Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Post-Natal Development of Human Brain Related To Motor

Uploaded by

aulia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views35 pagesOriginal Title

Post-Natal Development of Human Brain related to Motor

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views35 pagesPost-Natal Development of Human Brain Related To Motor

Uploaded by

auliaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 35

Post-Natal Development of

Human Brain related to Motor,

Sensory, and Higher Function

TUTOR 4

Nadhirah Siti Lutfiyah

Brain Development

• Neurogenesis

• Wiring The Brain : Growth and Guidance of Axon

and Dendrites

• Formation and Strengthening of Synapes

• Laying the Insulation : Glia and Myelination

• Neural Plasticity : The ability of the brain to

reorganize in response to its environment

Early Brain Development

• In the months after birth the brain grows rapidly, producing

billions of neurons, dendrites and axons, as well as synapses

reaching its peak around the infant’s first birthday.

-In the first 2 years the brain increases in size from 25% to 75% of its adult

weight

• Soon after synapses soon to gradually disappear a phenomenon

known as synaptic pruning.

-This process is the brain’s way of “weeding out” the unnecessary

connections between neurons.

Brain growth and development

• There is a fivefold increase in the number of dendrites in

cortex from birth to age 2 years, as a result approximately

15,000 new connections may be established per neuron.

• This is called “Transient exuberance”

• These connections are necessary because thinking and

learning require many connections between many parts of

the brain

• Experience is vital for brain formation

If cells are unused they atrophy and are

rededicated to other senses. Underused

neurons, like synapses are inactivated

by pruning process

When children suffer brain damage,

cognitive processes are usually impaired;

these processes often improve gradually

showing the brain’s plasticity

The brain’s organization is somewhat flexible and

if damaged the brain can make new connections

Motor Function Development

Motor development is the change in the motor behaviour experienced

over the life span. The process and the product of motor development

are related to age, and motor development’s study has roots in biology

and psycology.

• Gross Motor Skills: movements related to large muscles such as legs,

arms, etc.

• Fine Motor Skills: movements involving smaller muscle groups such

as those in the hand and wrist.

Gross Motor

Fine Motor

Sensory Function Development

• The sensory needs of a person change with time

• A child’s sensory processing will mature as they get older

• We all experience sensations in our own individual ways

• Some people can be extremely sensitive to noise, light, touch, smell

or movement

• Others may under-respond to such sensations

• So its all experience based

Higher Function Development

9 Key Executive Functions

• Awareness —Age-appropriate insight of strengths and weaknesses.

• Planning —Spontaneous use of planning behaviors in novel tasks;

anticipate future events; grasp main idea; prioritize, reduce/cluster

information, re-arrange material or information.

• Goal setting —Set intermediate and long-term goals appropriate to

abilities.

• Self-initiation —Independently initiate new activities; spontaneous in

conversation; begins activity without procrastination, seek and search

for information, generate ideas, persist, complete all parts of an

activity.

• Self-monitoring —Independently assess behaviors/ responses and make

changes as needed.

• Self-inhibiting —Behavior is appropriate to changing situations; control

impulses, think before acting, pace actions; follow or select according to

rules or criteria; manage extraneous distractions, irrelevant information or

interference; delay responses.

• Ability to change set —Demonstrate appropriate variations in behaviors;

independently consider a variety of solutions in problem solving; revise

plans, move freely from one step/activity/situation to another; transition

between tasks easily.

• Strategic behavior —Create useful strategies for functional use; able to

describe these.

• Working memory —Hold information in mind for the purpose of

completing a task.

• Executive functions develop across the life span with the first

signs noted in infancy. Research has shown inhibitory control

and working memory skills emerging in children as young as 7-

12 months. This is seen through means-end development. The

child is able to hold one piece of information in mind in order

to act on another. The skill is very fragile and highly susceptible

to distraction.

• By the age of one, children begin to display gains in selective

attention with external distraction not as predominate.

• At the age of two, children become more capable of problem solving

with the acquisition of language. They begin to use language to

regulate behavior. At two, children are also able to follow verbal rules,

requests and directives. They are beginning to keep verbal rules in

mind and use them to guide their behavior. Gains in rule and language

use continue to grow and impact learning.

• By three years of age, the child is no longer impulsively responding to

stimuli in a rigid stereotyped means but rather acting deliberately and

flexibly in light of a conscious plan.

• Between the ages of three and five, children demonstrate significant

gain in performance on tasks of inhibition and working memory. They

are beginning to reflect on their own actions. Cognitive flexibility,

goal-directed behavior and planning gains are noted. They are

developing complex sets of rules to guide/regulate their behavior.

They begin to ‘think’ about the intention or the act of doing rather

than simply responding to the environment.

• As children mature and change, they continue to gain in inhibitory

control, and attentional capabilities are noted. During the primary

school years and into early adolescence, the main changes are made

in the ability to consider variables and act accordingly. Preschoolers

can verbalize their knowledge of what is the right thing to do but

often are not able to actually follow through on it. The need for

immediate gratification overrides planning and reasoning capabilities.

Further, their ability to successfully implement strategies to limit

impulsive responses are not yet developed, though emerging.

• External supports and modeling provide reinforcement and

help internalize strategies. Gains in planning, goal setting/

directed behaviors problem solving and cognitive flexibility

are continuing and providing the basis for social skills and

academic success during pre-adolescence and adolescence.

• The role of executive function development is most clearly

demonstrated and often most acknowledged during the

teenage/ adolescent years. This is in part due to high-risk

behaviors that are observed during adolescence, such as

alcohol/drug use and unprotected sex.

• By the age of 15, working memory, inhibitory control and the ability

to sustain and appropriately shift attention are close to adult levels

and remain relatively stable with some small increases noted into

adulthood. Though, the teen is functioning at or near adult levels,

their self-monitoring and self-reflective abilities are not fully mature.

Further, when placed in highly complex situations or a situation in

which one is required to integrate numerous pieces of information to

make an informed decision, the teen will show shortcomings. They

tend to base decisions on the advantage of a given situation versus

the disadvantages.

• Decisions and actions are based on the specific moment and do not

consider the long-term consequences, rather making decisions based

on their view of themselves at the moment and how they will be

perceived by outsiders.

• Dr. Zelazo (2010) explains the shortcoming as a “competition between

the top-down influence of executive function and the bottom-up

influence of desires, drives, impulses and habits.”

• As the executive system matures, adults are able to use stored

knowledge about themselves and draw on their past experience in

making decisions.

• In adulthood, gains and decline in executive skills are noted. Between

the ages of 20-29, executive functioning skills are at their peak.

Decisions regarding marriage, career, family and long-term goals are

stable, reflective and highly obtainable. Consideration to outside

influences are weighed with internal drives to develop the best

outcomes.

• As the adult ages, executive functions once again change but this time

showing a decline. Declines in higher order cognitive skills have been

clearly noted in working memory, self-monitoring, and spatial skills.

What has been thought of as normal changes in aging may be the

result of an aging in the prefrontal cortex and demyelination—a

deterioration of the myelin sheath surrounding neurons which results

in a slowing of impulses that travel along the nerve.

• The adage of “use it or lose it” may very well be true in the realm of

executive skills. Continued cognitive involvement/ stimulation may

promote neuronal myelination or, at minimum, slow the course of

demyelination contributing to greater quality of life, independence

and overall functional skill.

References

• Nelson

• Swaimman

• https://www.rainbowrehab.com/executive-functioning/#attachment

%20wp-att-6197/0/

• https://childdevelopment.com.au/resources/child-development-chart

s

• Brain Development by Grey Matter

You might also like

- Principles of Growth and DevelopmentDocument106 pagesPrinciples of Growth and DevelopmentDheeraj Sikri57% (7)

- 10 Things I Would Do If I Were A CelebrityDocument3 pages10 Things I Would Do If I Were A CelebrityAnne Marian JosephNo ratings yet

- CBE 2021 Prof Ed 102Document65 pagesCBE 2021 Prof Ed 102Fai LanelNo ratings yet

- Human Growth and Development: Chapter 9Document41 pagesHuman Growth and Development: Chapter 9khaidhirNo ratings yet

- Development in Middle ChildhoodDocument42 pagesDevelopment in Middle ChildhoodArielle Kate Estabillo100% (1)

- Lifespan Approach to Human DevelopmentDocument14 pagesLifespan Approach to Human DevelopmentCeleste De VeraNo ratings yet

- Early Brain Development: Implications and Understandings When Assessing Cognitive Functioning and Brain InjuryDocument49 pagesEarly Brain Development: Implications and Understandings When Assessing Cognitive Functioning and Brain InjuryBelle ElliottNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Human DevelopmentDocument36 pagesLesson 1 Human DevelopmentalexanderNo ratings yet

- NMD-3 Motor Development Stages 27.09Document39 pagesNMD-3 Motor Development Stages 27.09Yorgos TheodosiadisNo ratings yet

- PED 6 Child and Adolescent Learner and Learning Principles Foundation of Special and Inclusive EducationDocument11 pagesPED 6 Child and Adolescent Learner and Learning Principles Foundation of Special and Inclusive EducationlorylainevalenzonatorresNo ratings yet

- Assessing Emotional and Behaviour Difficulties in Adolescents Psychological Intervention ReviewDocument27 pagesAssessing Emotional and Behaviour Difficulties in Adolescents Psychological Intervention ReviewNam JesusNo ratings yet

- Psychological Theories of CrimesDocument29 pagesPsychological Theories of CrimesAngelica Nicole Reyes MascariñasNo ratings yet

- Early Child Development and RisksDocument39 pagesEarly Child Development and RisksNamakau MuliloNo ratings yet

- 12 notes (LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT) (1)Document4 pages12 notes (LIFESPAN DEVELOPMENT) (1)xoranek474No ratings yet

- How educators and healthcare providers can help teens develop healthy brainsDocument13 pagesHow educators and healthcare providers can help teens develop healthy brainsWeng MalateNo ratings yet

- Early Identification and Screening: Definition of Developmental DelayDocument7 pagesEarly Identification and Screening: Definition of Developmental Delayadheena simonNo ratings yet

- Children LiteratureDocument11 pagesChildren LiteratureliliyayanonoNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Late ChildhoodDocument17 pagesGroup 4 Late ChildhoodCristan AlmazanNo ratings yet

- Human Growth Learning and Development PowerpointDocument366 pagesHuman Growth Learning and Development PowerpointKlaribelle Villaceran100% (10)

- Cognitive DevelopmentDocument58 pagesCognitive DevelopmentDaphnee PitaNo ratings yet

- Developmental Characteristics of Children and Adolescence SARAH&JAYBERTDocument7 pagesDevelopmental Characteristics of Children and Adolescence SARAH&JAYBERTjaybertNo ratings yet

- Middle Childhood: Physical and Cognitive DevelopmentDocument63 pagesMiddle Childhood: Physical and Cognitive DevelopmentNozima ToirovaNo ratings yet

- Module 31 Prof Ed 1Document23 pagesModule 31 Prof Ed 1Carl Velacruz OnrubsNo ratings yet

- Prof (DR.) Nasrin: Learning Religious and Moral Values For Early Childhood Using A Neuroscience ApproachDocument34 pagesProf (DR.) Nasrin: Learning Religious and Moral Values For Early Childhood Using A Neuroscience ApproachQurroti Jurnal piaudNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Middle ChildhoodDocument29 pagesUnit 4 Middle ChildhoodMarybell AycoNo ratings yet

- Session 4: The Changing MindsDocument21 pagesSession 4: The Changing MindsJay-RNo ratings yet

- 07: Cognitive Development and The Teenage Years: Student ObjectivesDocument10 pages07: Cognitive Development and The Teenage Years: Student ObjectivesŞterbeţ RuxandraNo ratings yet

- S1 Principles of Child DevelopmentDocument40 pagesS1 Principles of Child Developmentbevelyn caramoanNo ratings yet

- Physical Development in Middle ChildhoodDocument29 pagesPhysical Development in Middle Childhoodpronzipe14No ratings yet

- Physical and Cognitive Development in ChildhoodDocument23 pagesPhysical and Cognitive Development in Childhoodgraham jarvis-lingardNo ratings yet

- 171 Chapter 7Document6 pages171 Chapter 7Rashia LubuguinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1.2 Periods and Developmental TasksDocument49 pagesChapter 1.2 Periods and Developmental Tasksshielaoliveros73020No ratings yet

- Growth and DevelopmentDocument150 pagesGrowth and Developmentvicson_4No ratings yet

- 6 # School Child & AdolescenceDocument32 pages6 # School Child & AdolescenceShahbaz aliNo ratings yet

- Sle Cad Module 25Document4 pagesSle Cad Module 25Kimberlie Daco TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive DevelopmentDocument32 pagesCognitive Developmentapi-327646994No ratings yet

- Life Span DevelopmentDocument48 pagesLife Span DevelopmentAadrika JoshiNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent LearnersDocument11 pagesChild and Adolescent LearnersAbren ManaloNo ratings yet

- Cognitive and Moral Development TheoriesDocument5 pagesCognitive and Moral Development TheoriesFranz Louisse OcampoNo ratings yet

- Classifying of Children's Cooperative Behavior: Pedodontics Lec. 3Document8 pagesClassifying of Children's Cooperative Behavior: Pedodontics Lec. 3Haider F YehyaNo ratings yet

- Signs of Mental Retardation in ChildrenDocument6 pagesSigns of Mental Retardation in ChildrenShine 2009No ratings yet

- Aspects of Deve WPS OfficeDocument3 pagesAspects of Deve WPS OfficeDada MielNo ratings yet

- PSTM Lesson 2Document4 pagesPSTM Lesson 2Julius VillarealNo ratings yet

- General Principles of Human DevelopmentDocument41 pagesGeneral Principles of Human DevelopmentReiNo ratings yet

- Module 25 - Cognitive Development of High School LearnersDocument19 pagesModule 25 - Cognitive Development of High School LearnersArabelle PazNo ratings yet

- Psychology 1Document12 pagesPsychology 1leher shahNo ratings yet

- Human DevelopmentpptxDocument20 pagesHuman DevelopmentpptxRembe Belleno100% (1)

- Week 13 & 14 WorksheetsDocument5 pagesWeek 13 & 14 Worksheetsmae fuyonanNo ratings yet

- Learner-Centered Teaching PrinciplesDocument5 pagesLearner-Centered Teaching Principlescee padillaNo ratings yet

- 3 Stages of Human DevelopmentDocument57 pages3 Stages of Human DevelopmentKaren FalsisNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 25: Cognitive Development of The High School LearnersDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 25: Cognitive Development of The High School LearnersDarlyn BangsoyNo ratings yet

- Build on your strengths and work on your weaknessesDocument44 pagesBuild on your strengths and work on your weaknessesRaiza CabreraNo ratings yet

- PD1Document5 pagesPD1Czyrine krizheNo ratings yet

- Factors Determining Learning and DevelopmentDocument40 pagesFactors Determining Learning and DevelopmentchichiNo ratings yet

- Physical Development in Middle ChildhoodDocument26 pagesPhysical Development in Middle ChildhoodHuzaifah Bin SaeedNo ratings yet

- Advanced Developmental Psychology: Chapters 11-15 Lifespan 3 Ed. Broderick & BlewittDocument25 pagesAdvanced Developmental Psychology: Chapters 11-15 Lifespan 3 Ed. Broderick & BlewittGeorgia-Rae SalvatoreNo ratings yet

- Human Development Module from Cebu Technological UniversityDocument14 pagesHuman Development Module from Cebu Technological UniversityJewel SkyNo ratings yet

- Issues in Child DevelopmentDocument21 pagesIssues in Child DevelopmentCristel Jane SarigumbaNo ratings yet

- Putting Mind Control Tactics In Your Daily Life : Exploit This Technology To Get What You Want, And Be Protected Against Its Powers!From EverandPutting Mind Control Tactics In Your Daily Life : Exploit This Technology To Get What You Want, And Be Protected Against Its Powers!No ratings yet

- Daring to Dream: A Teen's Journey in Skills Acquisition and ExplorationFrom EverandDaring to Dream: A Teen's Journey in Skills Acquisition and ExplorationNo ratings yet

- DRAFT SOOCA CASE 1 RESPI: RHINOSINUSITISDocument12 pagesDRAFT SOOCA CASE 1 RESPI: RHINOSINUSITISauliaNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Upper Respiratory Tract: Guyton Ed 12 THDocument22 pagesPhysiology of Upper Respiratory Tract: Guyton Ed 12 THauliaNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Cycle and Heart Pump RegulationDocument15 pagesCardiac Cycle and Heart Pump RegulationauliaNo ratings yet

- Visual AcuityDocument9 pagesVisual AcuityauliaNo ratings yet

- Vector Borne TransmissionDocument5 pagesVector Borne TransmissionauliaNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Upper Respiratory Tract: Guyton Ed 12 THDocument22 pagesPhysiology of Upper Respiratory Tract: Guyton Ed 12 THauliaNo ratings yet

- Visual AcuityDocument9 pagesVisual AcuityauliaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological PropertiesDocument19 pagesPharmacological PropertiesauliaNo ratings yet

- Visual AcuityDocument9 pagesVisual AcuityauliaNo ratings yet

- Mechanism Blood Flow ControlDocument9 pagesMechanism Blood Flow ControlauliaNo ratings yet

- MOM GA Transport & QAQC CoordinationDocument2 pagesMOM GA Transport & QAQC CoordinationErik EstradaNo ratings yet

- PDF A Book Report On Farmacology by Daphne MillerDocument5 pagesPDF A Book Report On Farmacology by Daphne Millermario gemzonNo ratings yet

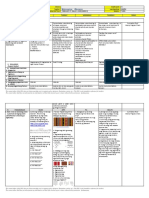

- MAPEH Daily Lesson LogDocument11 pagesMAPEH Daily Lesson LogMARTIN YUI LOPEZNo ratings yet

- Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs, 25e (May 8, 2023)_(0889376328)_(Hogrefe Publishing) ( Etc.) (Z-Library)Document555 pagesClinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs, 25e (May 8, 2023)_(0889376328)_(Hogrefe Publishing) ( Etc.) (Z-Library)Dragutin PetrićNo ratings yet

- Lab1 MEM14089A Cluster AT3A Student 191106Document12 pagesLab1 MEM14089A Cluster AT3A Student 191106Shan YasirNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Disordered Eating - 06 - Improving Low Self-EsteemDocument11 pagesOvercoming Disordered Eating - 06 - Improving Low Self-EsteemYesha ShahNo ratings yet

- How To Negotiate With Nursing Authority Figures (Rough)Document2 pagesHow To Negotiate With Nursing Authority Figures (Rough)Meet DandiwalNo ratings yet

- Hemodynamic Effects of Dexmedetomidine vs ClonidineDocument12 pagesHemodynamic Effects of Dexmedetomidine vs ClonidinezzzzNo ratings yet

- EDocument56 pagesEimee tan100% (3)

- HR Policies of Dell: Presented ByDocument12 pagesHR Policies of Dell: Presented ByMohit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Anil's GhostDocument2 pagesAnil's Ghostfaatema0% (1)

- Chapter 20 Tobacco: Lesson 2 Choosing To Live Tobacco FreeDocument2 pagesChapter 20 Tobacco: Lesson 2 Choosing To Live Tobacco Freeroshni rNo ratings yet

- Immuno GlowDocument11 pagesImmuno GlowNoly ClaveringNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human Subjectivity and IntersubjectivityDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Human Subjectivity and IntersubjectivityKimchiiNo ratings yet

- How To Dramatically Increase Your Vocal Range PDFDocument25 pagesHow To Dramatically Increase Your Vocal Range PDFjoaosilvaNo ratings yet

- IELTS READING TEST 33: Bilingualism Advantages and Changing Health RulesDocument12 pagesIELTS READING TEST 33: Bilingualism Advantages and Changing Health RulesDollar KhokharNo ratings yet

- 1023 3581 1 PBDocument4 pages1023 3581 1 PBfitriNo ratings yet

- Hope Week 2Document5 pagesHope Week 2Bea CabacunganNo ratings yet

- OSHA Complaint FinalDocument3 pagesOSHA Complaint FinalBethanyNo ratings yet

- Evidence Plan: Prepare/Stake Out Building LinesDocument2 pagesEvidence Plan: Prepare/Stake Out Building LinesJulius Pecasio100% (1)

- CHN DrugstudyDocument2 pagesCHN DrugstudyNathalie OmalNo ratings yet

- Students Personal Data Sheet FormDocument1 pageStudents Personal Data Sheet FormL 1No ratings yet

- Treatment Plan PortfolioDocument2 pagesTreatment Plan Portfolioapi-518560779No ratings yet

- 2 NdresearchpaperDocument5 pages2 Ndresearchpaperapi-356685046No ratings yet

- The World Bank: IBRD & IDA: Working For A World Free of PovertyDocument25 pagesThe World Bank: IBRD & IDA: Working For A World Free of PovertyManish GuptaNo ratings yet

- Of Mice and MenDocument12 pagesOf Mice and MenAkshitaa PandeyNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3.2.3: Erection III: Steel Construction: Fabrication and ErectionDocument4 pagesLecture 3.2.3: Erection III: Steel Construction: Fabrication and ErectionMihajloDjurdjevicNo ratings yet

- College of Liberal Arts University of LuzonDocument9 pagesCollege of Liberal Arts University of LuzonChristianne Joyse MerreraNo ratings yet

- Understanding Borderline Personality DisorderDocument59 pagesUnderstanding Borderline Personality Disorderaakash atteguppeNo ratings yet