Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Problems of Spoken Written Arabic

Uploaded by

jimineuropaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Problems of Spoken Written Arabic

Uploaded by

jimineuropaCopyright:

Available Formats

Arabic for non-natives series-Hussein Maxos: Comparative Studies 1995-2002 IRAMES Group Damascus

a k= I _ms I ei

Problems of Spoken-Written Arabic

Introduction

Why some Arabs dont like to speak Arabic

Common Misconceptions

Recommended Solutions

Dialectical Map

Spoken and Written on TV and radio broadcasts

By Hussein Maxos www.hmaxos.com Telefax: 963 11 332 5056

Introduction: Language and identity

Spoken Arabic, including the differences within the Arabic dialects and accents, has

been subject to groundless exaggerations and serious misunderstanding due to several

factors. First, the lack of serious studies conducted by native speakers who tend to judge

Spoken Arabic from a localist, pan-Arab nationalist or Islamist (but never scientific)

point of view. Second, the efforts made by the orientalists were viewed as a foreign and

lacked a firm grounding. Localism flourished after World War I when Britain and

France divided the Arab world into small separate states and each state proceeded to

establish its own government, media and educational system. Sensing the danger of

deeper separatism, the Arab nationalist and Islamist governments, which are in the

majority, decided to adopt written Arabic for all forms of written communication and

education. As result, they underestimated and ignored their spoken Arabic. The other

extreme is typified by the localist/sectarianist governments in Egypt and Lebanon who

gave excessive attention to their spoken Arabic, as to the extent that many of them no

longer consider their dialects Arabic nor themselves as Arabs. Both these attitudes are

unscientific and have led to serious problems. Noam Chomsky, The American linguist

and political analyst, in his book Language and Responsibility says: In the old Ottoman

Empire, regions such as the Levant incorporated numerous local communities, related to each

other in various ways, and with a good deal of linguistic variation as well. Nobody spoke the

Classical Arabic taught in schools, but the so-called dialects were considered inferior. The

intervention of the Western imperial powers led to a system of states, leaving bitter and

unresolved conflicts and antagonisms, a system in which each individual must define himself as

belonging to a nation or a nation-state. It is a system imposed from the outside on a region ill-

adapted to it.

Today, Arabs learn their spoken language in a passive and spontaneous way from their

everyday experiences in daily life while they study exclusively written Arabic. In fact,

Arab students are scrupulously required to avoid use of dialect in schools and are taught

to stigmatize spoken Ammia whenever possible in order to maintain their national or

religious identity. Localist and sectarianist systems amplify the distinction of their

dialects-accents also for the sake of identity emphasis at the expense of the shared

language and culture with the rest of the Arab world. These problems of identity crisis,

Arabic for non-natives series-Hussein Maxos: Comparative Studies 1995-2002 IRAMES Group Damascus

identity conflicts and ideological games have served to weaken the language and have

created many misconceptions and difficulties for the average Arab.

The problem is even worse for non-native students of Arabic, because they do not have

the advantage of being exposed to years of spontaneous learning. When non-natives

come to the Arab world to study Arabic, they are usually encouraged to study only

written Arabic and speak only written Arabic. Paradoxically, Arabs themselves by and

large cannot speak written Arabic correctly. When Arabs attempt to speak written

Arabic with non-natives or, say in an interview on TV, they quickly get confused and

start to mix written forms with spoken language in an odd way. How can they expect a

foreigner to be better in this respect than the native speaker? The problem occurs

because Arab educators and authorities misunderstand the natural function of the

language including written language. The fact is that the average Arabs are pleasantly

surprised and relieved when they encounter a non-native student who is fluent in spoken

Arabic. Immediately, they relax and start to talk normally without any strange mixtures

or unnaturalness. Clearly, Arabs are most comfortable and at ease when speaking in

their native dialect.

Why some Arabs dont like to speak Arabic Historical background

Localism Sectarianism Westernization Tourism and identity crisis

As mentioned earlier, there is a tendency toward localism and sectarianism in Egypt and

Lebanon, which affected the feeling of Arab identity and, included, a willingness to

speak Arabic. Localism in Egypt took the shape of Pharaohnism and became visible in

the late seventies of the twentieth century after the Arab boycott against Egypt and the

suspension of Egyptian membership in the Arab League. That followed the American

sponsored unilateral peace agreement between Egypt and Israel, because it neutralized

Egypt as the largest Arab army against Israel. Localism in Lebanon took the shape of

multiple severe sectarian conflicts: Muslim-Christian, Lebanese-Palestinian, Maronite-

Shiite etc. Sectarian tensions flared in the nineteenth century when Lebanon received

many Christian missionaries from America (Protestant), France (Catholic) and Russia

(Orthodox). Other parts of the Arab world e.g. Syria and Egypt received Christian

missionaries, but no similar success was achieved as occurred in Lebanon. A legacy of

the French colonial period, sectarian division of power gave the Christian Maronite

excessive authority. That helped to cause two bloody civil wars in Lebanon. This led in

turn to a tragedy without precedent when the Maronite party allied with Israel to commit

massacres against the Palestinian-Lebanese in Sabra and Shatila camps, and

slaughtering the person according to ID card.

These examples show how deep and bitter sectarian conflict can be and illustrates the

fragmentation of Arab national identity there, which in turn reflects directly and

negatively on the language. The influx of westernization among Urban Lebanese,

Jordanian and northern Egyptian communities plus the growth of commercial tourism,

particularly in Egypt and Jordan, have caused large number of Arabs to learn English

and come to depend on tourism as source of living. In such an atmosphere, Westerners

studying language and culture have a hard time trying to distinguish themselves from

the flow of generic Western tourists. The students discover that everybody wants to sell

them something and no one is willing to speak Arabic with them. They become a small

minority swimming against the stream. By contrast, the Arab nationalist and/or Islamist

systems, that characterize other parts of the Arab world e.g. Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Sudan

and Libya offer fewer obstacles to the non-native student of Arabic and offer more in

the way of genuine hospitality and generosity.

Arabic for non-natives series-Hussein Maxos: Comparative Studies 1995-2002 IRAMES Group Damascus

Common Misconceptions about spoken - written Arabic:

1. Spoken Arabic is colloquial slang and not spoken in formal communication.

2. Spoken Arabic has no grammar and no rules so it is confusing and useless to

learn.

3. Written Arabic was the spoken language of the medieval golden Arab ages and

it had no dialects, colloquialism nor slang.

4. Arabs from different regions must use written Arabic to communicate, because

they do not understand each others dialects i.e. Libyan speaking to Omani or

Syrian speaking to Yemeni or Sudani.

5. Spoken Arabic is very different and unlike modern written Arabic or the spoken

and written Arabic of medieval times.

6. Spoken Arabic has more foreign influence than written Arabic and came to

existence largely because of the long foreign control over the Arab world.

7. Modern written Arabic is the only correct and pure Arabic and is the same as the

language of the holy Quran. Spoken Arabic is impure and unrelated to the

Quran.

8. Any modernizing or reform of Arabic language aimed at increasing practical

understanding would destroy the beauty and charm of Arabic.

9. The more complicated and rhetorical language an Arab writer or speaker uses,

the better he/she is considered to be.

10. The origin of Arabic is unknown and mysterious and should remain so.

11. Arabic is the most difficult language in the world.

Recommended Solutions: Unity within diversity- Reconciliation

What is called for is, first, an understanding of Arabic based on scientific analysis of the

actual use of the language by the majority of people who speak it. Second, Arab

countries need to promote secular and liberal attitudes that include an in-depth

understanding of the culture, heritage and diversity of the Arab-Islamic-Middle Eastern

society. Third, there is a need for respect and tolerance of the natural function of each

type of language within the ethnic and cultural richness of the region. The result has to

be reconciliation between Spoken and written Arabic, which means reconciliation

between the authority and intellectual elites on one hand and the overwhelming majority

of the Arab people on the other. It also means bridging the gap between past and

present.

Useful tips for non-native students of Arabic:

1. Speak the spoken and use it in speaking. Write the written form (exactly like

what Arabs the native speakers- do).

2. Avoid tourist areas and westernized places, where English or other European

languages are in widespread use.

3. When you notice people talking to you and mixing their language, ask them

politely to speak naturally but slowly.

4. Finish the beginning and intermediate levels of your Arabic course as fast as you

can. The sooner you can begin using spoken Arabic, the more fruitful and

comfortable your experience in the Arab world will definitely be.

5. Do not use the word Ammia for spoken Arabic. It is stigmatic and it will only

remind people of their misconceptions about Arabic. Use Mahki or Lahja

instead, because it is more scientific and neutral.

Arabic for non-natives series-Hussein Maxos: Comparative Studies 1995-2002 IRAMES Group Damascus

6. In order to avoid localist traps that could give wrong information and

interpretation, try to befriend as many people as you can, from all ethnic groups

and make visits to other Arab areas.

7. If possible, pursue your studies outside of urban communities in Egypt, Jordan

and Lebanon (and North Africa) where fewer people speak good English.

8. Speaking with Arabs about Arabic will not help much, but speaking with them

in Arabic about anything else will.

9. These warning words dont and avoid are used here to strengthen your

courage. Being with Arabs is so safe and you always will find it easy to make

friends in the Arab world. Ignore the western media, which is not usually a good

source of information about Arabs.

The Arabic dialectical map: Interrelations and distinctions

Many Arabic dialects are very old, dating back over sixteen centuries and are related to

ancient Semitic languages and dialects, particularly Aramaic. Their distribution is

dependent on demographic factors such as tribal movements and immigration within the

Arab world. For example, the (Imala) pronunciation of the medial letter Alef is the

same in Aleppo and Beirut and the use of the word with the meaning of yet is the

same in Saudi, western Syria and Lebanon. Arab dialects share many key vocabulary

and grammar items compared to written Arabic such as: the simplification of medial

and final hamza, absence of dual (in verbs, nouns, pronouns, demonstrative and

possessive), having one relative pronoun (ten in written), simple negation etc.

The map of spoken Arabic dialects can be approximately drawn to include two major

families of dialects that are divided to other sub-dialects/accents. Geographic,

environmental, economic and ethnic factors play a great role in this dialectical

distribution. The first is the Eastern Mediterranean family that includes northern Egypt,

Lebanon, central and western Syria, Palestine and Jordan. Whats remarkable about this

family is the use of prefix with imperfect verbs and the special pronunciation of the

three letters and . It includes the Urban Eastern Mediterranean (UEM) dialect-

accent, which most non-native students are offered when they decide to learn spoken

Arabic. This sub-dialect comprises the major towns in the countries of the mother

dialect. Probably, the most noticeable difference in UEM is the pronunciation of the

letter as hamza . In general, the pronunciation of the letter in addition to

his/her accent determine where the Arab speaker is from. Another three major accent

distinctions mark the Eastern Mediterranean family as follows: in northern-urban Egypt,

the non-Semitic pronunciation of the letter jeem as g, in central and western

Syria and Lebanon, the pronunciation of the letter qaf like written Arabic (excluding

cities of UEM) and the tone of the feminine T final letter (including UEM). The

second family of dialect is the Bedouin dialects, which stretch from Libya to southern

Egypt, Sudan, Yemen, Saudi and Gulf states, Iraq, part of Jordan to eastern Syria. The

Bedouin dialect family is known for its special pronunciation of the three letters kaf,

qaf and dad and. The non-Semitic pronunciation of the two letters

as ch and g respectively in the Bedouin family is a result of influence from the

neighboring Persian language. The family of Magribi dialects that are used in Tunis,

Algeria, Morocco and Mauritania is not currently included in this map due to lack of

enough information.

Arabic for non-natives series-Hussein Maxos: Comparative Studies 1995-2002 IRAMES Group Damascus

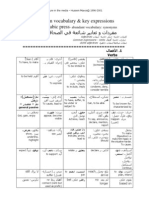

Spoken and Written Arabic on TV and radio broadcasts

Program Spoken Written Notes

News, reports and

analysis

Songs

Interviews

Mixture

Drama, soap opera

and movies

Religion

Children -

cartoons

Average program

i.e. history, sports

etc. (reading)

Average program

(interview)

Press conference

Mostly Written

The division given above is generalized and not strict. Note the following

considerations:

Private TV and radio stations tend to use spoken dialects.

Governmental stations tend to use written Arabic.

Lebanese and Egyptian stations tend to use spoken dialect.

Political and religious programs and stations (Islamic-Christian)

tend to use written Arabic.

Programs with interactive language and live contact tend to use

spoken.

The Spoken pronunciation of certain letters and numbers

are often reflected when reading or pronouncing the Written.

Comparative vocabulary: Accent is the main difference

The division of Arabic vocabulary between spoken and written is so relative that it is

hard to make final judgment about it. The main reason is that spoken Arabic has-like

other languages- a range of formality or informality suitable to the situation and context.

The easily branded vocabulary as spoken only or written only see comparative

vocabulary list- need a special attention because it is not exchangeable in any case

between spoken and written.

This list is also intended to show, how close spoken Arabic really is to written Arabic

and the great similarities among dialects. It is neither final nor comprehensive, but it

gives an idea about some common vocabulary differences. Other vocabulary differences

are directly related to the local environment, including local dress, tools, names of

plants and animals, for example. Other special vocabulary items and a few grammar

points are also necessary to compare. The number of words that vary from dialect to

another is actually rather small in number, when compared to the vast body of Arabic

vocabulary (12 302 912 words). On the other hand, the words that differ tend to be

common, frequent and repetitive vocabulary items e.g. the words for good here

also not speak etc.

You might also like

- (1978) PRUF - A Meaning Representation Language For Natural Languages (Zadeh)Document66 pages(1978) PRUF - A Meaning Representation Language For Natural Languages (Zadeh)Georg OhmNo ratings yet

- Rouchdy Arabic Language in U.S.Document18 pagesRouchdy Arabic Language in U.S.tabouchabkiNo ratings yet

- LINGUACOLONIALISM: SAVE THE AFRICAN SPECIES! by Abajuo Reason EmmaDocument22 pagesLINGUACOLONIALISM: SAVE THE AFRICAN SPECIES! by Abajuo Reason EmmaTrust EmmaNo ratings yet

- A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic - Hans WehrDocument1,130 pagesA Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic - Hans WehrAramide Ghaniyyah100% (1)

- Cracking the Code: The Confused Traveler's Guide to Liberian EnglishFrom EverandCracking the Code: The Confused Traveler's Guide to Liberian EnglishRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Arabic Idioms Part1Document38 pagesArabic Idioms Part1Hussein Maxos50% (2)

- (Template) Personal Writing Regional RubricsDocument15 pages(Template) Personal Writing Regional RubricsRiham AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Fusha andDocument9 pagesFusha andajismandegarNo ratings yet

- Adnan J Almaney - Cultural Traits of The ArabsDocument10 pagesAdnan J Almaney - Cultural Traits of The ArabsHada fadillahNo ratings yet

- Arabic Cultural DayDocument37 pagesArabic Cultural Daywafa sheikhNo ratings yet

- The Arabic Language, Arabic Linguistics and Arabic Computational LinguisticsDocument39 pagesThe Arabic Language, Arabic Linguistics and Arabic Computational LinguisticsMichele EcoNo ratings yet

- Class Module 1 Arabic LanguageDocument11 pagesClass Module 1 Arabic LanguageMess Q. SilvaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Arabic LanguageDocument7 pagesIntroduction To The Arabic LanguageM PNo ratings yet

- Tomastik Karel - Language Policy in MoroccoDocument18 pagesTomastik Karel - Language Policy in MoroccoDjurdjaPavlovicNo ratings yet

- (Ebook-Pdf) The Arabic Language and DialectsDocument24 pages(Ebook-Pdf) The Arabic Language and DialectsChaimae DaintyNo ratings yet

- Arabic LearningDocument81 pagesArabic Learningp_kumar777100% (1)

- English in The Algerian Primary Schools Between Necessity and ContingencyDocument20 pagesEnglish in The Algerian Primary Schools Between Necessity and Contingencynasserreh2017No ratings yet

- The Use of The Mother Tongue in Efl ClasDocument35 pagesThe Use of The Mother Tongue in Efl ClasFernandita Gusweni JayantiNo ratings yet

- MM StokDocument5 pagesMM StokKefan BAONo ratings yet

- Language Attitudes Amazigh in MoroccoDocument57 pagesLanguage Attitudes Amazigh in MoroccoApparel ShopNo ratings yet

- Amar Almasude - The New Mass Media and The Shaping of Amazigh IdentityDocument12 pagesAmar Almasude - The New Mass Media and The Shaping of Amazigh IdentityAhmad MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Thesis Arabic LanguageDocument6 pagesThesis Arabic Languagetjgyhvjef100% (1)

- Berber LangDocument11 pagesBerber LangWriterIncNo ratings yet

- AFRICAN Language SituationDocument8 pagesAFRICAN Language SituationBradNo ratings yet

- Link Outside Newsletter Summer 2018-1Document8 pagesLink Outside Newsletter Summer 2018-1api-526753073No ratings yet

- Cultural Notes EnglishDocument4 pagesCultural Notes EnglishANo ratings yet

- The Weight of English in Global Perspective - The Role of English in IsraelDocument17 pagesThe Weight of English in Global Perspective - The Role of English in IsraelDaniel WeissNo ratings yet

- Why Should I Learn ArabicDocument3 pagesWhy Should I Learn ArabicTomNo ratings yet

- Why Should I Learn ArabicDocument3 pagesWhy Should I Learn ArabicTomNo ratings yet

- GST201-Study Session 5Document14 pagesGST201-Study Session 5Jackson UdumaNo ratings yet

- TamazightDocument14 pagesTamazightSimao BougamaNo ratings yet

- The Hidden Histories of Afrikaans by Hein WillemseDocument13 pagesThe Hidden Histories of Afrikaans by Hein WillemseIvory Platypus100% (1)

- Standarts of English in AfricaDocument27 pagesStandarts of English in AfricaEliane MasonNo ratings yet

- Arabic Language: Historic and Sociolinguistic CharacteristicsDocument10 pagesArabic Language: Historic and Sociolinguistic CharacteristicsJoão GomesNo ratings yet

- Translation in The Arabic of The Middle Ages - OsmanDocument19 pagesTranslation in The Arabic of The Middle Ages - OsmanDonna HallNo ratings yet

- Book Edcoll 9789004300156 B9789004300156 016-PreviewDocument2 pagesBook Edcoll 9789004300156 B9789004300156 016-PreviewsergiusNo ratings yet

- Varieties of ArabicDocument20 pagesVarieties of ArabicMahmoud Sami100% (1)

- Analizing Text of The Language of Al-QuranDocument10 pagesAnalizing Text of The Language of Al-Qurankhoerunnisa budimanNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Language and Lingustics Entry PDFDocument5 pagesEncyclopedia of Language and Lingustics Entry PDFOubaha EnglishNo ratings yet

- Ruba RawashdehhiDocument28 pagesRuba Rawashdehhizaina bookshopNo ratings yet

- Arabic Dialectology PDFDocument26 pagesArabic Dialectology PDFMadalina CiureaNo ratings yet

- Why Study ArabicDocument44 pagesWhy Study ArabicyomnahelmyNo ratings yet

- Developing Resources For Modern South Arabian LanguagesDocument12 pagesDeveloping Resources For Modern South Arabian Languagesme youNo ratings yet

- African Languages An IntroductionDocument14 pagesAfrican Languages An IntroductionDaniel Souza100% (1)

- Arabic Language and Contemporer Civilization (Capturing Arabic Language Roles in Contemporary Era) Gustia TahirDocument10 pagesArabic Language and Contemporer Civilization (Capturing Arabic Language Roles in Contemporary Era) Gustia TahirSaharuddin muinNo ratings yet

- The Berber Speech of Igli Language Towa PDFDocument18 pagesThe Berber Speech of Igli Language Towa PDFStefan MihajlovicNo ratings yet

- Summary of The BA MonographDocument2 pagesSummary of The BA Monographعبد الرحيم فاطمي100% (2)

- Darija-Writing Practices in MoroccoDocument16 pagesDarija-Writing Practices in Moroccoparinde2No ratings yet

- Arabic LangDocument2 pagesArabic LangBarbara RibaričNo ratings yet

- ARA 111 Arabic ConversationDocument87 pagesARA 111 Arabic ConversationWildan SyafiqNo ratings yet

- Aramaic, An Ancient Language Related To Both Hebrew and Arabic, IsDocument2 pagesAramaic, An Ancient Language Related To Both Hebrew and Arabic, IsDiana BarseghyanNo ratings yet

- Islam and Iran A Historical Study of Mutual ServicesDocument24 pagesIslam and Iran A Historical Study of Mutual ServicesAfraNo ratings yet

- The - Discourse of Identity - Jameleddine Ben AbdeljelilDocument4 pagesThe - Discourse of Identity - Jameleddine Ben AbdeljelilJameleddine Ben AbdeljelilNo ratings yet

- Criticism and Theory of Arabic SF: Science Fiction in "Arabic"Document41 pagesCriticism and Theory of Arabic SF: Science Fiction in "Arabic"Abdelhadi EsselamiNo ratings yet

- Arabic Unveiled: A Comprehensive History of the Arabic LanguageFrom EverandArabic Unveiled: A Comprehensive History of the Arabic LanguageNo ratings yet

- From Pharoah's Lips: Ancient Egyptian Language in the Arabic of TodayFrom EverandFrom Pharoah's Lips: Ancient Egyptian Language in the Arabic of TodayNo ratings yet

- Arabic for Beginners: A Guide to Modern Standard Arabic (with Downloadable Flash Cards and Free Online Audio)From EverandArabic for Beginners: A Guide to Modern Standard Arabic (with Downloadable Flash Cards and Free Online Audio)No ratings yet

- Poetic Proverbs2Document22 pagesPoetic Proverbs2Hussein MaxosNo ratings yet

- Arabic Program For Non-Natives Our StrategyDocument6 pagesArabic Program For Non-Natives Our StrategyHussein MaxosNo ratings yet

- مقارنة قواعد comparative Arabic grammarDocument3 pagesمقارنة قواعد comparative Arabic grammarHussein MaxosNo ratings yet

- Key Expressions in Arab PressDocument6 pagesKey Expressions in Arab PressFanis LamakoudisNo ratings yet

- Teaching Listening and SpeakingDocument4 pagesTeaching Listening and SpeakingJan Rich100% (1)

- Karaim LanguageDocument7 pagesKaraim Languagedzimmer6No ratings yet

- Book 8 Grammar Guide: Going To' For The FutureDocument4 pagesBook 8 Grammar Guide: Going To' For The FuturemillemjNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Synonyms and AntonymsDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Synonyms and AntonymsJoshua Gabriel BornalesNo ratings yet

- Milton Model EbookDocument17 pagesMilton Model EbookJustinTangNo ratings yet

- Dyah Indri Fitri Handayani Presented By: Debi Maulana A. H. (2 C)Document16 pagesDyah Indri Fitri Handayani Presented By: Debi Maulana A. H. (2 C)AhsanNo ratings yet

- Elevator Pitch Rubrics (ICT For Social Chnage)Document2 pagesElevator Pitch Rubrics (ICT For Social Chnage)Dran OteroNo ratings yet

- Plan Lectie Used To, Be Used To, Get Used ToDocument2 pagesPlan Lectie Used To, Be Used To, Get Used ToDaniela CiontescuNo ratings yet

- 5TH Sem NotesDocument27 pages5TH Sem NotesMohd yassirNo ratings yet

- High School: San Pablo - Santa Elena - EcuadorDocument2 pagesHigh School: San Pablo - Santa Elena - EcuadorMarcos BernabeNo ratings yet

- TII Workbook Mar20 FINAL PDFDocument342 pagesTII Workbook Mar20 FINAL PDFeverydayisagift9999No ratings yet

- Arabic2-Basics-On-Verbs Final PDFDocument17 pagesArabic2-Basics-On-Verbs Final PDFFahirCanNo ratings yet

- ReflexiveDocument75 pagesReflexiveAlysha Martella100% (4)

- Brazilian TraditionDocument11 pagesBrazilian TraditionPan CatNo ratings yet

- Keynote Int 12.2extension TnotesDocument2 pagesKeynote Int 12.2extension TnotesJulliana SantosNo ratings yet

- Grammar - Vocabulary-Advanced-Grammar-reference-4Document1 pageGrammar - Vocabulary-Advanced-Grammar-reference-4Maria Etelka TothNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Hurt - Injure - Wound - Damage - HarmDocument2 pagesDifference Between Hurt - Injure - Wound - Damage - HarmBulkan_kidNo ratings yet

- Choosing A TopicDocument4 pagesChoosing A Topicmaggu86No ratings yet

- 1A GRAMMAR Verb:, Subject PronounsDocument8 pages1A GRAMMAR Verb:, Subject PronounsThefi BlancoNo ratings yet

- Cartilla de Ingreso A Ingles01Document7 pagesCartilla de Ingreso A Ingles01Yoni LgsmNo ratings yet

- Libro Mi Vida RestanteDocument6 pagesLibro Mi Vida RestanteViri CuevasNo ratings yet

- Bibliography Thesis ExampleDocument5 pagesBibliography Thesis Exampleokxyghxff100% (1)

- The Use of Cue Cards On StudentsDocument5 pagesThe Use of Cue Cards On Studentshidayati shalihahNo ratings yet

- Passive Voice Presentasi Grup 5Document11 pagesPassive Voice Presentasi Grup 5Sandra Pratama100% (1)

- Grade 12 Physical Science Exam Papers and Memos 2015Document2 pagesGrade 12 Physical Science Exam Papers and Memos 2015AngelaNo ratings yet

- Complete Grammar Course 9th. Sem.Document28 pagesComplete Grammar Course 9th. Sem.Diego Ayala100% (1)

- UVT CPEAI-Licenciatura Practice No. 1Document4 pagesUVT CPEAI-Licenciatura Practice No. 1Manolo ReaganNo ratings yet

- O'Grady and Dobrovolsky Eds, 1997 Contemporary Linguistics 3rd EdDocument27 pagesO'Grady and Dobrovolsky Eds, 1997 Contemporary Linguistics 3rd EdLourdes SerrizuelaNo ratings yet