Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sobre Cañas Saxofón PDF

Sobre Cañas Saxofón PDF

Uploaded by

PAULAROMAOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sobre Cañas Saxofón PDF

Sobre Cañas Saxofón PDF

Uploaded by

PAULAROMACopyright:

Available Formats

Paul Berler

Basic

Saxophone

Skills

Reeds, Part II

n my previous column (Reeds, Part

I) I discussed the preliminary

procedures in preparing reeds for

general use. Remember that these

techniques are quite helpful because they extend the life of the

reed, as well as making the reed

more useful for your individual

concept of sound and playing. I

hope also, in the time that has

passed between the last article and

this one, that you have procured

the necessary equipment to prepare,

adjust, and store your reeds:

flexible in order to alter its frequency

very quickly and efficiently, and start

and stop its vibration with the attack

and release of each tone. Now you can

see why it is so important to adjust

your reeds so they will be ready for

all this work!

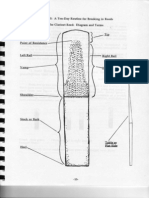

Now, lets review the important

parts of the reed. Again, please

refer to the diagram included.

1. Some sort of reed storage case,

preferably one in which the reeds

remain flat and dry

2. A plate of glass or Plexiglas, to use

as a surface for working on the reeds

(and make sure the sharp edges have

been smoothed).

3. Some sandpaper, 400 to 600 grit.

4. A reed knife, which can be purchased from most instrument shops.

Lets assume you have four reeds

that you have started to prepare.

Youve taken them through the first

and second phases of conditioning,

which simply involve soaking the

reeds and testing them for their individual strengths and weaknesses.

Remember that you should not be

using these reeds for general practicing and playing use yet! They are not

ready for the amount of exposure to

moisture and vibration we will put

them through. These reeds are now in

the testing and adjusting stages, which

will fine-tune them to become the kind

of reeds that you would love to have

straight out of the box: not too hard,

not too soft, and a consistently good

68

and uniform sound throughout all

registers and dynamic levels of your

saxophone.

Before we start to adjust our reeds,

its good to know the actual physical

makeup of a reed and why it works.

That way if there is a problem with a

particular reed, we know exactly

where to go to fix it. Please refer to the

diagram of a reed I have provided in

this article (F IGURE 1).

The main function of the reed is to

act as an air valve which opens and

closes the mouthpiece. The rate of

vibration or frequency of the reed

determines the pitch of the tone produced by the instrument. The reed

changes frequency with every new

pitch, thus, the reed must be very

1. THE TIP

This is the thinnest and most delicate region of the reed. It is responsible for the airtight seal created

against the tip of the mouthpiece, thus

its uniformity of size and thickness is

essential for good reed performance,

general response of the instrument,

and tone quality. This area should be a

last resort. Make all adjustments to

other parts of the reed before making

any adjustments to the tip. And even

then, those adjustments should be

minimal. Try to leave a little extra cane

in this area whenever possible, for if

the tip becomes too thin, the reed will

be rendered useless.

2. THE HEART

This area in the center of the reed is

responsible for the volume, projection,

and tone quality of the reed. Adjustments, like the tip, are almost never

made to the heart area. If necessary,

tiny adjustments can be made, but

only for a general effect.

3. THE CENTER OF RESISTANCE

This small area is responsible for the

uniform transmission of vibrations

from the thinner parts of the reed to

the heart. Adjustments made in this

area and around the heart region affect

March/April 1996

the tone and response of the reed in

the upper register. Be careful, however, because even the smallest of

adjustments made in this region can

cause major differences in the reeds

performance and quality.

4. THE SHOULDERS

If a reed is thicker or thinner on one

side than on the other, this is the region to adjust. The uniform thickness

of this area is essential to quality reed

performance and response. Also, if

you want to be really scientific, the

thickness of this area relative to other

areas will determine the reeds response in specific registers and at

specific dynamic levels.

5. THE UPPER VAMP

The upper vamp rails. The entire

section of the reed we are using to

make adjustments on is generally

known as the vamp. It is divided into

two sections, upper and lower, determined by the placement and size of

the heart region. The smooth area

(without the grain) which we do not

adjust is called the stock.

Removal of cane from one side or

the other of this area will affect the

reeds balance, response, and resonance. Be careful to make your adjustments to this area gradual and balanced. If you remove a certain amount

of cane from one side, do the same to

the other side.

6. THE LOWER VAMP

Some reeds have some extra wood

in this region. Removing this excess

cane can help to make hard reeds a

little more soft and flexible and usually

improves response in the lower register. Also, a general sanding of the

entire lower vamp region (the area

from the bottom of the heart to the

stock) will improve response in the

lower register.

7, 8, 9. UPPER, MIDDLE, AND

LOWER REGISTER ADJUSTMENT

AREAS

Adjustments made to these specific

regions of the reed, made after general

conditioning and balancing of the reed,

and made in conjunction with the

other regions of the reed, will help

with response and tone quality in

specific registers. The specific relationSaxophone Journal

ships are: Area 7 with areas 4 and 1;

area 8 with areas 4 and 5; area 9 with

areas 4 and 6.

So, after all of that, we are ready to

begin the third and fourth sessions of

our reed conditioning process. We

begin each session with a general

soaking for about ten minutes in the

glass of water as was described in the

previous column. After soaking, play

each reed for a few minutes to bring it

into what I call performance readiness, in preparation for the next step.

In the third session we want to polish

each reed. Polishing is used to assess

and correct any kind of warpage in the

reed, and also to compress and

smooth the reed fibers so that the reed

will not warp in future uses due to

rapid moisture exposure. Take a piece

of your sandpaper and place it, abrasive side down, on your piece of glass.

Take the reed and place it flat side

down on the back of the sandpaper.

While holding the sandpaper with one

hand, place your index finger on the

vamp, your thumb on the stock, and

gently move the reed in a back-andforth motion across the back of the

sandpaper. Make sure you exert an

equal amount of pressure on each side

of the reed, and make sure you do not

touch the tip of the reed with your

fingers, as you are liable to break or

warp it. You know the reed is polished

by rubbing the back of the reed and

having it be completely smooth. After

this, use the same procedure for the

vamp and side rails of the reed. Always make sure you are stroking in

the direction of the grain and not

against it. After the polishing procedure is finished, let each reed dry and

return it to storage.

Begin the fourth session with a

general soaking, and then play each

reed for a few minutes longer than in

the third session. After each reed is

played, check the reed for uniform

gloss, making sure there is no warping

from the polishing of the previous

session. Check the back side of the

reed for flatness. If the back seems at

all warped, uneven, or dull, you will

have to sand the reed in the following

manner: Put the sandpaper on your

glass plate, abrasive side up. Hold the

sandpaper in place with one hand, and

stroke the reed in a similar fashion to

that of polishing the reed. Stroke the

reed about ten times, then wipe away

the sanding residue, turn the sandpaper over, and polish the reed again.

Finally, coat the reed with saliva, place

on the mouthpiece, and test it. Repeat

this action, as necessary, for each reed.

After all the reeds have been properly

sanded to your liking, let them dry and

return them to storage.

After all of these sessions, increase

the amount of playing time for each

reed at every session, polishing and

sanding as necessary. Remember to

rotate the reeds on a regular basis so

that one reed does not become overused too quickly. These reeds, now

that they have gone through all the

general sessions, are ready for general

use and may be evaluated for other

future adjustments, if necessary.

69

You might also like

- A Guide To The Oboe and English HornDocument49 pagesA Guide To The Oboe and English HornCamillo Grasso100% (2)

- The Saxophone Is My VoiceDocument62 pagesThe Saxophone Is My VoiceJaviChúFernandez100% (1)

- Lotsawa House - Longchenpa - The PractitionerDocument3 pagesLotsawa House - Longchenpa - The Practitionerhou1212!No ratings yet

- Christmas duets for Alto & Tenor saxFrom EverandChristmas duets for Alto & Tenor saxRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Adjusting Saxophone and Clarinet ReedsDocument9 pagesAdjusting Saxophone and Clarinet ReedsEngin Recepoğulları50% (2)

- Building A Saxophone Techinique-Liley LearningDocument5 pagesBuilding A Saxophone Techinique-Liley Learningjimmywiggles100% (5)

- 05 Day One Handout - Saxophone FinalDocument6 pages05 Day One Handout - Saxophone Finalapi-551389172No ratings yet

- Clarinet EmbDocument4 pagesClarinet Embapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Overtones For SaxophoneDocument4 pagesOvertones For SaxophoneRafael CordovaNo ratings yet

- Joe Allard EmbouchureDocument23 pagesJoe Allard EmbouchureJacques Lejean100% (7)

- Larry Teal - The Art of Saxophone PlayingDocument6 pagesLarry Teal - The Art of Saxophone PlayingClaus HierlukschNo ratings yet

- Gotham Audio 1979 CatalogDocument16 pagesGotham Audio 1979 CatalogkeenastNo ratings yet

- Reeds How To Care For ThemDocument3 pagesReeds How To Care For Themdocsaxman100% (1)

- Care and Maintenance of ReedsDocument13 pagesCare and Maintenance of ReedsCamillo Grasso100% (1)

- 8 Saxophone CareDocument8 pages8 Saxophone Caretourloublanc33% (3)

- Tuning A Saxophone With CrescentsDocument7 pagesTuning A Saxophone With CrescentsGuilhermeNo ratings yet

- Price, Jeffrey - Saxophone Basics (US Army)Document18 pagesPrice, Jeffrey - Saxophone Basics (US Army)Саня ТрубилкоNo ratings yet

- Saxophone PlayingDocument9 pagesSaxophone PlayingDamian Yeo75% (4)

- Saxophone and Clarinet Fundamentals PDFDocument31 pagesSaxophone and Clarinet Fundamentals PDFAlberto Gomez100% (1)

- Art of Adjusting ReedsDocument44 pagesArt of Adjusting Reedsmadseven67% (3)

- Single Reed Reed Basics: Soak in WaterDocument4 pagesSingle Reed Reed Basics: Soak in Waterlorand88No ratings yet

- The Saxophone MouthpieceDocument2 pagesThe Saxophone MouthpieceSumit Sagaonkar100% (3)

- Williamson Saxophone Pedagogy TipsDocument1 pageWilliamson Saxophone Pedagogy TipsJeremy WilliamsonNo ratings yet

- Reed Adjusting PaperDocument41 pagesReed Adjusting PaperDiego Ronzio100% (2)

- Reed Adjustment PDFDocument6 pagesReed Adjustment PDFstefanaxe75% (4)

- A Guide To The Art of Adjusting Saxophone Reeds 2Document12 pagesA Guide To The Art of Adjusting Saxophone Reeds 2louish91758410% (1)

- Rico-Ultimate Tips For Saxophonists-Vol 2Document2 pagesRico-Ultimate Tips For Saxophonists-Vol 2chiameiNo ratings yet

- Meyer Bros Saxophone MouthpiecesDocument5 pagesMeyer Bros Saxophone MouthpiecesAndrea100% (1)

- Saxophone PedagogyDocument2 pagesSaxophone Pedagogyapi-217908378No ratings yet

- Saxophone NotebookDocument13 pagesSaxophone Notebookapi-269164217100% (2)

- Reed Adjustment ChartDocument2 pagesReed Adjustment ChartSumit SagaonkarNo ratings yet

- 2020 Eng PRG Sax PDFDocument68 pages2020 Eng PRG Sax PDFAndrea Sax Verlingieri100% (1)

- Saxophone Mouthpiece Buyers Guide Comparison Chart WWBW ComDocument4 pagesSaxophone Mouthpiece Buyers Guide Comparison Chart WWBW Comapi-199307272No ratings yet

- Tonguing ProperlyDocument5 pagesTonguing ProperlyAlejandro L Sanchez100% (1)

- Saxophone TechniqueDocument10 pagesSaxophone Technique_hypermusicNo ratings yet

- Sax Repair-3Document55 pagesSax Repair-3massoud_p3084100% (1)

- Adjusting Clarinet ReedsDocument15 pagesAdjusting Clarinet Reedsapi-201119152100% (1)

- Jeffs NAPBIRT Clinic 2012Document10 pagesJeffs NAPBIRT Clinic 2012Luiggi Fornicalli100% (2)

- Saxophone TechniquesDocument5 pagesSaxophone TechniqueshomeromeruedaNo ratings yet

- Rose - Early Evolution Sax MouthpieceDocument14 pagesRose - Early Evolution Sax MouthpieceOlia ChornaNo ratings yet

- Santy Runyon and The SaxophoneDocument8 pagesSanty Runyon and The SaxophoneJames BarreraNo ratings yet

- Setting Key Heights With The Balanced Venting MethodDocument13 pagesSetting Key Heights With The Balanced Venting MethodNina Kraguevska100% (1)

- Sax MouthpiecesDocument12 pagesSax Mouthpieceszillo8850% (2)

- Saxophone Basics: WWW - Wku.edu/ John - CipollaDocument1 pageSaxophone Basics: WWW - Wku.edu/ John - CipollaSamuele FazioNo ratings yet

- Tuning The SaxophoneDocument4 pagesTuning The SaxophoneJames BarreraNo ratings yet

- Methods Lecture NotesDocument13 pagesMethods Lecture NotesDesmond AndersonNo ratings yet

- Wolford Saxophone MasterclassDocument5 pagesWolford Saxophone MasterclassMusicalização Antonina100% (1)

- Optimal Saxophone ToneDocument17 pagesOptimal Saxophone Toneliebersax8282100% (3)

- Saxophone and Clarinet FundamentalsDocument32 pagesSaxophone and Clarinet FundamentalsFraz McMannNo ratings yet

- Dis Sax MultifonicDocument42 pagesDis Sax MultifonicDmitry Gemaddiev100% (1)

- Links Sax - Overhauls & Repair5 & PricesDocument18 pagesLinks Sax - Overhauls & Repair5 & PricesMarco GuimaraesNo ratings yet

- 10 Essential Reed Setup Tips BetterSaxDocument13 pages10 Essential Reed Setup Tips BetterSaxCielDreadNo ratings yet

- A Guide For Playing The SaxophoneDocument9 pagesA Guide For Playing The SaxophoneJan Eggermont100% (1)

- FIGURE 22. Parts of The SaxophoneDocument99 pagesFIGURE 22. Parts of The SaxophoneKamel Abou NorNo ratings yet

- 8 Things You Can Do Today To Instantly Pump Up Your Saxophone SoundDocument6 pages8 Things You Can Do Today To Instantly Pump Up Your Saxophone SoundAna PretnarNo ratings yet

- Saxo Alto ManualDocument5 pagesSaxo Alto ManualealoquetalNo ratings yet

- Saxophone Secrets: 60 Performance Strategies for the Advanced SaxophonistFrom EverandSaxophone Secrets: 60 Performance Strategies for the Advanced SaxophonistRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Basic Concepts and Strategies for the Developing SaxophonistFrom EverandBasic Concepts and Strategies for the Developing SaxophonistNo ratings yet

- The Science and Art of Saxophone Teaching: The Essential Saxophone ResourceFrom EverandThe Science and Art of Saxophone Teaching: The Essential Saxophone ResourceNo ratings yet

- Reed Adjustment Guide One PageDocument1 pageReed Adjustment Guide One PageCamillo GrassoNo ratings yet

- Reedual Operating ManualDocument7 pagesReedual Operating ManualCamillo GrassoNo ratings yet

- Reed Adjusting PaperDocument41 pagesReed Adjusting PaperDiego Ronzio100% (2)

- Oregon ScientificDocument123 pagesOregon ScientificCamillo GrassoNo ratings yet

- Care and Maintenance of ReedsDocument13 pagesCare and Maintenance of ReedsCamillo Grasso100% (1)

- Fiber Technology For Fiber-Reinforced Composites. © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All Rights ReservedDocument3 pagesFiber Technology For Fiber-Reinforced Composites. © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All Rights ReservedPao FrancavillaNo ratings yet

- Simple Easy Daily Mantras For All Above 40 MantrasDocument45 pagesSimple Easy Daily Mantras For All Above 40 MantrasDr Naresh ChawhanNo ratings yet

- Ethyl Chloride and Vinyl ChlorideDocument11 pagesEthyl Chloride and Vinyl Chlorideramchinna100% (2)

- Case Presented By: Group 1Document6 pagesCase Presented By: Group 1Manav LakhinaNo ratings yet

- Dog Food RecipesDocument284 pagesDog Food RecipesBusyNo ratings yet

- DOWSIL™ 795 Structural Glazing Sealant Technical Data SheetDocument5 pagesDOWSIL™ 795 Structural Glazing Sealant Technical Data SheetTrung Nguyễn NgọcNo ratings yet

- 12 - BIO - ZOO - 2nd - Revision - Lesson 5 - 8Document2 pages12 - BIO - ZOO - 2nd - Revision - Lesson 5 - 8Rangaraj RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Ketamine ZhaoPDocument12 pagesKetamine ZhaoPSutanMudaNo ratings yet

- Apqp Time Plan: Risk AnalysisDocument4 pagesApqp Time Plan: Risk AnalysisRakesh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Lab Cracking Paraffin PDFDocument2 pagesLab Cracking Paraffin PDFJeffreyCheleNo ratings yet

- Berkeley Math Circle: Monthly Contest 2 SolutionsDocument3 pagesBerkeley Math Circle: Monthly Contest 2 SolutionshungkgNo ratings yet

- Costing of PipelinesDocument29 pagesCosting of PipelinesShankar Jha100% (1)

- MODULE MCO 2 (PHYSICS Wednesday 25/3/2020 9.30 - 10.30) Analysing Impulse and Impulsive Force Impulse and Impulsive ForceDocument2 pagesMODULE MCO 2 (PHYSICS Wednesday 25/3/2020 9.30 - 10.30) Analysing Impulse and Impulsive Force Impulse and Impulsive ForceZalini AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Wisdom Philo TruthDocument10 pagesWisdom Philo Truthdan agpaoaNo ratings yet

- Condition-Based Maintenance of CNC Turning Machine: Research PaperDocument7 pagesCondition-Based Maintenance of CNC Turning Machine: Research Paperla pyaeNo ratings yet

- IIT Kharagpur LecturesDocument616 pagesIIT Kharagpur LecturesBhavanarayana Chakka67% (3)

- Ethiopia Country Case Study Mining Sector Feb 2018Document7 pagesEthiopia Country Case Study Mining Sector Feb 2018Fekadu AlemayhuNo ratings yet

- Las 2.3 in Hope 4Document4 pagesLas 2.3 in Hope 4Benz Michael FameronNo ratings yet

- FPA Bulletin June21Document40 pagesFPA Bulletin June21prabu mahaNo ratings yet

- Ehnv1 Est1: EQP-, EP-and Two-Phase Titration Function FunctionsDocument2 pagesEhnv1 Est1: EQP-, EP-and Two-Phase Titration Function FunctionsFernando Chacmana LinaresNo ratings yet

- EPA Method 7420Document4 pagesEPA Method 7420Wilder Mancilla GómezNo ratings yet

- Thong So Banh RangDocument7 pagesThong So Banh RangVũ Trường LamNo ratings yet

- Sonic Velocity Mach Number PDFDocument2 pagesSonic Velocity Mach Number PDFShreyasGadkariNo ratings yet

- INBAR-2023-Combating Climate Change With BambooDocument24 pagesINBAR-2023-Combating Climate Change With BambooKay-Uwe SchoberNo ratings yet

- Bahan Ajar AminaDocument44 pagesBahan Ajar AminaAnindya Putri KurniasariNo ratings yet

- Spectacles: Spectacle MaterialDocument8 pagesSpectacles: Spectacle MaterialALi SaeedNo ratings yet

- Geography - Industries-The Pitch LakeDocument6 pagesGeography - Industries-The Pitch LakeShannen NaraceNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 2 - Module 9 Different Contemporary Art Techniques and PerformanceDocument25 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 2 - Module 9 Different Contemporary Art Techniques and PerformanceGrace06 Labin100% (7)