Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(Paper) Fernandez Costales

Uploaded by

fanzefirlOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(Paper) Fernandez Costales

Uploaded by

fanzefirlCopyright:

Available Formats

Translation 2.0.

The localization of institutional websites

under the scope of functionalist approaches

Alberto FERNNDEZ COSTALES

University of Oviedo

Abstract

The current paper addresses the importance of localization and its role within

Translation Studies. Besides explaining the concept of localization, we will focus on the

benefits of localizing for both companies and users. The possible advantages for

institutions will also be suggested in a different level.

Since localization is a purpose-driven process, we propose applying the Skopostheorie

in order to provide a theoretical ground to the particular case of website localization. In

addition we will briefly comment on the eternal question of whether localization and

translation are the same discipline or not, focusing on the concept of traditional

translation used in the localization industry.

As it is exposed in this article, there are a number of paradoxes that need to be solved in

the case of localization of institutional web pages. The impact of adapting websites for

higher education institutions and its possible influence on students mobility constitute

the foothold for the authors PhD, centred in the internationalization of websites in the

case of European Union universities.

1. Introduction

In the last decades the concepts of localization and internationalization have broken into

the international panorama involving quite an important number of areas and

disciplines, including Translation Studies. The ongoing effects of globalization have

reached areas far-distant from economy and have affected practically all spheres in our

society (Schffner 2000: 1). In addition to the new global configuration, we have

witnessed the explosion of the Internet and its development as an informative source

and a communication device used by millions of people every day. In this scenario,

translation is not only the basic tool for intercultural communication and a vehicle for

understanding among nations (Wiersema 2004), but it has turned into an essential

element for the economy of every company seeking an international presence beyond

the borders of its home country (Thibodeau 2000: 127, Corte 2002).

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

2. Localization

In order to promote localization, and to foster its industry and best practices the

Localization Industry Standards Association (also known as LISA) was created in 1990.

This institution offers an official definition of the concept in its Localization Primer:

Localization is the process of modifying products or services to account for

differences in distinct markets. While this definition sounds simple, it actually

impacts many business and technical issues and requires a good deal of expertise

to implement successfully. Localization involves the adaptation of any aspect of

a product or service that is needed for a product to be sold or used in another

market. This process significantly impacts both technical and business functions

within organizations. This includes how sales are made; how products and

services are designed, built and supported; how financial reporting systems are

implemented; and so on. (LISA 2007: 11)

Localization has been widely discussed by multiple scholars and researches (Corte

2000; Esselink 2000; Austermhl 2001; OHagan & Ashworth 2002; Yunker 2002;

Pym 2005) and it is commonly accepted that this process aims to adapt a product into a

particular locale1 so that the final user does not perceive that it has been created in

another language under the umbrella of a different culture (Corte 2002). In order to

achieve this objective, localization involves not only translating the text into the target

language but also dealing with all semiotic and non-textual elements that the product

may convey: colours, images and icons, currencies, date formats, and so on (Esselink

2000: 33; Yunker 2002: 477).

One of the main premises of localization is to meet the requirements or standards

established in the target locale, thus the necessary modifications have to be done in

order to satisfy the final user of the product. Sprung illustrated all this with a very

didactic example of how localization works:

Localization is commonly defined as the process of taking a product hopefully

one that has been well internationalized- and adapting it to a specific locale or

target market or language group (translation is thus a subset of localization). An

example may help illustrate the point: designing an automobile chassis so that

the steering wheel could be installed on either the right or left would be a case of

The term locale is understood here in the sense defined by Anthony Pym: Those features of the

customers environment that are dependent upon language, country/region and cultural conventions

(Pym 1999).

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

2

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

internationalization. The decision to actually make a given bath of cars leftsteering would be a case of localization. (Sprung 2000: xvii)

2.1. Why localizing? Benefits for companies & users

The world has shrunk due to the effects of globalization (Wiersema 2004), and in this

new situation localization is intended to cover the increasing demand for the adaptation

of contents. But why do companies really want to localize their products? Is it a must

to release a videogame or a software application in several languages at the same time?

Localization offers a wide range of benefits for companies that can be easily

understood by having a look at some figures. According to LISA, the global investment

in localization accounts for $ 5 billion per year, although if all the vertical markets were

included this amount could be as high as $15 billion (LISA 2007: 8). Similarly,

Thibodeau states that American software companies obtain 50% of their incomes from

international sales, and the translation of the products from English into other languages

increments the total sales of a vendor about 25%

(Thibodeau 2000: 127). It is

expectable that any company that localises its products will gain market share by

breaking into new markets and having more comparative advantages over its

competitors.

Moreover, legal restrictions and barriers can also be lifted if localization is

carried out in an appropriate way. To illustrate this with an example, we can take the

sector of transport and logistics, where time actually is money: the more time a ship is

in a dock, the more taxes and duties will have to be paid by the carrier (and by the final

consignee). In this case, the correct localization of products, software applications or

manuals to the destination locale will have a crucial importance in the performance of

workers and employees. Wagner Covos underlines the importance of localization for

economical and legal purposes in this descriptive example:

When a nylon shoulder for v-shear ram block screw is imported by a

company located in Brazil, the item is generally described on the invoice as a

simple screw. In order for the part to comply with the strict criteria of the

customs examination, the invoice translation must specify that it is part of a

blowout preventer (BOP), a piece of oilfield exploration equipment. Therefore,

if the term is translated into Portuguese and classified as parafuso de nylon de

ressalto para bloco de gaveta de corte, the customer will be able to benefit from

the associated tax exemption. On the other hand, if the word is not localized

and translated simply as parafuso, the inspectors will not be able to determine

whether the item is intended for the target activity or if they are dealing with a

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

3

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

screw for a washing machine. Hence, the inspectors will not be able to apply the

usual tax exemption rules, which would otherwise benefit the importer of the

item. (Covos 2005)

Regarding the final users of the product, if this has been localized, they will have

immediate access to the information in their own native language, what makes them

more efficient and competent (Wallis 2006: 3). In the case of websites, localization

helps to implement factors such as usability and accessibility that will allow millions of

people to exchange information in the web in an efficient manner. This statement is

supported by research in the context of web pages, where users perceive a company

more favourably when they see a version of its website in their mother tongue,

regardless of their English proficiency (Tong and Hayward 2001: 4).

3. Translation vs. localization

Whether translation and localization are the same concept or not is a rather complex and

controversial issue that has been discussed in several research articles and debates.

From the point of view of the localization industry, one of the most accepted ideas is

that localization is a wider process than translation and that it involves a number of

additional tasks. This has been summarized by Bert Esselink, who provides a quite clear

definition of the position of the sector on this matter: Translation is only one of the

activities in localization; in addition to translation, a localization project includes many

other tasks such as project management, software engineering, and desktop publishing

(Esselink 2000: 4). This is an official view supported by many professionals (Dohler

1997; Donoso 2002; Scholand 2002; Arevalillo 2004).

Localization can provide new insights into translation practice, but there are

certain weaknesses to be spotted. Even though there is a whole industry supported by

institutions like LISA or GALA, there is a certain lack of theoretical framework

underpinning localization that can be effectively supplied by Translation Studies. As

Anthony Pym suggests in one of his articles addressing this topic:

Translation theory has a lot to learn from localization. Efficiency, teamwork,

client-liaison and technology-know-how are just a few examples. So why would

localization have nothing to learn from translation theory? (Pym 2006)

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

4

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

In fact, Translation Studies can offer a whole background to explain some of the most

common problems and hurdles localizers have to tackle every day. In this article we

support the hypothesis that functionalist approaches can be used to analyse and explain

the basics of localization, as several researchers have already pointed (Maroto 2005;

Sandrini 2005; Nauert 2007). To the previous question what has localization to learn

from translation theory? we propose a very concise answer here, viz. Skopostheorie.

The Skopostheorie was enunciated by Hans Vermeer in 1978 and later

developed into a more general theory together with Katherina Reiss in the classical

Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie (1984). In the 90s, this translation

theory was enriched by the contributions made by Christiane Nord (1991; 1997). Since

this is a functionalist theory, the communicative and socio-cultural aspects of translation

will be highlighted as a point of differentiation from other, more linguistically driven

approaches to translation (Schffner 2001: 235).

The main ideas to be drawn from the Skopostheorie establish that translation is a

human action determined by the purpose (the skopos in Greek) it has to fulfil. Hence,

the function to be accomplished by the target text and the effect it aims to produce in the

final receivers are the elements that will determine the translation strategies to be

followed by the translator. This conclusion is expressed by the formula IA (Trl) = f(Sk)

(Vermeer 1978: 100) that states that translation is a human action determined by its

purpose. In other words, translation is a function of its skopos.

This theory places an enormous emphasis on the importance of the target text

(with the source text loosing some of its traditional importance) and also awards the

translator a relevant role in the process of transferring the message between cultures. In

this regard, the translator becomes an expert and the cultural mediator (or cultural

worker, quoting Gentzler 2001: 71) that has to overcome all the difficulties and

challenges of conveying the message to the final receiver. In this context, the

instructions provided by the commissioner or initiator of the process the translation

brief according to Christiane Nord (1997: 30) do have something to say, as we will

state later on in this paper.

A key element to bear in mind when talking about the Skopostheorie (and for the

purpose of this paper) is the concept of loyalty coined by Christiane Nord in 1991.

The translator is committed bilaterally to the source and the target situations

and is responsible to both the ST sender (or the initiator, if he is the one who

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

5

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

takes the senders part) and the TT recipient. This responsibility is what I

call loyalty. Loyalty is a moral principle indispensable in the relationships

between human beings who are partners in a communication process. (Nord

1991: 94)

Since translation is a human action according to Vermeer (1978), loyalty is a necessary

and indispensable element for this process to be considered truly functional. In addition,

this particular notion stands for a valuable tool in the case of website localization, as we

will try to explain in the following paragraphs.

The aim of this paper is not to give a comprehensive description of the

functionalist approaches in translation but to outline how Skopostheorie can be applied

to website localization, as well as how it can give a theoretical answer to certain

questions. In fact, a functionalist approach has already been used in the analysis of

promotional texts (Valds 2004; Maroto 2005), and even web localization (Sandrini

2005). Some of the main criticisms on this theory like the difficulty of applying the

scopos to literary texts (Snell-Hornby 1990: 84) are not commented on this article

since we are dealing with more technical texts.

So, what exactly can Skopostheorie contribute to the study of localization? As

we have already mentioned, localization is a target-oriented process in which the final

product has to fulfil a precise function. This is in accordance with the functional

approach of Vermeer: localization is determined by the particular skopos of every

singular project. In addition, the role of the commissioner and the translation brief are

major concerns in the case of localization since it is a market-driven process that

follows the constraints of practices such as simultaneous shipment or simship, where

several versions of the same product are released in different markets at the same time

(Esselink 2000: 111).

Arguably, the single most interesting point for research is the role of the

translator or localizer within the process. Localization industry professionals and even

some translation scholars claim localizers have a tremendous freedom when modifying

and adapting the products to suit the final audience expectations, with the coinage of

transcreation (Mangiron & OHagan 2006) to refer to this kind of liberty. However,

some voices have already contradicted the creation of a neologism that has nothing new

to offer to the concept of translation, where creativity and translators freedom are

already included (Bernal 2006). In this context, we suggest Christiane Nords notion of

loyalty to be explored and applied to the particular case of localization. As a moral

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

6

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

principle, loyalty should be used in order to guarantee translators responsibility and to

settle a kind of firewall towards an excessive freedom of choice. This is the case

particularly with website localization, where the translator should keep in mind his/her

role as cultural expert in a communicative action.

So far we have exposed how functionalist approaches can be applied to

localization in order to explain some of the features of this process. However, we should

address the wider issue of the status of localization regarding Translation Studies. One

of the problems we are facing when dealing with this question is the concept of

translation that is commonly used in the localization industry:

Software localisation is different from the traditional concept of translation in

the sense that the former calls for the linguistic transfer to be combined with

software engineering, as the translated strings (lines of text) need to be compiled

back into the given software environment. (Mangiron & OHagan 2006)

The concept of traditional translation is frequently used in localization handbooks and

articles (Esselink 2000: 2; Arevalillo 2004). However, from a critical point of view it is

not clear or specified what is understood as traditional translation (maybe word-forword transfer?) but it seems the progress achieved the last 20 years in the field of

Translation Studies is being ignored (Pym 2006). In this sense, localization could be

compared to more recent trends in translation like Audiovisual Translation where

more technical processes are also required (dubbing, subtitling) and several tasks are

performed simultaneously, as in the case of the film industry. The comparison with

Audiovisual Translation is also useful since this field or specialization has of late been

included in research topics and academic life.

In this paper we defend the hypothesis that translation and localization share the

common objective of transferring a text to a specific culture. If we assume a

multidimensional vision of translation as suggested by Nauert (2007) or just reject the

use of the concept traditional translation we can reach a meeting point where

adaptation is a broader term covering both items. It does not mean that we are ignoring

the claims that localization goes beyond translation (since the former incorporates more

tasks), but such differences do not make translation and localization mutually exclusive.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

7

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

4. The basics of localization

Many of the core features of localization have already been suggested in this paper (e.g.

adaptation of images, number formats and cultural elements, in addition to the

translation of text strings), but some of these factors need to be reviewed in order to

understand how this process works. Due to market constraints, localization is a

simultaneous process that goes along with the development of the product (Arevalillo

2004). In addition, localization involves a series of tasks and activities that have to be

tackled in order to consider a product to be successfully adapted. The following is a

checklist with some of the most common points to bear in mind:

Text: Although localization is primarily carried out in the so-called FIGS

languages French, Italian, German and Spanish plus Japanese (Esselink 2000: 8),

Chinese and other languages have gained a notorious importance in the last decades,

especially on the Web (as explained in section 5). Directionality of the text is an issue to

be addressed since some languages like Arabic are written from right to left (Yunker

2002: 395). Also, encoding and language character sets need to be reviewed in order to

make sure the application or website will display certain characters (e.g. ideographs) in

the right way.

Colours: They need to be adapted since some tonalities could constitute a

cultural pitfall when shown in some countries. White is used in funeral pyres in China

and green is a sacred colour in many Arabian countries (Yunker 2002: 485). These are

just some samples of the subtle complexities that colours can provoke when dealing

with different cultures.

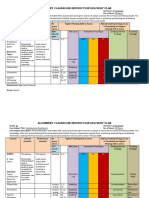

Images: The use of images constitutes a potential danger when adapting the text

to a different locale. Special attention should be paid to the use of animals (e.g. cows are

sacred in India) or any religious symbol (e.g. crucifixes) that could constitute a problem

in the destination country (Corte 2002). Also, the typical bitmaps used in computer

programs (e.g. the mailbox to indicate you have an e-mail) have to be studied and

analyzed since not all the countries and cultures are familiarized with certain Western

conventions (Esselink 2000: 112; Yunker 2002: 307). Illustration 1 shows a very simple

example of the problems that the use of images can generate in a software application2.

The term run is used in English when we want to execute an application or perform an

2

The example is taken from the authors dissertation on software localization. The icons have been

modified with the permission of the developers of the application HOM 3.0.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

8

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

action in a specific programme. Then, the association of the concept with the icon of a

runner would be understandable in any English-speaking context. However, if the

application is to be localized into Spanish, this bitmap has to be modified since the term

correr (Spanish translation for run) is not valid for this context and the button would

be absolutely meaningless.

Illustration 1. Bitmaps adapted from English into Spanish in the localization of the

application HOM 3.0.

Date formats and calendar: The Gregorian calendar has to be switched to any

different format used in other cultures (e.g. Chinese calendar, Muslim calendar).

Besides, dates are expressed differently according to diverse countries and regions. For

instance, the date is expressed using the format mm-dd-yyyy in the United States and

with the format dd-mm-yyyy in Spain (12-25-2008 vs. 25-12-2008).

Currency and numeric formats: Besides the appropriate currency used in each

country, the way it is expressed in the target locale should be altered: In some languages

like English, the currency symbol precedes the number, while in others like Spanish the

symbol goes after it (Donoso 2002). Also, the way in which numbers are written

changes depending of the locale: the number 1,650 in the UK would turn into 1.650 in

Spain.

Legal issues: When localizing a software application, a videogame or a web

page, a thorough knowledge of any possible legal restrictions in the target locale is

required. For instance, blood must be removed (or given a green colour) in Germany in

order to meet legal regulations (Chandler 2005: 10). Another example can be found in

France, where due to the Toubon Law3, commercial contracts or advertisements have to

be translated into French with no exception.

Size of menus, dialogues and boxes: Space restrictions constitute one of the

most important hurdles that localizers have to solve in order to have a neat final product.

When we are translating from English into other languages, the resulting text usually

expands. For instance, if we are working with English as the source text, we have to

realise that the final version when translating to other languages will be about 20% to

3

The text of the Toubon Law is accessible at http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

9

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

10

30% longer than the original (Esselink 2000: 33; Chandler 2005: 5). It means that we

will have to resize the GUI (Graphic User Interface) in the case of software

applications, or the structure of the web page we are localizing.

Illustration 2. Example of space restrictions in the localization of a toolbar from

English into Spanish using Passolo 6.0.

These are some of the most common points to bear in mind in any localization project.

If we use a global perspective it seems quite clear that all the efforts of localization are

put into achieving a certain goal in the final destination or locale (i.e. preserve the user

experience). This is akin to what functionalist scholars defend in their theories, as we

have previously outlined in this paper. In fact, not only Skopostheorie can be useful to

explain how localization woks. In a quite interesting paradox, Anthony Pym (2006) uses

a more traditional translation source to explain some of the features here mentioned:

Nidas concept of dynamic equivalence covers different aspects of cultural adaptation.

This could also be used in order to explain and support the previous checklist from a

theoretical point of view.

5. The World Wide Web

In the last decades Internet has become the real information highway of our lives. We

are able to obtain precise data in real-time from any part of the world. With the growing

importance of the Web and the improvement in infrastructures, more and more people

have gained access to the Internet, and subsequently more and more users are looking

for information in their own language (see illustration 3). As it has been expounded in

this paper, localizing contents is an important tool in order to adapt any text to a specific

locale. Moreover, English has been losing power on the Web with the emergence of

other languages that are growing at a faster pace in the case of information technologies

(Corte 2000: 9; Corte 2002; Yunker 2002: 23-24). According to Internet World Stats,

29.4% of web users are native speakers of English (430 million users); that means that

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

10

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

11

70.6% of the total users do not have English as their mother tongue4. This is a thoughtprovoking figure that comes to underline the importance translation can have on the

World Wide Web. In fact, the analysis of web localization and translation has turned

into a fertile field for the study of promotional discourse (Pierini 2007; Valds 2008).

Illustration 3. Top ten languages used in the web according to the number of

native speakers. Source: Internet World Stats.

As shown in the table, English has a lower growth rate than many other languages in the

Internet top ten (Arabic, Chinese or Spanish are growing much faster). Considering this

information and thinking about the increasing number of users accessing the web from

non-English speaking countries, we could expect that there is an established golden rule

for websites by which all the pages are translated into several different languages.

Even though companies have understood the profits that can be obtained from

the localization of their websites, it looks as if in the case of institutions the situation is

not so clear. If we compare the website of a well-known company like IKEA

(www.ikea.com/) with another world-famous institution as the White House

(www.whitehouse.gov) we will be shocked by the fact that in the case of the Swedish

furniture retailer the web has been adapted to 37 locales (see illustration 4), while in the

case of the American political symbol, we can only find a (partial) translation into

Spanish. Obviously, this is just a random sample and it cannot be used as a general rule.

However, it looks quite clear that the company is motivated by the important revenues it

is going to get in those 37 different locations (that will pay off any investment in

4

Source: Internet World Stats (http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm accessed: June 2009)

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

11

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

12

translating the site), and the White House is addressing the 45 million Spanish speakers

(more than the total population in Spain) currently living and many of them voting

in the USA5.

The idea of this paper is that in the case of institutions, English is still the lingua

franca used in order to become global.

Illustration 4: Splash page of IKEA with the locale selector (accessed: June 2009).

6. Institutions go global: The case of university web pages

Localization has been studied in the case of videogames (Chandler 2005; Bernal 2006),

software (Dohler 1997; Esselink 2000) and also websites (Yunker 2002; Nauert 2007),

although attention has been drawn primarily towards private companies. That is why

there is a necessity to verify which is the situation with institutional websites.

In the case of universities, having an international site is not only important with

regard to quality standards and other factors like usability and accessibility of the

contents. The hypothesis of the research being carried out is that website

internationalization could also have some influence on the number of foreign students

that institutions receive every year. The figures related to the amount of research

Source: El Pas 23 June 2009. On line at:

http://www.elpais.com/articulo/cultura/speak/spanish/Espana/elpepucul/20081006elpepicul_1/Tes

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

12

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

13

activities and scholar exchange among institutions could also be affected by the

adaptation of university websites.

There are several questions to be formulated here. The first one would be to

determine if it is strictly necessary that all university websites should be translated into

English. In addition, what kind of English is being used in the websites? Are we

confronting International English or McLanguage as a standard in the Internet due

to the effects of globalization (Snell-Hornby 2000: 12)?

The other big issue to be addressed here would be the question of language

policy and multilingualism in higher education institutions. For this matter it could be

interesting to find out about the decision makers in the case of website translations:

Who does what? Are translations being made by professional translators? Who decides

which languages a certain website should contain?

As regards student mobility, research is needed to assess the impact of

translating websites into more than one language. Do websites in English attract more

international students? This point is closely linked to other elements such as usability

and accessibility. An Erasmus student looking for study plans in any Business School in

Spain would prefer attending a university which provides translated contents in its

website (subjects, language courses, information for international students, etc). This

could contribute to the analysis of discursive aspects in university websites, taking into

account all the textual, intertextual and semiotic components.

All these questions are being tackled in an on-going research project in which

the authors PhD is based. Having gathered an extensive corpus of university websites,

a thorough analysis is being performed in order to obtain some answers to the problems

presented in this article. The role of the translator in the adaptation of university web

sites is being studied, trying to apply the postulates of the Skopostheory and analyzing

how the concept of loyalty is respected (or not). Besides, the question of

multilingualism in higher education is to be addressed with a special focus on the kind

of language used in university websites (International English) as a consequence of

globalization effects in institutions.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

13

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

14

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

7. Conclusions

This paper aims to shed some light to the basics of localization from the point of view

of Translation Studies. Some of the main features of this process have been expounded,

as well as a brief explanation of the importance of adapting contents to the different

locales or target markets where the products are going to be published.

One of the fields in which research into localization can be more productive in

the short term is related to institutional websites. If we assume multilingualism is a

major concern for European institutions, it is a must to improve the way these

institutions are present on the World Wide Web and to ensure the quality of web content

adaptation into different cultures.

As has been stated, Translation Studies has many things to offer to localization.

The insights and perspectives of translation theories such as the Skopostheorie can offer

valuable foundations for a process that is also constrained by the speed of the markets.

On the other hand, Translation Studies can benefit from research into localization, and

collaboration with the industry would be mutually profitable.

As a concluding remark, it is important to repeat that translation is far away from

the traditional concept handled in some debates. As the concept evolves and more

scholars are working in new research lines, the horizons have been enlarged. Hence, a

label such as Translation 2.0 could be meaningful in order to express the interaction of

translation and its professionals with other areas and fields of knowledge.

Interdisciplinarity is a key element that will bring important benefits for both scholars

and professionals, and it has to be supported by the scientific community.

References

Arevalillo Doval, Juan Jos. 2004. Introduccin a la localizacin, su presencia en el

mercado y su formacin especfica. La Linterna del Traductor 8: 28-48.

Retrieved 23 June 2009 from: http://traduccion.rediris.es/8/loca0.htm.

Austermhl, Frank. 2001. Electronic Tools for Translators. Manchester: St. Jerome.

Bernal, Miguel. 2006. On the Translation of Video Games. The Journal of Specialised

Translation

6:

22-36.

Retrieved

22

June

2009

from:

http://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_bernal.php.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

14

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

15

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

Chandler, Heather M. 2005. The Game Localization Handbook. Massachusetts: Charles

River Media INC.

Corte, Noelia. 2000. Web Site Localization and Internationalisation: a Case Study. PhD

dissertation.

Retrieved

22

June

2009

from:

http://www.localization.ie/resources/Awards/Theses/Theses.htm.

Corte, Noelia. 2002. Localizacin e internacionalizacin de sitios web. Tradumtica

1.

Retrieved

22

June

2009

from:

http://www.fti.uab.es/tradumatica/revista/articles/ncorte/art.htm.

Covos, Wagner. 2005. Using Translation to Cut Costs in the Energy Sector. Ccaps

Newsletter 15. 22 June 2009 from: http://www.ccaps.net/newsletter/0405/newsletteren.htm.

Dohler, Per N. 1997. Facets of Software Localization. Translation Journal 1 (1).

Retrieved 19 June 2009 from: http://accurapid.com/journal/softloc.htm.

Donoso, Feliciano. 2002. Internationalisation. Tradumtica 1. Retrieved 19 June 2009

from: http://www.fti.uab.es/tradumatica/revista/articles/fdonoso/art.htm.

Esselink, Bert. 2000. A Practical Guide to Localization. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gentzler, Edwin. 2001. Contemporary Translation Theories. London and New York:

Routledge.

LISA. 2007. The Globalization Industry Primer: An Introduction to preparing your

business and products for success in international markets. 24 Retrieved June

2009 from: http://www.lisa.org.

Mangiron, Carmen & OHagan Minako. 2006. Game Localization: Unleashing

imagination with Restricted Translation. The Journal of Specialised

Translation

6.

Retrieved

19

June

2009

from:

http://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_ohagan.php.

Maroto, Jess. 2005. Cross-cultural Digital Marketing in the Age of Globalization: An

analysis of the current environment, theory & practice of global advertising

strategies and a proposal for a new framework for the development of

international

campaigns.

Retrieved

19

June

2009

from:

http://www.jesusmaroto.com.

Nauert, Sandra. 2007. Translating Websites. Acts of the LSP Translation Scenarios

(MuTra).

Conference

proceedings.

Vienna.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

15

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

16

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2007_Proceedings/2007_Nauert_Sandra

.pdf.

Nord, Christiane. 1991. "Scopos, loyalty and translational conventions." Target 3 (1):

91-109.

Nord, Christiane. 1997. Translating as a Purposeful Activity. Functionalist Approaches

Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome.

OHagan, Minako & Ashworth, David. 2002. Translation-Mediated Communication in

a Digital World: Facing the Challenges of Globalization and Localization.

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Pierini, Patrizia. 2007. Quality in Web Translation: An Investigation into UK and

Italian Tourism Web Sites. The Journal of Specialised Translation 8: 85-103.

Retrieved 20 June 2009 from: http://www.jostrans.org/issue08/art_pierini.php.

Pym, Anthony. 1999. Localizing localization in translator-training curricula.

Linguistica Antverpiensia 33: 127-137.

Pym, Anthony. 2003. What Localization Models can Learn from Translation theory?.

The LISA Newsletter. Globalization Insider 12. Retrieved 24 June 2009 from:

http://www.tinet.org/~apym/on-line/translation/translation.html.

Pym, Anthony. 2005. Localization: On its nature, virtues and dangers. Retrieved 24

June 2009 from: http://www.tinet.org/~apym/on-line/translation/translation.html.

Pym, Anthony. 2006. Localization, training & the threat of fragmentation. Retrieved

24

June

2009

from:

http://www.tinet.org/~apym/on-

line/translation/translation.html.

Reiss, Katharina and Vermeer, Hans. J. 1984. Grundlegung einer allgemeinen

Translationstheorie. Tbingen: Niemeyer.

Sandrini, Peter. 2005. Website Localization and Translation. Acts of the Challenges

of

Multidimensional

Saarbrcken.

Translation

Retrieved

(MuTra).

24

Conference

June

proceedings.

2009

from:

www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2005_Proceedings/2005_Sandrini_Peter

.pdf.

Schffner, Christina. 1998. Skopos theory. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation

Studies, Mona Baker (ed.). London and New York: Routledge. 235-238.

Schffner, Christina (ed.). 2000. Translation in the Global Village. Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

16

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

17

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

Scholand, Michael. 2002. Localizacin de videojuegos. Tradumtica 1. Retrieved 24

June

2009

from:

http://www.fti.uab.es/tradumatica/revista/articles/mscholand/art.htm.

Snell-Hornby, Mary. 1990. Linguistic transcoding or cultural transfer? A critique of

translation theory in Germany. In Translation, History, and Culture, Susan

Bassnett and Andr Lefevere (eds.). London: Pinter. 79-86.

Snell-Hornby, Mary (2000) Communicating in the Global Village: On Language,

Translation and Cultural Identity. In Translation in the Global Village,

Christina Schffner (ed.). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. 11-28.

Sprung, Robert C. (ed.) 2000. Translating Into Success: Cutting-edge strategies for

going multilingual in a global age. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Thibodeau, Ricky P. 2000. Making a Global Product at MapInfo Corporation. In

Translating Into Success: Cutting-edge strategies for going multilingual in a

global age, Robert C. Sprung (ed.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 127-146.

Tong, Kwok-Kit and Hayward, William G. 2001. Speaking the right language in

website design. Conclusions of the study carried out by the department of

psychology and the department of management, Chinese University of Hong

Kong, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong.

United Nations. 1999: Role of the United Nations in promoting development in the

context of globalization and interdependence. Report of the UN Secretary

General at the 54th session of the General Assembly about globalization and

interdependence.

New

York.

Retrieved

12

June

2009

from

http://www.un.org/documents/ga/docs/54/plenary/a54-358.htm.

Valds, Cristina. 2004. La traduccin publicitaria: comunicacin y cultura. Valncia:

Universitat de Valncia. Castell de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat

Jaume I. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Bellaterra: Universitat

Autnoma de Barcelona. Servei de Publicacions, D.L.

Valds, Cristina. 2008. The Localization of Promotional Discourse on the Internet. In

Between Text and Image: Updating research in screen translation, Delia Chiaro,

Christine Heiss and Chiara Bucaria (eds.). Amsterdam and New York: John

Benjamins, 227-240.

Vermeer, Hans J. 1978. Ein Rahmen fr eine allgemeine Translationstheorie. Lebende

Sprachen 23 (1): 99-102.

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

17

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

18

Alberto FERNNDEZ. Translation 2.0

Wallis, Julian. 2006. Interactive Translation vs. Pre-translation in the Context of

Translation Memory Systems: Investigating the effects of translation method on

productivity, quality and translator satisfaction. PhD dissertation. Ottawa.

Retrieved

12

June

2009

from:

http://www.localization.ie/resources/Awards/Theses/Theses.htm.

Wiersema, Nico. 2004. Globalisation and Translation: A discussion of the effect of

globalisation on todays translation. Translation Journal 8 (1). Retrieved 24

June 2009 from: http://accurapid.com/journal/softloc.htm.

Yunker, John. 2002. Beyond Borders: Web Globalization Strategies. Indiana: New

Riders.

About the author

Alberto Fernndez Costales (1978) graduated in English Philology in 2002 at the

University of Oviedo, where he is at present working on a PhD in Translation Studies.

From 2003 to 2008 he coordinated the English training program that the University of

Oviedo developed for the steel company ArcelorMittal in Spain. He continues teaching

technical English courses at the Master of Transport & Logistics Management as well as

other modules regarding international relations in the university. In addition, he works

as a freelance translator and interpreter. Apart from his dissertation topic on

internationalization of websites, his current research interests include audiovisual

translation, translation technology and videogame localization.

Address:

Email:

Jovellanos Business School

University of Oviedo

Laboral Ciudad de la Cultura

Luis Moya 261

33203 Gijn

Asturias, Spain

albertofernandez.fuo@uniovi.es

2009. Dries DE CROM (ed.). Translation and the (Trans)formation of Identities. Selected Papers of the

18

CETRA Research Seminar in Translation Studies 2008. http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html

You might also like

- GILT - Globalization, Internationalization, Localization, TranslationDocument6 pagesGILT - Globalization, Internationalization, Localization, TranslationatbinNo ratings yet

- DT 00001 OhaDocument15 pagesDT 00001 OhaCarolina RamirezNo ratings yet

- Advertising and Localization: January 2012Document20 pagesAdvertising and Localization: January 2012Arianna LainiNo ratings yet

- Localization and TranslationDocument8 pagesLocalization and TranslationPatricia NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Localisation The New Challenge For TransDocument83 pagesLocalisation The New Challenge For TranskoffeyNo ratings yet

- Localization: On Its Nature, Virtues and DangersDocument10 pagesLocalization: On Its Nature, Virtues and DangersTobby47No ratings yet

- Website Localization and Translation - Peter SandriniDocument8 pagesWebsite Localization and Translation - Peter SandriniRuby ChangNo ratings yet

- Print Supp 111Document17 pagesPrint Supp 111Mydays31No ratings yet

- Localization and TranslationDocument14 pagesLocalization and Translationtanya100% (1)

- What Is Internationalization (I18n) - Definition From TechTargetDocument5 pagesWhat Is Internationalization (I18n) - Definition From TechTargetatbinNo ratings yet

- Localization, Globalization, Translation, Etc.: Chapter 1: IntroductionDocument4 pagesLocalization, Globalization, Translation, Etc.: Chapter 1: IntroductionprcarreiraNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Digital Divide, The Future of Localisation: Patrick A.V. HallDocument9 pagesBridging The Digital Divide, The Future of Localisation: Patrick A.V. Hallmarc_ot1No ratings yet

- Localisation Centre For Next Generation LocalisatiDocument11 pagesLocalisation Centre For Next Generation LocalisatiAnna ChyrvaNo ratings yet

- Localization and TranslationDocument6 pagesLocalization and TranslationKaterina PauliucNo ratings yet

- Localization - Lectures 1-3 - StudDocument52 pagesLocalization - Lectures 1-3 - StudSonya MichiNo ratings yet

- Translation and AdvertisingDocument4 pagesTranslation and AdvertisingPetronela NistorNo ratings yet

- Angles 895Document20 pagesAngles 895احمد سلطان حسينNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument8 pagesUntitled DocumentSharan babuNo ratings yet

- Technical TranslationDocument11 pagesTechnical TranslationSharan babuNo ratings yet

- Translation 2.0: Facing The Challenges of The Global Era - Alberto FernándezDocument12 pagesTranslation 2.0: Facing The Challenges of The Global Era - Alberto FernándezEnviando TareasNo ratings yet

- Bianca HAN Translation From Pen and Paper To CAT and MTDocument8 pagesBianca HAN Translation From Pen and Paper To CAT and MTmagur-aNo ratings yet

- Articol 9Document14 pagesArticol 9Ana SpatariNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Translation TechnologiesDocument23 pagesThe Impact of Translation TechnologiesRossana CunhaNo ratings yet

- Quality in Web Translation - PieriniDocument19 pagesQuality in Web Translation - PieriniRita PereiraNo ratings yet

- GILT - Globalization, Internationalization, Localization, Translation - and The Difference Between Them - AD VERBUMDocument12 pagesGILT - Globalization, Internationalization, Localization, Translation - and The Difference Between Them - AD VERBUMatbinNo ratings yet

- Dehydrated Business Plan Audio TranslatorDocument6 pagesDehydrated Business Plan Audio TranslatorAyame DelanoNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Localization (Bert Esselink)Document4 pagesThe Evolution of Localization (Bert Esselink)Juan Yborra Golpe100% (1)

- Electronic Tools For Translators PDFDocument10 pagesElectronic Tools For Translators PDFAntonella MichelliNo ratings yet

- Standards of Translation What Are TheyDocument3 pagesStandards of Translation What Are TheyAliona RussuNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Internationalization ProcessDocument5 pagesThesis On Internationalization Processshaunajoysaltlakecity100% (1)

- I 18 NL 10 N PartnerDocument10 pagesI 18 NL 10 N Partnerapi-3715867No ratings yet

- The Industrialization of Translation. Causes, Consequences and ChallengesDocument26 pagesThe Industrialization of Translation. Causes, Consequences and ChallengesAgnese Morettini100% (1)

- The Multilingual Web: David Filip Dave Lewis Felix SasakiDocument4 pagesThe Multilingual Web: David Filip Dave Lewis Felix SasakiRidho DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Management: An International JournalDocument20 pagesCross Cultural Management: An International JournalBi AdabNo ratings yet

- Vizcaino Et Al 2012Document13 pagesVizcaino Et Al 2012احمد رياض عبداللهNo ratings yet

- Beyond Translation Memory: Computers and The Professional TranslatorDocument16 pagesBeyond Translation Memory: Computers and The Professional TranslatorSantiago BelzaNo ratings yet

- Maria Do Céu Bastos: Orcid: EmailDocument23 pagesMaria Do Céu Bastos: Orcid: EmailMerHamNo ratings yet

- The Proper Place of Professionals (And Non-Professionals and Machines) in Web TranslationDocument8 pagesThe Proper Place of Professionals (And Non-Professionals and Machines) in Web TranslationokkialiNo ratings yet

- Translation TechnologyDocument42 pagesTranslation TechnologyIsra SayedNo ratings yet

- Assignment Cover PageDocument16 pagesAssignment Cover PageAngel KatNo ratings yet

- 209-Book Manuscript-1341-1-10-20181129Document12 pages209-Book Manuscript-1341-1-10-20181129Nguyễn Đan NhiNo ratings yet

- Context Methodology v3Document15 pagesContext Methodology v3Irma YenniNo ratings yet

- Georgakopoulou JoSTrans Issue06 Jul2006Document4 pagesGeorgakopoulou JoSTrans Issue06 Jul2006albertoNo ratings yet

- Screen Supp 57Document25 pagesScreen Supp 57Mydays31No ratings yet

- Flyer What Is TerminologyDocument2 pagesFlyer What Is TerminologyAnonymous 5LNVhpI7VNo ratings yet

- Se Ghiri 2017Document22 pagesSe Ghiri 2017Karol Dayana Castillo HerreraNo ratings yet

- Localization Week 1Document27 pagesLocalization Week 1api-3715867No ratings yet

- Vitikainen Final LockedDocument22 pagesVitikainen Final LockedSasha SchafliNo ratings yet

- Learning Technology Standardization: Making Sense of It All: AbstractDocument11 pagesLearning Technology Standardization: Making Sense of It All: AbstractThiago ReisNo ratings yet

- Terminology For Translators TermbaseDocument330 pagesTerminology For Translators TermbaseKaty DonNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips - Bert Esselink A Practical Guide To Localization Esselink A Practical GuideDocument4 pagesDokumen - Tips - Bert Esselink A Practical Guide To Localization Esselink A Practical Guidepuni13No ratings yet

- International BusinessDocument22 pagesInternational BusinessShrestha Photo studioNo ratings yet

- Thesis Language TranslatorDocument4 pagesThesis Language Translatoraparnaharrisonstamford100% (2)

- Arabize Localization Project ManagementDocument13 pagesArabize Localization Project ManagementLaura Martínez MercaderNo ratings yet

- Multidimensional Quality Metrics: A Flexible System For Assessing Translation QualityDocument7 pagesMultidimensional Quality Metrics: A Flexible System For Assessing Translation QualityRoberta BronzattoNo ratings yet

- TIMReview 2017 Rasmussenand PetersenDocument14 pagesTIMReview 2017 Rasmussenand PetersenMaria Cristina Rodriguez EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Technology Transfer Research PaperDocument4 pagesTechnology Transfer Research Papertehajadof1k3100% (1)

- Iipm Thesis FormatDocument6 pagesIipm Thesis Formatlorribynesbridgeport100% (2)

- B. S Grotesque Sample PDFDocument30 pagesB. S Grotesque Sample PDFCristina MandoiuNo ratings yet

- JamesonDocument9 pagesJamesonfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- 2011-12 Skakov - Ekphrastic Metaphysics of Dzhan - UlbandusDocument17 pages2011-12 Skakov - Ekphrastic Metaphysics of Dzhan - UlbandusfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Kaminskij 231509Document15 pagesKaminskij 231509fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- 0f40ace6c8cc1bf27033e62a0d5a2e27Document231 pages0f40ace6c8cc1bf27033e62a0d5a2e27fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Checkhov PlatonovDocument9 pagesCheckhov PlatonovfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Feminist Research: Debbie Kralik and Antonia M. Van LoonDocument10 pagesFeminist Research: Debbie Kralik and Antonia M. Van LoonfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Roman Ingarden's Theory of Intentional Musical WorkDocument11 pagesRoman Ingarden's Theory of Intentional Musical WorkAnna-Maria ZachNo ratings yet

- Media 192656 enDocument5 pagesMedia 192656 enfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Dolls HouseDocument19 pagesDolls HousefanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Roman IngardenDocument5 pagesRoman IngardenfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Deleuze, Whitehead, and The Truth of Badiou PDFDocument46 pagesDeleuze, Whitehead, and The Truth of Badiou PDFChristos PapasNo ratings yet

- 8673 1 SMDocument32 pages8673 1 SMfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Feminist Performance Criticism1Document25 pagesFeminist Performance Criticism1fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Simpkins - Derrida and SemioticsDocument12 pagesSimpkins - Derrida and SemioticskwsxNo ratings yet

- Resource List of PakistanDocument59 pagesResource List of PakistanShahpoor Khan WazirNo ratings yet

- Gen 2v18-25 OTE 2010Document22 pagesGen 2v18-25 OTE 2010fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Semiotics - Vol1.No1.NazarovaDocument9 pagesSemiotics - Vol1.No1.Nazarovaradugeorge11No ratings yet

- Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A Critical Analysis of Theory and PracticeDocument68 pagesSustainable Livelihood Approach: A Critical Analysis of Theory and PracticefanzefirlNo ratings yet

- ENGL301 An Introduction To Literary Criticism and TheoryDocument3 pagesENGL301 An Introduction To Literary Criticism and Theorydinho91No ratings yet

- SemioticsDocument8 pagesSemioticsfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- SemioticsDocument8 pagesSemioticsfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics of EncounterDocument16 pagesAesthetics of EncounterfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Inclusive Agreements: Towards A Critical Discourse Theory of DemocracyDocument19 pagesThe Politics of Inclusive Agreements: Towards A Critical Discourse Theory of DemocracyfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- 978 1 4438 0499 8 SampleDocument30 pages978 1 4438 0499 8 SamplefanzefirlNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document26 pagesCH 1fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Guide For Legislators 3.30.15Document13 pagesGuide For Legislators 3.30.15fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- 2011-12 Skakov - Ekphrastic Metaphysics of Dzhan - UlbandusDocument17 pages2011-12 Skakov - Ekphrastic Metaphysics of Dzhan - UlbandusfanzefirlNo ratings yet

- NLR 30302Document3 pagesNLR 30302fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- Kaminskij 231509Document15 pagesKaminskij 231509fanzefirlNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Παπάδειγμα in Plato's Theory of Forms - William J. Prior PDFDocument10 pagesThe Concept of Παπάδειγμα in Plato's Theory of Forms - William J. Prior PDFPricopi VictorNo ratings yet

- Asian Cuisine SEMIS ExamDocument8 pagesAsian Cuisine SEMIS ExamJohn Marc LomibaoNo ratings yet

- Computer Science 9618: Support For Cambridge International AS & A LevelDocument2 pagesComputer Science 9618: Support For Cambridge International AS & A Levelezzeddinezahra_55049No ratings yet

- Wayne Wright PowerPointDocument176 pagesWayne Wright PowerPointCamila Veilchen Oliveira75% (4)

- Ps Asia Catalogue 6 (Jan 2021) (Free)Document120 pagesPs Asia Catalogue 6 (Jan 2021) (Free)Muhammad DanaNo ratings yet

- Resume SampleDocument3 pagesResume SampleAlibasher H. Azis EsmailNo ratings yet

- Active Citizenship - NotesDocument3 pagesActive Citizenship - NotesAhmet SerdengectiNo ratings yet

- 4 5850518413826327694Document378 pages4 5850518413826327694MOJIB0% (1)

- Accomplishment Completion Report (ACR) 2019Document9 pagesAccomplishment Completion Report (ACR) 2019catherine galve100% (1)

- BA English Honours Programme (Baegh) : BEGC - 102Document4 pagesBA English Honours Programme (Baegh) : BEGC - 102Ekta GautamNo ratings yet

- What Is EthicsDocument5 pagesWhat Is EthicshananurdinaaaNo ratings yet

- Responsible LeadershipDocument3 pagesResponsible LeadershipusmanrehmatNo ratings yet

- Schauer (1982) - Free SpeechDocument249 pagesSchauer (1982) - Free SpeechJoel Emerson Huancapaza Hilasaca100% (2)

- Certificate For Domicile of RajasthanDocument6 pagesCertificate For Domicile of RajasthanIndiaresultNo ratings yet

- Alignment Classroom Instruction Delivery PlanDocument3 pagesAlignment Classroom Instruction Delivery PlanWilly Batalao PuyaoNo ratings yet

- Dixon IlawDocument11 pagesDixon IlawKristy LeungNo ratings yet

- Learning Episode 2Document9 pagesLearning Episode 2Erna Vie ChavezNo ratings yet

- The Post New Left and ReificationDocument164 pagesThe Post New Left and ReificationJake KinzeyNo ratings yet

- Taxidermy: SpeculativeDocument340 pagesTaxidermy: SpeculativeAssem Ashraf Khidhr100% (1)

- Presentación. Tema 22 - Classroom ManagementDocument6 pagesPresentación. Tema 22 - Classroom ManagementJanine WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Singson vs. Singson (Jan 2018)Document4 pagesSingson vs. Singson (Jan 2018)Sam LeynesNo ratings yet

- Postcolonialism Nationalism in Korea PDFDocument235 pagesPostcolonialism Nationalism in Korea PDFlksaaaaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Learning Styles of Students at FCT College of Education, Zuba-Abuja Nigeria On Basic General Mathematics GSE 212Document6 pagesLearning Styles of Students at FCT College of Education, Zuba-Abuja Nigeria On Basic General Mathematics GSE 212TI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Terms From Theatre The Lively ArtDocument5 pagesGlossary of Terms From Theatre The Lively ArtPNRNo ratings yet

- SJG - DAE - Questioning Design - Preview PDFDocument25 pagesSJG - DAE - Questioning Design - Preview PDFJulián JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Oral Conversation SampleDocument2 pagesRubric For Oral Conversation SampleFernando CastroNo ratings yet

- APUSH Review Video 2 European Exploration and The Columbian Exchange Period 1 EnhancedDocument2 pagesAPUSH Review Video 2 European Exploration and The Columbian Exchange Period 1 Enhanced杨世然No ratings yet

- A Comparison of The Taino, Kalinago and MayaDocument2 pagesA Comparison of The Taino, Kalinago and MayaMilana Andrew100% (2)

- The - Model - Millionaire - PPT (2) PDFDocument5 pagesThe - Model - Millionaire - PPT (2) PDFYesha Shah100% (2)