Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Four Concepts of Luxury

Uploaded by

KARISHMA RAJ0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

89 views29 pagesOriginal Title

The Luxury Client

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

89 views29 pagesThe Four Concepts of Luxury

Uploaded by

KARISHMA RAJCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 29

The Luxury Client

LUXURY BRAND MANAGEMENT

MFM-III

Heavy users and day trippers

(also called excursionists)

• Up until 2000, the luxury market had grown

worldwide based on what we call ‘luxury day trippers’

or ‘excursionists’. These people are less wealthy but

are advanced in sociocultural terms, and therefore

allow themselves to occasionally purchase an object

from a luxury brand, motivated by self-indulgence or

hedonism or to celebrate a person or a moment. This

announced the democratization of luxury. Today, it is

no longer the case: the principal volume of the

market is made up of those who buy frequently.

• Why this reversal? From the beginning of the 2000s, the Western

middle classes have been worried about the future, and less

optimistic: progress is no longer automatically associated with

happiness. They fear that their children will have a less pleasant life

than their own. This puts a brake on their occasional consumption

of products perceived as luxury. It is true that in the West,

individuals are ten times richer than the Chinese, for example. But

their income is stagnating, their discretionary purchases are

reduced by rising property prices, energy, service and health costs,

etc. Paradoxically, therefore, they feel themselves to be ‘poor’. In

contrast, young Chinese who see their income perceptibly

increasing are much more optimistic: they feel rich.

• In China, there is no brake on the economic

rise of new population layers, unlike India

where the caste system blocks the mechanism

of climbing the social hierarchy through

economic success. Hence the luxury market in

India is much less dynamic than in China.

The four luxury clienteles

• Beyond the sociodemographic and sociocultural

variables, what is it about luxury that is so seductive?

• Why do clients indulge themselves in luxury?

• What intimate benefits do they gain from it?

• The statistical analysis of the responses by an

international sample of young managers with high

disposable income, asked about the characteristics

that define luxury in their view, make it possible to

identify four concepts of luxury.

• The first type of luxury, according to this

international sample of affluent young executives

with high purchasing power, is the closest to the

average hierarchy emerging from our studies: it

gives prominence to the beauty of the object and

the excellence and uniqueness of the product,

more so than all the other types. The brand most

represent-ative of this type of luxury is Rolls-

Royce, but it also includes Cartier and Hermès.

• The second concept of luxury exalts creativity,

the sensuality of the products; its luxury

‘prototype’ is for example Jean-Paul Gaultier.

• The third vision of luxury values timelessness

and international reputation more than any

other facets; its symbols are Porsche, with its

immutable design, Vuitton and Dunhill. These

are the institutions of the safe choice, of the

certainty of not making a mistake.

• Finally, the fourth type values the feeling of

rarity attached to the possession and

consumption of the brand: in their eyes, the

prototype of the brand purchased by the

select few is Chivas or Mercedes, possession

of which clearly signifies that you have

‘arrived’. The presence of Mercedes as a

symbol of this fourth type of luxury testifies to

the brand’s problems at that time.

Consumers’ four concepts of luxury

A strong axis of segmentation:

relationship with the product or with the logo?

• The four types of clients described above may

be situated in relation to one another along a

key dimension: one that opposes sensitivity to

the logo to sensitivity to the product, the

search for emblematic brands rather than that

for small masterpieces.

• This dimension plays an important role in structuring

and differentiating clients, and even countries,

regarding the relationship to the logo. It is no accident

that luxury brands exhibit their logos. The logo is the

semiotic version of ‘étiquette’, or the code of correct

dress at the Royal Court. This external manifestation

may vary according to circumstances, from more to less

visible, knowing that luxury needs a certain minimal

visibility, even if only discreet, to signal that absolute

separation to which it bears witness.

• The fourth of the above groups is very ‘pro-

logo’: they consume the sign. They need

known and recognized badges to distinguish

themselves from others, to transmit their

success. It is significant that a Mercedes

advertisement in 2007 talked about ‘the car

that has succeeded... like you’.

• The third type is also moved by strong signs,

visible and recognized logos: they enjoy the

magic of the great names and become sure of

themselves through these known brands,

incontrovertible institutions of luxury

worldwide, in the same way that we feel more

at ease when we put on a dinner jacket.

• In contrast, type one clients see themselves as

connoisseurs, aesthetes, capable of

appreciating what is exceptional in a product:

they like the authentic and are sensitive to the

intangibles, the intensity of a rare, shared

moment. As for type two clients, they are more

concerned with showing their individuality,

through choices that set them apart, above the

rest, through the originality of the creator.

A second axis of differentiation:

authentic does not always mean historical

• Luxury is long term. Even if the sales are written

in short-term plans, the luxury brand has time

for itself, much more than a fashion brand.

• For Europeans and many Asian fans, there is not

authenticity without temporal compression. A

brand that has a true history draws an absolute

prestige from it, which does not mean that it

communicates only in a passéiste, traditional

form.

• Hennessy knows how to play with ultra-

modernity, even if its logo is a medallion

representing the historical figure of Mr

Hennessy. The same is true of Veuve Clicquot.

However, young people and most Americans

do not have the same relationship with time:

the authentic, for them, does not require

vintage or historicity.

• An examination of luxury brand strategies clearly shows

these two brand construction models. The first is based

on product quality taken to the extreme, the cult of

product and heritage, History with a capital H, of which

the brand is the modern embodiment. The second is

American in origin, and lacking such a history of its own,

does not hesitate to invent one. These New World brands

have also grasped the importance of the store in creating

an atmosphere and a genuine impression, and of making

the brand’s values palpable there. America invented

Disney and Hollywood – both producers of the imaginary.

A third axis of differentiation:

individualization or integration?

• Finally, the four groups identified above differ

according to a third, classic axis: individuation

on the one hand, and integration on the other.

For the former, luxury is used to show that

they are different: some will not buy a known

champagne brand, but will be in search of

new, creative, audacious brands. For others,

this individuation is achieved through visible

excess.

Luxury by country

• These three axes make it place to situate

countries according to their relationship to

luxury. If France can boast of having given

birth to modern luxury, the luxury market, for

its part, can hardly count on the French. In

fact, in this country, a principle of non-

ostentation reigns, where wealth must be

hidden: we buy Peugeots, not Jaguars.

• France is brought up on a vision of intimate luxury, for

the connoisseur, where history, know-how and detail are

consumed, before enjoying the object on its own terms.

For the French, luxury is pleasure: hence haute cuisine.

Italy is inspired by art.

• The United States wrote into its constitution that the

pursuit of happiness was a duty and a right: in short, you

become happier through consumption rather than

through pleasure. You progress through life through

more comfort, more performance, and more efficiency.

• A diamond is forever, so in addition to

professing love, it is also a good investment.

• A Porsche is beautiful, but with its high

reliability also has a good resale value.

• A Nautor Swan yacht has exceptional

navigation qualities. It is always necessary to

be able to talk of the superiority that the

luxury object confers.

• The emerging countries of luxury (Russia, China,

etc) are very different. Like the USA they are

countries where you can climb the rungs of society

through economic success. Having done so, you

then wish to benefit your clan through it and make

it widely known. It is a more hedonistic, sensual

relationship with luxury, where the signs of value

must be strong, known and recognised: you drink

the special cuvées of the great names of

champagne, as if at a historical potlatch.

Why are the major emerging countries so

avid for luxury?

• Nothing speaks more clearly than etymology. The word

‘luxury’ derives from Latin luxus. How, therefore, do the

Chinese transcribe it? Through two characters (she chi):

the first means ‘important people’, the second means

‘much’. As we can see, luxury in China relates to VIPs:

through luxury you become someone important, or

simply someone. You acquire an immediate distinction.

China is the country where the number of dollar

billionaires shows the highest growth: they will desire

distinctions in line with their success.

Four ways of distinguishing oneself

• In countries where an entirely new moneyed

class is emerging, the Western brands are

somewhat mixed up: a Spanish prêt-à-porter

brand such as Mango will be seen at the same

level as Boss, or even Bulgari or Davidoff.

• In India, the same RISC survey elicited the names of

Park Avenue, Wills Lifestyle, Rolex and Omega. The

first two are local brands: the first is a clothing

brand, the second a textile extension of a cigarette

brand (Wills) that is well known but expensive by

Indian standards – at the level of Marlboro. This is

why the salespeople of Western luxury houses in

India are half-salespeople, half-PR agents: they

must spend much of their time explaining and

educating as to why the price is so high.

• An expensive product is not necessarily a luxury

product, it requires a cultural transformation

• to turn it into a vehicle of social distinction and

stratification. In order to appreciate it you need the

keys of this culture, and therefore an education. To

date in the moneyed classes of India, 30 per cent of

the people have acquired this culture, and 70 per

cent only wish to signal that they have arrived. This is

characteristic of emerging countries, such as China

and Russia.

What luxury evokes

• What explains the attachment that Asian consumers feel for

luxury? Above all, the exceptional economic growth and the size of

the potential market (linked to the emergence of a sizeable middle

class). Through loss of culture, and denial of their own history,

certain countries have no other standard by which to measure the

value of things other than their price and reputation.

• Money becomes the standard of all things. Moreover, it testifies

not to your heritage, but to the fact of your own success. It is a

measure of your merit. We would add that luxury is the medal of

this merit. The old Marxist class struggle is replaced by the

individual struggle for class. For lack of culture, international luxury

brands have become the language of immediate distinction

You might also like

- Luxury Brand Creation and ManagementDocument22 pagesLuxury Brand Creation and Managementsuruchi singhNo ratings yet

- Brand Valuation Models and Luxury Brand StrategiesDocument70 pagesBrand Valuation Models and Luxury Brand Strategiesbhuvan mehraNo ratings yet

- Why Men Like Straight Lines and Women Like Polka Dots: Gender and Visual PsychologyFrom EverandWhy Men Like Straight Lines and Women Like Polka Dots: Gender and Visual PsychologyNo ratings yet

- The Soul of the New Consumer (Review and Analysis of Windham and Orton's Book)From EverandThe Soul of the New Consumer (Review and Analysis of Windham and Orton's Book)No ratings yet

- The New Religious Image of Urban America, Second Edition: The Shopping Mall as Ceremonial CenterFrom EverandThe New Religious Image of Urban America, Second Edition: The Shopping Mall as Ceremonial CenterNo ratings yet

- A Portrait of the Auteur as Fanboy: The Construction of Authorship in Transmedia FranchisesFrom EverandA Portrait of the Auteur as Fanboy: The Construction of Authorship in Transmedia FranchisesNo ratings yet

- Consumer Culture: Selected EssaysFrom EverandConsumer Culture: Selected EssaysDoctor Gjoko MuratovskiNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Consumption of Luxury Goods Example of Fashion Luxury Market in RussiaDocument26 pagesSymbolic Consumption of Luxury Goods Example of Fashion Luxury Market in RussiaAndreeaAnna18No ratings yet

- Luxury Brands in The Digital AgeDocument6 pagesLuxury Brands in The Digital Ageminihool100% (1)

- Pre-Loved Luxury - Identifying The Meanings of Second-Hand Luxury PossessionsDocument28 pagesPre-Loved Luxury - Identifying The Meanings of Second-Hand Luxury PossessionsSita W. Suparyono100% (1)

- Luxury and Social Media FINALDocument66 pagesLuxury and Social Media FINALVasilisa SoloNo ratings yet

- Luxury BrandExclusivity Strategies AnIllustration of A CulturalCollaboration PDFDocument5 pagesLuxury BrandExclusivity Strategies AnIllustration of A CulturalCollaboration PDFSneha KarpeNo ratings yet

- European Luxury Goods Hard Luxury - Markets, Players, OpportunitiesDocument182 pagesEuropean Luxury Goods Hard Luxury - Markets, Players, Opportunitiesso_leil8No ratings yet

- Moeran, Brian. (2006) - More Than Just A Fashion Magazine.Document22 pagesMoeran, Brian. (2006) - More Than Just A Fashion Magazine.Carolina GutierrezNo ratings yet

- GucciLouisVuitton Vertu CaseStudyDocument9 pagesGucciLouisVuitton Vertu CaseStudyzana_georgiana747No ratings yet

- Co-Creating Value For Luxury Brands PDFDocument8 pagesCo-Creating Value For Luxury Brands PDFSourabh SinghNo ratings yet

- Redefining LuxuryDocument32 pagesRedefining LuxurySneha Karpe100% (3)

- Okonkwo, Uche. The Luxury Brand Strategy ChallengeDocument3 pagesOkonkwo, Uche. The Luxury Brand Strategy ChallengeMiguel Angelo HemzoNo ratings yet

- Comparing and Analysing CRM (GRP - D)Document44 pagesComparing and Analysing CRM (GRP - D)kallikaNo ratings yet

- Merchandising PortfolioDocument140 pagesMerchandising PortfolioHyunJuPark100% (2)

- CSM CMD Certification GuideDocument20 pagesCSM CMD Certification GuideGenti El100% (1)

- Chap 2 Part 1Document8 pagesChap 2 Part 1ariaNo ratings yet

- The State of Fashion Forbes Pankti Mehta Kadakia May 13 2019Document10 pagesThe State of Fashion Forbes Pankti Mehta Kadakia May 13 2019SophieNo ratings yet

- How Fashion Travels The Fashionable Ideal in The Age of Instagram (OCR) PDFDocument25 pagesHow Fashion Travels The Fashionable Ideal in The Age of Instagram (OCR) PDFVlad AghagulianNo ratings yet

- Trading Up - How New Luxury Goods Appeal to CustomersDocument1 pageTrading Up - How New Luxury Goods Appeal to CustomersethernalxNo ratings yet

- An Bernadette Corp Groy ReadingDocument8 pagesAn Bernadette Corp Groy ReadingNigel Lee-YangNo ratings yet

- Luxury Perfume IndustryDocument4 pagesLuxury Perfume IndustryRicardo GrederNo ratings yet

- Consumer-Brand Relationships in Step-Down Line Extensions of Luxury and Designer BrandsDocument25 pagesConsumer-Brand Relationships in Step-Down Line Extensions of Luxury and Designer BrandsSohaib SangiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3 The PowerDocument3 pagesJurnal 3 The PowerYonaJulia AprinaNo ratings yet

- The Development of High-End Brands of Streetwear Fashion Styles Among Millenials in Semarang City of IndonesiaDocument10 pagesThe Development of High-End Brands of Streetwear Fashion Styles Among Millenials in Semarang City of IndonesiaAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- BoF The Companies Culture Issue Spring 2014Document48 pagesBoF The Companies Culture Issue Spring 2014Ioana DobrinNo ratings yet

- C01 Vestiaire CollectiveDocument13 pagesC01 Vestiaire CollectiveVitor ANo ratings yet

- Avant-Garde Fashion - A Case Study of Martin MargielaDocument13 pagesAvant-Garde Fashion - A Case Study of Martin MargielaNacho VaqueroNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism Stylistic Change in Fashion DesignDocument16 pagesPostmodernism Stylistic Change in Fashion Designurska100% (1)

- Luxury in VietnamDocument5 pagesLuxury in VietnamMelina NguyenNo ratings yet

- L3Industrysegmentation 2014Document27 pagesL3Industrysegmentation 2014albertfisher100% (1)

- 8ps of Luxury BrandingDocument10 pages8ps of Luxury BrandingbatandrobinNo ratings yet

- Accessorize Brand PrismDocument13 pagesAccessorize Brand PrismGaurav RawatNo ratings yet

- Gender Neutral Clothing - RMDocument14 pagesGender Neutral Clothing - RMKritika DhawanNo ratings yet

- Mind Mapping AnalysisDocument1 pageMind Mapping AnalysisRanjith ARNo ratings yet

- Consumer Attitude Segments Toward Luxury: A 20-Country StudyDocument14 pagesConsumer Attitude Segments Toward Luxury: A 20-Country StudyLu CeNo ratings yet

- Corporate Branding, Emotional Attachment and Brand Loyalty The Case of Luxury Fashion BrandingDocument24 pagesCorporate Branding, Emotional Attachment and Brand Loyalty The Case of Luxury Fashion Brandingdhrupody4No ratings yet

- Anti Laws of Luxury MarketingDocument7 pagesAnti Laws of Luxury MarketingPriyanka AroraNo ratings yet

- New Collection Launch - Marketing Plan 22.10.2009Document60 pagesNew Collection Launch - Marketing Plan 22.10.2009Huyen Nhung NguyenNo ratings yet

- Burberry Aduit Final DraftDocument15 pagesBurberry Aduit Final Draftapi-275576169No ratings yet

- Luxury For The Masses: HBR Article by Michael J. Silverstein & Neil FiskeDocument36 pagesLuxury For The Masses: HBR Article by Michael J. Silverstein & Neil FiskeShivani SalujaNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Development Strategy For Louis VuittonDocument15 pagesSustainable Development Strategy For Louis VuittonEngrAbeer ArifNo ratings yet

- Louis Vuitton: The Strongest Luxury BrandDocument12 pagesLouis Vuitton: The Strongest Luxury BrandvipuljagrawalNo ratings yet

- Ning A Solution For Design Piracy: Considering Intellectual Property Law in The Global Context of Fast FashionDocument33 pagesNing A Solution For Design Piracy: Considering Intellectual Property Law in The Global Context of Fast FashionIraNo ratings yet

- Luxury Marketing: Critical Evaluation of Chanel &hermèsDocument48 pagesLuxury Marketing: Critical Evaluation of Chanel &hermèsMadalina LorelaiNo ratings yet

- Review Questions Case StudyDocument45 pagesReview Questions Case StudyVõ Thị Tú AnhNo ratings yet

- American ApparelDocument13 pagesAmerican ApparelBilal ShabarekNo ratings yet

- Market ResearchDocument89 pagesMarket ResearchSankeitha SinhaNo ratings yet

- Global Food and Drink Trends 2021 Shared by WorldLine TechnologyDocument26 pagesGlobal Food and Drink Trends 2021 Shared by WorldLine TechnologyNghi TranNo ratings yet

- The Current and Future Prospect of Streetwear A Study Based On Various Textile WearDocument9 pagesThe Current and Future Prospect of Streetwear A Study Based On Various Textile Wear078Saurabh RajputNo ratings yet

- Kapferer Model Brand Identity Prism 1228214291948754 9Document31 pagesKapferer Model Brand Identity Prism 1228214291948754 9Saquib AhmadNo ratings yet

- The State of Fashion 2021 VFDocument235 pagesThe State of Fashion 2021 VFZoya ShahidNo ratings yet

- Louis VuittonDocument3 pagesLouis VuittonRimon MahiNo ratings yet

- Russia's Lucrative Luxury Goods MarketDocument8 pagesRussia's Lucrative Luxury Goods MarketMauro VirelloNo ratings yet

- JD - Marketing Specialist 2021Document1 pageJD - Marketing Specialist 2021KARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Ruchi Ratan - Resume - NiftDocument1 pageRuchi Ratan - Resume - NiftKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Internship ReportDocument74 pagesInternship ReportKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- National Institute of Fashion Technology Patna: EntertainmentDocument1 pageNational Institute of Fashion Technology Patna: EntertainmentKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Final GP Report - PoojaDocument65 pagesFinal GP Report - PoojaKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Buying Process for Kidswear at V-Mart RetailDocument109 pagesUnderstanding the Buying Process for Kidswear at V-Mart RetailKARISHMA RAJ100% (1)

- How Is Leather MadeDocument3 pagesHow Is Leather MadeKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- GRADUATION RESEARCH PROJECT DeboDocument2 pagesGRADUATION RESEARCH PROJECT DeboKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Swot Analysis: Strengths WeaknessDocument6 pagesSwot Analysis: Strengths WeaknessKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Nike Strategy Analysis, PDFDocument26 pagesNike Strategy Analysis, PDFSimran SinghNo ratings yet

- Investment in Life Insurance: A Study of Consumer BehaviourDocument40 pagesInvestment in Life Insurance: A Study of Consumer BehaviourKARISHMA RAJ100% (1)

- Simran Singh, Big Data End Term AssignmentDocument6 pagesSimran Singh, Big Data End Term AssignmentKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- The Growth of E-Commerce and Its Impact On The Fast Fashion RetailersDocument42 pagesThe Growth of E-Commerce and Its Impact On The Fast Fashion RetailersAkhil AntoNo ratings yet

- Personal SellingDocument6 pagesPersonal SellingKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Central SWOT Analysis: Internal & External FactorsDocument1 pageCentral SWOT Analysis: Internal & External FactorsKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Ruchi Ratan - IdmDocument34 pagesRuchi Ratan - IdmKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

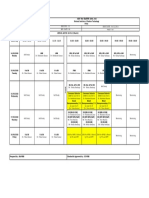

- MFM-III, BATCH: 2019-21 (Week-6) : Prepared By: RA-FMS Checked & Approved By: CC-FMSDocument1 pageMFM-III, BATCH: 2019-21 (Week-6) : Prepared By: RA-FMS Checked & Approved By: CC-FMSKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 PDFDocument1 pageAssignment 2 PDFKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

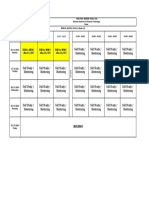

- Week-11Document1 pageWeek-11KARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Future Group Central Mall Internship ReportDocument123 pagesFuture Group Central Mall Internship ReportKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- End Term Jury Brief - MFM IIIDocument1 pageEnd Term Jury Brief - MFM IIIKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Tuition Fee Circular (July 20 To Dec 20)Document2 pagesTuition Fee Circular (July 20 To Dec 20)KARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- NIFT Patna MFM-III scheduleDocument1 pageNIFT Patna MFM-III scheduleKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Applying 5S Method On Trims Stores Docum PDFDocument11 pagesApplying 5S Method On Trims Stores Docum PDFAbhinav AshishNo ratings yet

- Application of Lean Manufacturing Tools in Garment IndustryDocument7 pagesApplication of Lean Manufacturing Tools in Garment IndustryVishwanath KrNo ratings yet

- Jacket Spec Sheet By-Amit SinghDocument15 pagesJacket Spec Sheet By-Amit Singhamit_k10289% (9)

- 1ST Assignment - Ruchi RatanDocument8 pages1ST Assignment - Ruchi RatanKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- End Term Jury Brief - MFM IIIDocument1 pageEnd Term Jury Brief - MFM IIIKARISHMA RAJNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Amul Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument5 pagesCase Study - Amul Corporate Social ResponsibilityKARISHMA RAJ75% (4)

- 15 Inspiring Mission and Vision StatementsDocument14 pages15 Inspiring Mission and Vision StatementsKARISHMA RAJ100% (1)

- Ancient Draping Styles of Egypt, Greece and RomeDocument8 pagesAncient Draping Styles of Egypt, Greece and Romekavindu gunarathneNo ratings yet

- La moda españolaDocument4 pagesLa moda españolaSergioNo ratings yet

- BrandsDocument6 pagesBrandsEverythingNo ratings yet

- Unveiling Fashion Business, Culture, and Identity in The Most Glamorous Industry by Frédéric Godart (Auth.)Document223 pagesUnveiling Fashion Business, Culture, and Identity in The Most Glamorous Industry by Frédéric Godart (Auth.)Daniela Arroyo100% (1)

- Fashion Design Technology Vol I of II TTDocument195 pagesFashion Design Technology Vol I of II TTcozmeicmodsNo ratings yet

- Smith Wire Manufactures Custom Wire FramesDocument45 pagesSmith Wire Manufactures Custom Wire FramesJeffrey Michael AtencioNo ratings yet

- Differences in Traditional Asian CostumesDocument5 pagesDifferences in Traditional Asian CostumesShin Pyae Chan Min MaungNo ratings yet

- Festive Fashion - Spring Styling Tips For Kids' Easter AttireDocument3 pagesFestive Fashion - Spring Styling Tips For Kids' Easter AttireseocutiepatootieNo ratings yet

- Complete - List - of - Footwear - Tested - Nov - 11 - 2022Document18 pagesComplete - List - of - Footwear - Tested - Nov - 11 - 2022Dado TorcisoNo ratings yet

- NCERT Class 12 Home Science Chapter 13 Fashion Design and MerchandisingDocument14 pagesNCERT Class 12 Home Science Chapter 13 Fashion Design and MerchandisingPratham PawarNo ratings yet

- Handle With CareDocument2 pagesHandle With CareThùy DươngNo ratings yet

- The List of The Item For Enhance Weapons and Armours in VindictusDocument16 pagesThe List of The Item For Enhance Weapons and Armours in VindictusAlfihri Al'iiesarNo ratings yet

- Elle Canada 04-2023 - ZendayaDocument116 pagesElle Canada 04-2023 - ZendayaamandaNo ratings yet

- LISTA DE PRECIOS AGOSTO 2022Document32 pagesLISTA DE PRECIOS AGOSTO 2022maria guadalupe salmanNo ratings yet

- Nivel 4 Unidad 11Document11 pagesNivel 4 Unidad 11YaneMercadoMezaNo ratings yet

- Term End Exam Time Table Design Faculty Dec 2022Document1 pageTerm End Exam Time Table Design Faculty Dec 2022Shubhi KothariNo ratings yet

- Wales Bonner - Claudio & EshaanDocument44 pagesWales Bonner - Claudio & EshaanEshaan ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Presentation ON MAXDocument14 pagesPresentation ON MAXSharmila BalanNo ratings yet

- Y2 Module 2 Drafting and Cutting Pattern For Ladies' Casual Apparel Part 2Document45 pagesY2 Module 2 Drafting and Cutting Pattern For Ladies' Casual Apparel Part 2Artdevil CesarNo ratings yet

- Bodo Traditional Dress - Mousumi MochaharyDocument3 pagesBodo Traditional Dress - Mousumi MochaharyAVINASH YADAVNo ratings yet

- Automated Belt to Jacket Production Monitoring and ReportingDocument32 pagesAutomated Belt to Jacket Production Monitoring and Reportingvidit MishraNo ratings yet

- Evolution of EyewearDocument25 pagesEvolution of EyewearAbhiraj SinghNo ratings yet

- List Importer UK Garments SectorDocument8 pagesList Importer UK Garments SectorKharisma Rizky Nugraha100% (4)

- Unit 6: - Image and Identity Word MeaningDocument3 pagesUnit 6: - Image and Identity Word Meaningmher001No ratings yet

- Men S Accessories & Footwear Colour Trend Concepts A W 21 22Document18 pagesMen S Accessories & Footwear Colour Trend Concepts A W 21 22Raquel Mantovani100% (1)

- Retail Analysis: Women's Footwear & Accessories Summer 2021Document27 pagesRetail Analysis: Women's Footwear & Accessories Summer 2021Raquel MantovaniNo ratings yet

- Asm656 Individual Assignment 1 (Sharina Binti Sopian)Document13 pagesAsm656 Individual Assignment 1 (Sharina Binti Sopian)Sharina SopianNo ratings yet

- Armaf ClonesDocument3 pagesArmaf ClonesRaghav Randar100% (3)

- The Evolution of Filipino FashionDocument25 pagesThe Evolution of Filipino FashionPamela Joy Sangal100% (2)

- Quick Grammar, Vocabulary and Pronunciation TestDocument3 pagesQuick Grammar, Vocabulary and Pronunciation TestAnna GeneraliukNo ratings yet