Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Understanding Consumer Attitudes On Edible Films and Coatings A Focus Group Findings Dial Corp 2006 Journal Sensory SC

Uploaded by

Xochitl Ruelas Chacon0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views14 pagesEdible films and coatings (EFCs) are one of the innovations of packaging technology aimed to improve food quality and to retain freshness of food. A focus group study was conducted to understand consumer attitudes, opinions and concerns toward EFCs. The main findings from this study shed light to the important steps to consider when commercializing EFC applications.

Original Description:

Original Title

Understanding Consumer Attitudes on Edible Films and Coatings a Focus Group Findings Dial Corp 2006 Journal Sensory Sc

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEdible films and coatings (EFCs) are one of the innovations of packaging technology aimed to improve food quality and to retain freshness of food. A focus group study was conducted to understand consumer attitudes, opinions and concerns toward EFCs. The main findings from this study shed light to the important steps to consider when commercializing EFC applications.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views14 pagesUnderstanding Consumer Attitudes On Edible Films and Coatings A Focus Group Findings Dial Corp 2006 Journal Sensory SC

Uploaded by

Xochitl Ruelas ChaconEdible films and coatings (EFCs) are one of the innovations of packaging technology aimed to improve food quality and to retain freshness of food. A focus group study was conducted to understand consumer attitudes, opinions and concerns toward EFCs. The main findings from this study shed light to the important steps to consider when commercializing EFC applications.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

UNDERSTANDING CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS

AND COATINGS: FOCUS GROUP FINDINGS

VICKI CHEUK-HANG WAN

1

, CHOW MING LEE

2

and SOO-YEUN LEE

2,3

1

Dial Corporation

Scottsdale, AZ

2

Food Science and Human Nutrition Department

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

905 S. Goodwin Ave., MC-182

Urbana, IL 61801

Accepted for Publication October 3, 2006

ABSTRACT

The application of edible lms and coatings (EFCs) is one of the inno-

vations of packaging technology aimed to improve food quality and to retain

freshness of food. In order to maximize the potential of a new technology, it is

important to consider consumer concerns and acceptance. Therefore, a focus

group study was conducted to understand consumer attitudes, opinions and

concerns toward EFCs. Furthermore, innovative applications of EFCs in

different food systems were probed during the focus group discussions. Four

independent focus groups (n = 27) were conducted with each group consisting

of ve to eight consumers who are frequent grocery shoppers. Consumers were

concerned about the types of products that are coated, safety of the coating

materials, sensory qualities of the resulting products, end benets of EFCs and

the cost of the food products packaged with EFCs. This research presents

insights on the issues to address when commercializing EFC applications.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

This study demonstrates the effective utilization of qualitative consumer

testing such as focus group when probing the consumer attitudes and accep-

tance toward novel food processing or packaging technologies, which include

edible lms and coatings (EFCs). The main ndings from this study on EFCs

shed light to the important steps to consider when commercializing EFCs,

which are to evaluate sensory attributes of integrated coated products, to

3

Corresponding author. TEL: 217-244-9435; FAX: 217-265-0925; EMAIL: soolee@uiuc.edu

Journal of Sensory Studies 22 (2007) 353366. All Rights Reserved.

2007, The Author(s)

Journal compilation 2007, Blackwell Publishing

353

properly label ingredients of EFCs with a focus on marketing the natural

ingredients added and to target marketing strategies to advertise direct con-

sumer benets of the resulting EFC products.

INTRODUCTION

Edible lms and coatings (EFCs) have been shown to improve quality and

extend shelf life of food products by acting as barriers of gases, moisture,

odors and lipids (Kester and Fennema 1986). They can be made of different

macromolecules such as soy proteins (Gennadios and Weller 1991), whey

proteins (McHugh et al. 1994), polysaccharides (Nisperos-Carriedo 1994),

and combination of proteins and lipids (Weller et al. 1998). Researchers in the

last decade have focused on investigating functional properties of edible lms

such as mechanical and water barrier properties, and solubility in various

solvents with different modications. It was found that protein lms have

limited water barrier properties but good oxygen and lipid barrier properties

(Krochta 1992). Edible coatings have been applied to different food products

such as fruits (Park 1999), peanuts (Lee et al. 2002a), chocolate-covered

almond pieces (Lee et al. 2002b), carrots (Mei et al. 2002) and deep-fried

products (Mallikarjunan et al. 1997; Albert and Mittal 2002). However, no

study has been reported to probe consumer attitudes and concerns toward the

use of EFCs in food products.

In order to successfully market new products or technologies, it is impor-

tant to consider consumer opinion (Best 1991). Many factors eventually affect

consumers purchase intent of food products. These factors include intrinsic

sensory attributes such as appearance, taste, avor and texture, and extrinsic

factors such as price, convenience, nutritional content, hygienic standards and

packaging (Deliza et al. 2003). Such extrinsic factors cannot be readily iden-

tied using quantitative consumer methods and researchers rely on qualitative

methods like focus group to understand consumer behavior.

Focus groups are generally used in the early stages of product develop-

ment and market research to probe consumer reaction to the new product or

concept (McQuarrie and McIntyre 1986; Sheth et al. 1999; Langford and

McDonagh 2003). Focus group also acts as a bridge between laboratory and

quantitative consumer tests (McNeill et al. 2000). Back in 1996, when irra-

diation of food products received a lot of consumer attention, a focus group

study was conducted to determine consumer attitude and consumer-friendly

communication language to promote the consumption of irradiated poultry

(Hashim et al. 1996). It was found that consumers were aware of the irradia-

tion technology, but they wanted more information to understand its advan-

354 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

tages and disadvantages. The study suggested that education, informative

labels, posters and in-store sampling were effective ways to encourage con-

sumers to buy irradiated poultry.

Results obtained from focus group can also be used to construct ques-

tionnaires for subsequent quantitative analysis. In the study of Brug et al.

(1995), the focus group methodology was utilized to identify beliefs that are

important in consumption of fruits and vegetables in the Netherlands, such as

perceived health benets and taste. The results were used to develop a ques-

tionnaire to measure responses of larger populations. Focus group use was

shown to be a reliable method to understand consumer behavior (Stewart et al.

1994) and to determine quality criteria of products (Galvez and Resurreccion

1992; McNeill et al. 2000).

The number of participants in a focus group varies among researchers,

including 6 to 9 (Casey and Krueger 1994), 8 to 12 (Chalofsky 1999) and 5 to

10 (Krueger 2002). Krueger and Casey (2000) recommend six to eight par-

ticipants for most noncommercial topics. Mini focus groups, consisting of four

to six participants are becoming popular because they are easier to set up and

are more comfortable for the participants in sharing their opinions (Krueger

and Casey 2000). A moderator, who is usually trained and experienced,

follows a series of previously planned questions and makes sure that the

discussion is not off tracked (Lawless and Heymann 1999). The moderator

must also establish an environment that is friendly and permissive (Krueger

2002).

Focus groups not only have the advantage of being able to probe in-depth

questions on a specic topic which cannot be done otherwise with quantitative

consumer tests, but also have the advantage of allowing for new topics and

ideas to be brought up by the interaction among the participants (Stewart and

Shamdasani 1991). This methodology has been found to be suitable for studies

involving problem identication, planning, product development, implemen-

tation of new product or service, evaluation, marketing and research on topics

that require interaction among respondents which cannot be effectively

explored using individual interviews, survey or participant observations

(Chalofsky 1999).

However, focus groups also have shortcomings. The moderator must be

experienced enough to encourage every subject to participate and not let one

or two members dominate the group. Furthermore, the results are difcult to

analyze and interpret because they are qualitative. Casey and Krueger (1994)

suggested having more than one person analyze the data in order to minimize

personal biases. By using code words, Stewart et al. (1994) was able to

summarize the discussions into a smaller list of factors affecting food choices.

The objectives of this study were to (1) investigate consumer awareness

and attitudes toward EFCs; (2) determine the factors that affect buying intents

355 CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS AND COATINGS

of food products coated with EFCs; and (3) contrive innovative ideas to

commercially utilize EFCs in food processing and manufacturing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Four focus groups were conducted with eight, eight, six and ve partici-

pants in each group, respectively. The groups consisted of nine males and 18

females; 16 of them were in the age group of 1825, and 11 of them were in

the age group of 2565. All participants were frequent grocery buyers and

most of them go to the grocery store at least once a week. Each group was

moderated by the same moderator with experience in moderating focus

groups.

Procedure

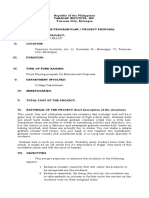

A discussion guideline (Fig. 1) was designed following the recommen-

dations of Lawless and Heymann (1999). The moderator rst introduced

herself and stated the ground rules of focus group, in which the participants

should respect others opinions and only one person should speak at a time.

Then, the participants were informed that the sessions were recorded with

audio and video aids.

In order to get everyone acquainted with one another and to get the

participants thinking about the topic of interest, each of the participants was

asked to state his/her name and briey discuss one concern that he/she had

about keeping his/her food products fresh. If the participant talked at the

beginning of the session, it is more likely that he or she will participate more

in the discussion (Casey and Krueger 1994). The warm-up exercise also made

the environment less threatening and more permissive.

After the warm-up phase, a handout with a statement about EFCs was

distributed to the participants (Fig. 2). Participants were then asked about their

awareness, attitudes, and concerns about buying and consuming food products

with edible coatings. The focus group was facilitated by the moderator and by

the assistant moderator who was responsible for recording the sessions.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The results were analyzed and interpreted by adapting the six-step

method recommended by Casey and Krueger (1994). All materials including

video tapes, audio tapes and notes of all groups were collected and reviewed.

Responses for each question were examined. Similarities and differences

356 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

Time: 11.5 hours

I. Introduction

A. Introduce self

B. Ground rules:

1. Free to participate or not participate at any time

2. One person talking at a time

3. Respect others opinions

C. Taping of the focus group

II. Warm-up: To get everyone acquainted with one another and to get us all thinking

about the topic of interest, please

A. State your name

B. Briefly discuss one concern you have about keeping your food fresh (e.g., I hate

when my soda goes flat after I open the bottle)

III. Initial questions

A. Awareness

1. Have you heard of edible coating?

2. What are some applications for edible coatings that you can think of?

3. What are your thoughts about how it affects the food product?

IV. Definition of biodegradable and edible coatings (Fig. 2) and further probing of

consumer issues for EFC

A. Attitudes and Concerns

1. Do you have any questions about EFC? (e.g., what it is made of .)

2. What are your attitudes about edible coating? What concerns do you have

about edible coating (e.g., safety, nutritional, chemical hazard, digestibility,

allergy)?

3. Do you want your food products packaged with edible coatings?

4. Would you rather buy a coated or uncoated product?

5. What factors determine whether you buy a food product with edible coating or

not?

6. Ask for innovative product application with EFC.

B. Labeling concerns

1. If a product is packaged with edible coating, how should it be advertised?

2. How should EFC be labeled? What information should be included?

V. Clarification and conclusion

A. If you would like more information about edible films and coating, you can

B. Thank you for your time

FIG. 1. DISCUSSION GUIDELINE FOR THE FOCUS GROUP ON EDIBLE FILMS AND

COATINGS (EFCs)

357 CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS AND COATINGS

among groups were identied and reported. To minimize personal bias, results

were then discussed and summarized by the moderator and the principal

investigators of the study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

When asked about their awareness of edible coatings (question III.A,

Fig. 1), most of the participants had never heard of EFCs before the discussion.

Wax coating on apples was the example that was brought up most frequently.

When the example of M&M sugar coating was discussed as one of the

examples of edible coatings, the participants quickly made the distinction

between the coatings that served as an integral part of the product and the

coatings that were applied as an addition to the product to extend shelf life or

to improve sensory properties. They regarded the sugar coating of M&M as an

integral part of the product and as a necessity.

Participants had both positive and negative views of EFC applications in

food products (question IV, Fig. 1). Consumers were concerned about the

safety and sensory attributes of the coated products, as well as the types of

products that are coated (Table 1). Furthermore, the additional cost and per-

ceived benets were also factors affecting the purchase intent for the coated

products (Table 1).

Types of Product

Consumer attitudes toward the applications of EFCs to food products

were rst probed after the explanation of EFCs was given (question IV.A.2 and

3). Participants were also asked if they would purchase coated food products

Biodegradable and edible coating

Biodegradable means the material is capable of being broken down by the action of living

things such as microorganism. Edible means the material is safe to eat. Coating is a layer of

one substance covering another, in this case, covering a food product. The objectives of

applying a coating to a food product are to extend the shelf life and improve quality of the

food products by acting as a barrier (moisture and/or gas) or providing gloss (shine). It is

usually made with proteins, lipids or polysaccharides or combinations of those

macromolecules with other chemicals added, depending on the objectives of the coating.

FIG. 2. DEFINITIONS OF BIODEGRADABLE AND EDIBLE COATINGS PROVIDED TO

THE PARTICIPANTS

358 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

(question IV.A.4 and 5). Most of the consumers responded that they had to

know the types of products that were coated before they could make the

decision. This implied that consumers might have different degrees of accept-

ability for different products being coated. They expressed that they were more

likely to purchase a coated product if the product itself has a natural outer

layer which can be removed before it is consumed (Table 1). Examples that

were suggested were fruits, such as apples, oranges and bananas. The ease of

removing the coating from the product was a concern. Consumers expressed

that there should be instructions on the package showing how they could

remove the coating.

Safety

Safety of the coated product was the second concern brought up during

the discussion. Concerns of safety included the ingredients of the coating and

the handling of the coated products. First, participants demanded that the

coated products should be labeled as Coated, as well as the ingredients of

coatings listed on the products label. As stated by Best (1991), technologies

that are applied to food products should not be invisible to consumers.

The participants also expressed their preference for EFCs made with

natural rather than articial ingredients. Because EFCs are generally made

with proteins, polysaccharides and/or lipids from natural source, it may be

benecial to inform the consumers that the major ingredients of the coatings

are natural. Prescott et al. (2002) also reported that Japanese, Taiwanese and

Malaysian panelists placed natural content (natural ingredients with no addi-

tives or articial ingredients) as the most important motivation in food choice.

TABLE 1.

FACTORS AFFECTING PURCHASE INTENT OF FOOD PRODUCTS COATED WITH

EDIBLE COATINGS

Factor Description Discussion

Type of product Natural outer layer Outer layer which could be removed favored

Safety Ingredient of edible coating Labeling issue, natural ingredients favored,

allergy issue

Handling of coated product Microbial contamination issue

Sensory attribute Taste, avor and texture Assessment of the changes that were

made required

Appearance Issue of not being able to determine quality

because of changes in appearance

Perceived benet Manufacturers benet Extending shelf life

Consumer benet Added convenience

Improvement in overall quality

Cost Higher price Accepted if consumers benets were obvious

359 CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS AND COATINGS

Decreased purchase intent was observed for genetically modied products as

they were perceived as unnatural (Frewer et al. 1996). Absence of chemicals

was also one of the reasons why people bought organic foods (Schifferstein

and Oude Ophuis 1998).

Ingredients that cause allergies were also a concern among the focus

group participants. There are 2% of the general population and 8% of child

population who have some form of food allergy (Ortolani et al. 2001). There-

fore, listing all the coating ingredients was indicated as important. For the

participants who were vegetarians, listing the ingredients to verify the non-

animal source was also an important factor.

The safety of food products could be improved by incorporating antimi-

crobial agents into the coatings to reduce the risks of microbial contamination

of the products. Surprisingly, participants were concerned that the coated

products may encourage production, distribution or retail employees to be

careless with sanitation.

Sensory Quality

Besides the safety of coated products, the participants were also con-

cerned about the sensory quality of coated products. If the purpose of the

coatings was to extend shelf life, the majority of our panel expressed that the

coating should not have any taste or odor, and it should be transparent.

However, they welcomed the idea of applying coatings as carriers of avors for

new product development.

Taste, avor and texture are often considered the most important

attributes of foods. Taste satisfaction was an important motivation for Dutch

people to consume fruits and vegetables (Brug et al. 1995). They are the major

drivers of meat consumption (Verbeke and Vackier 2004) and they also con-

tribute to the acceptance of different variety of apples (Jaeger et al. 1998).

However, not many studies have been conducted to investigate the sensory

properties of EFC-coated products. Descriptive analysis was utilized to evalu-

ate different sensory attributes of peanuts coated with whey protein (Lee et al.

2002a). Perceived rancidity of coated peanuts was signicantly less than that

of uncoated peanuts. Glossiness and gloss stability of chocolate-covered

almond pieces coated with whey protein were measured, and they were com-

parable to the shellac coating which is currently used in the confectionery

industry (Lee et al. 2002c). Coated carrots were found to have improved

appearance and similar fresh aroma and avor to uncoated carrots (Mei et al.

2002). Sensory attributes of lms made with whey protein isolate (WPI) and

candelilla wax emulsions were also evaluated (Kim and Ustunol 2001). Emul-

sion lms were opaque, slightly sweet and adhesive with no pronounced milk

avor, while lms with no wax incorporated were transparent.

360 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

Appearance is another important measure of food quality. Due to the

concerns of not being able to appraise the quality of the food products that

are coated, the participants expressed their preference toward transparent

edible coatings (Table 1). Our ndings agree with that of Bredahl et al.

(1998) and Jaros et al. (2000). However, many studies have shown that coat-

ings affect the appearance of coated products. Lee et al. (2002a) reported

that WPI-coated peanuts were darker than uncoated peanuts. Furthermore,

emulsion lms of WPI and candelilla wax are opaque in appearance (Kim

and Ustunol 2001).

Perceived Benets

In an article by Booth (1995) about the cognitive basis of quality, shelf

life was regarded as one of the important factors of quality. Normally, one

would think the longer the shelf life, the better the quality. However, in this

study, participants had different opinions when they were informed that

products coated with EFCs may have extended shelf life.

Coated products with extended shelf life were perceived as value-added

products in the following situations: (1) for consumers who cannot nish the

products in a short time period and want the product to be fresh for a longer

time on the shelf; (2) for consumers who pay less attention to keeping food

fresh (i.e., less likely to clip a bag of chips, or close the lid of a container); (3)

for produce that is not always in season, and therefore, for which coating can

extend the availability of these products throughout the year; and (4) for

perishable foods which need to withstand longer transportation duration.

However, for participants who go to the grocery store more than twice a week,

the extended shelf life of coated products was not as appealing. They preferred

fresher products over coated products that were placed on the shelf for pro-

longed period. Furthermore, they suspected the extension of shelf life of the

products actually was more benecial to the manufacturers and retailers than

to the consumers. Similarly, Frewer et al. (1997) found that consumers were

less likely to buy cheese that was produced in a shorter period of time because

they perceived that was benecial to the producers rather than to the consum-

ers or the environment.

Another benet associated with coated products was convenience. EFC-

coated sliced cheese was an example suggested by the focus group panel of

added convenience compared to a block of cheese or sliced cheese which

requires the removal of the plastic wrapping. For participants with children,

they were willing to pay extra for the coated products that are more natural and

convenient. Compared to the general public, elderly consumers with higher

disposable income may be targeted for genetically engineered products with

environmental or health benets at a higher price (Deliza et al. 1999).

361 CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS AND COATINGS

Cost

Cost was another factor participants were concerned with when discuss-

ing EFCs. Most of the consumers would choose to buy the less expensive

product, if the coated and uncoated products had the same qualities and

benets. However, if the participants perceived the coated products as value-

added products, they were willing to pay higher price for the coated products

if the benets were obvious (Table 1).

Finally, consumers were asked to discuss and provide examples of inno-

vative product applications using EFCs (question IV.A.6, Fig. 1). The sug-

gested products were divided into three broad categories: dairy, bakery and

snack products. Within the dairy category, sliced cheese was recommended to

be individually coated with edible coating instead of the plastic wrap that is

currently used in the market. One of the innovative applications brought up

within the dairy category was replacing the foil seal of yogurt package with a

layer of edible lm. After removing the plastic cap, consumers could just break

the edible seal to consume the yogurt. Both of the applications within the dairy

category were aimed to provide convenience and to decrease the use of

nonbiodegradable plastic packaging materials.

Participants also came up with ideas on bakery products that are vulner-

able to deterioration and have a relatively short shelf life (<2 weeks). For

consumers that are not able to consume the whole bag of bread before the

sell-by date, a possible application proposed was to coat the inner side of the

bread package with antimicrobial agent-incorporated edible coating to extend

shelf life.

Because fried snacks, such as potato chips, are susceptible to lipid oxi-

dation and moisture gain, which result in deterioration of quality, participants

discussed the application of EFCs to provide oxygen and moisture barrier

function on such products. Candies packaged in a primary package were

mentioned as potential products to be coated to decrease the stickiness and to

ease the handling of the candy pieces.

Results from this study strongly suggested that it is important to evaluate

sensory attributes of actual coated food products, in addition to investigating

basic chemical and physical properties of edible lms, the latter being

researched extensively. This study also suggested that the natural ingredients

of EFCs should be properly labeled and advertised, and the marketing direc-

tion of coated products should be focused on how to convey the potential

benets of the coated products to the consumers. Future studies could include

conducting sensory discrimination tests on the integrated coated products to

investigate whether the consumers could distinguish between the coated and

the uncoated products, or between the coated products manufactured by dif-

ferent coating materials and processing methods. Additionally, preference tests

362 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

could be conducted to determine if the coated product is liked as well as the

uncoated product or which coated product is preferred the most. Future focus

group studies can investigate the relationship between the different labels of

coated products and changes in consumer purchase intent.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this study suggest that besides focusing on investigating

basic chemical and physical properties of edible lms, it is also very important

to evaluate sensory attributes of integrated coated products. This study also

suggested that the natural ingredients of EFC should be properly labeled and

advertised, and the marketing direction of coated products should be focused

on how consumers would benet from the coated products. Future studies

could include conducting sensory discrimination tests on the actual products to

investigate whether the consumers could distinguish between coated and

uncoated products, and preference tests to determine which product is pre-

ferred by the consumers. Additional focus group studies may also be con-

ducted to investigate the relationship between the different labels of coated

products and consumer purchase intent.

REFERENCES

ALBERT, S. and MITTAL, G.S. 2002. Comparative evaluation of edible

coatings to reduce fat uptake in a deep-fried cereal product. Food Res. Int.

35, 445458.

BEST, D. 1991. Designing new products from a market perspective. In Food

Product Development (E. Graf and I.S. Saguy, eds.) pp. 128, AVI Book,

New York, NY.

BOOTH, D.A. 1995. The cognitive basis of quality. Food Qual. Prefer. 6,

201207.

BREDAHL, L., GRUNERT, K.G. and FERTIN, C. 1998. Relating consumer

perceptions of pork quality to physical product characteristics. Food

Qual. Prefer. 9, 273281.

BRUG, J., DEBIE, S., VANASSEMA, P. and WEIJTS, W. 1995. Psychosocial

determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among adults: Results of

focus group interviews. Food Qual. Prefer. 6, 99107.

CASEY, M.A. and KRUEGER, R.A. 1994. Focus group interviewing. In

Measurement of Food Preferences (H.J.H. Mace and D.M.H. Thomson,

eds.) pp. 7796, Chapman & Hall, New York, NY.

363 CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS AND COATINGS

CHALOFSKY, N. 1999. How to Conduct Focus Group, American Society for

Training & Development, Alexandria, VA.

DELIZA, R., ROSENTHAL, A., HEDDERLEY, D., MACFIE, H.J.H. and

FREWER, L.J. 1999. The importance of brand, product information and

manufacturing process in the development of novel environmentally

friendly vegetable oils. J. Int. Food Agribusiness Marketing 10(3), 6777.

DELIZA, R., ROSENTHAL, A. and SILVA, A.L.S. 2003. Consumer attitude

towards information on non-conventional technology. Trends Food Sci.

Technol. 14, 4349.

FREWER, L.J., HOWARD, C. and SHEPHERD, R. 1996. The inuence of

realistic product exposure on attitudes towards genetic engineering of

food. Food Qual. Prefer. 7, 6167.

FREWER, L.J., HOWARD, C., HEDDERLEY, D. and SHEPHERD, R. 1997.

Consumer attitudes towards different food-processing technologies used

in cheese production the inuence of consumer benet. Food Qual.

Prefer. 8, 27180.

GALVEZ, F.C.F. and RESURRECCION, A.V.A. 1992. Reliability of the focus

group technique in determining the quality characteristics of mungbean

[Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczec] noodles. J. Sensory Studies 7, 315326.

GENNADIOS, A. and WELLER, C.L. 1991. Edible lms and coatings from

soymilk and soy protein. Cereal Foods World 36, 10041009.

HASHIM, I.B., RESURRECCION, A.V.A. and MCWATTERS, K.H. 1996.

Consumer attitudes toward irradiated poultry. Food Technol. 50,

7780.

JAEGER, S.R., ANDANI, Z., WAKELING, I.N. and MACFIE, H.J.H. 1998.

Consumer preferences for fresh and aged apples: A cross-cultural com-

parison. Food Qual. Prefer. 9, 355366.

JAROS, D., ROHM, H. and STROBL, M. 2000. Appearance properties a

signicant contribution to sensory food quality. Lebensm-Wiss. Technol.

33, 320326.

KESTER, J.J. and FENNEMA, O.R. 1986. Edible lms and coatings: A

review. Food Technol. 40(12), 4759.

KIM, S.J. and USTUNOL, Z. 2001. Sensory attributes of whey protein isolate

and candelilla wax emulsion edible lms. J. Food Sci. 66, 909911.

KROCHTA, J. 1992. Control of mass transfer in foods with edible coatings

and lms. In Advances in Food Engineering (R.P. Singh and M.A.

Wirakartakusumah, eds.) pp. 517538, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

KRUEGER, R.A. 2002. Designing and conducting focus group interviews.

http://www.whatkidscando.org/studentresearch/2005pdfs/

Kruegeronfocusgroups.pdf (accessed May 1, 2006).

KRUEGER, R.A. and CASEY, M.A. 2000. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide

For Applied Research, 3rd Ed., Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

364 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

LANGFORD, J. and MCDONAGH, D. 2003. Introduction. In Focus Groups

(J. Langford and D. McDonagh, eds.) pp. 120, Taylor & Francis, New

York, NY.

LAWLESS, H.T. and HEYMANN, H. 1999. Qualitative consumer research

methods. In Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices (R.

Bloom, ed.) pp. 519546, Aspen Publication, Gaithersburg, MD.

LEE, S-Y., TREZZA, T.A., GUINARD, J.X. and KROCHTA, J.M. 2002a.

Whey-protein-coated peanuts assessed by sensory evaluation and static

headspace gas chromatography. J. Food Sci. 67, 12121218.

LEE, S-Y., DANGARAN, K.L. and KROCHTA, J.M. 2002b. Gloss stability

of whey-protein/plasticizer coating formulations on chocolate surface.

J. Food Sci. 67, 11211125.

LEE, S-Y., DANGARAN, K.L., GUINARD, J.X. and KROCHTA, J.M.

2002c. Consumer acceptance of whey-protein-coated as compared with

shellac-coated chocolate. J. Food Sci. 67, 27642769.

MALLIKARJUNAN, P., CHINNAN, M.S., BALASUBRAMANIAM, V.M.

and PHILIPS, R.D. 1997. Edible coatings for deep-fat frying of starchy

products. Lebensm-Wiss. Technol. 30, 709714.

MCHUGH, T.H., AUJARD, J.F. and KROCHTA, J.M. 1994. Plasticized whey

protein edible lms: Water vapor permeability properties. J. Food Sci. 59,

416419, 423.

MCNEILL, K.L., SANDERS, T.H. and CIVILLE, G.V. 2000. Using focus

groups to develop a quantitative consumer questionnaire for peanut

butter. J. Sensory Studies 15, 163178.

MCQUARRIE, E.F. and MCINTYRE, S.H. 1986. Focus groups and the devel-

opment of new products by technologically driven companies: Some

guidelines. J. Prod. Innovation Manag. 1, 4047.

MEI, Y., ZHAO, Y., YANG, J. and FURR, H.C. 2002. Using edible coating to

enhance nutritional and sensory qualities of baby carrots. J. Food Sci. 67,

19641968.

NISPEROS-CARRIEDO, M.O. 1994. Edible coatings and lms based on

polysaccharides. In Edible Films and Coatings to Improve Food Quality

(J.M. Krochta, E.A. Baldwin and M. Nisperos-Carriedo, eds.) pp. 305

335, Technomic Publishing Co., Lancaster, PA.

ORTOLANI, C., ISPANO, M., SCIBILIA, J. and PASTORELLO, E.A. 2001.

Introducing chemists to food allergy. Allergy 56(Suppl. 67), 58.

PARK, H.J. 1999. Development of advanced edible coatings for fruits. Trends

Food Sci. Technol. 10, 254260.

PRESCOTT, J., YOUNG, O., ONEILL, L., YAU, N.J.N. and STEVENS, R.

2002. Motives for food choice: A comparison of consumers from

Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia and New Zealand. Food Qual. Prefer. 13, 489

495.

365 CONSUMER ATTITUDES ON EDIBLE FILMS AND COATINGS

SCHIFFERSTEIN, J.N.J. and OUDE OPHUIS, P.A.M. 1998. Health-related

determinants of organic food consumption in the Netherlands. Food Qual.

Prefer. 9, 119133.

SHETH, J.N., MITTAL, B. and NEWMAN, B.I. 1999. Customer Behavior:

Consumer Behavior and Beyond, Dryden Press, Orlando, FL.

STEWART, D.W. and SHAMDASANI, P.N. 1991. Focus Groups, Sage Pub-

lications, Newbury Park, CA.

STEWART, B., OLSON, D., GOODY, C., TINSLEY, A., AMOS, R., BETTS,

N., GEORGIOU, C., HOERR, S., IVATURI, R. and VOICHICK, J. 1994.

Converting focus group data on food choices into a quantitative instru-

ment. J. Nutr. Educ. 26, 3436.

VERBEKE, W. and VACKIER, I. 2004. Prole and effects of consumer

involvement in fresh meat. Meat Sci. 67, 159168.

WELLER, C.L., GENNADIOS, A. and SARAIVA, R.A. 1998. Edible bilayer

lms from zein and grain sorghum wax or carnauba wax. Lebensm-Wiss.

Technol. 31, 279285.

366 V.C.-H. WAN, C.M. LEE and S.-Y. LEE

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Tle RC 2.1Document4 pagesTle RC 2.1FoxtheticNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Cactus Cove MenuDocument1 pageCactus Cove MenuadelechapinNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Texas Roadhouse Rolls - Love Bakes Good CakesDocument3 pagesTexas Roadhouse Rolls - Love Bakes Good CakesMelissa OviedoNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: I've Never Heard of That!Document48 pagesUnit 4: I've Never Heard of That!constanza vergaraNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Mulligan's Lunch/Dinner MenuDocument2 pagesMulligan's Lunch/Dinner MenuJamie Lynn MorganNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A2 Test Review 456Document8 pagesA2 Test Review 456Minh CTNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledChami Lee GarciaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Punjab Province (Livestock Census 2006)Document157 pagesPunjab Province (Livestock Census 2006)Asim NajamNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- L1 App CookDocument9 pagesL1 App CookSylvester BooNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Global Warming Personal Solutions For A Healthy PlanetDocument2 pagesGlobal Warming Personal Solutions For A Healthy PlanetAhmedkhebliNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Jimma University: Department of Animal Science Specialization in Animal ProductionDocument14 pagesJimma University: Department of Animal Science Specialization in Animal ProductionGemechis GebisaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Lesson 10Document13 pagesLesson 10armin509No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Focus Group ReportDocument5 pagesFocus Group ReportAngel Diadem ViloriaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Business Plan Final 1Document14 pagesBusiness Plan Final 1Mister RightNo ratings yet

- NutriStop Business PlanDocument6 pagesNutriStop Business Planarcher88No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- ToxicologyDocument9 pagesToxicologyPranaw SinhaNo ratings yet

- Dietary Guidelines: For AmericansDocument4 pagesDietary Guidelines: For AmericansAlbuquerque JournalNo ratings yet

- Understanding Ambient Yoghurt: - Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Ambient Yoghurt: - Challenges and Opportunitieshuong2286No ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Teaching PlanDocument3 pagesTeaching PlanGeralyn KaeNo ratings yet

- Market Survey On Fruit Juices: Moksha Chib 13FET1003Document12 pagesMarket Survey On Fruit Juices: Moksha Chib 13FET1003Aritra SantraNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Chemistry Project Class 12Document12 pagesChemistry Project Class 12mihir khabiyaNo ratings yet

- Sample Event Styling DeckDocument23 pagesSample Event Styling DeckSiargao WeddingsNo ratings yet

- Preparation of Soya Bean Milk and Its Comparison With Natural Milk With Respect To Curd Formation, Effect of Temperature.Document15 pagesPreparation of Soya Bean Milk and Its Comparison With Natural Milk With Respect To Curd Formation, Effect of Temperature.Mayank Singh100% (1)

- PLK NutritionguideDocument3 pagesPLK NutritionguideCesar AlvarezNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Future-Feedlot Enterprise: Business Plan For Sheep-Fattening FarmDocument22 pagesThe Future-Feedlot Enterprise: Business Plan For Sheep-Fattening FarmIsuu JobsNo ratings yet

- Third-Term-Test-2ms by Miss Moussaoui SihemDocument2 pagesThird-Term-Test-2ms by Miss Moussaoui SihemZinaMalek100% (3)

- Lanuza Stem128Document9 pagesLanuza Stem128Bianca RomeroNo ratings yet

- The 25 Healthiest Fruits You Can EatDocument2 pagesThe 25 Healthiest Fruits You Can EatHoonchyi KohNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Osmotic DehydrationDocument13 pagesOsmotic DehydrationChristina Joana GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Jaisalmer Kitchen MenuDocument7 pagesJaisalmer Kitchen MenuSai AmithNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)