Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Known Unknowns of RTI

Uploaded by

Abhishek GuptaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Known Unknowns of RTI

Uploaded by

Abhishek GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

PERSPECTIVES

june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 32

Known Unknowns of RTI

Legitimate Exemptions or

Conscious Secrecy?

Pankaj K P Shreyaskar

Views are personal.

Pankaj K P Shreyaskar (shreyaskarps@gmail.

com) is with the Central Information

Commission, Government of India, New Delhi.

After almost more than eight

years of the Right to Information

Act being in force, the process of

accessing information still faces

impediments. The ow of

information is restricted either

due to various public institutions

not coming within the ambit of

the Act or the information being

exempt under various clauses of

the Act. This article examines

select judgments/orders of the

Central Information Commission

and the superior courts exhibits

to show how the exemption

clauses have been utilised to

camouage the disclosure norms

including that of negating the

applicability of RTI by several

organisations. It also presents the

contingency model for the RTI

Act, 2005.

Whats wrong with open government? Why

shouldnt the public know more about whats

going on?

My dear boy, its a contradiction in terms.

You can be open, or you can have government.

But surely the citizens of a democracy have a

right to know?

No They have a right to be ignorant. Knowl-

edge only means complicity and guilt, igno-

rance has a certain dignity.

1

S

ir Humphreys preachment about

knowledge and ignorance pro-

vides me with enough motivation

to investigate its veracity in the light of

the Right to Information (RTI) Act. The

Act has been enacted

to provide for setting out the practical re-

gime of right to information for citizens to

secure access to information under the con-

trol of public authorities, in order to promote

transparency and accountability in the

working of every public authority, the con-

stitution of a Central Information Commis-

sion and State Information Commissions

and for matters connected therewith or inci-

dental thereto (RTI Act 2005).

2

Further the RTI Act, 2005 envisages

And whereas revelation of information in ac-

tual practice is likely to conict with other

public interests including efcient operations

of the Governments, optimum use of limited

scal resources and the preservation of con-

dentiality of sensitive information; And

whereas it is necessary to harmonise these

conicting interests while preserving the par-

amountcy of the democratic ideal (ibid).

3

It is in the name of preserving the con-

dentiality of information and the para-

mountcy of the democratic ideals that

the organisations have advocated the

exem ption clauses vociferously and stra-

tegically, in some cases.

Prashant Sharma (2012) in his thesis

observes that

The RTI Act has been widely hailed as a land-

mark piece of legislation both within and

beyond the country, primarily for three rea-

sons. First, the fact of enacting a right to

i nformation law is a radical departure from

the access to information regime that existed

prior to the enactment of this law. Previous-

ly, under the Ofcial Secrets Act (OSA) of

1923, all information held by public authori-

ties was considered secret by default, unless

the government itself deemed it otherwise.

The second reason is the specic nature of

the Act it is generally considered to be a

very strong one within the context of access

to information laws anywhere in the world,

and is considered to be a transformatory

piece of legislation which is fundamentally

altering the citizen-state relationship in the

country. Finally, the narrative describing the

process leading to the enactment of this Act

traces it to a grassroots struggle, which

locates the vocabulary and the represen-

tation of the RTI discourse within a frame-

work of real and meaningful democracy

with respect to both the process and its

outcome.

4

The OSA 1923 was enacted by the Bri-

tish to keep the ruled away from the

r uler in India. T S R Subramanian in The

New Indian Express (29 April 2013) notes

Despite wide-ranging changes in the situa-

tion since then, particularly after Independ-

ence, the regimen, of marking les as Con-

dential, Secret, or Top Secret, has rem-

ained by and large unchanged. Indeed the

attempt made in 1997 to dilute the rigours of

the Ofcial Secrets Act fell by the wayside,

suffering the same fate as so many other

attempted reforms, due to system inertia.

Meanwhile the Right to Information Act,

which, not by coincidence also originated

from 1997, brought in the concept of trans-

parency and openness in government prac-

tices and procedures.

5

The popular belief is that the path-

breaking RTI Act has tremendous poten-

tial to bring about necessary systemic

reforms in the functioning of public

organisations. However, this potential

cannot be realised effectively, unless

there is support through other systemic

reforms.

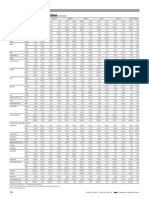

Contingency Model

Let us understand the existing schemes

of the rights and disclosure of informa-

tion in the RTI Act through the contin-

gency model (Figure 1, p 33). I have fol-

lowed the contingency model of trans-

parency mechanisms for services to

e xhibit the contingencies as envisaged

in the Act.

6

A citizen is entitled to enforce his/her

right to ask for information only from a

PERSPECTIVES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 33

A citizen has no right

to information

Figure 1: The Contingency Model of Right to Information Act, 2005

Citizens of India

to exercise their

right to

information

Is the organisation,

a public authority

u/s 2 (h)?

Is the organisation exempt

u/s 24?

Is the information

held by the public

authority?

Can the public authority

access the information

under any other law?

A citizen has no

right to information

A citizen has no right

to information

Do the rights subjected

to exemption clauses

of section 8?

Has there been allegation(s)

of violation of human rights

argued?

Has an allegation of

corruption argued?

Do the rights subjected

to exemption clauses of

Section 8?

Whether CIC/SIC

authorised disclosure

in matters of violation

of human rights?

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

No

public authority as dened in Section

2(h) and not from bodies that are not

public authorities.

Justice Sanjiv Khanna in the National

Stock Exchange of India Limited vs Cen-

tral Information Commission and Ors

noted that

Section 2(h) of the Act consists of two parts.

The rst part states that public authority

means any authority or body or institution of

self-government established or constituted

by or under the Constitution, by any enact-

ment made by the Parliament or the State

Legislature or by a notication issued or or-

der made by the appropriate Government.

The second part starts from the word in-

cludes and states the term public authority

includes bodies which are owned, controlled

or substantially nanced directly or indi-

rectly by funds provided by the appropriate

Government and non-Government organisa-

tions substantially nanced directly or indi-

rectly by the funds provided by the appropri-

ate Government.

7

If a public authority can access infor-

mation from a private body under any

other law for the time being in force, it

shall be obliged to consider an applica-

tion for disclosure of this information, if

sought for under the RTI Act. In other

words, if some information about a pri-

vate sector bank can be accessed by the

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) under the

RBI Act, 1935 or the Banking Regulations

Act, 1949, the information seeker would

be entitled to get this information from

the RBI. The Supreme Court in Aditya

Bandopadhyay and Ors observed that

Certain safeguards have been built into the

Act so that the revelation of information will

not conict with other public interests which

include efcient operation of the govern-

ments, optimum use of limited scal re-

sources and preservation of condential and

sensitive information. The RTI Act provides

access to information held by or under the

control of public authorities and not in re-

gard to information held by any private per-

son. The Act provides the following exclu-

sions by way of exemptions and exceptions

(under sections 8, 9 and 24) in regard to

information held by public authorities:

(i) Exclusion of the Act in entirety under

section 24 to intelligence and security or-

ganisations specied in the Second Sched-

ule even though they may be public author-

ities (except in regard to information with

reference to allegations of corruption and

human rights violations.

8

(ii) Exemption of the several categories of

information enumerated in section 8(1) of

the Act which no public authority is under

an obligation to give to any citizen, not-

withstanding anything contained in the

Act [however, in regard to the information

exempted under clauses (d) and (e), the

competent authority, and in regard to the

information excluded under clause (j),

Central Public Information Ofcer/State

Public Information Ofcer/the Appellate

Authority, may direct disclosure of infor-

mation, if larger public interest warrants or

justies the disclosure].

9

(iii) If any request for providing access to

information involves an infringement of a

copyright subsisting in a person other than

the State, the Central/State Public Infor-

mation Ofcer may reject the request under

section 9 of RTI Act.

10

The proviso to Section 24(1) of the RTI

Act deals with the disclosure of informa-

tion in respect of allegations of violation

of human rights; the information shall

only be provided after the approval of

the Central Information Commission

(CIC) or the State Information Commis-

sion (SIC) as the case may be.

Section 8(1) deals with exemption

from disclosure of information and some

of them are encapsulated in one of the

judgments in UOI vs Central Information

Commission and Ors of the Delhi HC. It

has noted that

Section 8(1) of the RTI Act begins with a non-

obstante clause and stipulates that notwith-

standing any other provision under the RTI

Act, information need not be furnished

when any of the clauses (a) to (j) apply.

Right to information is subject to exceptions

or exclusions stated in section 8(1) (a) to

(j) of the RTI Act. Sub-clauses (a) to (j) are

in the nature of alternative or independent

sub clauses. Section 8(1)(e) protects infor-

mation available to a person in his duciary

relationship. As per Section 3(42) of the

General Clauses Act, 1897 the term person

includes a juristic person, any company or

association or body of individuals, whether

incorporated or not. Section 8(1)(e) adum-

brates that information should be available

to a person in his duciary relationship. The

person in Section 8(1)(e) will include the

public authority. The word available used

in this Clause will include information held

by or under control of a public authority and

also information to which the public author-

ity has access to under any other statute or

law. The sub-clause 8 (1) (i) protects Cabinet

papers including records of deliberations of

the Council of Ministers, Secretaries and

other ofcers. The rst proviso however stip-

ulates that the prohibition in respect of the

decision of the Council of Ministers, the rea-

sons thereof and the material on the basis of

which decisions were taken shall be made

public after the decision is taken and the

matter is complete or over.

11

PERSPECTIVES

june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 34

A division bench of the Delhi HC in

Supreme Court of India vs Subhash Chan-

dra Agarwal observed that

the conict between the right to personal

privacy and the public interest in the disclo-

sure of personal information was recognised

by the legislature by exempting purely per-

sonal information under Section 8(1)(j) of

the Act. Section 8(1)(j) says that disclosure

may be refused if the request pertains to

personal information the disclosure of which

has no relationship to any public activity or

interest, or which would cause unwarranted

invasion of the privacy of the individual.

Thus, personal information including tax

r eturns, medical records etc. cannot be dis-

closed in view of Section 8(1)(j) of the Act. If,

however, the applicant can show sufcient

public interest in disclosure, the bar (pre-

venting disclosure) is lifted and after duly

notifying the third party (i e, the individual

concerned with the information or whose

records are sought) and after considering his

views, the authority can disclose it.

12

Section 9 provides that without preju-

dice to the provisions of Section 8, a re-

quest for information may be rejected if

such a request for providing access

would involve an infringement of copy-

right. Sections 10 and 11 are the proce-

dural aspects of dealing with disclosure

of information in relation to severability

and third parties.

The following section presents the

status of disclosure of information in

some of the public authorities/organisa-

tions consequent upon decisions of the

CIC and/or superior courts. Some of the

decisions of the CIC, where the disclo-

sure norms or principles have been laid

down have been stayed in the superior

courts and the fate of RTI applications in

such organisations/sectors are in limbo.

In other cases the decision of the CIC it-

self negates the disclosure. Further, this

section also presents some incidents

wherein the public authorities denied

the disclosure on frivolous grounds.

Status of Disclosure

The CIC while adjudicating on an appeal

in the matter of Sarbajit Roy vs Delhi

Electricity Regulation Commission, Delhi

(2006) declared that

Both from the point of view of their being

created by a government notication and

the nances received directly or indirectly

from Government of NCT of Delhi, DISCOMs

are public authorities within the meaning of

Right to Information Act and, because the

matter was raised in appeal before us and

has been closely argued in this hearing they

are so declared by this Commission in the

present proceedings. The DISCOMs will how-

ever proceed to set up the necessary infra-

structure for servicing applications under

the RTI Act, 2005, to be fully operational

within sixty days from the date of issue of

this decision.

13

The matter was challenged through a

civil writ petition (CWP) No 544/2007

before the Delhi HC by the BSES Rajdhani

Power Limited (BRPL), one of the electri-

city distribution companies of Delhi and

since then the issue of applicability of

RTI in the DISCOMS is under stay. The

Delhi HC in its order 30 January 2013

o bserved that

issue raised in the petition before them is a

common issue pertaining to the determina-

tion of the question as to whether the peti-

tioner falls within the denition of a public

authority as contained in the RTI Act, 2005.

Interim orders to continue.

The plight of the information seekers

in any of the DISCOMS of Delhi at present

is in limbo. When they approach the

public information ofcers (PIOS) of the

DISCOMS, a response stating the position

of the pendency of the writ (supra) is

conveyed to them. The CIC also disposes

all matters arising from the responses of

any of the agencies of DISCOMS by reiter-

ating its earlier stand. The information

seeker has no option but to keep out

from the disclosure regimes in relation

to the functioning of DISCOMS in Delhi.

The CIC while adjudicating on an

appeal in a certain matter pronounced

that

Every authority or institution which is a

state has to be a public authority under Sec-

tion 2(h) of the Right to Information Act,

2005. Even a non-governmental organiza-

tion if substantially nanced directly or indi-

rectly by funds provided by the Government

may be a public authority. Even a private

institution substantially nanced by an ap-

propriate Government can also be a public

authority but such non-governmental bod-

ies or such private institutions or bodies may

not be categorised as state but they would

be public authorities within the meaning of

Section 2(h) of the RTI Act. There is enough

merit in these submissions and the Commis-

sion agrees that an authority or an institu-

tion or a body if it is a state within the

meaning of Article 12 of the Constitution of

India, it cannot claim that it is outside the

purview of the Right to Information Act,

2005.

14

The single bench of the Delhi HC

while dismissing the CWP No 4748/2007

aga inst the impugned order of the CIC

held that

Some arguments were addressed on the

question whether the Central Government

owns National Stock Exchange in view of

the shareholding pattern. SEBI in their

counter afdavit has stated that more than

50% of the shares of the petitioner stock ex-

changes are owned by Government of India

or government companies. The petitioner is

a public authority as it is an auth ority or in-

stitution of self-government constituted or

established by notication or order issued by

the appropriate Government. It is also held

that the petitioner is controlled by the appro-

priate Government.

15

The petitioners moved a letters patent

appeal (LPA) before the Delhi HC. They

argued that it is neither a government

body nor nanced by the government

and therefore they are not within the

ambit of RTI Act. A division bench of the

Delhi HC held that there will be a stay

of operation of the impugned order of

the single bench as well as the order of

the CIC dated 7 June 2007.

16

Therefore, at the time of writing this

article no information is being disclosed

by the stock exchanges and no RTI re-

gime is in position. However, the hyper-

link About Us of the NSE website says

that The Exchange has brought about

unparalleled transparency, speed and

efciency, safety and market integrity. It

has set up facilities that serve as a model

for the securities industry in terms of

systems, practices and procedures.

17

It

is difcult to understand how an organi-

sation can claim to have brought about

unparalleled transparency when it is

playing truant as far as the RTI Act is

concerned.

In another case, an appellant Veena

Sikri of Jorbagh, New Delhi submitted

applications under the Act to the central

public information ofcers (CPIOS) of the

prime ministers ofce (PMO), the cabi-

net secretariat, department of personnel

and training (DOPT) and the Ministry of

External Affairs (MEA) requesting ac-

cess/inspection to/of documents and

les regarding rules, principles and

rationale governing the selection and

appointment of the foreign secretary.

PERSPECTIVES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 35

The CIC while adjudicating on an appeal

in the matter of Veena Sikri vs DoPT,

PMO, MEA and Cabinet Secretariat

held that

There is no doubt that information collated

during selection may include some person-

al information the disclosure of which may

cause invasion of privacy of other individu-

als who have not been eventually selected.

Moreover, these individuals are not party

to the present appeal. But then the informa-

tion can still be made available by applying

the doctrine of severability enshrined in

section 10 of the RTI Act, as mentioned in

our decision quoted above. Government

can, in that case, allow access to informa-

tion as requested by appellant by providing

access to that part of the record which does

not contain any i nformation which is ex-

empt from dis closure under the Act and

which can be reasonably severed from any

part that contains exempt information, in

due accordance with section 10 of the Act.

Information which concerns other individ-

uals and which will cause unwarranted in-

vasion to the privacy of such individual

cannot be subjected to disclosure. On the

other hand, it is for the concerned compe-

tent authority to still allow access to this

information if it were satised that the

larger public interest justied disclosure of

such information. But in this case, the com-

petent authority has clearly decided other-

wise. The Commission, therefore, has a

duty to see as to whether disclosure is pos-

sible without causing unwarranted inva-

sion of privacy of other candidates who

were considered and not selected and, if so

whether such disclosure will necessitate

application of procedure prescribed under

Section 11(1) as the information is or may

concern third parties. In view of this and in

light of the ruling of the Apex Court cited at

the conclusion of para 20 above, the Com-

mission will examine the le and accord-

ingly, we call upon the concerned public

authority which in this case is the Cabinet

Secretariat to produce all relevant docu-

ments from the initiation to the culmi-

nation of the process of appointment of

F oreign Secretary.

18

The impugned order of the commis-

sion was challenged through the CWP

in the Delhi HC. The court had stayed

the order of the commission. The pro-

cess and rationale of making appoint-

ments of a diplomat to the senior

most position in India thus remains

out of bounds for a citizen under the

RTI Act.

The CIC while adjudicating on an ap-

peal in the matter of Kuldip Nayar, Ex-

MP vs Ministry of Defence (MoD) regarding

disclosure of the Henderson-Brooks

r eport on the China-India War in 1962

held that

There is no doubt that the issue of the India-

China Border particularly along the north-

east parts of India is still a live issue with

ongoing negotiations between the two coun-

tries on this matter. The disclosure of infor-

mation of which the Henderson Brooks re-

port carries considerable detail on what pre-

cipitated the war of 1962 between India and

China will seriously compromise both secu-

rity and the relationship between India and

China, thus having a bearing both on inter-

nal and external security.

19

On the other hand Nayar argued that

the subject is 43 years old and should

have been available in the archives of

India, some 30 years after the report

was submitted to the government.

The representatives of the MoD ar-

gued before the commission that

the report prepared by Lt Gen Henderson

Brooks and Brig Prem Bhagat was a part of

internal review conducted on the orders of

the then Chief of Army Staff Gen Choud-

hary. Reports of internal review are not even

submitted to government, let alone placed in

the public domain.

20

Madbhushi Sridhar in his article

Ofcial Secrecy Power vs Citizens

A ccess Right observed that

Neville Maxwell in 2001 has already di-

vulged details of how things went wrong in

1962. CIC might have taken a right decision

because of internal and external security of

India is linked with certain sensitive aspect

of the Report. Still those parts including the

reasons for not submitting the report to the

government should be brought to the notice

of the public by the CIC.

21

The commission in yet another matter

of Sandeep Unnithan vs Integrated HQ,

Ministry of Defence (Navy) (2007)

wherein one of the members of the

bench was the chief information com-

missioner, as he then was (also a mem-

ber in the Kuldip Nayar case (supra))

argued

that armed forces of free, democratic na-

tions should have a proper disclosure of vital

information policy especially in respect of

events connected with engagement of our

armed forces with the forces of other coun-

tries in theatres of war. Such voluntarily dis-

closed information, of course without com-

promising national security, saves unneces-

sary speculation about the causes and ef-

fects of an event. It also saves the armed

forces the odium of attempting to hide fail-

ures behind excessive secrecy an odium,

which in fact may be wholly undeserved. A

rational disclosure policy refurbishes the im-

age of the armed forces and only helps en-

hance condence in their capability in the

eyes of the people of the country whose se-

curity, it is the forces duty to ensure. All

great armed forces of the world voluntarily

give out information about their successes as

well as their failures and are none the worse

for it. Most information about the sinking of

the British Navys Warship H M S Shefeld

during Falkland War (1982) stands fully dis-

closed. While we have no observations to

make on the assertion of Admiral Cheema

that because compliance of the two Navies

are completely different, the readiness of the

Royal Navy to disclose information on the

Falkland War is not replicable in India, we

still nd that having no further information

than has been admitted to be held by the In-

dian Navy on a disaster of the magnitude of

the sinking of INS Khukri, on the basis of res-

cue operation regarding which Navy person-

nel have been honoured with awards is inad-

equate and will not only impair healthy self

criticism, it will prevent authentic recording

of the history of the Indian Navy for future

generations.

22

The bench of the commission thus

r ecommended that the Indian Navy and,

in fact the Indian armed forces should

build up their storehouse of information,

as mandated under Section 4(1) of the

RTI Act, 2005 for disclosure at the appro-

priate time for benet of students of

Indias defence and to enhance the peo-

ples trust in the armed forces undoubted

capacity to ensure national security.

It is relevant to mention here that

the UK government has very recently

decided that government les from

1983 would be the rst records to be

declassied under the new 20-year

rule which means that ofcial papers

will be made public sooner. The Right

to Information Act, 2007 of Nepal, un-

der Sections 27 (2) and (4) provides for

a mechanism regarding classication

of the government records in terms of

the years that they may be kept con-

dential. In India, Section 8 (3) of the

RTI Act requires the public authority to

provide the information sought for

u nder Section 6 of the Act subject to

the provisions of the clauses of (a), (c)

and (i) of sub-section (1) of Section 8, if

the event has occurred 20 years before the

date on which any request is made under

this Act. However, any institutional

PERSPECTIVES

june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 36

a rrangements in the public ofces to

ensure this are not in place.

The CIC while adjudicating on an

appeal in the matter of R K Jain vs

Depar tment of Revenue (2012), wherein

the disclosure of notications 12/2012

Customs was prayed for, directed the

public authority to produce the le be-

fore the commission so that it can satisfy

itself as to whether the requested docu-

ments are a part of the budget-making

process and whether disclosure thereof

would adversely affect the economic in-

terests of the state. The representative of

the department of revenue informed the

commission that

the competent authority has decided not to

produce these documents before it. The

Commission obser ved that without the scru-

tiny of these documents it was not possible

for the bench to decide the matter one way

or the other, it directed the registry to put up

the matter before the another bench.

23

Section 18(4) of the Act empowers the

CIC to examine any record to which this

Act applies and which is under the con-

trol of the public authority. No such

record may be withheld from it on any

grounds. Further, as per Section 19(7) of

the Act, the decision of the commission

is binding. The public authorities are

d uty-bound to comply with the decision

of the commission unless the decision is

legitimately negated. In the present case

however, the Tax Research Unit (TRU),

the department of nance decided not

to produce the documents called for

without getting any stay against the

impugned order of the CIC from the

superior courts. This kind of attitude

displayed by a public authority will only

serve to attenuate the RTI Act in the

years to come.

The full bench order of the commis-

sion (15 November 2010), under Section

19(8) (a), directed public authorities to

ensure compliance of suo motu disclo-

sures as laid down in Section 4, within a

stipulated time. While adjudicating in

the matter the CIC noted that

it has now become necessary that the top

echelons of the public authorities are

sensitised about seriously addressing the

several aspects of discharging their Sec-

tion 4 commitments, including progressive

digitisation of data and use of other available

technologies, to not only make transparency

the hallmark of their functioning, but also

to create the right conditions for the public

to access the information through painless

and efcient processes that shall be put

in place.

24

It further noted that

Transparency has not become such a good

idea because of the presence of the RTI Act,

but it is good because transparency pro-

motes good governance. Of the records,

documents and les held by public authori-

ties, a very large part can be made available

for inspection, or be disclosed on request to

the citizens, without any detriment to the in-

terest of the public authority. This has not

been done, or has still not been systemati-

cally addressed, largely because of an intui-

tive acceptance of secrecy as the general

norm of the functioning of public authori-

ties. This mental barrier needs to be crossed,

not so much through talks and proclamation

of adherence to openness in governance, but

through tangible action small things,

which cumulatively promote an atmosphere

of openness.

25

The commission directed the public

authorities to ensure compliance with

Section 4 obligations by uploading them

on a portal set-up exclusively for this

purpose by the CIC, to designate one of

their senior ofcers as Transparency

Ofcer (TO) (with all necessary sup-

porting personnel), whose task will be to

oversee the implementation of the Sec-

tion 4 obligation by public authorities,

and to apprise the top management

of its progress and to help promote

congenial conditions for positive and

timely response to RTI-requests by

CPIOS, deemed-CPIOS.

This order of the commission may be

termed as an avant-garde for ensuring

maximum disclosure through efcient

means. For the rst time suo motu dis-

closure of all the public authorities

would be available at one place. This

would be extremely useful for monitor-

ing not only the quality of the suo motu

disclosures but also the defaulters. The

order was welcomed by all the stake-

holders. The CIC provided a portal where

each of the public authorities could pro-

vide a link of their suo motu disclosures.

This would be the rst time that a senior

ofcer would be designated as TO,

accountable for reporting compliance

of the suo motu disclosure by the public

authorities.

The impugned order of the commis-

sion was challenged before the Delhi HC

REVIEW OF RURAL AFFAIRS

December 28, 2013

Decomposing Variability in Agricultural Prices:

The Case of Selected Indian Agricultural Commodities Ashutosh Kumar Tripathi

Direct Cash Transfer System for Fertilisers:

Why It Might be Hard to Implement Avinash Kishore, K V Praveen, Devesh Roy

Punjab Water Syndrome: Diagnostics and Prescriptions Himanshu Kulkarni, Mihir Shah

Sorghum and Pearl Millet Economy of India: N Nagaraj, G Basavaraj, P Parthasarathy Rao,

Future Outlook and Options Cynthia Bantilan, Surajit Haldar

Women at the Crossroads: Implementation of Employment

Guarantee Scheme in Rural Tamil Nadu Grace Carswell, Geert De Neve

Agricultural and Livelihood Vulnerability Reduction Tashina Esteves, K V Rao, Bhaskar Sinha,

through the MGNREGA S S Roy, Bhaskar Rao, Shashidharkumar Jha,

Ajay Bhan Singh, Patil Vishal, Sharma Nitasha,

Shashanka Rao, Murthy I K, Rajeev Sharma,

Ilona Porsche, Basu K, N H Ravindranath

For copies write to:

Circulation Manager,

Economic and Political Weekly,

320-321, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg,

Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013.

email: circulation@epw.in

PERSPECTIVES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 37

after a year and half of its pronounce-

ment. Union of India, the petitioner ar-

gued before the HC that the Commis-

sion has passed this order without hav-

ing any jurisdiction in the matter (2012).

It was also argued that the CIC cannot

direct the public authorities to designate

a TO as has been done in the impugned

order. The operation of the impugned

order has been stayed.

26

The CIC while adjudicating on an

appeal in the matter of Chandrachur

Ghose vs Ministry of Home Affairs re-

garding disclosure of the exhibits listed

in Appendix II of the report of the Justice

Mukherjee Commission of Inquiry on

the alleged disappearance of Netaji

Subhas Chandra Bose. The commission

held that

With regard to the information sought, MHA

is indeed the nodal Ministry in that it holds

custody. It is for this Ministry to decide as to

the application of exemption from disclosure

u/s 8(1). If as a matter of courtesy the Minis-

try wishes to refer the issue of disclosure to

the originating departments under the OM

described in the hearing, it is, of course, up

to the discretion of the Mini stry of Home

Affairs so to do which is also compliance

with the OM. Nevertheless, exemption from

disclosure cannot be sought on grounds oth-

er than mentioned in any of the sub sections

of Sec 8(1). In this case, in the response, or

lack of it, of other public authorities from

which clearance has been sought, not one of

them has raised an objection citing any of

the above mentioned sub-sections. More-

over, sub sec (3) of Section 8 is clear in that it

calls for disclosure of any information relat-

ing to any occurrence, event or matter which

has taken place or occurred or happened

twenty years before the date of any request

is made u/s 6, providing only that this will

not apply to exemption under clauses (a), (c)

and (i) of sub sec (1), the application of none

of which has been pleaded in the present

case. Under the circumstances, the orders of

Ministry of Home Affairs withholding part

of the information sought are set aside.

27

The joint secretary, representing the

home ministry during the hearing be-

fore the CIC had stated that the minis-

try had no problem in disclosing the

documents pertaining to it, but it was

not possible to provide papers of other

ministries, PMO and some State govern-

ments mentioned in the report as they

wanted their records back.

28

This was an extremely surprising

stand taken by the MHA that it could not

provide documents since the state gov-

ernments and other central ministries

were demanding them back!

This examination of rulings and or-

ders will not be complete without men-

tioning the decision of the CIC regarding

the applicability of the RTI Act in the

case of political parties in Subhash

Chandra Agarwal and Anil Bairwal vs

AICC and others (2011). The decision of

the CIC in the political parties (supra)

case is a laudable one for it can be a sig-

nicant beginning towards ensuring

electoral transparency in India. The

commission held that the

INC, BJP, CPI(M), CPI, NCP and BSP have been

substantially nanced by the Central Gov-

ernment under section 2(h)(ii) of the RTI

Act. The criticality of the role being played

by these Political Parties in our democratic

set up and the nature of duties performed by

them also point towards their public charac-

ter, bringing them in the ambit of section

2(h). The constitutional and legal provisions

discussed herein above also point towards

their character as public authorities.

29

It directed the Presidents, General/

Secretaries of these Political Parties to

designate CPIOS and the Appellate

Authorities at their headquarters in 06

weeks time. It further observed that the

CPIOs so appointed will respond to the

RTI applications extracted in this order

in 04 weeks time.

30

It also directed that

besides, the Presidents/General Secre-

taries of the above mentioned Political

Parties they are to comply with the pro-

visions of section 4(1) (b) of the RTI Act

by way of making voluntary disclosures

on the subjects mentioned in the said

clause.

31

The DOPT vide its condential note

(already in public domain at http://

persmin.gov.in) of 23 July 2013 pro-

posed amendment of the RTI Act. It

reads as under:

The Right to Information Act, 2005 shall be

amended as below:

(A) Amendment of Section 2 by adding

explanation to the denition of Public

Authority in clause (h):

In Section 2 of the Right to Information Act,

2005 (hereinafter referred to as the princi-

pal Act), in clause (h), the following Expla-

nation shall be inserted, namely:-

Explanation The expression authority or

body or institution of self-government estab-

lished or constituted by any law made by

Parliament shall not include any association

or body of individuals registered or recog-

nised as political party under the Represen-

tation of the People Act, 1951.

(B) Insertion of new section 32 to give over-

riding effect:

After section 31 of the principal Act, the fol-

lowing section shall be inserted, namely:-

32. Notwithstanding anything contained in

any judgment, decree or order of any court

or commission, the provisions of this Act, as

amended by the Right to Information

(Amendment) Act, 2013, shall have effect

and shall be deemed always to have effect,

in the case of any association or body of indi-

viduals registered or recognised as political

party under the Representation of the Peo-

ple Act, 1951 or any other law for the time

being in force and the rules made or notica-

tions issued there under.

This Act shall be deemed to have come into

force on the 3rd day of June, 2013.

32

The fate of operation of the judgment

of the commission (supra) is pending the

outcome of the recommendation of the

Parliamentary Standing Committee for

the purpose.

There are several references that may

be analysed. However, I wish to con-

clude my arguments on the basis of the

analyses of the cases referred to above.

Conclusions

The RTI Act echoes the homily of James

Medison who said, A people who mean

to be their own governors must arm

themselves with power that knowledge

gives. It goes without saying that the

RTI has done great service to the nation

by empowering citizens to access infor-

mation without being subjected to pro-

vide reasons for seeking the informa-

tion. A large class of information is now

accessible due to the Act. However, this

may be sufcient only to provide a sense

of satisfaction to the information seekers

but is surely not adequate to bring in sys-

temic reforms which the complex gov-

ernance space requires. On the one

hand, the credit for unearthing several

modern day scams goes to the RTI but

perhaps the Act alone may not preclude

the occurrence of similar events in

f uture. The march from darkness of se-

crecy to dawn of transparency cannot be

completed without the support of many

other reforms.

The number of cases analysed above

for proving or rejecting my hypothesis

PERSPECTIVES

june 14, 2014 vol xlIX no 24 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 38

may not be signicant but the veracity

and the magnitude that the cases thrust

upon us gives me sufcient reasons to

believe that the conscious mindset of the

public authorities is set on holding on to

secrecy in their functioning through the

legitimate exemptions under the RTI Act.

The mindset of the public authorities

which is clouded by suspicion and secre-

cy needs to undergo a change to ensure

any form of transparency in India.

Notes

1 Conversation between Bernard Woolley, pri-

vate secretary to the minister for administra-

tive affairs, Sir Arnold Robinson, cabinet secre-

tary, and Sir Humphrey Appleby, permanent

secretary at the department of administrative

affairs, in the episode titled Open Govern-

ment in the iconic BBC television series of the

1980s, Yes Minister.

2 Excerpts from the preamble to RTI Act, 2005.

3 Ibid.

4 Sharma (2012).

5 Subramanian (2013).

6 Lindsay and Lodge (2001).

7 National Stock Exchange of India Limited

vs Central Information Commission & Others,

WP (C) 4748/2007, High Court of Delhi at New

Delhi.

8 Central Board of Secondary Education & Anr vs

Aditya Bandopadhyay & Ors, CIVIL APPEAL

NO 6454 OF 2011 [Arising out of SLP [C]

No 7526/2009], Supreme Court of India at

New Delhi.

Review of Womens Studies

April 26, 2014

Gender in Contemporary Kerala J Devika

Becoming Society: An Interview with Seleena Prakkanam J Devika

Struggling against Gendered Precarity in Kathikudam, Kerala Parvathy Binoy

Attukal Pongala: Youth Clubs, Neighbourhood: Groups and Masculine Performance of Religiosity Darshana Sreedhar

You Are Woman: Arguments with Normative Femininities in Recent Malayalam Cinema Aneeta Rajendran

Shifting Paradigms: Gender and Sexuality Debates in Kerala Muraleedharan Tharayil

Child Marriage in Late Travancore: Religion, Modernity and Change Anna Lindberg

Home-Based Work and Issues of Gender and Space Neethi P

For copies write to:

Circulation Manager,

Economic and Political Weekly,

320-321, A to Z Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg,

Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013.

email: circulation@epw.in

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 UOI vs Central Information Commission &

Ors, Writ Petition (Civil) Nos 8369/2009,

16907/2006, 4788/2008, 9914/2009, 6085/

2008, 7304/2007, 7930/2009 and 3607 of

2007, High Court of Delhi at New Delhi.

12 Supreme Court of India vs Subhash Chandra

Agarwal, LPA 501/2009, High Court of Delhi at

New Delhi.

13 Sarbajit Roy vs Delhi Electricity Regulatory Com-

mission, Delhi, appeal No CIC/WB/A/2006/

00011, CIC at New Delhi.

14 Raj Kumari Agarwal and others and National

Stock Exchange (NSE), Jaipur Stock Exchange

(JSE), Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI)

and Others, Appeal Nos CIC/AT/A/ 2006/00684

& CIC/AT/A/2007/00106, CIC at New Delhi.

15 National Stock Exchange of India Ltd vs

C entral Information Commission and Ors,

CWP No 748/2007, High court of Delhi at

New Delhi.

16 National Stock Exchange of India Ltd vs Central

Information Commission and Ors, LPA

315/2010, High Court of Delhi at New Delhi.

17 National Stock Exchange, About Us, http://

www.nseindia.com/global/content/about_us/

about_us.htm (acce ssed on 5 October 2013).

18 Veena Sikri vs DoPT, PMO, MEA & Ors, CIC/

WB/A/2007/00287, CIC at New Delhi.

19 Kuldip Nayar, Ex MP vs Ministry of Defence

(MoD), appeal No CIC/WB/C/2007/00500,

CIC at New Delhi.

20 Ibid.

21 Madabhushi Sridhar, Ofcial Secrecy Power

vs Citizens Access Rights, India Current

A ffairs, 3 September 2010, http://indiacurren-

taffairs.org/ofcial-secrecy-power-vs-citizens-

access-right-professor-madabhushi-sridhar/

(accessed on 8 October 2013).

22 Sandeep Unnithan vs Integrated HQ, Ministry of

Defence (Navy), Appeal No CIC/WB/A/ 2007/

01192, CIC at New Delhi.

23 R K Jain vs Department of Revenue, Appeal Nos

CIC/SS/A/2012/003663/LS,CIC/SS/A/2012/

003664/LS and CIC/SS/A/2012/003665/LS, CIC

at New Delhi.

24 Case No CIC/AT/D/10/000111, CIC at New Delhi.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Chandrachur Ghose vs Ministry of Home Affairs,

Appeal No CIC/WB/A/2009/000537, CIC at

New Delhi.

28 Ibid.

29 Subhash Chandra Agarwal & Anil Bairwal vs

AICC and Others, Appeal No CIC/SM/C/

2011/001386 and CIC/SM/C/2011/ 000838,

CIC at New Delhi.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Extracts from Cabinet Note No 1/13/2013-IR,

Department of Personnel & Training< Cabi-

net Note, last modied 23 July 2013, accessed

on 6 October 2013, http://ccis.nic.in/WriteRe-

adData/CircularPortal/D2/D02rti/1_13_2013-

IR.pdf

References

Sharma, Prashant (2012): The Right to Infor-

mation in India: The Turbid World of Transpar-

ency Reforms (PhD dissertation, LSE).

Subramanian, T S R (2013): National Security vs

Right to Know, The New Indian Express, Morn-

ing edition, sec Voices, 29 April, http://newin-

dianexpress.com/magazine/voices/arti-

cle390689.ece (accessed on 7 October 2013).

Stirton, Lindsay and Martin Lodge (2001): Contin-

gency Model of Effects of Transparency Mecha-

nisms for Services of Different Cost-Proles,

Journal of Law and Society, Vol 28, No 4 (De-

cember 2001), pp 471-89.

You might also like

- 1597628133-Right-To-Information AmendmentDocument6 pages1597628133-Right-To-Information AmendmentAshkar ChandraNo ratings yet

- A Layman’s Guide to The Right to Information Act, 2005From EverandA Layman’s Guide to The Right to Information Act, 2005Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Rti ByjuDocument5 pagesRti ByjuTulasee ReddiNo ratings yet

- Right To InformationDocument8 pagesRight To InformationAnjali PathakNo ratings yet

- Right To Information: Why in News?Document5 pagesRight To Information: Why in News?Deepeksh GaurNo ratings yet

- Rti NoteDocument7 pagesRti NoteHimanshu VermaNo ratings yet

- Right To InformationDocument5 pagesRight To InformationHello HiiNo ratings yet

- A Study On Right To Information ActDocument42 pagesA Study On Right To Information Actbanaman100% (1)

- Empowerment: The Right To InformationDocument7 pagesEmpowerment: The Right To InformationsaurabhNo ratings yet

- Free Flow of InformationDocument6 pagesFree Flow of InformationSatyendra SinghNo ratings yet

- History of The Right To Information ActDocument9 pagesHistory of The Right To Information ActWaqarKhanPathanNo ratings yet

- Right To Information - Notes For UPSC Indian PolityDocument11 pagesRight To Information - Notes For UPSC Indian PolityRAJARAJESHWARI M GNo ratings yet

- Good GovernanceDocument13 pagesGood GovernanceNEEL RAINo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Right To Information Act 2005Document8 pagesResearch Paper On Right To Information Act 2005Shivansh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- RTI in Bangladesh ContextDocument3 pagesRTI in Bangladesh ContextTasnia NazNo ratings yet

- Freedom of InfornationDocument5 pagesFreedom of InfornationRitika SinghNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Section - 8 (1) (D), (G), (I) of The RTI ActDocument19 pagesAn Analysis of The Section - 8 (1) (D), (G), (I) of The RTI Actbackupsanthosh21 dataNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - 5.1 RTIDocument6 pagesUnit 5 - 5.1 RTI21ubaa140 21ubaa140No ratings yet

- Research Paper On Right To Information Act, 2005Document8 pagesResearch Paper On Right To Information Act, 2005a_adhau100% (6)

- Right To Information 2005: Objective of RTIDocument10 pagesRight To Information 2005: Objective of RTIJONUS DSOUZANo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PAPER by HarshaDocument32 pagesRESEARCH PAPER by HarshaHarsha RaoNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Unit IIIDocument12 pagesHuman Rights Unit IIIPRAVEENKUMAR MNo ratings yet

- SafariDocument7 pagesSafariraghuvansh mishraNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknow: Civil Society and Public GrievancesDocument8 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknow: Civil Society and Public GrievancesJitesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknow: Civil Society and Public GrievancesDocument8 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknow: Civil Society and Public GrievancesJitesh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Right To Information Academike 20210223120533Document17 pagesRight To Information Academike 20210223120533SamirNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Right To Information Act 2005Document20 pagesNotes On The Right To Information Act 2005goyalheenaNo ratings yet

- Internship Research PaperDocument26 pagesInternship Research PaperGANESH KUNJAPPA POOJARINo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document57 pagesChapter 10Shubham RajrajNo ratings yet

- True Power of RTIDocument14 pagesTrue Power of RTIAnjali BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- 12.right To Information Act 2005Document4 pages12.right To Information Act 2005mercatuzNo ratings yet

- The Right To InformationDocument7 pagesThe Right To InformationMd. Akmal HossainNo ratings yet

- 11 - Chapter-7Document33 pages11 - Chapter-7illogical dramaNo ratings yet

- Session 3 - RTIDocument9 pagesSession 3 - RTI589 TYBMS Shivam JoshiNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Judgements On Right To Information - IpleadersDocument11 pagesSupreme Court Judgements On Right To Information - IpleadersDebapom PurkayasthaNo ratings yet

- Exemptions From Disclosure of Information Under Right To Information Act, 2005: A Methodical ReviewDocument19 pagesExemptions From Disclosure of Information Under Right To Information Act, 2005: A Methodical ReviewVinit StanislausNo ratings yet

- Right To Information ActDocument7 pagesRight To Information ActSourabh ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument8 pagesIndexaanyaNo ratings yet

- RTI SampleDocument8 pagesRTI SampleSwaroop DevalNo ratings yet

- Constitution LawDocument8 pagesConstitution LawJajju RaoNo ratings yet

- RTI EssayDocument7 pagesRTI EssayRohit GunasekaranNo ratings yet

- Right To Information Act, 2005: B.1 Objectives of The ActDocument9 pagesRight To Information Act, 2005: B.1 Objectives of The ActHarshada SinghNo ratings yet

- Be But A Few Secrets. The People of This Country by The: 1 TH TH TH THDocument21 pagesBe But A Few Secrets. The People of This Country by The: 1 TH TH TH THParul Anand100% (1)

- Administrative Law ProjectDocument21 pagesAdministrative Law ProjectAnonymous H1TW3YY51KNo ratings yet

- Wa0024.Document14 pagesWa0024.Pranjal BhattNo ratings yet

- DRTI CRTI 101 102 Right To InformationDocument92 pagesDRTI CRTI 101 102 Right To InformationAnu0000 SharmaNo ratings yet

- Article On RTIDocument11 pagesArticle On RTIKanhaiya SinghalNo ratings yet

- The Right of The People To Information On Matters and Documents of Public ConcernDocument3 pagesThe Right of The People To Information On Matters and Documents of Public ConcernAira RamosNo ratings yet

- Internship Research Paper - Vratika PhogatDocument19 pagesInternship Research Paper - Vratika Phogatinderpreet sumanNo ratings yet

- Civil Society ProjectDocument14 pagesCivil Society Projectayush singhNo ratings yet

- Anand Doctrinal On Right To Information ActDocument25 pagesAnand Doctrinal On Right To Information ActStanis Michael50% (2)

- CS and PGDocument55 pagesCS and PGsoumya jainNo ratings yet

- RTI Assignment 17 HGHJGHJFHJDocument9 pagesRTI Assignment 17 HGHJGHJFHJMd Haider AnsariNo ratings yet

- The Right To Information ActDocument10 pagesThe Right To Information ActsimranNo ratings yet

- Cyber Monday: View Deals NowDocument11 pagesCyber Monday: View Deals NowvenugopalNo ratings yet

- Bringing Information To The Citizens: CitationDocument6 pagesBringing Information To The Citizens: CitationAkash MauryaNo ratings yet

- Right To Information Fall of The Most Important LegislationDocument25 pagesRight To Information Fall of The Most Important LegislationKing SheikhNo ratings yet

- Right To Information Act (In Medical Practice)Document25 pagesRight To Information Act (In Medical Practice)P Vinod Kumar100% (1)

- Rti File DocumentDocument41 pagesRti File DocumentVanshika GheteNo ratings yet

- Study of Role of RTI ACT To Prevent Corruption and Capacity Building For Delivery of Government Services: Socio-Economic ImpactDocument4 pagesStudy of Role of RTI ACT To Prevent Corruption and Capacity Building For Delivery of Government Services: Socio-Economic ImpactEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- The Ehsan Jafri CaseDocument3 pagesThe Ehsan Jafri CaseRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- The Discreet Charm of The BJPDocument4 pagesThe Discreet Charm of The BJPRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Safe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityDocument6 pagesSafe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Trends in Agricultural ProductionDocument1 pageTrends in Agricultural ProductionRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiDocument2 pagesPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of India's "Democratic" ChoiceDocument3 pagesMaking Sense of India's "Democratic" ChoiceRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaDocument5 pagesRevisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- What Future For The Media in IndiaDocument3 pagesWhat Future For The Media in IndiaRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- ED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleDocument1 pageED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Decoding Dravidian PoliticsDocument4 pagesDecoding Dravidian PoliticsRajatBhatia100% (1)

- From 50 Years AgoDocument1 pageFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Lessons From A HangingDocument1 pageLessons From A HangingRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Homage To A Critic of MarxistPositivist HistoryDocument2 pagesHomage To A Critic of MarxistPositivist HistoryRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Indias Quarterly GDP Estimates at Factor Cost by Economic Activity Rs CroreDocument1 pageIndias Quarterly GDP Estimates at Factor Cost by Economic Activity Rs CroreRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Game Ugly AdministrationDocument2 pagesBeautiful Game Ugly AdministrationRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Deepening Democracy and Local GovernanceDocument5 pagesDeepening Democracy and Local GovernanceRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- From 50 Years AgoDocument1 pageFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Akshardham Judgment IDocument3 pagesAkshardham Judgment IRajatBhatiaNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction 2 Semester, AY 2018-2019 SyllabusDocument9 pagesJurisdiction 2 Semester, AY 2018-2019 SyllabusDiane JulianNo ratings yet

- Paradigms and Paradoxes of Victimology PDFDocument26 pagesParadigms and Paradoxes of Victimology PDFatjoerossNo ratings yet

- Unitedworld School of Law: TOPIC: Common Intention Under Criminal LawDocument7 pagesUnitedworld School of Law: TOPIC: Common Intention Under Criminal Lawmahek ravalNo ratings yet

- CCP Subject GuideDocument300 pagesCCP Subject GuideLessons In LawNo ratings yet

- MOGADISHU's CRIME PRONE HELIWAA DISTRICT LOOKS UP TO COMMUNITY POLICING TO SOLVE SECURITY CHALLENGESDocument4 pagesMOGADISHU's CRIME PRONE HELIWAA DISTRICT LOOKS UP TO COMMUNITY POLICING TO SOLVE SECURITY CHALLENGESAMISOM Public Information ServicesNo ratings yet

- Personal Branding WebinarDocument21 pagesPersonal Branding WebinarKM PERFORMANCESNo ratings yet

- J 2018 SCC OnLine All 2087 2018 Cri LJ 5010 2018 6 All Aniketchaudhary2j Gmailcom 20210907 104043 1 53Document53 pagesJ 2018 SCC OnLine All 2087 2018 Cri LJ 5010 2018 6 All Aniketchaudhary2j Gmailcom 20210907 104043 1 53AbhishekNo ratings yet

- Vikas Yadav V State of UPDocument256 pagesVikas Yadav V State of UPHARSHIL SHRIWASNo ratings yet

- Calamity and Disaster PreparednessDocument29 pagesCalamity and Disaster PreparednessGian Jane QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Forgetting Article 103 of The UN CharterDocument11 pagesForgetting Article 103 of The UN Chartershahab88No ratings yet

- In Re - Sabio 504 Scra 704 (2006)Document1 pageIn Re - Sabio 504 Scra 704 (2006)Shen TupasNo ratings yet

- Chavez Vs RomuloDocument13 pagesChavez Vs RomuloJayMichaelAquinoMarquezNo ratings yet

- Soriano Vs ListaDocument1 pageSoriano Vs ListaCarlota Nicolas Villaroman100% (1)

- Essay Regarding Current Affairs and Media LiteracyDocument2 pagesEssay Regarding Current Affairs and Media LiteracyFrancine SenapiloNo ratings yet

- Manuel Vs PeopleDocument2 pagesManuel Vs PeopleSeira AdolfNo ratings yet

- Trespass To Person - Assault, Battery and False Imprisonment in Torts LawDocument8 pagesTrespass To Person - Assault, Battery and False Imprisonment in Torts LawAkash KaranwalNo ratings yet

- Veet Facing Cultural Challenges in Pakistan: Srinidhi Naeital AnuragDocument16 pagesVeet Facing Cultural Challenges in Pakistan: Srinidhi Naeital AnuragKOTHAMASU STSS SRINIDHI VU21MGMT0500001No ratings yet

- CA 101 Lecture 13Document40 pagesCA 101 Lecture 13Johnpatrick DejesusNo ratings yet

- Taking The Human Rights Temperature at Bifs - The QuestionnaireDocument6 pagesTaking The Human Rights Temperature at Bifs - The Questionnaireapi-249839362No ratings yet

- 1.2d - Not-For-ProfitDocument17 pages1.2d - Not-For-ProfitJoe TicarNo ratings yet

- Engagement Contract: - Client's Name: - AddressDocument2 pagesEngagement Contract: - Client's Name: - AddressJohn Aarone AdventoNo ratings yet

- An Open Letter To Mr. Salahuddin Shoaib Choudhury Editor of The Ban Glades Hi Tabloid The Weekly Blitz To Stop Distribution of False and Defamatory News Regarding William Nicholas Gomes-2Document1 pageAn Open Letter To Mr. Salahuddin Shoaib Choudhury Editor of The Ban Glades Hi Tabloid The Weekly Blitz To Stop Distribution of False and Defamatory News Regarding William Nicholas Gomes-2Nicholas GomesNo ratings yet

- Abelita V DoriaDocument2 pagesAbelita V DoriaMay Angelica TenezaNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument19 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Terry Wiley Home Shootout Court Documents (Redacted)Document10 pagesTerry Wiley Home Shootout Court Documents (Redacted)Truth and JusticeNo ratings yet

- Road To StatehoodDocument48 pagesRoad To Statehoodstatehood hawaiiNo ratings yet

- Business CommunicationDocument16 pagesBusiness CommunicationHriday PrasadNo ratings yet

- Conservatism A State of FieldDocument21 pagesConservatism A State of Fieldcliodna18No ratings yet

- Automatism Lecture NotesDocument2 pagesAutomatism Lecture NotesninnikNo ratings yet

- Written Submission of Victim For ConvictionDocument11 pagesWritten Submission of Victim For ConvictionSunil KNo ratings yet