Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2.3 Anholt Editorial - The Danish Cartoons Controversy

2.3 Anholt Editorial - The Danish Cartoons Controversy

Uploaded by

Claudia Horobet0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views4 pagesarticle about danish cartoons

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentarticle about danish cartoons

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views4 pages2.3 Anholt Editorial - The Danish Cartoons Controversy

2.3 Anholt Editorial - The Danish Cartoons Controversy

Uploaded by

Claudia Horobetarticle about danish cartoons

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

change, but they can report it, help to

consolidate it and to some extent speed

it on its way.

As I have often observed, Japan

provides the last centurys best example

of enhanced competitive identity. The

effect of Japans economic miracle on the

image of the country itself was quite as

dramatic as its effect on the countrys

output: 40 or even 30 years ago, made

in Japan was a decidedly negative

concept, as most Western consumers had

based their perception of Japan on their

experience of shoddy, second-rate

products ooding the marketplace. The

products were cheap, certainly, but they

were basically worthless. In many

respects the perception of Japan was

much as Chinas has been in more recent

years.

Yet Japan has now become enviably

synonymous with advanced technology,

manufacturing quality, competitive

pricing and even style and status. Japan,

indeed, passes the best branding test of

all: whether consumers are prepared to

pay more money for functionally

identical products, simply because of

where they come from. It is fair to say

that in the 1950s and 1960s most

Europeans and Americans would only

buy Japanese products because they were

signicantly cheaper than a Western

alternative; now, in certain very valuable

market segments, such as consumer

electronics, musical instruments and

motor vehicles, Western consumers will

consistently pay more for products

manufactured by previously unknown

brands, purely on the basis that they are

perceived to be Japanese.

I am often asked why and when the

images of countries, cities and regions

change. In my experience they only ever

change for two reasons: either because

the country changes, or because it does

something to people.

The rst kind of change is usually a

very gradual process, and the majority of

success stories about brand change are

not stories of brand management at all:

Irelands change from a collapsing rural

backwater in the 1960s to the Celtic

Tiger of the 1990s was primarily a

miracle of foreign direct investment

promotion; South Africas change from a

virtual pariah to the Rainbow Nation

of today was rst and foremost a political

miracle, triggered by the end of

apartheid, the election of Nelson

Mandela and the formation of one of the

most innovative constitutions created in

the last century. In both cases, the

nation brand, or what I prefer to call

the competitive identity of the country, was

built through its actions and behaviours,

and not through any deliberate attempt

to market the country directly.

The prominent marketing campaigns

carried out by South Africa may have

helped a little to shorten the lag between

reality and global perception, by

supporting what was in the news media

to bring the changes to peoples

attention, and help summarise and

characterise them. In such cases

marketing communication can certainly

play a role: but it does seem to conrm

that all it can really do is capture the

zeitgeist and reect changes in society

that are already taking place.

Communications cannot substitute

Palgrave Macmillan Ltd 1744070X/06 $30.00 Vol. 2, 3, 179182 Place Branding 179

Editorial

Muhammad in Denmarks Jyllands-Posten

and other newspapers, which eventually

resulted in rioting and numerous deaths,

as well as widespread boycotting of

Danish and other Scandinavian goods in

shops all over the Muslim world. A

serious rift appeared to have opened up

between the values of Islam and some

aspects of secular liberal Western

democracy.

In the 2005 Q4 study, Norway and

Denmark remained in level positions

almost throughout the index, suggesting

that many people, especially beyond

Northern Europe, do not have a strong

sense of the differences between these

two countries, even when it comes to

distinguishing between their exports (this

despite the fact that Danish brands like

Lego, Bang and Olufsen, Carlsberg and

several others are associated with

Denmark, while Norway produces no

famous global brands). The strongest

component of both countries images was

in governance, where both ranked within

the top ve on every governance

question (with Norway consistently a

shade ahead of Denmark). This tted in

with a fairly well-established traditional

perception rooted, like most

perceptions, in reality that Northern

European and especially Scandinavian

countries are fairly, efciently and

liberally governed, with a strong tradition

of social welfare and a good record in

international relations and development.

Elsewhere in the world Denmarks

scores remained more stable, although

there was a slight depression in the

scoring from the panellists in Central

Europe (Hungary, Poland, Estonia and

the Czech Republic), for example on

key questions about peoples interest in

Danish products and services, their

expectation of being made to feel

welcome if they visit the country, their

propensity to employ a Dane and their

view of the Danish governments

Again, though, the change in the

image of Japan over the second half of

the 20th century was not primarily

designed as an image change: it was an

export, design, technological and

industrial miracle. South Korea, and

more recently China, have quite

deliberately followed Japans lead in this,

but with the advantage of hindsight are

dealing with the image simultaneously

with the product change, and using

brand management techniques to build

their corporate and national reputations

as they build their product which is

why they are getting there faster.

The second reason why the images of

countries change is not when things

happen to the country, but when people

are personally affected by the place in

some way. In such cases national

reputation can change quite suddenly in

the minds of certain individuals or

groups.

This can be a positive change: in the

Nation Brands Index data, I have found

a statistically signicant correlation

between a positive experience of visiting

a country and positive feelings about its

products, its government, its culture, its

people. More research is needed in this

area, but an interesting hypothesis to

work with at this point would be that

any positive experience of a country, its people

or its productions tends to create a positive

bias towards some or all aspects of the

country.

Or, of course, it can be negative. A

direct attack on the individuals self,

country, values, religion or population,

whether real or perceived, can damage

the brand in that individuals mind in an

equally powerful way: the most striking

example of this since the Nation Brands

Index started was the impact of the

Danish cartoon crisis.

Last December an international furore

broke over the publication of satirical

cartoons depicting the Prophet

180 Place Branding Vol. 2, 3, 179182 Palgrave Macmillan Ltd 1744070X/06 $30.00

Editorial

the same time, and they can respond to

surveys like the NBI in different ways

too: as consumers, as politically aware

national or global citizens or as

individuals thinking about their own

lives, tastes and careers.

Given the nature of the survey, it is

quite likely that in previous editions of

the NBI these relatively pro-Western

respondents were expressing their views

about Denmark and other mature

Western economies as consumers or

potential consumers of their products,

tourism, popular culture, employment

and education opportunities and so forth.

But if Denmark touches a different nerve

a political, personal, cultural or

religious one then the reaction may

temporarily or even permanently drown

out what they feel for the country in

other ways. We have all seen images of

CocaCola-drinking, Nike-wearing

youths in the Middle East and South

Asia burning American ags.

This particular episode, like all

wildres, started in one small place, but

spread rapidly because it found dry tinder

and favourable winds (perhaps

predictably, some people suspect arson).

In consequence it soon created a violent

impact well beyond Denmarks borders.

As the Arab News reported on 28th

January, 2006:

Many international brands have become

targets of the recent boycott of Danish

products, thanks to the confusion of consumers

caused in part by the misinformation

distributed by the proponents of the ban. The

email I received said that NIDO is one of the

Danish products, so I stopped buying it, said

Saudi teacher Khaled Al-Harthi, who didnt

know that NIDO is a product of the Swiss

Nestle Company. A ier obtained by Arab

News calls for boycotting Danish and

Norwegian products . . . the ier listed many

items that are not products of Denmark,

including Kinder (owned by Italys

Ferrero-Rocher) and New Zealands Anchor.

contribution to human rights and

international peace and security. At the

further end of the spectrum, the

American panels average scores for

Denmark went up slightly perhaps

reecting a sense of relief that, for once,

somebody else was in trouble.

By contrast, the Egyptian panels

average scores for China rose a

suggestion that the whole axis of its

global loyalties has undergone a slight

shift.

Denmark was the only country in the

NBI that suffered a reduction in its mean

overall score between 2005 Q4 and 2006

Q1.

Although some of the changes reported

here are subtle, often no more than a few

percentage points, they are signicant

because country scores generally move

very little from one quarter to the next.

Peoples views of other countries are

generally quite xed and stable, and it

takes something very serious indeed to

make them revise their views. Above all,

it takes something personal.

And it goes without saying that this

effect can be prolonged and reinforced

more or less at will from generation to

generation through education and

indoctrination if it is in the interests of

society or governments to do so

which is one reason why it is impossible

to make any predictions about how long

this effect will last in the case of

Denmark.

Generally, if an action is strongly out

of character with the nations reputation,

peoples beliefs about that nation will

return to their previous state relatively

quickly; but it seems clear that the

respect expressed by the Egyptian,

Turkish, Indonesian and Malaysian

respondents for Denmark prior to the

cartoons episode was something that

existed in one part of their being but not

in another. People can hold several

contradictory feelings about countries at

Palgrave Macmillan Ltd 1744070X/06 $30.00 Vol. 2, 3, 179182 Place Branding 181

Editorial

exporters are caught in the cross-re and

their products boycotted. Even other

countries have suffered because they

happen to lie in the same geographical

region and have some brand values in

common.

If we pursue the metaphor of national

reputation as brand image, the nature of

the dilemma becomes clear. Were such

an episode to threaten the well-being

and reputation of a corporation, it would

be obvious what to do: the chief

executive would address all staff, warn

them that they are all equally responsible

for preserving the organisations good

name and demand that they behave on

brand or lose their jobs.

But corporations are not democracies,

they are a species of tolerated tyranny. As

the prime minister of Denmark pointed

out, he is not and cannot be responsible

for the behaviour of the free media in a

democracy, as long as they act within the

law. Perhaps on this occasion the law was

inadequate, and perhaps in an

increasingly interconnected world and

increasingly multiracial societies the old

models of national law need to evolve

faster than they currently do. Perhaps in

an enlightened modern society the forces

of education, cultural sensitivity and

respect could and should operate more

effectively to prevent such episodes than

the blunt instrument of the law.

But the fact remains that although

countries depend on their reputations as

much as corporations do, they have

quite rightly very little power to

control the way those reputations are

treated or mistreated by their own

citizens. Nations being viewed as single

brands is a phenomenon of growing

importance which is increasingly resistant

to direct control and who knows

where that will lead us?

Simon Anholt

Managing Editor

. . . Zakaria Ismail, manager of Al-Malki

supermarket, said they would start hanging signs

indicating Danish products. They had to do so

in order to reduce their loss of sales of products

that are mistaken as Danish . . . He said that all

customers now generated the habit of reading

the source of each product to make sure of its

origin. Even old people who cannot read, are

asking, Where is this made? he said.

The episode is a stark illustration of the

real meaning of globalisation: almost

every nation and culture on earth is now

sharing elbow room in a single

information space. No conversation is

private any longer, no media are

domestic and the audience is always

global. And everybody knows what

happens when a group of human beings

with different backgrounds, habits, values

and ambitions are thrown together in the

same crowded space: sooner or later,

tempers start to fray. Somebody treads on

someone elses toes; some say by accident

and some say on purpose; insults get

traded, a ght breaks out.

The implications of the Danish

cartoons episode are profound and leave

us with several unanswerable questions. It

is a universal human trait, whether we

like it or not, to brand other countries,

other races, other religions, other cultures.

No matter how complex or even

contradictory they are, we often resort to

treating them as single entities. How

quickly our disapproval of one

governments foreign policy can lead to

mistrust or persecution of that countrys

people; the failure of one company can be

taken as indicative of the imminent failure

of its countrys economy; admiration for a

single media star can lead to an imaginary

liking for the entire population of the

country. This case is no different: the

actions of one independent newspaper are

blamed on the people of the country, the

government is expected to explain or

resolve the issue and the countrys

182 Place Branding Vol. 2, 3, 179182 Palgrave Macmillan Ltd 1744070X/06 $30.00

Editorial

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi AdichieDocument19 pagesAmericanah by Chimamanda Ngozi AdichieRandom House of Canada35% (31)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- AC7114 Rev M NADCAP AUDIT CRITERIADocument37 pagesAC7114 Rev M NADCAP AUDIT CRITERIARaja Hone100% (2)

- SEO Services Contract Template Free Microsoft WordDocument12 pagesSEO Services Contract Template Free Microsoft WordDanz HolandezNo ratings yet

- INFERTILITY Obg SeminarDocument19 pagesINFERTILITY Obg SeminarDelphy VargheseNo ratings yet

- General Aspects of Reinforced PlasticsDocument2 pagesGeneral Aspects of Reinforced PlasticsClaudia HorobetNo ratings yet

- Lucrări Consultate Cărţi: - Content, Impact and Regulation, Editura Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ManhwahDocument6 pagesLucrări Consultate Cărţi: - Content, Impact and Regulation, Editura Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ManhwahClaudia HorobetNo ratings yet

- Alexandru Horobet The Great Fire of LondonDocument12 pagesAlexandru Horobet The Great Fire of LondonClaudia HorobetNo ratings yet

- C81e7global Brand Strategy - Unlocking Brand Potential Across Countries, CulturesDocument226 pagesC81e7global Brand Strategy - Unlocking Brand Potential Across Countries, CulturesClaudia HorobetNo ratings yet

- CoverDocument1 pageCoverClaudia HorobetNo ratings yet

- Types of Franchise MarketingDocument3 pagesTypes of Franchise MarketingTerminal VelocityNo ratings yet

- Letter To SponsorDocument11 pagesLetter To SponsorJeremiah Miko LepasanaNo ratings yet

- Vertigo TestDocument6 pagesVertigo Testalam saroorNo ratings yet

- Ethics Question BankDocument3 pagesEthics Question BankNishant IrudayadasonNo ratings yet

- Variation Order (AS-STAKED) U.P. Biodiversity Building Phase IIDocument10 pagesVariation Order (AS-STAKED) U.P. Biodiversity Building Phase IIHonesto LorenaNo ratings yet

- Publix ApplicationDocument3 pagesPublix Applicationapi-297971686No ratings yet

- Iphone XR 256 GB Invoice PDF FreeDocument1 pageIphone XR 256 GB Invoice PDF FreeLloydeeIce100% (1)

- BM CACV 2019-571 Hong Kong Mansion Common AreaDocument23 pagesBM CACV 2019-571 Hong Kong Mansion Common AreaEconomist KwokNo ratings yet

- Dementia Core Skills Education and Training FrameworkDocument95 pagesDementia Core Skills Education and Training FrameworkMirela Georgiana SchiopuNo ratings yet

- F 4 18 2021 R Corrigendum 22 03 2023 PSDocument1 pageF 4 18 2021 R Corrigendum 22 03 2023 PSadnan khanNo ratings yet

- The Case of ErikaDocument2 pagesThe Case of Erikarenz taniguchi100% (3)

- Chapter 09 Indirect and Mutual HoldingsDocument12 pagesChapter 09 Indirect and Mutual HoldingsNicolas ErnestoNo ratings yet

- Gazette Notification B.tech 2nd June 2018 28112018Document9 pagesGazette Notification B.tech 2nd June 2018 28112018Bhagwan Das SharmaNo ratings yet

- DMMMSU Open University Accomplishment 2019Document5 pagesDMMMSU Open University Accomplishment 2019Joanne Camus RiveraNo ratings yet

- Mid Term EvaluationDocument6 pagesMid Term Evaluationapi-338285420No ratings yet

- Twilight Struggle Solitaire VariantDocument2 pagesTwilight Struggle Solitaire VariantKarlo Marco Cleto100% (1)

- Network Topology Comparison: Topology Information Transfer Setup Expansion Troubleshooting Cost Cabling ConcernsDocument8 pagesNetwork Topology Comparison: Topology Information Transfer Setup Expansion Troubleshooting Cost Cabling ConcernsAshfaq RahmanNo ratings yet

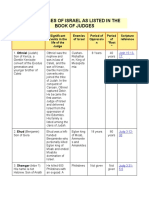

- The Judges of Israel As Listed in The Book of JudgesDocument6 pagesThe Judges of Israel As Listed in The Book of JudgesZaira RosentoNo ratings yet

- Test Law of AgencyDocument28 pagesTest Law of AgencyA24 IzzahNo ratings yet

- MDA Legislative Report Elk 2022Document3 pagesMDA Legislative Report Elk 2022inforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Kerala Case Jto Pay ScaleDocument33 pagesKerala Case Jto Pay ScaleVijaya Raghava Rao TakkellapatiNo ratings yet

- MQP Ans 04Document3 pagesMQP Ans 04vision xeroxNo ratings yet

- Literary Analysis HandoutDocument3 pagesLiterary Analysis Handoutapi-266273096100% (1)

- Room Sales ManagementDocument32 pagesRoom Sales Managementlioul sileshi100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Microeconomics For Managers Winter 2013Document34 pagesChapter 1 Microeconomics For Managers Winter 2013Jessica Danforth GalvezNo ratings yet

- Sample Thesis Survey QuestionnaireDocument4 pagesSample Thesis Survey Questionnaireh0dugiz0zif3100% (1)