Professional Documents

Culture Documents

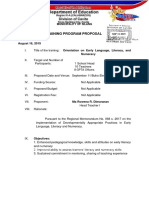

Elt Methods

Uploaded by

enicarmen337698Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Elt Methods

Uploaded by

enicarmen337698Copyright:

Available Formats

Language education: A Brief History Language education includes the teaching and learning of a language.

It can include improving a learner's native language; however, it is more commonly used with regard to second language ac uisition, that is, the learning of a foreign or second language, and that is the meaning that is treated in this article. As such, language education is a !ranch of applied linguistics. Ancient to medieval period Although the need to learn foreign languages is almost as old as human history itself, the origins of modern language education has its roots in the study and teaching of Latin. 500 years ago Latin was the dominant language of education, commerce, religion and government in much of the Western world. However, by the end of the 16th century, rench, !talian and "nglish dis#laced Latin as the languages of s#o$en and written communication. %he study of Latin diminished from the study of a living language to be used in the real world to a sub&ect in the school curriculum. 'uch decline brought about a new &ustification for its study. !t was then claimed that its study develo#ed intellectual abilities and the study of Latin grammar became an end in and of itself. ()rammar schools( from the 16th to 1*th centuries focused on teaching the grammatical as#ects of +lassical Latin. Advanced students continued grammar study with the addition of rhetoric. "#th century %he study of modern languages did not become #art of the curriculum of "uro#ean schools until the 1*th century. ,ased on the #urely academic study of Latin, students of modern languages did much of the same e-ercises, studying grammatical rules and translating abstract sentences. .ral wor$ was minimal/ instead students were re0uired to memorise grammatical rules and a##ly these to decode written te-ts in the target language. %his tradition1ins#ired method became $nown as the 2)rammar1%ranslation 3ethod2. "$th%&'th century (focus only on America) !nnovation in foreign language teaching began in the 14th century and, very ra#idly, in the 50th century, leading to a number of different methodologies, sometimes conflicting, each trying to be a ma&or im#rovement over the last or other contem#orary methods. %he earlist a##lied linguists, such as Henry 'weet 61*75114158, .tto 9es#ersen 61*601147:8 and Harold ;almer 61*<<114748 wor$ed on setting #rinci#les and a##roaches based on linguistic and #sychological theories, although they left many of the s#ecific #ractical details for others to devise. =nfortunately, those loo$ing at the history of foreign language education in the 50th century and the methods of teaching 6such as those related below8 might be tem#ted to thin$ that it is a history of failure. >ery few who study foreign languages in =.'. universities as a ma&or manage to reach something called (minimum #rofessional #roficiency( and even (reading $nowledge( re0uired for ;h? degree is com#arable only to what second year language students read. !n addition, very few American researchers can read and assess information written in languages other than "nglish and even a number of famous linguists are monolingual. However, anecdotal evidence for successful second or foreign language learning is easy to find, leading to a discre#ancy between these cases and the failure of most language #rograms to hel# ma$e second language ac0uisition research emotionally1charged. .lder methods and a##roaches such as the grammar translation method or the direct method are dis#osed of and even ridiculed as newer methods and a##roaches are invented and #romoted as the only and com#lete solution to the #roblem of the high failure rates of foreign language students. 3ost boo$s on language teaching list the various methods that have been used in the #ast, often ending with the author2s new method. %hese new methods seem to be created full1blown from the authors2 minds, as they generally give no credence to what was done before and how it relates to the new method. or e-am#le, descri#tive linguists seem to claim unhesitatingly that before their wor$, which lead to the audio1lingual method develo#ed for the =.'. Army in

World War !!, there were no scientifically1based language teaching methods. However, there is significant evidence to the contrary. !t is also often inferred or even stated that older methods were com#letely ineffective or have died out com#letely when even the oldest methods are still used 6e.g. the ,erlit@ version of the direct method8. 3uch of the reason for this is that #ro#onents of new methods have been so sure that their ideas are so new and so correct that they could not conceive that the older ones have enough validity to cause controversy and em#hasis on new scientific advances has tended to blind researchers to #recedents in older wor$. %he develo#ment of foreign language teaching is not linear. %here have been two ma&or branches in the field, em#irical and theoretical, which have almost com#letely1se#arate histories, with each gaining ground over the other at one #oint in time or another. "-am#les of researchers on the em#iricist side are 9es#erson, ;almer, Leonard ,loomfield who #romote mimicry and memori@ation with #attern drills. %hese methods follow from the basic em#iricist #osition that language ac0uisition basically results from habits formed by conditioning and drilling. !n its most e-treme form, language learning is basically the same as any other learning in any other s#ecies, human language being essentially the same as communication behaviors seen in other s#ecies. .n the other side, are rancois )ouin, 3.?. ,erlit@, "lime de 'au@A, whose rationalist theories of language ac0uisition dovetail with linguistic wor$ done by Boam +homs$y and others. %hese have led to a wider variety of teaching methods from grammar1translation, to )ouin2s (series method( or the direct methods of ,erlit@ and de 'au@A. With these methods, students generate original and meaningful sentences to gain a functional $nowledge of the rules of grammar. %his follows from the rationalist #osition that man is born to thin$ and language use is a uni0uely human trait im#ossible in other s#ecies. )iven that human languages share many common traits, the idea is that humans share a universal grammar which is built into our brain structure. %his allows us to create sentences that we have never heard before, but can still be immediately understood by anyone who understands the s#ecific language being s#o$en. %he rivalry of the two cam#s is intense, with little communication or coo#eration between them. *ethods of teaching foreign languages Approaches, *ethods and +echni ues %here are many methods of teaching languages. 'ome have fallen into relative obscurity and others are widely used/ still others have a small following, but offer useful insights. While sometimes confused, the terms (a##roach(, (method( and (techni0ue( are hierarchical conce#ts. An a##roach is a set of correlative assum#tions about the nature of language and language learning, but does not involve #rocedure or #rovide any details about how such assum#tions should translate into the classroom setting. 'uch can be related to second language ac0uisition theory. %here are three #rinci#al views at this levelC 1. %he structural view treats language as a system of structurally related elements to code meaning 6e.g. grammar8. 5. %he functional view sees language as a vehicle to e-#ress or accom#lish a certain function, such as re0uesting something. :. %he interactive view sees language as a vehicle for the creation and maintenance of social relations, focusing on #atters of moves, acts, negotiation and interaction found in conversational e-changes. %his view has been fairly dominant since the 14*0s. A method is a #lan for #resenting the language material to be learned and should be based u#on a selected a##roach. !n order for an a##roach to be translated into a method, an instructional system must be designed considering the ob&ectives of the teachingD learning, how the content is to be selected and organi@ed, the ty#es of tas$s to be #erformed, the roles of students and the roles of teachers. A techni0ue is a very s#ecific, concrete stratagem or tric$ designed to accom#lish an immediate ob&ective. 'uch are derived from the controlling method, and less1directly, from the a##roach.

+he grammar translation method %he grammar translation method instructs students in grammar, and #rovides vocabulary with direct translations to memori@e. !t was the #redominant method in "uro#e in the 14th century. 3ost instructors now ac$nowledge that this method is ineffective by itself. !t is now most commonly used in the traditional instruction of the classical languages. !n a##lied linguistics, the grammar translation method is a foreign language teaching method derived from the classical 6sometimes called traditional8 method of teaching )ree$ and Latin. %he method re0uires students to translate whole te-ts word for word and memori@e numerous grammatical rules and e-ce#tions as well as enormous vocabulary lists. %he goal of this method is to be able to read and translate literary master#ieces and classics. %hroughout "uro#e in the 1*th and 14th centuries, the education system was formed #rimarily around a conce#t called faculty #sychology. !n brief, this theory dictated that the body and mind were se#arate and the mind consisted of three #artsC the will, emotion, and intellect. !t was believed that the intellect could be shar#ened enough to eventually control the will and emotions. %he way to do this was through learning classical literature of the )ree$s and Eomans, as well as mathematics. Additionally, an adult with such an education was considered mentally #re#ared for the world and its challenges. !n the 14th century, modern languages and literatures begin to a##ear in schools. !t was believed that teaching modern languages was not useful for the develo#ment of mental disci#line and thus they were left out of the curriculum. As a result, te-tboo$s were essentially co#ied for the modern language classroom. !n America, the basic foundations of this method were used in most high school and college foreign language classrooms and were eventually re#laced by the audiolingual method among others. +lasses were conducted in the native language. A cha#ter in a distinctive te-tboo$ of this method would begin with a massive bilingual vocabulary list. )rammar #oints would come directly from the te-ts and be #resented conte-tually in the te-tboo$, to be e-#lained elaborately by the instructor. )rammar thus #rovided the rules for assembling words into sentences. %edious translation and grammar drills would be used to e-ercise and strengthen the $nowledge without much attention to content. 'entences would be deconstructed and translated. "ventually, entire te-ts would be translated from the target language into the native language and tests would often as$ students to re#licate classical te-ts in the target language. >ery little attention was #laced on #ronunciation or any communicative as#ects of the language. %he s$ill e-ercised was reading, and then only in the conte-t of translation Criticism %he method by definition has a very limited sco#e of ob&ectives. ,ecause s#ea$ing or any $ind of s#ontaneous creative out#ut was missing from the curriculum, students would often fail at s#ea$ing or even letter writing in the target language. A noteworthy 0uote describing the effect of this method comes from ,ahlsen, who was a student of ;lFt@, a ma&or #ro#onent of this method in the 14th century. !n commenting about writing letters or s#ea$ing he said he would be overcome with (a veritable forest of #aragra#hs, and an im#enetrable thic$et of grammatical rules.( Later, theorists such as >ietor, ;assy, ,erlit@, and 9es#ersen began to tal$ about what a new $ind of foreign language instruction needed, shedding light on what the grammar translation was missing. %hey su##orted teaching the language, not about the language, and teaching in the target language, em#hasi@ing s#eech as well as te-t. %hrough grammar translation, students lac$ed an active role in the classroom, often correcting their own wor$ and strictly following the te-tboo$. Conclusion %he grammar translation method stayed in schools until the 1460s, when a com#lete foreign language #edagogy evaluation was ta$ing #lace. !n the meantime, teachers e-#erimented with a##roaches li$e the direct method in #ost1war and ?e#ression era classrooms, but without much structure to follow. %he trusty grammar translation method set the #ace for many classrooms for many decades.

+he direct method %he direct method, sometimes also called natural method, is a method that refrains from using the learners2 native language and &ust uses the target language. !t was established in )ermany and rance around 1400 and are best re#resented by the methods devised by ,erlit@ and de 'au@A although neither claim originality and has been re1invented under other names. %he direct method o#erates on the idea that second language learning must be an imitation of first language learning, as this is the natural way humans learn any language 1 a child never relies on another language to learn its first language, and thus the mother tongue is not necessary to learn a foreign language. %his method #laces great stress on correct #ronunciation and the target language from outset. !t advocates teaching of oral s$ills at the e-#ense of every traditional aim of language teaching. 'uch methods rely on directly re#resenting an e-#erience into a linguistic construct rather than relying on abstractions li$e mimicry, translation and memori@ing grammar rules and vocabulary. According to this method, #rinted language and te-t must be $e#t away from second language learner for as long as #ossible, &ust as a first language learner does not use #rinted word until he has good gras# of s#eech. Learning of writing and s#elling should be delayed until after the #rinted word has been introduced, and grammar and translation should also be avoided because this would involve the a##lication of the learner2s first language. All above items must be avoided because they hinder the ac0uisition of a good oral #roficiency. %he method relies on a ste#1by1ste# #rogression based on 0uestion1and1answer sessions which begin with naming common ob&ects such as doors, #encils, floors, etc. !t #rovides a motivating start as the learner begins using a foreign language almost immediately. Lessons #rogress to verb forms and other grammatical structures with the goal of learning about thirty new words #er lesson. +haracteristic features of the direct method are teaching vocabulary through #antomiming, realia and other visuals teaching grammar by using an inductive a##roach 6i.e. having learners find out rules through the #resentation of ade0uate linguistic forms in the target language8 centrality of s#o$en language 6including a native1li$e #ronunciation8 focus on 0uestion1answer #atterns teacher1centeredness ,rinciples 1. +lassroom instructions are conducted e-clusively in the target language. 5. .nly everyday vocabulary and sentences are taught. 6%he language is made real.8 :. .ral communication s$ills are built u# in a carefully graded #rogression organi@ed around 0uestion1and1answer e-changes between teachers and students in small, intensive classes. 7. )rammar is taught inductively. 5. Bew teaching #oints are introduced orally. 6. +oncrete vocabulary is taught through demonstration, ob&ects, and #ictures/ abstract vocabulary is taught by association of ideas. <. ,oth s#eech and listening com#rehensions are taught. *. +orrect #ronunciation and grammar are em#hasi@ed. Historical conte-t %he direct method was an answer to the dissatisfaction with the grammar translation method, which teaches students in grammar and vocabulary through direct translations and thus focuses on the written language. %here was an attem#t to set u# such conditions as would imitate the mother tongue ac0uisition. or this reason the beginnings of these attem#ts were mar$ed as %he Batural methods. At the turn of the 1*th and 14th centuries, 'auveur and ran$e wrote #sychological roots regarding the associations made between the word and its meaning. %hey #ro#osed that in language teaching we should move within the target1language system and this was the first

stimulus for the rise of %he ?irect method. Later on, 'weet recogni@ed the limits of %he ?irect method and he #ro#osed a substantial change in methodology, and for this reason there was an introduction of the audio1 lingual method. +he audio%lingual method The Audio-Lingual Method (ALM) arose as a direct result of the need for foreign language proficiency in listening and speaking skills during and after World War II. It is closely tied to beha iorism! and thus made drilling! repetition! and habit-formation central elements of instruction. In the classroom! lessons "ere often organi#ed by grammatical structure and presented through short dialogs. $ften! students listened repeatedly to recordings of con ersations (for e%ample! in the language lab ) and focused on accurately mimicking the pronunciation and grammatical structures in these dialogs. &ackground %he audio1lingual method was develo#ed due to the =.'.2s entry into World War !!. %he government suddenly needed #eo#le who could carry on conversations fluently in a variety of languages such as )erman, rench, !talian, +hinese, 3alay, etc., and could wor$ as inter#reters, code1room assistants, and translators. However, since foreign language instruction in that country was heavily focused on reading instruction, no te-tboo$s, other materials or courses e-isted at the time, so new methods and materials had to be devised. %he Army '#eciali@ed %raining ;rogram created intensive #rograms based on the techni0ues Leonard ,loomfield and other linguists devised for Bative American languages, where students interacted intensively with native s#ea$ers and a linguist in guided conversations designed to decode its basic grammar and learn the vocabulary. %his (informant method( had great success with its small class si@es and motivated learners. %he Army '#eciali@ed %raining ;rogram only lasted a few years, but it gained a lot of attention from the #o#ular #ress and the academic community. +harles ries set u# the first "nglish Language !nstitute at the =niversity of 3ichigan, to train "nglish as a second or foreign language. 'imilar #rograms were created later at )eorgetown =niversity, =niversity of %e-as among others based on the methods and techni0ues used by the military. %he develo#ing method had much in common with the ,ritish oral a##roach although the two develo#ed inde#endently. %he audio1lingual method based itself on structural linguistics, focusing on grammar and contrastive analysis to find differences between the student2s native language and the target language in order to #re#are s#ecific materials to address #otential #roblems. %hese materials strongly em#hasi@ed drill as a way to avoid or eliminate these #roblems. %his first version of the method was originally called the oral method, the aural1oral method or the structural a##roach. %he audio1lingual method truly began to ta$e sha#e near the end of the 1450s, this time due government #ressure resulting from the s#ace race. +ourses and techni0ues were redesigned to add insights from behaviorist #sychology to the structural linguistics and constructive analysis already being used. =nder this method, students listen to or view recordings of language models acting in situations. 'tudents #ractice with a variety of drills, and the instructor em#hasi@es the use of the target language at all times. %he idea is that by reinforcing 2correct2 behaviors, students will ma$e them into habits. %he Audio1lingual method is the #roduct of three historical circumstances. or its views on language, audiolingualism drew on the wor$ of American linguists such as Leonard ,loomfield. %he #rime concern of American Linguistics at the early decades of the 50th century had been to document all the indigenous languages s#o$en in the ='A. However, because of the dearth of trained native teachers who would #rovide a theoretical descri#tion of the native languages, linguists had to rely on observation. or the same reason, a strong focus on oral language was develo#ed. At the same time, behaviourist #sychologists such as ,. . '$inner were forming the belief that all behaviour 6including language8 was learnt through re#etition and #ositive or negative reinforcement. %he third factor that enabled the birth of the Audio1lingual

method was the outbrea$ of World War !!, which created the need to #ost large number of American servicemen all over the world. !t was therefore necessary to #rovide these soldiers with at least basic verbal communication s$ills. =nsur#risingly, the new method relied on the #revailing scientific methods of the time, observation and re#etition, which were also admirably suited to teaching en masse. ,ecause of the influence of the military, early versions of the audio1 lingualism came to be $nown as the Garmy method.H ?ue to wea$nesses in #erformance, and more im#ortantly because of Boam +homs$y2s theoretical attac$ on language learning as a set of habits, audio1lingual methods are rarely the #rimary method of instruction today. However, elements of the method still survive in many te-tboo$s. 'ractice %he Audio1Lingual 3ethod, or the Army 3ethod or also the Bew Iey, is a style of teaching used in teaching foreign languages. !t is based on behaviorist theory, which #rofesses that certain traits of living things, and in this case humans, could be trained through a system of reinforcementJcorrect use of a trait would receive #ositive feedbac$ while incorrect use of that trait would receive negative feedbac$. %his a##roach to language learning was similar to another, earlier method called the ?irect method. Li$e the ?irect 3ethod, the Audio1Lingual 3ethod advised that students be taught a language directly, without using the students2 native language to e-#lain new words or grammar in the target language. However, unli$e the ?irect 3ethod, the Audiolingual 3ethod didnKt focus on teaching vocabulary. Eather, the teacher drilled students in the use of grammar. A##lied to language instruction, and often within the conte-t of the language lab, this means that the instructor would #resent the correct model of a sentence and the students would have to re#eat it. %he teacher would then continue by #resenting new words for the students to sam#le in the same structure. !n audio1lingualism, there is no e-#licit grammar instructionJ everything is sim#ly memori@ed in form. %he idea is for the students to #ractice the #articular construct until they can use it s#ontaneously. !n this manner, the lessons are built on static drills in which the students have little or no control on their own out#ut/ the teacher is e-#ecting a #articular res#onse and not #roviding that will result in a student receiving negative feedbac$. %his ty#e of activity, for the foundation of language learning, is in direct o##osition with communicative language teaching. +harles ries, the director of the "nglish Language !nstitute at the =niversity of 3ichigan, the first of its $ind in the =nited 'tates, believed that learning structure, or grammar was the starting #oint for the student. !n other words, it was the studentsK &ob to orally recite the basic sentence #atterns and grammatical structures. %he students were only given Genough vocabulary to ma$e such drills #ossible.H 6Eichards, 9.+. et1al. 14*68. ries later included #rinci#les for behavioural #sychology, as develo#ed by ,. . '$inner, into this method. Oral Drills ?rills and #attern #ractice are ty#ical of the Audiolingual method. 6Eichards, 9.+. et1al. 14*68 %hese include Ee#etition C where the student re#eats an utterance as soon as he hears it !nflection C Where one word in a sentence a##ears in another form when re#eated Ee#lacement C Where one word is re#laced by another Eestatement C %he student re1#hrases an utterance Examples !nflection C %eacher C ! ate the sand"ich. 'tudent C ! ate the sand"iches. Ee#lacement C %eacher C He bought the car for half1#rice. 'tudent C He bought it for half1#rice. Eestatement C %eacher C Tell me not to shave so often. 'tudent C (on)t shave so oftenL %he following e-am#le illustrates how more than one sort of drill can be incor#orated into one #ractice session C G%eacherC %here2s a cu# on the table ... re#eat

'tudentsC %here2s a cu# on the table %eacherC '#oon 'tudentsC %here2s a s#oon on the table %eacherC ,oo$ 'tudentsC %here2s a boo$ on the table %eacherC .n the chair 'tudentsC %here2s a boo$ on the chair etc.H %hus lessons in the classroom focus on the correct imitation of the teacher by the students. Bot only are the students e-#ected to #roduce the correct out#ut, but attention is also #aid to correct #ronunciation. Although correct grammar is e-#ected in usage, no e-#licit grammatical instruction is given. urthermore, the target language is the only language to be used in the classroom. 3odern day im#lementations are more la- on this last re0uirement. Fall from popularity !n the late 1450s, the theoretical under#innings of the method were 0uestioned by linguists such as Boam +homs$y, who #ointed out the limitations of structural linguistics. %he relevance of behaviorist #sychology to language learning was also 0uestioned, most famously by +homs$y2s review of ,. . '$inner2s >erbal ,ehavior in 1454. %he audio1lingual method was thus de#rived of its scientific credibility and it was only a matter of time before the effectiveness of the method itself was 0uestioned. !n 1467, Wilga Eivers released a criti0ue of the method in her boo$, G%he ;sychologist and the oreign Language %eacher. 'ubse0uent research by others, ins#ired by her boo$, #roduced results which showed e-#licit grammatical instruction in the mother language to be more #roductive. %hese develo#ments, cou#led with the emergence of humanist #edagogy led to a ra#id decline in the #o#ularity of audiolingualism. ;hili# 'mith2s study from 146511464, termed the ;ennsylvania ;ro&ect, #rovided significant #roof that audio1lingual methods were less effective than a more traditional cognitive a##roach involving the learner2s first language. Today ?es#ite being discredited as an effective teaching methodology in 14<0, audio1 lingualism continues to be used today, although it is ty#ically not used as the foundation of a course, but rather, has been relegated to use in individual lessons. As it continues to be used, it also continues to gain criticism, as 9eremy Harmer notes, GAudio1lingual methodology seems to banish all forms of language #rocessing that hel# students sort out new language information in their own minds.H As this ty#e of lesson is very teacher centered, it is a #o#ular methodology for both teachers and students, #erha#s for several reasons but in #articular, because the in#ut and out#ut is restricted and both #arties $now what to e-#ect. Manifestations in Popular Culture %he fact that audio1lingualism continues to manifest itself in the classroom is reflected in #o#ular culture. ilms often de#ict one of the most well1$nown as#ects of audio1lingualism C the re#etition drill. !n 'outh ;ar$ "#isode M1<5, +artman a##lies the re#etition drill while teaching a class of high school students. !n 3ad 3a- 1 ,eyond %hunderdome, an L; record of a rench Lesson instructs a #air of obliging children to 2re#eat2 short #hrases in rench and then in "nglish. +he oral approach./ituational language teaching %his a##roach was develo#ed from the 14:0s to the 1460s by ,ritish a##lied linguists such as Harold ;almer and A.'. Hornsby. %hey were familiar with the ?irect method as well as the wor$ of 14th century a##lied linguists such as .tto 9es#erson and ?aniel 9ones but attem#ted to develo# a scientifically1founded a##roach to teaching "nglish than was evidence by the ?irect 3ethod.N1O

A number of large1scale investigations about language learning and the increased em#hasis on reading s$ills in the 1450s led to the notion of (vocabulary control(. !t was discovered that languages have a core basic vocabulary of about 5,000 words that occurred fre0uently in written te-ts, and it was assumed that mastery of these would greatly aid reading com#rehension. ;arallel to this was the notion of (grammar control(, em#hasi@ing the sentence #atterns most1commonly found in s#o$en conversation. 'uch #atterns were incor#orated into dictionaries and handboo$s for students. %he #rinci#le difference between the oral a##roach and the direct method was that methods devised under this a##roach would have theoretical #rinci#les guiding the selection of content, gradation of difficulty of e-ercises and the #resentation of such material and e-ercises. %he main #ro#osed benefit was that such theoretically1based organi@ation of content would result in a less1confusing se0uence of learning events with better conte-tuali@ation of the vocabulary and grammatical #atterns #resented. Last but not least, all language #oints were to be #resented in (situations(. "m#hasis on this #oint led to the a##roach2s second name. 'uch learning in situ would lead to students2 ac0uiring good habits to be re#eated in their corres#onding situations. %eaching methods stress ;;; 6#resentation 6introduction of new material in conte-t8, #ractice 6a controlled #ractice #hase8 and #roduction 6activities designed for less1controlled #ractice88. Although this a##roach is all but un$nown among language teachers today, elements of it have had long lasting effects on language teaching, being the basis of many widely1used "nglish as a 'econdD oreign Language te-tboo$s as late as the 14*0s and elements of it still a##ear in current te-ts. 3any of the structural elements of this a##roach were called into 0uestion in the 1460s, causing modifications of this method that lead to +ommunicative language teaching. However, its em#hasis on oral #ractice, grammar and sentence #atterns still finds wides#read su##ort among language teachers and remains #o#ular in countries where foreign language syllbuses are still heavily based on grammar. 0unctional%notional Approach inocchiaro, 3. P ,rumfit, +. 614*:8. %he unctional1Botional A##roach. Bew Qor$, BQC .-ford =niversity ;ress. This method of language teaching is categori#ed along "ith others under the rubric of a communicati e approach. The method stresses a means of organi#ing a language syllabus. The emphasis is on breaking do"n the global concept of language into units of analysis in terms of communicati e situations in "hich they are used. A notional1functional syllabus is more a way of organi@ing a language learning curriculum than a method or an a##roach to teaching. !n a notional1functional syllabus, instruction is organi@ed not in terms of grammatical structure as had often been done with the AL3, but in terms of GnotionsH and Gfunctions.H !n this model, a GnotionH is a #articular conte-t in which #eo#le communicate, and a GfunctionH is a s#ecific #ur#ose for a s#ea$er in a given conte-t. As an e-am#le, the GnotionH or conte-t shopping re0uires numerous language functions including as$ing about #rices or features of a #roduct and bargaining. 'imilarly, the notion party would re0uire numerous functions li$e introductions and greetings and discussing interests and hobbies. ;ro#onents of the notional1functional syllabus claimed that it addressed the deficiencies they found in the AL3 by hel#ing students develo# their ability to effectively communicate in a variety of real1life conte-ts. %he use of #articular notions de#ends on three ma&or factorsC a. the functions b. the elements in the situation, and c. the to#ic being discussed. A situation may affect variations of language such as the use of dialects, the formality or informality of the language and the mode of e-#ression. 'ituation includes the following elementsC A. %he #ersons ta$ing #art in the s#eech act ,. %he #lace where the conversation occurs

+. %he time the s#eech act is ta$ing #lace ?. %he to#ic or activity that is being discussed 1-ponents are the language utterances or statements that stem from the function, the situation and the to#ic. 2ode is the shared language of a community of s#ea$ers. 2ode%switching is a change or switch in code during the s#eech act, which many theorists believe is #ur#oseful behavior to convey bonding, language #restige or other elements of inter#ersonal relations between the s#ea$ers. 0unctional 2ategories of Language 3ary inocchiaro 614*:, #. 651668 has #laced the functional categories under five headings as noted belowC personal! interpersonal! directi e! referential! and imaginati e. ,ersonal R +larifying or arranging oneKs ideas/ e-#ressing oneKs thoughts or feelingsC love, &oy, #leasure, ha##iness, sur#rise, li$es, satisfaction, disli$es, disa##ointment, distress, #ain, anger, anguish, fear, an-iety, sorrow, frustration, annoyance at missed o##ortunities, moral, intellectual and social concerns/ and the everyday feelings of hunger, thirst, fatigue, slee#iness, cold, or warmth Interpersonal 3 "nabling us to establish and maintain desirable social and wor$ing relationshi#sC "nabling us to establish and maintain desirable social and wor$ing relationshi#sC greetings and leave ta$ings introducing #eo#le to others identifying oneself to others e-#ressing &oy at anotherKs success e-#ressing concern for other #eo#leKs welfare e-tending and acce#ting invitations refusing invitations #olitely or ma$ing alternative arrangements ma$ing a##ointments for meetings brea$ing a##ointments #olitely and arranging another mutually convenient time a#ologi@ing e-cusing oneself and acce#ting e-cuses for not meeting commitments indicating agreement or disagreement interru#ting another s#ea$er #olitely changing an embarrassing sub&ect receiving visitors and #aying visits to others offering food or drin$s and acce#ting or declining #olitely sharing wishes, ho#es, desires, #roblems ma$ing #romises and committing oneself to some action com#limenting someone ma$ing e-cuses e-#ressing and ac$nowledging gratitude 4irective R Attem#ting to influence the actions of others/ acce#ting or refusing directionC ma$ing suggestions in which the s#ea$er is included ma$ing re0uests/ ma$ing suggestions refusing to acce#t a suggestion or a re0uest but offering an alternative #ersuading someone to change his #oint of view re0uesting and granting #ermission as$ing for hel# and res#onding to a #lea for hel# forbidding someone to do something/ issuing a command giving and res#onding to instructions warning someone discouraging someone from #ursuing a course of action establishing guidelines and deadlines for the com#letion of actions

as$ing for directions or instructions 5eferential R tal$ing or re#orting about things, actions, events, or #eo#le in the environment in the #ast or in the future/ tal$ing about language 6what is termed the metalinguistic functionC R tal$ing or re#orting about things, actions, events, or #eo#le in the environment in the #ast or in the future/ tal$ing about language 6what is termed the metalinguistic functionC identifying items or #eo#le in the classroom, the school the home, the community as$ing for a descri#tion of someone or something defining something or a language item or as$ing for a definition #ara#hrasing, summari@ing, or translating 6L1 to L5 or vice versa8 e-#laining or as$ing for e-#lanations of how something wor$s com#aring or contrasting things discussing #ossibilities, #robabilities, or ca#abilities of doing something re0uesting or re#orting facts about events or actions evaluating the results of an action or event Imaginative 3 ?iscussions involving elements of creativity and artistic e-#ression discussing a #oem, a story, a #iece of music, a #lay, a #ainting, a film, a %> #rogram, etc. e-#anding ideas suggested by other or by a #iece of literature or reading material creating rhymes, #oetry, stories or #lays recombining familiar dialogs or #assages creatively suggesting original beginnings or endings to dialogs or stories solving #roblems or mysteries

2ommunicative language teaching +ommunicative language teaching 6+L%8 is an a##roach to the teaching of languages that em#hasi@es interaction as both the means and the ultimate goal of learning a language. ?es#ite a number of criticisms, it continues to be #o#ular, #articularly in "uro#e, where constructivist views on language learning and education in general dominate academic discourse. !n recent years, %as$1based language learning 6%,LL8, also $nown as tas$1based language teaching 6%,L%8 or tas$1based instruction 6%,!8, has grown steadily in #o#ularity. %,LL is a further refinement of the +L% a##roach, em#hasi@ing the successful com#letion of tas$s as both the organi@ing feature and the basis for assessment of language instruction. +L% is an a##roach to the teaching of second and foreign languages that em#hasi@es interaction as both the means and the ultimate goal of learning a language. !t is also referred to as Gcommunicative a##roach to the teaching of foreign languagesH or sim#ly the G+ommunicative A##roachH. *elationship "ith other methods and approaches Historically, +L% has been seen as a res#onse to the Audio1Lingual 3ethod 6AL38, and as an e-tension or develo#ment of the Botional1 unctional 'yllabus. %as$1based language learning, a more recent refinement of +L%, has gained considerably in #o#ularity. +ritics of AL3 asserted that this over1em#hasis on re#etition and accuracy ultimately did not hel# students achieve communicative com#etence in the target language. Boam +homs$y argued (Language is not a habit structure. .rdinary linguistic behaviour characteristically involves innovation, formation of new sentences and #atterns in accordance with rules of great abstractness and intricacy(. %hey loo$ed for new ways to #resent and organi@e language instruction, and advocated the notional functional syllabus, and eventually +L% as the most effective way to teach second and foreign languages. However, audio1lingual methodology is still #revalent in many te-t boo$s and teaching materials. 3oreover, advocates of audio1lingual methods #oint to their success in im#roving as#ects of language that are habit driven, most notably #ronunciation. Overview of CLT

As an e-tension of the notional1functional syllabus, +L% also #laces great em#hasis on hel#ing students use the target language in a variety of conte-ts and #laces great em#hasis on learning language functions. =nli$e the AL3, its #rimary focus is on hel#ing learners create meaning rather than hel#ing them develo# #erfectly grammatical structures or ac0uire native1 li$e #ronunciation. %his means that successfully learning a foreign language is assessed in terms of how well learners have develo#ed their communicative com#etence, which can loosely be defined as their ability to a##ly $nowledge of both formal and sociolinguistic as#ects of a language with ade0uate #roficiency to communicate. +L% is usually characteri@ed as a broad approach to teaching, rather than as a teaching method with a clearly defined set of classroom #ractices. As such, it is most often defined as a list of general #rinci#les or features. .ne of the most recogni@ed of these lists is ?avid BunanKs 614418 five features of +L%C 1. An em#hasis on learning to communicate through interaction in the target language. 5. %he introduction of authentic te-ts into the learning situation. :. %he #rovision of o##ortunities for learners to focus, not only on language but also on the Learning 3anagement #rocess. 7. An enhancement of the learnerKs own #ersonal e-#eriences as im#ortant contributing elements to classroom learning. 5. An attem#t to lin$ classroom language learning with language activities outside the classroom. %hese five features are claimed by #ractitioners of +L% to show that they are very interested in the needs and desires of their learners as well as the connection between the language as it is taught in their class and as it used outside the classroom. =nder this broad umbrella definition, any teaching #ractice that hel#s students develo# their communicative com#etence in an authentic conte-t is deemed an acce#table and beneficial form of instruction. %hus, in the classroom +L% often ta$es the form of #air and grou# wor$ re0uiring negotiation and coo#eration between learners, fluency1based activities that encourage learners to develo# their confidence, role1#lays in which students #ractice and develo# language functions, as well as &udicious use of grammar and #ronunciation focused activities. 2lassroom activities used in 2L+ "-am#le Activities Eole ;lay !nterviews !nformation )a# )ames Language "-changes 'urveys ;air Wor$ Learning by teaching However, not all courses that utili@e the +ommunicative Language a##roach will restrict their activities solely to these. 'ome courses will have the students ta$e occasional grammar 0ui@@es, or #re#are at home using non1communicative drills, for instance. Critiques of CLT .ne of the most famous attac$s on +ommunicative Language teaching was offered by 3ichael 'wan in the "nglish Language %eaching 9ournal on 14*5N1O Henry Widdowson res#onded in defense of +L%, also in the "L% 9ournal 614*5 :46:8C15*11618. 3ore recently other writers 6e.g. ,a-N5O8 have criti0ued +L% for #aying insufficient attention to the conte-t in which teaching and learning ta$e #lace, though +L% has also been defended against this charge 6e.g. Harmer 500:N:O8. %he +ommunicative A##roach often seems to be inter#reted asC if the teacher understands the student we have good communication. What can ha##en though is that a teacher who is from the same region, understands the students when they ma$e errors resulting from first language

influence. .ne #roblem with this is that native s#ea$ers of the target language can have great difficulty understanding them. %his observation may call for new thin$ing on and ada#tation of the communicative a##roach. %he ada#ted communicative a##roach should be a simulation where the teacher #retends to understand only that what any regular s#ea$er of the target language would, and should react accordingly. N7O +as6%!ased language learning +as6%!ased language learning (+BLL), also $nown as +as6%!ased language teaching (+BL+) or +as6%!ased instruction (+BI) is a method of instruction in the field of language ac0uisition. !t focuses on the use of authentic language, and to students doing meaningful tas$s using the target language/ for e-am#le, visiting the doctor, conducting an interview, or calling customer services for hel#. Assessment is #rimarily based on tas$ outcome 6ieC the a##ro#riate com#letion of tas$s8 rather than sim#ly accuracy of language forms. %his ma$es %,LL es#ecially #o#ular for develo#ing target language fluency and student confidence. %,LL was #o#ulari@ed by B. ;rabhu while wor$ing in ,angalore, !ndia. ;rabhu figured out that his students could learn language &ust as easily with a non1linguistic #roblem as when they are concentrating on linguistic 0uestions. 9ane Willis bro$e it into three sections. %he #re1tas$, the tas$ cycle, and the language focus. In Practice %he core of the lesson is, as the name suggests, the tas$. All #arts of the language used are deem#hasi@ed during the activity itself, in order to get students to focus on the tas$. Although there may be several effective framewor$s for creating a tas$1based learning lesson, here is a rather com#rehensive one suggested by 9ane Willis. Bote that each lesson may be bro$en into several stages with some stages removed or others added as the instructor sees fit. Pre-tas !n the #re1tas$, the teacher will #resent what will be e-#ected of the students in the tas$ #hase. Additionally, the teacher may #rime the students with $ey vocabulary or grammatical constructs, although, in (#ure( tas$1based learning lessons, these will be #resented as suggestions and the students would be encouraged to use what they are comfortable with in order to com#lete the tas$. %he instructor may also #resent a model of the tas$ by either doing it themselves or by #resenting #icture, audio, or video demonstrating the tas$. Tas ?uring the tas$ #hase, the students #erform the tas$, ty#ically in small grou#s, although this is de#endent on the ty#e of activity. And unless the teacher #lays a #articular role in the tas$, then the teacher2s role is ty#ically limited to one of an observer or counselorJthus the reason for it being a more student1centered methodology. Plannin! Having com#leted the tas$, the students #re#are either a written or oral re#ort to #resent to the class. %he instructor ta$es 0uestions and otherwise sim#ly monitors the students. "eport %he students then #resent this information to the rest of the class. Here the teacher may #rovide written or oral feedbac$, as a##ro#riate, and the students observing may do the same. #nalysis Here the focus returns to the teacher who reviews what ha##ened in the tas$, in regards to language. !t may include language forms that the students were using, #roblems that students had, and #erha#s forms that need to be covered more or were not used enough. Practice %he #ractice stage may be used to cover material mentioned by the teacher in the analysis stage. !t is an o##ortunity for the teacher to em#hasi@e $ey language.

#$vanta!es %as$1based learning is advantageous to the student because it is more student1centered, allows for more meaningful communication, and often #rovides for #ractical e-tra1linguistic s$ill building. Although the teacher may #resent language in the #re1tas$, the students are ultimately free to use what grammar constructs and vocabulary they want. %his allows them to use all the language they $now and are learning, rather than &ust the 2target language2 of the lesson. urthermore, as the tas$s are li$ely to be familiar to the students 6egC visiting the doctor8, students are more li$ely to be engaged, which may further motivate them in their language learning. Disa$vanta!es %here have been criticisms that tas$1based learning is not a##ro#riate as the foundation of a class for beginning students. .thers claim that students are only e-#osed to certain forms of language, and are being neglected of others, such as discussion or debate. %eachers may want to $ee# these in mind when designing a tas$1based learning lesson #lan.N5O N7O Language immersion Language immersion is a method of teaching a second language 6also called L5, or the target language8. =nli$e a more traditional language course, where the target language is sim#ly the sub&ect material, language immersion uses the target language as a teaching tool, surrounding, or (immersing( students in the second language. !n1class activities, such as math, social studies, and history, and those outside of the class, such as meals or everyday tas$s, are all conducted in the target language. %oday2s immersion #rograms are based on those founded in the 1460s in +anada when middle1income "nglish1s#ea$ing #arents convinced educators to establish an e-#erimental rench immersion #rogram enabling their children 2to a##reciate the traditions and culture of rench1s#ea$ing +anadians as well as "nglish1s#ea$ing +anadians2. "ducators distinguish between language immersion #rograms and submersion. !n the former, the class is com#osed of students learning the L5 at the same level/ while in the latter, one or two students are learning the foreign language, which is the first language 6L18 for the rest of the class, thus they are (thrown into the ocean to learn how to swim( instead of gradually immersed in the new language. A new form of language related syllabus delivery called !nternationalised +urriculum has #rovided a different angle to the issue by immersing the curricula from various countries into the local language curriculum and se#arating out the language learning as#ects of the syllabus. ;ro#onents of this methodology believe immersion study of in a language foreign to the country of instruction doesn2t #roduce as effective results as se#arated language learning and may in fact, hinder educational effectiveness and learning in other sub&ect areas. Types A number of different immersion #rograms have evolved since those first ones in +anada. !mmersion #rograms may be categori@ed according to age and e%tent of immersion. #!e +arly immersionC students begin the second language from the age of 5 or 6. Middle immersionC students begin the second language from the age of 4 or 10. Late immersionC students begin the second language between the ages of 11 1 17. Extent !n total immersion, almost one hundred #ercent of class time is s#ent in the foreign language. 'ub&ect matter taught in foreign language and language learning #er se is incor#orated as necessary throughout the curriculum. %he goals are to become functionally #roficient in the foreign language, to master sub&ect content taught in the foreign languages, and to ac0uire an understanding of and a##reciation for other cultures. %his ty#e of #rogram is usually se0uential, cumulative, continuous, #roficiency1oriented, and #art of an integrated grade school se0uence. "ven in total immersion, the language of the curriculum may revert to the first language of the learners after several years.

!n partial immersion, about half of the class time is s#ent learning sub&ect matter in the foreign language. %he goals are to become functionally #roficient in the second language 6though to a lesser e-tent than through total immersion8, to master sub&ect content taught in the foreign languages, and to ac0uire an understanding of and a##reciation for other cultures. !n t"o-"ay immersion, also called (dual-( or (bilingual immersion(, the student #o#ulation consists of s#ea$ers of two or more different languages. !deally s#ea$ing, half of the class is made u# of native s#ea$ers of the ma&or language in the area 6i.e. "nglish in the =.'.8 and the other half is of the target language 6i.e. '#anish8. +lass time is s#lit in half and taught in the ma&or and target languages. %his way students encourage and teach each other, and eventually all become bilingual. %he goals are similar to the above #rogram. ?ifferent ratios of the target language to the native language may occur. !n content-based foreign languages in elementary schools 6 L"'8, about 15150S of class time is s#ent in the foreign language and time is s#ent learning #er se as well as learning sub&ect matter in the foreign language. %he goals of the #rogram are to ac0uire #roficiency in listening, s#ea$ing, reading, and writing the foreign language, to use sub&ect content as a vehicle for ac0uiring foreign language s$ills, and to ac0uire an understanding of and a##reciation for other cultures. !n ,L+- #rograms, five to fifteen #ercent of class time is s#ent in the foreign language and time is s#ent learning language #er se. !t ta$es a minimum of <5 minutes #er wee$, at least every other day. %he goals of the #rogram are to ac0uire #roficiency in listening and s#ea$ing 6degree of #roficiency varies with the #rogram8, to ac0uire an understanding of and a##reciation for other cultures, and to ac0uire some #roficiency in reading and writing 6em#hasis varies with the #rogram8. % !n ,L+. 6 oreign Language "-#erience8 #rograms, fre0uent and regular sessions over a short #eriod of time or short andDor infre0uent sessions over an e-tended #eriod of time are #rovided in the second language. +lass is usually almost always in the first language. .nly one to five #ercent of class time is s#ent sam#ling each of one or more languages andDor learning about language. %he goals of the #rogram are to develo# an interest in foreign languages for future language study, to learn basic words and #hrases in one or more foreign languages, to develo# careful listening s$ills, to develo# cultural awareness, and to develo# linguistic awareness. %his ty#e of #rogram is usually noncontinuous. Met%o$ quality ,a$er has found that more than one thousand studies have been com#leted on immersion #rograms and immersion language learners in +anada. %hese studies have given us a wealth of information. Across these studies, a number of im#ortant observations can be found. "arly immersion students lag !ehind their monolingual #eers in literacy 6reading, s#elling, and #unctuation8 for the first few years only. However, after the first few years, the immersion students catch u# with their #eers. !mmersion #rograms have no negative effects on s#o$en s$ills in the first language. "arly immersion students ac0uire almost1native1li$e #roficiency in #assive s$ills2 6listening and reading8 com#rehension of the second language by the age of 11. "arly immersion students are more successful in listening and reading #roficiency than #artial and late immersion students. !mmersion #rograms have no negative effects on the cognitive develo#ment of the students. 3onolingual #eers #erform better in sciences and math at an early age, however immersion students eventually catch u# with, and in some cases, out#erform their monolingual #eers.

Learning !y teaching

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

!n #rofessional education, learning !y teaching (7erman: LdL) designates a method that allows #u#ils and students to #re#are and to teach lessons, or #arts of lessons. Learning by teaching should not be confused with #resentations or lectures by students, as students not only convey a certain content, but also choose their own methods and didactic a##roaches in teaching classmates that sub&ect. Beither should it be confused with tutoring, because the teacher has intensive control of, and gives su##ort for, the learning #rocess in learning by teaching as against other methods. &istory 'eneca told in his letters to Lucilius that we are learning if we teach 6e#istulae morales !, <, *8C docendo discimus 6lat.C (by teaching we are learning(8. At all times in the history of schooling there have been #hases where students were mobili@ed to teach their #eers. re0uently, this was to reduce the number of teachers needed, so one teacher could instruct 500 students. However, since the end of the 14th century, a number of didactic1#edagogic reasons for student teaching have been #ut forward. 'tu$ents as teac%ers in or$er to spare teac%ers !n 1<45 the 'cotsman Andrew ,ellN1O wrote a boo$ about the mutual teaching method that he observed and used himself in 3adras. %he Londoner 9ose#h Lancaster #ic$ed u# this idea and im#lemented it in his schools. %his method was introduced 1*15 in rance in the (Acoles mutuelles(, because of the increasing number of students who had to be trained and the lac$ of teachers. After the rench revolution of 1*:0, 5,000 (Acoles mutuelles( were registered in rance. ?ue to a #olitical change in the rench administration, the number of Acoles mutuelles shran$ ra#idly and these schools were marginali@ed. !t is im#ortant to stress that the learning level in the ,ell1Lancaster1schools was very low. !n hindsight, the low level can #robably be attributed to the fact that the teaching1#rocess was delegated entirely to the tutors and that the teachers did not su#ervise and su##ort the teaching #rocess. 'tu$ents as teac%ers in or$er to improve t%e learnin!-process %he first attem#ts using the learning by teaching method in order to im#rove learning were started at the end of the 14th century. LdL as a comprehensi e method %he method received broader recognition starting in the early eighties, when 9ean1;ol 3artin develo#ed the conce#t systematically for the teaching of rench as a foreign language and gave it a theoretical bac$ground in numerous #ublications.N4O 14*< he founded a networ$ of more than a thousand teachers that em#loyed learning by teaching 6the s#ecifical nameC LdL R (Lernen durch Lehren(8 in many different sub&ects, documented its successes and a##roaches and #resented their findings in various teacher training sessions.N10O rom 5001 on LdL has gained more and more su##orters as a result of educational reform movements started throughout )ermany. Learnin! (y teac%in! (y Martin )L$L) LdL by 3artin consists of two com#onentsC a general anthro#ological one and a sub&ect1 related one. %he anthropological !asis of LdL is related to the #yramid or hierarchy of needs introduced by Abraham 3aslow, which consists, from base to #ea$, of 18 #hysiological needs, 58 safetyDsecurity, :8 socialDloveDbelonging, 78 esteemDself1confidence and 58 beingDgrowth through self1actuali@ation and self1transcendence. ;ersonal growth moves u#ward through hierarchy, whereas regressive forces tend to #ush downward. %he act of successful learning, #re#aration and teaching of others contributes to items : through 5 above. acing the #roblems of our world today and in the future, it is essential to mobili@e as many intellectual resources as #ossible, which ha##ens in LdL lessons in a s#ecial way. ?emocratic s$ills are #romoted through the communication and sociali@ation necessary for this shared discovery and construction of $nowledge.

%he su!8ect related component 6in foreign language teaching8 of LdL aims to negate the alleged contradiction between the three main com#onentsC automati@ation of s#eech1 related behavior, teaching of cognitively internali@ed contents and authentic interactionDcommunication. T%e L$L-approac% After intensive #re#aration by the teacher, students become res#onsible for their own learning and teaching. %he new material is divided into small units and student grou#s of not more than three #eo#le are formed. "ach grou# familiari@es itself with a strictly defined area of new material and gets the assignment to teach the whole grou# in this area. .ne im#ortant as#ect is that LdL should not be confused with a student1as1teacher1centered method. %he material should be wor$ed on didactically and methodologically 6im#ulses, social forms, summari@ing #hases etc.8. %he teaching students have to ma$e sure their audience has understood their messageDto#icDgrammar #oints and therefore use different means to do so 6e.g. short #hases of grou# or #artner e-ercises, com#rehension 0uestions, 0ui@@es etc.8. An im#ortant effect from LdL is to develo# the students websensibility. Building neural networ6: we!sensi!ility as target 3artin made first ste#s in order to transfer the brain structure 1 es#ecially the o#erating mode from neural networ$s 1 on the classroom1discourse N11O. %he conse0uences regarding the lessons phases and the differences to the other methods will be summed u# in the following overviewN15OC

,hases

/tudents' !ehavior All the students wor$ very intensively at home, because the 0uality of the classroom1discourse 6collective intelligence, emergence8 de#ends closely from the students 6(neurons(8 #re#aration. 'tudents who are not #re#ared or who often are absent are not able to react to im#ulses and to (fire off( im#ulses themselves

+eacher's !ehavior

4ifferences to other methods

,reparation and postprocessing at home

=sing LdL means that the lesson1time will not be used in order to %he teacher 6(frontal communicate new corte-(8 has to #erfectly contents but for master the contents interactions in little because he must be able groups or in the to intervene anytime plenum 6collective com#leting or giving $nowledge incentives in order to constructing8. %he enhance the classroom1 homewor$ has to discourse 0uality #re#are the students to interact on a high level during the lesson

Interactions during the lesson

%he teacher is loo$ing for absolute 0uietness %he students are sitting and concentration in circle. "ach student during the e-#lanations is listening very by students, so that concentrated to the each student may other students and as$s e-#lain their thoughts 0uestions if something without being disturbed in the e-#lanations is and so that other not clear students may as$ 0uestions to the student giving the lesson

=sing LdL means that during the #resentations and #lenum1interactions the students have to be a!solutely uiet so that everybody is able to listen the students utterances. ?uring the students interactions, the teacher has to !ac6 off

IntroductionC informations gathering two by twoC e-am#le (?om 9uan by 3oliTre(

=sing (human resources(C the students in charge of the course shortly #resent the new to#ic and let the other students discuss what is new about this to#ic 6for e-am#le about ?on 9iovanni by 3o@art8 %he leading students animate their classmates to interact 6they are sitting in circle8 as long as all the 0uestions are as$ed and cleared. %he students interact li$e neurones in neuronal networ$s and thoughts are (emerging(.

%he teacher is loo$ing if the students really e-change their $nowledge

=sing LdL means that the already e-isting students1$nowledge about the new to#ic will be inventoried in little grou#s

0irst deepeningC )athering informations in the class

%he teacher cares for the o##ortunity of each student to intervene, the teacher as$s 0uestions if something is not clear and has to be clarified by the class through interacting 6until the (emergence( has reach the eligible 0uality8 %he teacher is observing the communication and intervenes if something is not clear. %he teacher continues to let the students clarify what they have said if means or contents are not com#letely clear

%he previous 6nowledge from each student will be interchanged within the #lenum1classroom1 discourse and aligned, since the new contents will be fed in.

%he teaching students introduce the new contents divided in Introducing the little #ortions to their new contents in the #eers 6for instance classroom relevant scenes from 6e-am#leC ?om 9uan8 and they (3oliTres humor in as$ re#eatedly (om /uan(8 0uestions in order to test if everything is clear Led by the teaching students, the relevant +he second scenes will be #layed deepeningC ;laying and memori@ed 6for scenes e-am#le the seduction from the #easant1maid by ?on 9uan8 +he third deepeningC written house article 6te-t tas$, inter#retation of a #lace, for instance, ?on 9uan2s discussion with his father8

,y LdL the new contents are shared in little portions and communicated ste# by ste# in the classroom.

!n LdL the teacher is a %he teacher gives in#ut director and is not of new ideas, and cares afraid of interru#ting if for ade0uate and #lays in front of the successful scene1 other students are not #laying by the students e-#ressive enough 6wor6shop ambiance8.

All #u#ils wor$ hard at %he teacher collects all !n teaching younger home homewor$ and corrects years the LdL tas$s are it very e-actly #re#ared during the lessons themselves. or older years, the #re#aration shifts more and more towards homewor6 so that a bigger #ro#ortion of the teaching time is

available for interactions 6collective reflection8 . 3ost teachers using the method do not a##ly it in all their classes or all the time. %hey state the following advantages and disadvantagesC #$vanta!es* 'tudent wor$ is more motivated, efficient, active and intensive due to lowered inhibitions and an increased sense of #ur#ose ,y eliminating the class division of authoritative teacher and #assive audience, an emotive solidarity is obtained. 'tudents may #erform many routine tas$s, otherwise unnecessarily carried out by the instructor Be-t to sub&ect1related $nowledge students gain im#ortant $ey 0ualifications li$e 1 teamwor$ 1 #lanning abilities 1 reliability 1 #resentation and moderation s$ills 1 self1confidence Disa$vanta!es %he introduction of the method re0uires a lot of time. 'tudents and teachers have to wor$ more than usual. %here is a danger of sim#le du#lication, re#etition or monotony if the teacher does not #rovide #eriodic didactic im#etus. T%e Martin-reception 3artins Wor$ has been largely received in teacher training and by #racticing teachersC since 14*5 more than 100 teacher students in all sub&ects wrote their ending thesis about LdL. Also the education administration received both the theory and the #ractice of LdL 6vgl.3argret Eue# 1444N1:O8. !n didactics handboo$s LdL has been described as an (e%treme form of learner centred teaching(N17O8. .n the university level, LdL has been disseminated by 9oachim )r@ega in )ermany, )uido .ebel N15O in 9a#an and Alina Eachimova N16O in Eussia. Learnin! (y teac%in! outsi$e t%e L$L-context Psyc%olo!y of e$ucation .n the field of #sychology of education in )ermany A. Een$l did research about Learning by teaching almost without referring to 3artin. !n his #ublication 144< he briefly 0uoted 3artin but in his article from 5006 in the 0andbook of psychology of education he &ust 0uoted "nglish articles.N1<O "ventually he comes to following &udgmentC (*egarding Learning by teaching the publications sho"s partly ery euphoristic 1udgments about Learning by teaching (...). 2onsidering the empirical researches this statements must be estimated "ith caution. Learning by teaching may but doesn)t must "ork successfully.( And furtherC (Thus further researches ha e to consider abo e all the utterly important practical and theoretical 3uestion! "hich conditions ha e to be gi en in order to reach good results using Learning by teaching as teaching method.( "-actly this researches have been done since 14*5 by the team surrounding 9ean1;ol 3artin. 'u$(ury sc%ools 'udbury schools, since 146*, do not segregate students by age, so that students of any age are free to interact with students in other age grou#s. .ne effect of this age mi-ing is that a great deal of the teaching in the school is done by students. Here are some statements about Learning by teaching in the 'udbury 'chools N1*OC (4ids lo e to learn from other kids. ,irst of all! it)s often easier. The child teacher is closer than the adult to the students difficulties! ha ing gone through them some"hat more recently. The e%planations are usually simpler! better. There)s less pressure! less

1udgment. And there)s a huge incenti e to learn fast and "ell! to catch up "ith the mentor. 4ids also lo e to teach. It gi es them a sense of alue! of accomplishment. More important! it helps them get a better handle on the material as they teach5 they ha e to sort it out! get it straight. -o they struggle "ith the material until it)s crystal clear in their o"n heads! until it)s clear enough for their pupils to understand.6 Pupil-Team Learnin!* T%e Durrell 'tu$ies !n the 1450s ?r. ?onald ?. ?urrell and his colleagues at ,oston =niversity #ursued similar methods which they named ;u#il1%eam Learning. A year1long efficacy study in the schools of ?edham, 3assachusetts, was #ublished in the ,oston =niversity 9ournal of "ducation, >ol. 175, ?ecember, 1454, entitled (Ada#ting !nstruction to the Learning Beeds of +hildren in the !ntermediate )rades( in which one of the authors, Walter 9. 3cHugh, re#orted significant learning gains from the use of #u#il teams. T%e +y!tos y Connection !n the 14:0s Lev >ygots$y wrote e-tensively, in Eussian, on the #rofound connection between language and cognition, and in #articular oral language 6s#eech8 and learning. %he im#lication of >ygots$y2s observations for Learning by %eaching would a##ear to be direct and a#t. (%he one who does the tal$ing, does the learning( may best summari@e the #oint. An e-am#le of >ygots$yKs insights in #ractice is demonstrated by the following four1ste# thin$1 #air1share collaborative, team1learning techni0ueC 1 1 %he teacher #oses a 0uestion or an issue to the whole class 6using a white1board if available8 5 1 'tudents are given time to thin$ about the 0uestion : 1 'tudents discuss their thoughts with a #artner 7 1 "ach #air shares its thoughts with another #air, or with the whole class ;aired1discussion and grou# sharing are oral1language activities that heighten congnitive awareness 6i.e learning8 of the content. +he /ilent 9ay %he 'ilent Way is an a##roach to language teaching designed to enable students to become inde#endent, autonomous and res#onsible learners. !t is #art of a more general #edagogical a##roach to teaching and learning created by +aleb )attegno. !t is constructivist in nature, leading students to develo# their own conce#tual models of all the as#ects of the language. %he best way of achieving this is to hel# students to be e-#erimental learners. %he 'ilent Way allows this. %he 'ilent Way is a discovery learning a##roach, invented by +aleb )attegno in the 50s. !t is often considered to be one of the humanistic a##roaches. !t is called %he 'ilent Way because the teacher is usually silent, leaving room for the students to tal$ and e-#lore the language. %he main ob&ective of a teacher using the 'ilent Way is to o#timi@e the way students e-change their time for e-#erience. %his )attegno considered to be the basic #rinci#le behind all educationC (Living a life is changing time into e-#erience.( %he students are guided into using their inherent sense of what is coherent to develo# their own (inner criteria( of what is right in the new language. %hey are encouraged to use all their mental #owers to ma$e connections between sounds and meanings in the target language. !n a 'ilent Way class, the students e-#ress their thoughts and feelings about concrete situations created in the classroom by themselves or the teacher. T%eory .rigin of the 'ilent Way %he a##roach is called the 'ilent Way because the teacher remains mainly silent, to give students the s#ace they need to learn to tal$. !n this a##roach, it is assumed that the students2 #revious e-#erience of learning from their mother tongue will contribute to learning the new foreign language. %he ac0uisition of the mother tongue brings awareness of what language is and this is retained in second language learning. %he awareness of what language is includes the

use of non1verbal com#onents of language such as intonation, melody, breathing, inflection, the convention of writing, and the combinations of letters for different sounds. Eods, #ictures, ob&ects or situations are aids used for lin$ing sounds and meanings in the 'ilent Way. 1 +aleb )attegno based his whole #edagogical a##roach on several general observations which therefore underlie the 'ilent Way. 1 irstly, it is not because teachers teach that students learn. %herefore, if teachers want to $now what they should be doing in the classroom, they need to study learning and the learners, and there is no better #lace to underta$e such a study than on oneself as a learner. When )attegno studied himself as a learner, he realised that only awareness can be educated in humans. His a##roach is therefore based on #roducing awarenesses rather than #roviding $nowledge. 1 When he studied other learners, he saw them to be strong, inde#endent and gifted #eo#le who bring to their learning their intelligence, a will, a need to $now and a lifetime of success in mastering challenges more formidable than any found in a classroom. He saw this to be true whatever their age and even if they were #erceived to be educationally subnormal or #sychologically 2damaged2. or an account of )attegno wor$ing with such learners, see 9ohn +aldwell Holt 0o" 2hildren Learn. As a teacher, he saw that his way of being in the class and the activities he #ro#osed could either #romote this state of being or undermine it. 3any of the techni0ues used in 'ilent Way classes grew out of this understanding, including the style of correction, and the silence of the teacher 1though it should be said that a teacher can be silent without being mute. 'im#ly, the teacher never models and doesn2t give answers that students can find for themselves. 'econdly, language is often described as a tool for communication. While it may sometimes function this way, )attegno observed that this is much less common than we might imagine, since communication re0uires of s#ea$ers that they be sensitive to their audience and able to e-#ress their ideas ade0uately, and of listeners that they be willing to surrender to the message before res#onding. Wor$ing on this is largely outside the sco#e of a language classroom. .n the other hand, language is almost always a vehicle for e-#ression of thoughts and feelings, #erce#tions and o#inions, and these can be wor$ed on very effectively by students with their teacher. %hirdly, develo#ing criteria is im#ortant to )attegno2s a##roach. %o $now is to have develo#ed criteria for what is right or wrong, what is acce#table or inacce#table, ade0uate or inade0uate. ?evelo#ing criteria involves e-#loring the boundaries between the two. %his in turn means that ma$ing mista$es is an essential #art of learning. When teachers understand this because they have observed themselves living it in their own lives, they will #ro#erly view mista$es by students as 2gifts to the class2, in )attegno2s words. %his attitude towards mista$es frees the students to ma$e bolder and more systematic e-#lorations of how the new language functions. As this #rocess gathers #ace, the teacher2s role becomes less that of an initiator, and more that of a source of instant and #recise feedbac$ to students trying out the language. 1 A fourth element which determines what teachers do in a 'ilent Way class is the fact that $nowledge never s#ontaneously becomes $now1how. %his is obvious when one is learning to s$i or to #lay the #iano. !t is s$iing rather than learning the #hysics of turns or the chemistry of snow which ma$es one a s$ier. And this is &ust as true when one is learning a language. %he only way to create a ($now1how to s#ea$ the language( is to s#ea$ the language. Materials %he materials usually associated with 'ilent Way are in fact a set of tools which allow teachers to a##ly )attegno2s theory of learning and his #edagogical theory 1the subordination of teaching to learning1 in the field of foreign language teaching. %he tools invented by +aleb )attegno are not the only #ossible set of tools for teachers wor$ing in this field. .thers can and indeed have been invented by teachers doing research in this area. 'ound D color chart %his is a wall chart on which can be seen a certain number of rectangles of different colours #rinted on a blac$ bac$ground. "ach colour re#resents a #honeme

of the language being studied. ,y using a #ointer to touch a series of rectangles, the teacher, without saying anything himself, can get the students to #roduce any utterance in the language if they $now the corres#ondence between the colours and the sounds, even if they do not $now the language. idel %his is an e-#anded version of the 'oundD+olour chart. !t grou#s together all the #ossible s#ellings for each colour, thus for each #honeme. A set of colored +uisenaire rods or low level language classes, the teacher may use +uisenaire rods. %he rods allow the teacher to construct non ambiguous situations which are directly #erce#tible by all. %hey are easy to mani#ulate and can be used symbolically. A green rod standing on the table can also be 3r. )reen. %hey lend themselves as well to the construction of #lans of houses and furniture, towns and cities, stationsU 1 However, the most im#ortant as#ect of using the rods is certainly the fact that when a situation is created in front of the students, they $now what the language to be used will mean before the words are actually #roduced. ,or$ c%arts %hese are charts of the same dimensions as the 'oundD+olour chart and the idel on which are #rinted the functional words of the language, written in colour. .bviously, the colours are systemati@ed, so that any one colour always re#resents the same #honeme, whether it is on the 'oundD+olour chart, the idel or the word charts. 'ince the words are #rinted in colour, it is only necessary for someone to #oint to a word for the 6other8 students to be able to read it, say it and write it. A set of 10 wall #ictures %hese are designed to e-#and vocabulary for low level grou#s. %he #ointer %his is one of the most im#ortant instruments in the teacher2s arsenal because it allows teaching to be based consciously and deliberately on the mental #owers of the students. !t allows the teacher to lin$ colours, gra#hemes or words together whilst maintaining the e#hemeral 0uality of the language. !t is the students2 mental activity which maintains the different elements #resent within them and allows them to restitute what is being wor$ed on as a #honetic or linguistic unit having meaning. %hus, each of the tools associated with 'ilent Way #lays its #art in allowing the teacher to subordinate his teaching to the students2 learning. "ach tool e-ists in order to allow the teacher to wor$ in a #in1#ointed way on the students as they wor$ on the language. "ach e-ists for the e-#ress #ur#ose of allowing the teacher to wor$ on the students2 awareness in order to #roduce as many awarenesses as #ossible in the language being studied. %he tools corres#ond to the theory and stem directly from it. ,oo$s for studentsC A Thousand -entences, -hort 'assages, +ight Tales Classroom #ctivities Bo 'ilent Way lesson really resembles another, because the content de#ends on the $now1how (here and now( of learners who are (here and now.( A beginning or elementary lesson will start with wor$ing simultaneously on the basic elements of the languageC the sounds and #rosody of the language and on the construction of sentences. %he materials described above will be fre0uently used. At first, the teacher will #ro#ose situations for the students to res#ond to, but very 0uic$ly the students themselves will invent new situations using the rods but also events in the classroom and their own lives. A recurrent #attern in low level 'ilent Way classes is the initial creation of a clear and unambiguous situation using the rods. %his allows the students to wor$ on the challenge of finding ways 1as many as #ossible1 of e-#ressing the situation in the target language. %he teacher is active, #ro#osing small changes so that the students can #ractise the language generated, always scru#ulously res#ecting the reality of what they see. %hey ra#idly become more and more curious about the language and begin to e-#lore it actively, #ro#osing their own changes to find out whether they can say this or that, reinvesting what they have discovered in new sentences. %he teacher can then gradually hand over the res#onsibility for the content of the