Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unit 1: Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin

Uploaded by

TrynaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unit 1: Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin

Uploaded by

TrynaCopyright:

Available Formats

Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin

Julian K. Wheatley, MIT

UNIT 1

Ji cng zh ti, q y li t;

qin l zh xng sh y z xi.

9 level tower, begin by piling earth, 1000 mile journey begins with foot down

A tall tower begins with the foundation; a long journey begins with a single step.

Loz

Contents

1.1 Conventions

1.2 Pronunciation

1.3 Numbering and ordering

1.4 Stative Verbs

1.5 Time and tense

1.6 Pronouns

1.7 Action verbs

1.8 Conventional greetings

1.9 Greeting and taking leave

1.10 Tones

1.11 Summary

1.12 Rhymes and rhythms

Exercise 1

Exercise 2

Exercise 3

1.1 Conventions

The previous Unit on sounds and symbols provided the first steps in learning to

associate the pinyin transcription of Chinese language material with accurate

pronunciation. The task will continue as you start to learn to converse by listening to

conversational material while reading it in the pinyin script. However, in the early units,

it will be all too easy to fall back into associations based on English spelling, and so

occasionally (as in the previous overview), Chinese cited in pinyin will be followed by a

more transparent transitional spelling [placed in brackets] to alert you to the new values

of the letters, eg: mng [mahng], or hn [huhn].

In the initial units, where needed, you are provided not only with an idiomatic

English translation of Chinese material, but also, in parentheses, with a word-for-word

gloss. The latter takes you into the world of Chinese concepts and allows you to understand how meanings are composed. The following conventions are used to make the

presentation of this information clearer.

a) Parentheses (...)

Summary of conventions

enclose literal meanings, eg: Mng ma? (be+busy Q)

b) Plusses

(+)

indicate one-to-many, eg: ho be+well; nn you+POL

c) Capitals

(Q)

indicate grammatical notions, eg: Q for question; POL for

polite. In cases where there is no easy label for the notion, the

Chinese word itself is cited in capitals, with a fuller explanation to

appear later: N ne? (you NE)

Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin

Julian K. Wheatley, MIT

d) Spaces

( ) enclose words, eg: hn ho versus shfu.

e) Hyphens

( - ) used in standard pinyin transcription to link certain constituents, eg

d-y first or mma-hh so-so. In English glosses, hyphens

indicate meanings of the constituent parts of Chinese compounds,

eg: hoch (good-eat).

f) Brackets

[ ] indicate material that is obligatorily expressed in one language, not

in the other: Mng ma? Are [you] busy? Or they may enclose

notes on style or other relevant information: bng be good; super

[colloquial].

g) Angle brackets < > indicate optional material: <N> li ma? ie, either N li ma? or

Li ma?

h) Non-italic / italic: indicates turns in a conversation.

1.2 Pronunciation

To get your vocal organs ready to pronounce Chinese, it is useful to contrast the

articulatory settings of Chinese and English by pronouncing pairs of words selected for

their similarity of sound. Thus ko to test differs from English cow not only in tone,

but also in vowel quality.

a)

ko

ho

no

cho

so

bo

cow

b)

how

now

chow[-time]

sow[s ear]

[ships] bow

xn

qn

jn

xn

jn

ln

d)

p

b

m

paw

bo[r]e

mo[r]e

doo[r]

to[r]e

law

du

tu

lu

sin

chin

gin

seen

Jean

lean

c)

shu

zhu

su

ru

du

tu

show

Joe

so

row

dough

toe

e)

bzi

lzi

xzi

beads

leads

seeds

1.3 Numbering and ordering

This section contains information that can be practiced daily in class by counting off, or

giving the days date.

1.3.1

The numbers, 1 10:

y

1

r

2

sn

3

s

4

w

5

li

6

q

7

b

8

ji

9

sh

10

Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin

Julian K. Wheatley, MIT

1.3.2 Beyond 10

Higher numbers are formed quite regularly around sh ten (or a multiple of ten), with

following numbers additive (shsn 13, shq 17) and preceding numbers

multiplicative (snsh 30, qsh 70):

shy

11

shr shs

12

14

rsh

20

rshy rshr rshs snsh snshy

21

22

24

30

31

1.3.3 The ordinal numbers

Ordinals are formed with a prefix, d (which by pinyin convention, is attached to the

following number with a hyphen):

d-y

1st

d-r

2nd

d-sn d-s

3rd

4th

d-w, etc.

5th

1.3.4. Dates

Dates are presented in descending order in Chinese, with year first (nin, think [nien]),

then month (yu, think [yu-eh]) and day (ho). Years are usually presented as a string of

digits (that may include lng zero) rather than a single figure: y-ji-ji-li nin 1996;

r-lng-lng-sn nin 2003. Months are formed regularly with numerals: yyu

January, ryu February, shryu December.

rlnglngsn nin byu sn ho

yjibw nin ryu shb ho

August 3rd, 2003

February 18th, 1985

Notes

1. Amongst northern Chinese, yyu often shows the yi tone shift in combination

with a following day: yyu sn ho. Q 7 and b 8, both level-toned words,

sometimes show the same shift in dates (as well as in other contexts prior to a

fourth toned word): qyu li ho; byu ji ho.

2. In the written language, r day (a much simpler character) is often used in

place of ho: thus written byu sn r (), which can be read out as

such, would be spoken as b ~ byu sn ho (which in turn, could be written

verbatim as ).

1.3.5 The celestial stems

Just as English sometimes makes use of letters rather than numbers to indicate a sequence

of items, so Chinese sometimes makes use of a closed set of words with fixed order

known as the ten stems (shgn), or the celestial stems (tingn), for counting

purposes. The ten stems have an interesting history, which will be discussed in greater

detail along with information on the Chinese calendar in 4.6.2. For now, they will be

used in much the same way that, in English, roman numerals or letters of the alphabet are

used to mark subsections of a text, or turns in a dialogue. The first four or five of the ten

are much more frequent than the others, simply because they occur early in the sequence.

Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin

Julian K. Wheatley, MIT

The ten celestial stems (tingn)

ji

bng

dng

gng

xn

rn

gu

You might also like

- Korean Picture Dictionary: Learn 1,500 Korean Words and Phrases (Ideal for TOPIK Exam Prep; Includes Online Audio)From EverandKorean Picture Dictionary: Learn 1,500 Korean Words and Phrases (Ideal for TOPIK Exam Prep; Includes Online Audio)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- đáp án ngôn ngữ học Thầy ĐôngDocument8 pagesđáp án ngôn ngữ học Thầy ĐôngTrần Thanh SơnNo ratings yet

- 49-Sounds Write English Spellings LexiconDocument128 pages49-Sounds Write English Spellings LexiconVictoriano Torres Ribera0% (1)

- Prep Vocab Pack Ibn Jabal ArabicaDocument14 pagesPrep Vocab Pack Ibn Jabal Arabicaaldan63No ratings yet

- A Guide To Korean Characters (Hanja)Document188 pagesA Guide To Korean Characters (Hanja)SonicBunnyHop67% (3)

- (Cambridge Studies in Linguistics) Barbara Dancygier-Conditionals and Prediction - Time, Knowledge and Causation in Conditional Constructions-Cambridge University Press (1999)Document225 pages(Cambridge Studies in Linguistics) Barbara Dancygier-Conditionals and Prediction - Time, Knowledge and Causation in Conditional Constructions-Cambridge University Press (1999)Maxwell Miranda100% (1)

- EzE Ke Eqglix - IntroductionDocument6 pagesEzE Ke Eqglix - IntroductionStephen WatsonNo ratings yet

- Learning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin Julian K. Wheatley, 4/07Document22 pagesLearning Chinese: A Foundation Course in Mandarin Julian K. Wheatley, 4/07Jonas SotoNo ratings yet

- Mastering The Basic ChineseDocument4 pagesMastering The Basic ChineseMohamed Mouha YoussoufNo ratings yet

- Instructions To Students: English Course by Studying Lesson One. Follow The Instructions atDocument34 pagesInstructions To Students: English Course by Studying Lesson One. Follow The Instructions atJane-09No ratings yet

- - - newPractical Chinese Reader WORKb Volume 1 NPCR练习册第一课到第九课练习题答案Lessons 1-8)Document221 pages- - newPractical Chinese Reader WORKb Volume 1 NPCR练习册第一课到第九课练习题答案Lessons 1-8)Santé Kine Yoga-thérapieNo ratings yet

- Základní Škola, Praha 9 - Satalice, K Cihelně 137: A Comparison of Languages: Chinese and EnglishDocument10 pagesZákladní Škola, Praha 9 - Satalice, K Cihelně 137: A Comparison of Languages: Chinese and Englishqiang huangNo ratings yet

- Mid Ans PDFDocument6 pagesMid Ans PDFJoan Mae JudanNo ratings yet

- Survival Chinese: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear Instantly! (A Mandarin Chinese Language Phrasebook)From EverandSurvival Chinese: How to Communicate without Fuss or Fear Instantly! (A Mandarin Chinese Language Phrasebook)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Lesson-1 Licensed v.1.1 PDFDocument17 pagesLesson-1 Licensed v.1.1 PDFb2b121No ratings yet

- Analysis On The Korean LanguageDocument3 pagesAnalysis On The Korean LanguageLucy xNo ratings yet

- Chengsybesma 99Document34 pagesChengsybesma 99peixinlaoshiNo ratings yet

- Teach Yourself KoreanDocument19 pagesTeach Yourself KoreanKyrie Jenner100% (1)

- General Number and The Semantics and Pragmatics of Indefinite Bare Nouns in Mandarin Chinese Author Hotze Rullmann and Aili YouDocument30 pagesGeneral Number and The Semantics and Pragmatics of Indefinite Bare Nouns in Mandarin Chinese Author Hotze Rullmann and Aili YouMaite SosaNo ratings yet

- Want To Learn KoreanDocument11 pagesWant To Learn KoreanCharen Mae B. BañezNo ratings yet

- Welcome To The Vocabulary Builder Course!Document22 pagesWelcome To The Vocabulary Builder Course!Lương TrầnNo ratings yet

- Articles) .However, We Cannot Move The Articles To The End of The Sentence: He Read Today TheDocument4 pagesArticles) .However, We Cannot Move The Articles To The End of The Sentence: He Read Today ThemostarjelicaNo ratings yet

- MidSem Answer Key 2017Document4 pagesMidSem Answer Key 2017Rishabh JainNo ratings yet

- Articulators Above The LarynxDocument23 pagesArticulators Above The LarynxHilmiNo ratings yet

- HowtoStudyKorean Unit 0 PDFDocument19 pagesHowtoStudyKorean Unit 0 PDFNguyenVinhPhuc100% (1)

- Teach PhonicsDocument14 pagesTeach PhonicsoanadraganNo ratings yet

- Oh Nothing!!!!!!!!Document64 pagesOh Nothing!!!!!!!!noamflam000No ratings yet

- Unit 0 PDFDocument19 pagesUnit 0 PDFDivine SilverriaNo ratings yet

- MITRES 21F 003S11 Pinyin PDFDocument19 pagesMITRES 21F 003S11 Pinyin PDFAli AbbasNo ratings yet

- Comparative Grammar ENGLISH AND CHINESEDocument93 pagesComparative Grammar ENGLISH AND CHINESESathyamoorthy Venkatesh100% (1)

- VocabularyDocument7 pagesVocabularyRicalyn FloresNo ratings yet

- Learn To Read Korean in 60 Minutes by Blake MinerDocument46 pagesLearn To Read Korean in 60 Minutes by Blake MinerSafeer Ahmad100% (1)

- Korean in a Hurry: A Quick Approach to Spoken KoreanFrom EverandKorean in a Hurry: A Quick Approach to Spoken KoreanRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Hobby Korean Book EnglishDocument21 pagesHobby Korean Book EnglishAritra KunduNo ratings yet

- How Do Philippine Languages WorkDocument41 pagesHow Do Philippine Languages WorkChem R. PantorillaNo ratings yet

- Chp.10 Syllable Complexity (M Naveed)Document7 pagesChp.10 Syllable Complexity (M Naveed)Saif Ur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Korean LessonsDocument36 pagesKorean LessonsAsma' Haris100% (2)

- The SyllableDocument6 pagesThe SyllableTorres Ken Robin DeldaNo ratings yet

- Babcock 1 0001Document33 pagesBabcock 1 0001sprcrinklesNo ratings yet

- Korean Lessons: Day 1 (2011. 6. 13.) : 1. Fundamental Features of Korean LanguageDocument12 pagesKorean Lessons: Day 1 (2011. 6. 13.) : 1. Fundamental Features of Korean Languageanonym240No ratings yet

- Answer 1Document3 pagesAnswer 1Nishant KumarNo ratings yet

- Origins (Hasta Antes de Vowel Change)Document31 pagesOrigins (Hasta Antes de Vowel Change)Jose AGNo ratings yet

- Korean Picture Dictionary Learn 1,500 Korean Words and Phrases - Ideal For TOPIK Exam PrepDocument85 pagesKorean Picture Dictionary Learn 1,500 Korean Words and Phrases - Ideal For TOPIK Exam PrepGhost Little100% (1)

- Grammatical Categories and Functions 02cDocument10 pagesGrammatical Categories and Functions 02cAntonija StojčevićNo ratings yet

- Report Lecturer: English Phonology Evi Kasyulita, M.PDDocument11 pagesReport Lecturer: English Phonology Evi Kasyulita, M.PDDewi Prasetiya NingrumNo ratings yet

- Jyutping Pronunciation GuideDocument3 pagesJyutping Pronunciation GuideKarelBRGNo ratings yet

- Periplus Pocket Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese-English English-Cantonese (Fully Revised & Expanded, Fully Romanized)From EverandPeriplus Pocket Cantonese Dictionary: Cantonese-English English-Cantonese (Fully Revised & Expanded, Fully Romanized)No ratings yet

- Korean Lessons: Lesson 1: Fundamental Features of Korean LanguageDocument34 pagesKorean Lessons: Lesson 1: Fundamental Features of Korean LanguageYi_Mei__3165No ratings yet

- WedeiDocument23 pagesWedeiBrendan AndersonNo ratings yet

- Kenstowicz2006 2Document29 pagesKenstowicz2006 2Viet CaoNo ratings yet

- A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa TibetanDocument274 pagesA Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetanexpugsbooks100% (1)

- Essential Korean Phrasebook & Dictionary: Speak Korean with Confidence!From EverandEssential Korean Phrasebook & Dictionary: Speak Korean with Confidence!Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Mandarin IntroductionDocument9 pagesMandarin IntroductionservantkemerutNo ratings yet

- MSG Syntax SectionDocument34 pagesMSG Syntax Sectionmobeen ilyasNo ratings yet

- Phonetic Symbol: Lecturer: Drs. Muhammad. Nur, M.HumDocument12 pagesPhonetic Symbol: Lecturer: Drs. Muhammad. Nur, M.Humruly joan100% (1)

- Word Formation Presentation HandoutDocument10 pagesWord Formation Presentation HandoutBernard M. PaderesNo ratings yet

- CPE Gramatica Practica 2015-2016Document24 pagesCPE Gramatica Practica 2015-2016Marya Fanta C Lupu100% (1)

- Korean VocabularyPhrases Korean Picture Dictionary Learn 1500 Korean Words and Phrases Ideal For TOPIK Exam Prep PDFDrive - Com 20201104 133653Document85 pagesKorean VocabularyPhrases Korean Picture Dictionary Learn 1500 Korean Words and Phrases Ideal For TOPIK Exam Prep PDFDrive - Com 20201104 133653Iris Claire Hugo100% (2)

- Law2006 Article AdverbsInA-not-AQuestionsInMan PDFDocument40 pagesLaw2006 Article AdverbsInA-not-AQuestionsInMan PDFZuriñe Frías CobiánNo ratings yet

- Act2 - PRESENT PERFECT EXERCISESDocument1 pageAct2 - PRESENT PERFECT EXERCISESJesús Alexander MejíazNo ratings yet

- 1 Bac Reading Comprehension FootwearDocument5 pages1 Bac Reading Comprehension FootwearKhalil MesrarNo ratings yet

- Present Simple - Preposition of TimeDocument11 pagesPresent Simple - Preposition of TimeLilasNo ratings yet

- Compound NounsDocument8 pagesCompound NounsREDDTOTAL ACAYUCANNo ratings yet

- Dang Dai 1 15-17Document3 pagesDang Dai 1 15-17Febe AgungNo ratings yet

- Reading and Use of English Part 5 (Multiple Choice)Document1 pageReading and Use of English Part 5 (Multiple Choice)harifiNo ratings yet

- Extended Irregular Verbs ListDocument25 pagesExtended Irregular Verbs ListminsandiNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 - Personal Stories - Language SummaryDocument1 pageUnit 2 - Personal Stories - Language Summarythao0505No ratings yet

- Techical Institute Private of HealthDocument2 pagesTechical Institute Private of HealthAdilson Barbosa AvbNo ratings yet

- LEXICOLOGY I - Lectures: Lecture 1 - IntroductionDocument80 pagesLEXICOLOGY I - Lectures: Lecture 1 - IntroductionPavla JanouškováNo ratings yet

- Mini Glosar Gramatica EnglezaDocument11 pagesMini Glosar Gramatica EnglezaGeorgianaClementineNo ratings yet

- Grammar - Present Progressive Positive - Negative - Revisión Del IntentoDocument3 pagesGrammar - Present Progressive Positive - Negative - Revisión Del Intentogoku gokuNo ratings yet

- Nouns - Nationalities: See AdjectivesDocument5 pagesNouns - Nationalities: See AdjectivesLutfan LaNo ratings yet

- Examples of Adjective ComplementsDocument3 pagesExamples of Adjective ComplementsKhristine Joyce A. Reniva100% (1)

- Reported Speech vs. Quotations PracticeDocument1 pageReported Speech vs. Quotations PracticellsrNo ratings yet

- The 101 Translation Problems Between Japanese and German/EnglishDocument49 pagesThe 101 Translation Problems Between Japanese and German/EnglishTatiana PozdnyakovaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2-Simple Present TenseDocument12 pagesChapter 2-Simple Present TenseFathina IffatunnisaNo ratings yet

- Karaka Prakaranam EnglishDocument120 pagesKaraka Prakaranam EnglishGm Rajesh29100% (1)

- English 9Document17 pagesEnglish 9Joann Gaan YanocNo ratings yet

- Direct Pronouns: The in Italian AreDocument2 pagesDirect Pronouns: The in Italian AreFederica MarrasNo ratings yet

- Grade 1 Annual Syllabus 1920Document2 pagesGrade 1 Annual Syllabus 1920Sanket ShahNo ratings yet

- 0 Test PredictivviithDocument3 pages0 Test PredictivviithmirabikaNo ratings yet

- Reading Vocabulary: Word ListDocument15 pagesReading Vocabulary: Word ListKIM호띠No ratings yet

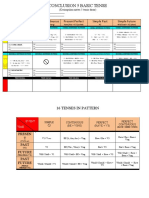

- Conclusion 5 Basic Tense: Simple Present Present Continuous Present Perfect Simple Past Simple FutureDocument2 pagesConclusion 5 Basic Tense: Simple Present Present Continuous Present Perfect Simple Past Simple FutureAdila Faila CassiopeiaNo ratings yet

- City Lit - Parts of Speech - AdverbsDocument4 pagesCity Lit - Parts of Speech - AdverbsGerry ParkinsonNo ratings yet

- Is Harry Potter Written in EnglishDocument3 pagesIs Harry Potter Written in EnglisheduNo ratings yet

- IELTS Grammar ExerciseDocument5 pagesIELTS Grammar ExerciseХиба Ю100% (1)

- Punctuation & CapitalizationDocument16 pagesPunctuation & CapitalizationPaul FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Clauses in English Grammar With Examples PDFDocument6 pagesClauses in English Grammar With Examples PDFhemisphereph2981No ratings yet