Professional Documents

Culture Documents

VISISHTAADVAITHAM Vs ADVAITHAM

Uploaded by

rajCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

VISISHTAADVAITHAM Vs ADVAITHAM

Uploaded by

rajCopyright:

Available Formats

VISISHTAADVAITHAM Vs ADVAITHAM

Ramanuja’s differences with Shankara:

Adi Shankara had argued that all qualities or manifestations that can

be perceived are unreal and temporary. Ramanuja believed them to

be real and permanent and under the control of the Brahman. God can

be one despite the existence of attributes, because they cannot exist

alone; they are not independent entities. They are Prakaras or the

modes, Sesha or the accessories, and Niyama or the controlled aspects,

of the one Brahman.

In Ramanuja’s system of philosophy, the Lord (Narayana) has two

inseparable Prakaras or modes, namely, the world and the souls.

These are related to Him as the body is related to the soul. They have

no existence apart from Him. They inhere in Him as attributes in a

substance. Matter and souls constitute the body of the Lord. The Lord

is their indweller. He is the controlling Reality. Matter and souls are

the subordinate elements. They are termed Viseshanas, attributes. God

is the Viseshya or that which is qualified.

Ramanuja opines, wrong is the position of the Advaitins that

understanding the Upanishads without knowing and practicing

dharma can result in Brahman knowledge. The knowledge of

Brahman that ends spiritual ignorance is meditational, not

testimonial or verbal.

In contrast to Shankara, Ramanuja holds that there is no knowledge

source in support of the claim that there is a distinctionless

(homogeneous) Brahman. All knowledge sources reveal objects as

distinct from other objects. All experience reveals an object known in

some way or other beyond mere existence. Testimony depends on the

operation of distinct sentence parts (words with distinct meanings).

Thus the claim that testimony makes known that reality is

distinctionless is contradicted by the very nature of testimony as a

knowledge means. Even the simplest perceptual cognition reveals

something (Bessie) as qualified by something else (a broken hoof,

“Bessie has a broken hoof,” as known perceptually). Inference

depends on perception and makes the same distinct things known as

does perception.

He also holds that the Advaitin argument about prior absences and

no prior absence of consciousness is wrong. Similarly the Advaitin

understanding of a-vidya (not-Knowledge), which is the absence of

spiritual knowledge, is incorrect. “If the distinction between spiritual

knowledge and spiritual ignorance is unreal, then spiritual ignorance

and the self are one.”

The Seven objections to Shankara's Advaita:

Ramanuja picks out what he sees as seven fundamental flaws in the

Advaita philosophy to revise them. He argues:

I. The nature of Avidya: Avidya must be either real or unreal; there

is no other possibility. But neither of these is possible. If Avidya is

real, non-dualism collapses into dualism. If it is unreal, we are driven

to self-contradiction or infinite regress.

II. The incomprehensibility of Avidya: Advaitins claim that Avidya

is neither real nor unreal but incomprehensible, {anirvachaniya.} All

cognition is either of the real or the unreal: the Advaitin claim flies in

the face of experience, and accepting it would call into question all

cognition and render it unsafe.

III. The grounds of knowledge of Avidya: No pramana can establish

Avidya in the sense the Advaitin requires. Advaita philosophy

presents Avidya not as a mere lack of knowledge, as something

purely negative, but as an obscuring layer which covers Brahman

and is removed by true Brahma-vidya. Avidya is positive nescience

not mere ignorance. Ramanuja argues that positive nescience is

established neither by perception, nor by inference, nor by scriptural

testimony. On the contrary, Ramanuja argues, all cognition is of the

real.

IV. The locus of Avidya: Where is the Avidya that gives rise to the

(false) impression of the reality of the perceived world? There are two

possibilities; it could be Brahman's Avidya or the individual soul's

{jiva.} Neither is possible. Brahman is knowledge; Avidya cannot co-

exist as an attribute with a nature utterly incompatible with it. Nor

can the individual soul be the locus of Avidya: the existence of the

individual soul is due to Avidya; this would lead to a vicious circle.

V. Avidya's obscuration of the nature of Brahman: Sankara would

have us believe that the true nature of Brahman is somehow covered-

over or obscured by Avidya. Ramanuja regards this as an absurdity:

given that Advaita claims that Brahman is pure self-luminous

consciousness, obscuration must mean either preventing the

origination of this (impossible since Brahman is eternal) or the

destruction of it - equally absurd.

VI. The removal of Avidya by Brahma-vidya: Advaita claims that

Avidya has no beginning, but it is terminated and removed by

Brahma-vidya, the intuition of the reality of Brahman as pure,

undifferentiated consciousness. But Ramanuja denies the existence of

undifferentiated {nirguna} Brahman, arguing that whatever exists has

attributes: Brahman has infinite auspicious attributes. Liberation is a

matter of Divine Grace: no amount of learning or wisdom will deliver

us.

VII. The removal of Avidya: For the Advaitin, the bondage in which

we dwell before the attainment of Moksa is caused by Maya and

Avidya; knowledge of reality (Brahma-vidya) releases us. Ramanuja,

however, asserts that bondage is real. No kind of knowledge can

remove what is real. On the contrary, knowledge discloses the real; it

does not destroy it. And what exactly is the saving knowledge that

delivers us from bondage to Maya? If it is real then non-duality

collapses into duality; if it is unreal, then we face an utter absurdity.

Even though Bhagavad Ramanuja taught his followers to highly

respect all Sri Vaishnavas irrespective of caste, he firmly believed in

the tenets of Varnashrama Dharma.

His Saranagati philosophy emphasises that anyone, irrespective of

colour, creed, caste, sex and religion can surrender their mind, body

and soul to the Lotus feet of Lord Narayana and the God would

accept him/her. But if one surrenders to any other deva than

Vasudeva, such as Siva or Ganesha, he will have to be reborn as a

vaishnava.

You might also like

- Feudal PDFDocument146 pagesFeudal PDFGARIMA VISHNOINo ratings yet

- VisistadvaitaDocument146 pagesVisistadvaitabinodmaharajNo ratings yet

- Sleep and Various Schools of Indian PhilosophyDocument24 pagesSleep and Various Schools of Indian PhilosophyBrad YantzerNo ratings yet

- Ramayana by Kamala SubramaniamDocument852 pagesRamayana by Kamala Subramaniamnoway hoseNo ratings yet

- Sri Ramanujacharya LifeDocument286 pagesSri Ramanujacharya Lifedemoninsideme100% (1)

- Sulabha vs. King JanakDocument4 pagesSulabha vs. King JanakAditi SinghNo ratings yet

- Alvars and Their Celestial Songs Book Final 24-06-2015Document400 pagesAlvars and Their Celestial Songs Book Final 24-06-2015krishnankukuNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 3 PDFDocument37 pages10 - Chapter 3 PDFNavaneetha PhaniNo ratings yet

- Vivekachudamani 254-263Document4 pagesVivekachudamani 254-263Sudha RamNo ratings yet

- Legends of Siva Referred in The Saiva AgamasDocument14 pagesLegends of Siva Referred in The Saiva Agamassiddhanta100% (1)

- Vishnu PuranDocument6 pagesVishnu Puranshyam p joshiNo ratings yet

- Devi MahatmyamDocument13 pagesDevi Mahatmyamsundeepmv5483100% (1)

- Ramanauj CharitraDocument30 pagesRamanauj CharitramahendrachjoshiNo ratings yet

- Nama RamayanamDocument13 pagesNama Ramayanamiyer34No ratings yet

- Sri Ramanujacharya-Life HistoryDocument10 pagesSri Ramanujacharya-Life HistoryrajNo ratings yet

- Sukta SangrahaDocument80 pagesSukta SangrahaAshwinNo ratings yet

- Akshaya Tritiya - The Akha TeejDocument1 pageAkshaya Tritiya - The Akha TeejkvenkiNo ratings yet

- Swami Vivekananda and Sri Rama Krishna ParamahamsaDocument10 pagesSwami Vivekananda and Sri Rama Krishna Paramahamsanaveenchand_a6No ratings yet

- Vishnu Purana Sanskrit English OcrDocument671 pagesVishnu Purana Sanskrit English OcrAdvaita PurnaNo ratings yet

- 00 Introduction To UpanishadDocument27 pages00 Introduction To UpanishadKOFFI ANTOINENo ratings yet

- Lahgu Vasudeva MananamDocument198 pagesLahgu Vasudeva Mananamksanthanamala100% (2)

- Integrated Science of YagyaDocument33 pagesIntegrated Science of Yagyasksuman100% (17)

- Darshana Mala - दर्शनमालाDocument48 pagesDarshana Mala - दर्शनमालाSundararaman RamachandranNo ratings yet

- Yajurveda - WikipediaDocument15 pagesYajurveda - Wikipediagangeshwar gaurNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Life and Mystery of Death: An Exposition by Sage Sanatsujata in MahabharataDocument10 pagesMeaning of Life and Mystery of Death: An Exposition by Sage Sanatsujata in MahabharataVejella Prasad100% (1)

- Aditya Hridaya Stotra Meaning and Benefits PDFDocument16 pagesAditya Hridaya Stotra Meaning and Benefits PDFkeerthana buddhaNo ratings yet

- Oct 15, 2012 - INDIA (SUN) - This Is The List of 108 of The Most Important Slokas FromDocument26 pagesOct 15, 2012 - INDIA (SUN) - This Is The List of 108 of The Most Important Slokas FromVrajraj DasNo ratings yet

- Periyava Times - Aug 2016 - Vol 1 Issue 2Document4 pagesPeriyava Times - Aug 2016 - Vol 1 Issue 2PeriyavaTimes100% (3)

- Philosophy of Vishishtadvaita PDFDocument704 pagesPhilosophy of Vishishtadvaita PDFfghgfhfghNo ratings yet

- Chatusslokii EngDocument3 pagesChatusslokii EngdmadhavanurNo ratings yet

- 4 Sampradayas by Purusatraya SwamiDocument111 pages4 Sampradayas by Purusatraya SwamiyadogopalNo ratings yet

- RD 0508 OnlineDocument24 pagesRD 0508 Onlineksenthil77No ratings yet

- Daily MeditationsDocument164 pagesDaily MeditationsSanjay ContyNo ratings yet

- Ganapathi Japa VidhanamDocument5 pagesGanapathi Japa VidhanamMa Pitambra Jyotish KendraNo ratings yet

- The Holy Panchakshara Part IIIDocument64 pagesThe Holy Panchakshara Part IIIemail100% (1)

- Shvetashvatara UpanishadDocument4 pagesShvetashvatara UpanishadnieotyagiNo ratings yet

- Indian Scriptures: Vidya GitaDocument3 pagesIndian Scriptures: Vidya GitaMaheshawanukarNo ratings yet

- RudraDocument50 pagesRudraAntonio SilvazaNo ratings yet

- Ideal of Married LifeDocument15 pagesIdeal of Married LifevientoserenoNo ratings yet

- Sriranga SrivivEchana Samaalochanam. English Translation of SadhabishEkam Swami's Thamizh BookletDocument9 pagesSriranga SrivivEchana Samaalochanam. English Translation of SadhabishEkam Swami's Thamizh BookletvaasuranganNo ratings yet

- Good Drug Regulatory Practices - A Regulatory Affairs Quality Manual - (1998) PDFDocument433 pagesGood Drug Regulatory Practices - A Regulatory Affairs Quality Manual - (1998) PDFkamasanisNo ratings yet

- Krishna in Advaita Vedanta: The Supreme Brahman in Human FormDocument20 pagesKrishna in Advaita Vedanta: The Supreme Brahman in Human FormKrishnadas MNo ratings yet

- MadhvacaryaDocument509 pagesMadhvacaryaFrancisco Diaz BernuyNo ratings yet

- Parabrahm-Pratah Smaran Stotra With MeanDocument3 pagesParabrahm-Pratah Smaran Stotra With MeanshikhaNo ratings yet

- Periyar EVR's Critique On Priestly HinduismDocument13 pagesPeriyar EVR's Critique On Priestly HinduismkarupananNo ratings yet

- Skanda Purana 23 (AITM)Document258 pagesSkanda Purana 23 (AITM)Subal100% (2)

- The Nyaya System Is The Work of The Great Sage GautamaDocument6 pagesThe Nyaya System Is The Work of The Great Sage GautamaJohn JNo ratings yet

- AnukramaniDocument140 pagesAnukramaniSanatan SinhNo ratings yet

- Sapta Vidha Anupapatti - Seven UntenablesDocument2 pagesSapta Vidha Anupapatti - Seven Untenablesraj100% (1)

- Sankara Answer - FinalDocument2 pagesSankara Answer - Finalsaugat suriNo ratings yet

- Madhvacharya On BrahmanDocument2 pagesMadhvacharya On BrahmanDhiraj Hegde100% (1)

- Prominent Theistic Philosophers of IndiaDocument15 pagesProminent Theistic Philosophers of IndiaAmarSinghNo ratings yet

- VedantaDocument7 pagesVedantaAarushi RohillaNo ratings yet

- Ramanuja's Counter & Response K SadanandajiDocument7 pagesRamanuja's Counter & Response K SadanandajiAnonymous gJEu5X03No ratings yet

- Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta - Hindupedia, The Hindu EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesConsciousness in Advaita Vedanta - Hindupedia, The Hindu Encyclopediatejasdangodra99No ratings yet

- Sunyata Sunyata Is Translated As .Emptiness,. .Openness,. .Nothingness,. and .TheDocument3 pagesSunyata Sunyata Is Translated As .Emptiness,. .Openness,. .Nothingness,. and .TheShail GuptaNo ratings yet

- Classical Vedanta SubrationDocument11 pagesClassical Vedanta SubrationWilhelm Richard Wagner100% (1)

- Parallels in Buddhism Hinduism KabbalahDocument36 pagesParallels in Buddhism Hinduism KabbalahAdministrador ContaNo ratings yet

- Dasavatara Azhwar PasuramsDocument115 pagesDasavatara Azhwar Pasuramsraj100% (3)

- TurmericDocument50 pagesTurmericrajNo ratings yet

- VedarthaSangraham TathparyaDeepikaiDocument259 pagesVedarthaSangraham TathparyaDeepikairajNo ratings yet

- Garland of Vaisnava TruthsDocument26 pagesGarland of Vaisnava Truthsraj0% (1)

- The Vedanta SutrasDocument399 pagesThe Vedanta Sutrasapi-3716165No ratings yet

- Life Works of RamanujarDocument64 pagesLife Works of Ramanujarraj100% (2)

- Frequently Asked Questions On SrivaishnavamDocument19 pagesFrequently Asked Questions On SrivaishnavamrajNo ratings yet

- Artha PanchakamDocument13 pagesArtha Panchakamraj100% (2)

- ThirukkolurAmmalVarththaigal EnglishDocument57 pagesThirukkolurAmmalVarththaigal Englishraj100% (1)

- Gajendra Moksham-Significance and MeaningDocument13 pagesGajendra Moksham-Significance and Meaningraj100% (4)

- Ramanuja Darshanam: Bagavath Ramanujacharya - Moolavar, SrirangamDocument22 pagesRamanuja Darshanam: Bagavath Ramanujacharya - Moolavar, Srirangamraj100% (1)

- Nrsimhadev Shrines in Andhra PradeshDocument48 pagesNrsimhadev Shrines in Andhra Pradeshraj100% (2)

- Archiradi MargamDocument11 pagesArchiradi Margamraj88% (8)

- More Nectar in The Life of Sri RamanujacaryaDocument5 pagesMore Nectar in The Life of Sri RamanujacaryarajNo ratings yet

- NAmasankIrtana Medicine and ElixirDocument4 pagesNAmasankIrtana Medicine and ElixirrajNo ratings yet

- SriVaishnava Guidelines by RamanujaDocument3 pagesSriVaishnava Guidelines by Ramanujaraj100% (1)

- A LifeSketch of SriNampillaiDocument28 pagesA LifeSketch of SriNampillairaj100% (1)

- VEDIC WeddingDocument8 pagesVEDIC Weddingraj100% (2)

- Kaisika Ekadasi - SignificanceDocument3 pagesKaisika Ekadasi - SignificancerajNo ratings yet

- Eulogized by Lord SrIranganAthaDocument9 pagesEulogized by Lord SrIranganAtharaj100% (1)

- Jitante Stotram: Based On The Vyakhyanam of Sri Periyavaccan Pillai by Sri M.N. RamanujaDocument30 pagesJitante Stotram: Based On The Vyakhyanam of Sri Periyavaccan Pillai by Sri M.N. RamanujarajNo ratings yet

- Pi Ai LokåcåryaDocument88 pagesPi Ai Lokåcåryaraj100% (1)

- Bhojana Vidhi-Eating FoodDocument2 pagesBhojana Vidhi-Eating FoodrajNo ratings yet

- Narasimha Avtaaram NotesDocument8 pagesNarasimha Avtaaram NotesrajNo ratings yet

- Srimad Bhagavad Gita-GistDocument11 pagesSrimad Bhagavad Gita-GistrajNo ratings yet

- Bhajayathi Raja SthothramDocument11 pagesBhajayathi Raja SthothramrajNo ratings yet

- Samskaras Child Birth RelatedDocument48 pagesSamskaras Child Birth Relatedraj100% (2)

- Water Disaster - Avoid Bottled WaterDocument20 pagesWater Disaster - Avoid Bottled Watercopernicus_newton100% (2)

- Vighna Nivaraka Chaturthi - Ganesh ChaturthiDocument4 pagesVighna Nivaraka Chaturthi - Ganesh ChaturthirajNo ratings yet

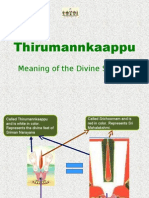

- Thirumannkaappu: Meaning of The Divine SymbolDocument4 pagesThirumannkaappu: Meaning of The Divine SymbolrajNo ratings yet

- TP AnalysisDocument6 pagesTP Analysiskp_mk2640No ratings yet

- ShikshasamuccayaDocument352 pagesShikshasamuccayaMartin Seidensticker100% (2)

- Free Talking TopicsDocument59 pagesFree Talking TopicsCraig BustilloNo ratings yet

- SAVol 8 June 2010 Indian Color Part 3Document272 pagesSAVol 8 June 2010 Indian Color Part 3SaptarishisAstrology67% (3)

- Ancient IndiansDocument70 pagesAncient Indiansjegan555No ratings yet

- Jason Crandell - Adho MukhaDocument5 pagesJason Crandell - Adho MukhanamastejasonNo ratings yet

- Arya-TArA SragdhArA Stotram of Sarvajnamitra - 1Document2 pagesArya-TArA SragdhArA Stotram of Sarvajnamitra - 1srikanthmicNo ratings yet

- The Thousand Names of Lord SivaDocument27 pagesThe Thousand Names of Lord SivaRaji SinghNo ratings yet

- Panchadasi of Sri Vidyaranya SvamiDocument7 pagesPanchadasi of Sri Vidyaranya SvamiAshish Karandikar0% (1)

- From Missionaries To Zen Masters: The Society of Jesus and Buddhism - BrillDocument23 pagesFrom Missionaries To Zen Masters: The Society of Jesus and Buddhism - BrillyanmaesNo ratings yet

- Wu Hsin QuotesThis Is The Present ConditionDocument371 pagesWu Hsin QuotesThis Is The Present ConditionVinod Dsouza100% (4)

- Glossary of Chinese TermsDocument22 pagesGlossary of Chinese TermsJigdrel77No ratings yet

- Jin Yong - Eagle Shooting Hero (Book 4) PDFDocument299 pagesJin Yong - Eagle Shooting Hero (Book 4) PDFTaruna UnitaraliNo ratings yet

- MYF Booklet PDFDocument76 pagesMYF Booklet PDFJim KirbyNo ratings yet

- Vajra Maha BhairavaDocument6 pagesVajra Maha BhairavaCLG100% (2)

- Ashtalakshmi StotramDocument3 pagesAshtalakshmi StotramAparna PrasadNo ratings yet

- Bhagya Aur PurusharthDocument3 pagesBhagya Aur PurusharthPriyam BajajNo ratings yet

- Hridaya VidyaDocument2 pagesHridaya VidyaNarayanan MuthuswamyNo ratings yet

- Ajanta Cave Art Work AnalysisDocument13 pagesAjanta Cave Art Work AnalysisannNo ratings yet

- Dhammapada AtthakathaDocument12 pagesDhammapada AtthakathaAlone Sky100% (2)

- All Sutras - English Hindi GujaratiDocument35 pagesAll Sutras - English Hindi GujaratiNeha Kapadia100% (4)

- The Vedanta Kesari July 2010Document58 pagesThe Vedanta Kesari July 2010Vejella PrasadNo ratings yet

- ทิพยมนต์กับการบำบัดโรคDocument7 pagesทิพยมนต์กับการบำบัดโรคtachetNo ratings yet

- Northern BuddhismDocument408 pagesNorthern BuddhismFaruq5100100% (1)

- Peter Harvey - Signless Meditations in Pali BuddhismDocument29 pagesPeter Harvey - Signless Meditations in Pali Buddhismkstan1122No ratings yet

- Saihoji TempleDocument5 pagesSaihoji TempleJustine MichealNo ratings yet

- Three Types of Appamada DhammaDocument6 pagesThree Types of Appamada DhammaDhamma SaraNo ratings yet

- Ten Avatars of VishnuDocument6 pagesTen Avatars of VishnuEdesanyaNo ratings yet

- Vedic Math Book Analysis Vedic Math SchoolDocument7 pagesVedic Math Book Analysis Vedic Math SchoolVedic Math SchoolNo ratings yet

- The United Nations Global GovernmentDocument37 pagesThe United Nations Global GovernmentValdomiro MoraisNo ratings yet