Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mama

Uploaded by

Roberto Pineda0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views11 pagesStudy investigated the use of'mama' or similar sounds by!, infants less than six months of age. Most parents thought that the infant wanted some formof attention, but a minority thought it indicated hunger. The'MAMA' cry appears to promote attention-giving behaviour by parents and other caretakers.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentStudy investigated the use of'mama' or similar sounds by!, infants less than six months of age. Most parents thought that the infant wanted some formof attention, but a minority thought it indicated hunger. The'MAMA' cry appears to promote attention-giving behaviour by parents and other caretakers.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views11 pagesMama

Uploaded by

Roberto PinedaStudy investigated the use of'mama' or similar sounds by!, infants less than six months of age. Most parents thought that the infant wanted some formof attention, but a minority thought it indicated hunger. The'MAMA' cry appears to promote attention-giving behaviour by parents and other caretakers.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

J. Child Lang. z8 (zoo+), go6.

Printed in the United Kingdom

# zoo+ Cambridge University Press

NOTE

Parental reports of MAMA sounds in infants: an

exploratory study*

HERBERT I. GOLDMAN

Associate Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, Albert Einstein Medical School,

Bronx, New York

(Received +8 March +ggg. Revised zo March zooo)

\vs1n\1

This study investigated the use of mama or similar sounds (collectively

referred to as MAMA) by infants less than six months of age.

Parents were directed to listen for MAMA sounds and to note the

sounds made, the age of onset, whether the sounds appeared to be

directed to any person or persons and whether they appeared to have a

purpose. MAMA began at a mode of two months, range two weeks to

ve months, was usually part of a cry, and was always interpreted as a

wanting sound. Most parents thought that the infant wanted some

formof attention, but a minority thought it indicated hunger. Responses

to a Structured Response Protocol indicated that some infants uttering

MAMA were satised if a favourite caretaker approached and paid

attention to them while the remainder were satised if they were both

paid attention to and picked up. The MAMA cry appears to promote

attention-giving behaviour by parents and other caretakers.

1noii1o

The marked similarity of infant words for mother in languages has

been reported (Murdock, +gg.) Based on Murdocks ndings, the well-

known linguist Jakobson, who, as Ingram (+gg+) has noted, was unaware of

the earlier work of Gheorghov (+g++), attempted to explain the similarity of

infant words for mother as follows. Often the sucking activities of a child are

accompanied by a slight nasal murmur, the only phonation that can be

[*] I thank Lois Bloom for encouragement and for critiquing several versions of the

manuscript. I thank Joan Goldman for many helpful suggestions. I thank the parents for

their co-operation with the study. Sharon Katzenstein and Suzanne Riccobono assisted

with the collection of the data. Address for correspondence: Herbert I Goldman, +zo

Union Turnpike, New Hyde Park, New York ++oo, USA. e-mail : higoldman!aol.com;

tel : +6 jz8 z8zz; fax: +6 jz8 z8j.

g

ooii\

produced when the lips are pressed to the mothers breast or the feeding

bottle and the mouth is full. Later this phonatory response to nursing is

reproduced [the nasal murmur plus a labial release producing the sound

mama] at the mere sight of food and nally as an expression of

discontent and impatient longing for missing food or absent nurser and any

ungranted wish (Jakobson, +g6o:+jo).

Jakobsons statement suggests an onset of mama in the rst few months

of life. Jakobson presented no data of his own, but, to support his statement,

he referred to three papers in which are presented careful observations on the

early language development, starting at birth, of ve children. However in

none of these papers is any special attention paid to mama, and only one

noted mama in the rst few months of life. Smoczynski (+gj) reported

hearing mama at one month of age upon the infant arising in the morning,

which he interpreted as the infant demanding food. In the other two studies,

mama was rst heard at eight and nine months of age (Gregoire, +gj;

Leopold, +gjg.)

No study has ever reported the use of mama by a cohort of infants to

determine the age at which mama is rst heard and the circumstances

surrounding the appearance of this sound. The present study attempts to do

this.

i1ioi

Participants

An unselected sample of infants in the authors solo private pediatric

practice was enrolled. There were jg boys and j6 girls. English was the only

language spoken in the homes of z infants. In the remaining homes the

following languages were spoken in addition to varying amounts of English:

Spanish (8), Hindi (z), Italian (z), Russian (z), Hebrew (j), Ibo (+), Chinese.

(j), Spanish and Greek (+), and Spanish and Italian (+).

Procedure

The study design was inuenced by the results of pilot questionnaire and

interview studies which revealed that some parents hear their infant uttering

mama or a similar sound (collectively referred to as MAMA) as early as

one month of age, while most parents did not. However, some of the parents

who did not hear a MAMA sound prior to being asked, subsequently

reported that such a sound v\s present which they had been oblivious to. As

a result of these preliminary ndings, in the present study parents were

instructed to listen for MAMA sounds and to do this starting when the

baby was a few days old.

At the rst oce visit of newly born infants, at j+8 days of age, parents

(both parents were usually present at the rst oce visit) were told that the

g8

\\ soiis

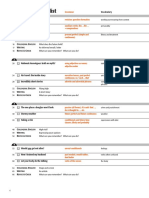

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

0;0 0;1 0;2 0;3 0;4 0;5

Age of onset of MAMA

Age

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

i

n

f

a

n

t

s

Fig. +. Age at which MAMA was rst heard.

author was attempting to study the MAMA sounds made by young infants

and their participation in this study was requested. All parents who were

asked agreed to participate. Parents were requested to listen for MAMA,

and, upon hearing such a sound, to note the age of the infant, the

circumstances (time of day, location of infant, location of parent, etc.),

whether the baby seemed to want something and if so what, and to whom, if

anyone, the sound appeared to be directed.

At each subsequent well-baby visit, at approximately monthly intervals,

until the age of six months, during the portion of the visit devoted to

assessing development, parents were asked if their infant had made a MAMA

sound since the previous well-baby visit. If so, they were questioned about

the age of the infant when this occurred, the circumstances etc., and their

replies were recorded. Parents were given sucient time to recall and recount

their observations. Emphasis was placed on MAMAs that occurred within a

few days of the visit. Babbled MAMAs, i.e. repetitive sounds reported as

being made without any emotion or apparent purpose other than making

sounds, were excluded by the author from the tabulated results.

Structured responses

Structured responses were carried out to help determine what it was the

MAMAuttering infant wanted, since there were some dierences in parental

interpretation of what the infant wanted in the rst z infants enrolled.

Consequently, in the group of the nal zj infants, parents of the +g who

gg

ooii\

uttered wanting MAMAs ( infants did not) were asked to administer a

Structured Response Protocol at the time a wanting MAMA occurred.

Printed instructions delineating the procedure and forms on which to record

the results were provided. In response to a wanting MAMA, parents were

instructed to act as follows.

+. Talk to the baby from wherever you are. If the baby is satised, i.e.

does not continue to cry, fuss or whine, the Structured Response is

completed. If not proceed to z.

z. Go near the baby. Do not look at or speak to the baby. If the baby is

not satised, proceed to j.

j. Look at and talk to the baby. If not satised, proceed to .

. Pick the baby up and pay attention to him or her. If not satised,

proceed to .

. Do whatever else you think might satisfy your baby.

nisii1s

MAMA sounds

MAMA was heard by parents of out of the infants enrolled in the

study. Figure + shows the age of onset, from two weeks to ve months with

a mode of two months. Table + presents parents descriptions of the sounds

1\vii +. Wanting MAMA : sounds and their frequency

Sounds made No. of infants

mama zj

ma +

mommy

ahmah j

mummum z

mmm z

mamamama z

mum +

nana +

meh +

ehmah +

mamama +

they heard; mama and ma were the most frequent, accounting for j of

the descriptions. At the time it was rst heard, j8 parents described the

MAMA sound as part of a cry; z parents described it as a pre-crying sound;

++ a whining sound; a call.

oo

\\ soiis

MAMA often occurred intermittently, rather than continuously, with

periods of weeks or months when it was not heard. During the latter part of

the six-month time period, the MAMA sound became more distinct and

more easily recognizable. It was described more often as a whine or call, less

often as a cry. It was more frequently directed only to the mother. Some

infants began to extend their arms forwards toward the caretaker in

association with MAMA, thereby asking to be picked up.

Twenty infants were not noted to make a MAMA sound during the rst

six months. At the end of this time period, parents of these infants were

questioned about their infants attention-seeking behaviour. Eighteen of

these zo infants had attention-seeking cries, whines or calls, containing an

eheh sound, 6 an ahah sound (both of these are possibly MAMA with no

lip closure), z dada, + lala, + heyhey and + ba.

To whom MAMA was addressed or whom the baby was seeking

In some cases to whom MAMA was addressed or whom the baby was

seeking could not be determined. However, it was sometimes possible to

come to a reasonable conclusion about this. For example, if the infant was

held by the father, and the MAMA cry, whine or call would stop if the

infant was given to the mother standing nearby, it was concluded that

MAMA had been addressed to the mother; or if the infant crying

MAMA was alone in the crib in his or her room, and would be satised if

picked up from the crib by the mother, father or grandmother, but not

satised if picked up by the grandfather, it was concluded that the baby had

been seeking the parents or the grandmother. Using these methods,

MAMA appeared to be directed to parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts

and even the family dog (Table z).

1\vii z. To whom MAMA was addressed or whom baby was seeking

To whom addressed or

whom baby was seeking No. of infants

Mother and father +

Mother only +j

Mother, father and two grandparents j

Mother and grandmother j

Mother, father and sibling z

Mother, father and grandmother z

Mother, grandfather and aunt +

Mother and aunt +

Mother and grandfather +

Mother, father and the dog +

o+

ooii\

1\vii j. What parents thought infants wanted when vocalizing MAMA

What parents thought

infants wanted No. of infants

To be picked up jz

Food g

Attention

Parent to return to room

To be cuddled

Change of caretaker j

To be taken out of the crib z

Change of position z

To be entertained z

To be taken out of infant seat z

Sleep +

To be walked +

To rewind the mobile +

To be taken out of the bath +

Total z*

* Some parents gave more than one interpretation.

1\vii . Results of 6 structured responses to MAMA (+glno. of

infants)

Structured response

Number of times

it was successful

(i.e. baby was satised)

+. Talking to baby from a distance o

z. Coming near to & ignoring baby o

j. Coming near to & talking to baby +

. Picking baby up & being attentive jo

Total *

* One infant was not satised by any part of the structured response.

Interpretation of MAMA

MAMA was always (\) interpreted as a wanting sound. Table j

shows the caretakers interpretations of what the baby wanted. The most

frequent interpretation, by far, was wanting to be picked up. Other types

of attention such as, to be cuddled, parent to return to room, change of

caretaker, attention, to be entertained etc., were alternative interpretations.

Some parents (g) initially thought that MAMA indicated hunger. At later

visits, ve indicated that, based upon further observation, they had changed

their minds and that MAMA was not and had not been a request for food.

The other four continued to believe that MAMA was a request for food,

but, when questioned, all four indicated that the infant would stop the

oz

\\ soiis

MAMA cry on being picked up inon to being fed, making the hunger

interpretation questionable. One of these mothers thought that her infant

stopped crying in this circumstance because he saw the bottle of milk in her

hands. It was suggested that she pick her baby up without a bottle in her

hands. To her surprise the MAMA cry stopped and the baby seemed

satised. This mother experimented further and found that she could stop

the MAMA cry without picking her baby up if she put her face in front of

the babys face and talked to him.

Structured response

In order to provide additional information on what the infant who was

uttering MAMA wanted, the administration of one or more Structured

Response Protocols was carried out on the last +g infants enrolled who

uttered a MAMA sound (a total of 6 Structured Responses, a range of +

per infant). Table presents the results. In instances the infants were

satised if they were spoken to up close or were picked up by an attentive

mother, suggesting that it is this that the infant wanted. In the 6th instance,

the infant was not satised by any part of the Structured Response or by

being fed, given a pacier, changed, walked or anything else the mother tried

and only stopped crying after + minutes. This mother thought that the

Structured Response had upset her baby and made him angry.

One mother, on her own initiative, in response to a MAMA cry, picked

her baby up but ignored himand found that he was not satised. Subsequent

to this, the nal four mothers carrying out Structured Responses were

requested to rst ignore the baby after picking him up, before paying any

attention to him. In each case the infant was not satised when he was picked

up and ignored, suggesting that it is primarily the attention of a favourite

caretaker that the infant wants, though some infants prefer that this attention

be given while they are held.

isisso

The results of the present study must be considered preliminary as they are

based on interviews with parents of their observations. These observations

were carried out in a prospective manner according to directions provided by

the study. To conrm and amplify these ndings, it will be desirable to

record and analyse these sounds while, at the same time, observing the

infants facial and body movements as well as the parental reaction.

Keller &Scholmerich (+g8) studied the vocalizations of infants during the

age period two to eighteen weeks. Crying and whining were both considered

to be negative vocalizations, as were sighing, fussing and sounds of dis-

comfort. (Most parents in the present study described MAMA as a cry or

whine.) In the Keller & Scholmerich study, infant negative vocalizations led

to: +. Changes in parental tactile behaviour (either beginning to touch the

oj

ooii\

baby or withdrawing a touch or touching a dierent part of the baby); z.

Changes in parent vestibular behaviour (initiation or cessation of parent

movement, change in tempo of movement, or a dierent kind of movement);

j. Parental vocalization. In the present study MAMA was most often

interpreted as a request for the parent to go to (vestibular behaviour) and pick

the baby up (tactile behaviour). No data were collected on how many parents

spoke to their infant at this time.

Many types of infant cries have been described, including hunger (Brennan

& Kirkland, +go, +g8z, +g8; Gladding, +g8; Seitamo & Wasz-Hockert,

+g8+; Freeburg & Lippman, +g86; Fuller & Horii, +g86, +g88; Ginsberg &

Kilbourne, +g88), birth and pleasure (Brennan & Kirkland, +go, +g8z,

+g8), pain (same as hunger, plus Grunau & Craig, +g8; Zeskind, +g8;

Zeskind &Marshall, +g88), fussy ( Fuller &Horii, +g86, +g88), and tired and

angry (Freeburg & Lippman, +g86).

Malatesta (+g8+) has analysed the cry literature (prior to +g8+) to

determine the reliability of the discrimination between dierent types of cries

by both mechanical and human analysis and concluded that, except for the

very young infant, during the rst days of life, dierent types of cries

representing dierent aective and motivational states can be somewhat

reliably discriminated by acoustic properties and also by human listeners.

Malatesta has further concluded that the early patterns of infant vocal

emotional expression are probably biogenetically determined and that there

may be certain universal vocal signals. Our results suggest that MAMA

may be one such signal.

The vocalizations of the very young infant have been described as

vegetative and reexive, but, by the second month, coos and goos appear

(Menn & Stoel-Gammon, +gg8). These are happy sounds, often ac-

companied by eye contact and smiles (Lenenberg, Rebelsky & Nicholas,

+g6) and therefore appear to be social in nature. MAMA, appearing at a

similar age is similarly social, calling for the attention of a favourite caretaker.

The study of DOdorico (+g8) is of considerable interest with regard to

the present investigation. Four infants were followed from o; o; 8.

Recordings were made of infant sounds while the experimenter or mother

played with the infant with and without a toy, and while the infant was alone

with a toy. Three types of sound categories were described discomfort,

request and call. The call sound occurred when the infant was alone and had

lost interest in the toy and, the experimenter concluded, was looking for and

calling his or her mother. Spectrographic analysis revealed that this pattern

of sounds was, for each infant, specic to the situation. In many respects,

therefore, this call cry is similar to the MAMA cry. Future study should

help clarify whether they are identical.

The articulation of MAMA changes as the infant ages, becoming clearer

and more easily recognizable as the infant reaches o; 6 or older. Major

o

\\ soiis

changes in the anatomy of the vocal tract take place during this time frame

(Kent & Miolo, +gg8) and are likely part of the reason for the change in the

sound.

If conrmed, our results would indicate that, at the early age of o;z, a

pattern of behaviour develops, often, but not always, accompanied by a

MAMA sound, which promotes attention giving behaviour on the part of

the parent or caretaker; attention that is important for the infants de-

velopment.

REFERENCES

Brennan, M. &Kirkland, J. (+go). Discrimination of infants cry-signals. Perceptual -Motor-

Skills q8, 68j6.

Brennan, M. & Kirkland, J. (+g8z). Classication of infant cries using descriptive scales.

Infant Behaviour and Development j, j+6.

Brennan, M. & Kirkland, J. (+g8). Comparison of perceptual dimensions uncovered from

infant cry-signals using the method of pair-comparisons and the semantic dierential.

Scandinavian Journal of Psychology z6, +zzo.

DOdorico, L. (+g8). Non-segmental features in prelinguistic communications an analysis

of some types of infant cry and non-cry vocalizations. Journal of Child Language 11, +z.

Freeburg, T. & Lippman, M. (+g86). Factors aecting discrimination of infant cries. Journal

of Child Language 1j, j+j.

Fuller, B. F. & Horii, Y. (+g86). Dierences in fundamental frequency, jitter and Shimmer

among four types of infant vocalizations. Journal of Communication Disorders 1q, +.

Fuller, B. F. & Horii, Y. (+g88). Spectral energy distribution in four types of infant

vocalizations. Journal of Communication Disorders z1, z66+.

Gheorghov, I. (+g++). Le developpement du langage chez linfant. In Premier Congres

International de Pedologie (Vol. z, pp. zo+8). Brussels: Librarie Misch & Thron.

Ginsburg, G. P. & Kilbourne, B. K. (+g88). Emergence of vocal alternation in motherinfant

exchanges. Journal of Child Language 1j, zz+j.

Gladding, S. T. (+g8). Empathy, gender, and training, as factors in the identication of

infants cry-signals. Perceptual-Motor-Skills q, z6o.

Gregoire, A. (+gj). LApprentisage du langage. Lie' ge: Faculte! de Philosophie et Lettres de

lUniversite! de Lie' ge.

Grunau, R. V. & Craig, K. D. (+g8). Pain expression in neonates facial expression and cry.

Pain z8, jg+o.

Ingram, D. (+gg+). An historical observation on Why Mama and Papa ?. Journal of

Child Language 18, +++j.

Jakobson, R. (+g6o). Why Mama and Papa ?. In B. Kaplan & S. Wapner (eds),

Perspectives in Psychological Theory. New York: International Universities Press.

Keller, H. A. & Scholmerich, A. (+g8). Infant vocalizations and parental reaction during

the rst months of life. Developmental Psychology zj (+), 6z.

Kent, R. D. & Miolo, G. (+gg8). Phonetic abilities in the rst year of life. In P. Fletcher &

B. MacWhinney (eds), The Handbook of Child Language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lenenberg, E. H., Rebelsky, F. G. & Nicholas, L. A. (+g6). The vocalizations of children

born to deaf and hearing parents. Human Development 8, zjj.

Leopold, W. F. (+gjg). Speech development of a bilingual child. Vocabulary growth in the rst

two years. Evanston & Chicago: Northwestern University.

Malatesta, C. Z. (+g8+). Infant emotion and the vocal aect lexicon. Motivation and Emotion

j, +zj.

Menn, L. & Stoel-Gammon, L. (+gg8). Phonological development. In P. Fletcher & B.

MacWhinney (eds), The handbook of child language. Oxford: Blackwell.

Murdock, G. P. (+gg). Cross-linguistic parallels in parental kin terms. Anthropological

Linguistics 1, +.

o

ooii\

Seitamo, L. & Wasz-Hockert, O. (+g8+). Early motherchild relationships in the light of

infant cry studies. Acta Paedopsychiatrica q, z+zz.

Smoczynski, P. (+gj). Przyswajanie przez dziecko podstaw systemu jezykowego. Societas

Scientarum Lodziensis 1q, +.

Zeskind, P. S. (+g8). Adult heart rate responses to infants cry sounds. British Journal of

Developmental Psychology j, jg.

Zeskind, P. S. &Marshall, T. R. (+g88). The relation between variation in pitch and maternal

perception of infant crying. Child Development jq, +gj6.

o6

Reproducedwith permission of thecopyright owner. Further reproductionprohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Jack 2014 PDFDocument6 pagesJack 2014 PDFRoberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- Protein Interactors of The Cellular Tumor Antigen p53 With Response To Ionizing RadiationDocument2 pagesProtein Interactors of The Cellular Tumor Antigen p53 With Response To Ionizing RadiationRoberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- Advanced Chemistryprize2013Document12 pagesAdvanced Chemistryprize2013Roberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- Time From Quantum Entanglement: An Experimental IllustrationDocument7 pagesTime From Quantum Entanglement: An Experimental IllustrationRoberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- Automated Reasoning in Higher-Order Logic Using The TPTP THF InfrastructureDocument27 pagesAutomated Reasoning in Higher-Order Logic Using The TPTP THF InfrastructureRoberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- SocNet TheoryAppDocument116 pagesSocNet TheoryAppJosesio Jose Jose Josesio100% (2)

- Menu Restaurante Eye TrackingDocument28 pagesMenu Restaurante Eye TrackingRoberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- Brain Myths: EditorialDocument1 pageBrain Myths: EditorialRoberto PinedaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Passive VoiceDocument5 pagesPassive VoiceBritanny MadaguezNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Orthodox Christian MissionDocument7 pagesIndigenous Orthodox Christian MissionMichael E. Malulani K. OdegaardNo ratings yet

- 2nd Grade Decodables - Unit 1Document11 pages2nd Grade Decodables - Unit 1pqr1No ratings yet

- Performative Utterances: July 2013Document35 pagesPerformative Utterances: July 2013Bryan M. PalayaNo ratings yet

- NEF 4th Edition - 5 - Upper IntermediateDocument4 pagesNEF 4th Edition - 5 - Upper IntermediateIsadora LottNo ratings yet

- Horseshit: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesHorseshit: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediawalteryNo ratings yet

- Project BrightsDocument6 pagesProject BrightsAlthea SantosNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Isyarat Satera Jontal Dalam PengeDocument10 pagesBahasa Isyarat Satera Jontal Dalam Pengeputrimutiaa11No ratings yet

- AssignmentsDocument3 pagesAssignmentssabrina's worldNo ratings yet

- Module in PurposiveCommunication Chapter 1 2Document26 pagesModule in PurposiveCommunication Chapter 1 2Zachary Miguel PeterNo ratings yet

- TensesDocument49 pagesTensesPepy_GumilarNo ratings yet

- Irony in The Mayor of Casterbridge A Literary Pragmatic StudyDocument12 pagesIrony in The Mayor of Casterbridge A Literary Pragmatic StudyMuhammad AdekNo ratings yet

- Past ContinuousDocument2 pagesPast Continuousaroman_No ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT 1 - Technical or Non-TechnicalDocument2 pagesASSIGNMENT 1 - Technical or Non-TechnicalAlthea DumabokNo ratings yet

- What Is A SyllableDocument1 pageWhat Is A SyllableManish ThakurNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument164 pagesPDFmardia100% (1)

- Culturally Relevant Supplement Rubric-For TeachersDocument1 pageCulturally Relevant Supplement Rubric-For Teachersapi-170235603No ratings yet

- Latin For The New Millennium. Teacher's Manual, Ch. 1 (Level 3) (Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers) - Milena Minkova, Terence Tunberg (2010)Document16 pagesLatin For The New Millennium. Teacher's Manual, Ch. 1 (Level 3) (Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers) - Milena Minkova, Terence Tunberg (2010)A KNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 Subject and Verb Agreement by T. OpulenciaDocument23 pagesGrade 6 Subject and Verb Agreement by T. OpulenciaKaye NodgnalahNo ratings yet

- Figurative Language PDFDocument3 pagesFigurative Language PDFLuz Mayores AsaytunoNo ratings yet

- Unit 11 PDFDocument6 pagesUnit 11 PDFCamilo EspitiaNo ratings yet

- U1 S1 Trabajo Individual 01Document3 pagesU1 S1 Trabajo Individual 01Luis MurgaNo ratings yet

- Branches of LinguisticsDocument2 pagesBranches of LinguisticsAiman AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Curs 6 Ing-ComplementsDocument10 pagesCurs 6 Ing-ComplementsGabriela Pauna100% (1)

- Nunan 1988 Syllabus DesignDocument171 pagesNunan 1988 Syllabus DesignMasoudTabatabaeeNo ratings yet

- Word Classes PDFDocument15 pagesWord Classes PDFAnonymous XX45Jp0% (3)

- Voice and DictionDocument13 pagesVoice and DictionAira NadineNo ratings yet

- Future Perfect and Future Perfect Continuous - WorksheetDocument2 pagesFuture Perfect and Future Perfect Continuous - WorksheetMadalena PedrosoNo ratings yet

- Is There Are ThereDocument3 pagesIs There Are ThereAkmaral MyrzagalievaNo ratings yet

- Karen Lahousse, Stefania Marzo - Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2012 - Selected Papers From 'Going Romance' Leuven 2012 (2014, John Benjamins Publishing Company)Document262 pagesKaren Lahousse, Stefania Marzo - Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2012 - Selected Papers From 'Going Romance' Leuven 2012 (2014, John Benjamins Publishing Company)Ana Cristina SilvaNo ratings yet