civil and military officials, public figures, and social

activists) engage in dialogue, with the aim of conflict resolution, or confidence-

building.[1] This sort of diplomacy is especially useful after events which can be

interpreted in a number of different ways, both parties recognize this fact, and neither

side wants to escalate or involve third parties for fear of the situation spiraling out of

control. For example, a Chinese general recently commented that atomic bombs are

not out of the question if the PRC and the United States should engage in low-level

conflict over the Taiwan question. If the US immediately responded with heavy press

coverage and speeches by major officials, the PRC would then be forced to take

either of two stances: (1) admission that the general was incorrect, which would

inflame the Chinese population and cause grassroots ire and anti-American feeling, or

(2) claim that the general was correct, which would be deterimental to world peace

and diplomatic relations. Instead, the US would engage in Track II diplomacy to try to

understand whether the initial threat was as serious as it seemed to be. Dialogue

would be deliberately invited in order to determine the stance of the PRC without

creating a confrontational atmosphere.

Although Track II diplomacy may seem less important than Track I (the work of actual

diplomats at their embassies), it is many times far more important. Indeed its informal

nature often reflects the fact that the issues in question are of deadly seriousness. In

the above situation, the United States would at least ask that the other side clearly

demonstrate their understanding that they were the ones to make the initial threat,

even if no apology was eventually deemed necessary by either side.

[edit]

External link

You might also like

- Glossary of Diplomatic TermsDocument13 pagesGlossary of Diplomatic TermsMariaNo ratings yet

- The Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. VIIIFrom EverandThe Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution, Vol. VIIINo ratings yet

- Diplomatic DictionaryDocument27 pagesDiplomatic DictionaryMilena KovačevićNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy: I. Different DefinitionsDocument4 pagesDiplomacy: I. Different DefinitionsAbdul AzizNo ratings yet

- What Is DiplomacyDocument10 pagesWhat Is DiplomacyMihai Deaconu100% (1)

- DiplomacyDocument9 pagesDiplomacyHarshit Singh67% (3)

- Amendment Urgency of Vienna Convention 1961 On Diplomatic Relation in Relation To The Receiving State ProtectionDocument102 pagesAmendment Urgency of Vienna Convention 1961 On Diplomatic Relation in Relation To The Receiving State ProtectionAlfian Listya Kurniawan100% (1)

- Diplomacy .1Document19 pagesDiplomacy .1Sadia SaeedNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy, Theory & PracticeDocument15 pagesDiplomacy, Theory & PracticeSamson EsuduNo ratings yet

- DiplomacyDocument8 pagesDiplomacyRonnald WanzusiNo ratings yet

- China Local Govt Report: PRC SystemDocument26 pagesChina Local Govt Report: PRC SystemEmmanuel S. CaliwanNo ratings yet

- A Dictionary of Diplomatic Terminology Currently in CirculationDocument4 pagesA Dictionary of Diplomatic Terminology Currently in Circulationconcerto_grossoNo ratings yet

- Essentials of International Relations Chapter SummaryDocument65 pagesEssentials of International Relations Chapter SummaryMukhtiar AliNo ratings yet

- Definition of Public DiplomacyDocument101 pagesDefinition of Public DiplomacyNeola PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy Analysis 2Document8 pagesForeign Policy Analysis 2Arya Filoza PermadiNo ratings yet

- Dss 819 ProjectDocument16 pagesDss 819 ProjectOjo Favour EbonyNo ratings yet

- Modes of DiplomacyDocument3 pagesModes of Diplomacymevy eka nurhalizahNo ratings yet

- Insight On Africa 2014 Nzomo 89 111Document23 pagesInsight On Africa 2014 Nzomo 89 111Faisal SulimanNo ratings yet

- UgandaDocument1 pageUgandaHartford CourantNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic History, Diplomacy & Diplomat Sayed Shah Guloon National University of Modern Languages Date: October16, 2018Document9 pagesDiplomatic History, Diplomacy & Diplomat Sayed Shah Guloon National University of Modern Languages Date: October16, 2018Sayed Shah GuloonNo ratings yet

- International RelationsDocument18 pagesInternational RelationsahtishamNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Immunities: 1 Kdr/Iit Kgp/Rgsoipl/-2008Document31 pagesDiplomatic Immunities: 1 Kdr/Iit Kgp/Rgsoipl/-2008Raju KDNo ratings yet

- ch01 PDFDocument32 pagesch01 PDFNoureddin BakirNo ratings yet

- The Arab League: A Regional Organization Promoting Arab InterestsDocument2 pagesThe Arab League: A Regional Organization Promoting Arab InterestsMarina DinuNo ratings yet

- The Actors of Foreign PolicyDocument3 pagesThe Actors of Foreign Policymarlou agustinNo ratings yet

- Islamic Republic of Iran: Profile GeographyDocument14 pagesIslamic Republic of Iran: Profile Geographypranay0923100% (1)

- Diplomatic Protocol ManualDocument9 pagesDiplomatic Protocol ManualDiana FurculitaNo ratings yet

- 1.1. Conceptualizing Nationalism, Nations and States: Chapter One Understanding International RelationsDocument21 pages1.1. Conceptualizing Nationalism, Nations and States: Chapter One Understanding International RelationsWiz SantaNo ratings yet

- Essay - Economic Diplomacy - The Case of China and ZambiaDocument8 pagesEssay - Economic Diplomacy - The Case of China and ZambiaMeha LodhaNo ratings yet

- Philippines national security perceptionsDocument4 pagesPhilippines national security perceptionsjealousmistressNo ratings yet

- Israel's Economy March 2011Document38 pagesIsrael's Economy March 2011Economic Mission, Embassy of IsraelNo ratings yet

- National Interest: Definition: 1. An Interest Which The States Seek To Protect or Achieve in Relation To Each OtherDocument15 pagesNational Interest: Definition: 1. An Interest Which The States Seek To Protect or Achieve in Relation To Each OtherTehneat ArshadNo ratings yet

- Indonesia, Cyber Security, DiplomacyDocument19 pagesIndonesia, Cyber Security, Diplomacyihsan nasihinNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between League of Nations and United NationsDocument2 pagesComparison Between League of Nations and United NationsSAI CHAITANYA YEPURINo ratings yet

- History and Structure of The United Nati PDFDocument69 pagesHistory and Structure of The United Nati PDFsatyam kumarNo ratings yet

- Global Trends - OneDocument30 pagesGlobal Trends - OneSebehadin Kedir100% (1)

- EDUTRAINIA Technical SpecificationDocument17 pagesEDUTRAINIA Technical SpecificationSaad0% (1)

- Diplomacy - Meaning, Nature, Functions and Role in Crisis Management PDFDocument12 pagesDiplomacy - Meaning, Nature, Functions and Role in Crisis Management PDFdarakhshan88% (8)

- Global AffairDocument70 pagesGlobal Affairbalemigebu2No ratings yet

- Understanding National Interest: Its Meaning, Components and Methods of SecuringDocument13 pagesUnderstanding National Interest: Its Meaning, Components and Methods of SecuringAyesha FarooqNo ratings yet

- (Cambridge Studies in International Relations) James N. Rosenau, Ernst-Otto Czempiel-Governance Without Government - Order and Change in World Politics-Cambridge University Press (1992) PDFDocument323 pages(Cambridge Studies in International Relations) James N. Rosenau, Ernst-Otto Czempiel-Governance Without Government - Order and Change in World Politics-Cambridge University Press (1992) PDFAndrada BochișNo ratings yet

- Perils of Muslim UnionDocument8 pagesPerils of Muslim UnionMir Ahmad FerozNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Etiquette and Protocol ExplainedDocument6 pagesDiplomatic Etiquette and Protocol ExplainedMwaniki MichelleNo ratings yet

- Dominican Passport - Well Within Your Reach: An Exclusive Report by Mr. D For SM-C ReadersDocument19 pagesDominican Passport - Well Within Your Reach: An Exclusive Report by Mr. D For SM-C ReadersSven LidénNo ratings yet

- AdictionaryofdiplomacyDocument313 pagesAdictionaryofdiplomacyZulNo ratings yet

- DiplomacyDocument26 pagesDiplomacyRiya GargNo ratings yet

- Geneva Convention of 1929Document40 pagesGeneva Convention of 1929ndd616No ratings yet

- The Youth Bulge in Egypt - An Intersection of Demographics SecurDocument18 pagesThe Youth Bulge in Egypt - An Intersection of Demographics Securnoelje100% (1)

- Diplomatic HistoryDocument2 pagesDiplomatic HistoryBogdan Ursu0% (1)

- International OrganizationsDocument15 pagesInternational OrganizationsDahl Abella Talosig100% (1)

- The International Monetary SystemDocument2 pagesThe International Monetary SystemMohamed MadyNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic CorrespondenceDocument4 pagesDiplomatic Correspondenceromeo stod100% (1)

- Inviolability of Diplomatic ArchivesDocument13 pagesInviolability of Diplomatic ArchivesMichelle Anne VargasNo ratings yet

- Diplomats and Diplomatic MissionsDocument4 pagesDiplomats and Diplomatic Missionsthe angriest shinobiNo ratings yet

- 7th Lecture Batch 159Document66 pages7th Lecture Batch 159Tooba ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Terminology: Student Mukimov H. Teacher Safarova RDocument35 pagesDiplomatic Terminology: Student Mukimov H. Teacher Safarova RШарифзода Муҳабати МуродалиNo ratings yet

- The Role of The AmbassadorDocument1 pageThe Role of The AmbassadorAmbassador Timothy L. TowellNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Peace: Presented By: Ammarah Farhat AbbasDocument67 pagesApproaches To Peace: Presented By: Ammarah Farhat AbbasMuhammad HussainNo ratings yet

- Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations ExplainedDocument3 pagesVienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations ExplainedIon VerejanuNo ratings yet

- POLS 1 Sec. 80Document7 pagesPOLS 1 Sec. 80Jeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- What Is Leadership?Document36 pagesWhat Is Leadership?oxfordentrepreneur89% (9)

- ACES Tracer Study Provides Insights on GraduatesDocument2 pagesACES Tracer Study Provides Insights on GraduatesJes Ramos100% (1)

- Different Leadership Styles and The Effectiveness of These.Document27 pagesDifferent Leadership Styles and The Effectiveness of These.Dr Tahir javed100% (8)

- PDF Module10 Public Fiscal Administration DLDocument9 pagesPDF Module10 Public Fiscal Administration DLJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- A1061 Field TripsDocument22 pagesA1061 Field TripsJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Excellence in Strategic Planning Master Temp Strategic PlanDocument32 pagesExcellence in Strategic Planning Master Temp Strategic Planearl58No ratings yet

- 2015 Retail PricelistDocument8 pages2015 Retail PricelistclubdetiroalblancovaldiviaNo ratings yet

- A Little Too Not Over YouDocument2 pagesA Little Too Not Over YouJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Authorization UMAK Rafael PDFDocument3 pagesAuthorization UMAK Rafael PDFJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Politicsand Governmentsof Latin America Spring 2015Document15 pagesPoliticsand Governmentsof Latin America Spring 2015Jeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Authorization UMAK RafaelDocument3 pagesAuthorization UMAK RafaelJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- AtfDocument4 pagesAtfJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- SCTP Nssa-Nsca Membership Application: Please Fill inDocument1 pageSCTP Nssa-Nsca Membership Application: Please Fill inJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- PS582 Quantitative Analysis II Fall 2011 SyllabusDocument3 pagesPS582 Quantitative Analysis II Fall 2011 SyllabusJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- A Module in Preparing An Online Instruction Delivery Plan PDFDocument21 pagesA Module in Preparing An Online Instruction Delivery Plan PDFJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Gamefowl Medication GuideDocument2 pagesGamefowl Medication Guidechristine goalsNo ratings yet

- Hague-Harrop-comparative-government-and-politics - An-Introduction-2001 - Ch. 5Document18 pagesHague-Harrop-comparative-government-and-politics - An-Introduction-2001 - Ch. 5Jeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- 11 Book ReviewDocument19 pages11 Book ReviewGabriela Silang67% (3)

- Politics Modules: Department of Politics Birkbeck, University of LondonDocument47 pagesPolitics Modules: Department of Politics Birkbeck, University of LondonJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- PS 552: Quantitative Analysis of Political Data Spring 2009: Math CampDocument5 pagesPS 552: Quantitative Analysis of Political Data Spring 2009: Math CampJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Candidacy: Last Name First Name Middle Name Present Address College Department Gender Age Contact NumberDocument1 pageCertificate of Candidacy: Last Name First Name Middle Name Present Address College Department Gender Age Contact NumberJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Google Classroom Cheat Sheet For Teachers by Shake Up LearningDocument40 pagesGoogle Classroom Cheat Sheet For Teachers by Shake Up Learningapi-249144920100% (3)

- Republic of The Philippines Legal Education Board: Quezon CityDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Legal Education Board: Quezon CityAl M. GamzNo ratings yet

- IGAOHRA For The Period of State of Public Calamity Final Version 6 July3Document7 pagesIGAOHRA For The Period of State of Public Calamity Final Version 6 July3Jeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- BJ20 Brochure PDFDocument2 pagesBJ20 Brochure PDFJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Hague-Harrop-comparative-government-and-politics - An-Introduction-2001 - Ch. 5Document18 pagesHague-Harrop-comparative-government-and-politics - An-Introduction-2001 - Ch. 5Jeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Nathaniel Lepasana's Outstanding LoansDocument1 pageNathaniel Lepasana's Outstanding LoansJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Political Science 2053 Introduction To Comparative Politics Course SyllabusDocument5 pagesPolitical Science 2053 Introduction To Comparative Politics Course SyllabusJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Teachers Guide To Google Classroom PDFDocument46 pagesTeachers Guide To Google Classroom PDFpotter macNo ratings yet

- All Things Zombie - Better Dead Than ZedDocument92 pagesAll Things Zombie - Better Dead Than ZedNick Pluto100% (8)

- Peerless Devil Lord Sister Morning MishapDocument266 pagesPeerless Devil Lord Sister Morning MishapEihYah100% (4)

- Hóa Đơn Grab Tháng 9Document2 pagesHóa Đơn Grab Tháng 9Rin ChanNo ratings yet

- DBQ On Treaty of VersaillesDocument4 pagesDBQ On Treaty of Versaillesapi-421605069No ratings yet

- Cry of Pugad Lawin ControversyDocument2 pagesCry of Pugad Lawin ControversyAru Vhin100% (1)

- Regles DitTDocument29 pagesRegles DitTAnthony Tadd CrebsNo ratings yet

- Pro:Anti Imperialism DocumentsDocument3 pagesPro:Anti Imperialism DocumentsKade McAllisterNo ratings yet

- 2017 CAMM Data SheetDocument2 pages2017 CAMM Data SheetFanamar MarNo ratings yet

- Hitler in ZurichDocument5 pagesHitler in ZurichPriska WeberNo ratings yet

- CIA Feb 06 RETAIL-webDocument24 pagesCIA Feb 06 RETAIL-webJohn KubenaNo ratings yet

- AFV Ukraine/Russia War 2022Document173 pagesAFV Ukraine/Russia War 2022Bogdan Kozlov100% (1)

- Scenario For NORAD Training Exercise With Suicide Pilot in June 2001Document3 pagesScenario For NORAD Training Exercise With Suicide Pilot in June 20019/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Unification of JapanDocument4 pagesThe Rise of Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Unification of JapanfruittinglesNo ratings yet

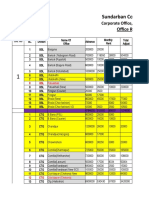

- Sundarban Courier Service PVT - LTD.: Office Rent AgreementDocument24 pagesSundarban Courier Service PVT - LTD.: Office Rent AgreementsajedulNo ratings yet

- Imperium ArbiterDocument190 pagesImperium ArbiterRebecca NietoNo ratings yet

- Aid and Comfort To The Enemy - American Legion Honchos Betray Liberty Veterans - Uss Liberty-26Document26 pagesAid and Comfort To The Enemy - American Legion Honchos Betray Liberty Veterans - Uss Liberty-26Keith KnightNo ratings yet

- Public International Law SyllabusDocument7 pagesPublic International Law SyllabusMichael Kevin MangaoNo ratings yet

- Vietnam War RevisitedDocument3 pagesVietnam War RevisitedPatricia SusckindNo ratings yet

- 884 ConversionDocument111 pages884 ConversionMd Abed Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- GFF - Eternal Dynasty 3.1.0Document3 pagesGFF - Eternal Dynasty 3.1.0afwsefwefvNo ratings yet

- Wh40k - DeathWatch - Codex 7E 22Document4 pagesWh40k - DeathWatch - Codex 7E 22dumbbeauNo ratings yet

- Rotterdam - WikipediaDocument206 pagesRotterdam - WikipediaYuvaraj BhaduryNo ratings yet

- Abraham Lincoln's Fight for EqualityDocument3 pagesAbraham Lincoln's Fight for EqualityAthaya ZanettaNo ratings yet

- Why Americans Misunderstand - CDocument226 pagesWhy Americans Misunderstand - CavertebrateNo ratings yet

- Ceylon and the Portuguese: 1505-1658Document324 pagesCeylon and the Portuguese: 1505-1658cecbNo ratings yet

- Ar 840-10Document82 pagesAr 840-10mcmanueljrNo ratings yet

- Avalon Hill Cross of Iron Scenario 4Document1 pageAvalon Hill Cross of Iron Scenario 4GianfrancoNo ratings yet

- GADocument233 pagesGAsaumitra2No ratings yet

- Russian Revolution Flowchart Part 1Document2 pagesRussian Revolution Flowchart Part 1api-278204574No ratings yet