Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Smiling After Thinking Increases Reliance On Thoughts

Uploaded by

Yani ZoiloOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Smiling After Thinking Increases Reliance On Thoughts

Uploaded by

Yani ZoiloCopyright:

Available Formats

Authors personal copy (e-offprint)

B. Paredes et al.: Smiling

2012

Social

Validates

Hogrefe

Psychology

Tho

Publishing

ughts

2012

Original Article

Smiling After Thinking Increases

Reliance on Thoughts

Borja Paredes1, Maria Stavraki2, Pablo Briol1,2, and Richard E. Petty3

1

Universidad Autnoma de Madrid, Spain, 2Universidad A Distancia de Madrid, Spain,

3

Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Abstract. The present research examines the impact of smiling on attitude change. Participants were first exposed to a story that elicited

mostly positive thoughts (about an employees good day at work) or negative thoughts (about an employees bad day at work). After

writing down their thoughts, participants were asked to hold a pen with their teeth (smile) or with their lips (control). Finally, all participants reported the extent to which they liked the story. In line with the self-validation hypothesis, we predicted and found that the effect

of the initial thought direction induction on story evaluations was greater for smiling than control participants. These results conceptually

replicate those obtained in previous research on embodiment (i.e., more favorable evaluations of stories when smiling; Strack, Martin,

& Stepper, 1988) when participants had positive thoughts, but showed the opposite pattern of results (less favorable evaluations for

smiling) for negative thoughts.

Keywords: attitudes, emotion, validation, embodiment

Smiling is a positive behavior that often leads to positive

evaluations. In a classic study, Strack, Martin, and Stepper

(1988) asked participants either to hold a pen between their

teeth (facilitating a facial pose similar to smiling) or to hold

a pen between their lips (inhibiting the facial muscles involved in smiling) while watching cartoons. Although participants did not recognize the meaning of their facial pose,

they judged cartoons to be funnier when smiling than in the

inhibition condition.

The finding that people might like something more when

they are smiling has been interpreted as a case in which

people use simple heuristics (e.g., if I am smiling, I must

like it; Bem, 1972; Laird & Bresler, 1992), or generate (positive) thoughts that are compatible with smiling (Frster &

Strack, 1996; Neumann, Frster, & Strack, 2003). Indeed,

there are several different processes by which bodily responses such as a smile can influence attitudes (Briol &

Petty, 2008). In the current research, we argue that smiling

can also influence validation processes.

Recently, it was proposed that overt behavior cannot only influence the content of thoughts, but can also impact

what people think about their thoughts (Briol & Petty,

2003). This is important because both the content of

thoughts and an assessment of those thoughts contribute to

the judgments formed (Petty, Briol, & Tormala, 2002).

This idea, called embodied validation (Briol, Petty, &

Wagner, 2012), suggests that the appraisals that emerge

from ones body can determine the impact of anything that

is currently available in peoples minds. The notion that

2012 Hogrefe Publishing

smiling can affect reliance on thoughts stems from the finding that emotional states (potentially induced by smiling)

can relate to two different appraisals.

First, happiness leads people to feel more confident than

a sad or neutral state (Smith & Ellsworth, 1985; Tiedens &

Linton, 2001). If this confidence is applied to ones

thoughts, it would lead to greater use of those thoughts

(cognitive validation). Thus, if smiling makes people happy, they should be more reliant on their thoughts if thinking

is followed by a smile than a neutral expression. Second, a

happy face can lead people to feel more pleasant than a sad

or neutral state. If this feeling of pleasantness is applied to

ones thoughts (e.g., I like my thoughts), it would also lead

to greater use of those thoughts (affective validation). Taken together, these two appraisals of happiness (i.e., confidence and pleasantness) suggest that smiling can lead to

greater reliance on thoughts because, when smiling, people

think that their thoughts are more valid and/or because they

like them more.

Consistent with the idea that happiness can increase reliance on thoughts, Briol, Petty, and Barden (2007) found

that when individuals wrote happy memories following

message processing, attitudes were more influenced by the

recipients thoughts about the arguments than when they

wrote about sad memories following the message (see also

Clore & Huntsinger, 2007; Huntsinger & Clore, 2012). Although this research was carried out to examine the impact

of persuasive messages in the domain of attitude change, it

provides converging evidence that the impact of inductions

Social Psychology 2012

DOI: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000131

Authors personal copy (e-offprint)

B. Paredes et al.: Smiling Validates Thoughts

of emotional states on judgments can operate by validation

processes.

What remains to be examined is whether the embodiedvalidation logic can be applied to the impact of smiling

(rather than verbal inductions). In order to test this possibility, the present study exposed participants to a story that

described an employees good or bad day at work, designed

to produce mostly positive or negative thoughts, respectively. After writing down their thoughts about the story,

participants were asked to hold a pen with their teeth

(smile) or with their lips (control). It was expected that

smiling would be associated with greater reliance on

thoughts than nonsmiling informing evaluations about the

story.

Method

Participants and Design

Sixty-two undergraduates at the Universidad Autnoma de

Madrid, Spain, were randomly assigned to a 2 (Employee

Story: good day vs. bad day) 2 (Facial Pose: smile vs.

control) between-subjects factorial design.

Procedure

Participants were induced to believe that they were going

to be involved in two different research projects. The first

study was described as related to organizational behavior

and the second one was presented as related to psychomotor coordination. For the first project, participants

were asked to read a prototypical situation of an employee. They read a description about a good or bad day of

that employee at work. After reading the story, participants were asked to write down the thoughts they had

with respect to the story they had just read. Next, in an

ostensibly unrelated study on psychomotor coordination,

the overt behavior manipulation was induced. Specifically, participants in the smile condition were asked to hold

a pen with their teeth, whereas those in the control condition were instructed to hold a pen with their lips. Finally, all participants evaluated the story, completed some

ancillary measures, and were debriefed, thanked, and dismissed.

Independent Variables

end of this day, the person received a fair promotion for

his merits. In contrast, in the negative employee story,

participants read about an employee being late for an important meeting, not knowing what to do during that

meeting, and crying as a coping mechanism. At the end

of the story the employee was fairly fired for his incompetence. The stories were designed and pretested to induce mostly positive thoughts and feelings (in response

to the good day at work) and negative thoughts and feelings (in response to the bad day at work).

Facial Pose

Participants facial poses were manipulated following the

classic induction by Strack et al. (1988). Specifically,

half of the participants were instructed to hold a pen with

their lips (control), and half of them were instructed to

hold it with their teeth (smile). As part of the cover story

for this induction, students were led to believe that they

were participating in a psychomotor coordination pilot

test designed to assess peoples ability to perform various

tasks with their bodies. Before holding the pen, participants were told to disinfect it with the alcohol swab provided. Importantly, the words smile, happy, laugh,

or frown were never mentioned in the instructions, thus

reducing the possibility of semantic priming. Although

subtle, this procedure has been shown to be an effective

and reliable way to induce smiles in the laboratory (Effron, Niedenthal, Gil, & Droit-Volet, 2006; Niedenthal,

2007; Soussignan, 2002).

Dependent Measures

Thought Listing

Participants were instructed to list the thoughts and feelings that they had as they read the story. Ten boxes were

provided. They were told to write one thought per box

and not to worry about grammar or spelling (see Cacioppo & Petty, 1981, for additional details on the thought

listing procedure). At the end of the experiment, participants were again presented with the thoughts they had

written and asked to rate them as positive, neutral, or

negative toward the story. An index of the valence of story-related thoughts was created for each participant by

subtracting the number of unfavorable thoughts from the

number of favorable thoughts that he or she had listed.

This difference score was then divided by the total number of message-related thoughts.

Employee Story

Participants read a story about a persons good or bad day

at work. In the positive version of the story, the employee

was described as successfully leading an important meeting and being congratulated by his peers and boss. At the

Social Psychology 2012

Attitudes

Participants were asked to evaluate the story using a series of three 9-point (19) semantic differential scales

2012 Hogrefe Publishing

Authors personal copy (e-offprint)

B. Paredes et al.: Smiling Validates Thoughts

(likedont like, very interestingnot at all interesting,

positivenegative). Ratings on these items were highly

intercorrelated ( = .85), so they were averaged to form

one overall attitude index. Higher values on this index

indicated more liking of the story.

Ancillary Measures

After evaluating the story, participants were asked to complete a number of 9-point scales, asking for perceived

amount of thinking, attention paid to the story, personal

relevance of the study, level of accuracy with which the

questionnaire was completed, and difficulty associated

while holding the pen. Finally, two independent judges

scored the number of ideas per thought written by the students in the thought listing task.

Results

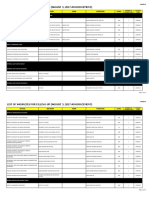

Figure 1. Attitudes as a function of employee story and

facial pose.

Thought Listing

A 2 (Employee Story: good day vs. bad day) 2 (Facial

Pose: smile vs. control) ANOVA conducted on participants thoughts revealed a main effect of Employee Story,

F(1, 58) = 22.55, p < .001. As predicted, participants rated

their thoughts to be more positive after reading the good

day story (M = 0.15, SD = 0.51) than after reading the bad

day story (M = 0.43, SD = 0.48). No other main effect or

interaction emerged, ps > .15.

Attitudes

The 2 2 ANOVA revealed a main effect for Employee

Story such that participants liked the story about a good day

more (M = 6.90, SD = 1.32) than the story about a bad day

(M = 3.70, SD = 1.32) at work, F(1, 58) = 99.95, p < .001.

More critical to our primary concerns, the predicted twoway interaction between Employee Story and Facial Pose

was significant, F(1, 58) = 9.76, p = .003.1 As illustrated in

Figure 1, for smiling participants, those who received the

good-day story reported significantly more favorable attitudes (M = 7.42, SD = 1.22) than did those who received

the bad-day story (M = 3.23, SD = 1.16), F(1, 58) = 76.24,

p < .001. For control participants, those reading the goodday story also reported liking it more (M = 6.37, SD = 1.24)

1

than those reading about the bad-day story (M = 4.17, SD

= 1.33), F(1, 58) = 27.12, p < .001, although this difference

was smaller compared to the smiling participants.

To put it differently, in the story describing a good day

at work, participants in the smile condition reported significantly more favorable attitudes toward the story (M =

7.43, SD = 1.22) than did those in the control condition,

(M = 6.38, SD = 1.25) F(1, 58) = 5.61, p = .021. In contrast, for the bad-day story, participants in the smiling

condition liked the story less (M = 3.23, SD = 1.16) than

did those in the control condition (M = 4.17, SD = 1.33),

F(1, 58) = 4.23, p = .044.2

Ancillary Measures

No main or interaction effects emerged for any of the

other items (i.e., attention, concentration, personal relevance, accuracy, amount of thinking, and difficulty), ps

> .16. As an additional control measure, the number of

different ideas embedded in the thoughts listed by participants were coded by two judges (kappa index = .612).

No differences across conditions were found for this index suggesting that all participants listed a similar number of ideas per thought.

To check whether emotions induced by the story were also validated as well as cognitions, participants were asked to report how good/bad

the story made them feel on a nine-point scale (1 = bad, 9 = good). This item was highly correlated with the attitude index (r = .82, p <

.001), and the 2 2 ANOVA revealed a similar significant 2-way interaction when analyzed, F(1, 58) = 6.48, p = .014.

We also examined whether there was a stronger relationship between thoughts and attitudes for smiling than control conditions. Regressing

attitudes onto the relevant variables, a significant interaction emerged between the thought-favorability index and the facial expression

condition, B = 1.702, t(61) = 2.180, p = .033. Consistent with the self-validation logic, this interaction revealed that participants thoughts

exerted a stronger effect on attitudes when smiling (B = 2.547, t(26) = 4.293, p < .001) than when in a control pose (B = 0.845, t(34) =

1.630, p > .11).

2012 Hogrefe Publishing

Social Psychology 2012

Authors personal copy (e-offprint)

B. Paredes et al.: Smiling Validates Thoughts

Discussion

This experiment revealed that the effect of the direction of

participants thoughts on attitudes was greater when participants were made to smile following thought generation

than when they were made to hold a control pose. Thus,

participants with a smiling expression relied more on their

thoughts in forming their attitudes than did control participants. These results conceptually replicate those obtained

in previous research (more favorable evaluations of stories

when smiling than nonsmiling, Strack et al., 1988) but

only when participants had positive thoughts. An opposite

pattern of results (more favorable evaluations for frowning

than smiling) was found for negative thoughts.

Although speculative, the present study suggests that facial poses can validate what people think. One possible alternative interpretation is that smiling affected the amount

of thinking by increasing elaboration of the story. For example, according to the hedonic contingency view (Wegener, Petty, & Smith, 1995), if participants thought that the

story was going to make them happy, smiling might have

led participants to pay more attention relative to control.

Also, smiling might induce more thinking because smiling

might indicate that thinking continues to be enjoyable

(Martin, Ward, Achee, & Wyer, 1993), or because smiling

might have led people to make more connections among

and between their thoughts (Fredrickson & Branigan,

2005). We argue that a change in the amount of thinking is

not likely to explain the obtained results for a number of

reasons. First, in the present study, we created a context of

high likelihood of elaboration in order to elicit enough motivation for people to think. Second, the induction of facial

poses followed (rather than preceded) the processing of the

story, making it unlikely that the thoughts generated in response to the stories were affected by something that did

not take place until later. In fact, participants listed the same

number and direction of thoughts and reported similar

scores of subjective effort across conditions. Furthermore,

external judges did not find more ideas listed in one condition than another. Finally, although smiling might be capable of increasing thinking over control facial poses under

certain conditions (not present in the current study), most

of the previous research has shown that, if anything, the

opposite pattern of results is more likely to emerge (Bless,

Bhner, Schwarz, & Strack, 1990; Mackie & Worth, 1989;

Schwarz, Bless, & Bohner, 1991; Schwarz & Clore, 1983;

Tiedens & Linton, 2001).

In closing, it is important to note the potential real-life

situations in which smiling occurs following thinking. For

example, we might validate or invalidate the thoughts of

others by smiling following their comments. Consistent

with this reasoning, Stepper and Strack (1993) found that,

when people recalled behaviors of self-assurance when

smiling rather than nonsmiling, they felt more self-assured,

but when they recalled behaviors of low self-assurance,

they felt less self-assured when smiling than when nonsmilSocial Psychology 2012

ing. The self-validation framework provides an explanation for those findings according to which smiling enhanced reliance on the current mind content.

Of course, for smiling to enhance reliance on the contents of a persons mind, it requires the smile to be perceived as a positive and authentic behavioral cue. If smiling

is associated with feelings of embarrassment (Keltner &

Anderson, 2000), faking (non-Duchenne; Ekman, Davidson, & Friesen, 1990), or with trivialization (Martinie &

Fointiat, 2006; Simon, Greenberg & Brehm, 1995), then it

might reduce the impact of thoughts relative to control.

People and contexts can also vary in other relevant variables, such as the extent to which people attend to and use

their behavior in defining their attitudes (Dunn et al., 2010).

References

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.),

Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 162).

New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bless, H., Bhner, G., Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1990). Mood

and persuasion: A cognitive response analysis. Personality

and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 331345.

Briol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2003). Overt head movements and persuasion: A self-validation analysis. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 84, 11231139.

Briol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2008). Embodied persuasion: Fundamental processes by which bodily responses can impact attitudes. In G. R. Semin, & E. R. Smith (Eds.), Embodiment

grounding: Social, cognitive, affective, and neuroscientific approaches (pp. 184208). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Briol, P., Petty, R. E., & Barden, J. (2007). Happiness versus

sadness as determinants of thought confidence in persuasion:

A self-validation analysis. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 93, 711727.

Briol, P., Petty, R. E., & Wagner, B. C. (2012). Embodied validation: Our body can change and also validate our thoughts.

In P. Briol & K. G. DeMarree (Eds.), Social metacognition

(pp. 219240). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1981). Social psychological procedures for cognitive response assessment: The thought listing

technique. In T. Merluzzi, C. Glass, & M. Genest (Eds.), Cognitive assessment (pp. 309342). New York, NY: Guilford.

Clore, G. L., & Huntsinger, J. R. (2007). How emotions inform

judgment and regulate thought. Trends in Cognitive Sciences,

11, 393399.

Dunn, B. D., Galton, H. C., Morgan, R., Evans, D., Oiver, C.,

Meyer, M., & Dalgleish, T. (2010). Listening to your heart:

How interception shapes emotion experience and intuitive decision making. Psychological Science, 21, 18351844.

Effron, D. A., Niedenthal, P. M., Gil, S., & Droit-Volet, S. (2006).

Embodied temporal perception of emotion. Emotion, 6, 19.

Ekman, P., Davidson, R. J., & Friesen, W. V. (1990). The Duchenne smile: Emotional expression and brain physiology II.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 342353.

Frster, J., & Strack, F. (1996). The influence of overt head movements on memory for valenced words: A case of conceptual 2012 Hogrefe Publishing

Authors personal copy (e-offprint)

B. Paredes et al.: Smiling Validates Thoughts

motor compatibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 421430.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005) Positive emotions

broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires.

Cognition and Emotion, 19, 313332.

Huntsinger, J. R., & Clore, G. L. (2012). Emotion and meta-cognition. In P. Briol & K. DeMarree (Eds.), Social meta-cognition (pp. 199218). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Keltner, D., & Anderson, C. (2000). Saving face for Darwin: The

functions and uses of embarrassment. Current Directions in

Psychological Science, 9(6), 187192.

Laird, J. D., & Bresler, C. (1992). The process of emotional experience: A self-perception theory. In M. S. Clard (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology (pp. 213234).

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mackie, D. M., & Worth, L. T. (1989). Cognitive deficits and the

mediation of positive affect in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 2740.

Martin, L. L., Ward, D. W., Achee, J. W., & Wyer, R. S. (1993).

Mood as input: People have to interpret the motivational implications of their moods. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 64, 317326.

Martinie, M. A., & Fointiat, V. (2006). Self-esteem, trivialization,

and attitude change. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 65, 221225.

Neumann, R., Frster, J., & Strack, F. (2003). Motor compatibility: The bi-directional link between behavior and evaluation.

In J. Musch & K. C. Klauer (Eds.), The psychology of evaluation: Affective processes in cognition and emotion

(pp. 371391). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). Embodying emotion. Science, 316,

10021005.

Petty, R. E., Briol, P., & Tormala, Z. L. (2002). Thought confidence

as a determinant of persuasion: The self-validation hypothesis.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 722741.

Schwarz, N., Bless, H., & Bohner, G. (1991). Mood and persuasion: Affective status influence the processing of persuasive

communications. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental

social psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 161197). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and

judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions

2012 Hogrefe Publishing

of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 513523.

Simon, L., Greenberg, J., & Brehm, J. (1995). Trivialization: The

forgotten mode of dissonance reduction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 247260.

Smith, C. A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 813838.

Soussignan, R. (2002). Duchenne smile, emotional experience,

and autonomic reactivity: A test of the facial feedback hypothesis. Emotion, 2, 5274.

Stepper, S., & Strack, F. (1993). Proprioceptive determinants of

emotional and nonemotional feelings. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 64, 211220.

Strack, F., Martin, L., & Stepper, S. (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smile: A nonobtrusive test of

the facial feedback hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 768777.

Tiedens, L. Z., & Linton, S. (2001). Judgment under emotional

certainty and uncertainty: The effects of specific emotions on

information processing. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 81, 973988.

Wegener, D. T., Petty, R. E., & Smith, S. M. (1995). Positive mood

can increase or decrease message scrutiny: The hedonic contingency view of mood and message processing. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 515.

Received May 15, 2012

Final revision received September 12, 2012

Accepted September 13, 2012

Published online December 11, 2012

Pablo Briol

Department of Psychology

Universidad Autnoma de Madrid

Campus de Cantoblanco (Crta. Colmenar, Km. 15)

28049 Madrid

Spain

E-mail pablo.brinnol@uam.es

Social Psychology 2012

You might also like

- Journal Artricle Reading AnswersDocument3 pagesJournal Artricle Reading AnswersKelyn GouveiaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Jatin PawarDocument4 pagesAssignment 2 Jatin PawarJatin PawarNo ratings yet

- Draw - A - Person - TestDocument21 pagesDraw - A - Person - TestSandy75% (4)

- BBRC4103 Research MethodologyDocument23 pagesBBRC4103 Research MethodologyPAPPASSINI100% (1)

- Lbs 302 Classroom Management PlanDocument10 pagesLbs 302 Classroom Management Planapi-437553094No ratings yet

- Organizational Behaviour Cia-01Document4 pagesOrganizational Behaviour Cia-01Kumar Pritam MehtaNo ratings yet

- Sample Reaction PaperDocument3 pagesSample Reaction PaperAnonymous Gi063kNo ratings yet

- Sample Semi Detailed OBE Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesSample Semi Detailed OBE Lesson PlanJude Salayo OaneNo ratings yet

- The Falsification of Black ConsciousnessDocument14 pagesThe Falsification of Black ConsciousnessEon G. Cooper94% (16)

- Chapter 2 and 3Document8 pagesChapter 2 and 3Faith GracielleNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesLiterature ReviewOluwasanmi AkinbadeNo ratings yet

- Experiment Proposal: Do We Need Both Empathy and Episodic Memory To Enjoy Humor Better?Document8 pagesExperiment Proposal: Do We Need Both Empathy and Episodic Memory To Enjoy Humor Better?Anggun Citra BerlianNo ratings yet

- Effect of Consumers Mood On Advertising EffectivenessDocument10 pagesEffect of Consumers Mood On Advertising EffectivenessAzilmi Lukmanul HakimNo ratings yet

- Gender & Mood Effects On GenderDocument25 pagesGender & Mood Effects On GenderNikita HuddartNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Theory of Mind 2Document15 pagesResearch Paper Theory of Mind 2api-529331295No ratings yet

- Emotional Labour DissertationDocument4 pagesEmotional Labour DissertationCollegePaperWritersUK100% (1)

- Week 8 Sample Student Quantitative Report B - AccessibleDocument10 pagesWeek 8 Sample Student Quantitative Report B - AccessibleModerkayNo ratings yet

- SupplementaryMaterial R2defDocument4 pagesSupplementaryMaterial R2defDiegoMoraTorresNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence PaperDocument16 pagesEmotional Intelligence PaperAnthony Thomas100% (1)

- Projective DrawingsDocument14 pagesProjective DrawingsLeya CallantaNo ratings yet

- Keep SmilingDocument11 pagesKeep SmilingmirrejNo ratings yet

- The Dimensions of Positive Emotions: Michael Argyle and Jill CrosslandDocument11 pagesThe Dimensions of Positive Emotions: Michael Argyle and Jill CrosslandDwi Ajeng PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Semantic Measures Using Natural Language Processing To MeasureDocument85 pagesSemantic Measures Using Natural Language Processing To MeasureAracelliNo ratings yet

- The Place of Humor in The ClassroomDocument19 pagesThe Place of Humor in The Classroomkirill1017No ratings yet

- 6 2023 1005 Projective IQRMDocument17 pages6 2023 1005 Projective IQRMRohit KumarNo ratings yet

- Inglés Científico para Psicología (Unit 1)Document11 pagesInglés Científico para Psicología (Unit 1)Sonsoles BarciaNo ratings yet

- Openness To Experience, Extraversion, and Subjective Well-Being Among Chinese College Students The Mediating Role of Dispositional AweDocument26 pagesOpenness To Experience, Extraversion, and Subjective Well-Being Among Chinese College Students The Mediating Role of Dispositional AweGeorges El NajjarNo ratings yet

- Definition of TermsDocument3 pagesDefinition of TermsChristia Lyne SarenNo ratings yet

- A Dynamic Perspective On Affect and CreativityDocument8 pagesA Dynamic Perspective On Affect and CreativityJohn OMalleyNo ratings yet

- Humor Styles and Emotional IntelligenceDocument55 pagesHumor Styles and Emotional IntelligenceMendoza Jacky LynNo ratings yet

- Together: The Science of Social PsychologyDocument5 pagesTogether: The Science of Social PsychologyDulce ChavezLNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument23 pagesLiterature Reviewdoaa shafieNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence ActivitieDocument48 pagesEmotional Intelligence ActivitieHarshpreet BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Psychodynamic PerspectiveDocument7 pagesPsychodynamic Perspectivem.palattao74No ratings yet

- Life Satisfaction of Employees in Terms of Gender and Age: Research ArticleDocument8 pagesLife Satisfaction of Employees in Terms of Gender and Age: Research Articlekaipulla1234567No ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature Emotional IntelligenceDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature Emotional Intelligenceea7gpeqmNo ratings yet

- Dual Code Theory - Abstract or Concrete WordsDocument18 pagesDual Code Theory - Abstract or Concrete Wordshunarsandhu100% (1)

- Marrero2019 Article DoesHumorMediateTheRelationshiDocument28 pagesMarrero2019 Article DoesHumorMediateTheRelationshiKiyoshi Hideki Naito VegaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Evaluation Theory of Motivation (CET)Document8 pagesCognitive Evaluation Theory of Motivation (CET)DaniyaShafiqNo ratings yet

- Relationship-Between-Happiness-and-Resilience-Among-2nd-Year-AB-Psychology-Students-Of-SBIS 2Document24 pagesRelationship-Between-Happiness-and-Resilience-Among-2nd-Year-AB-Psychology-Students-Of-SBIS 2Althea Mari PrescillaNo ratings yet

- EAPP Position-Paper-PersuasiveDocument4 pagesEAPP Position-Paper-PersuasiveJoy Prestoza CaraganNo ratings yet

- 7 - Creativity and Happiness in University StudentsDocument8 pages7 - Creativity and Happiness in University StudentskimberlytaconersNo ratings yet

- Case Study Emotional Inteligence and Its Affect On Performance & Engagement. Bba+Mba (2012-2016)Document11 pagesCase Study Emotional Inteligence and Its Affect On Performance & Engagement. Bba+Mba (2012-2016)MayankTayal100% (1)

- BLM - PreprintDocument50 pagesBLM - PreprintCake PanNo ratings yet

- 2001 Humor HumorasCopingDocument20 pages2001 Humor HumorasCopingYanti HarjonoNo ratings yet

- The Roles of Emotion in Consumer ResearchDocument9 pagesThe Roles of Emotion in Consumer Researchm_taufiqhidayat489No ratings yet

- tmpC3A2 TMPDocument8 pagestmpC3A2 TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Project Report 3rd DraftDocument11 pagesProject Report 3rd DraftSaisha SinghNo ratings yet

- Diazgranados Et Al-2015-Social DevelopmentDocument30 pagesDiazgranados Et Al-2015-Social DevelopmentJuan EstebanNo ratings yet

- Coun79 Group Session DesignDocument17 pagesCoun79 Group Session Designapi-251685362No ratings yet

- The Affective Resonance Processes in Creative WritingDocument13 pagesThe Affective Resonance Processes in Creative WritingMartin SosaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Final Out PutDocument7 pagesChapter 2 Final Out PutJanel SalazarNo ratings yet

- Movie AnalysisDocument32 pagesMovie Analysissuhani vermaNo ratings yet

- CBT and Social Skills Training MaterialsDocument4 pagesCBT and Social Skills Training MaterialsNtasin AngelaNo ratings yet

- Publication (Kyei John) PDFDocument7 pagesPublication (Kyei John) PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence in Relation To PsDocument8 pagesEmotional Intelligence in Relation To PsAndy MagerNo ratings yet

- 626f PDFDocument20 pages626f PDFsacli.valentin mjNo ratings yet

- Attitude Measurement: Saul McleodDocument39 pagesAttitude Measurement: Saul McleodSukhwinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Effect Size in Psychological Research - Sense and NonsenseDocument25 pagesEvaluating Effect Size in Psychological Research - Sense and NonsenseJonathan JonesNo ratings yet

- The Self-Serving Attributional Bias: Beyond Self-PresentationDocument12 pagesThe Self-Serving Attributional Bias: Beyond Self-Presentation03217925346No ratings yet

- Thinking Dispositions ShariDocument5 pagesThinking Dispositions ShariGladys LimNo ratings yet

- Mind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingFrom EverandMind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Social Learning, Information Processing, and Evolutionary Theories of DevelopmentFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Social Learning, Information Processing, and Evolutionary Theories of DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Annex A List of Plantilla Vacancies For Rank and File Positions0817Document51 pagesAnnex A List of Plantilla Vacancies For Rank and File Positions0817Yani ZoiloNo ratings yet

- Part 3 of 4 Current Events and Problem SolvingDocument20 pagesPart 3 of 4 Current Events and Problem SolvingUmbina GesceryNo ratings yet

- The Immune System in Health and DiseaseDocument22 pagesThe Immune System in Health and DiseaseYani ZoiloNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of The Millenial Generation PDFDocument1 pageCharacteristics of The Millenial Generation PDFYani Zoilo100% (1)

- Exercise 2 Second Sem 1415Document2 pagesExercise 2 Second Sem 1415Yani ZoiloNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - in The Old HouseDocument8 pagesLesson Plan - in The Old HouseMicle Gheorghe-mihaiNo ratings yet

- Paper 8675Document6 pagesPaper 8675IJARSCT JournalNo ratings yet

- Empirical Methods For Evaluating Educational Interventions - ScienceDirectDocument2 pagesEmpirical Methods For Evaluating Educational Interventions - ScienceDirectMd HanafiahNo ratings yet

- AlaaDocument4 pagesAlaaAhmed SamirNo ratings yet

- Module-1 - Commn ErrorsDocument53 pagesModule-1 - Commn ErrorsSoundarya T j100% (1)

- Arenas - Universal Design For Learning-1Document41 pagesArenas - Universal Design For Learning-1Febie Gail Pungtod ArenasNo ratings yet

- ENG202 Ch11.PDF Delivering Your SpeechDocument28 pagesENG202 Ch11.PDF Delivering Your SpeechOmar SroujiNo ratings yet

- Benthem'S Theory of UtilitarianismDocument2 pagesBenthem'S Theory of UtilitarianismPrisyaRadhaNairNo ratings yet

- MUSIC THERAPY CompleteDocument18 pagesMUSIC THERAPY CompleteAnaMariaMolinaNo ratings yet

- 7 Mindful Eating Tips: 1. Shift Out of Autopilot EatingDocument1 page7 Mindful Eating Tips: 1. Shift Out of Autopilot EatingtedescofedericoNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan - Mockingbird Unit PDFDocument38 pagesUnit Plan - Mockingbird Unit PDFapi-245390199100% (1)

- Denes-Raj, V., & Epstein, S. (1994) .Document12 pagesDenes-Raj, V., & Epstein, S. (1994) .David Alejandro Alvarez MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Movement SkillsDocument20 pagesFundamental Movement SkillsEunice Kalaw Vargas100% (1)

- Communication ProcessDocument48 pagesCommunication ProcessPriya Sharma100% (1)

- Lesson 3 The Self From The Perspective of AnthropologyDocument17 pagesLesson 3 The Self From The Perspective of AnthropologyZhack Magus75% (4)

- Day6 7Document11 pagesDay6 7Abu Al-FarouqNo ratings yet

- BARICAUA MAYFLOR B. PBE Model EssayDocument1 pageBARICAUA MAYFLOR B. PBE Model EssayMayflor BaricauaNo ratings yet

- Lessonplan 1Document5 pagesLessonplan 1api-272727134No ratings yet

- Tactical Reality DictionaryDocument50 pagesTactical Reality Dictionaryslikmonkee100% (1)

- The Role of Society and Culture in The Person's DevelopmentDocument17 pagesThe Role of Society and Culture in The Person's DevelopmentJoseph Alvin PeñaNo ratings yet

- Low & High Context Culture (Adnan)Document5 pagesLow & High Context Culture (Adnan)PrinceakhtarNo ratings yet

- Improving Personal and Organizational Communication TopicDocument7 pagesImproving Personal and Organizational Communication TopicYvonne Grace HaynoNo ratings yet

- ESEG5223 - Group AssignmentDocument2 pagesESEG5223 - Group AssignmentSYED AMIRUL NAZMI BIN SYED ANUARNo ratings yet

- What Is LearningDocument6 pagesWhat Is LearningTerubok MasinNo ratings yet

- Paraphrase, Summary, and Precis - How To Write ThemDocument3 pagesParaphrase, Summary, and Precis - How To Write ThemAkshat MehtaNo ratings yet

- AI - ML Present ScenarioDocument28 pagesAI - ML Present ScenarioDr.Kishore Verma SNo ratings yet