Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Untitled

Uploaded by

prasanth_raj_2Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Untitled

Uploaded by

prasanth_raj_2Copyright:

Available Formats

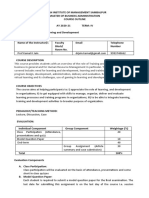

MAN 283.16: LEADING PEOPLE AND ORGANIZATIONS SPRING 2012 Professor John W. Burrows, Ph.D. Office CBA 3.

238 Phone 232-5655 (office) 740-2839 (cell before 9pm) E-Mail John.Burrows@mccombs.utexas.edu Course Web Page via Blac board ________________________________________________________________________________ ___________ Course Description Leading individuals, groups, and organizations effectively is the ey to manager ial excellence. Yet, it could be your most difficult challenge as a manager. Thi s course is designed to help you meet this challenge. The course aims to develop and sharpen nowledge and s ills that are essential to designing and managing o rganizations to elicit the best out of their human resources. In the course we will tie concrete organizational situations (as reflected in ca ses and simulations) to essential theories and principles of effective managemen t. The topics are organized into two broad categories: The first several session s focus on macro aspects, and include topics at the organizational level of analys is. The remaining sessions focus on micro aspects of managing individuals in organ izations, and include topics at the individual and group levels of analysis. Eac h of the topics covered in the course provides a unique perspective on understan ding and shaping behavior in organizations. We will loo at how these perspectiv es can be used as a lever to wor in, lead and transform organizations. Learning Goals To provide students with a perspective on how to lead and transform organization s through people using conceptual nowledge, case studies, and experiential exer cises. To facilitate an exchange of ideas and experiences in the classroom conducive to learning about organizational behaviour. To enhance critical and integrative thin ing about business issues: Students wil l develop and enhance their s ills in identifying ey issues in a business setti ng, developing a perspective that is supported with relevant information and int egrative thin ing, and drawing and assessing conclusions. To enhance capabilities for interpersonal awareness and wor ing in teams: Throug h both the content covered and through team wor inside and outside the classroo m, students will develop and strengthen their abilities to wor effectively in t eams, their understanding of the importance of individual roles and tas s in tea ms, and their abilities to manage conflict and collaboration in the interest of achieving team goals.

COURSE Course Total 1. 20% 2. 35% 3.

REQUIREMENTS: Requirements and Grading Two group case evaluations (10% each) Final exam Leadership project (group or individual; due November 17th)

Required Readings Required readings are in the course pac ssessments set for the course.

and should suffice to prepare for the a

20% 4. 25%

Individual class contribution

Description of Requirements 1. Group Case Evaluations For each group case evaluation, your deliverable is a 3-page (12 point Times New Roman font, double spaced, 1-inch margins) written assessment of a case using q uestions that will be provided for the session and the bac ground reading for th e session (format: please present your write-up in the form of answers to the ca se questions). No late submissions will be accepted. Please submit a copy of you r case write-up on Blac board. 2. Final Exam The final exam will cover the assigned readings, any additional hand-outs, lectu res, class discussions, and exercises. The exam will test your nowledge of theo ries and concepts as well as your understanding of how these theories and concep ts apply to organizational situations. Additional instructions for the exam will be provided in class. 3. Leadership Project You are responsible for 6 - 8 interviews with people you consider to be highly e ffective leaders. The persons selected might be business leaders, government lea ders, community leaders, and/or religious leaders. My preference is for you to c ontact EMBA alumni, but feel free to use others if they would be of better benef it to your project and/ or career. My only requirement is that you cannot now y our interviewees in advance. You will be interviewing your selected leaders about their personal philosophies of leadership, their most significant developmental experiences, the s ills and actions they most depend on as leaders, and their recommendations for students o f leadership. Given that you will be investing a fair amount of time and energy s tudying the results from these interviews, please select the interviewees wisely . You might find the following questions a useful starting place for the interview s: How do you define leadership? As a leader, what are the personal s ills and actions on which you most depend? Do you thin that leadership effectiveness can develop with experience? What are the two or three experiences that you remember as being most influentia l in developing your leadership s ills? What made these experiences so valuable for you? What role do personal values and ethics play in your leadership effectiveness? Do you thin that leadership in your arena (e.g., business, politics, etc.) is d ifferent from, or involves different pressures and s ills, than leadership in ot her arenas? What advice would you offer others who are trying to develop their leadership ef fectiveness? How do you ensure that your organization is developing the leaders that it needs ? Once all of the interviews have been conducted, search the content of the interv iews for commonalties or themes. What can be learned from the leaders? How does the data from the interviews compare to what is discussed in class and what you are exposed to in our readings? Prepare a report on what you feel can be learned from the leaders you interviewe d. The report should include all of the major learnings that resulted from both

the interviews as well as an integration of these learnings into class readings and discussions. In addition, the following questions should be addressed: How were the leaders in your interview sample selected? What were the themes and ey learnings that your team extracted from the intervi ews? What are the principle learning points that students of leadership should ta e f rom the interviews with your selected leaders? What lessons, in terms of our ow n leadership development, should we extract? Your report should contain a model of your own creation which captures what you feel to be the critical aspects of leadership as indicated by (1) your leadershi p interviews, (2) your own VABES, and (3) class readings. Do not underestimate h ow long it ta es to thoughtfully complete a model that is consistent with and su pported by 1, 2, &3, which, if not adequately developed, will lead to a wea arg ument for your model. 4. Individual Class Contribution You are expected to read the case(s) and reading(s) for each class session befor e class. I will cold call on students to present facts from the cases/readings, opinions, etc. Your class contribution grade will be negatively affected by answ ers which demonstrate a lac of preparation for class. Note that there is no fix ed number of times that a person may be called on during the semester. Your contribution to class discussions will be graded as follows Grade Achievement A Contributions in class reflect exceptional preparation. Ideas of fered are always substantive, provide one or more major insights as well as dire ction for the class. Challenges are well substantiated and persuasively presente d. If this person were not a member of the class, the quality of discussion woul d be diminished mar edly. B Contributions in class reflect satisfactory preparation. Ideas o ffered are sometimes substantive, provide generally useful insights but seldom o ffer a new direction for the discussion. Challenges are sometimes presented, fai rly well substantiated, and are sometimes persuasive. If this person were not a member of the class, the quality of discussion would be diminished somewhat.. C This person says little or nothing in class. Hence, there is not an adequate basis for evaluation. If this person were not a member of the class , the quality of discussion would not be changed. D Contributions in class reflect inadequate preparation. Ideas off ered are seldom substantive, provide few if any insights and never a constructiv e direction for the class. Integrative comments and effective challenges are abs ent. If this person were not a member of the class, valuable air-time would be s aved. For the learning process to be effective, you will need to prepare carefully bef ore class and contribute actively during class. Preparation involves both thorou gh analysis and developing a personal position on issues raised in the cases and readings. Unless you have thought about and adopted a personal position, it is very hard to learn from others contributions in the class. This does not mean th at you have solved the case, in the sense that you have identified the one best an swer to the issues facing the firms and managers in the case. Invariably, given the complexities of people and situations in the real world, there is no single answer. Instead, thorough preparation means that you read the materials, conside r the issues raised by the case and assignment questions, and carry out appropri ate analysis in order to arrive at a thoughtful position concerning the options that face the firms and managers in the case. By actively participating in class discussions, you will sharpen your own insights and those of your classmates. Conversation Guidelines : i. Listen before you spea . Polite conversationalists do not wal up to a g

roup and begin tal ing. Even if they are quite familiar with the individuals the y approach they wait to find out what is being discussed at the moment. Ma e ge nuine connections with the important points being made. We are not in conversat ion mode when we forget to ta e seriously what has already been said. ii. Connect with points already made. Inept conversationalists ma e a passin g reference to the current conversation, but move quic ly to what they had on th eir minds before joining the group. The more interesting conversationalist conti nues to ma e genuine lin s to the ideas of others. As a result, the content they intend to share upon arrival is shaped by the conversation, and shapes the conv ersation. By extension, the generation of new ideas that could only have come fr om engaging with others is the sign of successful conversation. iii. Be interesting. We dont listen long to those who repeat previous points i n a conversation or are tangential to the main thread of conversation. The good conversationalist thin s about people he or she is tal ing to, considers what wo uld interest them, edits content to ma e sure that these connections are clear, and then says something the others have not thought of before. Consider if you w ere spea ing to people you would most li e to meet. If you were luc y enough to meet an author in the conversation that interests you, you would not be complet ely tongue-tied, but would wor hard to thin of the most interesting thing you could say. You would try to avoid saying what they already now. iv. Be self-critical. Be critical in your thin ing and in your comments, but also try and be constructive and respectful of different points of view (even w hen you strongly disagree). v. Substantiate your ideas. Quality of contributions is what matters, not q uantity. When you ma e a statement, be sure you can substantiate and support you r statementthis is more important than being right or wrong. Some of the things that have an impact on effective class contribution are the f ollowing: No single individual should dominate the discussion. Ma e your points, and then let others have a chance to ma e theirs. An equal time rule will be in effect. Is the contributor a good listener? (e.g., a sign is whether the person merely r epeats what others have just said) Is the contributor willing to interact with other class members? Are the points that are made relevant to the discussion? Are they lin ed to the comments of others? Are they lin ed to current or past course material? Do the comments add to our understanding of the situation? Does the contributor distinguish between different inds of data (i.e., facts, o pinions, beliefs, concepts, etc.)? Is there a willingness to test new ideas, or are all comments, safe? For example, repetition of case facts without analysis and conclusions. Can the contributor substantiate and support his/her statements? Are the comments critical, but also constructive and respectful of different poi nts of view (even when you strongly disagree)? Late Assignment Policy Any assignment that is late will have points deducted. Assignments will be pena lized 25% for each day they are late, beginning after attendance has been ta en on the day it is due. No paper will be accepted after it is 1 wee late. McCombs Classroom Professionalism Policy The highest professional standards are expected of all members of the McCombs co mmunity. The collective class reputation and the value of the Texas MBA experien ce hinges on this. Faculty are expected to be professional and prepared to deliver value for each a nd every class session. Students are expected to be professional in all respects . The Texas MBA classroom experience is enhanced when: **Laptops are closed and put away**. When students are surfing the web, respondi ng to e-mail, instant messaging each other, and otherwise not devoting their ful l attention to the topic at hand they are doing themselves and their peers a maj

or disservice. Those around them face additional distraction. Fellow students ca nnot benefit from the insights of the students who are not engaged. My office ho urs are spent going over class material with students who chose not to pay atten tion, rather than truly adding value by helping students who want a better under standing of the material or want to explore the issues in more depth. Students w ith real needs may not be able to obtain adequate help if my time is spent repea ting what I said in class. There are often cases where learning is enhanced by t he use of laptops in class. I will let you now when it is appropriate to use th em. In such cases, professional behavior is exhibited when misuse does not ta e place. Students arrive on time. On time arrival ensures that classes are able to start and finish at the scheduled time. On time arrival shows respect for both fellow students and faculty and it enhances learning by reducing avoidable distractions . Students display their name cards. This permits fellow students and faculty to l earn names, enhancing opportunities for community building and evaluation of inclass contributions. Students minimize unscheduled personal brea s. The learning environment improves when disruptions are limited. Students are fully prepared for each class. Much of the learning in the Texas MB A program ta es place during classroom discussions. When students are not prepar ed they cannot contribute to the overall learning process. This affects not only the individual, but their peers who count on them, as well. Students respect the views and opinions of their colleagues. Disagreement and de bate are encouraged. Intolerance for the views of others is unacceptable. Phones and wireless devices are turned off. Weve all heard the annoying ringing i n the middle of a meeting. Not only is it not professional, it cuts off the flow of discussion when the search for the offender begins. When a true need to comm unicate with someone outside of class exists (e.g., for some medical need) pleas e inform the professor prior to class. Remember, you are competing for the best faculty McCombs has to offer. Your prof essionalism and activity in class contributes to your success in attracting the best faculty to this program. Academic Dishonesty I have no tolerance for acts of academic dishonesty. Such acts damage the reput ation of the school and the degree and demean the honest efforts of the majority of students. The minimum penalty for an act of academic dishonesty will be a z ero for that assignment or exam. The responsibilities for both students and fac ulty with regard to the Honor System are described on http://mba.mccombs.utexas. edu/students/academics/honor/index.asp and on the final pages of this syllabus. As the instructor for this course, I agree to observe all the faculty responsib ilities described therein. During Orientation, you signed the Honor Code Pledge. In doing so, you agreed to observe all of the student responsibilities of the H onor Code. If the application of the Honor System to this class and its assignme nts is unclear in any way, it is your responsibility to as me for clarification . Please ma e sure you are aware of the different expectations between individual and team assignments. Students with Disabilities Upon request, the University of Texas at Austin provides appropriate academic ac commodations for qualified students with disabilities. Services for Students wit h Disabilities (SSD) is housed in the Office of the Dean of Students, located on the fourth floor of the Student Services Building. Information on how to regist er, downloadable forms, including guidelines for documentation, accommodation re quest letters, and releases of information are available online at http://deanof students.utexas.edu/ssd/index.php . Please do not hesitate to contact SSD at (51 2) 471-6259, VP: (512) 232-2937 or via e-mail if you have any questions.

Sugestions: To stimulate your own learning, consider that one learns best that w hich one teaches oneself. In that spirit, to get the most out of the readings, I suggest the following 1. Read the case quic ly, to get the gist of the problem, then read it agai n, more slowly, mar ing important facts and details that might influence your th in ing. 2. On a separate sheet of paper, ma e some notes about the problem, actions you would suggest, and beginning answers to the study questions provided. 3. Tuc your notes away and read the readings associated with the case. 4. Reflect on the case in light of the readings and add more substance to # 2 above. 5. Discuss the case with others in the class and add even more substance to #2 above. Topic Saturday, January 7 Introduction to Leadership Case 1. Coach Knight and Coach K (In class video case. No preparation necessary. ) 2. Edward Norris and the Baltimore Police Department a) Why is this case/situation important to businesspeople? b) Given the conditions in Baltimore at the time, would you have ta en this job? Why or why not? c) If you had ta en the job, what would you have done and why? Be specific and detailed.

Topic Friday, January 20 Structure: Structuring Organizations for Optimal Performance Case: 1. a. b. e? c. Appex Corp What challenges did Ghosh face when he joined Appex? What problems did each new structure address? What problems did it creat What would you have done in Ghoshs place?

2. ABB a. Why did Barnevi choose such a complex organizational form after so many global matrix structures failed in the past (Corning, Citiban , Westinghouse, ) b. From what you have seen in the case, what does it ta e for such an organ ization to succeed? c. How has structure shaped the roles and responsibilities of ey front-lin e, senior, and executive managers in the case? How has it effected Don Jans tas s as a front-line manager? What are the core responsibilities of Bar er and Gunde mar as senior managers in ABB? And what ey roles does Lindahl have as one of t he top executives? d. If Percy Barnevi were to read this case, do you thin he would have bee n pleased or disappointed with the way things are wor ing in the global relays b usiness? What changes, if any, might he want to ma e in his companys structure, s ystems, shared values, s ills, etc.? Reading: 1. A Note on Organizational Structure 2. Do You Have a Well Designed Organization Topic Friday, February 3 Shared Values: Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture Case:

1. Four Seasons Goes to Paris a. What is it li e to stay at the Four Seasons? b. What has made the Four Seasons so successful over the last 30 years? c. Does culture play a role in the Four Seasons success? If so, how and why ? d. What do you thin about the way the Four Seasons entered the Paris/French mar et? What was good/bad about their entry strategy? 2. Home Depot s Blueprint for Leveraging Cultural Change Reading: 1. Leading By Leveraging Culture 2. Renovating Home Depot Case: 1. Home Depot s Blueprint for Leveraging Cultural Change Reading: 1. (Optional) Renovating Home Depot

Topic Saturday, February 4 Systems: HR and Motivation Case: 1. GEs Talent Machine: The Ma ing of a CEO a. While most companies have difficulties producing enough quality talent, what philosophies, policies, and practices have allowed GE to produce a surplus? b. As Jeff Immelt, how would you deal with the proposals to change the vita lity curve, MBA and international recruitment, and the executive bands? c. What lessons have you learned from this case? Reflecting on your analysi s positive or negativeof GEs development of its management pipeline, what do you se e as the ey success factors in ma ing talent management what Immelt claims is a n important source of GEs competitive advantage? Reading: 1. A Players" or "A Positions"? The Strategic Logic of Wor force Management. Case: 1. Lincoln Electric (In class video case. No preparation necessary.) 2. SAS (In class video case. No preparation necessary.) Reading: 1. What Motivates Employees According to Over 40 Years of Motivation Survey s 2. Motivating People from Around the World GROUP CASE ANALYSIS ON GE DUE

Topic Friday, February 17 Strategy: Leading Change Reading: 1. GlobalTech Players Guide 2. GlobalTeach Change Theory In-Class Computer Simulation: 1. Global Tech

Topic Friday, March 2 Staffing: Designing and Leading Teams Case: 1. Medisys

a. How well is this team performing, and why? What factors are posing chall enges to the team? b. What should Merz do? Reading: 1. Leading Teams Case: 1. Managing a global team: Greg James at Sun Microsystems, Inc. a. What are the problems facing the global team? b. What is at the root of the problems? c. What should Greg James do? Reading: 1. Can absence ma e a team grow stronger? 2. Managing multicultural teams

Topic Saturday, March 3 Staffing: Designing and Leading Teams Case: 1. Mount Everest (1996) a. What is the root cause of the disaster? b. Are tragedies li e this simply inevitable in a place li e Everest? c. What is your evaluation of Scott Fischer and Rob Hall as leaders? Did th ey ma e some poor decisions? If so, WHY? d. What are the lessons from this case for general managers in business ent erprises? Readings: 1. Before You Ma e That Big Decision 2. Leading Teams GROUP CASE ANALYSIS ON EVEREST DUE Topic Saturday, March 17 Style: Motivating Superior Performance (Micro) Case: 1. John Wolford a. What are the problems here? b. Why does John behave the way he does? c. If you were in Lutz position, what would you do? Why? Reading: 1. Why People Behave the Way They Do Role Play: 1. The Use of Force a. Who are the ey sta eholders in the Use of Force? b. If you were on the NY state medical examining board, what would you do w ith the doctor? c. Why was this assigned in business school? 2. Richard Chamberlain (In class; no preparation necessary) Case: 1. Tough Guy a. What are Fraziers options? What will wor ? What wont? Why? b. Why are there Mazeys in business? Why do they get ahead? How can you man age them when you report to them? How can you manage them when they report to yo u?

Topic Saturday, March 31 Style: Leading Yourself Case: 1. Japanese Leadership: the Case of Tetsundo Iwa uni a. What were the ey events in Iwa unis life that influenced his thin ing? b. What traditional barriers did he brea to try to create a new environmen t? c. What aspects of Iwa unis leadership style to you admire? Disli e? d. Which of the strategic thin ing framewor s if any did Iwa uni seem to em ploy? e. Be prepared to present your diagrammatic model of Iwa unis leadership per spective. f. What inds of traditions do you find troublesome or would you li e to se e changed? Reading: 1. Strategic Frames Case: 1. The Life and Career of a Divisional CEO: Bob Johnson at Honeywell (A) a. What do you find noteworthy about Bobs life and career? b. Compare Bob with Tetsundo. How are they the same/different? c. What does it ta e to be CEO? Assignment: 1. Write your life story and bring a hard copy to class. You can use Jimmy Buffetts as a model for format if you wish. Style: Leading Yourself Case: 2. Japanese Leadership: the Case of Tetsundo Iwa uni g. What were the ey events in Iwa unis life that influenced his thin ing? h. What traditional barriers did he brea to try to create a new environmen t? i. What aspects of Iwa unis leadership style to you admire? Disli e? j. Which of the strategic thin ing framewor s if any did Iwa uni seem to em ploy? . Be prepared to present your diagrammatic model of Iwa unis leadership per spective. l. What inds of traditions do you find troublesome or would you li e to se e changed? Reading: 2. Strategic Frames Case: 2. a. b. c. The Life and Career of a Divisional CEO: Bob Johnson at Honeywell (A) What do you find noteworthy about Bobs life and career? Compare Bob with Tetsundo. How are they the same/different? What does it ta e to be CEO?

Assignment: 2. Write your life story and bring a hard copy to class. You can use Jimmy Buffetts as a model for format if you wish. DUE: Leadership Project Topic Friday, April 13th

Friday the 13th: The Most Enjoyably Rigorous Cumulative Final Exam Ever (Sample questions are on Blac board)

Biographical Note Dr. John Burrows received his undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt in 1988. Foll owing graduation he moved to Germany to wor for Ingenieurbro Glc l in Munich as a financial analyst for development projects with the United Nations Industrial D evelopment Organization (UNIDO). He was responsible for projects in Ethiopia (in frastructure), Ghana (food and beverage), China (medical device manufacturing), Mauretania (ban ing), and the former East Germany (consumer products), among oth ers. While at Ingenieurbro Glc l Dr. Burrows also managed joint ventures between organi zations in Western and Eastern Europe. New companies were founded in Poland (con struction supplies), Tur ey (entertainment), Yugoslavia (food and beverage), and Russia (consumer products). Fascinated by life in East Germany, he too a job with Ernst & Young in Leipzig, Germany soon after the fall of the Berlin wall. He conducted mergers and acquis itions of the former East German conglomerates in the food and beverage, oil and gas, and consumer products industries. In 1994 he moved bac home to Austin and joined Dell Computer Corporation as it became a global corporation. He was responsible for financial systems in Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Australia, Korea, and Vietnam. Since earning his PhD from Tulane University, he has received four teaching awar ds in the last six hears. He currently teaches leadership, negotiation, and mana ging teams. Dr. Burrows is a spea er at numerous industry and organizational con ferences, and his published wor in cross-cultural leadership has received accol ades from the Academy of Management and the Society for Industrial and Organizat ional Psychologists. Honor Code Purpose Academic honor, trust and integrity are fundamental to The University of Texas a t Austin McCombs School of Business community. They contribute directly to the q uality of your education and reach far beyond the campus to your overall standin g within the business community. The University of Texas at Austin McCombs Schoo l of Business Honor System promotes academic honor, trust and integrity througho ut the Graduate School of Business. The Honor System relies upon The University of Texas Student Standards of Conduct (Chapter 11 of the Institutional Rules on Student Service and Activities) for enforcement, but promotes ideals that are hi gher than merely enforceable standards. Every student is responsible for underst anding and abiding by the provisions of the Honor System and the University of T exas Student Standards of Conduct. The University expects all students to obey t he law, show respect for other members of the university community, perform cont ractual obligations, maintain absolute integrity and the highest standard of ind ividual honor in scholastic wor , and observe the highest standards of conduct. Ignorance of the Honor System or The University of Texas Student Standards of Co nduct is not an acceptable excuse for violations under any circumstances. The effectiveness of the Honor System results solely from the wholehearted and u ncompromising support of each member of the Graduate School of Business communit y. Each member must abide by the Honor System and must be intolerant of any viol ations. The system is only as effective as you ma e it. Faculty Involvement in the Honor System The University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business Faculty s commitmen

t to the Honor System is critical to its success. It is imperative that faculty ma e their expectations clear to all students. They must also respond to accusat ions of cheating or other misconduct by students in a timely, discrete and fair manner. We urge faculty members to promote awareness of the importance of integr ity through in-class discussions and assignments throughout the semester. Expectations Under the Honor System Standards If a student is uncertain about the standards of conduct in a particular setting , he or she should as the relevant faculty member for clarification to ensure h is or her conduct falls within the expected scope of honor, trust and integrity as promoted by the Honor System. This applies to all tests, papers and group and individual wor . Questions about appropriate behavior during the job search sho uld be addressed to a professional member of the Career Services Office. Below a re some of the specific examples of violations of the Honor System. Lying Lying is any deliberate attempt to deceive another by stating an untruth, or by any direct form of communication to include the telling of a partial truth. Lyin g includes the use or omission of any information with the intent to deceive or mislead. Examples of lying include, but are not limited to, providing a false ex cuse for why a test was missed or presenting false information to a recruiter. Stealing Stealing is wrongfully ta ing, obtaining, withholding, defacing or destroying an y person s money, personal property, article or service, under any circumstances . Examples of stealing include, but are not limited to, removing course material from the library or hiding it from others, removing material from another perso n s mail folder, securing for one s self unattended items such as calculators, b oo s, boo bags or other personal property. Another form of stealing is the dupl ication of copyrighted material beyond the reasonable bounds of "fair use." Defa cing (e.g., "mar ing up" or highlighting) library boo s is also considered steal ing, because, through a willful act, the value of another s property is decrease d. (See the appendix for a detailed explanation of "fair use.") Cheating Cheating is wrongfully and unfairly acting out of self-interest for personal gai n by see ing or accepting an unauthorized advantage over one s peers. Examples i nclude, but are not limited to, obtaining questions or answers to tests or quizz es, and getting assistance on case write-ups or other projects beyond what is au thorized by the assigning instructor. It is also cheating to accept the benefit( s) of another person s theft(s) even if not actively sought. For instance, if on e continues to be attentive to an overhead conversation about a test or case wri te-up even if initial exposure to such information was accidental and beyond the control of the student in question, one is also cheating. If a student overhear s a conversation or any information that any faculty member might reasonably wis h to withhold from the student, the student should inform the faculty member(s) of the information and circumstance under which it was overheard. Actions Required for Responding to Suspected and Known Violations As stated, everyone must abide by the Honor System and be intolerant of violatio ns. If you suspect a violation has occurred, you should first spea to the suspe cted violator in an attempt to determine if an infraction has ta en place. If, a fter doing so, you still believe that a violation has occurred, you must tell th e suspected violator that he or she must report himself or herself to the course professor or Associate Dean of the Graduate School of Business. If the individu al fails to report himself or herself within 48 hours, it then becomes your obli gation to report the infraction to the course professor or the Associate Dean of the Graduate School of Business. Remember that although you are not required by regulation to ta e any action, our Honor System is only as effective as you ma e it. If you remain silent when you suspect or now of a violation, you are appr oving of such dishonorable conduct as the community standard. You are thereby pr ecipitating a repetition of such violations. The Honor Pledge The University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business requires each enrol

led student to adopt the Honor System. The Honor Pledge best describes the condu ct promoted by the Honor System. It is as follows: "I affirm that I belong to the honorable community of The University of Texas at Austin Graduate School of Business. I will not lie, cheat or steal, nor will I tolerate those who do." "I pledge my full support to the Honor System. I agree to be bound at all times by the Honor System and understand that any violation may result in my dismissal from the Graduate School of Business." The following pages provide specific guidance about the Standard of Academic Int egrity at the University of Texas at Austin. Please read it carefully and feel f ree to as me any questions you might have. Excerpts from the University of Texas at Austin Office of the Dean of Students w ebsite (http://deanofstudents.utexas.edu/sjs/acint_student.php) The Standard of Academic Integrity A fundamental principle for any educational institution, academic integrity is h ighly valued and seriously regarded at The University of Texas at Austin, as emp hasized in the standards of conduct. More specifically, you and other students a re expected to "maintain absolute integrity and a high standard of individual ho nor in scholastic wor " underta en at the University (Sec. 11-801, Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities). This is a very basic expectation tha t is further reinforced by the University s Honor Code. At a minimum, you should complete any assignments, exams, and other scholastic endeavors with the utmost honesty, which requires you to: ac nowledge the contributions of other sources to your scholastic efforts; complete your assignments independently unless expressly authorized to see or o btain assistance in preparing them; follow instructions for assignments and exams, and observe the standards of your academic discipline; and avoid engaging in any form of academic dishonesty on behalf of yourself or anoth er student. For the official policies on academic integrity and scholastic dishonesty, pleas e refer to Chapter 11 of the Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activit ies. What is Scholastic Dishonesty? In promoting a high standard of academic integrity, the University broadly defin es scholastic dishonestybasically, all conduct that violates this standard, inclu ding any act designed to give an unfair or undeserved academic advantage, such a s: Cheating Plagiarism Unauthorized Collaboration Collusion Falsifying Academic Records Misrepresenting Facts (e.g., providing false information to postpone an exam, ob tain an extended deadline for an assignment, or even gain an unearned financial benefit) Any other acts (or attempted acts) that violate the basic standard of academic i ntegrity (e.g., multiple submissionssubmitting essentially the same written assig nment for two courses without authorization to do so) Several types of scholastic dishonestyunauthorized collaboration, plagiarism, and multiple submissionsare discussed in more detail on this Web site to correct com mon misperceptions about these particular offenses and suggest ways to avoid com mitting them. For the University s official definition of scholastic dishonesty, see Section 1 1-802, Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities. Unauthorized Collaboration If you wor with another person on an assignment for credit without the instruct or s permission to do so, you are engaging in unauthorized collaboration. This common form of academic dishonesty can occur with all types of scholastic w

or papers, homewor , tests (ta e-home or in-class), lab reports, computer program ming projects, or any other assignments to be submitted for credit. For the University s official definitions of unauthorized collaboration and the related offense of collusion, see Sections 11-802(c)(6) & 11-802(e), Institution al Rules on Student Services and Activities. Some students mista enly assume that they can wor together on an assignment as long as the instructor has not expressly prohibited collaborative efforts. Actually, students are expected to complete assignments independently unless the course instructor indicates otherwise. So wor ing together on assignments is no t permitted unless the instructor specifically approves of any such collaboratio n. Unfortunately, students who engage in unauthorized collaboration tend to justify doing so through various rationalizations. For example, some argue that they co ntributed to the wor , and others maintain that wor ing together on an assignmen t "helped them learn better." The instructornot the studentdetermines the purpose of a particular assignment and the acceptable method for completing it. Unless wor ing together on an assignme nt has been specifically authorized, always assume it is not allowed. Many educators do value group assignments and other collaborative efforts, recog nizing their potential for developing and enhancing specific learning s ills. An d course requirements in some classes do consist primarily of group assignments. But the expectation of individual wor is the prevailing norm in many classes, consistent with the presumption of original wor that remains a fundamental tene t of scholarship in the American educational system. Some students incorrectly assume that the degree of any permissible collaboratio n is basically the same for all classes. The extent of any permissible collaboration can vary widely from one class to th e next, even from one project to the next within the same class. Be sure to distinguish between collaboration that is authorized for a particular assignment and unauthorized collaboration that is underta en for the sa e of ex pedience or convenience to benefit you and/or another student. By failing to ma e this ey distinction, you are much more li ely to engage in unauthorized colla boration. To avoid any such outcome, always see clarification from the instruct or. Unauthorized collaboration can also occur in conjunction with group projects. How so? If the degree or type of collaboration exceeds the parameters expressly approved by the instructor. An instructor may allow (or even expect) students to wor together on one stage of a group project but require independent wor on o ther phases. Any such distinctions should be strictly observed. Providing another student unauthorized assistance on an assignment is also a vio lation, even without the prospect of benefiting yourself. If an instructor did not authorize students to wor together on a particular ass ignment and you help a student complete that assignment, you are providing unaut horized assistance and, in effect, facilitating an act of academic dishonesty. E qually important, you can be held accountable for doing so. For similar reasons, you should not allow another student access to your drafted or completed assignments unless the instructor has permitted those materials to be shared in that manner. Plagiarism Plagiarism is another serious violation of academic integrity. In simplest terms , this occurs if you represent as your own wor any material that was obtained f rom another source, regardless how or where you acquired it. Plagiarism can occur with all types of mediascholarly or non-academic, published or unpublishedwritten publications, Internet sources, oral presentations, illustr ations, computer code, scientific data or analyses, music, art, and other forms of expression. (See Section 11-802(d) of the Institutional Rules on Student Serv ices and Activities for the University s official definition of plagiarism.) Borrowed material from written wor s can include entire papers, one or more para graphs, single phrases, or any other excerpts from a variety of sources such as boo s, journal articles, magazines, downloaded Internet documents, purchased pap

ers from commercial writing services, papers obtained from other students (inclu ding homewor assignments), etc. As a general rule, the use of any borrowed material results in plagiarism if the original source is not properly ac nowledged. So you can be held accountable fo r plagiarizing material in either a final submission of an assignment or a draft that is being submitted to an instructor for review, comments, and/or approval. Using verbatim material (e.g., exact words) without proper attribution (or credi t) constitutes the most blatant form of plagiarism. However, other types of mate rial can be plagiarized as well, such as ideas drawn from an original source or even its structure (e.g., sentence construction or line of argument). Improper or insufficient paraphrasing often accounts for this type of plagiarism . (See additional information on paraphrasing.) Plagiarism can be committed intentionally or unintentionally. Strictly spea ing, any use of material from another source without proper attrib ution constitutes plagiarism, regardless why that occurred, and any such conduct violates accepted standards of academic integrity. Some students deliberately plagiarize, often rationalizing this misconduct with a variety of excuses: falling behind and succumbing to the pressures of meeting deadlines; feeling overwor ed and wishing to reduce their wor loads; compensatin g for actual (or perceived) academic or language deficiencies; and/or justifying plagiarism on other grounds. But some students commit plagiarism without intending to do so, often stumbling into negligent plagiarism as a result of sloppy noteta ing, insufficient paraphr asing, and/or ineffective proofreading. Those problems, however, neither justify nor excuse this breach of academic standards. By misunderstanding the meaning o f plagiarism and/or failing to cite sources accurately, you are much more li ely to commit this violation. Avoiding that outcome requires, at a minimum, a clear understanding of plagiarism and the appropriate techniques for scholarly attrib ution. (See related information on paraphrasing; noteta ing and proofreading; an d ac nowledging and citing sources.) By merely changing a few words or rearranging several words or sentences, you ar e not paraphrasing. Ma ing minor revisions to borrowed text amounts to plagiaris m. Even if properly cited, a "paraphrase" that is too similar to the original sourc e s wording and/or structure is, in fact, plagiarized. (See additional informati on on paraphrasing.) Remember, your instructors should be able to clearly identify which materials (e .g., words and ideas) are your own and which originated with other sources. That cannot be accomplished without proper attribution. You must give credit whe re it is due, ac nowledging the sources of any borrowed passages, ideas, or othe r types of materials, and enclosing any verbatim excerpts with quotation mar s ( using bloc indentation for longer passages). Plagiarism & Unauthorized Collaboration Plagiarism and unauthorized collaboration are often committed jointly. By submitting as your own wor any unattributed material that you obtained from other sources (including the contributions of another student who assisted you i n preparing a homewor assignment), you have committed plagiarism. And if the in structor did not authorize students to wor together on the assignment, you have also engaged in unauthorized collaboration. Both violations contribute to the s ame fundamental deceptionrepresenting material obtained from another source as yo ur own wor . Group efforts that extend beyond the limits approved by an instructor frequently involve plagiarism in addition to unauthorized collaboration. For example, an i nstructor may allow students to wor together while researching a subject, but r equire each student to write a separate report. If the students collaborate whil e writing their reports and then submit the products of those joint efforts as i ndividual wor s, they are guilty of unauthorized collaboration as well as plagia rism. In other words, the students collaborated on the written assignment withou t authorization to do so, and also failed to ac nowledge the other students con

tributions to their own individual reports. Multiple Submissions Submitting the same paper (or other type of assignment) for two courses without prior approval represents another form of academic dishonesty. You may not submit a substantially similar paper or project for credit in two (o r more) courses unless expressly authorized to do so by your instructor(s). (See Section 11-802(b) of the Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities for the University s official definition of scholastic dishonesty.) You may, however, re-wor or supplement previous wor on a topic with the instru ctor s approval. Some students mista enly assume that they are entitled to submit the same paper (or other assignment) for two (or more) classes simply because they authored the original wor . Unfortunately, students with this viewpoint tend to overloo the relevant ethica l and academic issues, focusing instead on their own "authorship" of the origina l material and personal interest in receiving essentially double credit for a si ngle effort. Unauthorized multiple submissions are inherently deceptive. After all, an instru ctor reasonably assumes that any completed assignments being submitted for credi t were actually prepared for that course. Mindful of that assumption, students w ho "recycle" their own papers from one course to another ma e an effort to conve y that impression. For instance, a student may revise the original title page or imply through some other means that he or she wrote the paper for that particul ar course, sometimes to the extent of discussing a "proposed" paper topic with t he instructor or presenting a "draft" of the paper before submitting the "recycl ed" wor for credit. The issue of plagiarism is also relevant. If, for example, you previously prepar ed a paper for one course and then submit it for credit in another course withou t citing the initial wor , you are committing plagiarismessentially "self-plagiar ism"the term used by some institutions. Recall the broad scope of plagiarism: all types of materials can be plagiarized, including unpublished wor s, even papers you previously wrote. Another problem concerns the resulting "unfair academic advantage" that is speci fically referenced in the University s definition of scholastic dishonesty. If y ou submit a paper for one course that you prepared and submitted for another cla ss, you are simply better situated to devote more time and energy toward fulfill ing other requirements for the subsequent course than would be available to clas smates who are completing all course requirements during that semester. In effec t, you would be gaining an unfair academic advantage, which constitutes academic dishonesty as it is defined on this campus. Some students, of course, do recognize one or more of these ethical issues, but still refrain from citing their authorship of prior papers to avoid earning redu ced (or zero) credit for the same wor s in other classes. That underlying motiva tion further illustrates the deceptive nature of unauthorized multiple submissio ns. An additional issue concerns the problematic minimal efforts involved in "recycl ing" papers (or other prepared assignments). Exerting minimal effort basically u ndercuts the curricular objectives associated with a particular assignment and t he course itself. Li ewise, the practice of "recycling" papers subverts importan t learning goals for individual degree programs and higher education in general, such as the mastery of specific s ills that students should acquire and develop in preparing written assignments. This demanding but necessary process is somew hat analogous to the required regimen of athletes, li e the numerous laps and ot her repetitive training exercises that runners must successfully complete to pre pare adequately for a marathon.

You might also like

- Personal Skills AuditDocument6 pagesPersonal Skills Auditcla22111No ratings yet

- Systematic Whs - Assessment 1Document9 pagesSystematic Whs - Assessment 1Nascimento YaraNo ratings yet

- Addressing Selection CriteriaDocument4 pagesAddressing Selection CriteriaKathy_Lu_9917No ratings yet

- Corporate Culture at FAW-VWDocument2 pagesCorporate Culture at FAW-VWUsman MahmoodNo ratings yet

- CLDM Project Guidelines at Version 5.2, February 2017Document22 pagesCLDM Project Guidelines at Version 5.2, February 2017GPNo ratings yet

- Professional Development Plan 2Document12 pagesProfessional Development Plan 2api-354412081No ratings yet

- Mentorship Program Outline For WebsiteDocument2 pagesMentorship Program Outline For Websiteapi-260036142No ratings yet

- Google PM 学习笔记C1-W1-W2Document3 pagesGoogle PM 学习笔记C1-W1-W2Yan Zhao100% (1)

- AudioDocument6 pagesAudioapi-319731120No ratings yet

- Assessments outcomes SAQADocument8 pagesAssessments outcomes SAQAtangwanlu9177No ratings yet

- Assessing Teaching and LearningDocument3 pagesAssessing Teaching and LearningWink YagamiNo ratings yet

- Assignment Brief For Unit 14 HND Health and Social Care by Shan WikoonDocument4 pagesAssignment Brief For Unit 14 HND Health and Social Care by Shan WikoonShan Wikoon LLB LLMNo ratings yet

- Career Development Competencies AssessmentDocument3 pagesCareer Development Competencies AssessmentAndreeaMare1984No ratings yet

- Ab Unit 22Document7 pagesAb Unit 22api-200177496No ratings yet

- Le18 Program GuideDocument17 pagesLe18 Program Guideektasharma123No ratings yet

- MGT 321 Courseoutline Summer15Document5 pagesMGT 321 Courseoutline Summer15souravsamNo ratings yet

- LMD Assignment Semester Two February 2015 Subject To External Examiner ApprovalDocument7 pagesLMD Assignment Semester Two February 2015 Subject To External Examiner ApprovalH'asham TariqNo ratings yet

- On-job training report for B.Com internshipDocument32 pagesOn-job training report for B.Com internshipNeha SinghNo ratings yet

- El 5623 Module 4Document6 pagesEl 5623 Module 4api-288414853100% (1)

- Developing A Course SyllabusDocument2 pagesDeveloping A Course SyllabusfidelbustamiNo ratings yet

- Assignment Learning Objectives: Career Exploration (Worth 20 Points) : Due Monday 12/3 by 8:00 AmDocument2 pagesAssignment Learning Objectives: Career Exploration (Worth 20 Points) : Due Monday 12/3 by 8:00 AmJo SeanNo ratings yet

- Competency Assessment Tier 1Document30 pagesCompetency Assessment Tier 1Nikki JohansenNo ratings yet

- Cur528 Assessing Student Learning Rachel FreelonDocument6 pagesCur528 Assessing Student Learning Rachel Freelonapi-291677201No ratings yet

- Professional Plan-Faculty TemplateDocument2 pagesProfessional Plan-Faculty Templatejaspar12No ratings yet

- Dett621 A3 and RubricDocument3 pagesDett621 A3 and Rubricapi-238107999No ratings yet

- Online Training DevelopmentDocument6 pagesOnline Training DevelopmentNandakumarNo ratings yet

- Probationary Reviews ProcessDocument4 pagesProbationary Reviews ProcessVin RamosNo ratings yet

- Business Signature AssignmentDocument11 pagesBusiness Signature Assignmentapi-315582766100% (1)

- Developing Courses in 9 PhasesDocument18 pagesDeveloping Courses in 9 PhasesNhial AbednegoNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For bps6310.502 06s Taught by Seunghyun Lee (sxl029100)Document15 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For bps6310.502 06s Taught by Seunghyun Lee (sxl029100)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Reflection in ActionDocument6 pagesReflection in ActionDarakhshan Fatima/TCHR/BKDCNo ratings yet

- Gems Global Leadership and Management Standards Evidence Sources Per StandardDocument17 pagesGems Global Leadership and Management Standards Evidence Sources Per Standardapi-268633795No ratings yet

- Rubric 3Document1 pageRubric 3api-338694667No ratings yet

- A Model of The Transfer ProcessDocument18 pagesA Model of The Transfer ProcessGullabudin Hassan ZadaNo ratings yet

- Unit 01Document17 pagesUnit 01Maniruzzaman Tanvir100% (7)

- My Interpersonal Communication PlanDocument3 pagesMy Interpersonal Communication PlanEsteban Wladimir Bastidas LeonNo ratings yet

- Professional Development PlanDocument4 pagesProfessional Development Planapi-283398555No ratings yet

- Assessment & Development Centre Workshop FactsheetDocument5 pagesAssessment & Development Centre Workshop FactsheetMegan RamsayNo ratings yet

- Depm 604-Major Paper-Final DraftDocument13 pagesDepm 604-Major Paper-Final Draftapi-237484773No ratings yet

- OUMH1103: Goals, Obstacles and Resources for Open and Distance LearningDocument12 pagesOUMH1103: Goals, Obstacles and Resources for Open and Distance LearningLany BalaNo ratings yet

- Mission Vision Values WorksheetDocument3 pagesMission Vision Values WorksheetAli SabalbalNo ratings yet

- College Success Workshop SurveyDocument1 pageCollege Success Workshop Surveyapi-237572085No ratings yet

- MKTG 323 - Channel Management - Muhammad Luqman AwanDocument6 pagesMKTG 323 - Channel Management - Muhammad Luqman AwanFaiza SaeedNo ratings yet

- GCE and Business Ethics Assignment - BUSN119 - S20Document3 pagesGCE and Business Ethics Assignment - BUSN119 - S20oiygbiuybiuNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning For LeadershipDocument12 pagesBlended Learning For LeadershipPenni OwenNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Influence of Training and Development On Organizational Performance at Pt. Bank Tabungan Negara (Persero) TBK ManadoDocument10 pagesAnalyzing The Influence of Training and Development On Organizational Performance at Pt. Bank Tabungan Negara (Persero) TBK ManadoChukriCharbetjiNo ratings yet

- MKTG 392-Brand Management-Sarah Suneel SarfrazDocument8 pagesMKTG 392-Brand Management-Sarah Suneel SarfrazAbdullahIsmailNo ratings yet

- L D Course Outline - IIM SambDocument5 pagesL D Course Outline - IIM SambnikhilaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of OD InterventionsDocument13 pagesAn Overview of OD InterventionsyogibmsNo ratings yet

- SPRING 2020 - Syllabus - BUS100-002 - Revised For Online VersionDocument13 pagesSPRING 2020 - Syllabus - BUS100-002 - Revised For Online VersionjoeNo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Training and DevelopmentDocument6 pagesCompetency-Based Training and Developmentmuna moonoNo ratings yet

- Competency AssessmentDocument6 pagesCompetency Assessmentapi-199567491No ratings yet

- Integrating Leadership Development and Succession Planning Best PracticesDocument25 pagesIntegrating Leadership Development and Succession Planning Best PracticestalalarayaratamaraNo ratings yet

- Learningreflections Danobrlen r1Document5 pagesLearningreflections Danobrlen r1api-324079029No ratings yet

- Vu Lesson Plan Template 2Document6 pagesVu Lesson Plan Template 2api-269547550No ratings yet

- Barriers To Strategic Planning PDFDocument4 pagesBarriers To Strategic Planning PDFsanjaycrNo ratings yet

- Personal Development PlanDocument3 pagesPersonal Development Planapi-661512870No ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Ob6301.502.08f Taught by Orlando Richard (Pretty)Document9 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Ob6301.502.08f Taught by Orlando Richard (Pretty)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Assignment 103.....Document20 pagesAssignment 103.....Devish WakdeNo ratings yet

- Classical Conditioning TheoryDocument2 pagesClassical Conditioning TheoryChell MariaNo ratings yet

- Montessori's Science of PeaceDocument3 pagesMontessori's Science of PeacekatyarafaelNo ratings yet

- The Interplay Between Technology and Humanity and Its Effect in The SocietyDocument53 pagesThe Interplay Between Technology and Humanity and Its Effect in The SocietyXander EspirituNo ratings yet

- 2016 Xu & Brown TALiP-TATE Author VersionDocument39 pages2016 Xu & Brown TALiP-TATE Author VersionRefi SativaNo ratings yet

- CPD4706 Assessment GuidanceDocument10 pagesCPD4706 Assessment GuidanceSnehanshNo ratings yet

- Episode 1 FS3Document48 pagesEpisode 1 FS3Jovielene Mae SobusaNo ratings yet

- College Preparedness Questionnaire 2 For ReferenceDocument16 pagesCollege Preparedness Questionnaire 2 For ReferenceGSTC DigosNo ratings yet

- The Automation Readiness Index 2018Document33 pagesThe Automation Readiness Index 2018reinarudoNo ratings yet

- BandedDocument4 pagesBandedyasie surbonaNo ratings yet

- ThaumatropeDocument17 pagesThaumatropeapi-372340240No ratings yet

- TranscriptDocument2 pagesTranscriptapi-379818799No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: A Friend Like You Grade: One: Friend Like You by Frank Murphy and Charnaie Gordon, and Illustrated byDocument5 pagesLesson Plan: A Friend Like You Grade: One: Friend Like You by Frank Murphy and Charnaie Gordon, and Illustrated byapi-573171836No ratings yet

- New TIP Course 4 (DepEd Teacher)Document67 pagesNew TIP Course 4 (DepEd Teacher)Eli Jad CapisondaNo ratings yet

- Rodolfo M. Evasco, JR.: Buhang NHS, Buhang, Bulusan, Sorsogon Secondary School Principal IIDocument55 pagesRodolfo M. Evasco, JR.: Buhang NHS, Buhang, Bulusan, Sorsogon Secondary School Principal IIAlex Sanchez100% (1)

- Economics of Social Sector and Environment Exam QuestionsDocument35 pagesEconomics of Social Sector and Environment Exam QuestionsnitikanehiNo ratings yet

- TAELLN411 Set 1 Written AssessmentDocument9 pagesTAELLN411 Set 1 Written Assessmentkiran seerooNo ratings yet

- Fifth Grade Incentives and RecognitionDocument2 pagesFifth Grade Incentives and Recognitionjsouther123No ratings yet

- Year 2000 AICTE Norms For Self Financed Colleges PDFDocument44 pagesYear 2000 AICTE Norms For Self Financed Colleges PDFPradiptapb100% (1)

- Pub-4-Byjus The Learning App An InvestigativeDocument7 pagesPub-4-Byjus The Learning App An InvestigativeAakash MauryNo ratings yet

- Flood Control 2015 Five Years of Innovat PDFDocument112 pagesFlood Control 2015 Five Years of Innovat PDFMugiwara SparrowNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PROPOSAL - FORMAT For Practical Research 2Document10 pagesRESEARCH PROPOSAL - FORMAT For Practical Research 2Tisha GaloloNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument10 pagesLesson PlanOliver IpoNo ratings yet

- Educ 7-SandiegoDocument6 pagesEduc 7-SandiegoCindy Malabanan SanDiego75% (4)

- Assessing Learning Outcomes Using Bloom's, Anderson's and McTighe's TaxonomiesDocument5 pagesAssessing Learning Outcomes Using Bloom's, Anderson's and McTighe's TaxonomiesElrose Saballero KimNo ratings yet

- Small TownDocument38 pagesSmall Townhepali6560No ratings yet

- ATTENDANCEDocument9 pagesATTENDANCEHaydeehh BaldinoNo ratings yet

- Nabil Anwar Academic CV Vitae 2014Document4 pagesNabil Anwar Academic CV Vitae 2014Gary TomNo ratings yet

- Barker - 2007 - The Leadership Paradox - Can Schools Leaders Transform Student OutcomesDocument24 pagesBarker - 2007 - The Leadership Paradox - Can Schools Leaders Transform Student OutcomesDágelaNo ratings yet

- Exploring Educational Theory 2012 - SCDDocument28 pagesExploring Educational Theory 2012 - SCDDavid JenningsNo ratings yet

- Cl.6 U.6L.5 Shopping at The GroceryDocument5 pagesCl.6 U.6L.5 Shopping at The GroceryAlina CebotariNo ratings yet