Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jeff Thompson Research Application

Uploaded by

rodickwh70800 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

181 views33 pagesEDUC 624

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEDUC 624

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

181 views33 pagesJeff Thompson Research Application

Uploaded by

rodickwh7080EDUC 624

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 33

Page 1

International Baccalaureate Organization 2011

Professor Jeff Thompson Research Award

Application Form

Name and school details

Surname:

Rodick

Given names:

William

School Name: Escola Americana de Belo

Horizonte

IB School code: 000123

School address:

Avenida Professor Mario Werneck, 3002 Bairro Buritis

Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil 30575-180

Country:

Brazil

Position in school:

Curriculum Coordinator

Tel: +55 31 3378-6700 Fax: +55 31 3378-6878

Email: william@eabh.com.br

rodickwh@gmail.com

Name of school head/principal/CEO:

Director Catarina Song Chen

Email of school head/principal/CEO:

director@eabh.com.br

Professional details

Teaching experience:

Escola Americana de Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2011-Current

Curriculum Coordinator, Dean of Students, AP English Teacher

IB MYP Year 5 Language A Teacher

Escola Americana de Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2009-2011

AP English Teacher, IB MYP Years 2-5 Language A Teacher

Singapore International School, India, 2008-2009

English Teacher for grades 3, 5, 7, and 8

Ivanna Eudora Kean High School, U.S. Virgin Islands, 2007-2008

English Teacher for grades 10 and 11, ESL Teacher, Writing Teacher

Leone High School, American Samoa, 2006-2007

English Teacher for grades 10 and 11

Qualifications:

Graduate Certificate in Advanced International Baccalaureate Studies, Fast Train

George Mason University 2011-2012

Page 2

M.Ed.: Curriculum and Instruction, Advanced Studies in Teaching and Learning

George Mason University 2011-2013

B.A.: English

James Madison University 2005

Previous research experience:

Some within graduate coursework

Previous research awards (if applicable):

None

Publications (if applicable):

None

Project details

Maximum of 800 words for this section

Title:

Mapping Curriculum for Alignment and Articulation

Objective(s):

To evaluate the influence of online curriculum mapping and planning software on the

alignment and articulation of school curriculum with IB MYP standards and practices, by

assessing influence upon

1. Collaborative planning

2. Coverage of the Areas of Interaction

3. Summative assessment

Proposed activity and research methodology-- include at minimum in the methodology

description your research question(s), methods of qualitative and or quantitative data

collection, and method of data analysis:

Research Questions:

How effectively do online curriculum planning tools promote alignment, articulation and

teacher collaboration in the IB Middle Years Programme?

1. In what ways does an electronic curriculum design interface influence collaborative

planning of teachers in an MYP World School?

2. In what ways can teachers use online curriculum design to ensure balanced coverage

of the MYP Areas of Interaction?

3. a. Does implementation of online curriculum mapping make teachers more attentive

to summative assessment? If so, how?

b. In what ways does online mapping influence cross-curricular assessment?

4. Does implementation of an electronic curriculum design interface lead to greater

practice and delivery of IB programmes? If so, in what ways?

Page 3

Data Collection

1. Teachers will be surveyed before implementation (Appendix A), at least four times

during the process of use, and once upon project completion. Data includes self-

evaluation of practices and whole school evaluation. Some question content is

repeated to check consistency.

2. At least one assessment example per subject area will be collected and evaluated

(once at the beginning of the project and once at the end) using a rubric that

examines the presence and effectiveness of cross-curricular elements and AOI

connections. Data will be cross-referenced against data collected through surveys.

Data Analysis

1. Data derived from Google Forms surveys will be compiled based on type and coded

to provide assertions about collaboration, AOIs, assessment, differentiation, and 21

st

century skill instruction. Progressive, comparative qualitative and quantitative data will

indicate the degree of influence of the online mapping software on these areas.

2. The investigator will analyse data entered and used in the electronic curriculum

design interface, which will provide comparative data to the survey results, indicating

collaboration occurrence, interdisciplinary teaching presence, AOI balance, and

assessment success. This document review will occur using the mapping softwares

live interface that collects unit plans and discovers connections between plans.

3. Informal classroom observations will provide information about consistency between

plan elements and classroom teaching, particularly in the areas of 21

st

century skills,

international mindedness, and IB standards and practices.

*Please note: Development of the survey, research questions, and rubric required insight from

proven experts in education (Appendix F).

Timeline:

The initial survey will take place before the electronic curriculum design interface is put into

use at the school, and data will be collected for two full semesters of use.

Expected outcomes including relevance to the IB and benefits to the school:

Based on initial research, it is expected that the live curriculum mapping software will prove to

serve as a platform for communication and collaboration. It is expected that the integration

and connections between unit plans created by using the software will improve balance and

depth of AOI instruction, improve our standing in self-assessment criteria related to IB

standards and practices, and enhance the sharing of best practices that will allow for

improved differentiation and effective, authentic, summative assessment.

This project is directly relevant to the IB as we will evaluate and explore opportunities for

improving the implementation of IB curriculum at our school. This project will assist in the

alignment and articulation of the IB MYP (and following this project, the investigator will

similarly explore integration of the IB PYP with this research along with our other programs of

continuum). This project and its outcomes are aimed at exploration of student development as

international-minded, 21

st

century, lifelong learners.

The created opportunities for practitioner reflection, dialogue, resources, and skill building will

compensate for the limited opportunities our schedule allows for sharing practices and

collaborating for interdisciplinary teaching. Therefore, this research will prove useful to many

private, international schools that are looking for similar solutions.

Page 4

Proposed dissemination of results:

EABH Community

1. Reports for future IB and AdvancED accreditation visits

2. Presentation to school board for action and budgeting of resources

3. Presentation to teachers to serve as a lead-in to IB self-review: We will use this data

to understand how to continuously improve our practice while compiling a wealth of

curriculum that is consistently reviewed.

IB

1. Paper to be submitted to IERD

2. Presentation to workshops and conferences if deemed admissible by IB

*Following the dissemination of publications, the investigator will look to continue such

research in our PYP program to lead to whole school continuum examination.

Further information

Co-investigators (if applicable):

None

Participating schools (if applicable):

None, as of yet

Evidence of investigator (or co-investigator) knowledge of applicable research

methodology:

The investigator will be pursuing this project as the curriculum coordinator of EABH and will

incorporate research methodology along with graduate coursework in Advanced International

Baccalaureate Studies at George Mason University.

Other support (if applicable, e.g. referees, endorsements, additional funding sources):

This research will center on the use of The Mondrian Wall as our curriculum mapping

software interface. This product is emerging for international use and utilizes real-time, live

functionality that increases efficiency and creates connections for teaching content across

curricula. As this software is in its early stages of use and without hard data or research, this

project will serve as fundamental in testing the possibilities for practitioner benefit of an

innovative direction for curriculum mapping design.

The investigator has discussed options with the school if he is granted partial funding from IB.

If he is granted partial funding, Escola Americana de Belo Horizonte is prepared to provide

additional funding.

A letter of support from the schools director is included as Appendix E.

Curriculum and Collaboration Survey

Planning

Planning

|| 1- None || 2- about 15 to 30 minutes || 3- about 30 to 45 minutes || 4- about 45 to 60 minutes || 5- 60 minutes or

more ||

None

about 15 to 30

minutes

about 30 to 45

minutes

about 45 to 60

minutes

60 minutes or

more

About how much time per

week do you spend

informally collaborating

with other teachers about

curriculum?

About how much time per

week do you spend formally

collaborating with other

teachers about curriculum?

Do you feel that you are able to give balanced coverage to the Areas of

Interaction? How or how are you not?

Please discuss specific coverage of each of the Areas of Interaction (Human Ingenuity, Environments, Health and Social

Education, Community and Service).

Which Area of Interaction do you feel is given the least attention or depth of

exploration in your teaching?

-------------------------------------

To what extent do you agree with these statements?

|| 1- Not at all || 2- To some degree || 3 || 4- Mostly || 5- Fully agree ||

Not at all

To some

degree

Mostly Fully agree

Collaborative planning and

reflection addresses the

requirements of the

programme(s).

Collaborative planning and

reflection takes place

regularly and

systematically.

Collaborative planning and

reflection addresses vertical

and horizontal articulation.

Collaborative planning and

reflection ensures that all

teachers have an overview

of students' learning

experiences.

Collaborative planning and

reflection is based on

agreed expectations for

student learning.

Collaborative planning and

reflection incorporates

differentiation for students'

learning needs and styles.

Collaborative planning and

reflection is informed by

assessment of student work

and learning.

Collaborative planning and

reflection recognizes that

all teachers are responsible

Appendix A Curriculum and Collaboration Survey

for language development

of students.

Collaborative planning and

reflection addresses the IB

learner profile attributes.

What makes collaboration difficult?

What might increase collaboration in our department?

Teaching

How effective is differentiation in your classroom?

Please check off the effective feedback checklist options listed here from Tomlinson and McTighe's Integrating

Differentiated Instruction and Understanding by Design, pages 44 to 57.

Get to know each student as a means of teaching him or her effectively.

Continually map the progress of students against essential outcomes.

Find alternate ways of teaching and alternate paths to learning to ensure continual growth of each student.

Provide support systems that persistently articulate to students and model for them what quality work looks like and

what it takes to attain quality results.

Elicit and value multiple perspectives on issues, decisions, and ways of accomplishing the work of the class.

Make sure all students[...] participate regularlywith no student or group of students either dominating the class or

receding from participation in it.

Design tasks that enable each student to make important contributions to the work of the group.

Make opportunities to communicate individually with individual learners.

Work to understand each students profile of academic strengths and weaknesses.

Observe students working individually, in small groups, and in the class as a whole with the intent to study factors

that facilitate or impede progress for individuals and for the group as a whole.

Create opportunities to learn from parents, guardians, and community members about students.

Explain the benefit in extending students strengths.

Help students acknowledge areas of weakness.

Facilitate ways to remediate or compensate for weaknesses.

Guide students in developing a vocabulary related to learning preferences and in exercising those preferences that

facilitate their growth.

Ask students to reflect on their own growth, factors that facilitate that growth, and likely next steps to ensure

continual growth.

Support students in setting and monitoring personal learning goals.

Allow for students different paces of learning.

Gather both basic and supplementary materials of different readability levels that reflect different cultures,

connect with varied interests, and are in different modes (e.g., auditory and visual).

Experiment with ways to rearrange furniture to allow for whole-class, small-group, and individual learning spaces.

Vary student groupings so that in addition to meeting readiness needs, they enable students to work with peers who

have similar and dissimilar interests, similar and dissimilar learning preferences, in random groups, in groups selected

by the teacher, and in those students select themselves.

Regularly teach to the whole class, to small groups based on assessed need, and to individuals.

Teach in a variety of ways to accommodate students varied readiness needs, interests, and learning preferences.

Ensure that grades communicate both personal growth and relative standing in regard to specified learning

outcomes.

Help students reflect on which strategies work well for them, why that might be the case, and what that reveals to

the student about him- or herself as a learner.

Engage students in setting personal goals and evaluating progress toward those goals.

Reflect consistently on individual and group growth in order to adjust instruction in ways of greatest benefit to

individuals and the class as a whole.

Appendix A Curriculum and Collaboration Survey

individuals and the class as a whole.

Please use this box to add any other information you feel may be important

about your responses to the last question, "How effective is differentiation in

your classroom?"

To what extent do you agree with these statements?

|| 1- Not at all || 2- To some degree || 3 || 4- Mostly || 5- Fully agree ||

Not at all

To some

degree

Mostly Fully agree

The content of my

instruction makes students

aware of international

issues.

My students learn how to

learn.

My students frequently solve

problems.

My students design

problems to solve

themselves.

My students communicate

and collaborate to solve

problems.

My learning environment

fosters questioning,

patience, openness to fresh

ideas, high levels of trust,

and learning from mistakes

and failures.

My students invent solutions

to real-world problems.

Please use this box to add any other information you feel may be important

about your responses to the last question.

Assessment

Assessment

|| 1- 0% || 2- about 10% || 3- about 25-40% || 4- about 50-70% || 5- 75% or more ||

0% about 10% about 25-40% about 50-70% 75% or more

What percentage of your

summative assessments

relate to subject area

objectives?

What percentage of your

summative assessments

relate to subject area

standards?

What percentage of your

summative assessments

provide information that is

used in cross-curricular

discussions with peers?

What percentage of your

summative assessments

cover standards from other

subject areas?

What percentage of your

summative assessments

cover objectives from other

subject areas?

Appendix A Curriculum and Collaboration Survey

subject areas?

What percentage of your

summative assessments are

interdisciplinary with one

other teacher?

What percentage of your

summative assessments are

interdisciplinary with two

other teachers?

What percentage of your

summative assessments are

interdisciplinary with three

or more other teachers?

How effective are your summative assessments?

Please check off the effective feedback checklist options listed here from Grant Wiggins's Educative Assessment, pages

22 and 49.

Provides confirming (or disconfirming) useful evidence of effect relative to intent, for example, a map and road

signs; compares work to anchor papers and rubrics.

Compares current performance and trend to successful result (standard), for example, the taste and appearance of

the food, not the recipe, guarantee the meal will come out as described; student work is compared against exemplars

and criteria.

Timely: immediate or performerfriendly in its immediacy, such as feedback from audience and conductor during a

recital.

Frequent and ongoing.

Descriptive language predominates in assessing aspects of performance, for example, you made a left turn onto

Main St. instead of a right turn; rubrics describe qualities of performance using concrete indicators and traits unique to

each level.

Performer perceives a specific, tangible effect, later symbolized by a score that the performer sees is an apt

reflection of the effect, such as the score given by a band judge in competition, based on specific criteria; the grade or

score confirms what was apparent to the performer about the quality of the performance after it happened.

The result sought is derived from true models (exemplars), for example, a first grade evaluation of reading is

linked to the capacities of a successful adult reader: the reading rubric is longitudinal and anchored by expert reading

behaviors; feedback is given in terms of the goal, such as the specific accomplishments of those who effectively read to

learn.

Enables performers to improve through self assessment and selfadjustment.

Is realistic. The task or tasks replicate the ways in which a person's knowledge and abilities are "tested" in real-

world situations.

Requires judgment and innovation. The student has to use knowledge and skills wisely and effectively to solve unstructured problems, such as when a plan must

be designed, and the solution involves more than following a set routine or procedure or plugging in knowledge.

Asks the student to "do" the subject. Instead of reciting, restating, or replicating through demonstration what he or she was taught or what is already known, the

student has to carry out exploration and work within the discipline of science, history, or any other subject.

Replicates or simulates the contexts in which adults are "tested" in the workplace, in civic life, and in personal life. Contexts involve specific situations that

have particular constraints, purposes, and audiences. Typical school tests are context-

less. Students need to experience what it is like to do tasks in workplace and other real-

life contexts, which tend to be messy and murky. In other words, genuine tasks require good judgment. Authentic tasks undo the ultimately harmful secrecy,-

silence, and absence of resources and feedback that mark excessive school testing.

Assesses the student's ability to efficiently and effectively use a repertoire of knowledge and skill to negotiate a complex task. Most conventional test items

are isolated elements of performance

similar to sideline drills in athletics rather than to the integrated use of skills that a game requires. Good judgment is required

here, too. Although there is, of course, a place for drill tests, performance is always more than the sum of the drills.

Allows appropriate opportunities to rehearse, practice, consult resources, and get feedback on and refine performances and products. Although there is a

role for the conventional "secure" test that keeps questions secret and keeps resource materials from students until during the test, that testing must coexist with

educative assessment if students are to improve performance! if we are to focus their learning, through cycles of performance

feedbackrevisionperformance, on the production of known high-

quality products and standards! and if we are to help them learn to use information, resources, and notes to effectively perform in -

context.

Please use this box to add any other information you feel may be important

about your responses to the last question, "How effective are your summative

assessments?"

Submit

Powered by Google Docs

Report Abuse - Terms of Service - Additional Terms

Appendix A Curriculum and Collaboration Survey

Appendix B Assessment Rubric and Differentiation Questionnaire

Criterion A: Cross-Curricular Elements

Maximum: 8

Achievement

Level

Level Descriptor Teacher Comments

0 The assessment piece does not reach a standard described by

any of the descriptors below.

1-2 The assessment piece meets only one or two of the following

criteria:

* allows students to use skills learned in more than one subject

area.

* allows some topical understanding of study in more than one

subject area.

* references either intercultural awareness or a real-world

connection to some degree by the student.

3-4 The assessment piece allows students to use skills learned in

more than one subject area.

The assessment piece allows some topical understanding of

study in more than one subject area.

The assessment piece references either intercultural awareness

or a real-world connection to some degree by the student.

5-6 The assessment piece requires student demonstration of

knowledge that integrates at least one objective from each of

more than one subject area.

The assessment piece demonstrates topical understanding of

study in more than one subject area.

The assessment piece requires a reference to intercultural

awareness by the student.

7-8 The assessment piece requires student demonstration of

knowledge that integrates several objectives from more than one

subject area.

The assessment piece demonstrates contextual understanding of

topics studied in more than one subject area.

The assessment piece requires a demonstration of intercultural

awareness by the student.

The assessment piece expects the student to apply knowledge

and skills innovatively to solve an unstructured problem,

replicating real-world experience.

Appendix B Assessment Rubric and Differentiation Questionnaire

Criterion B: Area of Interaction Depth

Maximum: 8

Achievement

Level

Level Descriptor Teacher Comments

0 The assessment piece does not reach a standard described by

any of the descriptors below.

1-2 The assessment pieces connection to the AOI seems contrived

and artificial.

The assessment piece limits active involvement and engagement

as the result of a faulty or absent linkage to the AOI.

The assessment piece is missing conceptual understanding and a

connection to a global issue context that could be expected from

depth of AOI study.

3-4 The assessment pieces connection to the AOI may be related,

but integration would possibly seem forced and unnatural.

The assessment piece promotes some involvement and

engagement that is somehow connected to the AOI.

The assessment piece allows for some conceptual exploration of

an issue, although perhaps only in part, through AOI reference.

5-6 The assessment pieces connection to the AOI seems related, but

could be integrated more fully.

The assessment piece promotes some active involvement and

engagement as a direct result of a logical linkage to the AOI.

The assessment piece expects conceptual understanding and

students explore the context of a global issue, although perhaps

only in part, through related AOI study.

7-8 The assessment pieces connection to the AOI reflects fluid

integration.

The assessment piece demands active involvement and

engagement as a direct result of valuable linkage to the AOI.

The assessment piece is rich in conceptual understanding and

students explore the context of a global issue as a result of AOI

study.

Appendix B Assessment Rubric and Differentiation Questionnaire

Differentiation Questionnaire

Question Response

1 Did this learning experience enable these

particular students to learn this material well?

2 Whose needs were not met with these learning

experiences?

3 Is there any portion of the expected

understandings that the lessons did not address?

4 Were the lessons that guided this assessment

necessary for all students?

5 How does this assessment meet the needs of

students who already understood this material

or who learned very quickly?

6 Does this assessment let me know that students

have mastered this material?

7 How had I taken the instructional pulse of the

students via formative assessments regarding

this material? Did formative assessment

influence instructional decisions that made this

summative assessment appropriate?

8 Did this unit go the way I wanted it to go? If

not, what got me off track?

Currl'cuum Mapppnge

lOiuildinag Aollaboraio and Gomunieaion

ANGELA KOPPANG

This article explores the application and use of curriculum map-

ping as a tool to assist teachers in communicating the content,

skills, and assessments used in their classrooms. The process of

curriculum mapping is explained, and the adaptation of the

process for special education teachers is detailed. Finally, ex-

amples are given of how curriculum mapping can assist both

special and general education teachers in meeting the needs of

students in the classroom. Although this article will apply the

use of curriculum mapping data at the middle school level, the

process of mapping is equally effective at the elementary and

high school levels.

VOL 39, NO. 3, JANUARY 2024 (P. 154-161)

154 IUMVElfflOll IN SCHOOL AND CUIIIC

Appendix C Research Text 1

rs. Anderson, a seventh-grade life science

teacher, has 24 students in her class, 4 of

whom are students with disabilities. Jesse

has a mild learning disability and needs

little assistance in the class, although he has

some difficulties with organization. Jenny and Brian have

mild cognitive disabilities and have some modified expec-

tations for vocabulary and lengthier written assign-

ments. John has multiple disabilities, including moderate

cogrutive impairment and physical disabilities. He is re-

sponsible only for a small part of the vocabulary and con-

tent, and his work is primarily designed to parallel the

classroom content In addition to these students, Mrs.

Anderson has Marina, an English language learner, and 19

other students of differing abilities. Twice each week, Mr.

Jones, a special education teacher, joins Mrs. Anderson,

and they share teaching responsibilities and group stu-

dents for instruction in a variety of ways. On the remain-

ing days, Mrs. Smith, a teaching assistant, is available to

assistMrs. Anderson and individual students in the class-

room. How do these teachers effectively communicate

about the content and skills that will be used in the class-

room? They base all instructional planning-as well as

decisions about curriculum adaptations and modifica-

tions-on the content, skills, and assessments found in

curriculum maps developed by the teachers in the school.

What Is Ourricului Mappiilg?

Curriculum mapping is a method of collecting data

about what is really being taught in schools. It has been

advocated as a method of aligning the written and taught

curriculum since the early 1970s. More recent advances

in technology have expanded the use of curriculum map-

ping as a tool for improving communication among

teachers about the content, skills, and assessments that

are a part of the instructional process. This new applica-

tion of curriculum mapping holds great promise for en-

hancing the collaboration between general and special

education teachers to benefit all learners.

Curriculum mapping is a process used to gather a

database of the operational curriculum of a school (Hayes-

Jacobs, 1997). Although most schools have well-developed

curriculum guides, information is often limited about how

the standards set forth in those guides directly relate to

what is actually happening in the classroom. Most cur-

riculum guides identify what students should know and

be able to do but give little insight into how students ac-

complish this learning or what assessment methods are

used by teachers. In combination with traditional curricu-

lum guides, curriculum maps can provide information

about content and skills used for instruction, as well as

the length of time devoted to various aspects of the cur-

riculum. Including assessment methods on the maps pro-

vides a link to the expectations for the manner in which

students will be expected to demonstrate their knowl-

edge. The details included in the curriculum maps give a

clearer picture of what actually occurs in each classroom.

In the curriculum mapping process, teachers use a

calendar-based system (see Table 1) to map the skills, con-

tent, and assessments used in their classrooms (Hayes-

Jacobs, 1997). Because each teacher takes an individual

approach to meeting the curriculum standards, the indi-

vidual maps will reflect the differences in approaches for

achieving curricular goals. The completed maps may be

used for many purposes, including

o aligning instruction to the written standards;

o developing integrated curriculum units;

o providing a baseline for the curriculum review and

renewal process;

* identifying staff development needs; and

* most important, providing communication among

teachers.

One of the most powerful outcomes of the curricu-

lum mapping process is using the maps as a conimunica-

tion tool among teachers -within a school.

Hayes-Jacobs (1997) said, "Curriculum mapping am-

plifies the possibilities for long-range planning, short-

term preparation, and clear communication" (p. 5). This

Table 1. Life Science Curriculum Map

Life science Content Skills Assessment

January . Characteristics of plants * List characteristics of plants * Plant worksheet

* Seedless plants * Compare vascular & nonvascular plants * Vascular plant art

o Seed plants * Describe & illustrate structures of roots, * Plant drawings

* Complex plants leaves, & stems * Oral presentation of group

* Plant reproduction * List characteristics of seed plants & find work in plant lab

* Rain forest seeds in plant lab * Flower lab report & labels

* Describe & label the functions of the * Rain forest essay

flower in flower dissection lab

* Describe methods of seed dispersal

* Understand the environmental impact of the rain

forest

VOL 39, NO. 3. JANUARY 2004 155

Appendix C Research Text 1

focus on planning, preparation, and communication facili-

tates a higher level of collaboration between general ed-

ucation teachers and special education staff. This process

can involve general and special educators on many differ-

ent levels to enhance effective collaboration within a

school.

Curriculum Mapping Process

While mapping is most effective when the entire school

staff is involved, many school staff members have started

this process by mapping one or two grade levels at an el-

ementary school or one interdisciplinary team or depart-

ment in middle or secondary schools. The process is

easily accomplished by both novice and veteran teachers.

The key to the success of the process is staff discussions

and how data are used after the maps are completed.

Each teacher begins the process of mapping by record-

ing his or her content, skills, and assessments. Using a

computer program enhances the process of mapping by

allowing for revision of the maps, as well as the ability to

share the maps throughout a school by posting them on

a server or school Web site. Several excellent software

programs are specifically designed for curriculum map-

ping; however, it is not necessary to purchase soffivare to

complete the mapping process. Many schools have

started the process with a simple computer template cre-

ated in a word-processing program resembling the one

found in Table 1. This enables teachers to benefit from

the use of technology in the mapping process, even if

they do not have access to curriculum mapping software.

Mapping Content, Skills, and Assessment

Teachers begin by recording the content for the course

or subject area. A curriculum map does not represent a

daily lesson plan but reflects the major concepts and con-

tent that will be covered during that period. In facilitat-

ing the process with teachers in a variety of settings, I

have found that on average, a teacher can map the con-

tent for one course or subject for the entire school year

in 30 to 45 minutes.

After completing the content, the teacher identifies

the key skills that will be used. The list of skills is often

significantly longer than the list of content, and as a re-

sult, the skills portion of the map takes the greatest

amount of time for teachers. I have found that it takes

most teachers 1 to 1N hours to complete the skills portion

of the map for one course or subject area for the school

year.

It is critical to identify the new skills that will be used

and to be specific enough in that description and identi-

fication that it is clear to other readers. For example, in-

stead of indicating that the students will be identifying

the animals found in the rain forest, you would indicate

that they would classify the animals by kingdom, phylum,

and genus. When mapping skills, it is important to iden-

tify the new skill or the new context in which the skill will

be applied. The more clearly the skill is identified, the

more useful the map will be to other teachers. Clarity re-

garding skills will enable special education teachers to

prepare a learner for the skills that will be used and help

the learner compensate for deficits in the skills so he or

she can fully participate in the classroom.

The final element of the curriculum map is assess-

ment-both formal and informal. Assessment strategies

should be identified for all content and skills on the

map. These could include informal assessments, such as

teacher observation and student self-assessments, as well

as formal assessments, such as student projects, presen-

tations, quizzes, and traditional tests. The process of

mapping assessments takes about 30 to 45 minutes to

complete for one course or subject area for the year.

Mapping Time Frame

Mapping one course or subject area for the year will take

about 2 to 3 hours and can be accomplished in several

ways. Mapping can be completed in advance of teaching

by projecting ahead for a month, a semester, or a entire

year. Mapping can be done at the completion of a school

156 lITERVElTIOU III SCHOOL AtD CLIUIC

Appendix C Research Text 1

year in preparation for the next year, or it can be com-

pleted month-by-month as you progress through the

school year. Many teachers find it easiest to map as they

go through the course of the school year and generally

find that it takes only about 15 to 20 minutes a month to

complete the map in this manner. Using a software pro-

gram or computer template for mapping allows teachers

to refine and realign their maps in an ongoing process

and facilitates sharing the maps with other teachers in the

building.

After all teachers complete their maps, copies of all

the maps are given to all teachers in the building. Every-

one reads the maps to gain an understanding of the con-

tent, skills, and assessments that will be covered in each

grade level or course. Sharing maps allows teachers to

gain information and identify repetitions, gaps, and po-

tential areas for integration. Teachers then come to-

gether in mixed groups to discuss the maps and compare

their findings. They determine any immediate revision

points and identify any areas that require research and

planning. Subcommittees are then formed to research

these issues and make recommendations to the staff re-

garding curriculum alignment. The powerful impact of

this process is that it puts decisions about curriculum

alignment in the hands of the teachers who deliver.thC

instruction.

Increased collaboration and communication among

teachers ultimately benefits the students. As the curricu-

lum alignment is achieved, students' educational experi-

ences are enhanced. The curriculum is more coherent

and clear for building knowledge and skills. In addition,

instruction becomes more closely aligned to the state find

district standards on which students will be tested. Fi-

nally, as teachers share infornation about what they teach,

they begin to dialogue and share effective instructional

strategies. General and special education teachers learn

from each other and build strong partnerships that pro-

vide instruction to best meet the needs of their students.

currioulum Mapping

for Special rducaiiov Teachers

Special education teachers use curriculum maps to get a

clear picture of the content, skills, and assessments used

in the general education classroom so they can assist stu-

dents with disabilities in inclusive classroom settings.

The information the map provides is critical in helping

special education teachers understand the instructional

processes students will experience in the general educa-

tion classroom. For those students with more severe dis-

abilities, instruction is often so highly individualized

that maps would have to be specific for each student to

give a clear picture of the instruction. To truly communi-

cate the appropriate information, traditional maps as com-

pleted by general education teachers would need to be

created for each individual student. Because this is al-

ready done as a part of Individualized Education Programs

(IEPs) the process would only increase the paperwork

load for special education teachers. A different process

must be used to develop communication among special

education staff members.

In working in schools with special education teachers

involved in curriculum mapping, I adapted a process that

has been used by library media specialists for special ed-

ucation staff. The special education staff began to com-

pile a list of curriculum-based resources that supported

the content, skills, and assessments outlined in general

education teachers' curriculum maps. These resources

were entered into a searchable database that was accessi-

ble by all staff in the building (see Table 2). The database

included information about the content and skills con-

tained in the materials, along with information such as an

approximation of reading level and/or the grade-level

equivalency of the materials. It included any other spe-

cialized adaptive information that would assist anyone

searching the database in understanding how the mater-

ial might support classroom instruction. The database in-

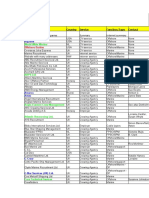

Table 2. Teacher Curriculum Resource List

Materials Publisher Features Map correlation Location

Trees and Plants in Steck Vaughn Reading Level 3 7th January Mental retardation

the Rain Forest Includes photos, stories, & Life Science classroom

activities about conservation

and environment

Flower parts Teacher made Includes digital photos of 7th January English as a second

parts of flowers with terms- Life Science language classroom

can be matched to actual

flower dissection

Johnny Tremain Recorded books Tape recording of full book 7th February Learning disabilities

text Language Arts classroom

The Call of the Wild Steck Vaughn Reading Level 4 8th December Library

Language Arts

VOL. 39. NJO. 3, JAIIUARY 2004 157

Appendix C Research Text 1

dicated where in the building these materials were lo-

cated and the contact staff person in charge of these ma-

terials.

Thus began a process of sharing curriculum materials

and other supportive resources among special education

staff members, as well as between special and general ed-

ucation teachers. Any staff member can access these ma-

terials to support the learning needs of students who are

not identified for any type of special service programs,

but who may have specialized learning needs. Curricu-

lum materials that parallel the classroom content to a

lower grade-level equivalency reading level could be used

to support English language learners (ELL) or students

with other learning delays. Teachers searching for mate-

rials to assist students in their classrooms can determine

if materials that may fit their purposes are available. In

addition, they know whom to contact about these mate-

rials. This often began a dialogue about strategies and

materials that support learning needs of students and cre-

ated a situation in which the special education teachers

were able to share their specialized skills in teaching strate-

gies with general education teachers. As teachers borrow

and adapt these materials for students in the classroom,

they gain more knowledge and skills in working with spe-

cialized learning needs of students with disabilities. They

are better prepared to serve not only students with dis-

abilities in their classrooms but all students in their class-

rooms.

After general education teachers complete their maps,

special education staff code the resource database to the

classroom teachers' maps, indicating those resources that

specifically support the content, skills, and assessments

used by the general education teachers. Not only does

this facilitate the sharing of resources, it also clearly iden-

tifies those areas in which the school does not currently

have many resources to support the classroom curricu-

lum. Available budget moneys can then be directed to-

ward the purchase or development of materials in those

areas. Rather than having each special education staff

member create his or her own adapted materials, educa-

tors can pool resources and expertise to find or develop

appropriate materials.

Sharing this information helps all educators better di-

rect limited budget resources and gives educators time to

acquire and develop materials that best support the actual

general education classroom curriculum and curriculum

standards. Sharing is facilitated not only between general

education teachers and special education teachers but

also among program areas within and outside of special

education.

Deviefits of OurriculuiAMv1appivig

Although curriculum maps facilitate communication

among teachers, the key benefit is improving the learn-

ing needs of all students, especially individuals with dis-

abilities. Special education teachers are able to develop a

clearer understanding of the general education classroom

curriculum, along with knowledge of the skills and as-

sessments that will be used. This information is vital for

general and special education teachers who collaborate to

support learning in the general education classroom. The

maps also provide a strong basis for making decisions

about inclusion and acquiring knowledge about the nec-

essary level of classroom adaptation and modification to

assist students with disabilites to participate in the gen-

eral education classroom and curriculum. Beneficial in-

formation gained from mapping includes preteaching

skills, correlating community-based outings with upcom-

ing curriculum-based content, and using alternative as-

sessments.

Maps give more detail about the skills and processes

that will be used in the general education classroom than

do traditional content-based lesson plans. Knowing the

skills that will be used in upcoming lessons, special edu-

cation teachers can begin to preteach skills to students

before the skills are introduced in the general education

classroom. This gives students more time and repetition

to learn skills. When the skill is introduced in the general

education classroom, these students will be able to par-

ticipate at a level more comparable to their peers and will

gain confidence in the ability to more fully participate in

the general classroom.

Students in Mrs. Anderson's science class will be work-

ing on a rain forest project that will culminate in an essay

about the rain forest. Mr. Jones, the special education

teacher, works with Mrs. Anderson's curriculum map to

identify the key concepts of the lesson. He prepares a

graphic organizer or concept map for the students to use

in class. This concept map is organized in a manner that

reflects the structure and relationship of the concepts that

will be highlighted in Mrs. Anderson's instruction about

the rain forest. This is a type of content-enhancement rou-

tine that improves the organization of the instruction by

presenting it in a learner-friendly format that emphasizes

the "big picture" ideas (Boudah, Lenz, Bulgren, Schu-

maker, & Deshler, 2000).

Mrs. Anderson and Mr. Jones model using the con-

cept map for organizing instruction while students take

notes or create their own concept maps. Students with

disabilities receive a partially completed concept map

that contains the key ideas and issues from the instruc-

tion (see Figure 1). The students add details to the con-

cept map in each of the identified key categories during

the instruction. Mr. Jones and Mrs. Anderson model how

to appropriately use the concept map by adding informa-

tion to a template of the map on an overhead project.

Having students fill in the information on this concept

map not only helps them stay organized but provides

them the multisensory approach of seeing the key con-

cepts on the graphic organizer, hearing concepts from the

158 IIIIERVYEDIOII IN SCHOOL AID CUnIIC

Appendix C Research Text 1

Figure 1. Rain forest concept map.

teacher, and writing concepts on the map. All of this

helps them retain information while focusing on the

most important concepts (Friend & Bursuck, 2001).

At the end of the lesson, students review the concepts

on the map and prepare questions for review, which they

can then use in class or at home to review and prepare for

a test. Students can use another template of the map as an

organizer to outline the key ideas from their reading as-

signment. Finally, concept maps can become the frame-

work for the information students will use to write their

essays on the rain forest.

To assist students in writing these essays, Mr. Jones

proposes to Mrs. Anderson that he teach a composition

strategy called DEFENDS (Ellis & Lenz, 1987) to the

science class. Mrs. Anderson is not familiar with this

strategy but recognizes that the DEFENDS strategy will

assist students as they write a paper defending their posi-

tion on the destruction of the rain forest (see Figure 1).

The strategy uses the following steps:

D Decide on an exact position

E Examine the reasons for the positions

F Form a list of points that explain each reason

E Expose the position in the first sentence

N Note each reason and supporting points

D Drive home the point in the last sentence

S Search for errors and correct

After Mr. Jones teaches the strategy to the class, he

works with a small group of students who need additional

assistance in the use of the strategy. When students have

completed their essays, all students are asked to use the

steps of the strategy to self-assess and refine them.

Curriculum maps also give special education teachers

more time to develop appropriate classroom activities

that parallel the classroom content for those students

who may need significant modifications to participate in

the general education classroom. Knowledge of the con-

tent, skills, and assessments used in the classroom will

help special education teachers identify activities that will

parallel general education activities and reinforce the

same skills at a different level. Teachers can analyze the

skills involved and determine if the student can perform

the same task as other students, perform the same task

with an easier step, perform the same task with different

materials, or perform a different task with the same theme

(Lowell-York, Doyle, & Kronberg, 1995).

In Mrs. Anderson's science class, students are classify-

ing types of animals by kingdom, phylum, and genus. A

student who is able to do the same task with an easier step

may be classifying an animal only by kingdom. A student

who needs to undertake the same task with different

materials may be using picture cards with the name and

pictures of animals. A student who needs to tackle a dif-

ferent task with the same theme may be naming animals

or detertnining if they live on land or water.

Knowledge of the content, skills, and assessments that

are part of the general education curriculum assists special

education teachers in planning community-based learn-

ing experiences that support the content being taught in

inclusive settings. Using the community-based experiences

to support inclusive classroom learning can also provide

VOL. 39, NO. 3. JAIIUARY 2094 159

Appendix C Research Text 1

Table 3. DEFENDS Strategy

D Decide on an exact position

E Examine the reasons for the positions

F Form a list of points that explain each reason

E Expose the position in the first sentence

N Note each reason & supporting points

D Drive home the point in the last sentence

s Search for errors and correct

opportunities for special education students to share what

they have gained with the general education students. If

the science class is studying reptiles, a community-based

learning experience might include a trip to a local pet

store or zoo. Students may take along an instant picture

or digital camera to record the reptiles they see on the

outing, or they may gather information about the reptiles

to share with their classmates when they return to school.

The photos and information gathered can become a part

of the curriculum materials for the special education stu-

dents as well as supporting materials for the general edu-

cation teachers and students.

One particularly successful community-based outing

involved having students purchase and prepare lab kits

for use in the science classroom. The science teacher pre-

pared a list of materials needed for an upcoming lab in

which students would dissect and label parts of a flower.

On a community-based outing, students purchased the

materials for the lab activity. They also visited a green-

house to learn about plants and to purchase the flowers

to be used in the lab. Students then worked with a teach-

ing assistant to learn how to assemble the materials into

lab kits to be used in the science lab. This collaboration

supported the learning needs of the special education stu-

dents and assisted the general education teacher in pre-

paring lab materials. The greatest benefit was the pride

students had later that day when they participated in the

lab activity that they had prepared. The science teacher

recognized their efforts, and they were able to share ma-

terials and photos they had gathered in their trip to the

greenhouse for the benefit of all students.

Finally, assessment information included on the cur-

riculum maps will help special education teachers under-

stand how general education teachers will be assessing

students' accomplishment in terms of the knowledge,

skills, and processes in the curriculum. Special education

teachers can assist students in developing study guides

and equip students with test-taking strategies that fit the

assessments used by general education teachers.

The student decides on his or her personal position about the

destruction of the rain forest

The student determines & explains why he or she holds these

beliefs

The student makes a list of points about the rain forest that

supports his or her beliefs

The student composes a topic sentence that supports his or

her position

The student creates short paragraphs that elaborate on the

points identified earlier

The student restates his or her position & reasons in the

summary statement

The student self-edits the essay

Special education teachers can use samples of class-

room projects and assessments to build a portfolio that

will demonstrate the attainment of EEP goals. In addi-

tion, information on the curriculum map offers general

and special educators the opportunity to collaborate on

alternative methods of assessing student knowledge. Be-

cause of the needs of their students, many special educa-

tion teachers have a great deal to offer general education

teachers in the development of assessment methods that

do not rely solely on traditional tests and quizzes. As gen-

eral education teachers collaborate on designing these al-

ternate assessments, they improve their own skills in

using multiple assessment methods.

1 BO IIITERVEIITID III SCHOOL AND CIDIIC

Appendix C Research Text 1

The greatest benefit of using curriculum maps is the

improved communication among all teachers in the school.

As special and general education teachers have a better

level of understanding of the content, skills, and assess-

ments used in classrooms, they can build stronger collab-

orations to assist all students with special learning needs.

General education teachers can gain a wealth of knowl-

edge about strategies and structures that support learning

from special education teachers. Special education teach-

ers benefit from curriculum mapping by gaining a deeper

understanding of the general classroom curriculum and

how they can create meaningful curricular connections

for students. Improved communication among all teach-

ers in the school provides professional educators with an-

other tool for effectively enhancing the learning of all

students in the classroom, especially students with dis-

abilities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Angela Koppang, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Educa-

tional Leadership Department at the University of North Da-

kota and specializes in the areas of curriculum, instruction, as-

sessment, and school leadership. She is a former elementary and

middle school teacher and administrator and serves as a consul-

tant in the areas of curriculum development and alignment.

Address: Angela Koppang, Department of Educational Leader-

ship, Box 7189, Grand Forks, ND 58201; e-mail: angela_

koppang@und.nodak.edu

REFERENCES

Boudah, D. J., Lenz, B. K, Bulgren,J. A., Schumaker,J. B., & Deshler,

D. D. (2000). Don't water down! Enhance content learning through

the unit organizer routine. Teacbing Exceptional Cbildren, 32(3), 48-56.

Ellis, E., & Lenz, K (1987). A component analysis of effective learning

strategies for LD students. Learning Disabilities Focus, 2, 94-107.

Friend, M., & Bursuck, W. D. (2001). Including students witb special

needs: A practical guide for classroom teachers (3rd ed.). Needham

Heights, MA. Allyn & Bacon.

Hayes-Jacobs, H. (1997). Mapping the big piCtture: Integrating curriculum

& assessmtent K-12. Alexandria, VA. Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

Lowell-York, J., Doyle, M. E., & Kronberg, R. (1995). Curriculum as

everytbing students learn in scbool: Individualizing learning opportzni-

ties. Baltimore: Brookes.

VOL. 39, rUO. 3. JAIIUARY 2DO4 161

Appendix C Research Text 1

Curriculum Mapping in Higher Education:

AVehicle for Collaboration

Kay Pippin Uchiyama & Jean L. Radin

Published online: 24 June 2008

#

Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2008

Abstract This qualitative study makes the case for the implementation of curriculum

mapping, a procedure that creates a visual representation of curriculum based on real time

information, as a way to increase collaboration and collegiality in higher education.

Through the use of curriculum mapping, eleven faculty members in a western state

university Teacher Licensure program aligned and revised the teacher education curriculum

across a sequence of courses. An increase in collaboration and collegiality among faculty

emerged as an unintended outcome as a result of participation in the project.

Key words curriculummapping

.

collaboration

.

collegiality

.

higher education

To go fast, go alone. To go farther, go together. (African proverb)

The norms of the higher education community at large encourage autonomy and

independence. Junior faculty often speak of the loneliness and isolation that they encounter

Innov High Educ (2009) 33:271280

DOI 10.1007/s10755-008-9078-8

Kay Pippin Uchiyama is currently the Assessment Coordinator for the Poudre School District in Fort

Collins, Colorado. During this study, she was an Assistant Professor of Teacher Education at Colorado

State University and a co-primary investigator for the Preparing Tomorrows Teachers to Use Data

grant. She received her Ph.D. in Instruction and Curriculum in the Content Areas with an emphasis on

Teacher Education and Learning to Teach from the University of Colorado at Boulder. Her interests

include data driven instruction, assessment for learning, teacher education, professional development

schools, and mathematics education. Her email is kuchiyam@psdschools.org.

Jean L. Radin is an adjunct professor at Colorado State University and a co-primary investigator for the

Preparing Tomorrows Teachers to Use Data grant. She received her Ph.D. from Colorado State University.

Her interests are brain-based teaching and learning, data driven instructional practices, teacher education

and professional development schools. Her email is jradin@cahs.colorado.edu.

K. P. Uchiyama (*)

Poudre School District, 513 Skysail Lane, Fort Collins, CO 80525, USA

e-mail: mkuchiyama@comcast.net

J. L. Radin

Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

e-mail: jean.radin@colostate.edu

Appendix D Research Text 2

and frequently cite this as a reason for leaving an institution (Barnes et al. 1998). Tierney

and Rhoads (1994) found that a lack of a sense of community was a key determinant in the

decision to leave academia. Trower noted, the single most important concern [of faculty]

was autonomy in the workplace (as cited in Fogg 2006, p. 1). Furthermore, in the pursuit

of tenure and promotion, single-authored publications are more highly rated than are those

with two or more authors, which can add to the pressure and sense of isolation. As Palmer

(1998) summarized,

Academics often suffer the pain of dismemberment. On the surface, this is the pain of

people who thought they were joining a community of scholars but find themselves in

distant, competitive and uncaring relationships with colleagues [emphasis added] (p. 20).

Organizations beyond higher education have shifted toward cultures where the norms of

autonomy and independence are replaced by the norms of collegiality and collaboration.

For example, the U.S. Department of Labor (1991) established skills and competencies for

the workplace; and two of these elements, sociability and interpersonal skills, directly relate

to norms of collegiality and collaboration. Sociability is defined as demonstrate[ing]

understanding, friendliness, adaptability, empathy, and politeness in group settings (U.S.

Department of Labor 1991, p. x). Interpersonal skills are defined as participate[ing] as a

member of a team, contributing to group efforts, negotiation, working toward agreement,

and resolving divergent interests (U.S. Department of Labor 1991, p. xi). Employers have

identified these two elements as desirable traits for the workplace.

Tierney (1999) compared the values and norms of higher education to those of the

workplace. He argued that the values of competition and individualism in higher education

are replaced by cooperation and teamwork outside of the higher education arena. He also

argued that the culture of higher education encourages employees to fly solo whereas

most workplace organizations expect their employees to fly in formation (Tierney 1999).

Whereas in higher education individuals often complete their own projects in isolation which

may or may not have relevance to the departments or schools goals, workplace

organizations tend to rely on teams that work together toward a common goal (Tierney 1999).

While it is not universally true that the culture of higher education is individualistic,

experts in the field of higher education research suggest that, in order to survive, the culture

must shift from one that values individualism and autonomy to one that values collegiality

and collaboration (Simpson and Thomas as cited in Van Patten 2000; Tierney 1999). Fogg

(2006) reported that collegiality is an important factor in job satisfaction for todays junior

professors, often more important than salary. Furthermore, funding organizations encourage

collaborations between and among individuals, departments, institutions of higher

education, and the community. For example, the National Science Foundation Grant

Proposal Guide (2007) encourages group proposals and interdisciplinary projects with

specific funding solicitations often requiring collaborations.

This article describes a project where eleven school of education faculty members used

curriculum mapping to align and integrate the curriculum across a sequence of courses.

Curriculum mapping is a procedure which promotes the creation of a visual representation

of curriculum based on real time information (Jacobs 1997). Using a template with

predetermined categories and format, instructors map their curriculum as it occurs, in real

time. Real time in this context means when the curriculum is delivered, rather than as

projected in a course syllabus prior to the course or after the course is completed. The

curriculum maps are aggregated first horizontally by course and then vertically across all

courses in a sequence. All faculty members review the maps, identifying strengths, gaps,

272 Innov High Educ (2009) 33:271280

Appendix D Research Text 2

and overlaps. Once the review is complete, the faculty determines what and where to add or

eliminate content and/or strategies, which results in a more streamlined curriculum and

integrated program. These maps become living documents for course instructors; and they

can be frequently revisited and revised as courses are adapted to the needs of the established

curriculum, the needs of students, or the incorporation of new instructors into the program.

While the original intent of our project was to align and revise the teacher education

curriculum, an unexpected and beneficial outcome emerged: we found that collaboration

and collegiality increased as a result of participation in the project. To explain this outcome,

we first define the meaning of collaboration and collegiality as it applies in the context of

the curriculum mapping process. Next, we describe how the process was implemented

including background information, a rationale for selecting curriculum mapping, and

methods of data collection. Our findings follow; and finally, we share our conclusions, and

implications.

Collaboration and Collegiality

In any community, collaboration and collegiality are sought after ideals. Haworth and

Conrad (1997) noted that collegial and supportive cultures are an important component of

high quality programs. As Grossman et al. (2001) eloquently explained, The association

between community and the good life reaches across religious, cultural, and philosophical

traditions where the value of individuals working together for the common good is upheld

and respected (p. 945). The English language is replete with common sayings that

illustrate the values of collegiality and collaboration. For example, united we stand,

divided we fall, many hands make light work, and circle the wagons. Other examples

come from famous individuals in history. Isaac Newton (1675) wrote, If I have seen

further than others, it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants (as cited in Kaplan 1992),

and Henry Ford (n.d.) the developer of the assembly line stated, If everyone is moving

forward together, then success takes care of itself (Thinkexist.com 2008). In short, these

values allow communities to function and grow productively.

For this article we use the following definitions: collegialitycooperative interaction

among colleagues and collaborationto work together, especially in a joint intellectual

effort (www.Dictionary.com).

The values of collegiality and collaboration are embedded in the curriculum mapping

process by providing a structure for all to engage in collective dialogue about the

curriculum, instruction, and students learning (Donald 1997; Udelhofen 2005). Curriculum

mapping fosters respect for the professional knowledge and expertise of all instructors. It

allows all participants to examine, or re-examine, their individual and collective beliefs

about teaching and learning in a structured and safe setting.

The Process of Curriculum Mapping

Curriculum mapping is a cyclical process that consists of five stages. Figure 1 provides a

graphic representation of this process. In Stage 1, individual instructors develop maps of

their courses in real time as they teach over the span of a semester. Stage 2 begins with all

instructors of a particular course working together to aggregate the maps. In Stage 3, all

faculty members involved review all the maps in a program or set sequence of courses. If

Innov High Educ (2009) 33:271280 273

Appendix D Research Text 2

the number of faculty members or the number of instructors per course is small, this can be

done as one large group. If not, Jacobs (1997) suggested creating a number of heterogeneous

groups consisting of those who represent all courses and having these groups review the

vertical array of maps, looking for alignment, gaps, overlaps, inconsistencies, and strengths.

A representative from each group records the findings, aggregates them, and then reports

out to the large group. Stage 4 includes all faculty members and focuses on identifying

areas in need of alignment, revision, and/or elimination. The group prioritizes those areas

that need attention first and those that need further study. The group then develops a plan

following with action in Stage 5. The process comes full circle in Stage 6. The result is a

curriculum that is fluid and adaptable as the needs of students, policies, and new research

findings change over time.

The Project

This section details background information leading up to the project, the sequence for

implementation of curriculum mapping, data collection for documentation, and data

analysis.

Background of the Project

In the fall of 2005, the School of Education (SOE) at an institution in a western state was

part of a grant project involving four institutions of higher education across the state. This

project focused on developing and integrating data driven instructional practices into

Teacher Licensure curricula. As part of the grant, the four institutions together developed

Information-Based Educational Practice (IBEP) standards, which accurately described the

Stage 1

Develop Individual Maps

for each course

Stage 6 Stage

Repeat the process Review and aggregate

maps (horizontally) by course

State 5 Stage 3

Revise courses and Aggregate the maps

implement revisions (horizontally) by course

Stage 4

The group identifies strengths,

gaps, overlaps, etc.

2

Fig. 1 The process of curriculum mapping.

274 Innov High Educ (2009) 33:271280

Appendix D Research Text 2

process of data driven instruction. From there, each institution determined its own methods

for data collection and procedures for the integration and implementation of the IBEP

standards into the curriculum.

At our institution we, as the primary investigators for the grant and members of the

licensure faculty, needed to establish if, where, and when the IBEP standards occurred in

the Teacher Licensure programs course sequence. To do that meant closely examining the

curriculum in place. We were aware that K-12 schools and districts were using curriculum

mapping to form a picture of their curriculum, so we decided to employ the same process.

We recognized that this work would mean a change in how the Teacher Licensure faculty

operated. As Jacobs (2004) had stated, [through curriculum mapping] colleagues create

new pathways in a shared profession (p. x). First, we examined the current literature on

change to structure this process. We drew heavily on Fullans (2001) work, noting that

successful change depends on shared meaning among all involved. While the Teacher

Licensure faculty members were all involved with preparing pre-service teachers though a

set course sequence, the challenge was to create shared meaning and buy-in to the project.

Sequence for Implementation of Curriculum Mapping

We had a two-year time period based on our grant funding. To facilitate the work, we

organized to follow the university semester system. During the first semester, we developed

a timeframe for the work and identified and planned the use of available technology for

implementation. We also reviewed and aligned the licensure programs foundation and

belief statements with our states Department of Education Performance-Based Teacher

Education Standards, the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education

standards, principles from the Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium

standards, performance indicators from our states Council on Higher Education, and the

Information-Based Educational Practice Standards developed by the four institutions. The

result was a written document that outlined our program. However, having a written

document was no guarantee that these standards and beliefs were translated into our teacher

education courses. We also suspected that course syllabi might or might not reflect what was

actually implemented in the classroom. For example, when we reviewed the course syllabi,

we found that not all faculty members were teaching to the states performance standards for

teachers, even though these standards were mandated. In fact, one colleague commented

during a licensure faculty meeting discussion, Teach to standards? What happened to

academic freedom? At this point, we knew mapping the curriculum would provide a forum

for sharing, discussing, analyzing, and realigning coursework with standards.

Using data to develop commitment. Research has shown that change takes place at the

individual level prior to the organizational level (Hall and Hord 2006, p. 7). In order for

change to be successful, there must be pressure and support for those engaged in the change

(Fullan 2001). We knew we needed to instill a sense of urgency to show licensure faculty

members that change was necessary so we reviewed student satisfaction data such as

individual course evaluations. These data indicated that students felt there was considerable

overlap and repetition among the courses in the program sequence. An upcoming state

accreditation visit and a national accreditation visit also provided pressure to review the

current curriculum. Using data to inform practice was an ongoing theme of our work.

Inviting participation, constructing a timeframe, collecting data. We provided support for

change by using existing scheduled meetings to inform the licensure faculty about the data

Innov High Educ (2009) 33:271280 275

Appendix D Research Text 2

and the process of curriculum mapping, by offering professional development activities to

help implement the mapping process, and by disseminating handouts and articles. We also

offered small stipends from the grant monies to those who volunteered to engage in the

work. At the beginning of the project, nine instructors of two key licensure courses in the

six-course sequence volunteered to participate in the process. In return, over the two-year

period of the project, these participants agreed to map their courses for a minimum of one

semester in real time, attend meetings to aggregate the maps, complete an open ended

survey of the process, and participate in an end of the project interview.