Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dome of The Rock

Uploaded by

riz2010Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dome of The Rock

Uploaded by

riz2010Copyright:

Available Formats

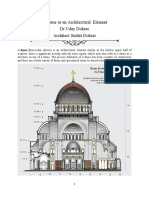

A dome is an element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere.

Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory. Corbel domes and true domes have been found in the ancient Middle East in modest buildings and tombs. The construction of the first technically advanced true domes began in the Roman Architectural Revolution,[1] when they were frequently used by the Romans to shape large interior spaces of temples and public buildings, such as the Pantheon. This tradition continued unabated after the adoption of Christianity in the Byzantine (East Roman) religious and secular architecture, culminating in the revolutionary pendentive dome of the 6th-century church Hagia Sophia. Squinches, the technique of making a transition from a square shaped room to a circular dome, was most likely invented by the ancient Persians. The Sassanid Empire initiated the construction of the first large-scale domes in Persia, with such royal buildings as the Palace of Ardashir, Sarvestan and Ghal'eh Dokhtar. With the Muslim conquest of Greek-Roman Syria, the Byzantine architectural style became a major influence on Muslim societies. Indeed the use of domes as a feature of Islamic architecture has gotten its roots from Roman Greater-Syria (see Dome of the Rock). An original tradition of using multiple domes was developed in the church architecture in Russia, which had adopted Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium. Russian domes are often gilded or brightly painted, and typically have a carcass and an outer shell made of wood or metal. The onion dome became another distinctive feature in the Russian architecture, often in combination with the tented roof. Domes in Western Europe became popular again during the Renaissance period, reaching a zenith in popularity during the early 18th century Baroque period. Reminiscent of the Roman senate, during the 19th century they became a feature of grand civic architecture. As a domestic feature the dome is less common, tending only to be a feature of the grandest houses and palaces during the Baroque period. Construction of domes in the Muslim world reached its peak during the 16th 18th centuries, when the Ottoman, Safavid and Mughal Empires, ruling an area of the World compromising North Africa, the Middle East and South- and Central Asia, applied lofty domes to their religious buildings to create a sense of heavenly transcendence. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque, the Shah Mosque and the Badshahi Mosque are primary examples of this style of architecture. Many domes, particularly those from the Renaissance and Baroque periods of architecture, are crowned by a lantern or cupola, a Medieval innovation which not only serves to admit light and vent air, but gives an extra dimension to the decorated interior of the dome.

Contents

[hide]

1 Characteristics 2 History o 2.1 Early history and primitive domes o 2.2 Roman and Byzantine domes

2.3 Chinese domes 2.4 Arabic and Western-European domes 2.5 Persian domes 2.6 Russian domes 2.7 Ottoman domes 2.8 Italian Renaissance domes 2.9 South-Asian and Mughal domes 2.10 Early modern period domes 2.11 Modern period domes 3 Symbolism 4 Influential domes 5 General types o 5.1 Onion dome o 5.2 Corbel dome o 5.3 Geodesic dome o 5.4 Oval dome o 5.5 Parabolic dome o 5.6 Polygonal dome o 5.7 Sail dome o 5.8 Saucer dome o 5.9 Umbrella dome 6 See also 7 References 8 Gallery

o o o o o o o o o

Characteristics[edit]

Comparison of a generic "true" arch (left) and a corbel arch (right). A dome can be thought of as an arch which has been rotated around its central vertical axis. Thus domes, like arches, have a great deal of structural strength when properly built and can span large open spaces without interior supports. Corbel domes achieve their shape by extending each horizontal layer of stones inward slightly farther than the previous, lower, one until they meet at the top. These are sometimes called false domes. True, or real, domes are formed with increasingly inward-angled layers of voussoirs which have ultimately turned 90 degrees from the base of the dome to the top.

A compound dome (red) with pendentives (yellow) from a sphere of greater radius than the dome. When the base of the dome does not match the plan of the supporting walls beneath it (for example, a circular dome on a square bay), techniques are employed to transition between the two. The simplest technique is to use diagonal lintels across the corners of the walls to create an octagonal base. Another is to use arches called squinchs to span the corners, which can support more weight. The invention of pendentives superseded the squinch technique.[2] Pendentives are triangular sections of a sphere used to transition from the flat surfaces of supporting walls to the round base of a dome. Domes can be divided into two kinds: simple and compound, depending on the use of pendentives.[3] In the case of the simple dome, the pendentives are part of the same sphere as the dome itself; however, such domes are rare.[4] In the case of the more common compound dome, the pendentives are part of the surface of a larger sphere below that of the dome itself and form a circular base for either the dome or a drum section.[3] Drums, also called tholobates or tambours, are cylindrical or polygonal walls supporting a dome which may contain windows. Domes have been constructed from a wide variety of building materials over the centuries: from mud to stone, wood, brick, concrete, metal, glass and plastic.

History[edit]

Early history and primitive domes[edit]

Apache wigwam, by Edward S. Curtis, 1903

Cultures from pre-history to modern times constructed domed dwellings using local materials. Although it is not known when the first dome was created, sporadic examples of early domed structures have been discovered. The earliest discovered may be four small dwellings made of Mammoth tusks and bones. The first was found by a farmer in Mezhirich, Ukraine, in 1965 while he was digging in his cellar and archaeologists unearthed three more.[5] They date from 19,280 - 11,700 BC.[6] In modern times, the creation of relatively simple dome-like structures has been documented among various indigenous peoples around the world. The Wigwam was made by Native Americans using arched branches or poles covered with grass or hides. The Ef people of central Africa construct similar structures, using leaves as shingles.[7] Another example is the Igloo, a shelter built from blocks of compact snow and used by the Inuit people, among others. The Himba people of Namibia construct "desert igloos" of wattle and daub for use as temporary shelters at seasonal cattle camps, and as permanent homes by the poor.[8]

Drawing of an Assyrian bas-relief from Nimrud showing domed structures The historical development from structures like these to more sophisticated domes is not well documented. That the dome was known to early Mesopotamia may explain the existence of domes in both China and the West in the first millennium BC.[9] Another explanation, however, is that the use of the dome shape in construction did not have a single point of origin and was common in virtually all cultures long before domes were constructed with enduring materials.[10] Small domes in corbelled stone or brick over round-plan houses go back to the Neolithic period in the ancient Near East, and served as dwellings for poorer people throughout the prehistoric period, but domes did not play an important role in monumental architecture.[11] The recent discoveries of seal impressions in the ancient site of Chogha Mish (c. 6800 to 3000 BC), located in the Susiana plains of Iran, show the extensive use of dome structures in mud-brick and adobe buildings.[12][13] Other examples of mud-brick buildings, which also seemed to employ the "true" dome technique have been excavated at Tell Arpachiyah, a Mesopotamian site of the Halaf (c. 6100 to 5400 BC) and Ubaid (ca. 5300 to 4000 BC) cultures.[14] Excavations at Tell al-Rimah have revealed brick domical vaults from about 2000 BC.[15] At the Sumerian Royal Cemetery of Ur, a "complete rubble dome built over a timber centring" was found among the chambers of the tombs for Meskalamdug and Puabi, dating to around 2500 BC.[16] Set in mud mortar, it was a "true dome with pendentives rounding off the

angles of the square chamber." Other small domes can be inferred from the remaining ground plans, such as one in the courtyard of Ur-Nammu's ziggurat, and in later shrines and temples of the 14th century BC.[17] Some monumental Mesopotamian buildings of the Kassite period are thought to have had brick domes, but the issue is unsettled due to insufficient evidence in what has survived of these structures.[11] A Neo-Assyrian bas-relief from Kuyunjik depicts domed buildings, although remains of such a structure in that ancient city have yet to be identified, perhaps due to the impermanent nature of sun-dried mudbrick construction.[10][18] However, because the relief depicts the Assyrian overland transport of a carved stone statue, the background buildings most likely refer to a foreign village, such as those at the foothills of the Lebanese mountains. The relief dates to the 8th century BC, while the use of domical structures in the Syrian region may go back as far as the fourth millennium BC.[10] Likewise, domed houses at Shulaveri in Georgia and Khirokitia, Cyprus, date back to around 6000 BC. The existing examples of beehive domes at Harran, Turkey, have been dated to the 19th century, and are similar to the trullos of Italy.[19] Ancient stone corbelled domes have been found from the Middle East to Western Europe. Corbelled beehive domes were used as granaries in Ancient Egypt from the first dynasty, in mastaba tombs of the Old Kingdom, as pressure-relieving devices in private brick pyramids of the New Kingdom, and as kilns and cellars. They have been found in brick and in stone.[20] The mastaba tombs of Seneb and of Neferi are examples.[11] In an area straddling the borders between Oman, UAE, and Bahrain, stone beehive tombs built above ground called "Hafeet graves", or "Mezyat graves", date to the Bronze Age period between 3200 and 2700 BC.[21][22] Similar above-ground tombs made of corbelled stone domes have been found in the fourth cataract region of Nubia with dates beginning in the second millennium BC.[23] Examples on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia have been dated to 2500 BC. The so-called Treasury of Atreus, a large Mycenaean tomb covered with a mound of earth, dates to around 1330 BC.[24] Some of the oldest traces of corbelled dome construction in the Iberian Peninsula can be found in the Province of Almera.[25] Wooden domes were evidently used in Etruria on the Italian peninsula from archaic times. Reproductions were preserved as rock-cut Etruscan tombs produced until the Roman Imperial period, and paintings at Pompeii show examples of them in the third style and later.[26] Wooden domes may also have been used in ancient Greece, over buildings such as the Tholos of Epidaurus, which is typically depicted with a shallow conical roof.[10] Evidence for such wooden domes over round buildings in Ancient Greece, if they existed, has not survived and the issue is much debated.[26] Rock-cut tombs in Alexandria suggest the possible use of domed ceilings in the architecture of Ptolemaic Egypt.[27] The earliest evidence of a Hellenistic dome is at the North Baths of Morgantina in Sicily, dated to the mid third century BC. The dome measured 5.75 metres in diameter over the circular hot room of the baths. It was made of terracotta tubes partially inserted into each other and arranged in parallel arches, which were then completely covered with mortar. It is also the earliest known example of this technique of tubular vault construction. A Hellenistic bathing complex in nearby Syracuse may also have used domes like these to cover its circular rooms. Another dome with the same parallel arch construction but more refined technique has been identified in the tepidarium at a Roman era bathing complex in Cabrera del Mar, Spain, and dated to the middle of the second century BC.[28]

In the Saar basin of the Germanic north of Europe, the domical shape was used in wooden construction over houses, tombs, temples, and city towers, and was translated into masonry construction only after the beginning of Roman rule.[10]

Roman and Byzantine domes[edit]

See also: List of Roman domes

Painting by Giovanni Paolo Pannini of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy, after its conversion to a church. Roman domes are found in baths, villas, palaces, and tombs. Oculi are common features.[26] They are customarily hemispherical in shape and partially or totally concealed on the exterior. In order to buttress the horizontal thrusts of a large hemispherical masonry dome, the supporting walls were built up beyond the base to at least the haunches of the dome and the dome was then also sometimes covered with a conical or polygonal roof.[10] Roman baths played a leading role in the development of domed construction in general, and monumental domes in particular. Modest domes in baths dating from the 2nd and 1st centuries BC are seen in Pompeii, in the cold rooms of the Terme Stabiane and the Terme del Foro.[26][27] According to Vitruvius, the temperature and humidity of domed warm rooms could be regulated by raising or lowering bronze discs located under the oculus.[27] Domes were particularly well suited to the hot rooms of baths circular in plan to facilitate even heating from the walls. However, the extensive use of domes did not occur before the 1st century AD.[29] Varro's book on agriculture describes an aviary with a wooden dome decorated with the eight winds which is compared by analogy to the eight winds depicted on the Tower of the Winds, which was built in Athens at about the same time. This aviary with its wooden dome may represent a fully developed type. Wooden domes in general would have allowed for very wide spans. Their earlier use may have inspired the development and introduction of large stone domes of previously unprecedented size.[26] Complex wooden forms were also necessary for dome centering and support during construction, and they seem to have eventually become more efficient and standardized over time.[29]

The first known large Roman dome is the so-called "Temple of Mercury" in Baiae, a concrete bath hall dating from the age of Augustus (27 BC 14 AD). There are five openings in the dome: a circular oculus and four square skylights.[26] The dome has a span of 21.5 meters and is the largest known dome to have been built before that of the Pantheon.[30] It is also the earliest preserved concrete dome.[29] The mortar and aggregate of Roman concrete was built up in horizontal layers laid by hand against wooden form-work with the thickness of the layers determined by the length of the workday, rather than being poured into a mold as concrete is today. Roman concrete domes were thus built similarly to the earlier corbel domes of the Mediterranean region, although they have different structural characteristics.[31] The dry concrete mixtures used by the Romans were compacted with rams to eliminate voids, and added animal blood acted as a water reducer.[32] While there are earlier examples in the Republican period and early Imperial period, the growth of domed construction increases under Emperor Nero and the Flavians in the 1st century, and during the 2nd century AD. The opulent palace architecture of the Emperor Nero (54-68 AD) marks an important development.[26] There is evidence of a dome in his Domus Transitoria at the intersection of two corridors, resting on four large piers, which may have had an oculus at the center. In Nero's Domus Aurea, or "Golden House", the walls of a large octagonal room transition to an octagonal domical vault, which then transitions to a dome with an oculus.[33] This octagonal and semicircular dome is made of concrete and the oculus is made of brick. The radial walls of the surrounding rooms buttress the dome, allowing the octagonal walls directly beneath it to contain large openings under flat arches and for the room itself to be unusually well-lit.[31] Another dome, made of wood, is reported in contemporary sources to have covered a dining hall in the palace, and may have been fitted such that perfume might spray from the ceiling.[26] The dome perpetually rotated on its base in imitation of the sky.[33] The expensive and lavish decoration of the palace caused such scandal that it was demolished soon after Nero's death and public buildings such as the Baths of Titus and the Colosseum were built in its place. The most famous and best preserved Roman dome and the largest is that of the Pantheon, a temple in Rome built by Emperor Hadrian as part of the Baths of Agrippa.[26] Dating from the 2nd century, it is an unreinforced concrete dome 43.4 meters wide resting on a circular wall, or rotunda, 6 meters thick. This rotunda, made of brick-faced concrete, contains a large number of relieving arches and is not solid. Seven interior niches and the entrance way divide the wall structurally into eight virtually independent piers. These openings and additional voids account for a quarter of the rotunda wall's volume. The only opening in the dome is the brick-lined oculus at the top, nine meters in diameter, which provides light and ventilation for the interior. The shallow coffering in the dome accounts for a less than five percent reduction in the dome's mass, and is mostly decorative. The aggregate material hand-placed in the concrete is heaviest at the base of the dome and changes to lighter materials as the height increases, dramatically reducing the stresses in the finished structure. In fact, many commentators cite the Pantheon as an example of the revolutionary possibilities for monolithic architecture provided by the use of Roman pozzolana concrete. However, vertical cracks seem to have developed very early, such that in practice the dome acts as an array of arches with a common keystone, rather than as a single unit. The exterior step-rings used to compress the "haunches" of the dome, which would not be necessary if the dome acted as a monolithic structure, may be an acknowledgement of this by the builders themselves. Such buttressing was common in Roman arch construction.[30] Hadrian is

believed to have held court in the Pantheon rotunda using the main apse opposite the entrance as a tribune, which may explain its very large size.[34] It remained the largest dome in the world for more than a millennium and is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome.[35] Segmental domes, made of radially concave wedges or of alternating concave and flat wedges, also appear under Hadrian in the 2nd century and most preserved examples of this style date from this period. Hadrian's Villa has examples at the Piazza D'Oro and in the semidome of the Serapeum. Recorded details of the decoration of the segmental dome at the Piazza D'Oro suggests it was made to evoke a billowing tent, perhaps in imitation of the canopies used by Hellenistic kings. Other examples exist at the Hadrianic baths of Otricoli and the so-called "Temple of Venus" at Baiae. This style of dome required complex centering and radially-oriented formwork to create its tight curves.[29] In the 3rd century, Imperial mausolea began to be built as domed rotundas rather than tumulus structures or other types, following similar monuments by private citizens. Pagan and Christian domed mausolea from this time can be differentiated in that the structures of the buildings also reflect their religious functions. The pagan buildings are typically two story, dimly lit, free-standing structures with a lower crypt area for the remains and an upper area for devotional sacrifice. Christian domed mausolea contain a single well-lit space and are usually attached to a church.[36] Examples from the 3rd century are the brick domes of the Mausoleum of Galerius, the Mausoleum of Diocletian, and the mausoleum at Tor de' Schiavi.[37] In the 4th century, Roman domes proliferated due to changes in the way domes were constructed, including advances in centering techniques and the use of brick ribbing. The socalled "Temple of Minerva Medica", for example, used brick ribs along with step-rings and lightweight pumice aggregate concrete to form a decagonal dome.[29] The material of choice in construction gradually transitioned during the 4th and 5th centuries from stone or concrete to lighter brick in thin shells.[38] The use of ribs stiffened the structure, allowing domes to be thinner with less massive supporting walls. Windows were often used in these walls and replaced the oculus as a source of light, although buttressing was sometimes necessary to compensate for large openings. The Mausoleum of Santa Costanza has windows beneath the dome and nothing but paired columns beneath that, using a surrounding barrel vault to buttress the structure.[33] Christian mausolea and shrines developed into the "centralized church" type, often with a dome over a raised central space.[2] The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, for example, was likely built with a wooden dome over the shrine by the end of the 4th century. The octagonal "Domus Aurea", or "Golden Octagon", built in 327 at the imperial palace of Antioch likewise had a domical roof, presumably of wood and covered with gilded lead.[10] Centralized buildings of circular or octagonal plan also became used for baptistries and reliquaries due to the suitability of those shapes for assembly around a single object.[2] Baptisteries began to be built in the manner of domed mausolea during the 4th century in Italy. The octagonal Lateran baptistery or the baptistery of the Holy Sepulchre may have been the first, and the style spread during the 5th century.[10] The Church of the Holy Apostles, or Apostoleion, probably planned by Constantine but built by his successor Constantius in the new capital city of Constantinople, combined the

congregational basilica with the centralized shrine. With a similar plan to that of the Church of Saint Simeon Stylites, four naves projected from a central rotunda containing Constantine's tomb and spaces for the tombs of the twelve Apostles.[2] Above the center may have been a clerestory with a wooden dome roofed with bronze sheeting and gold accents.[10] With the end of the Western Roman Empire, domes became a signature feature of the church architecture of the surviving Eastern Roman or "Byzantine" Empire.[18] The square bay with an overhead sail vault or dome on pendentives became the basic unit of architecture in the early Byzantine centuries, found in a variety of combinations. By the 5th century, structures with small-scale domed cross plans existed across the Christian world. Examples include the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, the martyrium attached to the Basilica of San Simpliciano, and churches in Macedonia and on the coast of Asia Minor.[38] Underground cisterns in Constantinople, such as the Cistern of Philoxenos and the Basilica Cistern, were composed of a grid of small domes resting on columns, rather than on groin vaults.[18] The first known domed basilica may have been a church at Meriamlik in southern Turkey, dated from 471494, although the ruins do not provide a definitive answer. It is possible earlier examples existed in Constantinople, where it has been suggested that the plan for the Meriamlik church itself was designed, but no domed basilica has been found there before the 6th century. The Church of St. Polyeuctus in Constantinople (524527) was apparently built as a large and lavish domed basilica similar to the Meriamlik church of fifty years before and to the later Hagia Irene of Emperor Justinian, by Anicia Juliana, the last descendent of the former Imperial House.[38]

The dome of Hagia Sophia, or Church of the Holy Wisdom, in Istanbul, Turkey 6th-century church building by the Emperor Justinian used the domed cross unit on a monumental scale, in keeping with Justinian's emphasis on bold architectural innovation. His church architecture emphasized the central dome. Centrally planned domed churches had been built since the 4th century for very particular functions, such as palace churches or martyria, with a slight widening of use around 500 AD, but Justinian's architects make the domed brick-vaulted central plan standard throughout the Roman east. This divergence with

the Roman west from the second third of the 6th century may be considered the beginning of "Byzantine" architecture.[38] The earliest existing of Justinian's domed buildings is the central plan Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople, completed by 536. The dome rests on an octagonal base created by eight arches on piers and is divided into sixteen sections. Those sections above the flat sides of the octagon are flat and contain a window at their base, alternating with sections from the corners of the octagon which are scalloped, creating an unusual kind of pumpkin dome.[39] After the Nika Revolt destroyed much of the city of Constantinople in 532, Justinian had the opportunity to rebuild. Both the churches of Hagia Irene ("Holy Peace") and Hagia Sophia ("Holy Wisdom") were burnt down. Both had been basilica plan churches and both were rebuilt as domed basilicas, although the Hagia Sophia was on a much grander scale.[39] Built by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus in Constantinople between 532 and 537, the Hagia Sophia has been called the greatest building in the world. It is an original and innovative design with no known precedents in the way it covers a basilica plan with dome and semi-domes. Periodic earthquakes in the region have caused three partial collapses of the dome and necessitated repairs. The precise shape of the original central dome completed in 537 was significantly different than the current one and, according to contemporary accounts, much bolder. Byzantine chronicler John Malalas reports that the original dome was 20 byzantine feet lower than its replacement. One theory is that the original dome continued the curve of the pendentives, creating a massive sail vault pierced with a ring of windows. A more recent theory raises the shallow cap of this dome (the portion above what are today the pendentives) on a relatively short recessed drum containing the windows, which is mentioned in an account by Procopius. This first dome partially collapsed in 558 and the design was then revised to the present profile. The current central dome is about 32 meters wide. It contains 40 ribs which radiate from the center of the dome and 40 windows at the base of the dome between the ribs. The dome and pendentives are supported by four large arches springing from four piers. Additionally, two huge semi-domes of similar proportion are placed on opposite sides of the central dome, which themselves contain smaller semi-domes between an additional four piers.[39] The brick dome also incorporated a wooden tension ring at its base to resist outward thrust and interrupt cracking, and iron cramps between the marble blocks of its cornice.[37] The octagonal Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, was completed in 547 and contains a terracotta dome.[40] Hollow amphorae were fitted inside one another to provide a lightweight structure and avoid additional buttressing.[41] The amphorae were arranged in a continuous spiral, which required minimal centering and formwork, but was not strong enough for large spans.[37] The dome was covered with a timber roof, which would be the favored practice for later medieval architects in Italy although it was unusual at the time.[41] Justinian also tore down the aging Church of the Holy Apostles and rebuilt it on a grander scale between 536 and 550.[42] The original building was a cruciform basilica with a central domed mausoleum. Justinian's replacement was likewise cruciform but with a central dome and four flanking domes. The central dome over the crossing had pendentives and windows in its base, while the four domes over the arms of the cross had pendentives but no windows. Justinian's Basilica of St. John at Ephesus and Venice's St Mark's Basilica are derivative of

this design.[39] More loosely, the Cathedral of St. Front and the Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua are also derived from this church.[37] With the decline in the empire's resources following losses in population and territory, domes in Byzantine architecture were used as part of more modest new buildings. The large-scale churches of Byzantium were, however, kept in good repair. The upper portion of the Church of Hagia Irene was thoroughly rebuilt after an earthquake in 740. The nave was re-covered with an elliptical domical vault hidden externally by a low cylinder on the roof, in place of the earlier barrel vaulted ceiling, and the original central dome from the Justinian era was replaced with one raised upon a high windowed drum. The barrel vaults supporting these two new domes were also extended out over the side aisles, creating cross-domed units.[42] These units became a standard element on a smaller scale in later Byzantine church architecture.[43] The Nea Ekklesia of Emperor Basil I was built in Constantinople around 880 as part of a substantial building renovation and construction program during his reign. It had five domes, which are known from literary sources, but different arrangements for them have been proposed under at least four different plans. One has the domes arranged in a cruciform pattern like those of the contemporaneous Church of St. Andrew at Peristerai or the much older Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Others arrange them in a quincunx pattern, with four minor domes in the corners of a square and a larger fifth in the center, as part of a cross-domed or cross-in-square plan.[44]

The Church of St. Panteleimon, Nerezi, Macedonia has five domes in a quincunx pattern. The Cross-in-square plan, with a single dome at the crossing or five domes in a quincunx pattern, became widely popular in the Middle Byzantine period.[38][45] This type of plan, with four columns supporting the dome at the crossing, was best suited for domes less than 7 meters wide and, from the tenth to the 14th centuries, a typical Byzantine dome measured less than 6 meters in diameter. For domes beyond that width, however, variations in the plan were required such as using piers in place of the columns and incorporating further buttressing around the core of the building.[43] In this period, domes were normally built to emphasize separate functional spaces, rather than as the modular ceiling units they had been earlier.[43] Resting domes on circular or polygonal drums pierced with windows eventually became the standard style, with regional characteristics.[38] The domes of the Church of the Holy Apostles, for example, appear to have been radically altered between 944 and 985 by the addition of windowed drums beneath all five domes and by raising the central dome higher than the others.[46] The distinctive rippling eaves design for the roofs of domes also begins in the 10th century. In mainland Greece, circular or octagonal drums became the most common while, in Constantinople, drums with twelve or fourteen sides were popular beginning in the 11th century.[38]

The domed-octagon plan is a variant of the cross-in-square plan.[45] The earliest extant example is the katholikon at the monastery of Hosios Loukas, built in the first half of the 11th century. Its square crossing bay is defined by four L-shaped piers which transition by conical squinches to an octagonal drum for the 9 meter wide dome.[42] The smaller monastic church at Daphni, c. 1080, uses a simpler version of this plan.[38] The katholikon of Nea Moni, a monastery on the island of Chios, was built some time between 1042 and 1055 and featured a nine sided, ribbed dome rising 15.62 meters above the floor (this collapsed in 1881 and was replaced with the slightly taller present version). The transition from the square naos to the round base of the drum is accomplished by eight conches, with those above the flat sides of the naos being relatively shallow and those in the corners of the being relatively narrow. The novelty of this technique in Byzantine architecture has led to it being dubbed the "island octagon" type, in contrast to the "mainland octagon" type of Hosios Loukas. Speculation on design influences have ranged from Arab influence transmitted via the recently built domed octagon chapels at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or the Al-Hakim Mosque in Islamic Cairo, to Caucasian buildings such as the Armenian Cathedral of the Holy Cross. Later copies of the Nea Moni, with alterations, include the churches of Agios Georgios Sykousis, Agioi Apostoli at Pyrghi, Panagia Krina, and the Church of the Metamorphosis in Chortiatis.[47] Another variant of the cross-in-square, the "so-called atrophied Greek cross plan", also provides greater support for a dome than the typical cross-in-square plan by using four piers projecting from the corners of an otherwise square naos, rather than four relatively slender columns. This design was used in the Chora Church of Constantinople in the 12th century after the previous cross-in-square structure was destroyed by an earthquake.[43] Byzantine domed buildings typically incorporated wooden tension rings at several levels within the structures, a technique frequently attributed as the later invention of Filippo Brunelleschi. Metal clamps between stone cornice blocks, metal tie rods, and metal chains were also used to stabilize domed construction.[43] Timber belts at the bases of domes help to stabilize the walls below them during earthquakes, but the domes themselves remain vulnerable to collapse.[48] The technique of using double shells for domes, although revived in the Renaissance, originated in Byzantine practice.[49] Byzantine domes and techniques of religious architecture spread to the surrounding Christian nations, such as Georgia and Armenia. Armenian church domes were initially wooden structures. Etchmiadzin Cathedral (c. 483) originally had a wooden dome covered by a wooden pyramidal roof before this was replaced with stone construction in 618. Churches with stone domes became the standard type after the 7th century, perhaps benefiting from a possible exodus of stonecutters from Syria, but the long traditions of wooden construction carried over stylistically. Some examples in stone as late as the 12th century are detailed imitations of clearly wooden prototypes.[10]

Chinese domes[edit]

Model of the Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb (25 AD 220 AD). Very little has survived of ancient Chinese architecture, due to the extensive use of timber as a building material. Brick and stone vaults used in tomb construction have survived, and the corbeled dome was used, rarely, in tombs and temples.[50] The earliest true domes found in Chinese tombs were shallow cloister vaults, called simian jieding, derived from the Han use of barrel vaulting. Unlike the cloister vaults of western Europe, the corners are rounded off as they rise.[51] A model of a tomb found with a shallow true dome from the late Han Dynasty (206 BC 220 AD) can be seen at the Guangzhou Museum (Canton).[52] Another, the Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb, found in Hong Kong in 1955, has a design common among Eastern Han Dynasty (25 AD 220 AD) tombs in South China: a barrel vaulted entrance leading to a domed front hall with barrel vaulted chambers branching from it in a cross shape. It is the only such tomb that has been found in Hong Kong and is exhibited as part of the Hong Kong Museum of History.[53][54] During the Three Kingdoms period (220280), the "cross-joint dome" (siyuxuanjinshi) was developed under the Wu and Western Jin dynasties, with arcs building out from the corners of a square room until they met and joined at the center. These domes were stronger, had a steeped angle, and could cover larger areas than the shallow cloister vaults. There are also corbel vaults used, called diese, although these are the weakest type.[51] Some tombs of the Song Dynasty (9601279) have beehive domes.[52]

Arabic and Western-European domes[edit]

The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem

Dome of Al Othman Mosque in Hawalli, Kuwait Seventeen years after the last Western Roman Emperor was deposed, Theodoric the Great was the Ostrogothic king of Italy. His building projects largely continued existing architectural conventions. His Arian Baptistry in Ravenna (c. 500), for example, closely echoes the Baptistry of Neon built before it.[55] Both baptistries are octagonal buildings with pyramidal roofs concealing interior domes. The Mausoleum of Theodoric, however, was understood by contemporaries to be remarkable.[55] Begun in 520, the 36-foot-wide (11 m) dome over the mausoleum was carved out of a single 440 ton slab of limestone and positioned some time between 522 and 526. The twelve brackets carved as part of the dome's exterior are thought to have been used to maneuver the piece into place. The choice of large limestone blocks for the structure is significant as the most common construction material in the West at that time was brick. It is likely that foreign artisans were brought to Ravenna to build the structure; possibly from Syria, where such stonework was used in contemporary buildings.[56] The Syria and Palestine area has a long tradition of domical architecture, including wooden domes in shapes described as "conoid", or similar to pine cones. When the Arab Muslim forces conquered the region, they employed local craftsmen for their buildings and, by the end of the 7th century, the dome had begun to become an architectural symbol of Islam. The rapidity of this adoption was likely aided by the Arab religious traditions, which predate Islam, of both domed structures to cover the burial places of ancestors and the use of a round tabernacle tent with a dome-like top made of red leather for housing idols.[10] Early versions of bulbous domes can be seen in mosaic illustrations in Syria dating to the Umayyad period. They were used to cover large buildings in Syria after the eleventh century.[57] The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the earliest surviving Islamic building, was completed in 691 by Umayyad caliph Abd Al-Malik.[58] Its design was that of a ciborium, or reliquary, such as those common to Byzantine martyria and the major Christian churches of the city.[59] The dome, a double shell design made of wood, is 20.44 meters in diameter and 30 meters high.[60] The dome's bulbous shape "probably dates from the eleventh century."[57] It is currently covered in gilded aluminum. Several restorations since 1958 to address structural damage have resulted in the extensive replacement of tiles, mosaics, ceilings, and walls such that "nearly everything that one sees in this marvelous building was put there in the second half of the twentieth century", but without significant change to its original form and structure.[61]

Byzantine workmen built the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus and its hemispherical dome for Sherif al Walid in 705. The dome rests upon an octagonal base formed by squinches.[18] Italian church architecture from the late sixth century to the end of the eighth century is influenced less by the trends of Constantinople than by a variety of Eastern provincial plans. With the crowning of Charlemagne as a new Roman Emperor, these influences were largely replaced in a revival of earlier Western building traditions. Occasional exceptions include examples of early quincunx churches at Milan and near Cassino.[38] Charlemagne built the Palatine Chapel at his palace at Aachen between 789 and its consecration in 805. The architect is thought to be Odo of Metz, although the quality of the ashlar construction has led to speculation about the work of outside masons.[62] The chapel's domed octagon design was influenced by Byzantine models such as the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, the Church of Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople, and perhaps the Chrysotriklinos, or "golden reception hall", of the Great Palace of Constantinople.[62][63] The octagonal domical vault measures 16.5 meters wide and 38 meters high. It was the largest dome north of the Alps at that time.[64] The dome of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (also called the Mosque of Uqba) built in the first half of the 9th century, has ribbed domes at each end of its central nave. The dome in front of the mihrab rests on an octogonal drum with slightly concave sides.[65][66] The Great Mosque of Crdoba, begun in 785 under the last of the Umayyad caliphs, was enlarged by Al-Hakam II between 961 and 976 to include four domes and a remodeled mihrab. The central dome, in front of the mihrab area, transitions from a square bay with decorative squinches to eight overlapping and intersecting arches which surround and support a scalloped dome.[41] Much of the Muslim architecture of Al-Andalus was lost as mosques were replaced by churches after the twelfth century, but the use of domes in surviving Mozarabic churches from the tenth century, such as the paneled dome at Santo Toms de las Ollas and the lobed domes at the Monastery of San Miguel de Escalada, likely reflects their use in contemporary mosque architecture.[67] Southern Italy, Sicily, and Venice served as outposts of Middle Byzantine architectural influence in Italy. That southern Italy was reconquered and ruled by a Byzantine governor from about 970 to 1071 explains the relatively large number of small and rustic Middle Byzantine-style churches found there, including the Cattolica in Stilo and S. Marco in Rossano. Both are cross-in-square churches with five small domes on drums in a quincunx pattern and date either to the period of Byzantine rule or after.[38] The church architecture of Sicily has fewer examples, having been conquered by Muslims in 827, but quincunx churches exist with single domes on tall central drums and either Byzantine pendentives or Islamic squinches.[38] Very little architecture from the Islamic period survives on the island. The Christian domed basilicas built in Sicily after the Norman Conquest of 1091, however, incorporate distinctly Islamic architectural elements. They include hemispherical domes positioned directly in front of apses, similar to the common positioning in mosques of domes directly in front of mihrabs, and the domes use four squinches for support, as do the domes of Islamic North Africa and Egypt. In other cases, domes with tall drums, engaged columns, and blind arcades exhibit Byzantine influences.[68] Examples include the Palatine Chapel at Palermo (1132-1143) and La Martorana (c. 1140s).[69]

Interior of St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy Venice's close mercantile links to the Byzantine empire resulted in the architecture of that city and its vicinity being a blend of Byzantine and northern Italian influences, although nothing from the ninth and tenth centuries has survived except for the foundations of the first St. Mark's Basilica.[38] The second and current St Mark's Basilica was built on the site between 1063 and 1072, replacing the earlier church while replicating its Greek cross plan. Five domes vault the interior (one each over the four arms of the cross and one in the center). These domes were built in the Byzantine style, in imitation of the now lost Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. Mounted over pendentives, each dome has a ring of windows at its base. Much higher wooden outer domes with lead roofing and cupolas were added between 1210 and 1270, allowing the church to be seen from a great distance.[70] In addition to allowing for a more imposing exterior, building two distinct shells in a dome improved weather protection. However, it was a rare practice before the 11th century.[37] The fluted and onion-shaped cupolas of the domes may have been added in the mid-fifteenth century to complement the ogee arches added to the facade in the late Gothic period. Their shape may have been influenced by the open and domed wooden pavilions of Persia or by other eastern models.[57] Domes in Romanesque architecture are generally found within crossing towers at the intersection of a church's nave and transept, which conceal the domes externally. The precise form of these differ from region to region.[41] Romanesque domes are typically octagonal in plan, possibly due to their use of corner squinches to translate a square bay into a suitable octagonal base.[4] They appear "in connection with basilicas almost throughout Europe" between 1050 and 1100.[71] Being a part of the Holy Roman Empire, the architecture of northern Italy developed differently than the rest of the Italian peninsula, especially after 1100. Churches were designed with vaulting from the outset, rather than as colonnaded basilicas with timber roofs, and many have octagonal domes with squinches over their crossings or choirs.[72] The earliest use of the octagonal cloister vault within an external housing at the crossing of a cruciform church may be at Acqui Cathedral in Acqui Terme, Italy, which was completed in 1067. This becomes increasingly popular as a Romanesque feature over the course of the next fifty years. The first Lombard church to have a lantern tower, concealing an octagonal

cloister vault, was San Nazaro in Milan, just after 1075. Many other churches followed suit in the next few decades, such as the Basilica of San Michele Maggiore in Pavia and the Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan.[73] The renovation of Speyer Cathedral, the largest of the Imperial Cathedrals of the Holy Roman Empire and the burial church of the Salian dynasty, was begun around 1080 by the Emperor Henry IV, soon after he had returned from a trip to Canossa in northern Italy. Although the church had only just been consecrated in 1061, Henry called upon craftsmen from across the empire for its renovation. The redesign included two octagonal cloister vaults within crossing towers, one at the east crossing with an external dwarf gallery and one at the west end. This was very soon imitated elsewhere and became the model for later Rhenish octagonal crossing domes, such as those of Worms Cathedral (c. 11201181) and Mainz Cathedral (c. 10811239).[72] Pisa Cathedral, built between 1063 and 1118, includes a high elliptical dome at the crossing of its nave and transept. The dome was one of the first in Romanesque architecture and is considered the masterpiece of Romanesque domes. Rising 48 meters above a rectangular bay, the shape of the dome was unique at the time.[74] The rectangular bay's dimensions are 18 meters by 13.5 meters. Squinches were used at the corners to create an elongated octagon and corbelling used to create an oval base for the dome. The tambour on which the dome rests dates to between 1090 and 1100, and it is likely that the dome itself was built at this time. There is evidence that the builders did not originally plan for the dome and decided on the novel shape to accommodate the rectangular crossing bay, which would make an octagonal cloister vault very difficult. Additionally, the dome may have originally been covered by a lantern tower which was removed in the 1300s, exposing the dome, to reduce weight on foundations not designed to support it. This would have been done no later than 1383, when the Gothic loggetta on the exterior of the dome was added, along with the buttressing arches on which it rests.[73] An aspiring competitor to Pisa, the city of Florence took the opposite side in the conflict between Pope and Emperor, siding with the Pope in Rome. This was reflected architecturally in the "proto-renaissance" style of its buildings.[72] The eight-sided Florence Baptistery, with its large octagonal cloister vault beneath a pyramidal roof, was likely built between 1059 and 1128, with the dome and attic built between 1090 and 1128. The lantern above the dome is dated to 1150.[75] It takes inspiration from the Pantheon in Rome for its oculus and much of its interior decoration, although the pointed dome is structurally similar to other Lombard domes, such as that of the later Cremona Baptistery.[73] The Crusades, beginning in 1095, also appear to have had an impact on domed architecture in Western Europe, particularly in the areas around the Mediterranean Sea.[76] The Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount of Jerusalem were taken to represent the Temple of Solomon and the Palace of Solomon, respectively. The Knights Templar, headquartered at the site, built a series of centrally-planned churches throughout Europe modeled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with the Dome of the Rock also an influence.[77] Examples include the church of the Vera Cruz at Segovia, the church of the Convento do Cristo at Tomar, a rotunda church in Paris destroyed during the French Revolution, and Temple Church in London. The Church of Saint Mary of Eunate was a pilgrims' burial church, rather than a Templar church, but may have been influenced by them.[78]

Medieval churches in southwest France at Solignac, Souillac, and Prigueux have five domes in a cruciform arrangement similar to that of St. Mark's Basilica. Dozens of other Romanesque churches in the region have a single nave with domed roofs.[74] Between the Garonne and Loire rivers there are known to have been at least seventy-seven churches whose naves were covered by a series of domes. Half of them are in the Prigord region. Most date to the twelfth century and sixty of them survive today.[41] The earliest may be Angoulme Cathedral, built from 1105 to 1128. Its long nave is covered by four stone domes on pendentives, springing from French pointed arches, the last of which covers the crossing and is surmounted by a stone lantern.[69][79] Cahors Cathedral (c.1100-1119) covers its nave with two large domes in the same manner and influenced the later building at Souillac. The cathedral of S. Front at Prigueux was built c. 11251150.[69] The use of pendentives to support domes in the Aquitaine region, rather than the squinches more typical of western medieval architecture, strongly implies a Byzantine influence.[80] A study in 1976 of Romanesque churches in the south of France documented 130 with oval plan domes, such as the those at Saint-Martin-de-Gurson, Dordogne and Balzac, Charente.[81] During the Reconquista, the Kingdom of Len in northern Spain built three churches famous for their domed crossing towers, called "cimborios", as it acquired new territories. The Cathedral of Zamora, the Cathedral of Salamanca, and the collegiate church of Toro were built around the middle of the 12th century. All three buildings have stone umbrella domes with sixteen ribs over windowed drums of either one or two stories, springing from pendentives. All three also have four small round towers engaged externally to the drums of the domes on their diagonal sides.[72] The architectural influences at work here have been much debated, with proposed origins ranging from Jerusalem, Islamic Spain, the Limousin region in western France, or a mixture of sources.[41] Another unusual Spanish example from the late 12th or early 13th century is the dome of The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Torres Del Ro, on the Way of St. James. The Way, a major pilgrimage route through northern Spain to the reputed burial place of St. James the Greater, attracted pilgrims from throughout Europe, especially after pilgrimage to Jerusalem was cut off. The difficulty of travel to Jerusalem for pilgrimage prompted some new churches to be built as a form of substitute, evoking the central plan and dome of Jerusalem's Church of the Holy Sepulchre with their own variant. The dome in this case, however, is most evocative of the central mihrab dome of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Over an octagonal room, the stone dome is formed by sixteen ribs, eight of which intersect with one another in a star pattern to define a smaller octagon at the center of the dome.[41] The domed "Decagon" nave of St. Gereon's Basilica in Cologne, Germany, a ten-sided space in an oval shape, was built between 1219 and 1227 upon the remaining low walls of a 4thcentury Roman martyrium.[82] The ribbed dome rises four stories and 34.55 meters above the floor, covering an oval area 21 meters long and 16.9 meters wide. It is unique among the twelve Romanesque churches of Cologne, and in European architecture in general, and may have been the largest dome built in this period in Western Europe until the completion of the dome of Florence Cathedral.[83][84] Gothic domes are uncommon due to the use of ribbed vaulting, and with the crossing usually focused instead by a tall steeple, but there are examples of small octagonal domes at cathedral crossings as the style developed from Romanesque.[41] Spaces of circular or octagonal plan were sometimes covered with vaults of a "double chevet" style, similar to the chevet apse vaulting in Gothic cathedrals. The crossing of Saint Nicholas at Blois is an example.[85]

Timber star vaults such as those over York Minster's octagonal Chapter house (ca. 1286 1296) and the elongated octagon plan of Wells Cathedral's Lady Chapel (ca.13201340) imitated much heavier stone vaulting.[41] The wooden vaulting over the crossing of Ely Cathedral in England was built after the original crossing tower collapsed in 1322. It was conceived by Alan of Walsingham and designed by master carpenter William Hurley.[86][87] Eight hammer vaults extend from eight piers over the 22 meter wide octagonal crossing and meet at the base of a large octagonal lantern, which is covered by a star vault.[72] Star-shaped domes are also found at the Moorish palace of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, which contains domed audience halls built to mirror the heavenly constellations. The Hall of the Abencerrajes (c. 133391) and the Hall of the two Sisters (c. 133354) are extraordinarily developed examples of muqarnas domes, taking the tradition of the squinch in Islamic architecture from a functional element in the zone of transition to a highly ornamental covering for the dome itself. The structural elements of these two domes are actually brick vaulting, but these are completely covered by the intricate mocrabe stalactites. The lacy and star-shaped crossing dome of Burgos Cathedral (1567) may have been inspired by these examples, in addition to that built over the cathedral's octagonal Chapel of the Condestable (148294) in the Gothic style.[41] In Egypt, bulbous cupolas on minarets were used beginning around 1330, spreading to Syria in the following century.[57] If an external lantern tower was removed from Pisa Cathedral in the 1300s, exposing the dome, one reason may have been to stay current with more recent projects in the region, such as the domed cathedrals of Siena and Florence. The dome of Siena Cathedral had an exposed profile as early as 1224.[73] Set over an irregular 17.7 meter wide hexagon with squinches to form an irregular twelve-sided base, the dome of Siena Cathedral has two shells and was completed in 1264.[88] No large dome had ever before been built over a hexagonal crossing.[89] Rapid progress on a radical expansion of the cathedral which would have involved replacing the existing dome with a larger one was halted not long after the city was struck with an outbreak of the Black Death in 1348.[89] The dome was originally topped with a copper orb, similar to that over Pisa's dome today, but this was replaced in 1385 by a cupola surmounted by a smaller sphere and cross.[90] The current lantern dates from the 17th century and the current outer dome is a 19th-century replacement.[91] It was only a few years after the city of Siena had decided to abandon the massive expansion and redesign of their Cathedral in 1355 that Florence decided to greatly expand theirs.[89] A plan for the dome of Florence Cathedral was settled by 1357.[73] However, in 1368 the plan was altered at the east end to increase the scale of the octagonal dome, widening it from 62 to 72 braccia, with the intent to further surpass the domes of Pisa and Siena.[86] The scale of this new dome was so ambitious that experts for the Opera del Duomo, the board supervising the construction, expressed the opinion as early as 1394 that the dome could not be accomplished.[92] The enlarged dome would span the entire 42 meter width of the three aisled nave, just 2 meters less than that of the Roman Pantheon, the largest dome in the world.[72] And because the distance between the angles of the octagon were even farther apart at 45.5 meters, the average span of the dome would be marginally wider than that of the Pantheon.[37] At 144 braccia, the height of the dome would evoke the holy number of the Heavenly Jerusalem mentioned in the Book of Revelation. By 1413, with the exception of one of the three apses, the east end of the church had been completed up to the windowed octagonal drum but the problem of building the huge dome did not yet have a solution.[72] In 1417, the

master builder in charge of the project retired and a competition for dome designs was begun in August 1418.[93] In the fifteenth century, pilgrimages to and flourishing trade relations with the Near East exposed the Low Countries of northwest Europe to the use of bulbous domes in the architecture of the Orient. Although the first expressions of their European use are in the backgrounds of paintings, architecture uses followed. The Dome of the Rock and its bulbous dome being so prominent in Jerusalem, such domes apparently became associated by visitors with the city itself. In Bruges, The Church of the Holy Cross, designed to symbolize the Holy Sepulchre, was finished with a gothic church tower capped by a bulbous cupola on a hexagonal shaft in 1428. Sometime between 1466 and 1500, a tower added to the Chapel of the Precious Blood was covered by a bulbous cupola very similar to Syrian minarets. Likewise, in Ghent, an octagonal staircase tower for the Church of St. Martin d'Ackerghem, built in the beginning of the sixteenth century, has a bulbous cupola like a minaret. These cupolas were made of wood covered with copper, as were the examples over turrets and towers in the Netherlands at the end of the fifteenth century, many of which have been lost. The earliest example from the Netherlands that has survived is the bulbous cupola built in 1511 over the town hall of Middelburg. Multi-story spires with truncated bulbous cupolas supporting smaller cupolas or crowns became popular in the following decades.[57]

Persian domes[edit]

Main article: Gonbad

The Shah Mosque, Isfahan, Iran. When completed in 1629, this mosque took the role of conducting the Friday-prayers. Persian architecture likely inherited an architectural tradition of dome-building dating back to the earliest Mesopotamian domes.[18] The remains of a large domed circular hall measuring 17 meters in diameter in the Parthian capital city of Nyssa has been dated to perhaps the first century AD. It "shows the existence of a monumental domical tradition in Central Asia which had hitherto been unknown and which seems to have preceded Roman Imperial monuments or at least to have grown independently from them."[94] The Sun Temple at Hatra appears to indicate a transition from columned halls with trabeated roofing to vaulted and domed construction in the first century AD, at least in Mesopotamia. The domed sanctuary hall of the temple was preceded by a barrel vaulted iwan, a combination that would be used by the subsequent Sassanid Empire.[95]

The Palace of Ardashir, constructed in AD 224. The building is composed of three large domes, among other structures.

Sasanids' Palace of Sarvestan Ruins of the Palace of Ardashir and Ghal'eh Dokhtar in Fars Province, built by Ardashir I (224240), demonstrate the use of the dome by the Sassanid Empire in what is today Iran. The structures have the earliest known examples of the Persian use of conical squinches to transition from a square room to the circular base of a dome. The large brick dome of the Sarvestan Palace, also in Fars but later in date, shows more elaborate decoration and four windows between the corner squinches. The building may have been a Fire temple.[96] Chahar-taqi, or "four vaults", were smaller Zoroastrian fire temple structures with four supports arranged in a square, connected by four arches, and covered by a central ovoid dome. The Niasar Zoroastrian temple in Kashan and the chahar-taqi in Darreh Shahr are examples.[97] Such temples, square domed buildings with entrances at the axes, inspired the forms of early mosques after the Islamic conquest of the empire.[41] During the early Islamic period, domed mausolea contributed greatly to the development and spread of the dome in Persia. By the 10th century, domed tombs had been built for Abbasid caliphs and Shiite martyrs. Pilgrimage to these sites may have helped to spread the form. The Samanid Mausoleum in Transoxiana dates to no later than 943 and is the first to have squinches create a regular octagon as a base for the dome, which then became the standard practice. The Arab-Ata Mausoleum, also in Transoxiana, may be dated to 97778 and uses muqarnas between the squinches for a more unified transition to the dome. Cylindrical or polygonal plan tower tombs with conical roofs over domes also exist beginning in the 11th century.[96] The earliest known masonry double shell domes are those of a pair of brick tower tombs from the 11th century in Kharraqan, Iran. The domes may have been modeled on earlier wooden double shell domes, such as that of the Dome of the Rock. It is also possible, because the upper portions of both of the outer shells are missing, that some portion of the outer domes may have been wooden.[37] These brick mausoleum domes were built without the use of centering, a technique developed in Persia.[93] The Il-Khanate period provided several innovations to dome-building that eventually enabled the Persians to construct much taller structures. These changes later paved the way for Safavid architecture. The taller proportions resulted primarily from the increased height of

the zone of transition, with the addition of a sixteen-sided section above the main zone of muqarnas squinches.[96] The pinnacle of Il-Khanate architecture was reached with the construction of the Mausoleum of ljait (130212) in Zanjan, Iran, which is topped by a dome that measures 50 m in height and 25 m in diameter, making it the 3rd largest and tallest masonry dome ever erected.[98] The thin, double-shelled dome was reinforced by arches between the layers.[96] A miniature painted at Samarkand shows that bulbous cupolas were used to cover small wooden pavilions in Persia by the beginning of the fifteenth century. They gradually gained in popularity.[57] The renaissance in Persian mosque and dome building came during the Safavid dynasty, when Shah Abbas, in 1598 initiated the reconstruction of Isfahan, with the Naqsh-e Jahan Square as the centerpiece of his new capital.[99] Architecturally, they borrowed heavily from Il-Khanate designs, but artistically, they elevated the designs to a new level. The distinct feature of Persian domes, which separates them from those domes constructed in the Christian world or the Ottoman and Mughal empires, was the colorful tiles, with which they covered the exterior of their domes, as they would on the interior. These domes soon numbered dozens in Isfahan, and the distinct, blue-colored shape would dominate the skyline of the city. Reflecting the light of the sun, these domes appeared like glittering turquoise gem and could be seen from miles away by travelers following the Silk road through Persia. This very distinct style of architecture was inherited to them from the Seljuq dynasty, who for centuries had used it in their mosque building throughout Central-Asia, but it was perfected during the Safavids when they invented the haft-rangi, or seven-colour style of tile burning, a process that enabled them to apply more colours to each tile, creating richer patterns, sweeter to the eye.[100] The colours that the Persians favoured were golden, white and turquoise patterns on a dark-blue background.[101] The extensive inscription bands of calligraphy and arabesque on most of the major buildings where carefully planned and executed by Ali Reza Abbasi, who was appointed head of the royal library and Master calligrapher at the Shah's court in 1598,[102] while Shaykh Bahai oversaw the construction projects. Reaching at total height of 53 meters, and with a diameter of 25 m at the base of the dome, the dome of Masjed-e Shah (Shah Mosque) would become the largest in the city when it was finished in 1629. It was built as a double-shelled dome, with 14 m spanning between the two layers, and resting on a sixteen-sided dome-chamber.[103][104] The Il-Khanate legacy also laid the groundwork for a separate brand of architectural style, the Timurid Islamic architecture, which later also became an inspiration to Mughal architects. During the 14th and 15th century, Timur and his successors adorned Samarkand and other Central-Asian cities with spectacular and stately edifices. The Sanctuary of Ahmed Yasawi, situated in southern Kazakhstan was never finished, but has got the largest existing brick dome in Central Asia, measuring 18.2 m in diameter. The dome exterior is covered with hexagonal green glazed tiles with gold patterns.[105]

Russian domes[edit]

Gilded onion domes of the Cathedral of the Annunciation, Moscow Kremlin.

Saint Basil's Cathedral (155561) in Moscow, Russia. Its distinctive onion domes date to the 1680s. The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture, which distinguishes Russia from other Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches, built just after the Christianization of Kievan Rus', were multi-domed, which has led some historians to speculate about how Russian pre-Christian pagan temples might have looked. Examples of these early churches are the 13-domed wooden Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod (989) and the 25-domed stone Desyatinnaya Church in Kiev (989 996). The number of domes typically has a symbolical meaning in Russian architecture, for example 13 domes symbolize Christ with 12 Apostles, while 25 domes means the same with an additional 12 Prophets of the Old Testament. The multiple domes of Russian churches were often comparatively smaller than Byzantine domes.[106][107] The earliest stone churches in Russia featured Byzantine style domes, however by the Early Modern era the onion dome had become the predominant form in traditional Russian architecture. The onion dome is a dome whose shape resembles an onion, after which they are named. Such domes are often larger in diameter than the drum upon which they are set, and their height usually exceeds their width. The whole bulbous structure tapers smoothly to a point. Though the earliest preserved Russian domes of such type date from the 16th century, illustrations from older chronicles indicate that they were at least used since the late 13th century. Like tented roofs, which were combined with and sometimes replaced domes in Russian architecture since the 16th century, onion domes initially were used only in wooden

churches and were introduced into stone architecture much later, where their carcasses continued to be made either of wood or metal on top of masonry drums.[108] Russian domes are often gilded or brightly painted. A dangerous technique of chemical gilding using mercury had been applied on some occasions until the mid-19th century, most notably in the giant dome of Saint Isaac's Cathedral. The more modern and safe method of gold electroplating was applied for the first time in gilding the domes of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, the tallest Eastern Orthodox church in the world.[109]

You might also like

- Fast FactsDocument61 pagesFast Factsgv2226No ratings yet

- The Dome As Architectural ElementDocument51 pagesThe Dome As Architectural ElementUday DokrasNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Architecture-Columnar Style & Massive TombsDocument5 pagesEgyptian Architecture-Columnar Style & Massive Tombsvartika chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Byzantine ArchitectureDocument21 pagesByzantine ArchitectureMenerson ManansalaNo ratings yet

- Indo Saracenic ArchitectureDocument11 pagesIndo Saracenic ArchitectureMenka Jaikanth100% (1)

- S 1 o 3 Ancient ArchitectureDocument32 pagesS 1 o 3 Ancient ArchitecturewhiteNo ratings yet

- Hoa Report GideonDocument49 pagesHoa Report GideonBernard CarbonNo ratings yet

- Islamic Architecture in IndiaDocument21 pagesIslamic Architecture in Indiashruti mantriNo ratings yet

- Hoac-I - Question Bank With Solved Answers PDFDocument92 pagesHoac-I - Question Bank With Solved Answers PDFTamilvanan GovindanNo ratings yet

- Evolution of The ArchDocument13 pagesEvolution of The ArchCrisencio M. Paner100% (2)

- Early Christian, Byzantine, and Islamic ArchitectureDocument32 pagesEarly Christian, Byzantine, and Islamic ArchitectureChloe HuangNo ratings yet

- Jagadamba Temple (R) : Inner Sanctum Vestibule Maha Mandapa Entrance PorchDocument4 pagesJagadamba Temple (R) : Inner Sanctum Vestibule Maha Mandapa Entrance PorchSiva RamanNo ratings yet

- Ancient Stupas of Sri LankaDocument15 pagesAncient Stupas of Sri Lankanyana varaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Architecture Styles Through the AgesDocument2 pagesJapanese Architecture Styles Through the AgesJaypee TanNo ratings yet

- Domed StructuresDocument18 pagesDomed StructuresReiner PinedaNo ratings yet

- BurmaDocument25 pagesBurmaShi YuNo ratings yet

- History of Domes from Ancient Rome to Modern StadiumsDocument9 pagesHistory of Domes from Ancient Rome to Modern StadiumsHimanshu ChincholeNo ratings yet

- Roman ArtDocument13 pagesRoman ArtDwardita Heisulher100% (1)

- Konark Sun TempleDocument5 pagesKonark Sun TemplePrashant Kumar100% (1)

- Mameluk ArchitectureDocument21 pagesMameluk ArchitectureKpatowary90No ratings yet

- History of ArchitectureDocument19 pagesHistory of ArchitectureSiva RamanNo ratings yet

- 02 Stability NotionsDocument7 pages02 Stability NotionsHema PenmatsaNo ratings yet

- Types of Domes ExplainedDocument12 pagesTypes of Domes ExplainedKartikey Singh100% (1)

- Literature Review: The Mosque in Islamic ArchitectureDocument3 pagesLiterature Review: The Mosque in Islamic ArchitectureABDIRAHMANNo ratings yet

- World's Largest Echo Dome - Gol GumbazDocument2 pagesWorld's Largest Echo Dome - Gol GumbazYogigolNo ratings yet

- Arches, Vaults and Domes StructuresDocument33 pagesArches, Vaults and Domes StructuresBhavika DabhiNo ratings yet

- HOA - Important Mosques in Islamic ArchitectureDocument23 pagesHOA - Important Mosques in Islamic ArchitectureSukritiNo ratings yet

- LintelDocument5 pagesLintelCésar Cortés GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Padmanabhampurampalace 100211074034 Phpapp01Document13 pagesPadmanabhampurampalace 100211074034 Phpapp01surekaNo ratings yet

- Indian ArchitectureDocument13 pagesIndian ArchitectureCliff Jason GulmaticoNo ratings yet

- The Architecture of Bidar FortDocument13 pagesThe Architecture of Bidar FortARVIND SAHANI100% (1)

- Colonial Architecture in WorldDocument11 pagesColonial Architecture in Worldsham_codeNo ratings yet

- Early Aryan Villages and Houses in the Indus ValleyDocument32 pagesEarly Aryan Villages and Houses in the Indus ValleyUjjwal Acharya100% (1)

- Hoa 3 NotesDocument18 pagesHoa 3 Notesanonuevo.chloe14No ratings yet

- Mosque EnvironmentDocument3 pagesMosque EnvironmentM'Nur RasyidNo ratings yet

- Mesoamerican Architecture Traditions and Temple PyramidsDocument1 pageMesoamerican Architecture Traditions and Temple PyramidsStephen Amir Prima ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Lecture-2 Part I (Islamic Architecture)Document15 pagesLecture-2 Part I (Islamic Architecture)Saad HafeezNo ratings yet

- FATEHPURDocument1 pageFATEHPURAnkit GargNo ratings yet

- BRITISH COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE IN INDIADocument243 pagesBRITISH COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE IN INDIAAishwaryaNo ratings yet

- Early Indian Dynasties' Architectural Styles & Their Modern InterpretationsDocument48 pagesEarly Indian Dynasties' Architectural Styles & Their Modern Interpretationsnagai jeswanthNo ratings yet

- StonesDocument51 pagesStonesanu_thilak100% (1)

- Sky TowerDocument19 pagesSky TowerAlcohol You LaterNo ratings yet

- Michelangelo at The Height of Renaissance and Beginning of Mannerism - Medici Chapel and Laurentian LibraryDocument5 pagesMichelangelo at The Height of Renaissance and Beginning of Mannerism - Medici Chapel and Laurentian LibraryAnqa ParvezNo ratings yet

- ARC226 History of Architecture 7Document105 pagesARC226 History of Architecture 7Partha Sarathi MishraNo ratings yet

- Regional Islamic ArchitectureDocument27 pagesRegional Islamic ArchitectureAnuj DagaNo ratings yet

- Unit-5 Indo AryanDocument61 pagesUnit-5 Indo AryanUd BsecNo ratings yet

- Islamic Architecture - Provincial StyleDocument27 pagesIslamic Architecture - Provincial Stylekevin tom100% (1)

- Pre Design OutlineDocument5 pagesPre Design Outlineapi-3831280100% (1)

- Khajuraho temples reveal Chandela architectural brillianceDocument9 pagesKhajuraho temples reveal Chandela architectural brillianceRidam GobreNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Dravidianarchitecture 160614134901 PDFDocument108 pagesUnit 4 Dravidianarchitecture 160614134901 PDFRatika100% (1)

- Aptoinn Nata Aesthetic Sensitivity Sample PaperDocument7 pagesAptoinn Nata Aesthetic Sensitivity Sample PaperkashishNo ratings yet

- Monolithic DomeDocument18 pagesMonolithic DomeSithu KannanNo ratings yet

- RomanDocument9 pagesRomanVickyjagNo ratings yet

- Buddhist ArchDocument41 pagesBuddhist ArchTanisha BhattNo ratings yet

- Patan Durbar SquareDocument14 pagesPatan Durbar SquareAnup PoudelNo ratings yet

- Mod 3.1 The Great Stupa at SanchiDocument17 pagesMod 3.1 The Great Stupa at SanchiArjun PrashanthNo ratings yet

- Islamic Architecture: History of Architecture & Human Settlement IiDocument81 pagesIslamic Architecture: History of Architecture & Human Settlement IiRonak PoladiaNo ratings yet

- Assign No 4 - Japanese ArchitectureDocument10 pagesAssign No 4 - Japanese ArchitectureElaiza Ann Taguse100% (2)

- Types of Hazard : Dormant - The Situation Has The Potential To Be Hazardous, But No People, Property, orDocument3 pagesTypes of Hazard : Dormant - The Situation Has The Potential To Be Hazardous, But No People, Property, orriz2010No ratings yet

- Isalmic WillDocument21 pagesIsalmic Willriz2010No ratings yet

- RectifierDocument18 pagesRectifierriz2010No ratings yet

- Micro ControllerDocument10 pagesMicro Controllerriz2010No ratings yet

- Negative Feedback AmplifierDocument12 pagesNegative Feedback Amplifierriz2010No ratings yet

- Electric-Power Transmission Is The Bulk Transfer Of: o o o oDocument17 pagesElectric-Power Transmission Is The Bulk Transfer Of: o o o oriz2010No ratings yet

- DC-to-DC Converter Switching Converter Transformer Change Voltage Push-Pull Circuit Buck-Boost ConvertersDocument3 pagesDC-to-DC Converter Switching Converter Transformer Change Voltage Push-Pull Circuit Buck-Boost Convertersriz2010No ratings yet

- Inheritance According To Islamic Sharia LawDocument7 pagesInheritance According To Islamic Sharia Lawmsohailahmed1No ratings yet

- An Electronic AmplifierDocument26 pagesAn Electronic Amplifierriz2010No ratings yet

- Power InverterDocument11 pagesPower Inverterriz2010No ratings yet

- Hot Chocolate Fudge Recipe Easy Ice Cream DessertDocument1 pageHot Chocolate Fudge Recipe Easy Ice Cream Dessertriz2010No ratings yet

- Geosynthetic Retaining WallsDocument2 pagesGeosynthetic Retaining Wallsriz2010No ratings yet

- What Is The Tallest Building?: WinnerDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Tallest Building?: Winnerriz2010No ratings yet

- Number Name Height (M) Height (FT) FloorsDocument4 pagesNumber Name Height (M) Height (FT) Floorsriz2010No ratings yet

- PLCDocument9 pagesPLCriz2010No ratings yet

- The Eden ProjectDocument7 pagesThe Eden Projectriz2010No ratings yet

- List of SensorsDocument9 pagesList of Sensorsriz2010No ratings yet

- Skyscraper: Navigation SearchDocument10 pagesSkyscraper: Navigation Searchriz2010No ratings yet

- Outline of EngineeringDocument9 pagesOutline of Engineeringriz2010No ratings yet

- Mechatronics Engineering Design ProcessDocument3 pagesMechatronics Engineering Design Processriz2010100% (1)

- Pipe ScheduleDocument2 pagesPipe Scheduleriz2010No ratings yet

- Instrumentation Is Defined As The Art and Science of Measurement and Control of ProcessDocument4 pagesInstrumentation Is Defined As The Art and Science of Measurement and Control of Processriz2010No ratings yet

- Control and InstrumentationDocument4 pagesControl and InstrumentationAbhishek RaoNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation Is Defined As The Art and Science of Measurement and Control of ProcessDocument4 pagesInstrumentation Is Defined As The Art and Science of Measurement and Control of Processriz2010No ratings yet

- Control and InstrumentationDocument4 pagesControl and InstrumentationAbhishek RaoNo ratings yet

- USS MaconDocument7 pagesUSS Maconriz2010No ratings yet

- Cables Wires and ConductorsDocument2 pagesCables Wires and Conductorsriz2010No ratings yet

- ControlDocument1 pageControlriz2010No ratings yet

- Petropipe MsdsDocument2 pagesPetropipe Msdsriz2010No ratings yet

- holly mass of st peter damianDocument7 pagesholly mass of st peter damianGaetan SangalaNo ratings yet

- World History TimelineDocument92 pagesWorld History TimelineMolai2010100% (1)

- Lanciano Eucharistic MiracleDocument1 pageLanciano Eucharistic Miraclepeterlimttk0% (1)

- The Chronicle of Prosper of Aquitaine, The Gallic Chronicle of 452, The Chronicle of Marius of AvenchesDocument18 pagesThe Chronicle of Prosper of Aquitaine, The Gallic Chronicle of 452, The Chronicle of Marius of AvenchesFrançois100% (6)

- Cristovao Ferreira PDFDocument48 pagesCristovao Ferreira PDFYamid CastiblancoNo ratings yet

- Free Traditional Catholic BooksDocument102 pagesFree Traditional Catholic BooksJonathan Frederick Lee Ching86% (7)

- The Spiritual Combat: Classic Edition - Lorenzo ScupoliDocument114 pagesThe Spiritual Combat: Classic Edition - Lorenzo ScupoliScriptoria Books100% (2)

- History and Origin of Nuestra Señora de GuiaDocument1 pageHistory and Origin of Nuestra Señora de GuiaOrl TrinidadNo ratings yet

- St Thomas Aquinas Feast Day January 28thDocument2 pagesSt Thomas Aquinas Feast Day January 28thLevi L. BinamiraNo ratings yet