Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Revolutions Reconsidered by Emmett McGregor

Uploaded by

Emmett McGregorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Revolutions Reconsidered by Emmett McGregor

Uploaded by

Emmett McGregorCopyright:

Available Formats

Emmett McGregor MFCO-315 Digital Media and Society Professor Brett Nicholls 30 September, 2011 Revolutions Reconsidered The

documentary series All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace by director Adam Curtis depicts a series of technological and ideological shifts which have deeply impacted society. Foremost among them are the development of computer and network technologies along with the conceptual frameworks brought to the fore by their development. Curtis critiques the failure of the development of global communications networks and computer modeling to improve the freedom and wellbeing of society using the concepts of cybernetics and Objectivism. Though useful these concepts are inadequate to fully describe the historical moments of early Silicon Valley and the eastern European revolutions of the early 2000s. The concept of collective intelligence and structures of molar and molecular communication as proposed by Pierre Lvy demonstrate the failure of information technology pioneers to fully implement their stated dream of an egalitarian network society was not due simply to their ideology or technology, but to a conceptual and practical mishandling of the communication and simulation capacities they created. Furthermore political revolutions in the former soviet states failed not because of the influence of cybernetic systems concepts but because of the underdevelopment of molecular communication within the revolutionary movement as a result of the accelerated speed of the developmental process due to the utilization of instantaneous network communication technologies as described by Paul Virilio. Curtis's depiction of the early development of computer technologies inadequately portrays the diverse field of power relations and ideological underpinnings that accompanied the information technology revolution. Most notably the representatives of the Californian Ideology, a utopian variant of Ayn Rand's Objectivism, from corporate Silicon Valley represent a distinctly hierarchic approach to

development that was directly countered by the early hacker ethic and implementation of open-source development methodology which more effectively implemented individual contributions within an egalitarian framework (Weber, 2004; Himanen, 2001). While the Californian Ideology claims to promote an environment in which a new network society can form unrestrained by government or other regulation, the current state of development within Silicon Valley demonstrates that this ideology was either abandoned shortly after the monetization of the internet became possible, or in fact the Californian Ideologists never truly aspired to an egalitarian society. As Dimitri Kleiner so succinctly states in the Telekommunist Manifesto whether the products of labor are captured by commons-based producers or by capitalist appropriators will determine the kind of society we will have, one based on co-operation and sharing, or one based on force and exploitation, (2010). As their swollen coffers and lofty positions within the capitalist superstructure demonstrate, the supposed Randian Heros of the Californian Ideology have almost unswervingly favored private rather than common modes of distribution. Utilizing the modeling technologies pioneered by these individualists we have attained an unprecedented degree of precision and accuracy, are capable of great economy in processing signs and objects, yet show little concern for systematizing and extending equitable methods of interaction and relation where human beings are involved (Lvy, 1997). Almost universally the proprietary nature of these models has allowed them to be nearly entirely monopolized by corporations concerned primarily with competitive enhancement by means of risk stabilization, governments concerned with maintaining military and ideological dominance over their peers and citizenry, and physical sciences which offer little to the development of new and better social and political paradigms but much to the development of superior technologies of warfare and societal control. Despite the promise of open self-determinate societies used by information technology pioneers to argue for the deregulation of business and technology information technology is used only to rationalize and accelerate bureaucratic performance, rarely to experiment with new forms of organization or innovative, decentralized, flexible, and interactive methods of information processing, (Lvy, 1997).

This failure to open the models to utilization by a public that increasingly has the technological savvy to employ them for their collective benefit amounts to a general front of resistance to the possibility of egalitarian change within the elite of business, government, and military personnel. Such a front asserts the notion that this elite alone holds the capacity to create a vision of the ideal world and the means to implement it. This situation inevitably leads to the forced, final, and externalized nature of a molar solution, an aggregate solution assumed to be valid for everyone, and thus fatally inadequate for anyone. By restricting freedom, totalitarianism destroys the vitality of being. Moreover, the imposition of a perfect world only characterizes a theoretical totalitarianism or, possibly, a technocracy, (Lvy, 1997). Under the guise of creating a more free and open society by utilizing computer models as economic and political stabilizers these powers have in fact pushed representative democracy closer and closer to an undemocratic totalitarian state. National governments have implemented molar means of communication to advance their agenda and underutilized the democratic molecular communication structures made possible by the internet. These states are characterized by the centralization of economic and political power within the hands of a few and a ridged resistance to change outside the parameters of the singular predetermined best of all possible worlds scenario generated using monopolized simulation technologies (Lvy, 1997). This is precisely the conditions which Curtis later describes in the context of the successive economic recessions of the 2000s following the promotion of a model of self-regulating global markets, a historical moment in which power relinquished by the government to nonrepresentative capitalist hierarchies failed to secure the promised economic stability while ensuring these failed institutions were held up at the expense of the mass populace when their vision failed. Curtis implies that the cybernetic model utilized in the conception of global markets has in fact permeated more deeply into the social and cultural consciousness of societies under these markets, and as a result individuals have lost the self-image of empowered democratic citizens. Counter to Curtis's depiction of cybernetics creating disillusionment with the voting process through a new mode of thought, in actuality the effect only amplified an increasing awareness of the inability of the representative

democratic process to adequately express the diversity of opinions and priorities held by the citizenry and to protect those interests from the threat of consolidated power. The concept of a mechanized individual within a political machine more accurately depicts the abstraction of the citizen in the molar electoral process than previous citizen-contributor concepts. This mental shift of the voting constituency parallels Charlie Gere's concept of the abstracted individual under the implementation of computerized governmentality: their individuality is rationalized and normalized in a system of signs that also homogenizes them as a mass, and makes them interchangeable and manipulable as data, (2002). As the mass media has adopted more and more complex modeling for election forecasting the apparent impact of the individual as a unique subjective political participant has been minimized. In the place of this previously glorified citizen-voter has been substituted the concept of the disembodied vote-as-data-point. The act of electoral participation has become a molar process of social regulation in which [a voter's] acts have only a quantitative effect. The individuals who have cast the same ballot in the voting booth are practically interchangeable, even though they are faced with very different problems, even though their arguments and positions are subject to a multitude of slight variations, (Lvy, 1997). Because the models reflect the functional reality of a purely quantitative democratic process the media outlets' predicted results easily pass from being speculatory spectacles to acting simulacra under the model proposed by Baudrillard (1994). The predictive models are projected through the mass media, and voters begin to accept those results as real. Consequently they will be less motivated to actually participate in the electoral process. In effect the media convinces supposed minority voter groups of their failure to effect political change before the democratic process has actually proceeded. Curtis also fails to account for a similar effects of molarity in the eastern European revolutions of the early 2000s. Molecular communication methods were utilized to organize the insurrections themselves in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan. Individuals contacted one another on a one-to-one or small group basis in order to evade detection by the state utilizing networked communication pathways, however in the ensuing action the mass media took ahold of much of the communication between the revolutionaries

and the outside world, as well as between the revolutionaries and the mass populace of their constituent countries. Curtis suggests that the revolutions failed to increase the actual freedom of the populace because they were operating under the ideological framework of self-regulating systems and that their utilization of networked communications was only enough to facilitate reactionary short-term actions. Lvy's concept of molar and molecular communication indicates that this failure to substantiate actual change was not necessarily an ideological gap, however, but rather a failure to establish a sustained framework of molecular communication and direct democracy that would have built upon the mechanisms used to actualize the revolutionary moment to construct a more free society (Lvy, 1997). This failure can be partially attributed to the suppression of discussions concerning alternative government structures by the overthrown government in the years preceding the revolutions, with what few resources on democracy that were available almost certainly having been filtered through the same mass media that would later fail to accurately depict the opportunity for reform and popular empowerment in the period following the revolutions. No regime is completely effective at suppressing information in this age of infinite reproducibility, however, and other factors must have contributed. Virilio's concept of speed as an antagonistic condition of the digital media environment serves to shed light on several other possible contributing elements to the failure of the revolutions (1998). First is the simple duration of the revolutionary struggle. Previous revolutions had by necessity involved lengthy periods of clandestine ideological communication, the formation of sleeper cells, underground communications networks, revolutionary vanguards, and other organizational structures utilized in the effective military overthrow of a government which necessitated extended deliberation and drive for consensus. As Lvy states It takes time to learn, to think, to innovate, to make decisions as a group. It requires even more time to form judgements collectively, adjust and deploy languages, knit a community together, (Lvy, 1997). In the case of the first internet-enabled resistance movements, these former necessities were hugely reduced, if not simply done away with, as the planning phase of the revolutionary moment was accelerated to a pace at which consensus about the singular issue of the necessity to

overthrow the government could be reached and acted upon without fully engaging in the deliberatory processes that create a foundation for post-revolutionary government. As a result a revolutionary community which could effectively manage the post-revolutionary moment never fully developed. The single mutual judgement, that the previous government had failed to deliver the freedom the population demanded, was not alone enough to create a mutual base of judgement, values, and language to effectively craft the social and governmental structures of free democracies. What ties are made within the network-enabled opposition movement are undermined by the collapse of intimacy at a distance after the revolutionary moment (Virilio, 1998). The apparent freedom and ease of establishing political ties at a distance within networked communications fail to account for the necessity for local actualization of the revolutionary ideology. Under longer timeframes each individual could voice the needs and desires of their respective communities in order to construct a greater picture of how the achieved freedom should be maintained, but at the pace at which the eastern European revolutions took place no such molecular interactions could take place. Instead the generalized and unspecific demands for freedom and democracy served as talking points for a revolution out of touch with its constituent communities. The failure to recognize and reconcile regional and local difference is accepted as part of the necessary cosmopolitanism of a movement that communicates and acts at speed. The cosmopolitanization of the revolution serves to render difficult if not impossible the construction of united political fronts with clearly declared objectives for the establishment of a new governmental order (Virilio, 1998). Near instantaneous communication between the constituent individuals of the revolution served to greatly increase their ability to freely express their dissent on a surface level while paradoxically undermining the effectiveness of their liberating exercise due to a failure to develop and implement a post-revolutionary plan of action. The momentary freedom of a revolution at speed quickly recedes after the reassertion of preexisting power structures to fill the governmental vacuums left in their wake. The molar mass media helps to assure that the revolutionaries

will lose their momentary foothold in the power relations of government by celebratory crying of the victory of the revolution and simplifying its context to the point where it appears the transitionary process has concluded and freedom is secured (Lvy, 1997). In actuality this moment, more than the overthrow of the government, represents the most essential period of the revolutionary struggle. The resulting lack of popular inertia for the construction of new governmental structures combines with the speed-driven lack of planning and development within the revolutionary community assure the revolution is abortive, soon returning to the status quo of tyranny and stifled freedoms. The combined failure of the network revolution and network-enabled revolutions of the late 20th and early 21st centuries demonstrate the range of obstacles in creating and implementing egalitarian political and social frameworks within context of a newly networked world. Curtis attributes these failures to a rise in the ideology of self-sustaining cybernetic systems and objectivist domination of the financial sector. A more complete analysis concludes that the failure of network pioneers to assure open egalitarian application of new computer modeling and instantaneous group communication technologies, as well as the persistence of structures of molar mass media as described by Lvy in combination with the effects of Virilio's speed concept on the developmental cycle of the revolutionary moment have undermined the empowering aspects of computer information technologies. While All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace concludes with open-ended pessimism as to the prospect of popular empowerment through recent technological developments, this analysis leaves open the possibility of future applications of these technologies accounting for and overcoming the outlined challenges. As the aftermath of the recent Arab Spring revolutions continues to unfold and internet services such as wikipedia, kickstarter, and other collaborative platforms more fully develop the promises of digital revolution may yet be fulfilled. Works Cited Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation (S. Glaser, Trans.). Ann Arbor, MI: Univ of Michigan Pr. (Original work published 1981)

Curtis, A. (Director). (2011). All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace [Television Series]. London: BBC 2. Gere, C. (2002). Digital Culture (pp. 17-41). London: Reaktin Books. Kleiner, D. (2010). The Telekommunist Manifesto. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures. Lvy, P. (1997). Collective Intelligence: Mankind's Emerging World in Cyberspace (pp. 39-89). New York: Plenum Trade. Virilio, P. (1998). The State of Emergency. In J. Der Derian (Ed.), The Virilio Reader (pp. 46-57). London: Blackwell.

Citation style drawn from http://myrin.ursinus.edu/help/resrch_guides/cit_style_apa.htm#book_translation and http://myrin.ursinus.edu/help/resrch_guides/cit_style_apa.htm#book_translation

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Manual de TallerDocument252 pagesManual de TallerEdison RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Fiesta Mk6 EnglishDocument193 pagesFiesta Mk6 EnglishStoicaAlexandru100% (2)

- Sa 449Document8 pagesSa 449Widya widya100% (1)

- CV - Shakir Alhitari - HR ManagerDocument3 pagesCV - Shakir Alhitari - HR ManagerAnonymous WU31onNo ratings yet

- 5.pipeline SimulationDocument33 pages5.pipeline Simulationcali89No ratings yet

- Centaour 50 Solar TurbineDocument2 pagesCentaour 50 Solar TurbineTifano KhristiyantoNo ratings yet

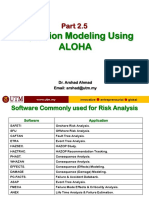

- PLSP 2 6 Aloha PDFDocument35 pagesPLSP 2 6 Aloha PDFKajenNo ratings yet

- NORSOK Standard D-010 Rev 4Document224 pagesNORSOK Standard D-010 Rev 4Ørjan Bustnes100% (7)

- Assessment of Learning 1 Quiz 1Document3 pagesAssessment of Learning 1 Quiz 1imalwaysmarked100% (4)

- Facility Layout Case StudyDocument8 pagesFacility Layout Case StudyHitesh SinglaNo ratings yet

- Slag Pot DesignDocument2 pagesSlag Pot Designnitesh1mishra100% (2)

- Economics Case StudyDocument28 pagesEconomics Case StudyZehra KHanNo ratings yet

- Lancaster LinksDocument3 pagesLancaster LinksTiago FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Amendment No. 3 June 2018 TO Is 15658: 2006 Precast Concrete Blocks For Paving - SpecificationDocument3 pagesAmendment No. 3 June 2018 TO Is 15658: 2006 Precast Concrete Blocks For Paving - Specificationraviteja036No ratings yet

- Bhavin Desai ResumeDocument5 pagesBhavin Desai Resumegabbu_No ratings yet

- Riviera Sponsorship LetterDocument7 pagesRiviera Sponsorship LetterAnirudh Reddy YalalaNo ratings yet

- CeldekDocument2 pagesCeldekPK SinghNo ratings yet

- Dutch Cone Penetrometer Test: Sondir NoDocument3 pagesDutch Cone Penetrometer Test: Sondir NoAngga ArifiantoNo ratings yet

- Pd-Coated Wire Bonding Technology - Chip Design, Process Optimization, Production Qualification and Reliability Test For HIgh Reliability Semiconductor DevicesDocument8 pagesPd-Coated Wire Bonding Technology - Chip Design, Process Optimization, Production Qualification and Reliability Test For HIgh Reliability Semiconductor Devicescrazyclown333100% (1)

- Manual Instructions For Using Biometric DevicesDocument6 pagesManual Instructions For Using Biometric DevicesramunagatiNo ratings yet

- JUNOS Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesJUNOS Cheat SheetJaeson VelascoNo ratings yet

- Colebrook EquationDocument3 pagesColebrook EquationMuhammad Ghufran KhanNo ratings yet

- Thrust Bearing Design GuideDocument56 pagesThrust Bearing Design Guidebladimir moraNo ratings yet

- R Values For Z PurlinsDocument71 pagesR Values For Z PurlinsJohn TreffNo ratings yet

- Procedimiento de Test & Pruebas Hidrostaticas M40339-Ppu-R10 HCL / Dosing Pumps Rev.0Document13 pagesProcedimiento de Test & Pruebas Hidrostaticas M40339-Ppu-R10 HCL / Dosing Pumps Rev.0José Angel TorrealbaNo ratings yet

- Bubble Point Temperature - Ideal Gas - Ideal Liquid: TrialDocument4 pagesBubble Point Temperature - Ideal Gas - Ideal Liquid: TrialNur Dewi PusporiniNo ratings yet

- CL21C650MLMXZD PDFDocument45 pagesCL21C650MLMXZD PDFJone Ferreira Dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Open XPS Support in Windows 8: WhitePaperDocument24 pagesOpen XPS Support in Windows 8: WhitePaperDeepak Gupta (DG)No ratings yet

- Vatan Katalog 2014Document98 pagesVatan Katalog 2014rasko65No ratings yet

- Plastiment BV 40: Water-Reducing Plasticiser For High Mechanical StrengthDocument3 pagesPlastiment BV 40: Water-Reducing Plasticiser For High Mechanical StrengthacarisimovicNo ratings yet