Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Newviews2 Display

Uploaded by

stuberCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Newviews2 Display

Uploaded by

stuberCopyright:

Available Formats

Less Reality: More Meaning Nothing is less

Quantifying imagery for the visual communicator. real than realism.

Details are confusing.

Stuart Medley, Edith Cowan University Psychology, art history and education are all ahead of graphic design with regard to quantifying the image. A useful model is the ‘realism continuum’ which distinguishes between pictures according to their relationship with visible reality (Dwyer, 1972; Wileman, 1993; McCloud, 1993) It is only by selection,

by elimination, by

emphasis that we get

at the real meaning

of things.

Georgia O’Keeffe

The colour photograph is our closest A grey-scale image is only slightly A silhouette or outline-only image has A range of studies in education have Stick figures have broad potential as A reduction in realism allows us to Letters and words are the ultimate

analogue to visible reality. Photographs removed from realism but immediately graphic impact that appeals to one of found that line drawings are better than pictures, including capturing gesture accentuate other aspects of a picture: visual abstraction, but they are still in

are very good at showing us specific suggests relationships between the ele- the major functions of the eye: edge photographs at communicating instruc- with gesture, and revealing their shape and colour considerations allow the realm of the visual. Letter shape

people and things, but they are pressed ments that a colour photograph detection. tional materials (Goldsmith, 1984). authored nature. us to apply a ‘system of seeing’ to a pic- and weight have an important bearing

into service by designers for other tasks does not. ture to suggest which elements belong on meaning separate from the content

to which they are less suited. with which others. Picture shape can of the text.

make a complex diagram seem

Photography: Arnold Newman approachable and simple.

‘Typography’ as a defining term has become Swiss modernism as the benchmark of A paradox reveals itself when we examine Face recognition experts have found that

Though these theories address the void in

graphic design that sits outside of typogra-

interchangeable with ‘graphic design’, thanks 20th century graphic design theory has an the human visual system: We are able to we recognise faces—and all kinds of other

phy, they can be used as a more appropriate

ill-informed reliance on realism through communicate more accurately through less objects—by mentally mapping their image

largely to the International Typographic Style photography: “the informational richness accurately rendered images. Visual reality The ‘spotlight’ or ‘zoom lens’ principle against norms and exaggerating the dif-

means to classify type itself. Most design

After Frank Werblin and Botond Roska: allows that the visual system may fo- audiences don’t know their transitional from

of the Swiss. While font choice and application and depth of the photographic image is at The brain re-assembles multiple basic

images from the eye. The eye gives

is not accepted on face value by the human cus on a small aspect of what’s in front

of it and effectively disregard the rest.

ferences. Caricature, and not realism, is a

their modern, but they will respond to open,

odds with the imperative for the generic, the off strong signals on edge-detection, organism but is a complex visual problem mechanism for visual memory: distillation

are seen as of paramount importance, image The Swiss typographers prescribed photo-

graphy as the way to present images in symbolic” (Lupton and Miller, 1999, p.133)

colour fields, vertical and horizontal

aspects of the environment. The brain to be solved.

Agency: Springer & Jacoby

Creative Direction: Stephan Ganser/ and exaggeration actually communicate

curving geometry or sharp points and high-

graphic design. adds detail from memory. Hans Jurgen Lewandowsk contrast. As designers we must remember

choice—virtually half of the communication Design: Joseph Müller-Brockmann

Photography: Axl Jansen more accurately to the psyche than the real

As with picture shape, letter shape can leave an that we are interested in how type looks—its

In 2000, 77% of awarded Australian graphic Once we begin to understand how the vis- thing (Rhodes, 1996); impression. Text may seem open or protective,

design equation—is neglected in the theory and designs contained photographic imagery ual system works we can make images that

for example, because of the type shapes in which

it is set.

image aspect—more than what it spells out.

in practice is left to the instinct of the designer. compared to 32% with illustrated imagery, play to its strengths: we can solve the object

and 9% whose content was type only. hypothesis problem on behalf of the viewer,

This reflects a long trend that may just be rather than re-present the problem of reality

The problem of specificity has

been known since photography’s changing. In 2008, 53% contained photo- through a photograph. We can solve or even create visual

inception. Photography works problems that lead to strong viewer

best when showing us a real graphic imagery compared to 30% with engagement. Impressive things can be

person, place or thing. achieved when pictures are made to

illustrated imagery and 16% type only. draw attention to the ways that we see.

Photography: Arnold Newman Illustration: after Milton Glaser

References:

Illustration: Milo Manara

Dwyer, F. M. A guide for improving visualized instruction. Learning Services, Contemporary Illustration and its Context. DGV, Berlin. p. 8 (2005).

State College, PA. Pennsylvania (1972). McCloud, S. Understanding Comics. Kitchen Sink Press (1993).

Eysenck, M. Psychology: An International Perspective. Psychology Press (2004) Meggs, P. Meggs’ history of graphic design. John Wiley and Sons,

Goldsmith, E. Research into illustration: an approach and a review. Cambridge Hoboken (1998).

University Press (1984) Rhodes, G. Superportraits: Caricatures and Recognition, Psychology Press,

Lupton, E and Miller, J.A. Design Writing Research, Writing on graphic design. East Sussex (1996).

Phaidon. London (1999) Wileman, R.E. Visual Communication. Educational Technology Publications,

Mareis, C. Illustration in Practice. In R. Klanten and H. Hellige (Eds.) Elusive: New Jersey, pp12-17 (1993).

You might also like

- Song of Freedom MadridDocument1 pageSong of Freedom Madridroger_lewis_14No ratings yet

- White Shade: The Real-World Primer for the Black Professional WomanFrom EverandWhite Shade: The Real-World Primer for the Black Professional WomanNo ratings yet

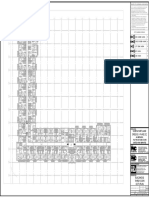

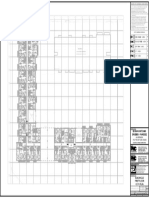

- 5382 Int 00 00 DR Me 320101 - P01Document1 page5382 Int 00 00 DR Me 320101 - P01Sanimouse MousesaniNo ratings yet

- Instant Assessments for Data Tracking, Grade 2: MathFrom EverandInstant Assessments for Data Tracking, Grade 2: MathNo ratings yet

- Daniels 70th Week (20.07.24)Document1 pageDaniels 70th Week (20.07.24)Mike MurphyNo ratings yet

- Advertising For Digital MediaDocument1 pageAdvertising For Digital Mediaaliarefnezhad2022No ratings yet

- Heuresis HBI 120 Backscatter X Ray ImagerDocument2 pagesHeuresis HBI 120 Backscatter X Ray ImagerBhagoo HatheyNo ratings yet

- Weare The ReasonDocument4 pagesWeare The ReasonClark Jan BernalesNo ratings yet

- IMSLP403255-PMLP652982-What Child Is This PDFDocument5 pagesIMSLP403255-PMLP652982-What Child Is This PDFszpt003No ratings yet

- PT - Adiprima - KPR - MB - 250tpd OCC - Line Rebuild - FYI - R0 - 20230112 To Customer-1Document1 pagePT - Adiprima - KPR - MB - 250tpd OCC - Line Rebuild - FYI - R0 - 20230112 To Customer-1Yudhi HalimNo ratings yet

- 37ladera3 Gasset 72Document1 page37ladera3 Gasset 72Jubayer SabujNo ratings yet

- A Little KnowledgeDocument12 pagesA Little KnowledgeRyan JonesNo ratings yet

- Unit Plans - CLNDocument4 pagesUnit Plans - CLNAnshul TiwariNo ratings yet

- Matsama Abil Hasan 2021 Form BedaharaDocument1 pageMatsama Abil Hasan 2021 Form Bedaharaelsa diadorapambayunNo ratings yet

- Dist 2 Zoning 2016Document1 pageDist 2 Zoning 2016Alteina CoradoNo ratings yet

- Sobha Hartland Greens - Phase 02: InvestmentsDocument1 pageSobha Hartland Greens - Phase 02: InvestmentsrajatNo ratings yet

- Random Processes SildesDocument24 pagesRandom Processes SildesSShadowNo ratings yet

- Cisne Cuello Negro PDFDocument12 pagesCisne Cuello Negro PDFJonny Malpartida AcostaNo ratings yet

- Mi Carnaval - Trumpet in BB 2Document2 pagesMi Carnaval - Trumpet in BB 2Oscar Moncayo OteroNo ratings yet

- Click! Game OverDocument49 pagesClick! Game Overekoga_emeriNo ratings yet

- Gas Flotation Package (Asbea-A-2703) 32294 Ponticelli - Al Shaheen PWTDocument54 pagesGas Flotation Package (Asbea-A-2703) 32294 Ponticelli - Al Shaheen PWTTĩnh Hồ TrungNo ratings yet

- Sobha Hartland Greens - Phase 02: InvestmentsDocument1 pageSobha Hartland Greens - Phase 02: InvestmentsrajatNo ratings yet

- IRIS LAYOUT PLAN FinalDocument1 pageIRIS LAYOUT PLAN FinalmaheshNo ratings yet

- Durham Census Tract MapDocument1 pageDurham Census Tract MapSarahNo ratings yet

- He Who Would Valiant BeDocument1 pageHe Who Would Valiant BeEssis Jn-Jo EssohNo ratings yet

- 17.05.2023 Future Print 2023Document1 page17.05.2023 Future Print 2023Guilherme AssisNo ratings yet

- 200 - C01 Existing - Demolition Elevations (AI 001)Document1 page200 - C01 Existing - Demolition Elevations (AI 001)Ekta JadejaNo ratings yet

- Shelby Views A & C US Copy Shop Pattern 36x118inDocument1 pageShelby Views A & C US Copy Shop Pattern 36x118inTatiana Codorniz100% (1)

- Prancha 02 Ambulatório e PoliclínicaDocument1 pagePrancha 02 Ambulatório e PoliclínicajosevitordinizzNo ratings yet

- Australian RMS Drawing LegendsDocument1 pageAustralian RMS Drawing LegendsrakhbirNo ratings yet

- Pet Suites Building SF 13,900 : BelowDocument1 pagePet Suites Building SF 13,900 : BelowchrisNo ratings yet

- Ain't Misbehavin' PDFDocument1 pageAin't Misbehavin' PDFnazotyuNo ratings yet

- Utawala-Bantu Sewers DWGDocument28 pagesUtawala-Bantu Sewers DWGAsaph MungaiNo ratings yet

- Routs Map - 2017Document1 pageRouts Map - 2017Nadeem AhmadNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu - Satoshi Yagisawa Revision by Nicolas GilDocument20 pagesMachu Picchu - Satoshi Yagisawa Revision by Nicolas Gil马跃No ratings yet

- Ysabel's Digital Fashion SketchesDocument8 pagesYsabel's Digital Fashion SketchesAo OkamiNo ratings yet

- UnitedStates 20210127 EpochTimesDocument52 pagesUnitedStates 20210127 EpochTimesKeithStewartNo ratings yet

- Draft 2Document1 pageDraft 2K61 ĐOÀN HỒ GIA HUYNo ratings yet

- Plan Showing 'F/N' Ward of Municipal Corporation of Greater MumbaiDocument1 pagePlan Showing 'F/N' Ward of Municipal Corporation of Greater MumbaiRational NationalNo ratings yet

- Application: IN THEDocument4 pagesApplication: IN THErutgersNo ratings yet

- The Willy Water's Blues: Gregory Dubrovsky (A Song Without Words and Meaning)Document1 pageThe Willy Water's Blues: Gregory Dubrovsky (A Song Without Words and Meaning)Григорий ДубровскийNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 PerceptionDocument1 pageChapter 3 PerceptionTIN NGUYEN BUI MINHNo ratings yet

- The Independent UGANDA - Issue 488Document44 pagesThe Independent UGANDA - Issue 488The Independent Magazine100% (1)

- V5 - V6 DH 81.27: Nombre:LOTE 6 Area:2.72Has Perimetro:856.361mDocument1 pageV5 - V6 DH 81.27: Nombre:LOTE 6 Area:2.72Has Perimetro:856.361mvanner alexander garcia estradaNo ratings yet

- Grupos 5 - Amigos y Algo MásDocument2 pagesGrupos 5 - Amigos y Algo Másluis2miguel-226362No ratings yet

- SajidHussain31dec23 1Document2 pagesSajidHussain31dec23 1Younis BabaNo ratings yet

- Suryanagar Phase-1 Layout Plan PDFDocument1 pageSuryanagar Phase-1 Layout Plan PDFLakshmanaLavuri80% (5)

- 1 DED Peningkatan Revitalisasi Terminal Tipe A BimokuDocument52 pages1 DED Peningkatan Revitalisasi Terminal Tipe A BimokuHakim fauziNo ratings yet

- Avengers Endgame - Portals (Piano)Document5 pagesAvengers Endgame - Portals (Piano)Ping the bossNo ratings yet

- Credit Concept Map I - Credit and Credit TransactionsDocument1 pageCredit Concept Map I - Credit and Credit TransactionsDonna Cel IsubolNo ratings yet

- Cópia de PROJETO URBANÍSTICO - RESIDENCIAL NOVA BENEVIDES I 2-3 01082023Document1 pageCópia de PROJETO URBANÍSTICO - RESIDENCIAL NOVA BENEVIDES I 2-3 01082023ReinaldoNo ratings yet

- Medina Kasba-Original 2Document1 pageMedina Kasba-Original 2Zineb ExoNo ratings yet

- Serban Nichifor: ReveryDocument1 pageSerban Nichifor: ReverySerban NichiforNo ratings yet

- 4 - RESC - Teo - 2122Document49 pages4 - RESC - Teo - 2122paulo.jcr.oliveiraNo ratings yet

- 457 691 1 SMDocument8 pages457 691 1 SMAditya SaputroNo ratings yet

- Regina Spektor - 2.99 Cent BluesDocument4 pagesRegina Spektor - 2.99 Cent BluesTaiane GomesNo ratings yet

- ECU S MedleyDocument36 pagesECU S MedleystuberNo ratings yet

- Newviews2 DisplayDocument1 pageNewviews2 DisplaystuberNo ratings yet

- Invoices Sample2Document1 pageInvoices Sample2stuberNo ratings yet

- Michael D'silva Editorial - Assign3Document1 pageMichael D'silva Editorial - Assign3stuberNo ratings yet

- 0barbican Brand Guidelines May07 PDFDocument56 pages0barbican Brand Guidelines May07 PDFRomán UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Cult of The Ugly, HellerDocument6 pagesCult of The Ugly, HellerstuberNo ratings yet

- Consistent Correlation Between Book Page and Type AreaDocument13 pagesConsistent Correlation Between Book Page and Type Areastuber100% (1)

- World Wealth FINALDocument1 pageWorld Wealth FINALstuberNo ratings yet

- Illustration Unit Editorial 2009Document2 pagesIllustration Unit Editorial 2009stuberNo ratings yet

- Brand Package 09Document1 pageBrand Package 09stuberNo ratings yet

- Steph CormackDocument1 pageSteph CormackstuberNo ratings yet

- Infodesign Marking KeyDocument1 pageInfodesign Marking KeystuberNo ratings yet

- Principles of PicturesDocument11 pagesPrinciples of Picturesstuber100% (1)

- Pictogram Marking KeyDocument1 pagePictogram Marking KeystuberNo ratings yet

- Vector Unit 2009Document2 pagesVector Unit 2009stuberNo ratings yet

- Vector Unit Brief1Document1 pageVector Unit Brief1stuberNo ratings yet