Professional Documents

Culture Documents

11a. Blood Transfusion

Uploaded by

Muwanga faizo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

42 views28 pagesThis document provides information about blood transfusion, including:

1. It describes the process of blood donation, testing, and separation into components like packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate.

2. It outlines the major blood group systems, ABO and Rh, and explains the risks of transfusion reactions if incompatible blood is transfused.

3. It lists the common indications for blood transfusion like acute blood loss, perioperative anemia, and symptomatic chronic anemia.

Original Description:

Surgery

Original Title

11a. Blood transfusion

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document provides information about blood transfusion, including:

1. It describes the process of blood donation, testing, and separation into components like packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate.

2. It outlines the major blood group systems, ABO and Rh, and explains the risks of transfusion reactions if incompatible blood is transfused.

3. It lists the common indications for blood transfusion like acute blood loss, perioperative anemia, and symptomatic chronic anemia.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

42 views28 pages11a. Blood Transfusion

Uploaded by

Muwanga faizoThis document provides information about blood transfusion, including:

1. It describes the process of blood donation, testing, and separation into components like packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate.

2. It outlines the major blood group systems, ABO and Rh, and explains the risks of transfusion reactions if incompatible blood is transfused.

3. It lists the common indications for blood transfusion like acute blood loss, perioperative anemia, and symptomatic chronic anemia.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 28

BLOOD TRANSFUSION

DR KYOMUKAMA AMAGARA LAUBEN

MMED SURGERY, MBChB & DCM

MARCH 2019

Introduction to transfusion

• The transfusion of blood and blood products has become

common place since the first successful transfusion in 1818.

• Although the incidence of severe transfusion reactions and

infections is now very low, in recent years it has become

apparent that there is an immunological price to be paid

from the transfusion of heterologous blood, leading to

increased morbidity and decreased survival in certain

population groups (trauma, malignancy).

• Supplies are also limited, and therefore the use of blood

and blood products must always be judicious and justifiable

for clinical need

HISTRORY OF TRANSFUSION

Blood and blood products

• Blood is collected from donors.

DONORS.

• These are screened before donating

– For potential infections that may harm patients

– To prevent possible harm to donors

• A unit is up to 450 mL of blood is drawn, a maximum of three times per year.

• Each unit is tested for evidence of;

– hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV-1, HIV-2 and syphilis.

• Donations are leukodepleted as a precaution against variant Creutzfeldt–

Jakob disease (this may also reduce the immunogenicity of the transfusion).

• The ABO and rhesus D blood groups are determined, as well as the presence

of irregular red cell antibodies.

• The blood is then processed into subcomponents.

Donor recruitment guideline

1. General appearance: the prospective donor shall appear to be in good

physical and mental health.

2. Age: donors shall be between 18 and 60 years of age.

3. Haemoglobin: Hb shall be not less than 12.5 g/dL for males and 11.5

g/dL for females.

4. Weight: minimum 45 kg.

5. Blood pressure: systolic and diastolic pressures shall be normal

(systolic: 100‐140 mm Hg and diastolic: 60‐90 mm Hg is

recommended), without the aid of anti‐hypertensive medication.

6. Temperature: oral temperature shall not exceed 37.5oC/99.5oF.

7. Pulse: pulse shall be between 60 and 100 beats per minute and regular.

8. Donation interval: the interval between blood donations shall be 3 to 4

months.

WHOLE BLOOD

• Whole blood is now rarely available in civilian

practice because it has been seen as an

inefficient use of the limited resource.

• However, whole blood transfusion has

significant advantages over packed cells as it

is coagulation factor rich and, if fresh, more

metabolically active than stored blood.

Blood components:

A blood component is a constituent of blood, separated from whole

blood, such as:

Red cell concentrate

Plasma

Platelet concentrate

Cryoprecipitate, prepared from fresh frozen plasma; rich in Factor

VIII and fibrinogen

A plasma derivative is made from human plasma proteins prepared

under pharmaceutical manufacturing conditions, such as:

Albumin

Coagulation factor concentrates

Immunoglobulin

Whole blood

Description: Indications:

•450 mL whole blood in 63 mL Red cell replacement in acute blood loss

anticoagulant‐preservative solution of with hypovolaemia.

which Hb will be approximately Exchange transfusion.

•1.2 g/dL and haematocrit (Hct) 35‐45%

with no functional platelets or labile

coagulation factors (V and VIII) when

stored at +2°C to +6°C. Contraindications:

•Risk of volume overload in patients with:

Infection risk:

•Capable of transmitting an agent present Chronic anaemia.

in cells or plasma which was undetected Incipient cardiac failure.

during routine screening for TTIs, i.e. HIV,

hepatitis B & C, syphilis and malaria. Administration:

Storage: Must be ABO and RhD compatible with

•Between +2°C and +6°C in an approved the recipient.

blood bank refrigerator, fitted with a Never add medication to a unit of

temperature monitor and alarm. blood.

Complete transfusion within 4 hours of

commencement.

1. Packed red blood cells.

• Packed red blood cells are spun-down and

concentrated packs of red blood cells.

• Each unit is approximately 330 mL and has a

haematocrit of 50–70%. Packed cells are stored

in a SAG-M solution (saline–adenine–glucose–

mannitol) to increase shelf life to 5 weeks at 2–

6°C.

• Use of citrate phosphate dextrose solutions CPD

shelf life is 2-3 weeks

2. Fresh-frozen plasma.

• Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) is rich in coagulation factors

and is removed from fresh blood and stored at −40 to

−50°C with a 2-year shelf life.

• It is the first-line therapy in the treatment of coagulopathic

hemorrhage (see below under Management of

coagulopathy).

• Rhesus D-positive FFP may be given to a rhesus D-

negative woman although it is possible for sero-conversion

to occur with large volumes owing to the presence of red

cell fragments, and Rh-D immunization should be

considered.

3. Cryoprecipitate.

• Cryoprecipitate is a supernatant

precipitate of FFP and is rich in

factor VIII and fibrinogen. It is stored

at −30°C with a 2-year shelf life. It is

given in low fibrinogen states or

factor VIII deficiency.

4. Platelets.

• Platelets are supplied as a pooled • Aspirin therapy rarely poses a

platelet concentrate and contain problem but control of

about 250 × 109/L. haemorrhage on the more potent

• Platelets are stored on a special platelet inhibitors can be extremely

agitator at 20–24°C and have a difficult.

shelf life of only 5 days. • Patients on clopidogrel who are

• Platelet transfusions are given to actively bleeding and undergoing

patients with thrombocytopenia or major surgery may require almost

with platelet dysfunction who are continuous infusion of platelets

bleeding or undergoing surgery. during the course of the procedure.

• Patients are increasingly presenting • Arginine vasopressin or its

on antiplatelet therapy such as analogues (DDAVP) have also

aspirin or clopidogrel for reduction been used in this patient group,

of cardiovascular risk. although with limited success.

5.Prothrombin complex concentrates.

• Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC) are

highly purified concentrates prepared from

pooled plasma.

• They contain factors II, IX and X. Factor VII

may be included or produced separately.

• It is indicated for the emergency reversal of

anticoagulant (warfarin) therapy in

uncontrolled hemorrhage.

Autologous blood:

• It is possible for patients undergoing elective

surgery to predonate their own blood up to 3

weeks before surgery for retransfusion during

the operation.

• Similarly, during surgery blood can be

collected in a cell-saver which washes and

collects red blood cells which can then be

returned to the patient.

Indications for blood transfusion

• Blood transfusions should be avoided if possible, and many previous

uses of blood and blood products are now no longer considered

appropriate.

The indications for blood transfusion are as follows:

1. Acute blood loss, to replace circulating volume and maintain

oxygen delivery

2. Perioperative anaemia, to ensure adequate oxygen delivery during

the perioperative phase

3. Symptomatic chronic anaemia, without haemorrhage or impending

surgery.

PERIOPERATIVE RED BLOOD CELL

TRANSFUSION CRITERIA

• HB > 10g/dl is associated with increased morbidity

and mortality and recent lower targets are used.

Below are triggers to transfuse

•

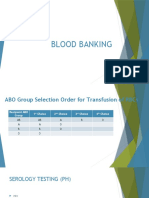

BLOOD GROUPS &CROSS-MATCHING

• Human red cells have on their cell surface

many different antigens.

• Two groups of antigens are of major

importance in surgical practice;

1. The ABO.

2. Rhesus systems.

ABO SYSTEM

• These proteins are strongly antigenic and are associated with naturally

occurring antibodies in the serum.

• The system consists of three allelic genes – A, B and O – which control

synthesis of enzymes that add carbohydrate residues to cell surface

glycoproteins. A and B genes add specific residues while the O gene is an

amorph and does not transform the glycoprotein.

• The system allows for six possible genotypes although there are only four

phenotypes.

• Naturally occurring antibodies are found in the serum of those lacking the

corresponding antigen.

• Blood group O is the universal donor type as it contains no antigens to

provoke a reaction.

• Conversely, group AB individuals are ‘universal recipients’ and can

receive any ABO blood type because they have no circulating antibodies.

ABO BLOOD GROUP SYSTEM.

RHESUS SYSTEM

• The rhesus D (Rh(D)) antigen is strongly antigenic and is present in

approximately 85% of the population in the UK.

• Antibodies to the D antigen are not naturally present in the serum of

the remaining 15% of individuals, but their formation may be

stimulated by the transfusion of Rh-positive red cells, or acquired

during delivery of a Rh(D)-positive baby.

• Acquired antibodies are capable, during pregnancy, of crossing the

placenta and, if present in a Rh(D)-negative mother, may cause severe

haemolytic anaemia and even death (hydrops fetalis) in a Rh(D)-

positive fetus in utero.

• The other minor blood group antigens may be associated with naturally

occurring antibodies, or may stimulate the formation of antibodies on

relatively rare occasions.

TRANSFUSION REACTIONS

• If antibodies present in the recipient’s serum are incompatible with the

donor’s cells, a transfusion reaction will result.

• This usually takes the form of an acute haemolytic reaction. Severe

immune-related transfusion reactions due to ABO incompatibility

result in potentially fatal complement-mediated intravascular

haemolysis and multiple organ failure.

• Transfusion reactions from other antigen systems are usually milder

and self-limiting. Febrile transfusion reactions are non-haemolytic

and are usually caused by a graft-versus-host response from

leukocytes in transfused components.

• Such reactions are associated with fever, chills or rigors. The blood

transfusion should be stopped immediately. This form of transfusion

reaction is rare with leukodepleted blood.

Cross-matching

• To prevent transfusion reactions, all transfusions are preceded by ABO and rhesus typing of

both donor and recipient blood to ensure compatibility.

• The recipient’s serum is then mixed with the donor’s cells to confirm ABO compatibility

and to test for rhesus and any other blood group antigen–antibody reaction.

• Full cross-matching of blood may take up to 45 minutes in most laboratories. In more

urgent situations, ‘type specific’ blood is provided which is only ABO/rhesus matched and

can be issued within 10–15 minutes.

• Where blood must be given emergently, group O (universal donor) blood is given (O− to

females, O+ to males).

• When blood transfusion is prescribed and blood is administered, it is essential that the

correct patient receives the correct transfusion.

• Two healthcare personnel should check the patient details against the prescription and the

label of the donor blood. In addition, the donor blood serial number should also be

checked against the issue slip for that patient.

• Provided these principles are strictly adhered to the number of severe and fatal ABO

incompatibility reactions can be minimized.

COMPLICATIONS OF BLOOD TRANSFUSION

Complications from a single Complications from massive

transfusion transfusion

i. Incompatibility hemolytic transfusion i. Coagulopathy

reaction

ii. Febrile transfusion reaction ii. Hypocalcaemia

iii. Allergic reaction iii. Hyperkalemia

iv. Infection:

Bacterial infection (usually due to faulty iv. Hypokalemia

storage)

Hepatitis v. Hypothermia.

HIV vi. iron overload. ( each unit

Malaria

v. Air embolism

contains 250g of iron)

vi. Thrombophlebitis

vii. Transfusion-related acute lung injury

(usually from FFP).

Management of coagulopathy

• It occurs commonly following massive transfusion.

• Damage control resuscitation (DCR) for actively bleeding patients aims at

preventing dilutional coagulopathy

• Transfusion of matching red blood cells packs with plasma and platelets ensures

balanced transfusion to prevent coagulopathy

• Based on moderate evidence, when red cells are transfused for active haemorrhage,

it is best to match each red cell unit with one unit of FFP and one of platelets (1:1:1).

This will reduce the incidence and severity of subsequent dilutional coagulopathy

• Manage underlying coagulopathy besides 1:1:1 regime

• Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic helps to prevent coagulopathy.

• Monitoring of coagulation using

– Thromboelastometry

– Clotting time

– fibrinogen

Blood substitutes

• These are attractive alternative to the costly

process of donating, checking, storing and

administering blood, especially given the

immunogenic and potential infectious

complications associated with transfusion

• Blood substitutes are either biomimetic or

abiotic.

Blood substitutes

Biomimetic substitutes Abiotic substitutes

• These mimic the standard • Abiotic substitutes are

oxygen-carrying capacity of the synthetic oxygen carriers

blood and are haemoglobin

and are currently primarily

based.

perfluorocarbon based.

• Haemoglobin is seen as the

obvious candidate for developing • Second-generation

an effective blood substitute. perfluorocarbon emulsions

• Various engineered molecules are also showing otential in

are under clinical trials, and are clinical trials.

based on human, bovine or

recombinant technologies.

REFERENCES

• Bailey and loves short practices of surgery.

• Glen J, Constanti M, Brohi K; Guideline

Development Group. Assessment and initial

management of major trauma: summary of

NICE guidance. BMJ 2016; 353: i3051.

• Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V et al. The

uropean guideline on management of major

bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma:

fourth edition. Crit Care 2016; 20: 100.

questions

1. A24-year-old woman is scheduled for an elective

cholecystectomy. The best method of identifying

a potential bleeder is which of the following?

A. Platelet count

B. A complete history and physical examination

C. Bleeding time

D. Lee-White clotting time

E. Prothrombin time (PT)

You might also like

- Blood Transfusion: DR - Arun Walwekar Assistant Professor Department of General Surgery Kims HubliDocument23 pagesBlood Transfusion: DR - Arun Walwekar Assistant Professor Department of General Surgery Kims HubliAnkith M.RNo ratings yet

- Blood and Its ComponentsDocument30 pagesBlood and Its ComponentskushalNo ratings yet

- Blood Groups, Blood Components, Blood Transfusion PresentationDocument50 pagesBlood Groups, Blood Components, Blood Transfusion PresentationAashish Gautam100% (1)

- 4 Blood ProductsDocument11 pages4 Blood ProductsGampa VijaykumarNo ratings yet

- Blood TransusionDocument21 pagesBlood TransusionOsama Fadel ahmedNo ratings yet

- Blood Component TherapyDocument73 pagesBlood Component TherapySaikat Prasad DattaNo ratings yet

- ICU Blood Transfusion & Electrolytes DisturbanceDocument26 pagesICU Blood Transfusion & Electrolytes Disturbancef6080683No ratings yet

- Principles of Blood Transfusion 2Document21 pagesPrinciples of Blood Transfusion 2dhivya singhNo ratings yet

- Blood Products. Preparation of Blood ComponentsDocument32 pagesBlood Products. Preparation of Blood ComponentsSanthiya MadhavanNo ratings yet

- Blood and Blood ProductsDocument52 pagesBlood and Blood Productswellawalalasith100% (1)

- TransfusionDocument19 pagesTransfusionSrishti SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Blood and Blood Product TransfusionDocument75 pagesBlood and Blood Product TransfusionHaileyesus NatnaelNo ratings yet

- Blood ProductsDocument70 pagesBlood Productsjadhamade339No ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion ClassDocument61 pagesBlood Transfusion ClassshikhaNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument59 pagesBlood Transfusionpranalika .................76% (17)

- Blood TransfusionDocument57 pagesBlood Transfusionibzshan_No ratings yet

- Blood ProductsDocument41 pagesBlood ProductsrijjorajooNo ratings yet

- Jenny A. Cruz Level IV Block 1 Group 4B Blood TransfusionDocument5 pagesJenny A. Cruz Level IV Block 1 Group 4B Blood TransfusionRosalinda Aquino CruzNo ratings yet

- Blood Components - DR. ETU-EFEOTOR T. P.Document40 pagesBlood Components - DR. ETU-EFEOTOR T. P.Princewill Seiyefa100% (1)

- Blood & Blood ProductsDocument126 pagesBlood & Blood ProductsdrprasadingleyNo ratings yet

- Blood and Blood ComponentsDocument51 pagesBlood and Blood ComponentsMinlun ChongloiNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument28 pagesBlood TransfusionPORTRAIT OF A NURSENo ratings yet

- Surgery of Kidney Ureter and VaricoseDocument55 pagesSurgery of Kidney Ureter and VaricoseSaurabh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Blood Grouping and BankingDocument41 pagesBlood Grouping and BankingChipego NyirendaNo ratings yet

- 3.2 Dr. Teguh. 2019 TT Use of Blood Component in Paed Transfusion MACPLAMDocument31 pages3.2 Dr. Teguh. 2019 TT Use of Blood Component in Paed Transfusion MACPLAMRini WidyantariNo ratings yet

- Blood & Blood Products OnlyDocument54 pagesBlood & Blood Products OnlydrprasadingleyNo ratings yet

- Blood Component TherapyDocument8 pagesBlood Component TherapyquerokeropiNo ratings yet

- Blood Components: D.) Washed Rbcs and Frozen/Deglycerolized RbcsDocument3 pagesBlood Components: D.) Washed Rbcs and Frozen/Deglycerolized RbcsGerarld Immanuel KairupanNo ratings yet

- Blood GroopsDocument32 pagesBlood GroopsAbbas AliNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion: Moderator: DR - Ibrahim Qudaisat Presented by Murad SataryDocument46 pagesBlood Transfusion: Moderator: DR - Ibrahim Qudaisat Presented by Murad SataryMorad SatariNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument32 pagesBlood TransfusionsallaxleyNo ratings yet

- 6.blood Transfusion, Hemostasis & Coagulation DisordersDocument42 pages6.blood Transfusion, Hemostasis & Coagulation DisordersEyouel TadesseNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument58 pagesBlood Transfusionmsat72100% (12)

- Blood Transfusion 2Document12 pagesBlood Transfusion 2Helene AlawamiNo ratings yet

- Blood Products and Their UsesDocument28 pagesBlood Products and Their UsesJeevitha Vanitha100% (1)

- 11 Peri Operative CareDocument43 pages11 Peri Operative CareAdnan MaqboolNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument74 pagesBlood Transfusiontefesih tube ተፈስሕ ቲዮብNo ratings yet

- Blood ComponenetsDocument41 pagesBlood Componenetsnighat khanNo ratings yet

- Information Sheet For Candidate: General CommentsDocument4 pagesInformation Sheet For Candidate: General Commentsfire_n_iceNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument31 pagesBlood TransfusionAbdul HafeezNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument104 pagesBlood TransfusionrodelagapitoNo ratings yet

- 2-Transfusion of Blood and Blood ProductsDocument47 pages2-Transfusion of Blood and Blood ProductsAiden JosephatNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion in Pediatrics - Dr. RiniDocument55 pagesBlood Transfusion in Pediatrics - Dr. RiniAndyani PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Transfusion Reaction - DRGSPDocument42 pagesTransfusion Reaction - DRGSPGaurav PawarNo ratings yet

- Blood Products & Plasma SubstitutesDocument15 pagesBlood Products & Plasma Substitutesahmadslayman1No ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument18 pagesBlood TransfusionRheimon Jay Abuan BalcitaNo ratings yet

- Crossmatching and Issuing Blood ComponentsDocument20 pagesCrossmatching and Issuing Blood ComponentsMey KhNo ratings yet

- Crossmatching and Issuing Blood Components PDFDocument20 pagesCrossmatching and Issuing Blood Components PDFdianaNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion: Prepared By: Salar N. SulaimanDocument45 pagesBlood Transfusion: Prepared By: Salar N. SulaimanJoanne Bernadette AguilarNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument52 pagesBlood TransfusionAnonymous GC8uMx367% (3)

- Types, Indications and Complications: TransfusionDocument26 pagesTypes, Indications and Complications: TransfusionVatha NaNo ratings yet

- Transfusion Medicine by Dr. Sharad JohriDocument54 pagesTransfusion Medicine by Dr. Sharad JohriShashwat JohriNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion Basic Concepts Blood Transfusion inDocument103 pagesBlood Transfusion Basic Concepts Blood Transfusion iniahmad9No ratings yet

- Additional Review Notes in BBDocument19 pagesAdditional Review Notes in BBKate Danica BumatayNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Unit 2Document6 pagesLaboratory Unit 2Mushy_ayaNo ratings yet

- Transfusion of Blood and Red CellsDocument34 pagesTransfusion of Blood and Red CellsAdams Westlifer SophianoNo ratings yet

- Blood Component TherapyDocument13 pagesBlood Component TherapyMohamed ElgayarNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion ReactionDocument38 pagesBlood Transfusion ReactionMohamed El-sayedNo ratings yet

- PartogramDocument30 pagesPartogramMuwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Examination of Swelling.Document15 pagesExamination of Swelling.Muwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Menopause: by Muzamil OsmanDocument32 pagesMenopause: by Muzamil OsmanMuwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- 3.2 Surgery Paper 3Document13 pages3.2 Surgery Paper 3Muwanga faizo100% (1)

- Rhesus IsoimmunisationDocument27 pagesRhesus IsoimmunisationMuwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- A Must To Revise-1Document19 pagesA Must To Revise-1Muwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Breast Examination: TutorialDocument27 pagesBreast Examination: TutorialMuwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Hernias (Inguinal and Femoral)Document37 pagesHernias (Inguinal and Femoral)Muwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To SurgeryDocument25 pagesIntroduction To SurgeryMuwanga faizo100% (1)

- Git Bleeding - Upper & Lower.Document36 pagesGit Bleeding - Upper & Lower.Muwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- TetanusDocument37 pagesTetanusMuwanga faizoNo ratings yet

- Physiology of BloodDocument97 pagesPhysiology of Bloodbelete psychiatry100% (5)

- Pengaruh Senam Terhadap Penurunan Tekanan Darah Lansia Dengan HipertensiDocument9 pagesPengaruh Senam Terhadap Penurunan Tekanan Darah Lansia Dengan HipertensiVina opinaNo ratings yet

- URINARY SYSTEM - Autonomous ModuleDocument9 pagesURINARY SYSTEM - Autonomous ModulepoonamNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Lymphatic SystemDocument16 pagesUnit 5 Lymphatic SystemChandan ShahNo ratings yet

- Respiratory and Circulatory SystemsDocument4 pagesRespiratory and Circulatory SystemsRommel BauzaNo ratings yet

- Preparation of A 3% Red Cell SuspensionDocument3 pagesPreparation of A 3% Red Cell SuspensionEmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Breathing ExercisesDocument1 pageBreathing ExercisesAbe LinNo ratings yet

- Normal Physical Changes in The ElderlyDocument6 pagesNormal Physical Changes in The Elderlydrng48No ratings yet

- Mechanical AsphyxiaDocument73 pagesMechanical Asphyxiaapi-61200414No ratings yet

- Massive Transfusion ProtocolDocument2 pagesMassive Transfusion ProtocolmukriNo ratings yet

- Science Reviewer For Science Quiz Elementary: MatterDocument30 pagesScience Reviewer For Science Quiz Elementary: MatterGina MontanoNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Science 7Document3 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Science 7atz Kusain100% (1)

- Minipro Anemia Kelompok 1Document62 pagesMinipro Anemia Kelompok 1Vicia GloriaNo ratings yet

- What Is A Blood TransfusionDocument6 pagesWhat Is A Blood TransfusionCarlo TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Blood Drive Host Info PacketDocument5 pagesBlood Drive Host Info PacketMayank MotwaniNo ratings yet

- Treatment and Prognosis of The Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome - UpToDateDocument17 pagesTreatment and Prognosis of The Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome - UpToDateacesacesNo ratings yet

- Science Reviewer Grade 6Document2 pagesScience Reviewer Grade 6Joy VinavilesNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument2 pages1 PBjesonNo ratings yet

- PsyDocument3 pagesPsyvelichkinaanzelikaNo ratings yet

- Complete Blood Picture (CBC) PDFDocument1 pageComplete Blood Picture (CBC) PDFRizwan yousafNo ratings yet

- Menstrual Cycle and SleepDocument2 pagesMenstrual Cycle and Sleepsurajkr07No ratings yet

- Blood Typing LabDocument3 pagesBlood Typing Labapi-279500653No ratings yet

- Diencephalon PhysiologyDocument36 pagesDiencephalon PhysiologyNatnael0% (1)

- Sleep Disorders .KKDocument46 pagesSleep Disorders .KKKhushi KharayatNo ratings yet

- Transportion in Animals and Plants PPT 1Document11 pagesTransportion in Animals and Plants PPT 1Hardik GulatiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19 Blood: Human Anatomy & Physiology, 2e, Global Edition (Amerman)Document22 pagesChapter 19 Blood: Human Anatomy & Physiology, 2e, Global Edition (Amerman)Roman Bereznicki-CommonNo ratings yet

- CronobiologieDocument24 pagesCronobiologiegeorgesculigiaNo ratings yet

- Sleep GuideDocument2 pagesSleep GuideAxel Humberto Franco GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea Case Study: Shirin Shafazand, MD, MS Neomi Shah, MD August 2014Document15 pagesObstructive Sleep Apnea Case Study: Shirin Shafazand, MD, MS Neomi Shah, MD August 2014Vimal NishadNo ratings yet

- Oxygen Advantage Script of ExercisesDocument39 pagesOxygen Advantage Script of ExercisesDimitar Genov92% (12)