Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Img 007

Uploaded by

Portgus D PolanyaanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Img 007

Uploaded by

Portgus D PolanyaanCopyright:

Available Formats

The Controversy on Freedom in Science in the Nineteenth Century

ITlt1 ・ー

)ination, there should be no thoughit contained an important element of truth.12 Now, after the lapse

of years, Virchow claims that such theories should not be taught to

!e, reminiscent of Polanyi'S students.

_tted that faith has its place With some justice, Haeckel lays emphasis on Virchow's ignorance of

deT Wissenschaft ein gewisses morphology, especially so far as the lower animals are concerned, and does

lg10n there were three parts- not hesitate to agree with the latter's confession of the limitations of his

同山相川川川川川川

dmiddle path of faith, and a own knowledge.

= himselfCould not entirely Haeckel ridicules the idea that nothing is known except what can be

he saw how necessary it was proved by experiment. Virchow allows that fossils actually represent the

remains of extinct animals, though no absolute proof of this can be

n of inquiry (die Freiheii der brought forward, and no experiment devised to settle the matter. The

Irkers must pose and discuss Mesozoic mammalia are known only by血eir lower Jaws. It is reasonable

to the public as doctrines. He to assume that the rest of the skeleton was mammalian. Virchow, however,

a that man had animal ances一 to be consistent, must suppose that in these remarkable creatures the only

ヒes might be fわund in the fu- skeletal element was the lower Jaw !

nore ape-like than the most Haeckel uses his M1 capacity as a polemical writer to attack Virchow'S

suggestion that the doctrine of evolution has some connection with social-

that scientists would receive ism. Virchow's vague remarks on this subject are interpreted by Haeckel

ld support in whatever direcI as meaning that the horrors of the Paris Commune of 1871 were somehow

s speech made a profound to be regarded as a consequence of the spread of Darwin's ideas. Haeckel

lrOughOut Germany. points out with some effect that the reverse is true ; that Darwinism could

:leaf distinction between die be used, on the contrary, to support aristocratic regimes. Socialists, he says,

t加enschaftlichen Lehre. The should try to stifle the doctrine, for its teaches that inequality is essential to

・

汲red the teaching of specula-

progress. He makes it clear that he is no socialist himself,and remarks

lat the reputation of science savagely on 'den bodenlosen Widersinn der socialistischen Gleichmacherei '.

He expresses his surprise that Virchow should requre scientists to limit

their teaching to demonstrable facts, while clerics are pemitted to instruct

)w amived, but the latter's their pupils on miracles and religious dogmas.

nonth. Haeckel was not the Here and there Haeckel descends to downright abuse. For instance, he

P

・eply took the form of a small

describes Bastian (a supporter of Virchow) as the 'Acting Head Privy-

unich conference,10 and sub- Councillor of Confusion'. He blames Virchow for being too much bound

ledwith a preface by T. H. up ln POlitical life, for argung like a Jesuit, for wasting his time in measur-

my Of Haeckel's wdtings. It ing human skulls, and for moving from a small university (WBrzburg) to a

. The argument is eirective, large one Perlin). He views with horror the possibility that German

sciencemight be centrally planned under the domination of the capital

詑n tO discredit Virchow by a city, and castigates the biologists of Berlin University for theirmiSunder-

e owes to his former teacher, standing and disregard of the theory of evolution.

st converted him to monism, Huxley'S preface to the English edition of Haeckel's book is a sparkhng

life. He claims, however, that little essay in characteristic vein.13 0nemight perhaps have expected him

einoutlook. The latter was to come down heavily on Haeckel's side, for the two men were personal

le Was Willing to discuss his friends and both were public champions Of the evolutionary doctrine. He

: himself to the recitation of glVeS full credit, however, to Virchow, by whose arguments he is clearly

lnS reject the publication of impressed. indeed, he丘nds himself able to agree with. every Important

tneralization, Omnis cellula e general proposition in Virchow's address,and is surprised that it should

it was not universally valid, have been so unfavourably received by some.

93

You might also like

- Ayer-Revolution in PhilosophyDocument128 pagesAyer-Revolution in PhilosophyTrad AnonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CosmologyDocument29 pagesIntroduction To CosmologyArun Kumar UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Stephen J. Gould & Immanuel Velikovsky - Essays In the Continuing Velikovsky AffairFrom EverandStephen J. Gould & Immanuel Velikovsky - Essays In the Continuing Velikovsky AffairNo ratings yet

- The Distribution of The GalaxiesDocument521 pagesThe Distribution of The GalaxiesHorváth Béla100% (6)

- 207 PleomorphismDocument6 pages207 PleomorphismboninhNo ratings yet

- Ludwig Klages - Biocentric MetaphysicsDocument55 pagesLudwig Klages - Biocentric Metaphysicsddft100% (1)

- Bruno LatourDocument13 pagesBruno LatourrodrigoielpoNo ratings yet

- Brennan - Whitehead On Plato S CosmologyDocument13 pagesBrennan - Whitehead On Plato S CosmologyFélixFernándezPalacioNo ratings yet

- E. P. Thompson "The Poverty of Theory or An Orrery of Errors"Document157 pagesE. P. Thompson "The Poverty of Theory or An Orrery of Errors"João Pedro BuenoNo ratings yet

- Adam Parry Studies in Fifth Century Thought and Literature Yale Classical Studies No. 22 2009Document283 pagesAdam Parry Studies in Fifth Century Thought and Literature Yale Classical Studies No. 22 2009Lilla Lovász100% (1)

- The Paradoxical Structure of Existence PDFDocument173 pagesThe Paradoxical Structure of Existence PDFMuhammad HareesNo ratings yet

- Topic Sky - Ielts Ngoc BachDocument3 pagesTopic Sky - Ielts Ngoc BachVu DungNo ratings yet

- 1 Social TheoriesDocument13 pages1 Social TheoriesaxhaferajNo ratings yet

- Existentialism MounierDocument149 pagesExistentialism MouniermaxxNo ratings yet

- Evolution Wolfgang SmithDocument7 pagesEvolution Wolfgang Smithealzueta4712100% (1)

- 10 - Cyclic SedimentationDocument291 pages10 - Cyclic SedimentationSaditte Manrique ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Quine (1981) Has Philosophy Lost Contact PeopleDocument3 pagesQuine (1981) Has Philosophy Lost Contact Peoplewackytacky135No ratings yet

- Phil at The End of The Century - Hans JonasDocument21 pagesPhil at The End of The Century - Hans Jonasfilosofiaufpi100% (1)

- Manfred Frank - Schelling - S Critique of Hegel and The Beginnings of Marxian Dialectics PDFDocument18 pagesManfred Frank - Schelling - S Critique of Hegel and The Beginnings of Marxian Dialectics PDFSegismundo SchcolnikNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Prepare Construction MaterialsDocument41 pagesModule 1 - Prepare Construction Materialsefren gNo ratings yet

- Life and Matter: A Criticism of Professor Haeckel's "Riddle of the Universe"From EverandLife and Matter: A Criticism of Professor Haeckel's "Riddle of the Universe"Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- (Leszek Kolakowski) Husserl and The Search For CerDocument86 pages(Leszek Kolakowski) Husserl and The Search For CerCastelmoreNo ratings yet

- Habermas, Heidegger and Berg Science As Instrumental ReasonDocument27 pagesHabermas, Heidegger and Berg Science As Instrumental ReasonJavier AguirreNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument217 pagesUntitledDiogo M.No ratings yet

- Latour Descola ViveirosDocument4 pagesLatour Descola ViveirosTom ZeNo ratings yet

- Seismic Design Methodology For Buried StructuresDocument6 pagesSeismic Design Methodology For Buried StructuresClaudioDuarteNo ratings yet

- Img 006Document1 pageImg 006Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 008Document1 pageImg 008Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 005Document1 pageImg 005Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 009Document1 pageImg 009Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 004Document1 pageImg 004Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Manfred Frank Schelling S Critique of Hegel and The Beginnings of Marxian Dialectics PDFDocument18 pagesManfred Frank Schelling S Critique of Hegel and The Beginnings of Marxian Dialectics PDFkyla_bruffNo ratings yet

- Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)From EverandEvidence as to Man's Place in Nature (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)No ratings yet

- 2004 Allchin Pseudohistory and PseudoscienceDocument18 pages2004 Allchin Pseudohistory and PseudoscienceRonivan Sousa da SilvaNo ratings yet

- A. J. Lustig - Erich Wasmann, Ernst Haeckel, and The Limits of ScienceDocument8 pagesA. J. Lustig - Erich Wasmann, Ernst Haeckel, and The Limits of ScienceKein BécilNo ratings yet

- Uniqueness o Find I 00 Me DaDocument200 pagesUniqueness o Find I 00 Me DaDaniela Nicoleta SbarnaNo ratings yet

- Philosophical and Historical Aspects of The Origin of LifeDocument11 pagesPhilosophical and Historical Aspects of The Origin of LifeAlejandroNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 143.107.150.86 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 23:46:38 UTCDocument10 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 143.107.150.86 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 23:46:38 UTCBruno S. MenegattiNo ratings yet

- BIO Huxley His Life Work by LeightonDocument104 pagesBIO Huxley His Life Work by LeightonAnonymous 6oTdi4No ratings yet

- Darwinism EssayDocument19 pagesDarwinism EssayanpofNo ratings yet

- Ritchie DarwinHegel 1890Document21 pagesRitchie DarwinHegel 1890MarianNo ratings yet

- Maup preexistenceXVIIIDocument26 pagesMaup preexistenceXVIIIlicornutNo ratings yet

- Anti-Darwin, Anti-Spencer: Friedrich Nietzsche'S Critique of Darwin and "Darwinism"Document22 pagesAnti-Darwin, Anti-Spencer: Friedrich Nietzsche'S Critique of Darwin and "Darwinism"janesprightNo ratings yet

- William Whewell (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)Document14 pagesWilliam Whewell (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)juanNo ratings yet

- Philosophy From An Antiphilosopher: Paul Valery: Jacques BouveresseDocument28 pagesPhilosophy From An Antiphilosopher: Paul Valery: Jacques BouveresseduyuuuuuNo ratings yet

- William WhewellDocument25 pagesWilliam Whewellsalarbid100% (1)

- Cassuto S The Documentary Hypothesis and PDFDocument18 pagesCassuto S The Documentary Hypothesis and PDFIves RosenfeldNo ratings yet

- Calvin G - Normore: The Modern Schoolman, LXXII, January/March 1995 273Document9 pagesCalvin G - Normore: The Modern Schoolman, LXXII, January/March 1995 273Carlo FuentesNo ratings yet

- Review of Baldasar Heseler, Vesalius First Public Anatomy in BolognaDocument3 pagesReview of Baldasar Heseler, Vesalius First Public Anatomy in BolognaKirsten SimpsonNo ratings yet

- In Defense of Presentism - by David L. Hull. History and Theory, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb., 1979), Pp. 1-15Document16 pagesIn Defense of Presentism - by David L. Hull. History and Theory, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Feb., 1979), Pp. 1-15AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Brmedchirj272232 0003Document10 pagesBrmedchirj272232 0003aceNo ratings yet

- 1000 Doctors (And Many More) Against VivisectionDocument155 pages1000 Doctors (And Many More) Against VivisectionBryan GraczykNo ratings yet

- The Principle of PhenomenologyDocument23 pagesThe Principle of Phenomenologymartinadam82No ratings yet

- Autobiography and Selected Essays (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandAutobiography and Selected Essays (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- Punnett1928Ovists and AnimalculistsDocument28 pagesPunnett1928Ovists and AnimalculistsdeegaziNo ratings yet

- DEBUS, A. G. Chemists, Physicians, and Changing Perspectives On The Scientific RevolutionDocument16 pagesDEBUS, A. G. Chemists, Physicians, and Changing Perspectives On The Scientific RevolutionRoger CodatirumNo ratings yet

- Feyerabend: Science: Paul and The AnarchistDocument4 pagesFeyerabend: Science: Paul and The AnarchistShinta PriyanggaNo ratings yet

- Somerset FinalDocument17 pagesSomerset FinalarNo ratings yet

- E P THOMPSON The Poverty of Theory or An Orrery of Errors PDFDocument314 pagesE P THOMPSON The Poverty of Theory or An Orrery of Errors PDFDamián TrucconeNo ratings yet

- Shapin LRBPolanyi PDFDocument10 pagesShapin LRBPolanyi PDFPortgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 010Document1 pageImg 010Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 002Document1 pageImg 002Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Img 001Document1 pageImg 001Portgus D PolanyaanNo ratings yet

- Earths Rotation and RevolutionDocument9 pagesEarths Rotation and RevolutionMarbeth Cunanan FariñasNo ratings yet

- Topographic Map of Vat CampDocument1 pageTopographic Map of Vat CampHistoricalMapsNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Introduction, Definition and Concept of Psychology: StructureDocument49 pagesUnit 1 Introduction, Definition and Concept of Psychology: StructureSimeen aliNo ratings yet

- Optimisation of Bench-BermDocument25 pagesOptimisation of Bench-BermMacarena Ulloa MonsalveNo ratings yet

- Workshop Was and WereDocument2 pagesWorkshop Was and WereTatiana Isabel Castillo AnayaNo ratings yet

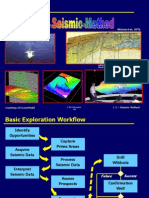

- Seismic MethodDocument21 pagesSeismic MethodShah JeeNo ratings yet

- LN49Document198 pagesLN49Đạt NguyễnNo ratings yet

- TMT General BrochureDocument34 pagesTMT General BrochureKasezga TemboNo ratings yet

- CV GanjarDocument2 pagesCV GanjarRusman GhaniNo ratings yet

- Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani Instruction Division SECOND SEMESTER 2016-2017 Midsem Exam Seating ArrangementDocument25 pagesBirla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani Instruction Division SECOND SEMESTER 2016-2017 Midsem Exam Seating ArrangementANKUR SONINo ratings yet

- Photosynthesis and Respiration and Plant ResponsesDocument2 pagesPhotosynthesis and Respiration and Plant Responsesapi-169639475No ratings yet

- Teks Deskripsi Dan Teks Recount: Nama: Ramah Della Putri Kelas: X.IPS.BDocument10 pagesTeks Deskripsi Dan Teks Recount: Nama: Ramah Della Putri Kelas: X.IPS.BbobygannyNo ratings yet

- Science Wonder LessonDocument3 pagesScience Wonder Lessonapi-235337221No ratings yet

- Power Point Volcanic EruptionDocument18 pagesPower Point Volcanic Eruptionwandi primaNo ratings yet

- NGWA2003Document6 pagesNGWA2003jaggasingh11No ratings yet

- April 2013Document185 pagesApril 2013Jorge Orejarena GarciaNo ratings yet

- Posterior Palatal SealDocument2 pagesPosterior Palatal SealizcooiNo ratings yet

- Numerical Study of Pile-Up in Bulk Metallic GlassDocument9 pagesNumerical Study of Pile-Up in Bulk Metallic GlassAditya DeoleNo ratings yet

- Gujarat Technological University Environmental EngineeringDocument3 pagesGujarat Technological University Environmental EngineeringHarshil KachhadiyaNo ratings yet

- Main Campus Map RevisedDocument2 pagesMain Campus Map Revisedm.rautenbach00No ratings yet

- Board of Intermediate & Secondary Education Saidu Sharif SwatDocument2 pagesBoard of Intermediate & Secondary Education Saidu Sharif SwatMUSHTAQ AHMADNo ratings yet

- Ice Ages (Milankovitch Theory) 995Document9 pagesIce Ages (Milankovitch Theory) 995enasapolousNo ratings yet