Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Exam, Diagno & Treat. of Perio Diseases

Uploaded by

Kekelwa Mutumwenu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views65 pagesThis document provides information on the examination, clinical diagnosis, and treatment of periodontal diseases. It discusses the importance of a thorough evaluation including medical and dental history, clinical and radiographic exams, photographs, and casts. A proper diagnosis requires determining if disease is present, identifying its type, extent, and severity by analyzing case history, clinical signs/symptoms, and test results. Diagnoses include gingivitis, various forms of periodontitis, and oral manifestations of systemic diseases. The sequence of a full periodontal exam over two visits is described in detail.

Original Description:

Exam

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document provides information on the examination, clinical diagnosis, and treatment of periodontal diseases. It discusses the importance of a thorough evaluation including medical and dental history, clinical and radiographic exams, photographs, and casts. A proper diagnosis requires determining if disease is present, identifying its type, extent, and severity by analyzing case history, clinical signs/symptoms, and test results. Diagnoses include gingivitis, various forms of periodontitis, and oral manifestations of systemic diseases. The sequence of a full periodontal exam over two visits is described in detail.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

4 views65 pagesExam, Diagno & Treat. of Perio Diseases

Uploaded by

Kekelwa MutumwenuThis document provides information on the examination, clinical diagnosis, and treatment of periodontal diseases. It discusses the importance of a thorough evaluation including medical and dental history, clinical and radiographic exams, photographs, and casts. A proper diagnosis requires determining if disease is present, identifying its type, extent, and severity by analyzing case history, clinical signs/symptoms, and test results. Diagnoses include gingivitis, various forms of periodontitis, and oral manifestations of systemic diseases. The sequence of a full periodontal exam over two visits is described in detail.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 65

Examination, Clinical Diagnosis

And Treatment Of Perio Diseases

Introduction

• Periodontal treatment requires an

interrelationship

between the care of the periodontium and other

phases of dentistry.

• The concept of total treatment is based on the

elimination of gingival inflammation and the

factors that lead to it.

• Factors related to gingival inflammation

– 1.plaque accumulation that favored by calculus

and pocket formation

– 2. inadequate restorations, and

– 3. areas of food impaction.

• Total treatment requires consideration of

systemic aspects, including the possibility of

interaction of periodontal disease with other

diseases.

• Systemic adjuncts to local treatment, and special

precautions in patient management is important.

• It may also entail consideration of functional

aspects for the establishment of optimal occlusal

relationships for the entire dentition.

• A rational sequence of dental procedures

that includes periodontal and other measures

necessary to create a well-functioning

dentition in a healthy periodontal

environment should be followed.

Clinical Diagnosis

FIRST VISIT

• Overall Appraisal of the Patient

• Medical History

• Dental History

• Intraoral Radiographic Survey

• Casts

• Clinical Photographs

• Review of the Initial Examination

SECOND VISIT

• Oral Examination

• Examination of the Teeth

• Examination of the Periodontium

• THE PERIODONTAL SCREENING AND RECORDING

SYSTEM

• LABORATORY AIDS TO CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

– Nutritional Status

– Patients on Special Diets for Medical Reasons

– Blood Tests

Diagnosis of Periodontal Conditions

• Proper diagnosis is essential to intelligent

treatment.

• Periodontal diagnosis should first determine

– whether disease is present

– then identify its type

– extent,

– distribution,

– and severity;

– an understanding of the underlying pathologic

processes and its cause.

In general, periodontal diagnoses fall into three

broad categories.

– The gingival diseases

– The various types of periodontitis

– The periodontal manifestations of systemic

diseases

Gingival diseases

• Periodontal diagnosis is determined after

– careful analysis of the case history

– evaluation of the clinical signs and symptoms

– Evaluation of the results of various tests (e.g.,

probing mobility assessment, radiographs, blood

tests, and biopsies)

• The interest should be in the patient who has

the disease and not simply in the disease

itself.

• Diagnosis must therefore include a general

evaluation of the patient and consideration of the

oral cavity.

• Diagnostic procedures must be systematic and

organized for specific purposes. It is not enough

to only assemble facts.

• The findings must be pieced together so that they

provide a meaningful explanation of the patient's

periodontal problem.

Recommended sequence of procedures for

the diagnosis of periodontal diseases.

FIRST VISIT

• Overall Appraisal of the Patient

– From the first meeting, the clinician should

attempt an overall appraisal of the patient.

– This includes consideration of the patient's

mental and emotional status,

temperament ,attitude, and physiologic age.

Medical History

• Most medical history is obtained in first visit

and can be supplemented by pertinent

questioning at subsequent visits.

• The health history can be obtained verbally by

questioning the patient and recording his or

her responses on a blank piece of paper or by

means of a printed questionnaire the patient

complétés.

• The patient should be made aware of

(1) the possible role that some systemic

diseases, conditions or behavioral factors may

play in the cause of periodontal disease

(2) oral infection may have a powerful

influence on the occurrence and severity of a

variety of systemic diseases and conditions.

• The medical history aids the clinician in

– the diagnosis of oral manifestations of systemic

disease

– detection of systemic conditions that may be

affecting the periodontal tissue response to local

factors

– Detection of systemic conditions that require

special precautions and/or modifications in

treatment procedures.

The medical history should include reference to:

1. Is the patient under the care of a physician and, if so,

what is the nature and duration of the problem and

the therapy? The name, address, and telephone number of the

physician should be recorded, since direct communication with

him or her may be necessary.

2. Details on hospitalization and operations, including

diagnosis, kind of operation, and untoward events

such as anesthetic, hemorrhagic, or infectious complications,

should be provided.

3. A list should be supplied of all medications being

taken and whether they were prescribed or obtained over

the counter.

- possible effects of these medications should be carefully

analyzed to determine their effect, if any, on the oral

tissues

- also to avoid administering medications that would

interact adversely with them.

- Special inquiry should be made regarding the dosage

and duration of therapy with anticoagulants and

corticosteroids.

4. History should be taken of all medical

problems (cardiovascular, hematologic,

endocrine, etc.), including infectious diseases,

sexually transmitted diseases, and high-risk

behavior for human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) infection.

5. Any possibility of occupational disease should

be noted

6. Abnormal bleeding tendencies such as nosebleeds,

prolonged bleeding from minor cuts, spontaneous

ecchymoses, tendency toward excessive bruising, and

excessive menstrual bleeding should be cited.

7. History of allergy should be taken, including hay

fever, asthma, sensitivity to foods, or sensitivity to

drugs such as aspirin, codeine, barbiturates,

sulfonamides, antibiotics, procaine, and laxatives, to

dental materials such as eugenol or acrylic resins.

8. Information is needed regarding the onset of

puberty for females, menopause, menstrual

disorders, hysterectomy, pregnancies, and

miscarriages.

9. Family medical history should be taken,

including bleeding disorders and diabetes

Dental History

Include

• list of visits to the dentist including frequency; date of the most

recent visit; nature of the treatment; and oral prophylaxis or

cleaning by a dentist or hygienist, including frequency and date of

most recent cleaning.

• The patient's oral hygiene regimen should be noted, including

tooth brushing frequency, time of day, method, type of toothbrush

and dentifrice, and interval at which brushes are replaced.

• Other methods for mouth care, such as mouthwashes, finger

massage, interdental stimulation, water irrigation, and dental floss.

• What are the patient's general dental habits?

– If there is any grinding or clenching of the teeth during the

day or at night.

– Do the teeth or jaw muscles feel "sore" in the morning?

– Are there other habits, such as tobacco smoking or chewing,

nail biting, or biting on foreign objects?

• History of previous periodontal problems should be

noted, including the nature of the condition and, if

previously treated, the type of treatment received

(surgical or nonsurgical) and approximate period of

termination of previous treatment.

• If, in the opinion of the patient, the present

problem is a recurrence of previous disease,

what does he or she think caused it?

Intraoral Radiographic Survey

• The radiographic survey should consist of a

minimum of 14 intraoral films and four posterior

bite-wing films

• Panoramic radiographs are a simple and convenient

method of obtaining a survey view of the dental

arch and surrounding structures

• They are helpful for the detection of developmental

anomalies, pathologic

lesions of the teeth and jaws, and fractures as well

as dental screening examinations of large groups.

• They provide an informative overall

radiographic picture of the distribution and

severity of bone destruction in periodontal

disease, but a complete intraoral series is

required for periodontal diagnosis and

treatment planning. .

Casts

• Casts from dental impressions are extremely useful adjuncts in

the oral examination.

• They indicate the position of the gingival margins and the

position and inclination of the teeth, proximal contact

relationships, and food impaction areas. In addition, they

provide a view of lingual-cuspal relationships.

• They are important records of the dentition before it is altered

by treatment.

• Finally, casts also serve as visual aids in discussions with the

patient and are useful for pre- and post-treatment

comparisons, as well as for reference at checkup visits

Clinical Photographs

• Color photographs are not essential, but they

are useful for recording the appearance of the

tissue before and after treatment.

• Photographs cannot always be relied on for

comparing subtle color changes in the gingiva,

but they do depict gingival morphologic

changes

• Review of the Initial Examination

– I f no emergency care is required, the patient is

dismissed and

– instructed as to when to report for the second

visit.

SECOND VISIT

Oral Examination

– Oral Hygiene. The cleanliness of the oral cavity is

appraised in terms of the extent of accumulated

food debris, plaque, materia alba, and tooth

surface stains .

– Disclosing solution may be used to detect plaque

that would otherwise be unnoticed.

– The amount of plaque detected, however, is not

necessarily related to the severity of the disease

present.

– For example, aggressive periodontitis is a

destructive type of periodontitis in which plaque is

scanty.

– Qualitative assessments of plaque are more

meaningful.

Mouth Odors.

• Termed as halitosis, also termed fetor ex ore,

fetor oris, and oral malodor,

• is foul or offensive odor emanating from the

oral cavity.

• Mouth odors may be of diagnostic

significance, and their origin may be either

oral or extraoral (remote).

• Halitosis is caused primarily by volatile sulfur

compounds, specifically, hydrogen sulfide and

methyl mercaptan, which result from the

bacterial putrefaction of proteins containing

sulfur amino acids.

• These products could be involved in the

transition from health to gingivitis and then to

periodontitis.

• Local sources of mouth odors are mainly the

– tongue and the gingival

– retention of odoriferous food particles on and between the

teeth

– coated tongue,

– necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG),

– dehydration states,

– caries,

– artificial dentures,

– smoker's breath,

– and healing surgical or extraction wounds.

• The fetid odor that is a characteristic of NUG

is easily identified.

• Chronic periodontitis with pocket formation

may also cause unpleasant mouth odor from

any accumulated debris and the increased rate

of putrefaction of the saliva

• Extraoral sources of mouth odors include various

infections

or lesions of

– the respiratory tract (bronchitis, pneumonia, bronchiectasis,

or others) and

– odors that are excreted through the lungs from aromatic

substances in the bloodstream, such as metabolites from

ingested foods or excretory products of cell metabolism.

– Alcoholic breath,

– the acetone odor of diabetes,

– and the uremic breath that accompanies kidney dysfunction.

Examination of the Oral Cavity.

• The entire oral cavity should be carefully examined.

• The examination should include the lips, floor of

the mouth, tongue, palate, and oropharyngeal

region, as well as the quality and quantity of saliva.

• Although findings may not be related to the

periodontal problem, they should enable the

dentist to detect any pathologic changes present in

the mouth.

Examination of Lymph Nodes.

• Because periodontal, periapical, and other oral

diseases may result in lymph node changes, the

diagnostician should routinely examine and

evaluate head and neck lymph nodes.

• Lymph nodes can become enlarged and/or

indurated as a result of an infectious episode,

malignant metastases, or residual fibrotic

changes.

• Inflammatory nodes become enlarged, palpable,

tender, and fairly immobile.

• The overlying skin may be red and warm. Patients

are often aware of the presence of "swollen

glands.“

• Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, NUG, and acute

periodontal abscesses may produce lymph node

enlargement.

• After successful therapy, lymph nodes return to

normal in a matter of days or a few weeks.

Examination of the Teeth

• The teeth are examined for caries, developmental

defects,

anomalies of tooth form, wasting, hypersensitivity, and

proximal contact relationships.

• Wasting Disease of the Teeth. Wasting is defined as any

gradual loss o f tooth substance characterized by the

formation of smooth, polished surfaces, without regard

to the possible mechanism of this loss. The forms of

wasting are erosion, abrasion, and attrition.

Erosion

• Erosion (cuneiform defect) is a sharply defined

wedge-shaped depression in the cervical area of the

facial

tooth surface.

• The long axis of the eroded area is perpendicular to the

vertical axis of the tooth.

• The surfaces are smooth, hard, and polished. Erosion

generally affects a group of teeth. In the early stages, it

may be confined to the enamel, but it generally extends to

involve the underlying dentin as well as the cementum.

• The cause of erosion is not known.

Decalcification by acid beverages or citrus

fruits, along with the combined effect of acid

salivary secretion and friction are suggested

causes.

Abrasion

• Abrasion refers to the loss of tooth substance induced

by mechanical wear other than that of mastication.

• Abrasion results in saucer-shaped or wedge-shaped

indentations with a smooth, shiny surface.

• Abrasion starts on exposed cementum surfaces rather than

on the enamel and extends to involve the dentin of the root.

• A sharp "ditching" around the cementoenamel junction

appears due to the softer cemental surface, as compared

with the much harder enamel surface.

Erosion

Abrasion

Dental Stains.

• These are pigmented deposits on the teeth.

They should be carefully examined to

determine their origin.

• Extrinsic Vs Intrinsic stains

Hypersensitivity.

• Root surfaces exposed by gingival recession

may be hypersensitive to thermal changes or

tactile stimulation.

• Patients often direct the operator to the

sensitive areas. These may be located by

gentle exploration with a probe or cold air.

Proximal Contact Relations.

• Slightly open contacts permit food impaction.

• The tightness of contacts should be checked by means

of clinical observation and with dental floss

• Abnormal contact relationships may also initiate

occlusal changes such as a shift in the median line

between the central incisors, labial version of the

maxillary canine, buccal or lingual displacement

of the posterior teeth, and an uneven relationship

of the marginal ridges.

Cheking contact point

Tooth Mobility.

• All teeth have a slight degree of physiologic

mobility, which varies for different teeth and at

different times of the day.“

• It is greatest on arising in the morning and

progressively decreases.

• The increased mobility in the morning is

attributed to slight extrusion of the tooth because

of limited occlusal contact during sleep. .

• During the waking hours, mobility is reduced

by chewing and swallowing forces, which

intrude the teeth in the sockets.

• These 24-hour variations are less marked

in persons with a healthy periodontium than

in those with occlusal habits such as bruxism

and clenching

• Single-rooted teeth have more mobility than

multirooted teeth, with incisors having the

most.

• Mobility is principally in a horizontal direction,

although some axial mobility occurs, to a

much lesser degree.

Tooth mobility occurs in two stages:

1. The initial or intrasocket stage is where the tooth

moves within the confines of the periodontal

ligament.

– This is associated with viscoelastic distortion of the

ligament and redistribution of the periodontal

fluids,interbundle content, and fibers .

– This initial movement occurs with forces of about 100

lb and is of the order of 0.05 to 0.10 mm (50 to 100

microns

2. The secondary stage

– occurs gradually and entails elastic deformation

of the alveolar bone in response to increased

horizontal forces.

– When a force of 500 Ibs is applied to the crown,

the resulting displacement is about 100 to 200

microns for incisors, 50 to 90 microns for canines,

8 to 10 microns for premolars, and 40 to 80

microns for molars .

• Mobility is graded according to the ease and

extent of tooth movement as follows

– Normal mobility

– Grade I: Slightly more than normal.

– Grade II: Moderately more than normal.

– Grade III: Severe mobility faciolingually and/or

mesiodistally, combined with vertical

displacement.

• Mobility beyond the physiologic range is

termed abnormal or pathologic.

• It is pathologic in that it exceeds the limits of

normal mobility values

• the periodontium is not necessarily diseased

at the time of examination.

• Increased mobility is caused by one or more of

the following factors:

• Loss of tooth support

– severity and distribution of bone loss

• Trauma from occlusion

– (i.e., injury produced by excessive occlusal forces

or incurred because of abnormal occlusal habits

such as bruxism and clenching) Mobility is also

increased by hypofunction.

• Extension of inflammation from the gingiva or

from theperiapex into the periodontal

ligament results in changesthat increase

mobility.

• Periodontal surgery temporarily increases

tooth mobility for a short period

• Tooth mobility is increased in pregnancy and is

sometimes associated with the menstrual cycle or

the use o f hormonal contraceptives.

– It occurs in patients with or without periodontal

disease, presumably because of physicochemical

changes in the periodontal tissues

• Pathologic processes of the jaws that destroy the

alveolar bone and/or the roots o f the teeth can

also result in mobility.

– Osteomyelitis and tumors of the jaw

Probing depth recession and mobility

Periodontal pocket

• A Periodontal probe

especially designed for the

PSR system.

• Note the ball tip and the

color coding, 3.5 to 5.5 mm

from

the probe tip.

B, Special sticker to be

placed in the patient's chart

with the code for each

sextant. (From the American

Dental Association

You might also like

- PMS SopDocument8 pagesPMS Sopstevekent40% (5)

- Understanding Periodontal Diseases: Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures in PracticeFrom EverandUnderstanding Periodontal Diseases: Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Examination of Patients With Periodontal DiseaseDocument7 pagesDiagnosis and Examination of Patients With Periodontal DiseaseHaider F YehyaNo ratings yet

- CG A021 01 Comprehensive Oral ExaminationDocument13 pagesCG A021 01 Comprehensive Oral Examinationmahmoud100% (1)

- Periodontal Therapy StatementDocument7 pagesPeriodontal Therapy StatementDiana AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Oral and Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument6 pagesOral and Maxillofacial Surgerysunaina chopraNo ratings yet

- Case HistoryDocument76 pagesCase Historyv.shivakumarNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis ClassDocument63 pagesDiagnosis ClassRiham AliNo ratings yet

- 1 Lec Examination and Diagnosis 2Document61 pages1 Lec Examination and Diagnosis 2سولاف اكبر عمر باباNo ratings yet

- E PerioTherapyDocument5 pagesE PerioTherapyFerdinan PasaribuNo ratings yet

- E PerioTherapyDocument5 pagesE PerioTherapymirfanulhaqNo ratings yet

- Chahal Paul S1611 DiagnosisPeriodontitisDocument11 pagesChahal Paul S1611 DiagnosisPeriodontitisShany SchwarzwaldNo ratings yet

- Princple of Oral DiagnosisDocument29 pagesPrincple of Oral DiagnosisIssa Waheeb100% (1)

- History, Diagnosis and Treatement Planning in Removable Partial DenturesDocument96 pagesHistory, Diagnosis and Treatement Planning in Removable Partial DenturesPriya BagalNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning - Removable Partial Denture Part-1Document38 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment Planning - Removable Partial Denture Part-1Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- History Taking and Clinical ExaminationDocument32 pagesHistory Taking and Clinical ExaminationYaser JasNo ratings yet

- 1 DiagnosisDocument102 pages1 Diagnosisyahia salahNo ratings yet

- FPD - LEC.SAS.5 Chart Medical Dental History Consent FormDocument11 pagesFPD - LEC.SAS.5 Chart Medical Dental History Consent FormabegailnalzaroNo ratings yet

- E PerioTherapyDocument5 pagesE PerioTherapyDoni Aldi L. TobingNo ratings yet

- History and ExaminationDocument28 pagesHistory and ExaminationDr. Hadi RaoNo ratings yet

- Short AnswersDocument41 pagesShort AnswersChander KantaNo ratings yet

- Guia de Tratamiento PeriodontalDocument6 pagesGuia de Tratamiento PeriodontalSam PicturNo ratings yet

- E PerioTherapyDocument5 pagesE PerioTherapyIova Elena-corinaNo ratings yet

- Psoriasis PPTTDocument39 pagesPsoriasis PPTTlikhithaNo ratings yet

- E PerioTherapyDocument5 pagesE PerioTherapymaherinoNo ratings yet

- SAQs VariousDocument16 pagesSAQs Variousapi-26291651100% (3)

- PerioDocument40 pagesPerioKavin SandhuNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Oral MedicineDocument40 pagesThe Practice of Oral Medicineامجد شاكرNo ratings yet

- Artículo PerioDocument5 pagesArtículo PerioMIRSHA IRAZEMA SAMAN HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- MJDF SyllabusDocument8 pagesMJDF SyllabusMahmoud AllaamNo ratings yet

- Patient History: Prof. Hoda ElguindyDocument14 pagesPatient History: Prof. Hoda Elguindyyahia salah100% (1)

- The Treatment Plan: Dr. Omar SolimanDocument36 pagesThe Treatment Plan: Dr. Omar SolimanSamwel EmadNo ratings yet

- Medicine IIDocument3 pagesMedicine IIDarwin D. J. LimNo ratings yet

- Hether - Case HistoryDocument42 pagesHether - Case HistoryIshan Narma100% (1)

- Evidence in Support of Periodontal Therapy-End PointsDocument31 pagesEvidence in Support of Periodontal Therapy-End PointsMohammad HarrisNo ratings yet

- Endo Diagnosis and TPDocument8 pagesEndo Diagnosis and TPJennifer HongNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Examination and Clinical Indices: Why Do We Do Examination?Document13 pagesPeriodontal Examination and Clinical Indices: Why Do We Do Examination?Jewana J. GhazalNo ratings yet

- Public Health DentistyDocument14 pagesPublic Health DentistyShibu SebastianNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and TT Planning in FDP 15Document15 pagesDiagnosis and TT Planning in FDP 15jaxine labialNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and TT Planning in FDP 15Document15 pagesDiagnosis and TT Planning in FDP 15jaxine labialNo ratings yet

- Patient Evaluation, Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: Chapter OutlineDocument13 pagesPatient Evaluation, Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: Chapter OutlineueloepNo ratings yet

- Glick 2021Document18 pagesGlick 2021dra.claudiamaria.tiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document9 pagesLecture 1Mustafa AliNo ratings yet

- A. Medical Review: B. Affective Sociological and Psychological Review. C. Dental HistoryDocument6 pagesA. Medical Review: B. Affective Sociological and Psychological Review. C. Dental HistoryHayder MaqsadNo ratings yet

- MFDS SyllabusDocument8 pagesMFDS SyllabusNazrin SarajuddinNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment PlanningDocument66 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment PlanningVincent SerNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis: Risk Factors For Partially Edentulous PatientDocument8 pagesDiagnosis: Risk Factors For Partially Edentulous PatientnjucyNo ratings yet

- Lec. 1 Pedodontics يفيطولا نسح.دDocument6 pagesLec. 1 Pedodontics يفيطولا نسح.دfghdhmdkhNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning For Edentulous or PotentiallyDocument73 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment Planning For Edentulous or PotentiallyRajsandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Concepts of ProsthoDocument22 pagesConcepts of ProsthoKirti SharmaNo ratings yet

- ClassificationDocument43 pagesClassificationsidra malikNo ratings yet

- Patient Data AnalyisDocument17 pagesPatient Data AnalyisSreya Sanil0% (1)

- Prosthodontics Lec 2 PDFDocument25 pagesProsthodontics Lec 2 PDFHassan QazaniNo ratings yet

- OMP512 Notes Spring 23Document100 pagesOMP512 Notes Spring 23Miran Miran Hussien Ahmed Hassan El MaghrabiNo ratings yet

- Case HistoryDocument42 pagesCase Historykomal nanavatiNo ratings yet

- What Is Epidemiology?Document23 pagesWhat Is Epidemiology?KoushikNo ratings yet

- Nutritional and Medical Management of Kidney StonesFrom EverandNutritional and Medical Management of Kidney StonesHaewook HanNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment in Urinary Bladder Pathology: Handbook of EndourologyFrom EverandEndoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment in Urinary Bladder Pathology: Handbook of EndourologyPetrisor Aurelian GeavleteRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Concise Guide to Clinical Dentistry: Common Prescriptions In Clinical DentistryFrom EverandConcise Guide to Clinical Dentistry: Common Prescriptions In Clinical DentistryNo ratings yet

- Personal Injury Litigation CourseDocument10 pagesPersonal Injury Litigation CourseMelissa HanoomansinghNo ratings yet

- Cass Review Interim Report Final Web AccessibleDocument112 pagesCass Review Interim Report Final Web AccessibleAvril CastañoNo ratings yet

- Birth Course Companion Ebook-3Document97 pagesBirth Course Companion Ebook-3shivanibatraNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER - 1 - Differential Diagnoses - 2011 - Small Animal Dermatology PDFDocument21 pagesCHAPTER - 1 - Differential Diagnoses - 2011 - Small Animal Dermatology PDFRanjani RajasekaranNo ratings yet

- Clientele and AudiencesDocument3 pagesClientele and AudiencesJOAN PINEDANo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka AsDocument1 pageDaftar Pustaka AsIchsanQuswainNo ratings yet

- Instruction: Check Under Correctly Done If Identified Skill Is Correctly Performed Incorrectly Done If Skill IsDocument3 pagesInstruction: Check Under Correctly Done If Identified Skill Is Correctly Performed Incorrectly Done If Skill IsSIR ONENo ratings yet

- Alternative Names: SleepwalkingDocument3 pagesAlternative Names: SleepwalkingRohanNo ratings yet

- Cpa Program: Submit Only If You Plan To Attend or Have Attended The ExamDocument4 pagesCpa Program: Submit Only If You Plan To Attend or Have Attended The ExamJagrit JainNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Effective CommunicationDocument4 pagesBarriers To Effective CommunicationMary Grace YañezNo ratings yet

- 1, Nurhamlin, Risdayati Dan IndrawatiDocument15 pages1, Nurhamlin, Risdayati Dan IndrawatiSophia Amelia PutriNo ratings yet

- diphenhydrAMINE BENADRYLDocument1 pagediphenhydrAMINE BENADRYLHope SerquiñaNo ratings yet

- Reading Test 3Document10 pagesReading Test 3Tuyết NhưNo ratings yet

- Promoting Smart Farming, Eco-Friendly and Innovative Technologies For Sustainable Coconut DevelopmentDocument4 pagesPromoting Smart Farming, Eco-Friendly and Innovative Technologies For Sustainable Coconut DevelopmentMuhammad Maulana Sidik0% (1)

- Midterm Exams NCM1531L - Care of The Older Persons LectureDocument50 pagesMidterm Exams NCM1531L - Care of The Older Persons Lecturejjmaxh20No ratings yet

- Lifelong WellnessDocument3 pagesLifelong Wellnessapi-404677881No ratings yet

- Northern India Textile Research Association, Ghaziabad: Antimicrobial (Anti Bacterial & Antifungal) TestingDocument2 pagesNorthern India Textile Research Association, Ghaziabad: Antimicrobial (Anti Bacterial & Antifungal) TestingNitraNtcNo ratings yet

- 433 Psychiatry Team Child PsychiatryDocument10 pages433 Psychiatry Team Child PsychiatrySherlina Rintik Tirta AyuNo ratings yet

- Dis-Infection With Ozone SystemDocument6 pagesDis-Infection With Ozone SystemSwaminathan ThayumanavanNo ratings yet

- Big Titty Teen Girlfriend Helps You Relax - Skylar Vox - Perfect Girlfriend - Alex AdamsDocument1 pageBig Titty Teen Girlfriend Helps You Relax - Skylar Vox - Perfect Girlfriend - Alex AdamsSexy AaravNo ratings yet

- Las Pe10 Day1 Week1 DonnaDocument4 pagesLas Pe10 Day1 Week1 DonnaBadeth AblaoNo ratings yet

- 1027 Application GuidelineDocument6 pages1027 Application GuidelineJORGEALEXERNo ratings yet

- NZMFMN Obstetric Doppler Guideline 2015Document16 pagesNZMFMN Obstetric Doppler Guideline 2015Nat NivlaNo ratings yet

- Lac NL - Spring 2021Document8 pagesLac NL - Spring 2021Ghassan NajmNo ratings yet

- The Man Box A Study On Being A Young Man in Australia PDFDocument64 pagesThe Man Box A Study On Being A Young Man in Australia PDFLuján SuárezNo ratings yet

- PR1 Covid 19 FinalDocument14 pagesPR1 Covid 19 FinalaaaaaNo ratings yet

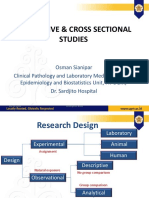

- Lecture 5 Research Design Observational Studies (Descriptive and Cross Sectional) - Dr. Dr. Osman Sianipar, DMM., MSC., Sp. PK (K) (2022)Document49 pagesLecture 5 Research Design Observational Studies (Descriptive and Cross Sectional) - Dr. Dr. Osman Sianipar, DMM., MSC., Sp. PK (K) (2022)Sheila Tirta AyumurtiNo ratings yet

- Mastitis Group 5Document14 pagesMastitis Group 5Michael Barfi OwusuNo ratings yet

- PM/Technical/03 Hid - Safety Report Assessment Guide: LPGDocument49 pagesPM/Technical/03 Hid - Safety Report Assessment Guide: LPGAbdus SamadNo ratings yet