Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product Performance

Uploaded by

Maria Goreti VongOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product Performance

Uploaded by

Maria Goreti VongCopyright:

Available Formats

ROLPH E.

ANDERSON*

Four psychological theories ore considered in determining the effects of dis-

confirmed expectations on perceived product performance ond consumer satis-

faction. Results reveal that too great a gap between high consumer expectations

and actual product performance may cause a less favorable evaluation of a

product than a somewhat lower level of disparity.

Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of

Disconfirmed Expectancy on

Perceived Product Performance

CONSUMER DISSATISEACTION

It seems incongruous that consumerism could have

become such a powerful prevailing force when the mar-

keting concept, i.e., "customer satisfaction at a profit,"

has been so highly publicized as a successful business

credo since the early 195O's. To date, most of what has

been written about the consumer movement, its un-

derlying eauses, and the appropriate response for busi-

ness has been based on little more than speculation. To

really understand the underlying reasons for consum-

erism, one must follow Alderson's edict to set up

falsifiable propositions or testable hypotheses concern-

ing the problems, then obtain empirical evidence to sup-

port or refute these hypotheses [1]. Today's consum-

erism is such a complex forceso interrelated with

other ecological, social, political, ethical, economic, and

technological problemsthat, at this stage, it ean be

studied empirically only one step at a time. Probably

the most fundamental question being raised about con-

sumerism is: What are the sources of consumer dissat-

isfaction?

No satisfactory literal definition has yet been devel-

oped for consumer satisfaction or dissatisfaction in the

literature of marketing. The Random House Dictionary

states: "dissatisfaction results from contemplating what

falls short of one's wishes or expectations. . . ." Con-

sumer dissatisfaction, then, might be measured by the

degree of disparity between expeetations and perceived

produet performance.

* Rolph E. Anderson is Associate Professor of B"usiness Man-

agement at Old Dominion University.

There is much conflicting evidence in the journals of

psychology regarding the effects on individuals of dis-

confirmed expectancies, and this critical question for

designing promotional mixes has been virtually ignored

in the marketing literature. Only two experiments (with

conflicting results) have been published to date [4, 19].

There may be significant policy implications for quality

control, price, promotion, and other elements of the

marketing mix depending upon whether consumer ex-

pectations are too higli, produet performances too low,

or promotional messages misplaced, i.e., aimed at gen-

erating an inappropriate level of expectations. Cor-

porate promotional mixes may be ereating unrealistic

expeetations for produets which result in consumer dis-

satisfaction upon purchase and use of the products.

Buskirk and Rothe go so far as to say: "It is this sense

of frustration and bitterness on the part of consumers

who have been promised much and have realized less,

that may properly be called the driving force behind

consumerism" [3, p. 62].

THEORETICAL MODELS

In predicting the effects on product evaluation and

customer satisfaction of disparity between expeetations

and actual or objective product performance, at least

four psychological theories may be considered, namely:

(1) cognitive dissonance (assimilation), (2) contrast,

(3) generalized negativity, and (4) assimilation-contrast.

Dissonance or assimilation theory posits that any dis-

erepaney between expectations and produet perform-

anee will be minimized or assimilated by the consum-

er's adjusting his perception of the produet to be more

consistent (less dissonant) with his expectations.

38

Journal of Marketitig Research,

Vol. X (February 1973}, 38-44

CONSUMER DISSATISFACTION: EFFECT OF DISCONFIRMED EXPECTANCY

39

Contrast theory assumes that the customer will mag-

nify the difference between the product reeeived and the

product expected; i.e., if the objective performance of

the product fails to meet his expectations, the customer

will evaluate the product less favorably than if he had

no prior expectations for it. Contrast is thus the con-

verse of assimilation.

The generalized negativity thesis is that any discrep-

ancy between expectations and reality results in a gen-

eralized negative hedonic state, causing the product to

receive a more unfavorable rating than if it had coin-

cided with expectations. Even if the product's perform-

ance exceeds the customer's expectations, it will be

perceived as less satisfying than its objective perform-

ance would justify.

Finally, the assimilation-contrast approach maintains

that there arc zones or latitudes of acceptance and re-

jection in consumer perceptions. If the disparity be-

tween expectations and product performance is suf-

ficiently small to fall into the consumer's latitude of

acceptance, he will tend to assimilate the difference by

rating the product more in line with expectations than

its objective performance justifies. However, if the dis-

crepancy between expectations and actual product per-

formance is so large that it falls into the zone of rejec-

tion, then a contrast effect comes into play and the

eonsumer magnifies the perceived disparity between the

product and his expectations for it.

Which theory is correct? What is the effect on con-

sumer product perception and satisfaction when ex-

pectancies are disconfirmed? To answer this question,

it is necessary to review these theories in more depth.

Cognitive Dissonance (Assimilation)

An unconfirmed expectancy, according to Festinger's

theory of cognitive dissonance, creates a state of dis-

sonance or "psychological discomfort" because the out-

come contradicts the cotLsumer's original hypothesis

[13]. The theory suggests that an individual has cognitive

elements (or "knowledges") about his past behavior, his

beliefs and attitudes, and his environments [20], Con-

sumers continually receive various kinds of product in-

formation from their own experience, associates, adver-

tisements, and salesmen. These bits of information are

cognitions which consumers like to have consistent with

one another [15]. When an individual receives two ideas

which are psychologically dissonant, he attempts to re-

duce this mental discomfort by changing or distorting

one or both of the cognitions to make them more con-

sonant. The stronger the cognitive dissonance, the more

motivated he is to reduce dissonance by changing the

cognitive element [2].

As applied to marketing, if there is a disparity be-

tween expectations for a product and the objective per-

formance of that product, the consumer is stimulated

to reduce the psychological tension generated by chang-

ing his perception of the product to bring it more into

Fi gure 1

THEORIES OF DISCONFIRMATION OF EXPECTATIONS

line with his expectations. Therefore, if this proposition

is true, the promotional mix for a product should sub-

stantially lead expectations above product performance

to obtain a higher consumer evaluation or perception

of the company's product. This concept, illustrated in

Figure 1 by the dotted line, shows that perceived product

performance is always between objective performance

and expectations, except when all three coincide. Con-

siderable controversy and some disaffection with the

theory of cognitive dissonance have developed in re-

cent years due to the accumulation of an increasing

amount of contradictory evidence [8, 12, 17, 21]. One

major criticism is that the theory assumes that the indi-

vidual, instead of learning from his purchasing mistakes,

actually increases the probability of making them again

through his efforts to reduce post-purchase dissonance

by justification and rationalization of his decisions [9].

Contrast \

Even in the studies supporting assimilation theory,

some individuals tend to shift their attitudes and evalua-

tions away from expectations aroused by communica-

tions if inconsistent with reality [16]. When expectations

are not matched by actual product performance, con-

trast theory presumes that the surprise effect or con-

trast between expectations and outcome will cause the

consumer to exaggerate or magnify the disparity.

Contrast theory would predict consumer product per-

ceptions as shown by the dashed line in Figure 1. This

theory suggests that slight understatement of the prod-

uct's qualities in advertising might lead to higher cus-

tomer satisfaction with the company's product. Of

course, the advertisement could not so understate the

product's qualities that customers bypass it for an-

other brand. Several studies tend support to the possible

success of this promotional strategy flO. 14. 16, 22, 23,

241. One of the two marketing studies reported to date

provided some support for contrast theory albeit find-

ings were divided into support of assimilation theory as

40

JOURNAL OF MARKETING RESEARCH, FEBRUARY 1973

well [5]. In attempting to reconcile the difference be-

tween assimilation theory and contrast theory, Cardozo

introduced another variable, shopping effort, into the

decision process. Specifically, he found that customer

product evaluation or satisfaction is lower when the

product does not measure up to expectations, but satis-

faction rises as effort expended to obtain the product

increases. Unfortunately, Cardozo's results may have

been affected by a methodological error since his ex-

perimental subjects rated the product (ballpoint pens)

based on expectations generated from leafing through

either high (average price was $1.95) or low (average

price was $.39) price product catalogs. Subsequent

evaluations on a scale of 0 to 100 as compared to the

products in the catalog were not comparable since in-

dividual subject rating criteria shifted depending upon

the catalog assigned [4, p. 246]. For example, a rating

of 50 in the high-expectation condition indicated aver-

age quality for a $1.95 pen, but this same rating would

also indicate average quality for a $.39 pen in the low-

exjx^ctation condition.

Generalized Negativity

A classic study of the consequences of unconfirmed

expectations was conducted by Carlsmith and Aronson

[7]. In a test of their hypothesis that any disconfirma-

tion of an expeeted result will be perceived as less

pleasant or less satisfying than if the expectancy had

been confirmed, they asked individuals to taste bitter

and sweet solutions, manipulated their expectations re-

garding the tastes, and measured the ratings under the

various conditions. It was assumed that bitter was an

unpleasant taste and sweet was a pleasant taste for the

majority of subjects. The Carlsmith and Aronson find-

ings seem to suggest opposing theories. When the sweet

solution was expected and the bitter solution tasted, a

disconfirmed expectancy resulted in a rating of more bit-

ter which would support contrast theory. On the other

hand, when the bitter solution was expected but the

sweet solution came up, a disconfirmed expectancy re-

sulted in a rating of less sweet or assimilation toward

the expected taste in support of assimilation theory.

Carlsmith and Aronson explain this apparent confiict by

arguing that any disconfirmed expectancy results in a

hedonically negative state which is generalized to ob-

jects in the environment. Thus, one can make the follow-

ing prediction: If a customer expects a particular per-

formance from a product but a different performance

occurs, he will judge the product to be less pleasant than

if he had no previous expectancy.

The Carlsmith and Aronson explanation implies that

promotional claims aimed at target customers should

seek to create expectations which are consistent with

actual product performance. In Figure 1, the theory of

generalized negativity is depicted by the line of alternat-

ing dots and dashes. Note that only when expectations

and product performance coincide is the consumer's

evaluation of the product as favorable as its objective

performance.

A ssimilation-Contrast

A final theory for consideration in attempting to pre-

dict the effects on consumer satisfaction of disparities

between expectations and objective product perform-

ance is assimilation-contrast. As its name implies, it

combines the theories of assimilation and contrast. Work

by Hovland, Harvey, and Sherif provides support for the

contention that product performance differing only

slightly from one's expectations tends to result in dis-

placement of product perceptions toward expectations

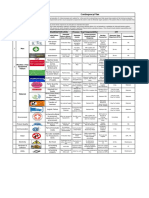

Table 1

PREDICTION MATRIX FOR HYPOTHESES

Treatments^

Ti (with take-measure)

Null hypothesis

Assimilation

Contrast

Generalized negativity

Assimilation-contrast

Ti (without take-measure)

Null hypothesis

Assimilation

Contrast

Generalized negativity

Assimilation-contrast

None

Ca

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Standard

Very low

Cl

Standard

Very low

Very high

Very low

Very high

Standard

Very low

Very high

Very low

Very high

Conditions^

Low

Ca

Standard

Low

High

Low

Low

Standard

Low

High

Low

Low

Accurate

c,

Standard

On

On

On

On

Standard

On

On

On

On

High

c.

Standard

High

Low

Low

High

Standard

High

Low

Low

High

Very high

c

Standard

Very high

Very low

Very low

Very low

Standard

Very high

Very low

Very low

Very low

' Conditions consist of various levels of expectancies generated by product information.

^ Treatments consist of the presence or absence of a "take-measure" in the form of a questionnaire regarding expectancies gen-

erated following receipt ol" product information.

CONSUMER DISSATISFACTION: EFFECT OF DISCONFIRMED EXPECTANCY

41

(assimilation effect), while large variances between one's

expectations and actual product performance tend to

be exaggerated (contrast effect) [16]. The theory as-

sumes that individuals have ranges or latitudes of ac-

ceptance, rejection, and neutrality. Whether assimila-

tion or contrast effects develop is a function of the

relative disparity between expectations and actual prod-

uct performance.

Assimilation-contrast theory suggests that promo-

tional messages should create expectations for the prod-

uct as high as possible without creating a level of dis-

parity between expectations and objective performance

which falls outside the consumer's range of acceptance.

In accord with assimilation-contrast theory, consumer

perceptions of product performance would take the

form of the S-shaped curve in Figure 1.

HYPOTHESES

In order to discover which, if any, of the above out-

lined theories best describes the true relationships be-

tween these important consumer variables, five hypoth-

eses were tested, as follows:

1. Null Hypothesisproduct perceptions are not

significantly different for various levels of expecta-

tions.

2. Assimilationproduct perceptions will vary directly

with the level of expectations.

3. Contrastproduct perceptions will vary inversely

with the level of expectations.

4. Generalized Negativityproduct perceptions will

always be negative when there is disparity between

expectations and actual product performance, and

the degree of negativity will vary directly with the

amount of disparity.

5. Assitnilation-Contrastproduct perceptions will

vary directly with expectations over a range around

actual performance, but above and below this

threshold, product perceptions will vary inversely

with the level of expectations.

METHODOLOGY

A 2 X 6 factorial research design was used to test the

five hypotheses. Manipulation of the independent vari-

able (expectations) was accomplished by randomly as-

signing subjects to one of five different levels of per-

suasive product information, or no product information.

As verified in pretesting, condition one (Ci) substantially

understated the product's features, C2 slightly under-

stated the features, C;^ described the product accurately,

C4 slightly overstated the quality of the product's fea-

tures, and Cfl substantially overstated its features. Sub-

jects (Ss) in Co were given no product information, but

instead they received a communication unrelated to the

experiment. In addition, a "take-measure" in the form

of a self-administered questionnaire was given, after

presentation of product information but before seeing

the product, to half the Ss in each condition to ensure

that expectations were being created in the desired di-

rection and intensity. The basic experimental design

and prediction matrix for the experiment hypotheses

are provided in Table 1.

Evaluations of identical, unmarked ballpoint pens

selling at retail for about $1.00 each were obtained in

group administration from 144 students enrolled in an

undergraduate marketing course. To increase involve-

ment, Ss were told that they could keep the particular

pen randomly assigned them for evaluation, whether it

turned out to be one of the expensive pens or not. Ss

were permitted to inspect and test the product for the

same length of time, then record their reactions on a

modified logarithmic product rating scale anchored in

dollars and cents distributed in small ranges from $.04

to $64.00, as illustrated in Figure 2. (To faciUtate anal-

ysis, these ratings were later converted to integers by

sequentially numbering the rows of the product rating

scale.) Ss rated the ballpoint pen on 15 visual features

and performance characteristics. The unweighted mean

of these ratings by each S constituted the first dependent

variable. The second dependent variable consisted of

an overall rating by Ss on the pen's combined charac-

teristics. This was a weighted mean since each S was

able to assign certain product features more weight

Fi gure 2

PRODUCT RATING SCALE

ON THIS PEN,

EACH OF THESE

CHARACTERISTICS

IS ABOUT LIKE

THE ONES OF PENS

COSTING BETWEEN

Si.04/*

.06

.!

.12

.19

.25

.37

.50

.75

$ 1.00

1.50

2.00

3.00

4.00

.00

e.oo

12.00

16.00

24.00

32.00

46.00

64.00

EXACTLY HOW MUCH DO YOU THINK THIS flALlPOINI PEN IS WCWTH7 J

42

than others in determining his overall evaluation. Lastly,

Ss estimated the ballpoint pen's price to obtain the third

dependent variable.

RESULTS

The mean responses by condition and treatment for

the experiment are presented in Table 2. Manipulation

of the independent variable (product information) cre-

ated expectations in the desired direction with signifi-

cant differences of intensity. Mean scores for the de-

pendent variables (product ratings) show product

perceptions are in the direction of expectations until

manipulation at the "very high" level, which caused a

reversal and downturn in product ratings for all three

measurement variables.

On each dependent variable, Ss gave the product a

more favorable evaluation when it was accurately de-

scribed in C;i than when no product information was

provided in Cn. Duncan's New Multiple Range Test

[11] revealed that there was a significant difference at

the .01 level between mean scores for C3 and Co- Re-

sults of the one-way analysis of variance (treatment

variable collapsed since Ss were not sensitized by the

"take-measure") indicated that Ss responded with sig-

nificant differences in their evaluations or perceptions

of the product depending upon their level of expecta-

tions, as can be seen in Table 3.

Table 2

MEAN RESPONSE BY CONDITION AND TREATMENT

Manipulation

Expectations

Dependent variable"

A

; B

C

Product ratings

Treatment l^-

A

B

C

Treatment 2''

A

B

C

Combined"

A

B

C

Ci

Very

low

2.97

3.25

3.67

6.43

6.58

7.00

6.22

6.58

6.92

6.33

6.58

6.96

G

Low

4.31

4.25

5.42

7.22

7.83

7.92

6.84

7.17

7.92

7.03

7.50

7.92

Co

None

7.24

8.42

7.50

7.39

8.00

8.17

6.96

7.33

8.50

7.17

7.67

8.33

Cs

Accu-

rate

8.54

8.92

9.58

8.56

9.00

9.58

8.94

9.25

9.58

8.75

9.13

9.58

c,

High

11.70

12.42

12.08

9.21

9.75

10.00

10.05

10.50

10.75

9,63

10.13

10.38

Cs

Very

high

15.92

16.67

17.08

9.00

9.25

9.83

8.38

8.67

10.08

8.69

8.96

9.96

Dependent variable A = Product features, B = Combined

characteristics, C = Price.

^ Treatment 1 = Take-measure; Treatment 2 = No take-

measure.

"Treatment variable collapsed.

JOURNAL OF MARKETING RESEARCH, FEBRUARY 1973

Relating Experimental Results to Theoretical Models

Data for each of the three dependent variables were

plotted by each of the six conditions. Inspection of the

plots indicated conformity with assimilation theory un-

til reaching C5, which showed a decline in product rat-

ings for all three dependent variables in accord with the

assimilation-contrast theory of disconfirmation of ex-

pectations.

The tests for linearity in Table 4 showed deviations

from linearity to be highly significant for the relation-

ship between expectations and perceived product per-

formance for each of the dependent variables. Signifi-

cant deviations from linearity discounted both the null

hypothesis and the possibility of assimilation theory de-

scribing the data. The positive slope of the plotted data

ruled out contrast theory which demands a negatively

sloped relationship between expectations and product

perceptions. Finally, the deviation from linearity or

kink in the curve occurred at the wrong point to support

the Carlsmith-Aronson hypothesis of generalized nega-

tivity. Therefore, the data best fit assimilation-contrast

theory, since product ratings were assimilated toward

expectations until the "very high" condition when con-

trast effect began, causing a downturn away from ex-

pectations in evaluations of the product.

CONCLUSIONS

The experiment revealed that there is a point beyond

which consumer will not accept increasing disparity be-

tween product claims and actual performance, at least

for certain relatively simple or easily understood prod-

ucts. When this threshold of rejection is reached, con-

sumers will perceive the product less favorably than at a

slightly lower level of expectations. More complex

products, where there is considerable ambiguity and un-

certainty in making judgments, may yield different re-

sults as consumers may tend to be more dependent on

the information provided them. Olshavsky and Miller

investigated the effects on product evaluations of both

overstatement and understatement of product quality for

a reei-ty[>e tape recorder and found assimilation theory

supported in each case [19].

Product Commitment

Contrast effects did not appear in C,, "very low" ex-

pectations. This result may be partially explained by

"floor effects" which prevented manipulation of expec-

tations far enough below the relatively low cost item (a

dollar ballpoint pen) to cause sufficient surprise or ex-

hilaration upon seeing and trying the product. Due to

insufficient commitment to low-priced products, it sim-

ply may not be possible to obtain contrast effects at

very low expectation levels. Freedman has shown that

personal involvement or commitment to the product is

a determinant of the level of disparity necessary to pro-

duce maximum perceptual change [14]. With strong

CONSUMER DISSATISFACTION; EFFECT OF DISCONFIRMED EXPECTANCY

43

commitment, even a small disparity between expecta-

tions and product performance may fall outside the

consumer's range of acceptance.

The failure of an upturn to occur in Ci at the low

end of the range of expectations is not sufficiently rele-

vant to marketers to merit much discussion since no

advertiser would drastically disparage his product if he

wished to stimulate a high volume of sales. Though re-

peat purchasing rates might be high, once consumers

tried the product, no such negative promotional strategy

would be likely to achieve the desired initial trial rate.

A tnount of Information

Ratings in C3 were consistently higher than ratings

in Co, thus another important conclusion from the ex-

periment is that a more favorable evaluation is obtained

when a product is accurately described than when little

or no product information is provided. This finding sup-

ports Cardozo's suggestion that the mere processing of

information may lead to a more favorable evaluation of

the product, not only because customers have greater

knowledge on which to base evaluation, but also because

the processing of information about products constitutes

a form of commitment to the products [6]. It would

appear that marketers who provide more relevant in-

formation about their products will generate higher

evaluations and customer satisfaction for their products

than those marketers who depend on persuasive mes-

sage content that provides only minimal information.

Of course, the amount of information customers may

willingly process without boredom or confusion no

doubt varies widely among individuals and products.

But, since consumers perceive selectively in some or-

ganized fashion, it is probably better to provide too

much product information than too little. One study

found that when marketers provide insufficient product

information for consumers, they merely encourage or

force consumers to seek information about the product

from other sources, such as friends, associates, inde-

pendent rating organizations, consumer groups, govern-

ment agencies, and competitors [18].

IMPLICATIONS FOR MARKETING

Results of the experiment have important implica-

tions for positioning the level of promotional claims.

Assuming that consumer dissatisfaction is a function of

the disparity between expectations and perceived prod-

uct performance, unrealistic consumer expectations gen-

erated by excessive promotional exaggeration can result

in consumer dissatisfaction. Since consumer expectations

apparently affect satisfaction with a product, the mar-

keter who wishes to understand and favorably influence

customer satisfaction with his ofTcring may be able to do

so by understanding and influencing customer expecta-

tions. That is, if consumer expectations are a function

of promotion, and customer satisfaction is a function of

Table 3

ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE: PRODUCT PERCEPTIONS

(TREATMENT VARIABLE COLLAPSED)

Sources

Product features

Between conditions

Within conditions

Combined characteristics

Between conditions

Within conditions

Price

Between conditions

Within conditions

d.f.

5

138

5

138

5

138

Mean

Squares

38.77

3.85

40.46

4.34

42.28

3.82

F-ratio

10.06^

9.31

n.08

p < .01.

expectations, then satisfaction may be considered a func-

tion of promotion.

Some consumers may have unrealisticaDy high ex-

pectations for product performance even without the

added boost of promotional claims. Distribution of un-

realistic expectancies among consumers may stem partly

from widespread faith in the achievements and possi-

bilities of research and technology, resulting in the feel-

ing that products can and should be made to perform

flawlessly. As history demonstrates, standards and per-

formance expectations for all categories of products

(from automobiles to clothing) tend to steadily rise and

people become increasingly less tolerant of product de-

ficiencies.

Enlightened company executives might profitably re-

assess the often implicit sales-oriented view that the

higher the level of consumer product expectations stim-

ulated by promotion the better because the primary ob-

jective of the promotional mix is to sell the product.

This attitude can be contagious among competing com-

panies. However, the accumulation of consumer dissat-

isfaction may eventually erupt in a demand for more

consumer protection legislation, resulting in a more re-

strictive marketing environment.

EUTURE RESEARCH

As indicated by the Olshavsky and Miller findings, the

applicability of the different theories of expectations

may vary across product classes [19]. More research

needs to be conducted with a variety of products and

services. Disconfirmation of expectations for products

for which consumers make deep personal and financial

commitments may have substantially different effects on

consumer perceptions of performance than less personal,

lower cost, and less ego-related goods. A logical exten-

sion of the present study and previously reported ex-

periments is consideration of time. Does the consumer

become more objective in evaluating products he has

purchased as he gathers information and feedback from

various sources, or does he become more committed to

JOURNAL OF MARKETING RESEARCH, FEBRUARY 1973

Table 4

DEVIATION FROM LINEARITY: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

EXPECTATIONS AND PRODUCT PERCEPTIONS

6.

-. "Customer Satisfaction: Laboratory Study and Mar-

' Sources

1

Product features

Between groups

Linear regression

Deviation from lin-

ear regression

(DJ

Error term (E)

D/E

Combined characteristics

Between groups

Linear regression

Deviation from lin-

ear regression

(D)

Error term (E)

D/E

Price

Between groups

Linear regression

Deviation from lin-

ear regression

(D)

Error term (E)

D/E

d.f.

4

1

3

115

4

1

3

115

4

1

3

115

Sums of

sqtiares

177,19

117.65

59,54

189,75

117.17

72.58

203.58

154.70

48.88

Mean

siitiares

19.85

3.88

24,19

4.56

16.29

3.91

5.12"

5,30-

4.17'

p < .01.

products over time and thus more satisfied with extended

usage? It might also be important to determine if signifi-

cant differences between consumer reactions to expec-

tations-performance disparity can be attributed to psy-

chographic variables.

REFERENCES

1. Alderson, Wroe. Dynamic Marketing Behavior. Homewood,

111.: Riehard D. Irwin, 1965.

2. Brehm, Jack W. and Arthur R. Cohen. Explorations in Cog-

nitive Dissonance. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1962.

3. Buskirk, Richard H. and James T. Rothe. "Consumerism

An Interpretation," Jottrnal of Marketing, 34 (October

1970), 61-5.

4. Cardozo. Richard N. "An Experimental Study of Customer

Effort, Expectation, and Satisfaction," Journal of Marketing

Research, 2 (August 1965), 244-9.

5. . "An Experimental Study of Customer Effort, Ex-

pectation, and Satisfaction," unpublished doctoral disserta-

tiewi. University of Minnesota, 1964.

keting Action," Proceedings. Fall Conference, American

Marketing Association, 1964, 283-9.

7. Carlsmith, J. Merrill and Elliot Aronson. "Some Hedonic

Consequences of the Confirmation and Disconfirmation of

Expectancies," Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,

66(Eebruary 1963), 151-6.

8. Chapanis, Natalia P. and Alphonse Chapanis. "Cognitive

Dissonance: Eive Years Later," Psychological Bulletin, 61

(January 1964), 1-22.

9. Cohen, Joel B. and Marvin E. Goldberg. "The Dissonance

Model in Post-Decision Product Evaluation," Journal of

Marketing Research, 7 (August 1970), 315-21.

10. Diab, Lutfy N. "Some Limitations of Existing Scales in the

Measurement of Social Attitudes," Psychological Reports,

17 (October 1965), 427-30.

11. Duncan, David B. "Multiple Range and Multiple F Tests,"

Biometrics, 11 (March 1955), 1-42.

12. Feldman, Shel, ed. Cognitive Consistency: Motivational

Antecedents and Behavioral Consequences. New York: Aca-

demie Press, 1966.

13. Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. New

York: Harper & Row, 1957.

14. Freedman, Jonathan L. "Involvement, Discrepancy and

Change," Jottrnal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 69

(September 1964), 290-5.

15. HoUoway, Robert J. "An Experiment on Consumer Dis-

sonance,"/ourna/o/Mor^f/i/ig, 31 (January 1967), 39^3.

16. Hovland, Carl L, O. J. Harvey, and Muzafer Sherif. "As-

similation and Contrast Effects in Reactions to Communi-

cation and Attitude Change," Journal of Abnormal and

Social Psychology. 55 (July 1957), 244-52.

17. Insko, Chester A. Theories of Attitude Change. New York:

Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1967.

18. Katona, George and Eva Mueller. "A Study of Purchase

Decisions," in Lincoln Clark, ed.. Consumer Behavior: The

Dynamics of Consumer Reaction, I. New York: New York

University Press, 1955, 74-5.

19. Olshavsky, Richard W. and John A. Miller. "Consumer

Expectations, Product Performance, and Perceived Product

Quality," Journal of Marketing Research, 9 (February

1972). 19-21.

20. Oshikawa, Sadaomi. ' The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance

and Experimental Research," Journal of Marketing Re-

search. 5 (November 1968), 429-30.

21. Rosenberg, Milton I. "When Dissonanee Fails: On Elimi-

nating Evaluation Apprehension from Attitude Measure-

ment," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1

(January 1965), 28-42.

22. Sherif, Muzafer and Carl I. Hovland. Social Jtidginent:

Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Communication and

Attitude Change. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961.

23. Spector, Aaron J. "Expectations, Fulfillment, and Morale,"

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52 (January

1956). 51-6.

24. VVhittaker. James O. "Attitude Change and Communication-

Attitude Discrepancy," Jottrnal of Social Psychology, 65

(February 1965), 141-7.

You might also like

- Summary The Psycholoy of Advertising Fennis & Stroebe Chapter 1Document7 pagesSummary The Psycholoy of Advertising Fennis & Stroebe Chapter 1RianneNo ratings yet

- Coolit SystemsDocument5 pagesCoolit SystemsUsama NaseemNo ratings yet

- SPOT X DevDocument52 pagesSPOT X DevJaoNo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument5 pagesTheoretical FrameworkMa. Janelle Bendanillo100% (2)

- Absolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationFrom EverandAbsolute Value: What Really Influences Customers in the Age of (Nearly) Perfect InformationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorFrom EverandMeasuring Customer Satisfaction: Exploring Customer Satisfaction’s Relationship with Purchase BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Substation Automation HandbookDocument454 pagesSubstation Automation HandbookGiancarloEle100% (6)

- Unit 3 Digital Documentation: Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument7 pagesUnit 3 Digital Documentation: Multiple Choice Questions07tp27652% (21)

- American Marketing AssociationDocument8 pagesAmerican Marketing AssociationDiana YaguanaNo ratings yet

- New Edit Pro Honda SahibQQQDocument69 pagesNew Edit Pro Honda SahibQQQMuhammad IbrahimNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument14 pagesChapterVishnuNadarNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 1Document74 pagesChapter - 1Harry HS100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction TheoryDocument5 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Theorythar tharNo ratings yet

- Theories For ResearchDocument6 pagesTheories For ResearchRissabelle CoscaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGDocument74 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGjassi7nishadNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGDocument74 pagesA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards National Garage Raipur CGjassi7nishadNo ratings yet

- According To Hasemark and AlbinssonDocument6 pagesAccording To Hasemark and AlbinssonAshwinKumarNo ratings yet

- How to Measure Customer SatisfactionDocument9 pagesHow to Measure Customer SatisfactionMubeenNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Customer SatisfactionDocument53 pages1.1 Customer Satisfactionhuneet SinghNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument9 pagesCustomer Satisfaction - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaRashidKhanNo ratings yet

- 05 Project Final HariDocument75 pages05 Project Final HariMichael WellsNo ratings yet

- Chpt4Customersatisfactiontheories PDFDocument38 pagesChpt4Customersatisfactiontheories PDFJenekNo ratings yet

- Customer SatisfactionDocument4 pagesCustomer SatisfactionThat Pahadi GirlNo ratings yet

- 10 PDFDocument13 pages10 PDFVadym PukhalskyiNo ratings yet

- Marketing: Customer Satisfaction Is A Term Frequently Used inDocument7 pagesMarketing: Customer Satisfaction Is A Term Frequently Used inLucky YadavNo ratings yet

- Omkar Bro ProjectDocument50 pagesOmkar Bro ProjectG B Preethi100% (1)

- Shaping Customer Satisfaction Through Subtle CuesDocument17 pagesShaping Customer Satisfaction Through Subtle CuesArief AccountingSASNo ratings yet

- Project On Nokia Customer SatisfactionDocument60 pagesProject On Nokia Customer Satisfactionsalma0430100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction Theories PDFDocument34 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Theories PDFdanookyereNo ratings yet

- Whence Consumer LoyaltyDocument13 pagesWhence Consumer LoyaltySiddhartha SinhaNo ratings yet

- 5629Document20 pages5629Sakshi RavalNo ratings yet

- Defining Consumer SatisfactionDocument28 pagesDefining Consumer Satisfactionibrahim ojonugwaNo ratings yet

- Chpt4 ThConsumer Satisfaction Theories A Critical RevieweoriesDocument35 pagesChpt4 ThConsumer Satisfaction Theories A Critical RevieweoriesJithendar Reddy67% (3)

- Customer Satisfaction TheoryDocument8 pagesCustomer Satisfaction TheoryFibin Haneefa100% (1)

- Defining Customer SatisfactionDocument27 pagesDefining Customer SatisfactionTamil VaananNo ratings yet

- Customer Loyalty Toward An Integrated Conceptual FrameworkDocument15 pagesCustomer Loyalty Toward An Integrated Conceptual Frameworkdeheerp100% (7)

- Sahil Final ProjectDocument24 pagesSahil Final ProjectShanil SalamNo ratings yet

- Emotional or Rational? Determining the Influence of Advertising Appeal on EffectivenessDocument24 pagesEmotional or Rational? Determining the Influence of Advertising Appeal on EffectivenessShazia AllauddinNo ratings yet

- Consumer Sketicism AdvertisingDocument28 pagesConsumer Sketicism AdvertisingAlex RichieNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Marketing - 1998 - Hennig Thurau - The Impact of Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Quality On CustomerDocument28 pagesPsychology and Marketing - 1998 - Hennig Thurau - The Impact of Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Quality On CustomerPrerna SinghNo ratings yet

- New FileDocument54 pagesNew FileSubhash BajajNo ratings yet

- Customersatisfaction TheoriesDocument14 pagesCustomersatisfaction TheoriesMutebi AndrewNo ratings yet

- Chapter I Final 3Document13 pagesChapter I Final 3Catherine Avila IINo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Consumer Complaint BehaviourDocument21 pagesTaxonomy of Consumer Complaint Behaviourgork akNo ratings yet

- Customer SatisfactionDocument5 pagesCustomer SatisfactionAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- 10 - Isac, Rusu 1Document7 pages10 - Isac, Rusu 1Rafel KurniaNo ratings yet

- Dhampur Sugar MillsDocument27 pagesDhampur Sugar MillsSuneel SinghNo ratings yet

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction Must orDocument13 pagesMeasuring Customer Satisfaction Must orcindyNo ratings yet

- Measuring Customer SatisfactionDocument16 pagesMeasuring Customer SatisfactionpiusadrienNo ratings yet

- A Study On Consumer Satisfaction Towards Lux Siddesh N BDocument3 pagesA Study On Consumer Satisfaction Towards Lux Siddesh N BMadhu RakshaNo ratings yet

- Comm Paper2Document7 pagesComm Paper2api-642868572No ratings yet

- Conceptual Review: Customer Satisfaction, A Business Term, Is A Measure of How Products and ServicesDocument6 pagesConceptual Review: Customer Satisfaction, A Business Term, Is A Measure of How Products and ServicesDippali BajajNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Consumer BehaviorDocument11 pagesAn Introduction To Consumer BehaviorKuldeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behavior Model Exam BreakdownDocument14 pagesConsumer Behavior Model Exam BreakdownVignesh VSNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 1 - Group 1Document19 pagesPractical Research 1 - Group 1Mack Jigo DiazNo ratings yet

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction: Expectations, Attributes & LoyaltyDocument13 pagesMeasuring Customer Satisfaction: Expectations, Attributes & LoyaltyGissmoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Advertisement On Brand Loyalty and Consumer Buying BehaviorDocument13 pagesThe Role of Advertisement On Brand Loyalty and Consumer Buying BehaviorAli MalikNo ratings yet

- Impact of Deceptive Advertising On Customer Behavior and Attitude: Literature ViewpointDocument5 pagesImpact of Deceptive Advertising On Customer Behavior and Attitude: Literature ViewpointNoor SalmanNo ratings yet

- 3.project ReportDocument23 pages3.project ReportDnyaneshwarPhadtareNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction As A Predictor of Customer Advocacy and Negative Word of Mouth: A Study of Hotel IndustriesDocument36 pagesCustomer Satisfaction As A Predictor of Customer Advocacy and Negative Word of Mouth: A Study of Hotel IndustriesankitatalrejaNo ratings yet

- Don't Just Relate - Advocate (Review and Analysis of Urban's Book)From EverandDon't Just Relate - Advocate (Review and Analysis of Urban's Book)No ratings yet

- Global Food Politics and Policy SyllabusDocument13 pagesGlobal Food Politics and Policy SyllabusMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Analisis Usaha Kecil Minya KelapaDocument11 pagesAnalisis Usaha Kecil Minya KelapaMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- 10 10 1 SMDocument13 pages10 10 1 SMHadi SopianNo ratings yet

- Receipt PDFDocument1 pageReceipt PDFMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Consumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product PerformanceDocument8 pagesConsumer Dissatisfaction: The Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy On Perceived Product PerformanceMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Session 29Document26 pagesSession 29Dayana AmirNo ratings yet

- Atauro IslandDocument26 pagesAtauro IslandMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Anuciano Tiket Dan InvoiceDocument2 pagesAnuciano Tiket Dan InvoiceMaria Goreti VongNo ratings yet

- Costallocationvideolectureslides 000XADocument12 pagesCostallocationvideolectureslides 000XAWOw Wong100% (1)

- Econometrics IIDocument4 pagesEconometrics IINia Hania SolihatNo ratings yet

- ATC Flight PlanDocument21 pagesATC Flight PlanKabanosNo ratings yet

- Lesson No. 1 - Pipe Sizing HydraulicsDocument4 pagesLesson No. 1 - Pipe Sizing Hydraulicsusaid saifullahNo ratings yet

- The PersonalityDocument7 pagesThe PersonalityMeris dawatiNo ratings yet

- Sims4 App InfoDocument5 pagesSims4 App InfooltisorNo ratings yet

- Gathering Statistical DataDocument8 pagesGathering Statistical DataianNo ratings yet

- Sketch 5351a Lo LCD Key Uno 1107Document14 pagesSketch 5351a Lo LCD Key Uno 1107nobcha aNo ratings yet

- Worksheet Mendel's LawsDocument3 pagesWorksheet Mendel's LawsAkito NikamuraNo ratings yet

- Eugene A. Nida - Theories of TranslationDocument15 pagesEugene A. Nida - Theories of TranslationYohanes Eko Portable100% (2)

- VISAYAS STATE UNIVERSITY Soil Science Lab on Rocks and MineralsDocument5 pagesVISAYAS STATE UNIVERSITY Soil Science Lab on Rocks and MineralsAleah TyNo ratings yet

- Government of India Sponsored Study on Small Industries Potential in Sultanpur DistrictDocument186 pagesGovernment of India Sponsored Study on Small Industries Potential in Sultanpur DistrictNisar Ahmed Ansari100% (1)

- Valve Control System On A Venturi To Control FiO2 A Portable Ventilator With Fuzzy Logic Method Based On MicrocontrollerDocument10 pagesValve Control System On A Venturi To Control FiO2 A Portable Ventilator With Fuzzy Logic Method Based On MicrocontrollerIAES IJAINo ratings yet

- Hot and Cold CorrosionDocument6 pagesHot and Cold CorrosioniceburnerNo ratings yet

- Modern Tips For The Modern Witch (/)Document5 pagesModern Tips For The Modern Witch (/)Rori sNo ratings yet

- OPM - Assignment 2Document12 pagesOPM - Assignment 2Nima IraniNo ratings yet

- Kathryn Stanley ResumeDocument2 pagesKathryn Stanley Resumeapi-503476564No ratings yet

- Time May Not Exist - Tim Folger in DiscoverDocument3 pagesTime May Not Exist - Tim Folger in DiscoverTrevor Allen100% (5)

- Ib Tok 2014 Unit PlanDocument10 pagesIb Tok 2014 Unit Planapi-273471349No ratings yet

- StuffIt Deluxe Users GuideDocument100 pagesStuffIt Deluxe Users Guidesergio vieiraNo ratings yet

- Contingency PlanDocument1 pageContingency PlanPramod Bodne100% (3)

- Fireclass: FC503 & FC506Document16 pagesFireclass: FC503 & FC506Mersal AliraqiNo ratings yet

- Microorganisms Friend or Foe Part-5Document28 pagesMicroorganisms Friend or Foe Part-5rajesh duaNo ratings yet

- Structural Crack Identification in Railway Prestressed Concrete Sleepers Using Dynamic Mode ShapesDocument3 pagesStructural Crack Identification in Railway Prestressed Concrete Sleepers Using Dynamic Mode ShapesNii DmNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Sir MarcosDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Sir MarcosJhon AgustinNo ratings yet

- Ch15 Differential Momentum BalanceDocument20 pagesCh15 Differential Momentum Balance89kkNo ratings yet