Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Impact of PsyCap

Uploaded by

proffsyedCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Impact of PsyCap

Uploaded by

proffsyedCopyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 87: 253259, 2012

Copyright C Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.609844

The Impact of Business School Students

Psychological Capital on Academic Performance

Brett Carl Luthans

Missouri Western State University, St. Joseph, Missouri, USA

Kyle William Luthans and Susan M. Jensen

University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, Nebraska, USA

Psychological capital (PsyCap) consisting of the psychological resources of hope, efcacy,

resiliency, and optimism has been empirically demonstrated in the published literature to

be related to manager and employee positive organizational outcomes and to be open to

development. However, to date, little attention has been devoted to the impact of this positive

core construct on important student-related outcomes. This study tests the relationship between

business students PsyCap and their academic performance (grade point average [GPA]). The

results indicate not only the predictive relationship between PsyCap and GPA, but also have

important implications for training of PsyCap for business student development, retention, and

success.

Keywords: academic performance, PsyCap, PsyCap training, psychological capital, student

development

Great organizational leaders such as Andy Grove and Bill

Gates are widely quoted as saying that the most important

assets in their company walk out the door every night. In other

words, they understand that it is their human capital that rep-

resents a distinctive competency that has created value and

separated Intel and Microsoft from their competitors. A core

goal of business schools is to help build this human capital.

They aspire to deliver educated, mature graduates who have

acquired the knowledge, skills, and abilities to ultimately be

successful in the workplace and help their employers distin-

guish themselves from the competition. Traditional methods

at universities to help meet this goal have focused on the

implementation of generic learning skills courses to improve

insufcient performance, or identifying and building up stu-

dents technical and intellectual deciencies. A too often

overlooked approach would be to also focus on and build

on the strengths and positive psychological resources of stu-

dents.

Correspondence should be addressed to Brett Carl Luthans, Missouri

Western State University, Steven L. Craig School of Business, 4525 Downs

Drive, St. Joseph, MO 64507, USA. E-mail: luthans@yahoo.com

The purpose of this study is to explore the role that the

recently recognized psychological resources represented by

what has been identied as psychological capital may have

on business students academic performance. This psycho-

logical capital has emerged from the positive psychology

movement (see Luthans, Youssef, and Avolios [2007] book

that gives the background and theory of psychological cap-

ital) and to date has received considerable attention in the

elds of organizational behavior and human resource man-

agement, but not business education. However, of particular

relevance to business students and ultimately all college grad-

uates entering the job market is that the environment todays

organizations operate in is very challengingdynamic, ul-

tracompetitive, and full of uncertainty.

We propose one way to help engage students and prepare

themto compete and be effective in this kind of newparadigm

environment is through the development of the psychological

capital resources of hope, efcacy, resiliency, and optimism

(sometimes referred to as the HERO within). Together, these

four capacities make up psychological capital, or simply Psy-

Cap (Luthans, Luthans, & Luthans, 2004; Luthans, Youssef,

et al., 2007). Recent research has clearly demonstrated that

PsyCap can be validly measured and is a higher order

core construct that predicts outcomes better than the four

254 B. C. LUTHANS ET AL.

constructs that make it up (Luthans, Avolio, Avey, & Nor-

man, 2007). In addition, a great amount of research indicates

PsyCap is strongly related to desired manager and employee

attitudes, behaviors, and performance (see the recent meta-

analysis by Avey, Reichart, Luthans, & Mhatre, 2011). More

specically, PsyCap has been shown to positively impact

performance at individual and group levels of analyses (e.g.,

Gooty, Gavin, Johnson, Frazier, & Snow, 2009; Luthans,

Avolio, et al., 2007; Walumbwa, Luthans, Avey, &Oke, 2011;

Walumbwa, Peterson, Avolio, & Hartnell, 2010). Moreover,

PsyCap has been demonstrated to provide additive value to

more established measures of employees positive behaviors,

such as organizational citizenship (Walumbwa et al., 2011),

in addition to demographic and more traditional individual

difference constructs such as personality characteristics, core

self-evaluations, and person-organization and person-job t

(Avey, Luthans, & Youssef, 2010).

However, to date there has been no empirical evidence as-

sessing the impact that the PsyCap core construct may have

on student academic performance. Thus, this exploratory

study was conducted to help answer this important research

question.

FOUNDATION FOR POSITIVITY AND PSYCAP

About a decade ago, the positive psychology movement

emerged as a reaction to the preoccupation that psychology

has traditionally had with the pathological, predominantly

negative aspects of human functioning and behavior. Well

known research psychologist and former American Psycho-

logical Association President Martin Seligman and some of

his colleagues believed that too much attention in their eld

was being focused on what was wrong with people and not

enough attention was being directed toward the positive qual-

ities and traits of individuals, or what was right with people.

Thus, the goal of the positive psychology movement is to use

scientic methodology to analyze and promote factors that

focus on health and vitality, make peoples lives better and to

build on the strengths of people rather than being preoccu-

pied with their weaknesses. The focus is on optimal human

functioning, as opposed to pathological human functioning

(Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

Drawing from this positive psychology movement,

Luthans (2002a, 2002b) called for research demonstrating

the effectiveness and applicability of positive psychologi-

cal capacities in the workplace. The term positive organiza-

tional behavior (POB) was coined by Luthans (2002b) and

dened as the study and application of positively oriented

human resource strengths and psychological capacities that

can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for

performance improvement in todays workplace (p. 59). He

identied specic inclusion criteria to distinguish POB and

its constructs from the popular self-help or even traditional

positively oriented organizational behavior constructs. The

following unique, scientic criteria must be met: (a) based

on theory and research; (b) use of reliable and valid measures;

(c) be state-like (as opposed to the more xed trait-like, such

as personality characteristics) and thus open to development;

and (d) have an impact on performance (Luthans, 2002a;

Luthans, Avolio, et al., 2007).

Derived from the positive psychology movement (Selig-

man & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000) and the subsequent POB,

PsyCap was identied as going beyond traditional economic

capital (what you have), human capital (what you know),

and social capital (who you know) and consists of who you

are and what you can become (Luthans et al., 2004). Al-

though there are many construct candidates that can be drawn

from positive psychology to operationalize this PsyCap, the

ones that were determined to best meet the aforementioned

inclusionary criteria include hope, efcacy, resiliency, and

optimism and as a core construct is dened as,

. . . an individuals positive psychological state of develop-

ment characterized by: (1) having condence (self efcacy)

to take on and put in the necessary effort to succeed at chal-

lenging tasks; (2) making a positive attribution (optimism)

about succeeding now and in the future; (3) persevering

toward the goals, and when necessary, redirecting paths

to goals (hope) in order to succeed; and (4) when beset

by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back

and even beyond (resilience) to attain success. (Luthans,

Youssef, et al., 2007, p. 3)

PSYCAP AND STUDENT ACADEMIC

PERFORMANCE

There are previous research studies which have looked at

the relationship between the various psychological con-

structs that make up PsyCap individually (i.e., hope, ef-

cacy, resilience, or optimism) or sometimes two of them on

the impact of student academic performance, as predom-

inantly measured by grade accomplishment. For example,

the psychological construct of efcacy derived from Ban-

duras (1997) social cognitive theory and dened for appli-

cation to performance as ones conviction about his or her

abilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources or

courses of action needed to successfully execute a specic

task within a given context (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998,

p. 66) was shown to be a strong predictor of rst-year col-

lege student academic performance (Chemers, Hu, & Garcia

2001). Also, in a meta-analysis by Valentine, DuBois, and

Cooper (2004), efcacy was shown to be a strong predictor of

academic success. The psychological construct of optimism,

which is dened as the attributions an individual makes and

the explanatory style an individual uses in response to situ-

ations and events (Seligman, 1998) has been linked to aca-

demic performance as well. For example, studies have shown

that students with more optimistic outlooks signicantly

THE IMPACT OF PSYCAP ON STUDENT PERFORMANCE 255

outperform those with pessimistic outlooks in the classroom

(e.g., Ruthig, Perry, Hall, &Hladkyi, 2004; Solberg, Evans, &

Swgerstrom, 2009; Valentine et al., 2004). Hope, a third psy-

chological resource in the PsyCap core construct, is dened

as a positive motivational state based on an interactively

derived sense of successful (a) agency (willpower) and (b)

pathways (waypower) (Snyder et al., 1991, p. 287). Stud-

ies in educational settings have consistently shown hope to

be predictive of academic performance (e.g., Curry, Snyder,

Cook, Ruby, & Rehm, 1997; Snyder et al., 2002). The nal

psychological variable that makes up PsyCap, resilience, is

dened as a persons ability to bounce back or rebound when

faced with disappointing outcomes, failures, or even positive

changes and events (Luthans, 2002b). Research studies in ed-

ucational settings have shown that students with higher levels

of resilience have stronger academic performance (Martin &

Marsh, 2008).

Because PsyCap has clearly been shown to have a positive

impact on employee performance (Avey et al., 2011; Luthans,

Avolio, et al., 2007) as well as the individual components

with academic performance, our study hypothesis was that

business students PsyCap would be related to their academic

performance as measured by their overall grade point average

(GPA). After presenting the methods and results, we discuss

implications for developing student PsyCap.

METHODS AND RESULTS

Undergraduate students (N =95) enrolledinbusiness courses

at a medium-sized Midwestern university completed a sur-

vey that measured their level of PsyCap in relation to their

academic performance and demographics. Students were in-

formed that the goal of the survey was to better understand

the relationship between an individuals intrinsic capacities

and performance at school. It was emphasized that partici-

pation was voluntary and condential and responses would

only be reported in the aggregate. Students were also in-

formed that the survey information would be analyzed with

GPAs obtained from student transcripts. The widely recog-

nized Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24; for the

entire instrument, see Luthans, Youssef, et al., 2007; for the

validity analysis, see Luthans, Avolio, et al., 2007) was orig-

inally developed and tested for employees in the workplace

and adapted for this study to college students. These adapted

items were derived from a panel of experts (including the

original researchers on the PCQ). The instrument consists

of six items adapted from each of the following scales: (a)

hope (Snyder et al., 1996), (b) resilience (Wagnild & Young,

1993), (c) optimism (Scheier & Carver, 1985), and (d) ef-

cacy (Parker, 1998). Sample items from each of the sub-

scales included There are lots of ways around any problem

concerning my schoolwork (hope); I usually manage dif-

culties one way or another concerning my schoolwork

(resilience); I always look on the bright side of things re-

garding my schoolwork (optimism); and I feel condent

setting targets/goals for my schoolwork (efcacy).

For this study, the Cronbachs alpha reliability was an ac-

ceptable .90. In addition to this adapted academic PsyCap

measure, the survey also gathered demographic information

regarding gender, age, year in school (e.g., freshman, sopho-

more), and major area of study (e.g., accounting, nance,

management, marketing). Survey respondents also reported

whether they were part- or full-time students, the average

number of hours devoted each week to schoolwork, and the

average number of hours worked at a job each week.

The study sample was about evenly split between female

(52%) and male students, who were predominantly Cau-

casian (84%), full-time students (93%) between the ages of

19 and 24 years (85%) who worked while attending school

(75%). The study sample also included freshmen through

seniors from a variety of elds of study, with the largest rep-

resentation from management (36%) and accounting (10%)

majors.

As hypothesized, a signicant and positive relationship

(r = .281, p < .01) was found between the students level of

PsyCap and their ofcial GPA (see Table 1). Use of stepwise

regression, with GPA as the dependent variable, showed that

PsyCap emerged as the rst variable to enter the nal model,

explaining nearly 7% of the variance (adjusted R

2

= .069,

p < .01). The second variable, average number of hours per

week devoted to schoolwork, raised the adjusted R

2

to .123,

increasing the explained variance by approximately 5%. The

nal variable to enter the model, a students year in school,

provided an additional 5% in explained variance. All other

variables (including gender, age, major, full- or part-time

status, and weekly hours worked at a job) were excluded

from the nal model (see Table 2). As shown in Table 3, a

1-point increase in school PsyCap related to a 0.008 increase

in GPA.

DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The purpose of this exploratory study was to examine

the relationship between the school-related PsyCap of

undergraduate business school students and their academic

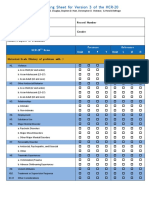

TABLE 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of

Study Variables

Variable M SD 1 2 3

Grade point average 3.00 0.52

Academic PsyCap 110.84 15.28 .281

Average hours/week: School work 14.01 10.76 .279

.108

Average hours/week: Working at job 20.58 14.58 .060 .233 .040

Note. PsyCap = psychological capital.

p = .01.

256 B. C. LUTHANS ET AL.

TABLE 2

Stepwise Regression Model Summary (Dependent

Variable: Grade Point Average)

Model R R

2

Adjusted R

2

F df1 df2 p

Predictors: Academic PsyCap .281 .079 .069 7.964 1 93 .006

Predictors: Academic

PsyCap; average

hours/week: School work

.376 .141 .123 6.700 1 93 .011

Predictors: Academic

PsyCap; average

hours/week: School work;

year in school

.448 .201 .175 6.795 1 91 .011

Note. PsyCap = psychological capital.

performance. Results from a stepwise regression analysis

indicated that students self-reported PsyCap signicantly

correlated with the GPA noted on their ofcial transcript.

These ndings conrmed the predicted relationship and pro-

vide support for the idea that business school students could

benet from the integration PsyCap development activities

within their curriculum. In particular, a series of focused mi-

crotraining interventions could be implemented to enhance

the levels of school-related PsyCap among business students

throughout their academic programs. This development pro-

cess would provide business students with additional tools

they need for overcoming barriers to academic success such

as increasing workschool demands and stress. In addition,

the development of PsyCap among business school students

could potentially become a source of competitive advantage

for future career success. The following provides specic

guidelines for business education programs to proactively

develop the positive PsyCap of their students.

Student Development of PsyCap

As indicated, a key feature of PsyCap is that it is state-

like and open to development through instructional programs

(Luthans, Youssef, et al., 2007). Specically, Luthans, Avey,

Avolio, Norman, and Combs (2006) developed a PsyCap In-

tervention (PCI) training model that has been successfully

implemented in a variety of contexts. For example, Luthans,

TABLE 3

Table of Coefcients (Dependent Variable: Grade

Point Average)

Unstandardized coefcients

Model B SE t p

Constant 1.874 0.358 5.230 .000

Academic PsyCap 0.008 0.003 2.528 .013

Average hours/week:

School work

0.012 0.005 2.652 .009

Year in school 0.348 0.133 2.607 .011

Avey, and Patera (2008) were able to demonstrate a signi-

cant and positive increase in the PsyCap of working adults,

representing a cross-section of industries, who received a

2-hr online training intervention. Using a pretestposttest

control group experimental design, the randomly assigned

treatment group (n =187) that received the PCI experienced

a signicant increase in PsyCap. However, the randomly as-

signed control group (n = 177), which received a different

but relevant intervention in the area of group dynamics and

decision making, did not show a signicant change in Psy-

Cap levels. In other words, this study demonstrated that the

PsyCap training caused the participants PsyCap to increase,

and importantly, could be delivered online.

More recently, Luthans, Avey, Avolio, and Peterson

(2010) demonstrated the ability to develop PsyCap in a study

of undergraduate business students and in a second study

of practicing business managers. Using a controlled experi-

mental design in the rst study, the researchers were able to

demonstrate a signicant difference between the PsyCap lev-

els of undergraduate business school students who received

the PCI training (n = 153) and the randomly assigned stu-

dents in the control group (n = 89) who did not receive the

PCI and did not show an increase in their PsyCap. In the

second study, a heterogeneous group of managers (n = 80)

sampled across a wide variety of organizations received the

PCI. Results indicated that those managers who underwent

the training had signicantly higher levels of PsyCap (Time

1 M = 4.79, Time 2 M = 4.93); t = 2.99, p < .01, following

the training intervention. In addition, both self-rated perfor-

mance (Time 1 M = 7.43, Time 2 M = 8.41), t = 9.14, p <

.01, and manager-rated performance (Time 1 M=7.66, Time

2 M = 8.20), t = 2.34, p < .05, signicantly increased pre-

and posttraining intervention. In sum, this previous research

indicates that the PsyCap training not only increased the par-

ticipants level of PsyCap, but also caused their performance

to improve as well.

These studies clearly demonstrate that PsyCap can be de-

veloped with short training interventions. The PCI model

utilized in these studies focused on developing the four psy-

chological resources of hope, optimism, efcacycondence,

and resiliency. Previous research demonstrated discriminant

validity among the four constructs and when combined to-

gether, they produced a synergistic effect in relation to per-

formance that is better than each of the individual resources

by themselves (Luthans, Avolio, et al., 2007). Each of these

four, when combined into PsyCap, can be readily adapted for

development of students PsyCap.

Drawing on the theoretical and clinical guidelines out-

lined by Snyder (2000), hope is developed in the PCI through

goal design, pathway generation, and strategies for overcom-

ing obstacles. For example, to enhance their levels of hope,

students would be asked to identify personally valuable aca-

demic goals that are measurable (e.g., receive a 3.5 GPA

next semester). Next, they would be asked to generate mul-

tiple pathways to reach the goal and to identify the various

THE IMPACT OF PSYCAP ON STUDENT PERFORMANCE 257

resources required to pursue each pathway. After examining

the various routes to reach each goal, the unrealistic ones

would be discarded and a smaller number of realistic path-

ways identied.

Also targeted for student development in the PCI would be

the three major recognized aspects of resiliency attributed to

the work of Masten (2001). These include asset factors, risk

factors, and inuence processes. The most effective develop-

ment strategies tend to be based on enhancing assets (e.g.,

networking through student and professional organizations)

and avoiding risky, potentially adverse events (e.g., working

long, strenuous hours in a part-time job).

Stemming from the work of Seligman (1998), the PCI

model also offers a relevant framework for developing re-

alistic optimism of students. This approach would ask the

student to reect, diagnose, and identify self-defeating be-

liefs when faced by adversity such as the breakup of a long

dating relationship. Next, they would be asked to reect and

evaluate the accuracy of their beliefs about this event. Finally,

if their beliefs are discounted or questioned, they would be

replaced with more realistic, constructive, and accurate be-

liefs.

The last, and arguably best, psychological resource tar-

geted for student development in the PCI model would be ef-

cacy or condence. Bandura (1997) noted that self-efcacy

beliefs are acquired and modied through four routes. These

include mastery experiences, vicarious learning, social per-

suasion, and emotional or physiological arousal. The PCI

described by Luthans et al. (2006) was designed to allow

participants to experience and model success related to their

personal goals. Similar techniques could be utilized to de-

velop efcacy within business students and incorporated into

a larger PsyCap development program. Specic examples of

how these development techniques could be operationalized

for the development of efcacy in business students include

the following.

Mastery experiences. When individuals successfully

accomplish a challenging task, they are generally more con-

dent in their abilities to accomplish the task again. These per-

formance attainments can be a potent source of efcacy be-

liefs because they provide direct credible information about

past success. Given these ndings, one pedagogical rec-

ommendation would be to ensure that instructors teaching

business classes proceeded from simple to complex. Pro-

viding guided mastery experiences would help to build ef-

cacy early in the process. Another implication would be to

set high expectations and challenges for business students.

Bandura (1999) indicated that mastery experiences attained

through perseverant effort and ability to learn build a strong

perception of efcacy. On the other hand, condence built

from successes that came easily will not be characterized

by much perseverance when difculties arise. Still another

recommendation would be to integrate experiential learning

opportunities for students to experience success throughout

the curriculum. Research suggests that learning complex top-

ics is facilitated by incorporating active learning techniques

such as case studies, collaborative projects, or simulation ex-

ercises (Goorha & Mohan, 2009). Using these various types

of teaching methods would provide opportunities for addi-

tional mastery experiences for students to further develop

their self-efcacy related to core business concepts.

Vicarious learning or modeling. Bandura (1999)

noted that if individuals observe relevant others succeed, they

will have increased efcacy in their own ability to succeed.

The impact of such modeling is dependent on how similar

the individual sees him or herself related to the role model

who successfully completed the task. Conversely, observing

the failure of others instills doubts about an individuals own

ability to master similar activities. Applied to the develop-

ment of efcacy within business students, the increased use

of peer tutoring and study groups would be benecial. Cre-

ating this cooperative classroom style would help to develop

efcacy by providing vicarious learning experiences and also

by using role models who would closely resemble those ob-

serving and lead to the conclusion that if they can do it, I

can do it too.

Social persuasion. The importance of providing a pos-

itive learning environment and feedback on progress is well

established. Students beliefs in their condence can be

strengthened by respected, competent others providing pos-

itive feedback and words of encouragement. On the other

hand, negative remarks, condescending attitudes, and reject-

ing nonverbal cues can have a disabling and deating impact

on an individuals condence. This is not to say that posi-

tive feedback should be fake or given at every opportunity.

In fact, positive psychologist Barbara Fredricksons (2009)

research found optimal performance is obtained from a ra-

tio of three positives to one negative comment or interaction.

Thus, guidelines would include giving sincere, objective, and

developmental positive feedback the vast majority of time to

strengthen efcacy and promote a positive learning experi-

ence.

Physical and psychological arousal. A nal source

of efcacy is an individuals physical and emotional state

of well-being. Briey stated, if people feel overly anxious

or physically tired, their efcacy is likely to be diminished.

Although this source of efcacy is probably the least pow-

erful, it still has applications for helping business students

to overcome their fears and hesitancy. For example, students

who feel pressure and anxiety due to test taking need to be

reassured that their physical or psychological symptoms are

task related (e.g., test anxiety) and not the result of some

personal inadequacy (e.g., lack of ability). By the same to-

ken, research has indicated to avoid potential future esteem

issues, when students do well they should be told, you must

have worked hard on this rather than you must be smart

(see Dweck, 2006).

258 B. C. LUTHANS ET AL.

As indicated in the introductory comments, PsyCap is

state-like and can be changed and developed within indi-

viduals (Luthans, Avey, et al., 2010; Luthans, Avolio, et al.,

2007). The PCI offered by Luthans and colleagues provides a

specic framework for enhancing PsyCap levels with specic

applications relevant to business students. Consistent with the

guidelines provided previously, the various dimensions and

overall PsyCap can be enhanced in specic, relatively short

programs or through the widespread integration of develop-

ment strategies across the entire business curriculum.

CONCLUSION

Considerable research has linked the psychological resources

of hope, resiliency, efcacycondence, and optimism to the

academic performance of college students. When combined

together, these resources create a synergistic effect and form

a higher order construct known as positive PsyCap. Results

from this exploratory study were the rst to demonstrate a

signicant relationship between the PsyCap of college busi-

ness students and their academic performance. Based on

these ndings, it is suggested that further research should

be conducted, using controlled experimentation, to isolate

the measurable impact of PsyCap development on positive

academic outcomes. The initial results from this study can

also serve as a catalyst for collegiate schools of business

to investigate ways to incorporate PsyCap development into

their programs through relatively short interventions or by

comprehensive integration across course design, pedagogy,

and curricula. These development programs could be imple-

mented on a widespread basis or specically targeted for

at-risk students (e.g., rst generation college students, stu-

dents from disadvantaged backgrounds, students with low

entrance exam scores, students with learning disabilities). It

is hoped that PsyCap development could help individuals

overcome obstacles to academic achievement (e.g., stress,

burnout, at-risk factors, resistance to change) and serve as a

competitive advantage for business students competing in a

tough market for placement and for success in their future

careers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Missouri Western State University

Foundation and the Logan Fund as well as the University of

Nebraska Foundation and the Kelly Fund for support of this

research.

REFERENCES

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. M. (2010). The additive value of

positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors.

Journal of Management, 36, 430452.

Avey, J. B., Reichart, R., Luthans, F., & Mhatre, K. (2011). Meta-analysis

of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes,

behaviors and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly,

22, 127152.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efcacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY:

Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin &

O. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd ed., pp. 154225). New

York, NY: Guilford Press.

Chemers, M., Hu, L., & Garcia, B. (2001). Academic self-efcacy and rst-

year college student performance and adjustment. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 93, 5564.

Curry, L. A., Snyder, C. R., Cook, D. L., Ruby, B. C., & Rehm, M. (1997).

Role of hope in academic and sport achievement. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 73, 12571267.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York,

NY: Random House.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2009). Positivity. New York, NY: Crown.

Goorha, P., & Mohan, V. (2009). Understanding learning preferences in

the business school curriculum. Journal of Education for Business, 85,

145150.

Gooty, J., Gavin, M., Johnson, P. D., Frazier, M. L., &Snow, D. B. (2009). In

the eyes of the beholder: Transformational leadership, positive psycholog-

ical capital, and performance. Journal of Leadership and Organizational

Studies, 15, 353367.

Luthans, F. (2002a). The need for and meaning of positive organizational

behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695706.

Luthans, F. (2002b). Positive organizational behavior: Developing and man-

aging psychological strengths. Academy of Management Executive, 16,

5772.

Luthans, F., Avey, J., Avolio, B., Norman, S., & Combs, G. (2006). Psy-

chological capital development: toward a micro-intervention. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 27, 387393.

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., & Peterson, S. J. (2010). The develop-

ment and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital.

Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21, 4167.

Luthans, F., Avey, J., & Patera, J. (2008). Experimental analysis

of a web-based training intervention to develop psychological cap-

ital. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7, 209

221.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M.

(2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship

with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541

572.

Luthans, F., Luthans, K., & Luthans, B. C. (2004). Positive psychological

capital: Going beyond human and social capital. Business Horizons, 47,

4550.

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2007). Psychological capi-

tal: Developing the human competitive edge. Oxford, England: Oxford

University Press.

Martin, A., & Marsh, H. (2008). Academic buoyancy: Towards an under-

standing of students everyday academic resilience. Journal of School

Psychology, 46, 5383.

Masten, A. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes and development.

American Psychologist, 56, 227239.

Parker, S. (1998). Enhancing role-breadth self efcacy: The roles of job

enrichment and other organizational interventions. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 83, 835852.

Ruthig, J. C., Perry, R. P., Hall, N. C., & Hladkyj, S. (2004). Optimism and

attributional retraining: Longitudinal effects on academic achievement,

test anxiety, and voluntary course withdrawal in college students. Journal

of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 709730.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: As-

sessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health

Psychology, 4, 219247.

THE IMPACT OF PSYCAP ON STUDENT PERFORMANCE 259

Seligman, M. E. P. (1998). Learned optimism. NewYork, NY: Pocket Books.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology.

American Psychologist, 55, 514.

Snyder, C. R. (2000). Handbook of hope. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M.,

Sigmon, S. T., . . . Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development

and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570585.

Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S., Ybasco, F., Borders, T., Babyak, M., &Higgins,

R. (1996). Development and validation of the state hope scale. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 321335.

Snyder, C. R., Shorey, H. S., Cheavens, J., Pulvers, K. M., Adams III, V. H.,

& Wiklund, C. (2002). Hope and academic success in college. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 94, 820826.

Solberg, N. L., Evans, D. R., & Swgerstrom, S. C. (2009). Optimism and

college retention: Mediation by motivation, performance, and adjustment.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 18871912.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efcacy and work-related

performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240

261.

Valentine, J. C., DuBois, D. L., & Cooper, H. (2004). The relation between

self-beliefs and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review. Educa-

tional Psychologist, 39, 111133.

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric

evaluation of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1,

165178.

Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Oke, A. (2011). Authentically

leading groups: The mediating role of positivity and trust. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 32, 424.

Walumbwa, F. O., Peterson, S. J., Avolio, B. J., & Hartnell, C. A. (2010). An

investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological

capital, service climate, and job performance. Personnel Psychology, 63,

937963.

Copyright of Journal of Education for Business is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not

be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Transformational and Transactional Leadership in Mental Health and Substance Abuse OrganizationsFrom EverandTransformational and Transactional Leadership in Mental Health and Substance Abuse OrganizationsNo ratings yet

- Psychological Capital (PsyCap) - PramodDocument10 pagesPsychological Capital (PsyCap) - PramodPramod KumarNo ratings yet

- MAKING WELLBEING PRACTICAL: AN EFFECTIVE GUIDE TO HELPING SCHOOLS THRIVEFrom EverandMAKING WELLBEING PRACTICAL: AN EFFECTIVE GUIDE TO HELPING SCHOOLS THRIVENo ratings yet

- Fred LuthansDocument1 pageFred LuthansUsman NiaziNo ratings yet

- Luthans (2017) - Capital PsicológicoDocument30 pagesLuthans (2017) - Capital PsicológicoVinciusNo ratings yet

- Leadership Styles and Companies’ Success in Innovation and Job Satisfaction: A Correlational StudyFrom EverandLeadership Styles and Companies’ Success in Innovation and Job Satisfaction: A Correlational StudyNo ratings yet

- Chap007 - Psy Cap - LuthansDocument32 pagesChap007 - Psy Cap - LuthansPavas SinghalNo ratings yet

- The Handbook of Life-Span Development, Volume 1: Cognition, Biology, and MethodsFrom EverandThe Handbook of Life-Span Development, Volume 1: Cognition, Biology, and MethodsNo ratings yet

- EmpatiaDocument21 pagesEmpatiarominaDnNo ratings yet

- Virga Et Al 2009 PRU - UWESDocument17 pagesVirga Et Al 2009 PRU - UWESCarmen GrapaNo ratings yet

- Effective Health and Wellbeing Programs ReportDocument68 pagesEffective Health and Wellbeing Programs ReportKim Hong OngNo ratings yet

- Towards A Deeper Understanding of Hope and LeadershipDocument13 pagesTowards A Deeper Understanding of Hope and LeadershiptomorNo ratings yet

- Effects of Stress On Organizational OutcomesDocument28 pagesEffects of Stress On Organizational Outcomesramish88No ratings yet

- Recruiting and Selecting Leaders For InnovationDocument7 pagesRecruiting and Selecting Leaders For InnovationPattyNo ratings yet

- JDQ Scale PDFDocument34 pagesJDQ Scale PDFTeguh Lesmana100% (1)

- Podsakoff (2009)Document20 pagesPodsakoff (2009)revolutionbreezNo ratings yet

- Huppert & So 2013 Flourishing Across EuropeDocument28 pagesHuppert & So 2013 Flourishing Across EuropePaulo LuísNo ratings yet

- Book Review: IIMB Management Review (2012) 24, 116e117Document2 pagesBook Review: IIMB Management Review (2012) 24, 116e117Neol SeanNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Work Environment, Work Discipline and Work Motivation On Performance of Employees in The Secretariat Regional People's Representative Assembly West Sumatra ProvinceDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Work Environment, Work Discipline and Work Motivation On Performance of Employees in The Secretariat Regional People's Representative Assembly West Sumatra ProvinceAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Diener 2012Document8 pagesDiener 2012Gildardo Bautista HernándezNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence - An OverviewDocument5 pagesEmotional Intelligence - An Overviewpnganga100% (1)

- Chapter 5 Situational ApproachDocument15 pagesChapter 5 Situational ApproachAugustinus WidiprihartonoNo ratings yet

- 115-Article Text-394-1-10-20191020 PDFDocument11 pages115-Article Text-394-1-10-20191020 PDFDumitrita MunteanuNo ratings yet

- Resilience Building in StudentsDocument15 pagesResilience Building in StudentsRiana dityaNo ratings yet

- On Stress and Coping Mechanisms - SelyeDocument22 pagesOn Stress and Coping Mechanisms - SelyebioletimNo ratings yet

- Hope Therapy PDFDocument18 pagesHope Therapy PDFalexNo ratings yet

- Happiness and Well-Being at Work - A Special Issue IntroductionDocument3 pagesHappiness and Well-Being at Work - A Special Issue IntroductionAileen Gissel BustosNo ratings yet

- A Revision of Freud S Theory of The Biological Origin of The Oedipus ComplexDocument28 pagesA Revision of Freud S Theory of The Biological Origin of The Oedipus ComplexSilvia R. AcostaNo ratings yet

- A Personality Trait-Based Interactionist Model of Job PerformanceDocument18 pagesA Personality Trait-Based Interactionist Model of Job PerformanceAlvina AhmedNo ratings yet

- Mood and Performance Anxiety in HS Basketball Players PDFDocument15 pagesMood and Performance Anxiety in HS Basketball Players PDFmarcferrNo ratings yet

- The Science of Emotional Intelligence - AspDocument6 pagesThe Science of Emotional Intelligence - AspDDiego HHernandezNo ratings yet

- Combating Compassion Fatigue and Burnout in Cancer CareDocument12 pagesCombating Compassion Fatigue and Burnout in Cancer CareFlorin TudoseNo ratings yet

- The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of The ArtDocument20 pagesThe Job Demands-Resources Model: State of The ArtHarpreet AjimalNo ratings yet

- Psihologia PozitivaDocument10 pagesPsihologia PozitivaClaudiaClotanNo ratings yet

- Thinking Creatively at WorkDocument4 pagesThinking Creatively at WorkCharis ClarindaNo ratings yet

- A Study of Marital Conflict On Measures of Social Support and Mental HealthDocument14 pagesA Study of Marital Conflict On Measures of Social Support and Mental HealthSunway UniversityNo ratings yet

- Dispositional Resistance To ChangeDocument1 pageDispositional Resistance To ChangesoregsoregNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Among Achievement Motivation, Psychological Contract and Work AttitudesDocument9 pagesThe Relationship Among Achievement Motivation, Psychological Contract and Work AttitudesFakhrul IslamNo ratings yet

- Teacher Beliefs and Stress JRECBTDocument17 pagesTeacher Beliefs and Stress JRECBTandreea_zgrNo ratings yet

- Lecture 12 Conflict and StressDocument39 pagesLecture 12 Conflict and StressAnannya100% (1)

- Baron Model of Emotional Social IntelligenceDocument28 pagesBaron Model of Emotional Social IntelligenceglaenriqNo ratings yet

- Chinese Teique SFDocument8 pagesChinese Teique SFSarmad Hussain ChNo ratings yet

- Lewin (1939) Field Theory and Experiment in Social PsychologyDocument30 pagesLewin (1939) Field Theory and Experiment in Social PsychologyVicky MontánNo ratings yet

- OB DaftDocument11 pagesOB DaftDjy DuhamyNo ratings yet

- Psychological Capital (Psycap) in Nigeria Adaptation of Luthan's Postive Psychological Capital Questionnaire (Pcq-24) For Nigerian SamplesDocument10 pagesPsychological Capital (Psycap) in Nigeria Adaptation of Luthan's Postive Psychological Capital Questionnaire (Pcq-24) For Nigerian SamplesInternational Journal of Advance Study and Research WorkNo ratings yet

- CIPD Organisation Development FactsheetDocument6 pagesCIPD Organisation Development FactsheetayeshajamilafridiNo ratings yet

- Marital Satisfaction in Dual Earner FamilyDocument4 pagesMarital Satisfaction in Dual Earner FamilyInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Measures of Fatigue: Geri B. NeubergerDocument9 pagesMeasures of Fatigue: Geri B. NeubergerSanda GainaNo ratings yet

- Organizational Police Stress Questionnaire PSQ OrgDocument2 pagesOrganizational Police Stress Questionnaire PSQ OrgcarmiaNo ratings yet

- Leanne E. Atwater, David A. Waldman - Leadership, Feedback and The Open Communication Gap (2007) PDFDocument178 pagesLeanne E. Atwater, David A. Waldman - Leadership, Feedback and The Open Communication Gap (2007) PDFjanti100% (1)

- Exploring Organizational Virtuousness & PerformanceDocument24 pagesExploring Organizational Virtuousness & PerformanceLyndee GohNo ratings yet

- Two-Factor TheoryDocument4 pagesTwo-Factor TheoryAnonymous NKeNrsNo ratings yet

- Jurnal BipolarDocument11 pagesJurnal BipolarRihan Hanri100% (1)

- George Elton MayoDocument6 pagesGeorge Elton Mayoapi-3831590100% (1)

- Stress and Well BeingDocument91 pagesStress and Well BeingJoseph Fkk100% (1)

- Markides 2012 Business Strategy ReviewDocument5 pagesMarkides 2012 Business Strategy ReviewvalentinaNo ratings yet

- Big FiveDocument14 pagesBig FiveMihaela Andreea PsepolschiNo ratings yet

- Boredom StudyDocument56 pagesBoredom StudyTeoNo ratings yet

- Chapiter 1 Understanding StressDocument19 pagesChapiter 1 Understanding StressMateta ElieNo ratings yet

- Organizational Justice-Ceylan SuluDocument14 pagesOrganizational Justice-Ceylan SuluproffsyedNo ratings yet

- Power Distance IndexDocument5 pagesPower Distance IndexproffsyedNo ratings yet

- Economic and Industrial Democracy 2007 Rigotti 212 38Document28 pagesEconomic and Industrial Democracy 2007 Rigotti 212 38proffsyedNo ratings yet

- Power Distance IndexDocument5 pagesPower Distance IndexproffsyedNo ratings yet

- Law of Diminishing RetDocument2 pagesLaw of Diminishing RetproffsyedNo ratings yet

- Windows TermDocument15 pagesWindows TermproffsyedNo ratings yet

- What Do You Mean by Producer EquilibriumDocument10 pagesWhat Do You Mean by Producer EquilibriumproffsyedNo ratings yet

- The Hysteresis Loop and Magnetic PropertiesDocument2 pagesThe Hysteresis Loop and Magnetic PropertiesproffsyedNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan PhilosoDocument2 pagesLesson Plan PhilosoproffsyedNo ratings yet

- 10-Feature of A Decisive SituationDocument15 pages10-Feature of A Decisive SituationproffsyedNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument3 pagesUntitledproffsyedNo ratings yet

- Perfrmance Apraisal-Wworking PaperDocument7 pagesPerfrmance Apraisal-Wworking PaperproffsyedNo ratings yet

- The Hysteresis Loop and Magnetic PropertiesDocument2 pagesThe Hysteresis Loop and Magnetic PropertiesproffsyedNo ratings yet

- 8 - Steps To Lesson PlanDocument1 page8 - Steps To Lesson PlanproffsyedNo ratings yet

- HCR V3 Rating Sheet 2 Page CC License 16 October 2013Document2 pagesHCR V3 Rating Sheet 2 Page CC License 16 October 2013minodora100% (2)

- WHLP in Oral Comm - Week # 3Document2 pagesWHLP in Oral Comm - Week # 3Lhen Unico Tercero - BorjaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Foundations of PlanningDocument20 pagesChapter 8 - Foundations of Planningish ishokNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document4 pagesModule 2Frances Marella CristobalNo ratings yet

- Ippd 2015-2016Document3 pagesIppd 2015-2016Arman Villagracia94% (34)

- Learning Styles BibliographyDocument3 pagesLearning Styles BibliographyJason NeifferNo ratings yet

- Reflection (Intuitive Ability Survey)Document3 pagesReflection (Intuitive Ability Survey)Abren DaysoNo ratings yet

- Hauptman Reading Disclosure StatementDocument3 pagesHauptman Reading Disclosure Statementapi-240196080No ratings yet

- Week 8 Assignment (Perception)Document2 pagesWeek 8 Assignment (Perception)JASFEEQREE BIN JASMIH -No ratings yet

- Tesol Video QuestionsDocument3 pagesTesol Video QuestionsŁéī ŸáhNo ratings yet

- Peer To Peer Classroom Observation FormDocument2 pagesPeer To Peer Classroom Observation FormlatifaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Primary 3 VIDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Primary 3 VINELAIDA CASTILLONo ratings yet

- CH 6Document16 pagesCH 6Yaregal YeshiwasNo ratings yet

- Augustinian LeadershipDocument33 pagesAugustinian LeadershipEnrico HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Joshua Lagonoy - Activity 1Document2 pagesJoshua Lagonoy - Activity 1Joshua LagonoyNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan DLP F1 3 - 2 Writing - 2Document1 pageDaily Lesson Plan DLP F1 3 - 2 Writing - 2chezdinNo ratings yet

- NFDN 2006Document2 pagesNFDN 2006api-321581670100% (2)

- New Psycho ReportDocument18 pagesNew Psycho ReportnavquaNo ratings yet

- Reenforcement TheoryDocument3 pagesReenforcement TheoryRAHUL GUPTANo ratings yet

- Childhood Depression Brochure PortfolioDocument2 pagesChildhood Depression Brochure Portfolioapi-357520640No ratings yet

- IIIDocument7 pagesIIIAirish DaysonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8: Appraising and Managing Performance: Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument13 pagesChapter 8: Appraising and Managing Performance: Multiple Choice QuestionsankitNo ratings yet

- PTLLS - Micro Teach - Scheme of WorkDocument12 pagesPTLLS - Micro Teach - Scheme of WorkAminderKNijjar100% (1)

- TRF - Objective 9 - Prompt 2Document3 pagesTRF - Objective 9 - Prompt 2Iza Mari Victoria LechidoNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Good Study Habits: Foreign LiteratureDocument7 pagesThe Effects of Good Study Habits: Foreign LiteratureEterna LokiNo ratings yet

- Greene Dessie - Vocabulary Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesGreene Dessie - Vocabulary Lesson Planapi-282800155No ratings yet

- The Science of Personal Achievement by Napoleon HillDocument1 pageThe Science of Personal Achievement by Napoleon Hillskim0000No ratings yet

- TP Leadership QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesTP Leadership Questionnairemanik_elaNo ratings yet

- Reflection For Occupation-BasedDocument2 pagesReflection For Occupation-Basedapi-291545292No ratings yet

- Employee FirstDocument4 pagesEmployee Firstanon_806011137No ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionFrom EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2475)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (560)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (233)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)No ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Summary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeFrom EverandSummary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelFrom EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeFrom EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3226)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverFrom EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (186)

- The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessFrom EverandThe Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (456)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeFrom EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)

- Codependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for YourselfFrom EverandCodependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for YourselfRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (88)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageFrom EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (10)

- The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeFrom EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsFrom EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (709)