Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How To Write A Musical by John Kenrick PDF

Uploaded by

Ivesnelson100%(4)100% found this document useful (4 votes)

1K views16 pagesWriters, composers and lyricists rarely try to explain how they create. No one can give you a method or road map to creating a musical, says john kenrick. Kenrick: "what works for any one of them may not work for anyone else"

Original Description:

Original Title

How To Write a Musical by John Kenrick.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWriters, composers and lyricists rarely try to explain how they create. No one can give you a method or road map to creating a musical, says john kenrick. Kenrick: "what works for any one of them may not work for anyone else"

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(4)100% found this document useful (4 votes)

1K views16 pagesHow To Write A Musical by John Kenrick PDF

Uploaded by

IvesnelsonWriters, composers and lyricists rarely try to explain how they create. No one can give you a method or road map to creating a musical, says john kenrick. Kenrick: "what works for any one of them may not work for anyone else"

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 16

How To Write a Musical by John Kenrick

Copyright 2000 (Revised 2009)

The Bad News

Compelling Need

What's It About?

Things to Keep in Mind

Nine Rules

Why You Should NOT Write Musicals

Why You SHOULD Write Musicals

The Bad News

Have you noticed that almost all the books on how to write

songs, lyrics or musicals are written by

teachers, not working professionals? Real writers,

composers and lyricists rarely try to explain how they

create, because the creative process is unique what

works for any one of them may not work for anyone else.

Teachers can offer theory and analysis of form, but that

doesn't shed any light on the act of artistic creation.

So let's settle this one right up front no one can tell you

how to create! A seasoned pro may offer pointers, and

people with a wide knowledge of the genre can tell you

what forms and approaches have worked up to now, but

the bad news is that no one can give you a method or road

map to creating a musical.

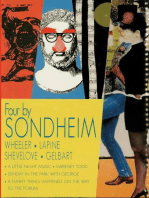

To see how intensely personal the creative process is, let's

compare the approaches used by four great lyricist-

librettists

William S. Gilbert wrote all his drafts in expensive

leather-bound journals, saving every idea and

deleted line for possible use in the future. These

meticulous notebooks are still preserved after

more than a century, providing a goldmine for

researchers. Gilbert always wrote a complete

version of the book and lyrics for a new comic

opera before submitting anything to composer

Arthur Sullivan -- then, as Sullivan composed,

Gilbert would make revisions as needed.

Rehearsals usually led to more revisions, and the

material might be edited or even re-written or

based on the reactions of audiences.

When lyricist Larry Hart worked with composer

Richard Rodgers, they would talk through a

potential project (frequently collaborating with a

co-librettist, such as Herb Fields), deciding where

the songs would go, which characters would sing

them, and what each song could do to develop

the characters & plot. Then Hart usually waited

for Rodgers to compose the melodies. Hart would

listen to a new tune once or twice, then dash off

the lyrics with amazing speed, scrawling on any

available scrap of paper -- sometimes just filling

the spare space in a magazine ad. The libretto

would be rewritten through the final weeks of

rehearsal, and was subject to major revisions right

up to its opening night on Broadway.

Oscar Hammerstein II also worked with Rodgers,

but in their collaborations the book and lyrics

were usually written first. After the two men

discussed the dramatic intention of a potential

song, Hammerstein retreated to his Pennsylvania

farm, where he curled into a chair and labored

over every lyric for days or weeks at a time, neatly

organizing his ideas on legal pads, then typing

them out himself. While the first drafts of scripts

were finished long before the first rehearsal, they

were subject to extensive revision during pre-

Broadway tryouts.

Alan Jay Lerner's habit of flying halfway around

the world to avoid writing commitments

frequently left his collaborators in a frustrating

state of limbo, sometimes for months on end.

Lerner was so crippled by nerves that he wore

white cotton gloves to avoid chewing his fingers

raw while working on a new project. The books

and lyrics for his musicals were usually completed

during high-pressure tryouts, adding tremendous

tension to the process. (After creating My Fair

Lady, Lerner had a recurring nightmare about a

group of friends coming into a hotel room to ask

what he had written after several days locked

inside. Surrounded by mounds of crumpled pages,

Lerner dreamt he would hold up a sheet and read,

'Loverly, loverly, loverly, loverly' whereupon his

friends would cart him off to an asylum.)

Each of these men had their share of hits and flops, so it is

impossible to define any method as right or wrong. Each

writer, composer or collaborative team must figure out

(usually by trial and error) what works best for them. The

point is that they go through the hell of creating no

matter how uncomfortable or terrifying that hell might be.

Compelling Need

If you are going to write a musical, you are setting out to

offer an audience a story. What makes a musical

compelling, what commands audience interest? Music? Oh

please! A musical must have characters who need or want

something desperately, and that need comes up against an

equally powerful obstacle. The resulting conflict forces

these characters to give their all, risk everything and this

is why audiences feel compelled to see how these stories

turn out. All successful book musicals involve characters

who have something or someone they are willing to put

everything on the line for. Some examples

Rent offers a small army of characters who are

willing to face miserable poverty in pursuit of

their creative dreams.

In Guys and Dolls, each major character is

eventually willing to radically redefine their life in

order to marry the person they love.

Sweeney Todd will stop at nothing to kill those

who sent him to prison on a trumped-up charge.

Audiences are fascinated to see Todd's need for

revenge consume everything he once loved.

Singin' In the Rain has movie star Don Lockwood

simultaneously trying to save his screen career

and win the love of Kathy Seldin, the girl he loves.

In Wicked, gifted witch Elphaba is willing to

abandon her dreams of respectable success in

order to stand up for what she believes to be

right.

How do you know if your story is compelling? Well, how

compelled are you to tell it? Do you care deeply about it,

so deeply that you must tell this story or die? Believe it or

not, that's a very good sign. If you are writing because you

think you have a hot topic others will go for, please double

check your motives. It is impossible to judge in advance

what critics and audiences will applaud for -- all the

greatest talents have miscalculated at one time or another.

Your best bet is always to go with material you care about

deeply, a story and characters that you believe in.

Moss Hart once told Alan Jay Lerner that nobody knows

the secret to writing a hit musical . . .but the secret to

writing a flop is "to say yes when you mean no."

Those are the truest words ever spoken about musicals! If

every fiber of your being says "Yes!" to a potential project,

it improves the odds that others will care about it too.

What's It Really About?

When Jerome Robbins agreed to direct the original Fiddler

On The Roof, he asked the authors a crucial question:

"What is your show about?" They answered that it was

about a Russian Jewish milkman and his family, and

Robbins told them to think again. He wanted to know what

the show was really about at its emotional core what was

the main internal force that would drive the action and

touch audiences both intellectually and emotionally?

(Many academics call this core the premise of a story.)

Eventually, the authors realized that the show was really

about the importance of family and tradition, and about

what happens when a way of life faces extinction. This not

only gave them the idea for a magnificent opening number

("Tradition") it also gave what could have been a very

parochial show irresistible universal appeal. This is why the

fable of Tevya the Russian-Jewish milkman has moved

audiences all over the world.

When writing a musical, you must eventually figure out

your premise, what your show is really about at its core.

Then you must make sure that every element of your

material serves that premise every character, every

scene, every line, every song. Anything that does not serve

the premise is extraneous and should be cut. That may

sound ruthless, but it is the secret to building a really good

show.

A good premise gives your musical project wide ranging (if

not universal) appeal. This does not mean you should limit

yourself to common characters facing common challenges

far from it! For example, Sweeney Todd tells the story of

a Victorian barber out to kill the vile men who stole his

beloved wife and sent him off to rot in prison on false

charges. But at its core, the show is really about the

terrifying cost of revenge, how past resentment can cost

everything our past, our present and even our future.

This premise makes Sweeney's story the audience's story.

Today, even a revue can have a premise. When Pig's

Fly was a set of hilarious songs and skits built around one

gay man's obsession with succeeding in the theatre --

despite everyone warning that he would succeed only

"when pig's fly." But the show's premise was that the more

outrageous or "over the top" a dream is, the more it is

worth pursuing. That theme resonated with gays and

straights alike, and When Pig's Fly enjoyed a long and

profitable off-Broadway run.

Things to Keep in Mind

Consider these key questions posed by the original

producer of 1776 and Pippin --

"The greatest question musical dramatists must answer is:

does the story I am telling sing? Is the subject sufficiently

off the ground to compel the Ened emotion of bursting

into song? Will a song add a deeper understanding of

character or situation?"

- Stuart Ostrow, A Producer's Broadway Journey (Praeger:

Westport, CT. 1999), p. 96.

If all songwriters and librettists answered those questions

diligently, audiences would be spared innumerable hours

of boredom. Dissect the worst musical you have ever seen

(I am serious about this; pick the one you hate the most),

and odds are you will find that the story does not really

"sing," does not call for the Ened emotion of characters

bursting into song.

Beyond that basic issue, there are other pointers worth

remembering. In the course of my production career on

and off Broadway, I have worked with dozens of

songwriters and librettists, from gifted unknowns to Tony

and Academy Award winners. Based on that experience,

there are several things I would recommend if you want to

write musicals

See as many musicals as you can, on stage or

screen.

Study the musicals you like and figure out what

makes them tick.

Study the musicals you don't like and figure out

what prevents them from ticking. You can

sometimes learn far more by studying a flop than

a flawless hit -- at the very least, look at flops as

practical lessons in what not to do!

Since musicals are a collaborative art form, do

your best to find collaborators you can work with

comfortably.

Find or invent a story idea that gets you so excited

you can spend five or more years of your life

working on it with no promise (or even a

reasonable hope) of it earning you a penny.

Structure your life in such a way that it leaves you

daily time to write and/or compose.

Be sure this life structure provides a way for you

to keep the bills paid.

Work only on projects you are passionate about

never take on a musical based solely on its

commercial possibilities. This year's "hot" idea

often proves to be next year's embarrassment.

Make sure your work has a genuine sense of

humor. Too many new writers and composers

tend to concoct "serious" musicals

that bore audiences.

Don't waste time being afraid of messing up

every creative talent in history has written a

clunker. Better yet, every great musical had

started as a clunky first draft. It takes determined

effort and revision to bring out the best in any

project. If you treat every project you work on as

a learning experience, I'll make you a promise;

you will find that even a "failed" scene or song

can be a very creative place.

Eight Rules For Writing Musicals

While no one can tell you how to write a musical, (is there

an echo in here?), there are a few basic rules that may help

aspiring authors and composers along the road to their

first opening night. But don't take my word on any of them

-- prove them yourself. They will apply to any great musical

currently in existence. The first four rules apply to good

writing of any kind

1. Show, Don't Tell This is job one for all writers, now

and forever. Don't tell us what your characters are let

their actions show us! Drama is expressed in action, not

description. No one has to tell us that Seymour in Little

Shop of Horrors is a gullible nerd; his every action screams

it out. Peggy Sawyer never has to declare that she is a

naive newcomer to 42nd Street's hard-edged world of

show business -- her wide-eyed behavior makes that clear

from her first scene.

There is another aspect to "show, don't tell." Since theater

and film are visual as well as literary mediums, musicals

are not limited to words and music. Many a great musicals

uses the power of visual images to communicate key

information. (Plays are called "shows," no?) The waiters

in Hello Dolly never have to tell us that they love Dolly

their visible reaction to her presence shows it all. And no

one in My Fair Lady has to announce when Liza Doolittle

becomes a lady her wordless, elegant descent down the

stairs before leaving for the Embassy Ball shows that the

transformation has occurred.

2. Cut everything that is not essential Some call this the

"kill your darlings" rule. Every character, song, word and

gesture has to serve a clear dramatic purpose. If not, the

whole structure of your show can suffer. If something does

not develop character, establish setting or advance the

plot, you must cut it -- even if it is a moment that you love.

The next time you see a musical that seems to be losing

steam, odds are that the writers did not have the heart to

cut non-essential material. Never show your audiences

such a lack of respect ruthlessly cut everything that does

not serve a clear and vital purpose to your premise.

3. Know the basics of good storytelling Musicals are just

another form of telling stories, an art humans have been

practicing since the invention of speech. Can you tell me

what your show is really about (the premise), and define

the essential dramatic purpose of each character? And

does every scene offer a character with deep desire

confronting a powerful obstacle?

Learning the art of storytelling does not mean getting a

masters degree good news, friend: the basic tools of

storytelling are already in you. Reading a few good books

can get you thinking in the right direction. For starters,

try Jerry Cleaver's Immediate Fiction: A Complete Writing

Course (NY: St. Martin's Griffin, 2002). It will open your

eyes to the unseen elements that make a great story

absorbing, and a great story is the best starting point for

any book musical. If you need to go deeper, read Robert

Olen Butler's From Where You Dream: The Process of

Writing Fiction (NY: Grove Press, 2005). Both of these

books are ground breaking, and both can save you years of

misguided effort.

On the specific subject of writing original musicals, Making

Musicals (NY: Limelight Editions, 1998) by Tom Jones is

the only book on the subject written by a bona fide creator

of musical hits (The Fantasticks, etc.). He offers no magic

formulas, but his gentle wisdom can enrich anyone facing

the creative process.

4. Your first duty in writing a musical is to tell a good

story in a fresh, entertaining way NEVER to teach or

preach. If you make one or more intelligent points along

the way, that's fantastic, but it won't matter much if your

audience has lost interest, or simply stayed away. Dance a

Little Closer condemned war and homophobia, and closed

on its opening night. On the other

hand, Hairspray skewered bigotry and ran for years. And

while some critics dismiss The Sound of Music as fluff, it

has probably done more harm to the ongoing threat of

Nazism than all the World War II documentaries ever

made.

If you always put the story and characters first, you won't

have to hit anyone over the head with a lesson or

message. A well-told story lives in the memory long after

any sermon or lecture. I beg you: if you want to preach,

build a pulpit. When you are really lucky, the one who will

learn something from your writing is you.

Now, some rules that apply specifically to the musical form

5. Find the Song Posts - Song placement in a musical is not

arbitrary! Irving Berlin said that he evaluated potential

projects by looking for the "posts" points in the story

that demand a song. Call these key moments whatever you

like, but they are the places where characters have some

emotional justification for singing. Think about your

favorite musical; the songs all have something to say,

expressing important feelings or concerns of the

characters. Joy, confusion, heartbreak, love, rage at the

points or posts where these life-defining feelings break

through, characters can sing.

6. Open With a Kick-Ass Song Every now and then, a

successful musical (My Fair Lady, The King and I) opens

with a few pages of dialogue before the opening number,

but these are the exceptions. In most cases, the quickest

way to touch a musical theatre audience is through song.

An effective number or musical scene sets the tone for the

show to come and also allows swift plot exposition &

character development. By the end of the opening

number, audiences should know where the story is set,

what sort of people are in it, and what the basic tone of

the show (comic, satiric, serious, etc.) will be. This is why

the opening number ought to be one of the strongest in

the score. A great opening number reassures audiences

that there more good things to come. Think ofRagtime's

title song, which handily introduces audiences to an army

of characters and the distant era they lived in! Other

examples: Oklahoma ("Oh, What a Beautiful

Morning"), Les Miserables ("At the End of the

Day"), Urinetown ("Too Much Exposition"),

and Hairspray ("Good Morning, Baltimore").

7. Book, Score and Staging MUST Speak as One In

contemporary musical theater, the score, libretto and

staging (both direction and choreography) share the job of

storytelling. This results in frequent passages of sung

dialogue, as well as scenes where characters move

seamlessly between spoken word, dance and song. Think

of the hilarious "Keep It Gay" in The Producers, the

achingly beautiful "If I Loved You" bench scene inCarousel,

or the powerful dances ignited by the songs in Moving

Out the dialogue, lyrics and staging form a single fabric.

The trick is to keep the content smooth and varied. A hint

if your libretto goes on for pages and pages between

isolated musical numbers, something is probably wrong.

And if your score has a stretch of ballad after ballad, give

your audiences a break and vary the tone. In other words,

lighten up!

8. Songs Are Not Enough When you turn an existing

story into a musical, you need a fresh vision. Just adding

songs won't give you an effective musical. You have to tell

the story with a fresh dose of energy, of re-

inspiration. Annie took the characters from a classic comic

strip, added some new faces and placed them all in an

entirely new story. Some of the best moments in My Fair

Lady did not come from Shaw's Pygmalion -- including the

crux of the pivotal "Rain in Spain" scene. When you add

songs, you must also re-ignite the material at hand.

9. Sing It or Say It; NEVER Both Rouben Mamoulian, the

original director of Porgy & Bess, Oklahoma & Carousel put

it this way: "It's the basic law that the music and dancing

must extend the dialogue. If you say the same thing in a

song you already have said in the speeches, it's without

point. . . a song must lift the spoken scene to greater S

than it was before, or the song must be cut no matter how

beautiful is the melody. The song must not merely repeat

in musical terms what has already been put across by the

dialogue and actions." (Maurice Zoltow, NY Times,

1/29/1950, "Mamoulian Directs a Musical," section 2, p.1)

Why You SHOULD NOT Write A Musical

Yes, I mean you. Working in the professional theatre can

be hell yes, hell. hat is why several wise people have

been credited with saying that the worst thing they could

wish on Hitler was that he "be stuck out of town working

on a new musical!"

Can you stand the merciless judgment of producers,

potential backers, fellow creators, press critics, anonymous

internet chatroom snipers, and (gulp!) paying audiences?

Can you handle years (and I mean years) of anonymous,

unpaid struggle? Are you ready to work your butt off eight

hours or more at a demanding day job and then somehow

find the energy to write on the side? Can you handle the

fact that most people will have no idea who you are or

what you do even if you win a Tony or an Oscar? Finally,

can you handle doing all this for no more than 2% of a

show's profits? (That's the percentage the

authors share under the present standard contract, so if

you collaborate, you only get a piece of that!) This is not a

career for the dilettante -- or for the feint of heart:

"This is a tough business, a cruel business. The

competition, especially in New York and especially in the

musical theatre, is fierce. Not without reason is there the

saying: "It is not enough that I succeed, my friends have

also to fail." There is a tendency after you have been in the

rat race for a while to open the Times and slowly relish the

roasting given to some competitor, possibly even to some

friend."

- Tom Jones, Making Musicals: An Informal Introduction

to the World of Musical Theatre (New York: Limelight

Editions, 1998), pp. 188.

Why You SHOULD Write A Musical

You should write musicals only if there is no possible way

for you not to. If all the negatives cannot dissuade you, go

for it! You might be crazy enough to succeed in this snake

pit. Just be sure that you always have a solid means of

paying your bills and recharging your spirits. And while

talent and luck are valuable to any aspiring composer,

lyricist or librettist, there are three things that matter even

more patience, determination, and guts. One of the

worlds greatest musical comediennes said the following

about acting in an interview, but it applies to writers and

composers too

"I'll give you a tip it's risk. Once you're willing to risk

everything, you can accomplish anything."

- Patricia Routledge, Tony-winning actress

There are as many ways to write a musical as there are

musicals. If you do decide to venture forth into this

daunting field, know that my best wishes and the best

wishes of millions of ticket-buying theatre lovers hungering

for something new and wonderful will go with you.

You might also like

- Mixing A Musical Parte 1Document43 pagesMixing A Musical Parte 1ALEX XXII100% (1)

- The Business of Broadway: An Insider's Guide to Working, Producing, and Investing in the World's Greatest Theatre CommunityFrom EverandThe Business of Broadway: An Insider's Guide to Working, Producing, and Investing in the World's Greatest Theatre CommunityNo ratings yet

- Cabaret Secrets: How to Create Your Own Show, Travel the World and Get Paid to Do What You LoveFrom EverandCabaret Secrets: How to Create Your Own Show, Travel the World and Get Paid to Do What You LoveNo ratings yet

- Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to WickedFrom EverandDefying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to WickedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Broadway General Manager: Demystifying the Most Important and Least Understood Role in Show BusinessFrom EverandBroadway General Manager: Demystifying the Most Important and Least Understood Role in Show BusinessNo ratings yet

- Elements of A MusicalDocument36 pagesElements of A MusicalKevin Gilmond100% (3)

- Broadway Musicals by YearDocument9 pagesBroadway Musicals by YearJennifer100% (3)

- The Commercial Theater Institute Guide to Producing Plays and MusicalsFrom EverandThe Commercial Theater Institute Guide to Producing Plays and MusicalsNo ratings yet

- Book BuildingDocument5 pagesBook BuildingPatrick BrettNo ratings yet

- Musical Theater StructureDocument12 pagesMusical Theater StructureChristopher Ridgley100% (1)

- Broadway Musicals (Art Ebook) PDFDocument368 pagesBroadway Musicals (Art Ebook) PDFBogdan ZamfirNo ratings yet

- Becoming Stephen SondheimDocument402 pagesBecoming Stephen SondheimDavid100% (2)

- Notes on the Writing of A Gentleman's Guide to Love and MurderFrom EverandNotes on the Writing of A Gentleman's Guide to Love and MurderNo ratings yet

- Studies in Musical Theatre: Volume: 2 - Issue 1Document124 pagesStudies in Musical Theatre: Volume: 2 - Issue 1Intellect Books100% (13)

- Maury Yeston-The Inspiration & Writing Process For Death Takes A HolidayDocument12 pagesMaury Yeston-The Inspiration & Writing Process For Death Takes A HolidayMusical Theatre Guild0% (1)

- Intro to Musical TheatreDocument10 pagesIntro to Musical TheatresunshinesunshineNo ratings yet

- Ethan Mordden Anything Goes A History of American Musical Theatre Oxford University Press 2013 PDFDocument359 pagesEthan Mordden Anything Goes A History of American Musical Theatre Oxford University Press 2013 PDFJuran Jones100% (3)

- Aida Musical Broadway ShowDocument6 pagesAida Musical Broadway ShowKelsey MullerNo ratings yet

- Hadestown Lyrics GuideDocument6 pagesHadestown Lyrics GuideTristan TkNyarlathotep Jusola-Sanders50% (2)

- Musical Misfires: Three Decades of Broadway Musical HeartbreakFrom EverandMusical Misfires: Three Decades of Broadway Musical HeartbreakNo ratings yet

- Violet - OBCR - Digital BookletDocument47 pagesViolet - OBCR - Digital BookletKaiyi Chen100% (1)

- OOTI StudyGuide PDFDocument22 pagesOOTI StudyGuide PDFJustin LongoNo ratings yet

- Musical Theater. A History PDFDocument425 pagesMusical Theater. A History PDFLucas Millán100% (4)

- Musical Theatre RepertoireDocument2 pagesMusical Theatre RepertoireAndrew MorleyNo ratings yet

- Writing For TheaterDocument8 pagesWriting For TheaterDorian BasteNo ratings yet

- A Chorus Line FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Broadway's Singular SensationFrom EverandA Chorus Line FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Broadway's Singular SensationNo ratings yet

- Drowsy Chaperone (Center Theatre Group)Document13 pagesDrowsy Chaperone (Center Theatre Group)Hilly McChefNo ratings yet

- Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created "Sunday in the Park with George"From EverandPutting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created "Sunday in the Park with George"No ratings yet

- The Book of Broadway Musical Debates, Disputes, and DisagreementsFrom EverandThe Book of Broadway Musical Debates, Disputes, and DisagreementsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Musicality in TheatreDocument320 pagesMusicality in TheatreOlya Petrakova100% (6)

- Performing in Musicals - Novak, Elaine AdamsDocument324 pagesPerforming in Musicals - Novak, Elaine AdamsMIRNA JULIETA100% (2)

- Excavating The Song 2013Document135 pagesExcavating The Song 2013BenNorthrup100% (2)

- Schwartz On MusicalsDocument26 pagesSchwartz On MusicalsFrancois OlivierNo ratings yet

- Creating Musical Theatre Ebook-1Document305 pagesCreating Musical Theatre Ebook-1Júlia GarciaNo ratings yet

- Trends in Musical Theatre VoiceDocument4 pagesTrends in Musical Theatre VoiceBrandon Weber100% (3)

- Stephen Sondheim and His Filmic InfluencesDocument89 pagesStephen Sondheim and His Filmic InfluencesJamesRuth67% (3)

- Broadway GlossaryDocument6 pagesBroadway GlossaryPhoebe JacksonNo ratings yet

- Stanislavskis System in Musical Theatre Acting Training Anomalies of Acting SongDocument13 pagesStanislavskis System in Musical Theatre Acting Training Anomalies of Acting SongMitchell Holland100% (2)

- Studies in Musical Theatre 2.1Document122 pagesStudies in Musical Theatre 2.1Intellect BooksNo ratings yet

- In Heights StudyguideDocument56 pagesIn Heights StudyguidePattyCowNo ratings yet

- Song Analysis SheetDocument5 pagesSong Analysis SheetBenjamin Troy WaltonNo ratings yet

- 2013 Education Resources Sunday in The Park With George Theatre Studies ResourceDocument28 pages2013 Education Resources Sunday in The Park With George Theatre Studies ResourceAndrew Kendall100% (3)

- Chicago Character DescriptionsDocument2 pagesChicago Character DescriptionsOliver A-SNo ratings yet

- Musical Theatre Choreography: Reflections of My Artistic Process for Staging MusicalsFrom EverandMusical Theatre Choreography: Reflections of My Artistic Process for Staging MusicalsNo ratings yet

- In Heights PDFDocument168 pagesIn Heights PDFTiciana De LelloNo ratings yet

- Acting The Song - Performance Skills For The Musical TheatreDocument7,575 pagesActing The Song - Performance Skills For The Musical TheatreRafael Reis0% (1)

- Musical Theatre ChartDocument3 pagesMusical Theatre ChartAnonymous 4mUxIKmzNo ratings yet

- Running Theaters, Second Edition: Best Practices for Leaders and ManagersFrom EverandRunning Theaters, Second Edition: Best Practices for Leaders and ManagersNo ratings yet

- Acting in Musical TheaterDocument2 pagesActing in Musical TheaterSofía GabrielaNo ratings yet

- Memphis Study GuideDocument34 pagesMemphis Study GuideMack Digital100% (4)

- A Harmonic Analysis of The Baker and His Wife in Stephen Sondheim's Musical: Into The WoodsDocument16 pagesA Harmonic Analysis of The Baker and His Wife in Stephen Sondheim's Musical: Into The WoodsColin Sanders100% (1)

- Ancient Greek Cynicism philosophy schoolDocument4 pagesAncient Greek Cynicism philosophy schoolGlerommie CastroNo ratings yet

- Topic 51 - Oscar Wilde and Bernard ShawDocument21 pagesTopic 51 - Oscar Wilde and Bernard Shawvioleta2ruanoNo ratings yet

- Untitled Corvus Corax Project Issue #1Document7 pagesUntitled Corvus Corax Project Issue #1weirdbirdpalNo ratings yet

- Ancient Trails - So It BeginsDocument24 pagesAncient Trails - So It BeginsTrashDogNo ratings yet

- Cleric SpellsDocument3 pagesCleric SpellsAchilleas PetroutzakosNo ratings yet

- Tsukahara Jushien 塚原渋柿園 Murakami Namiroku 村上浪六Document20 pagesTsukahara Jushien 塚原渋柿園 Murakami Namiroku 村上浪六Nguyễn Thừa NhoNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Humanism in ShakespeareDocument3 pagesRenaissance Humanism in Shakespearetaniya100% (1)

- Derrida Filosofía CircumfessiónDocument36 pagesDerrida Filosofía CircumfessiónVerena SylviaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 1 - MonaDocument5 pagesLesson Plan 1 - Monaapi-302287248No ratings yet

- English 178x The American Novel 2013 SyllabusDocument3 pagesEnglish 178x The American Novel 2013 SyllabusLucy ChenNo ratings yet

- "Creative Non-Fiction": Week 9-10Document13 pages"Creative Non-Fiction": Week 9-10Hearty Fajagutana RiveraNo ratings yet

- Alden Dauril From Colony To Nation Essays On The Independence of Brazil by Russell Wood PDFDocument3 pagesAlden Dauril From Colony To Nation Essays On The Independence of Brazil by Russell Wood PDFDermeval MarinsNo ratings yet

- Gayatri Mantram SPDocument17 pagesGayatri Mantram SPvaidyanathan100% (1)

- VidyamanyarIna Advaita Khandana VyakhyaDocument22 pagesVidyamanyarIna Advaita Khandana Vyakhyarammohan thirupasurNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Toni Morrison's The Bluest EyeDocument2 pagesAn Analysis of Toni Morrison's The Bluest EyeIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Carol Ann Duffy - OMPLISTT Guided Annotation - Education For Leisure - , - Head of EnglishDocument2 pagesCarol Ann Duffy - OMPLISTT Guided Annotation - Education For Leisure - , - Head of EnglishTanishq Bindra100% (2)

- Netbook of ClassesDocument147 pagesNetbook of ClassesTalithan100% (4)

- Sweeney Todd Study Guide: The Demon Barber of Fleet StreetDocument17 pagesSweeney Todd Study Guide: The Demon Barber of Fleet StreetIlzebrottelNo ratings yet

- Model QP PG S2 Ind LittDocument3 pagesModel QP PG S2 Ind Littanoop00krishnanNo ratings yet

- Roberto Arlt's Aguafuerte Genre and Its Modern InterpretationsDocument8 pagesRoberto Arlt's Aguafuerte Genre and Its Modern InterpretationsJustin LokeNo ratings yet

- Sun Rising by Sheeren Shahid....Document4 pagesSun Rising by Sheeren Shahid....Zahra KhanNo ratings yet

- The Persian Miniature - On Art and AestheticsDocument7 pagesThe Persian Miniature - On Art and AestheticsMatei-Alexandru MocanuNo ratings yet

- A Low Art-The Female VoiceDocument15 pagesA Low Art-The Female VoiceAmihan Comendador Grande100% (1)

- When A Man Loves A Woman - DevduttDocument1 pageWhen A Man Loves A Woman - DevduttAnik KarmakarNo ratings yet

- Poranjo OkiojDocument35 pagesPoranjo OkiojDragana TintorNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Devices PRINTDocument8 pagesStylistic Devices PRINTIveta KaritoneNo ratings yet

- Book Review PDFDocument23 pagesBook Review PDFDraque TorresNo ratings yet

- Jane Austen Research PaperDocument8 pagesJane Austen Research PaperMystiqueRain100% (2)

- English 7 Q1 Mod 2Document14 pagesEnglish 7 Q1 Mod 2JeanreyGasoLazagaNo ratings yet

- Worship of Ashtarte FinishedDocument10 pagesWorship of Ashtarte FinishedRoss MarshallNo ratings yet