Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ch11 Fin202

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Thanh Nhàn K16Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ch11 Fin202

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Thanh Nhàn K16Copyright:

Available Formats

Fundamentals of Corporate Finance

Fifth Edition, International Adaptation

Robert Parrino, Ph.D.; David S. Kidwell, Ph.D.;

Thomas W. Bates, Ph.D.; Stuart Gillan, Ph.D.

Chapter 11

Cash Flows and Capital Budgeting

Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Chapter 11: Cash Flows and Capital

Budgeting

Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2

Learning Objectives

1. Explain why incremental after-tax free cash flows are relevant in

evaluating a project and calculate them for a project

2. Discuss the five general rules for incremental after-tax free cash flow

calculations and explain why cash flows stated in nominal (real)

dollars should be discounted using a nominal (real) discount rate

3. Describe how distinguishing between variable and fixed costs can be

useful in forecasting operating expenses

4. Explain the concept of equivalent annual cost and use it to compare

projects with unequal lives, decide when to replace an existing asset,

and calculate the opportunity cost of using an existing asset

5. Determine the appropriate time to harvest an asset

Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3

11.1 Calculating Project Cash Flows

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain why incremental after-tax free cash flows are relevant in

evaluating a project and calculate them for a project

• Incremental after-tax free cash flows

• The FCF calculation

• Cash flows from operations

• Cash flows associated with capital expenditures and

net working capital

• The FCF calculation: An example

• FCF versus accounting earnings

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 4

Calculating Project Cash Flows

• Cash flows and profit

o To provide adequate net cash flow, the average selling price of a

unit should not be less than the sum of the cost of making the unit,

the fixed cost (overhead) for the unit, and an adequate return (in

$) for the unit

• Capital budgeting involves estimating the NPV of the cash

flows a project is expected to produce in the future

o All of the cash flow estimates are forward-looking rather than

historical accounting information

o Cash flows that have already occurred or will occur regardless of

the outcome of the capital budgeting decision are not considered

(sunk costs)

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 5

Incremental After-Tax Free Cash

Flows

• Only incremental after-tax cash flow is used in an NPV

analysis; this is the amount of additional unrestricted free

cash flow (FCF) a firm will have if the project is adopted

Free cash flow is cash remaining after a firm has made

o

necessary project-related expenditures for working capital

and long-term assets

o FCF is cash a firm can distribute to creditors and

stockholders

Equation 11.1

FCFProject FCFFirm with project FCFFirm without project

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 6

Exhibit 11.1: The Free Cash Flow

Calculation for a Project

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 7

The FCF Calculation

Equation 11.2

FCF=[(Revenue − Op Ex − D&A) × (1 − t)] + D&A − Cap

Exp − Add WC

Where:

Op Ex is operating expenses

D&A is depreciation and amortization

Cap Exp is capital expenditures

Add WC is additional working capital

t is the tax rate

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 8

Example: FCF Calculation

• A new truck will increase revenues by $50,000 and

operating expenses by $30,000 per year. It will be

depreciated over 3 years at $10,000 per year. Your firm’s

marginal tax rate is 25%. Capital expenditures will be

$3,000 annually but no additional working capital will be

needed. Calculate the yearly free cash flow.

Using Equation 11.2

FCF = $50, 000 $30, 000 $10, 000 1 0.25

$10, 000 $3, 000 $0

$14,500

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 9

The Stand-Alone Principle

• The “stand-alone principle” is the idea that cash flows

from a project can be evaluated independently of a

firm’s other cash flows

o It treats each project as a separate firm with its own

revenue, expenses, and investment requirements

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10

Cash Flows from Operations (1 of 2)

• The incremental cash flow from operations, CF Opns,

equals the incremental net operating profits after tax

(NOPAT) plus the depreciation and amortization

(D&A) associated with the project

o The firm’s marginal tax rate (t) is used to calculate

NOPAT because net cash flows from a new project are

assumed to be incremental to the firm

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 11

Steps in Calculating Cash Flows from

Operations (1 of 2)

• Compute the project’s incremental cash flow from

operations (CFOpns) which equals the incremental net

operating profits after tax (NOPAT) plus D&A. This is

cash flow remaining after operating expenses and taxes

have been paid

• Subtract expenditures for the project’s capital assets

(Cap Exp) and extra working capital (Add WC)

• FCF is a project’s after-tax cash flow over and above

what is necessary for project-related expenditures

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 12

Steps in Calculating Cash Flows from

Operations (2 of 2)

• Depreciation and amortization (D&A) associated with

the project are added to NOPAT when calculating

CFOpns

• D&A expense is deducted for calculating taxable

income, but no cash outflow is involved, so it is added

to NOPAT to determine the cash flow from operations

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 13

Cash Flows Associated with Capital

Expenditures and Net Working Capital (1 of

2)

• Investments needed to fund additions to working

capital

o Inventory

o Accounts receivable

• Investments required to purchase long-term tangible

assets

o Plant

o Equipment

o Licenses

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 14

Exhibit 11.2 FCF Calculation Worksheet

for the Performing Arts Center Project

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 15

Exhibit 11.3: Completed FCF

Calculation Worksheet for the

Performing Arts Center Project

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 16

FCF versus Accounting Earnings

• A project’s impact on a firm’s value and stock price does not

depend on how the project affects accounting earnings; it

depends on how the project affects free cash flows

• Accounting earnings may differ from cash flows for a number

of reasons, making accounting earnings an unreliable measure

of the costs and benefits of a project

o Accounting earnings are reduced by non-cash charges, such as

depreciation and amortization

o These charges account for the deterioration of a business’ long-

term assets, but do not involve a cash outlay at the time the

expense is incurred

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 17

Using Excel: Performing Arts Center

Project

L.O. 11.1 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 18

11.2 Estimating Cash Flows in Practice

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Discuss the five general rules for incremental after-tax free cash

flow calculations and explain why cash flows stated in nominal

(real) dollars should be discounted using nominal (real) discount

rate

• Five General Rules for Incremental After-Tax Free

Cash Flow Calculations

• Nominal versus Real Cash Flows

• Tax Rates and Depreciation

• Computing the Terminal-Year FCF

• Expected Cash Flows

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 19

Five General Rules for Incremental After-

Tax Free Cash Flow Calculations (1 of 2)

1) Include cash flows only

o Do not include allocated costs or overhead unless they occur

because of the project

2) Include the impact of the project on cash flows of other

product lines

o If a project is expected to affect cash flows of another

project, include the expected impact on the cash flows of the

other project in the analysis

3) Include all opportunity costs

o Benefits that could have been earned by choosing another

project are a cost to the firm

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 20

Five General Rules for Incremental After-

Tax Free Cash Flow Calculations (2 of 2)

4) Forget sunk costs

o Sunk costs have already been incurred or committed to and

will not be influenced by the project

5) Include only after-tax cash flows

o Incremental pre-tax cash flow earnings of a project only

matter to the extent that they determine the free after-tax

cash flows

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 21

Exhibit 11.4: Adjusted FCF

Calculations and NPV for the

Performing Arts Center Project

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 22

Nominal versus Real Cash Flows

• Nominal dollars represent the actual dollar amounts that we

expect a project to generate in the future, without any

adjustments for purchasing power

o When prices increase, a given nominal dollar amount will

buy less than before

• Real dollars represent dollars stated in terms of constant

purchasing power

• Constant purchasing power is in terms of prices that

existed in an earlier period

o Constant purchasing power: “Last year this cost $50. Today

it costs $60.” The price increased by 20%; in real terms, $60

today has the buying power of $50 a year ago

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 23

The Cost of Capital

• The cost of capital, k, can be written as:

Equation 11.3

1 k 1 Pe 1 r

k 1 Pe 1 r 1

Where:

k is the nominal cost of capital

∆Pe is the expected rate of inflation

r is the real cost of capital

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 24

Project Cash Flows

• Project cash flows should be stated either in nominal

dollars or in real dollars

o Value nominal cash flows using a nominal interest rate

o Value real cash flows using a real interest rate

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 25

Example: Nominal versus Real Cash

Flows (1 of 4)

• A project requires an initial investment of $50,000 and will

produce FCFs of $20,000 for four years. At a 15% nominal

cost of capital, the NPV of the project is:

$20, 000 $20, 000 $20, 000 $20, 000

NPV = $50,000+

1.15 1.15 1.15 1.15

1 2 3 4

= $50, 000 $17,391.30 $15,122.87 $13,150.32 $11, 435.06

= $7, 099.55

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 26

Example: Nominal vs. Real Cash

Flows (2 of 4)

• The real cost of capital for the project when the

expected rate of inflation is 5%:

1 k 1.15

r 1 1 0.09524, or 9.52%

1 Pe 1.05

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 27

Example: Nominal vs. Real Cash

Flows (3 of 4)

• Real cash flows for the project

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4

$50, 000 $20, 000 $20, 000 $20, 000 $20, 000

1 0.05 1 0.05 1 0.05 1 0.05

2 3 4

$50, 000 $19, 048 $18,141 $17, 277 $16, 454

$19, 048 $18,141 $17, 277 $16, 454

NPV $50,000+

1.09524 1.09524 1.09524 1.09524

1 2 3 4

$50, 000 $17,391 $15,123 $13,150 $11, 435

$7, 099

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 28

Example: Nominal vs. Real Cash

Flows (4 of 4)

• NPV for the project is the same for both calculations

o It is the same because the nominal rate of 15% includes the

adjustment for the 5% expected inflation

o If the nominal rate was 14% when the expected rate of

inflation was 5%, the project would be overvalued

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 29

Tax Rates and Depreciation

• The progressive or marginal tax system used in the United

States is one in which the proportion of income paid as taxes

increases as the amount of taxable income increases

• Corporations keep two sets of books because the GAAP rules

for computing income are different from the rules that the IRS

uses

o One set is kept for preparing financial statements in accordance

with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and filed

with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

o The other set is kept for computing the taxes that the corporation

actually pays

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 30

Marginal and Average Tax Rates

• The average tax rate is the total taxes paid divided by

taxable income

• In contrast, the marginal tax rate is the tax rate that is

paid on the last dollar of income earned

• When you are making investment decisions, the

relevant tax rate to use is usually the marginal tax rate.

The reason is that new investments (projects) are

expected to generate new cash flows, which will be

taxed at the business’s marginal tax rate.

• As a result, the marginal tax rate is the relevant rate for

financial decision making

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 31

Taxes and Depreciation

• One especially important difference from a capital budgeting

perspective is that the depreciation methods allowed by GAAP

differ from those allowed by the IRS

• The straight-line depreciation method illustrated earlier in this

chapter in the Performing Arts Center example is allowed by

GAAP and is often used for financial reporting

• In contrast, the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System

(MACRS), has been acceptable for depreciation in U.S. federal

tax calculations since the Tax Reform Act of 1986

o MACRS allows a firm to allocate more of the depreciation

expense to the early years of a project, realizing larger tax savings

sooner, and increasing the present value of the tax shield

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 32

Exhibit 11.5: MACRS Depreciation

Schedules by Allowable Recovery Period

(1 of 2)

Year 3-Year 5-Year 7-Year 10-Year 15-Year 20-Year

1 33.33% 20.00% 14.29% 10.00% 5.00% 3.75%

2 44.45 32.00 24.49 18.00 9.50 7.22

3 14.81 19.20 17.49 14.40 8.55 6.68

4 7.41 11.52 12.49 11.52 7.70 6.18

5 5.76 8.93 9.22 6.93 5.71

6 8.92 7.37 6.23 5.29

7 8.93 6.55 5.90 4.89

8 4.46 6.56 5.90 4.52

9 6.55 5.91 4.46

10 3.28 5.90 4.46

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 33

Exhibit 11.5: MACRS Depreciation

Schedules by Allowable Recovery Period

(2 of 2)

Year 3-Year 5-Year 7-Year 10-Year 15-Year 20-Year

11 5.91 4.46

12 5.90 4.46

13 5.91 4.46

14 5.90 4.46

15 5.91 4.46

16 2.95 4.46

17 4.46

18 4.46

19 4.46

20 4.46

21 2.24

Total 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00% 100.00%

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 34

Computing Terminal-Year FCF

• FCF in the last, or terminal, year of a project often includes cash

flows not typically included in the calculations for prior years

o Long-term assets and working capital that are no longer needed to

support the project may be sold and funds used in other ways

o Net cash flows from the sale of assets and the impact of the sale

on the firm’s taxes are included in the terminal-year FCF

Equation 11.4

Add WC = Change in cash and cash equivalents

+ Change in accounts receivable

+ Change in inventories

– Change in accounts payable

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 35

MACRS Depreciation Calculations

for the Performing Arts Center

Project ($ thousands)

Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 10

Depreciation Calculations

Beginning book value $10,000 $9,000 $7,200 $5,760 $4,608 $3,686 $2,949 $2,294 $1,639 $983

MACRS percentage 10.00% 18.00% 14.40% 11.52% 9.22% 7.37% 6.55% 6.55% 6.56% 6.55%

MACRS depreciation $1,000 $1,800 $1,440 $1,152 $922 $737 $655 $655 $656 $655

Ending book value $9,000 $7,200 $5,760 $4,608 $3,686 $2,949 $2,294 $1,639 $983 $328

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 36

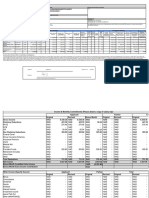

Exhibit 11.7: FCF Calculations and

NPV for Performing Arts Center

Project with MACRS Depreciation ($

thousands)

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 10

Revenue $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100 $14,100

−Op Ex 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460 8,460

EBITDA $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460 $5,460

−D&A 1,000 1,800 1,440 1,152 922 737 655 655 656 655

EBIT $4,640 $3,840 $4,200 $4,488 $4,718 $4,903 $4,985 $4,985 4,984 $4,985

× (1 − t) 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70 0.70

NOPAT $3,248 $2,688 $2,940 $3,142 $3,303 $3,432 $3,490 $3,490 $3,489 $3,490

+D&A 1,000 1,800 1,440 1,152 922 737 655 655 656 655

CF Opns $4,248 $4,488 $4,380 $4,294 $4,225 $4,169 $4,145 $4,145 $4,145 $4,145

−Cap Exp $10,000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 −98

−Add WC 1,000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 −1,000

=FCF −$11,000 $4,248 $4,488 $4,380 $4,294 $4,225 $4,169 $4,145 $4,145 $4,145 $5,243

NPV @ 10% $15,610

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 37

FCF Calculations and NPV for the

Performing Arts Center Project with a

$1 Million Salvage Value in Year 10 ($ thousands)

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6 Year 7 Year 8 Year 9 Year 10

CF Opns $4,248 $4,488 $4,380 $4,294 $4,225 $4,169 $4,145 $4,145 $4,145 $4,145

−Cap Exp $10,000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 −798

−Add WC 1,000 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 −1,000

=FCF −$11,000 $4,248 $4,488 $4,380 $4,294 $4,225 $4,169 $4,145 $4,145 $4,145 $5,943

NPV @ 10% $15,880

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 38

Expected Cash Flows

• It is important to realize that an NPV analysis uses the

“expected” FCF for each year of the life of a project

o Expected means estimated

• Each FCF is a weighted average of the possible cash

flows from each possible future outcome

o The possible cash flow from each outcome is weighted

by the probability that the outcome will occur

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 39

Expected FCFs for New Board Game

($ thousands)

Outcome Probability Year: 0 Year: 1 Year: 2 Year: 3

Game sales are excellent 0.25 −$100.00 $70.00 $90.00 $60.00

Game sales are good 0.50 −100.00 50.00 55.00 40.00

Game sales are poor 0.25 −100.00 25.00 15.00 0.00

Expected FCF −$100.00 $48.75 $53.75 $35.00

L.O. 11.2 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 40

11.3 Forecasting Free Cash Flows

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe how distinguishing between variable and fixed costs

can be useful in forecasting operating expenses

• Cash flows from operations

• Cash flows associated with capital expenditures and

net working capital

L.O. 11.3 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 41

Cash Flows from Operations (2 of 2)

• To forecast incremental cash flows from operations, you

need to forecast the incremental net revenue, operating

expenses, depreciation, and amortization

• Analysts often distinguish between types of costs when

forecasting operating expenses

o Fixed costs that do not change with the units of output

o Variable costs that change with every unit of output

L.O. 11.3 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 42

Cash Flows Associated with Capital

Expenditures and Net Working Capital (2 of

2)

• Capital expenditure forecasts reflect the expected level of

investment during each year of a project’s life, including

inflows from salvage value and tax costs or benefits

associated with asset sales

• Net working capital included in the cash flow forecasts of

an NPV analysis are

o Cash and cash equivalents

o Accounts receivable

o Inventories

o Accounts payable

L.O. 11.3 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 43

11.4 Special Cases

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Explain the concept of equivalent annual cost and use it to

compare projects with unequal lives, decide when to replace an

existing asset, and calculate the opportunity cost of using an

existing asset

• Projects with different lives

• When to replace an existing asset

• The cost of using an existing asset

L.O. 11.4 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 44

Projects with Different Lives

• An efficient method of choosing between mutually exclusive

projects with different lives is to compute their equivalent

annual cost:

Equation 11.5

1 k t

EACi kNPVi

1 k 1

t

• Where :

k is the opportunity cost of capital

NPVi is normal NPV of project I

t is the lifespan of the project.

L.O. 11.4 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 45

Example: Projects with Different

Lives

Find the EAC of two projects: mower A, which costs $250 and is

expected to last two years, and mower B, which costs $360 and is

expected to last three years. The cost of capital is 10%.

1.10 2

EACA 0.1 $250 $144.05

1.10 1

2

1.10 3

EAC B 0.1 $360 $144.76

1.10 1

3

L.O. 11.4 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 46

When to Replace an Existing Asset

• Determining whether to replace an old, but still useful

asset with a new one is a common problem

o Compute the EAC for the new asset and compare it to

the annual cash inflows from the old asset; choose the

one with the higher equivalent cash flow

L.O. 11.4 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 47

The Cost of Using an Existing Asset

• The Cost of Using an Existing Asset

o When calculating incremental after-tax cash flows,

include opportunity costs that may not be directly

observable, for example when the opportunity cost

relates to the use of excess capacity associated with an

existing asset

o Sometimes incremental cash flows have to be computed

by using the EAC for a given set of cash flows, then

adjusting the EAC by the appropriate discount rate and

time if the EAC is not in present-value form

L.O. 11.4 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 48

11.5 Harvesting an Asset

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Determine the appropriate time to harvest an asset

• Harvesting an Asset

L.O. 11.5 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 49

When to Harvest an Asset

• Some investments experience a rapid increase in

nominal NPV early in the project, and later the rate of

increase declines

o The optimal time to harvest or cash-in these

investments is when the rate of increase in an asset’s

nominal NPV equals the opportunity cost of capital

o At this point, liquidate the asset and invest the proceeds

in alternatives that yield more than the opportunity cost

of capital

L.O. 11.5 Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 50

Copyright

Copyright © 2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

All rights reserved. Reproduction or translation of this work beyond that permitted in

Section 117 of the 1976 United States Act without the express written permission of the

copyright owner is unlawful. Request for further information should be addressed to the

Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The purchaser may make back-up

copies for his/her own use only and not for distribution or resale. The Publisher assumes

no responsibility for errors, omissions, or damages, caused by the use of these programs or

from the use of the information contained herein.

Copyright ©2022 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 51

You might also like

- CH 11Document51 pagesCH 11Naresh HariyaniNo ratings yet

- ch10 Fin202Document68 pagesch10 Fin202Nguyễn Thanh Nhàn K16No ratings yet

- CH 11Document63 pagesCH 11Duc Tai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Lecture 11Document62 pagesLecture 11lilyblooms.atlasNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five & SixDocument58 pagesChapter Five & SixmengistuNo ratings yet

- Capital BudgetingDocument24 pagesCapital BudgetingHassaan NasirNo ratings yet

- Situation 1Document80 pagesSituation 1Junaid RazzaqNo ratings yet

- Financial Anaysis of ProjectDocument48 pagesFinancial Anaysis of ProjectalemayehuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document34 pagesChapter 13Aryan JainNo ratings yet

- Final Project Cash FlowsDocument25 pagesFinal Project Cash FlowsLalit Sondhi100% (1)

- Ch11 RevisedDocument33 pagesCh11 RevisedNhân TrầnNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow EstimationDocument35 pagesCash Flow EstimationAtheer Al-AnsariNo ratings yet

- Gitman pmf13 ppt11Document53 pagesGitman pmf13 ppt11Sajjad AhmadNo ratings yet

- 3.a Capital Budgeting AnalysisDocument81 pages3.a Capital Budgeting AnalysisMegha SenNo ratings yet

- Ch11 - Capital Budgeting Cash Flows (G)Document30 pagesCh11 - Capital Budgeting Cash Flows (G)NerissaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-4 (Capital Budgeting)Document26 pagesChapter-4 (Capital Budgeting)Milad AkbariNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting CashDocument95 pagesCapital Budgeting CashSetya BudiNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting - FIN 072 (Final)Document47 pagesCapital Budgeting - FIN 072 (Final)Dale JimenoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 Project Cash FlowsDocument28 pagesChapter 9 Project Cash FlowsGovinda AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Investment Valuation Criteria: Lecture 9thDocument49 pagesInvestment Valuation Criteria: Lecture 9thMihai StoicaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 9 InvestmentDocument34 pagesLecture 9 InvestmentCristina IonescuNo ratings yet

- Session 10 Chapter 10 Making Capital InvestmentDecisionDocument35 pagesSession 10 Chapter 10 Making Capital InvestmentDecisionLili YaniNo ratings yet

- CH 10Document72 pagesCH 10Utsav DubeyNo ratings yet

- Chapter Ten: Making Capital Investment DecisionDocument34 pagesChapter Ten: Making Capital Investment DecisionRehman LaljiNo ratings yet

- Rate of Return of An InvestmentDocument49 pagesRate of Return of An InvestmentAllya CaveryNo ratings yet

- FM Unit 8 Lecture Notes - Capital BudgetingDocument4 pagesFM Unit 8 Lecture Notes - Capital BudgetingDebbie DebzNo ratings yet

- Finch 11713Document166 pagesFinch 11713Ali ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- CASH FLOW ESTIMATION Week 6Document30 pagesCASH FLOW ESTIMATION Week 6adulmi325No ratings yet

- Lecture 8Document28 pagesLecture 8Hồng LêNo ratings yet

- Ross Fundamentals of Corporate Finance 13e CH10 PPT AccessibleDocument38 pagesRoss Fundamentals of Corporate Finance 13e CH10 PPT AccessibleAdriana RisiNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow Estimation and Capital BudgetingDocument29 pagesCash Flow Estimation and Capital BudgetingShehroz Saleem QureshiNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting Cash FlowsDocument54 pagesCapital Budgeting Cash Flowssita deliyana FirmialyNo ratings yet

- V - Project Evaluation - 2022Document42 pagesV - Project Evaluation - 2022A373728272No ratings yet

- MGMT2023 Lecture 8 - Capital Budgeting Part 1Document44 pagesMGMT2023 Lecture 8 - Capital Budgeting Part 1Ismadth2918388No ratings yet

- 10.cap+budgeting Cash Flows-1Document20 pages10.cap+budgeting Cash Flows-1Navid GodilNo ratings yet

- CF Chapter 2 NotesDocument17 pagesCF Chapter 2 NotessdfghjkNo ratings yet

- CH 11Document48 pagesCH 11Pham Khanh Duy (K16HL)No ratings yet

- Alternatives To PV & Corporate Finale: Pete HahnDocument39 pagesAlternatives To PV & Corporate Finale: Pete HahnpartyycrasherNo ratings yet

- International Capital BudgetingDocument43 pagesInternational Capital BudgetingRammohanreddy RajidiNo ratings yet

- 254 Chapter 10Document23 pages254 Chapter 10Zidan ZaifNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - Capital Budgeting Cash Flows PDFDocument32 pagesChapter 11 - Capital Budgeting Cash Flows PDFMaisha Tanzim RahmanNo ratings yet

- Part Iv: Capital Budgeting: 4.2. Estimation of Project Cash FlowsDocument46 pagesPart Iv: Capital Budgeting: 4.2. Estimation of Project Cash FlowsShivani JoshiNo ratings yet

- M12 Titman 2544318 11 FinMgt C12Document80 pagesM12 Titman 2544318 11 FinMgt C12marjsbarsNo ratings yet

- Gitman Capital BudgetingDocument51 pagesGitman Capital BudgetingjaneNo ratings yet

- Gitman 7 Stock ValuationDocument51 pagesGitman 7 Stock Valuationm0987ahNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word Document (3) (Recovered)Document7 pagesNew Microsoft Word Document (3) (Recovered)Tazeem OmerNo ratings yet

- Hongkong Capital BudgetDocument77 pagesHongkong Capital BudgetZoloft Zithromax ProzacNo ratings yet

- Ebook Corporate Finance 1St Edition Booth Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument42 pagesEbook Corporate Finance 1St Edition Booth Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFpaullanb7nch100% (9)

- Week 10 - 11 - Investment Appraisal TechniquesDocument15 pagesWeek 10 - 11 - Investment Appraisal TechniquesJoshua NemiNo ratings yet

- Capital Investment DecisionDocument16 pagesCapital Investment DecisionAbraham LinkonNo ratings yet

- 1 - Topic1CashFlowEstimations-EditedDocument34 pages1 - Topic1CashFlowEstimations-EditedCOCONUTNo ratings yet

- Net Present Value and Other Investment Criteria: Principles of Corporate FinanceDocument36 pagesNet Present Value and Other Investment Criteria: Principles of Corporate FinanceSAKSHI SHARMANo ratings yet

- Lecture 6-Capital Budgeting - Project Analysis & EvaluationDocument57 pagesLecture 6-Capital Budgeting - Project Analysis & EvaluationSour CandyNo ratings yet

- Estimation of Cash FlowsDocument31 pagesEstimation of Cash FlowsAyman SobhyNo ratings yet

- Strategic Investment Decisions: Measuring, Monitoring, and Motivating PerformanceDocument36 pagesStrategic Investment Decisions: Measuring, Monitoring, and Motivating Performancechitu1992No ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting NotesDocument11 pagesCapital Budgeting NotesAmyNo ratings yet

- Capital BudgetingDocument34 pagesCapital BudgetingvijayluckeyNo ratings yet

- Applied Corporate Finance. What is a Company worth?From EverandApplied Corporate Finance. What is a Company worth?Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Decoding DCF: A Beginner's Guide to Discounted Cash Flow AnalysisFrom EverandDecoding DCF: A Beginner's Guide to Discounted Cash Flow AnalysisNo ratings yet

- FMN11B1 Unit 2 (Part 1 - Chapter 2) Slides - 2023Document28 pagesFMN11B1 Unit 2 (Part 1 - Chapter 2) Slides - 2023Takudzwa MutirikidiNo ratings yet

- Seminar 6.1Document2 pagesSeminar 6.1Đạt PhạmNo ratings yet

- Financial RatioDocument2 pagesFinancial RatioNurul NajihahNo ratings yet

- International Financial Management Canadian Perspectives 2Nd Edition Eun Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument33 pagesInternational Financial Management Canadian Perspectives 2Nd Edition Eun Test Bank Full Chapter PDFPatriciaSimonrdio100% (10)

- Chapter 4 - Income From Other SourcesDocument23 pagesChapter 4 - Income From Other SourcesPuran GuptaNo ratings yet

- Portfolio 3Document27 pagesPortfolio 3nehalefatNo ratings yet

- TIH Financial Freedom EbookDocument15 pagesTIH Financial Freedom EbookRajeev Kumar PandeyNo ratings yet

- Understanding Canadian Business Canadian 8th Edition Nickels Solutions Manual DownloadDocument26 pagesUnderstanding Canadian Business Canadian 8th Edition Nickels Solutions Manual DownloadChad Powell100% (21)

- Intermediate Accounting Chapter 7 Exercises - ValixDocument26 pagesIntermediate Accounting Chapter 7 Exercises - ValixAbbie ProfugoNo ratings yet

- Refinement of The Ecb Guide To Internal ModelsDocument16 pagesRefinement of The Ecb Guide To Internal ModelsjayaNo ratings yet

- Group 2Document26 pagesGroup 2Hyunjin imtreeeNo ratings yet

- Products. Goods and Services - CR CabatinDocument38 pagesProducts. Goods and Services - CR CabatinRogel CabatinNo ratings yet

- HDFCDocument12 pagesHDFCsai123vinay111No ratings yet

- Presentation On Adidas and Its Branding ProcessDocument16 pagesPresentation On Adidas and Its Branding ProcessTalha LatifNo ratings yet

- AC4301 FinalExam 2020-21 SemA AnsDocument9 pagesAC4301 FinalExam 2020-21 SemA AnslawlokyiNo ratings yet

- Creditor Proposal - (Overall) New Template1Document74 pagesCreditor Proposal - (Overall) New Template1LineekelaNo ratings yet

- Monopolistic Competition - MaterialsDocument12 pagesMonopolistic Competition - Materialsroshxsam1972No ratings yet

- Bánh Ta ReportDocument34 pagesBánh Ta Reportduyenhtnbds160037No ratings yet

- Practica Modulo 6 EnunciadosDocument3 pagesPractica Modulo 6 EnunciadosJulian Brescia2No ratings yet

- Marketing Mix of Coca-ColaDocument9 pagesMarketing Mix of Coca-ColaMiskatul JannatNo ratings yet

- MKT 501 - Group 3 - Mini Assignment - Holistic Marketing - ACI LimitedDocument8 pagesMKT 501 - Group 3 - Mini Assignment - Holistic Marketing - ACI LimitedMd. Rafsan Jany (223052005)No ratings yet

- Company ProfileDocument6 pagesCompany ProfileAnna CatherineNo ratings yet

- Group 8 Verkkokauppa - Com Business AnalysisDocument20 pagesGroup 8 Verkkokauppa - Com Business AnalysisnujhatpromyNo ratings yet

- Homework 10Document1 pageHomework 10Maido TeNo ratings yet

- MBDocument5 pagesMBShatakshi ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Commercial Banks, FI and NBIFDocument17 pagesCommercial Banks, FI and NBIFVikash kumarNo ratings yet

- Bollinger Bands Strategy With 20 Period Trading SystemDocument10 pagesBollinger Bands Strategy With 20 Period Trading SystemOPTIONS TRADING20No ratings yet

- NEM0XX EBOOK 2023 - MalaysianSNR - FREE - CompressedDocument24 pagesNEM0XX EBOOK 2023 - MalaysianSNR - FREE - CompressedDaniel Zua100% (2)

- Answers To Problem Sets: How Corporations Issue SecuritiesDocument10 pagesAnswers To Problem Sets: How Corporations Issue Securitiesmandy YiuNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Case Study-Big Bazaar DirectDocument15 pagesAnalysis of Case Study-Big Bazaar DirectProtanu GhoshNo ratings yet