Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clinical Case Report

Clinical Case Report

Uploaded by

cameliamorariuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Case Report

Clinical Case Report

Uploaded by

cameliamorariuCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology

ISSN 1697-2600

2008, Vol. 8, N 3, pp. 765-777

RAMOS-LVAREZ et al. Guidelines of the peer-review process for publication

765

Guidelines for clinical case reports in behavioral

clinical Psychology1

Javier Virus-Ortega2 (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Espaa) and

Rafael Moreno-Rodrguez (Universidad de Sevilla, Espaa)

( Recibido

30 de octubre 2007/ Received October 30, 2007)

(Aceptado 11 de marzo 2008 / Accepted March 11, 2008)

ABSTRACT. This theoretical study describes guidelines for writing clinical case reports

in cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavior therapy and applied behavior analysis. Emphasis

is laid upon the constraints to be applied in order to enhance the validity of clinical

case reports. Lack of validity is a common shortcoming in clinical case reporting which

limits research results interpretation and usability. A number of suggestions are made

throughout the manuscript in order to strengthen single-subject designs validity. The

manuscript makes the case for the contribution of clinical case reports to clinical

research and empirically-based clinical practices. Guidelines for drawing up clinical case

report are given. The following manuscript sections are suggested: abstract, introduction,

patient identification and reason for referral, assessment strategies, clinical case formulation,

treatments, study design, data analysis, effectiveness and efficiency of the intervention,

and discussion. The paper provides a general and flexible framework for each of these

areas. Consistency with the constraints of common clinical practices and settings is

intended.

KEY WORDS. Guidelines. Single-case experiment. Case studies. Case series. Clinical

case formulation. Theoretical study.

1 Authors would like to thank Dr. Stephen N. Haynes (University of Hawaii) for his numerous and

constructive comments to previous drafts of this manuscript. This research was supported by the

Network of Co-operative Epidemiological and Public Health Research Centers (Centros RCESP)

and the Neurological Disease Research Network (Red CIEN) (Spain).

2 Correspondence: Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Centro Nacional de Epidemiologa. C/ Sinesio

Delgado, 6. 28029 Madrid (Espaa). E-mail: jvirues@isciii.es

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

766

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

RESUMEN. El presente estudio terico es una gua para la redaccin de informes de

casos clnicos en terapia cognitivo-conductual, modificacin de conducta y anlisis

aplicado del comportamiento. La falta de validez es una limitacin frecuente en los

informes de casos clnicos; ello limita la interpretacin y uso de los resultados de

investigacin. El artculo ofrece guas especficas a objeto de mejorar la validez de

informes de casos clnicos y los diseos de caso nico. El manuscrito llama la atencin

sobre la contribucin de los informes de casos en la investigacin clnica y en el

desarrollo de prcticas clnicas apoyadas en evidencias. Se ofrecen guas para la preparacin de casos clnicos siguiendo la siguiente estructura de secciones: resumen,

introduccin, identificacin del paciente y motivo de referencia, estrategias de evaluacin, formulacin clnica del caso, tratamientos, diseo del estudio, anlisis de datos,

efectividad y eficiencia de la intervencin y discusin. El artculo ofrece un margo

general y flexible para cada una de estas reas intentando ser consistente con las

posibilidades y limitaciones propias de la prctica clnica.

PALABRAS CLAVE. Gua. Experimento de caso nico. Estudios de casos. Series de

casos. Formulacin clnica de casos. Estudio terico.

Clinical case reports (CCRs) also known as case studies and clinical cases are

descriptions of the assessment and/or treatment of a client or group of clients. CCRs

enable particular cases to be described in great detail, so that they may be more

instructive to clinicians than studies on the averaged performance of groups. CCR

interest is frequently related to reporting new findings that lack replication with groupbased methodology. They frequently address new methods, new applications of old

methods, low frequency behaviors or unexpected findings. In addition, CCRs may

provide preliminary information on the effects of a known assessment or treatment

strategy on a new population or the effects of a new form of treatment or implementation

of a new assessment procedure. Finally CCR may also inform about outstanding or

unpredicted effect of a known form of assessment or treatment.

Current status of CCR in psychological literature

In spite of the relevant contributions of the CCRs a number of clinicians may

regard their own clinical practice as lacking scientific interest. Clinicians may consider

their practice incompatible with scientific standards (Borckardt and Nash, 2002). Indeed,

the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology and Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

two of the most prestigious clinical psychology journals which accept methodologicallysound case reports, have not published any for years. However, under certain

methodological constraints, CCRs enable preliminary tests to be conducted on the

utility and effectiveness of novel treatments and clinical methods. In such circumstances,

the CCR is a cost-effective option prior to implementing more complex research methods.

For instance, Jones, Ghannam, Nigg, and Dyer (1993) have shown that for clinical cases

the long-term time-series design is a methodologically sound choice for studying causal

therapist-client interactive processes in psychotherapy and psychopathology. Additionally,

the application of clinical case formulation strategies to CCRs has revealed high convergent

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

validity for the identification of behavioral and cognitive clinical scenarios among

therapists (Mumma and Smith, 2001). In summary, CCR provide a methodological tool

for testing aspects of the therapeutic process that can hardly be addressed through

group based methods.

CCRs have been frequently used in clinical research (see Special Issue in Singlecase methodology in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1993, Vol. 61),

and have regularly been published in behavior analysis, cognitive therapy, cognitivebehavioral therapy and other fields of psychology for over 50 years. A single search

of documents with clinical case study methodology in PsycINFO (1997-2007) yielded

16,909 peer-reviewed entries (Search strategy: Clinical case study in Methodology

and 1997-2007 in Publication Year). In addition, there are a number of journals,

including Behavior Therapy, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, Clinical Case Studies,

among others, committed to the publication of CCRs.

The goal of this theoretical study is to present guidelines that may be useful for

clinicians in conducting and presenting CCRs as journal articles. It is hoped that the

guidance herein suggested may upgrade the validity of case studies. The present

manuscript is an update of Buela-Casal and Sierras (2002) previous effort to clarify the

task of publishing CCRs at the International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology.

The variety of orientations and sub-fields in clinical psychology precludes the wide

usage of restrictive guidelines for CCRs. Let us consider how different a case study on

clinical neuropsychology, cognitive therapy and applied behavior analysis could be.

The guidelines suggested here are primarily adapted to behavioral and cognitive-behavioral

assessment and treatment.

Writing CCRs: Sections

Title

Title should not be longer than 15-20 words. It should clearly portray the behavior

problem and type of intervention. The main result could also be mentioned if particularly

relevant or new.

Abstract and key words

The Abstract is a key section of any CCR. It should allow the reader become familiar

with the main features of the case. The Abstract should describe the number, age and

gender of patients, goal of the intervention, type of treatment, assessment and instruments

used, design, data-analysis (if any), outcomes, and duration of follow-up. Indeed,

despite its location at the commencement of the paper, common sense dictates that it

should be written only after the manuscript has been drafted. The Abstract should be

no more than 200-250 words in length. In order to facilitate database searching the term

single-case experiment should be among the keywords (Montero and Len, 2007).

Introduction

In this section, the authors should outline the general goal(s) of the CCR with a

detailed explanation of the rationale for such goal(s). All CCRs should be provided in

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

768

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

the context of relevant empirical literature. It is even an ethical standard that clinicians

be familiar with the literature associated with the behavior problem and treatment they

are using (American Psychological Association, 2002). Authors must explicitly describe

the gap in knowledge that the paper seeks to address and explain the particular interest

that resides in the CCR. The Introduction section might be more expansive in cases

where the preliminary effects of a novel procedure are reported.

Patient identification and reason for referral

CCRs can involve a single case or multiple cases. In case series, participants may

share a major factor (e.g., type of intervention, behavior problem). In such studies each

subject should be described separately while the abstract and introduction may be

shared. In addition, information about the patients identification could be presented in

tabular form. Authors must include age, gender, and other personal features relevant to

the internal and external validity of the assessment and treatment modality. Forms of

personal information that may be relevant include subjects academic background,

profession, culture and family status and past and current diagnoses.

Information on past and current treatment efforts should also be provided. Where

there is concurrent psychological treatment, the author should give details on the type,

duration, session-frequency, results and/or focus of such intervention (e.g., systemic

therapy; bi-weekly; preceding five months; inter-generational boundaries). If there is a

concurrent pharmacological intervention, the author should report the active principle

and dosage of any medication being used in addition to the prorenata medication, if

applicable (e.g., haloperidol, 15 mg once per day). It is difficult to obtain reliable

information on the past pharmacological treatments of many patients; hence, authors

should only report on the current medication.

For institutionalized patients, the unit to which the patient is assigned should be

roughly described (e.g., day hospital, open rehabilitation unit, psychiatric hospital with

dynamic group sessions and occupational therapy).

Furthermore, the reason for referral and its source (i.e., patient, family, mental health

unit, other clinician) must be briefly clarified. In cases where there are discordances

between client and clinician criteria as to the focus of assessment and treatment, the

authors are to say so, supplying details of any eventual agreement reached as regards

treatment. All aspects concerning confidentiality and patients informed consent should

be outlined in this section.

Assessment strategies

Multimethod and multisource assessment are highly recommended as the basis for

addressing the component variables of clinical case formulation (e.g., interview with

multiple informants, assessment in different occasions, naturalistic observation, selfrecording, self-reports) (see definitions at Haynes, 2005). When behavior parameters are

measured (e.g., frequency, duration, latency) there should be a supporting framework

for the parameters selection and inter-rater reliability estimates should be warranted (see

Cooper, Heron, and Heward, 2006). In the latter cases some broad measure of functioning

is advised (e.g., CI, social functioning, quality of life, family burden) for the purposes

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

of informing the wider impact of the intervention. Also, the implementation of frequent

assessment or time-series assessment is highly encouraged. When possible, in addition

to clinically relevant domains, the assessment of potential side effects should be warranted.

Behavioral CCRs have used standardized scales as measures of pre-post effectiveness

and as an indirect index of results generalization (e.g., Sloan and Mizes, 1996; VirusOrtega, 2004). In addition, they can be used as a method of independent verification

(Sidman, 1960), by comparing the impact of an intervention in a case report with that

in a clinical trial or other group design, which implemented the same standardized

measures (e.g., Moras, Telfer, and Barlow, 1993). When self-report questionnaires are

used, authors should: a) highlight validation studies on the population targeted by the

instrument; b) provide an explanation on the relationship of the construct assessed by

the test with assessment and intervention foci and add references on the predictive

validity of the instrument; and, d) in cases where the instruments are used at different

time points during the treatment process, specify if parallel forms were used or if a

possible practice effect could be overlooked according to the available literature. Further

details on assessment methods in Haynes and Heiby (2004), and Moreno and Martnez

(2005).

Clinical case formulation

A summarization of the information relevant to describe and explain a given patients

behavior problem is called a clinical case formulation. Clinical case formulations allow

for a molecular approach to patients behavior problems, which can include behaviorproblem components, historical factors, biological processes and environmental factors

associated with the behavior problem, when the particular features of the case so

require. A clinical case formulation is the main outcome of the assessment process and

should constitute a concise description specifying the dysfunctional behavior or classes

of behavior to be targeted by the intervention. Clinical case formulations can be developed

from a functional or a non-functional (i.e., topographically-driven) perspective (see a

commentary on the topography/function dichotomy in Hayes, Strosahl, Luoma, Varra,

and Wilson, 2005). There are several models of clinical case formulations; authors are

referred to specific outlines by Haynes and OBrien (2000) and Nezu, Nezu, Peacock, and

Girdwood (2004).

CCRs should furnish details on the description of the behavior problem itself. Aside

from providing some detail on when, how and under what circumstances the behavioral

problems were acquired in case the information is available. However, as far as treatment

design current maintaining variables are of greater interest, which could be different

from the determinants at first acquisition (Virus-Ortega and Haynes, 2005).

Treatments

In this section, CCR authors are to furnish details on the type of treatment judged

to be most appropriate for the case being described and the rationale for the choice of

treatment. Treatment-related circumstances including therapist-related factors should be

also specified here.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

770

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

Choice of treatment

An important issue is to tie in treatment to the prior assessment. The literature

highlights a number of methods for treatment selection, including:

Selection of the most effective treatment for a particular disorder. This procedure

enables the most effective, manualized, topographically-driven treatment to be

chosen for a given disorder in line with available literature on empiricallysupported treatments (Chambless and Hollon, 1998; Edwards, Dattilio, and Bromley,

2004). Treatment integrity or fidelity refers to degree to which a treatment has

been implemented as intended. Providing information on treatment integrity is

particularly advised when this pathway for treatment selection is chosen (see

Perepletchikova and Kazdin, 2005).

Functional analysis of behavior: functional analysis allows for the identification

of current causal variables affecting a clients behavior problem. In doing so,

functional analysis methodology makes it possible to design programs to address

and modify those causes. Functional analysis is actually a form of clinical case

formulation providing indications for treatment selection and design. There are

a number of functional analysis models in the literature (see reviews by Iwata,

Kahn, Wallace, and Lindberg, 2000, Sturmey, 2007; and Virus-Ortega and Haynes,

2005).

Trans-theoretical models of treatment selection: a few authors have suggested

logical models for treatment selection, largely on the basis of an underlying

psychotherapeutics integration model, or according to patients individual features

(e.g., Lazarus, 1989; Prochaska and Norcross, 1994).

Other procedures: as mentioned above, novel methods, treatments or populations

(e.g., Moras et al., 1993). Thus, restricting the pathways for treatment selection

could result in the heuristic value of clinical case methodology being undermined.

If the author reporting the clinical case does not use any of the above-mentioned

treatment selection procedures, the reasons for doing so ought to be specified.

More importantly, authors should provide a strong rationale, citing relevant

research on why they have chosen a particular treatment.

Treatment implementation

Authors could also describe the number, periodicity, duration and content of the

clinical sessions (e.g., Labrador, Fernndez-Velasco, and Rincn, 2006). To ensure that

therapeutic techniques or certain particulars of the clinical sessions are clearly explained,

short transcripts of clinical dialogues or session-by-session descriptions could be

added in this section (e.g., Espada, van der Hofstadt, and Galvn, 2007). Details on the

techniques used and the sequence of their implementation should also be included in

this section (Buela-Casal and Sierra, 2001; Labrador, Echebura, and Becoa, 2000;

Olivares and Mndez, 2001). Furthermore, readers would find it useful if a chronogram

could be included, displaying the clinical goals addressed, techniques used and session

content (Echebura and Corral, 2001). The information in this section may suffice for

readers to check treatment fidelity if any treatment procedure was implemented as

suggested by original authors.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

Therapist-related factors

A subject frequently neglected in CCRs is the therapeutic relationship. However,

there is abundant literature to suggest that therapist-related factors have an enormous

impact at times even greater than the therapists theoretical or academic backgroundon the outcome of the intervention (Kohlenberg et al., 2005; Norcross, 2002). Authors

shall mention the procedures used to enhance treatment adherence and therapeutic

alliance (e.g., self-disclosure, feedback etc., see a review in Norcross, 2002). Moreover,

report quality benefits from the participation of multiple therapists (in case series) and

from information furnished on therapists background and training (e.g., specialized

board certification holder), so that the reader could form a rough idea of the likely impact

of therapist-related factors. In summary, it is advised that therapist prompt adherence

and therapeutic alliance through explicit procedures. Measures of adherence could

involve count of missing appointments, relative count of homework compliance and the

like (see a review by Maci and Mndez, 1996).

Additionally, clinical decision-making bias is particularly relevant to CCRs. For

instance, therapists might perceive improvements when there had been none, attach

excessive importance to information obtained at the beginning of the assessment process,

or indiscriminately deem items of information reliable or unreliable (see a monographs

on clinical decision-making by Godoy, 1996). In clinical case studies there is no opportunity

for such errors to by randomly distributed, as is the case for group studies with several

therapists. The impact of clinical decision-making bias could be minimized by using

objective dependent measures, empirically supported assessment instruments and clinical

case formulation strategies designed to address biases in clinical judgment (e.g., Haynes

and Williams, 2003).

Study design

The simplest choice are AB designs, which may often be the only option for

clinicians who do therapy with adults in public and private settings, as designs

implementing a second A phase may give rise to ethical and cost-efficiency concerns.

AB designs do not imply a return to baseline in order to ensure causal dependency

between the intervention and the outcome variable. However, whenever possible, CCR

designs should allow for comparison of data on dependent variables from different

consecutive conditions or treatment levels. In doing so, clinicians would be able

to observe the covariation between conditions and behavioral dependent variables.

Subject-, context- and therapist-related confounding variables need to be controlled for

in order to support the causal nature (i.e., internal validity) of the potential relationships.

Additionally, a dependent-variable data series should be available for each condition

to ensure adequate reliability and representativeness of the conclusions. Comparisons

will be clearer where data series are stable and evince low variability.

Comparisons can be made according to a range of criteria, i.e., number and type

of treatment conditions, reversal to previous conditions, number of treatments, and

number of dependent variables. Accordingly, these criteria in turn generate a number of

single-case designs, including AB, ABAB, ABCB, BCB, and multiple baseline designs,

among others. The reader is referred to Franklin, Allison and Gorman (1996), Hineline

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

772

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

and Lattal (2000), and Kazdin (2003) for a detailed account on single-case experiments

designs.

Data analysis

Visual analysis of session-by-session data is the simplest alternative to drawing

conclusions from the comparison phases in a CCR (Arnau, 1995; Parsonson and Baer,

1992; Poling, Methot, and LeSage, 1995). Visual analysis may be feasible when changes

in level and trend are: a) extensive; b) the series compared display low variability; and,

c) the baseline trend is stable or demonstrates a trend that runs counter to the expected

direction of the treatment effect. Moreover, the scale range and type of graphs used,

whether too small or too wide, should not over-report or minimize any difference in the

data (Bailey, 1984).

Non-adherence to the above-mentioned requirements is frequent in CCR literature

(Borckardt, Murphy, Nash, and Shaw, 2004; Nugent, 2000). Indeed, Parker et al. (2005)

reported -over 77 CCRs analyzed- that 66% baselines had positive or negative trends,

and 50% of the studies had baselines with high variability. Therefore it is suggested

to take advantage of the benefits of statistical analysis to complete impressions obtained

through visual analysis with quantitative information. Statistical analysis may be assured

when baseline is unstable and there is a need to share the results with other professionals

(Kazdin, 2003).

If statistical analyses of single-case data are to be implemented the issue of selfcorrelation should be properly addressed. Auto-correlation is a trend toward covariation

shown by data obtained from the same individual at different time intervals. Autocorrelation may confound the potential treatment effects, and thereby threaten the

internal validity of conclusions. A number of strategies have been proposed for avoiding

self-correlation, including parametric and non-parametric analyses. Potential contributors

are referred to Arnau (1995) for details on the implementation of these analyses.

Effectiveness and efficiency of the intervention

Main results should be described in this section. Whenever possible authors shall

report: a) differences in level or trend versus baseline in the dependent variables,

whether detected by statistical or visual analysis; and, b) effect size if available, c) a

description of the clinical significance of the results. Sometimes, small effects, whether

visually or statistically detected, may be relevant or adaptive to the individual or his

environment. If properly chosen, dependent measures will automatically furnish information

on clinical significance. When this outcome is not warranted ecological measures on the

effect of the intervention on individuals daily environment should be added (e.g., thirdpart informants report, analogue observations, standardized pre- post-measurements).

Even when no statistical analysis is conducted, authors are advised to provide mean

and standard deviations of pre- and post-test and correlation (if applies) of pre- and

post-test outcome variables so the study could be included in effect size meta-analysis

(Botella and Gambara, 2006; Morris and DeShon, 2002).

In this section, it is essential to explain how the results are expected to be maintained

and become generalized in terms of individuals daily lives, once the treatment is

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

discontinued. Authors should mention the mechanism in terms of which such generalization

is expected to occur (e.g., Fowler and Baer, 1981).

This section may also describe the specifics of treatment follow-up. Follow-up

makes it possible to ascertain whether the treatment and the maintenance and

generalization strategies were successful in the long-term. Authors can specify if a

follow up phase was conducted and over what period of time.

While follow-up periods should be no shorter than three months, periods of one

year or longer are strongly suggested, particularly for studies on behavior problem with

a long history or with a known risk of relapse (e.g., drug addictions). It should be noted

that the ability to provide longitudinal data is one of CCRs advantages.

Discussion

The final section of the report could include a concise evaluation of the results in

the context of the clinical formulation and the intervention designed. In cases where

results fail to fulfill expectations, informed preliminary hypotheses could provide the

reader with some insight into what actually happened. In addition, outcomes could be

discussed in the context of the available literature on the topographies intervened or

the treatment mechanisms implemented. The Discussion section may provide detail on

aspects that the report helps elucidate and any other aspect that remains unclear as well

as any shortcomings of the study.

Summary

The opinion, held by many clinicians, suggesting that CCRs have a limited scientific

value, coupled with the lack of clear guidance as to how to draw up and write them,

have contributed to the current neglect of single-case methodology in most published

CCRs. Nevertheless, there is widespread evidence to show that CCRs make a relevant

scientific contribution, with great impact on the development, expansion and assessment

of the effectiveness of new forms of intervention.

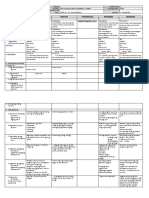

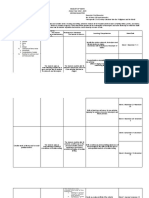

Table 1 summarizes the contents spelled out in these guidelines and it may be used

as a user-friendly outline for authors and referees of International Journal of Clinical and

Health Psychology and other journals. By adhering to these points, CCRs could be

made clearly useful as well as scientifically valid for assessing the effectiveness of

psychological treatments and ascertaining the mechanisms whereby psychological

treatments operate.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

774

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

TABLE 1. Summary of sections and major contents for clinical case reporting.

Section

Title (max. 20 words)

Abstract (max. 250 words)

Key-words

Introduction

Patient identification and

reason for referral

Assessment strategies

Clinical case formulation

Treatments

Choice of treatment

Treatment

implementation

Therapist-related

factors

Study design

Data analysis

Effectiveness and

efficiency of the

intervention

Discussion

Contents

Highly descriptive

Personal data*

Goal of the study/intervention*

Assessment methods*

Type of treatment

Design

Data-analysis

Major results*

Follow-up

Add single-case experiment*

Goals and rationale*

Relevant empirical background*

Descriptive information: age, gender, education, profession, family status*

Clinical background: past and current diagnoses and treatments

Reason for referral*

Informed consent and confidentiality*

Past treatments (psychological and pharmacological)

Behavior parameters and rationale

Inter-rater reliability

Empirical literature and rationale on instruments Use of general

functioning measures

Assessment of side-effects

Problem description*

Circumstances of problem acquisition

Maintaining variables

Summarization of the information relevant to describe and explain a given

patients problem*

Hypotheses*

Method for treatment selection

Number, periodicity, duration and content of the clinical sessions

Chronogram

Session-by-session description

Short sessions transcript

Treatment fidelity measures

Methods enhance treatment adherence

Single/Multiple therapists

Information on therapist background

Measures of adherence

Methods to minimize clinical decision-making bias

Time-series measurements

Design diagram (AB, ABA, ABAB, etc.)

Subject-, context- and therapist-related confounding variables control

Rationale for visual or statistical analysis*

Departures from baseline

Intervention effect size

Clinical significance of the intervention

Pre- and post-test data

Follow-up period

Evaluation of the results in the context of the clinical formulation, the

intervention designed and the relevant empirical literature*

Study highlights*

Study shortcomings*

Topics for future research*

(*) Required information.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

References

American Psychological Association (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of

conduct. Retrieved July 20, 2007, from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code2002.html

Arnau, J. (1995). Anlisis estadstico de datos para los diseos de sujeto nico. In M.T. Anguera,

J. Arnau, M. Ato, R. Martnez, J. Pascual, and G. Vallejo (Eds.), Mtodos de investigacin

en psicologa (pp. 151-174). Madrid: Sntesis.

Bailey, D.B. (1984). Effects of lines of progress and semilogarithmic charts on ratings of charted

data. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 17. 359-365.

Borckardt, J.J., Murphy, M.D., Nash, M.R., and Shaw, D. (2004). An empirical examination of

visual analysis procedures for clinical practice evaluation. Journal of Social Service

Research, 20, 55-73.

Borckardt, J.J. and Nash, M.R. (2002). How practitioners (and others) can make scientifically

viable contributions to clinical-outcome research using the single-case time-series design.

International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 50, 114-148.

Botella, J. and Gambara, H. (2006). Doing and reporting a meta-analysis. International Journal

of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6, 425-440.

Buela-Casal, G. and Sierra, J.C. (2001). Manual de evaluacin y tratamientos psicolgicos.

Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

Buela-Casal, G. and Sierra, J.C. (2002). Writing norms for clinical cases. International Journal

of Clinical and Health Psychology, 2, 525-532.

Chambless, D.L. and Hollon, S.D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 7-18.

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E., and Heward, W.L. (2006). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). New

York: Prentice-Hall.

Echebura, E. and Corral, P. (2001). Eficacia de las terapias psicolgicas: de la investigacin a

la prctica clnica. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 1, 181-204.

Edwards, D.J., Dattilio, F.M., and Bromley, D. (2004). Developing evidence-based Practice: The

role of case-based research. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35, 589-597.

Espada, J.P., van der Hofstadt, C., and Galvn, B. (2007). In vivo exposure and cognitivebehavioral techniques in a case of panic attacks with agoraphobia. International Journal

of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7, 217-232.

Fowler, S.A. and Baer, D.M. (1981). Do I have to be good all day? The timing of delayed

reinforcement as a factor in generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 14, 1324.

Franklin, R.D., Allison, D.B., and Gorman, B. S. (1996). Design and analysis of single-case

research. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Godoy, A. (1996). Toma de decisiones y jucio clnico. Madrid: Pirmide.

Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., Luoma, J., Varra, A.A., and Wilson, K.G. (2005). ACT case

formulation. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, Inc.

Haynes, S.N. (2005). Glossary of psychometric and measurement terms. Retrieved October 27,

2007, from http://www2.hawaii.edu/~sneil/ba/

Haynes, S. N. and Heiby, E.H. (Vol. eds.). (2004). In M. Hersen (Series Ed.), Comprehensive

handbook of psychological assessment: Vol. 3. Behavioral assessment. Hoboken, NJ:

Wiley.

Haynes, S.N. and OBrien, W.H. (2000). Principles and practice of behavioral assessment. New

York: Kluwer.

Haynes, S.N. and Williams, A.E. (2003). Case formulation and design of behavioral treatment

programs. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19, 164-174.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

776

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

Hineline, P.N. and Lattal, K.A. (2000). Single-case experimental design. Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

Iwata, B.A., Kahn, S.W., Wallace, M.D., and Lindberg, J.S. (2000). The functional analysis model

of behavioral assessment. In J. Austin and J.E. Carr (Eds.), Handbook of Applied

Behavior Analysis (pp. 61-89). Reno, NE: Context Press.

Jones, E.E., Ghannam, J., Nigg, J.T., and Dyer, J.F. (1993). A paradigm for single-case research:

The time series study of a long-term psychotherapy of depression. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 61, 381-394.

Kazdin, A.E. (2003). Research designs in clinical psychology (4th ed.). Boston: MA: Allyn and

Bacon.

Kohlenberg, R.J., Tsai, M., Ferro, R., Valero, L., Fernndez, A., and Virus-Ortega, J. (2005).

Psicoterapia analtico-funcional y terapia de aceptacin y compromiso: Teora, aplicaciones y continuidad con el anlisis del comportamiento. International Journal of Clinical

and Health Psychology, 5, 349-371.

Labrador, F., Echebura, E., and Becoa, E. (2000). Gua para la eleccin de tratamientos

psicolgicos efectivos: Hacia una nueva psicologa clnica. Madrid: Dykinson.

Labrador, F., Fernndez-Velasco, M.R., and Rincn, P.P. (2006). Eficacia de un programa de

intervencin individual y breve para el trastorno por estrs postraumtico en mujeres

vctimas de violencia domstica. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology,

6, 527-547.

Lazarus, A.A. (1989). The practice of multimodal therapy. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins

University Press.

Maci, D. and Mndez, X. (1996). Evaluacin de la adherencia al tratamiento. In G. Buela-Casal,

V.E. Caballo, and J.C. Sierra (Eds.), Manual de evaluacin en psicologa clnica y de la

salud (pp. 43-60). Madrid: Siglo XXI.

Montero, I. and Len, O.G. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International

Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7, 847-862.

Moras, K., Telfer, L.A., and Barlow, D.H. (1993). Efficacy and specific effects data on new

treatments: A case study strategy with mixed anxiety-depression. Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, 61, 412-420.

Moreno, R., and Martnez, R. (2005). Teoras conductuales y Tests psicolgicos [Special Issue].

Acta Comportamentalia, 13 .

Morris, S.B. and DeShon, R.P. (2002). Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with

repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7, 105-125.

Mumma, G.H. and Smith, J.L. (2001). Cognitive-behavioral interpersonal scenarios: Inter-formulator

reliability and convergent validity. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,

23, 203-221.

Nezu, A.M., Nezu, C.M., Peacock, M.A., and.Girdwood, C.P. (2004). Case formulation in

cognitive-behavior therapy. In S.N. Haynes and E.H. Heiby (Vol. eds.) and M. Hersen

(Series Ed.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment: Vol. 3 (pp. 402-426).

Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Norcross, J.C. (2002). Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and

responsiveness to patient needs. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nugent, W.R. (2000). Single case design visual analysis procedures for use in practice evaluation.

Journal of Social Service Research, 27, 39-75.

Olivares, J. and Mndez, F.X. (2001). Tcnicas de modificacin de conducta. Madrid: Biblioteca

Nueva.

Parker, R.I., Brossart, D.F., Vannest, K.K., Long, J.R., Garca-De-Alba, R., Baugh, F.G., and

Sullivan, J.R. (2005). Effect sizes in single case research: How large is large? School

Psychology Review, 34, 116-132.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

VIRUS-ORTEGA and MORENO-RODRGUEZ. Clinical case report guidelines

Parsonson, B. S. and Baer, D.M. (1992). The visual analysis of data, and current research into

the stimuli controlling it. In T.R. Kratochwill and J.R. Levin (Eds.), Single case research

design and analysis (pp. 15-40). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Perepletchikova, F. and Kazdin, A.E. (2005). Treatment integrity and therapeutic change: Issues

and research recommendations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12, 365-383.

Poling, A., Methot, L.L. and LeSage, M.G. (1995). Basic research design in applied behavior

analysis. In A. Polong and W. Fuqua (Eds.), Research methods in applied behavior

analysis: Issues and advances. New York: Plenum Press.

Prochaska, J.O., and Norcross, J.C. (1994). Systems of psychotherapy: A transtheoretical analysis

(3rd Ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Sidman, M. (1960). Tactics of scientific research. New York: Basic Books.

Sloan, D.M. and Mizes, J.S. (1996). The use of contingency management in the treatment of

a geriatric nursing home patient with psychogenic vomiting. Journal of Behavior Therapy

and Experimental Psychiatry, 27, 57-65.

Sturmey, P. (2007). Functional analysis in clinical treatment. New York: Elsevier.

Virus-Ortega, J., (2004). Functional analysis and treatment of a patient with severe behavioral

disturbances diagnosed with BPD. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology,

4, 207-232.

Virus-Ortega, J. and Haynes, S.N. (2005). Functional analysis in behavior therapy: Behavioral

foundations and clinical application. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology,

5, 567-587.

Int J Clin Health Psychol, Vol. 8. N 3

You might also like

- Piliavin's Study On Good Samaritanism (1969)Document5 pagesPiliavin's Study On Good Samaritanism (1969)cora4eva5699100% (1)

- RISB TestDocument7 pagesRISB TestIrsa Zaheer100% (2)

- Young Mania Rating Scale (Ymrs) : Guide For Scoring ItemsDocument7 pagesYoung Mania Rating Scale (Ymrs) : Guide For Scoring ItemsAsepDarussalamNo ratings yet

- Beck Cognitive Insight ScaleDocument3 pagesBeck Cognitive Insight ScalesrinivasanaNo ratings yet

- Expressed Emotion: Camberwell Family InterviewDocument3 pagesExpressed Emotion: Camberwell Family Interviewaastha jainNo ratings yet

- Beck Depression InventoryDocument4 pagesBeck Depression InventoryHanaeeyeman50% (2)

- Emotional Abuse QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesEmotional Abuse Questionnairecora4eva5699100% (1)

- Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (Risb) Lec3Document9 pagesRotter Incomplete Sentence Blank (Risb) Lec3Ayesha KhalilNo ratings yet

- Manual 2day Intensive Workshop Treating Complex Trauma Internal Family Systems IfsDocument70 pagesManual 2day Intensive Workshop Treating Complex Trauma Internal Family Systems Ifscora4eva5699100% (6)

- Manual SiqDocument4 pagesManual SiqumieNo ratings yet

- MMPIDocument71 pagesMMPIK-bit MeoquiNo ratings yet

- Client Observation Skills - INGLESDocument5 pagesClient Observation Skills - INGLESAlex PsNo ratings yet

- Rotter Incomplete Sentence BlankDocument8 pagesRotter Incomplete Sentence BlankIshtiaq AhmadNo ratings yet

- 14 Worst Breakfast FoodsDocument31 pages14 Worst Breakfast Foodscora4eva5699100% (1)

- Ky For Psychiatric Disorders Shannahof PDFDocument12 pagesKy For Psychiatric Disorders Shannahof PDFSumit Kumar100% (1)

- Clinical Case Report No 2Document11 pagesClinical Case Report No 2ملک محمد صابرشہزاد50% (2)

- Projective TestsDocument3 pagesProjective TestsAlcaraz Paul JoshuaNo ratings yet

- The Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank Test: Presented by DR - Syeda Razia BukhariDocument23 pagesThe Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank Test: Presented by DR - Syeda Razia Bukhariaaminah mumtaz100% (1)

- Buck 1948Document9 pagesBuck 1948Carlos Mora100% (1)

- Observation in Clinical AssessmentDocument7 pagesObservation in Clinical AssessmentMarycynthiaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Psychology ReportDocument33 pagesClinical Psychology Reportiqra-j75% (4)

- Gerald C. Davison John M. Neale Abnormal Psychology Study Guide John Wiley and Sons 2004Document243 pagesGerald C. Davison John M. Neale Abnormal Psychology Study Guide John Wiley and Sons 2004Dejana KrstićNo ratings yet

- TAT Conflicts 1 15062020 035422pm 1 30122022 095437am 19052023 073531pm 25092023 105954amDocument10 pagesTAT Conflicts 1 15062020 035422pm 1 30122022 095437am 19052023 073531pm 25092023 105954amShanzaeNo ratings yet

- TAT Score Sheets MurrayDocument2 pagesTAT Score Sheets MurrayJennifer Caussade100% (1)

- Observational Study: Supervised by - DR SAKSHI MEHROTRA Submitted by - Ananya BhattacharjeeDocument11 pagesObservational Study: Supervised by - DR SAKSHI MEHROTRA Submitted by - Ananya BhattacharjeeManik DagarNo ratings yet

- Rorschach Ink-Blot Test: Niharika ThakkarDocument24 pagesRorschach Ink-Blot Test: Niharika ThakkarAdela Mechenie100% (1)

- Unit 3 The Thematic Apperception Test and Children S Pperception T TDocument16 pagesUnit 3 The Thematic Apperception Test and Children S Pperception T TAhmad Sameer AlamNo ratings yet

- 3-Clinical Assessment - InterviewDocument14 pages3-Clinical Assessment - Interviewsarah natasyaNo ratings yet

- Wolberg DefinitionDocument18 pagesWolberg DefinitionSwati ThakurNo ratings yet

- Assignment On BDIDocument15 pagesAssignment On BDIsushila napitNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Use Thematic Apperception Tests in Child AssessmentDocument6 pagesWhy Do We Use Thematic Apperception Tests in Child AssessmentGeraldYgayNo ratings yet

- Sentence CompletionDocument24 pagesSentence Completionlatika suryavanshiNo ratings yet

- MMPI ReportDocument18 pagesMMPI ReportRia ManochaNo ratings yet

- The Hand TestDocument2 pagesThe Hand TestRhea CaasiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Presented By: Roll No .9783Document63 pagesClinical Presented By: Roll No .9783rayscomputercollegeNo ratings yet

- General Steps of Test Construction in Psychological TestingDocument13 pagesGeneral Steps of Test Construction in Psychological Testingkamil sheikhNo ratings yet

- M Phil Clinical PsychologyDocument41 pagesM Phil Clinical PsychologyNazema_SagiNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Psychometrics & PsychodiagnosticsDocument11 pagesDifference Between Psychometrics & PsychodiagnosticsTanmay L. Joshi100% (1)

- Clinical AssessmentDocument26 pagesClinical Assessment19899201989100% (2)

- Professional Issues in Clinical PsychologyDocument5 pagesProfessional Issues in Clinical PsychologyJohn Moone100% (2)

- Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank (RISB) - Final TermDocument45 pagesRotter Incomplete Sentences Blank (RISB) - Final Termrameenshanza7No ratings yet

- RISBDocument78 pagesRISBRoxi Resurreccion57% (14)

- 16 PFDocument10 pages16 PFOdnoo Swthrt OdukaNo ratings yet

- HFDTDocument39 pagesHFDTAdrian MendozaNo ratings yet

- Writing Psychological Test ResultsDocument3 pagesWriting Psychological Test ResultsKimNo ratings yet

- Psych Case StudyDocument14 pagesPsych Case StudySmridhi Seth100% (1)

- PDF-5 The Cognitive ModelDocument24 pagesPDF-5 The Cognitive ModelChinmayi C SNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Introduction of PsychodiagnosticsDocument10 pagesChapter 1 Introduction of Psychodiagnosticsrinku jainNo ratings yet

- Ghazali Inventory TestingDocument5 pagesGhazali Inventory TestingMadiha GulNo ratings yet

- Beck Depression Inventory ScoringDocument2 pagesBeck Depression Inventory ScoringFaranNo ratings yet

- Case Report InternshipDocument10 pagesCase Report InternshipWazeerullah KhanNo ratings yet

- 21.cpsy.034 Icd-10&dsm-5Document8 pages21.cpsy.034 Icd-10&dsm-5Victor YanafNo ratings yet

- TatDocument4 pagesTatlove148No ratings yet

- TestsReport PADocument47 pagesTestsReport PAswati.meher2003100% (1)

- Defense MechanismsDocument10 pagesDefense MechanismsMonika Joseph100% (1)

- Critical Evaluation of Diagnostic SystemDocument6 pagesCritical Evaluation of Diagnostic SystemAnanya100% (1)

- Significant Variables That Influence Psychotherapy PDFDocument38 pagesSignificant Variables That Influence Psychotherapy PDFIqbal BaryarNo ratings yet

- Case 1 SchizophreniaDocument4 pagesCase 1 Schizophreniabent78100% (1)

- Priyanka K P Synopsis-1Document18 pagesPriyanka K P Synopsis-1RAJESHWARI PNo ratings yet

- Identifying Information: Psychological Assessment ReportDocument8 pagesIdentifying Information: Psychological Assessment Reportsuhail iqbal sipra100% (1)

- Foundations of Counseling and Psychotherapy: Evidence-Based Practices for a Diverse SocietyFrom EverandFoundations of Counseling and Psychotherapy: Evidence-Based Practices for a Diverse SocietyNo ratings yet

- Validity And Reliability In Statistics A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionFrom EverandValidity And Reliability In Statistics A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNo ratings yet

- Selecting The Most Appropriate Treatment For Ecah PatientDocument10 pagesSelecting The Most Appropriate Treatment For Ecah PatientCentro integral del desarrollo LogrosNo ratings yet

- WhatiscasereportDocument4 pagesWhatiscasereportRichard PhoNo ratings yet

- Lifeinglowwellness Macards-Exercise Deck-He 1 Printout 2021Document5 pagesLifeinglowwellness Macards-Exercise Deck-He 1 Printout 2021cora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Manual Defeating Habits AddictionsDocument31 pagesManual Defeating Habits Addictionscora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Manual Emdr Parts Work Treating Complex TraumaDocument73 pagesManual Emdr Parts Work Treating Complex Traumacora4eva5699100% (1)

- Somatic Based-Interventions-Day-2Document32 pagesSomatic Based-Interventions-Day-2cora4eva5699No ratings yet

- 15 Surprisingly Simple Lifestyle HacksDocument37 pages15 Surprisingly Simple Lifestyle Hackscora4eva5699No ratings yet

- 5 Brain Superfoods - by Dr. LoveDocument2 pages5 Brain Superfoods - by Dr. Lovecora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Somatic Based-Interventions-Day-1Document29 pagesSomatic Based-Interventions-Day-1cora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Therapy Coloring BookDocument35 pagesTherapy Coloring Bookcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- D B T 3 - Day Certification Supplemental Slides: Ka T El Yn Ba XT Er-Mus Ser, LCSWDocument5 pagesD B T 3 - Day Certification Supplemental Slides: Ka T El Yn Ba XT Er-Mus Ser, LCSWcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Manual Loss Resilience EfitDocument15 pagesManual Loss Resilience Efitcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Traumainformed Practice Working Complex PTSD HandoutDocument34 pagesTraumainformed Practice Working Complex PTSD Handoutcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Workbook 1 March 9Document5 pagesWorkbook 1 March 9cora4eva5699100% (1)

- How To Flourish As A PsychotherapistDocument14 pagesHow To Flourish As A Psychotherapistcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- First Call Conf PsihologieDocument1 pageFirst Call Conf Psihologiecora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Links Screening ToolsDocument2 pagesLinks Screening Toolscora4eva5699100% (1)

- How Does The Hello Brain Challenge Work?Document9 pagesHow Does The Hello Brain Challenge Work?cora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Snowflake7 PDFDocument1 pageSnowflake7 PDFcora4eva5699No ratings yet

- Textbook: English My Love Unit: Books Date: 24.04.2020Document2 pagesTextbook: English My Love Unit: Books Date: 24.04.2020Nicoleta-Maria MihețNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance (Weeks 2-3) : Lesson 2-Political IdeologiesDocument3 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance (Weeks 2-3) : Lesson 2-Political IdeologiesCatherine RodeoNo ratings yet

- Baby FacesDocument4 pagesBaby Faceskatrinasales53No ratings yet

- 7 Best Free AI Writing ToolsDocument10 pages7 Best Free AI Writing ToolssamayyNo ratings yet

- About EthiopianDocument7 pagesAbout EthiopianTiny GechNo ratings yet

- Cookery 10 Q2 W6Document11 pagesCookery 10 Q2 W6saramayrodriguez555No ratings yet

- Ethics or Moral PhilosophyDocument12 pagesEthics or Moral PhilosophyBianca GeagoniaNo ratings yet

- Independence Day: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument5 pagesIndependence Day: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogApril Grace EsmerioNo ratings yet

- Ipcrf 2022 2023 CCS 1Document11 pagesIpcrf 2022 2023 CCS 1Krisna Isa PenalosaNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 Office CompetenciesDocument48 pagesTopic 1 Office CompetenciesStunning AinNo ratings yet

- BA 203 - Reflection Paper Cenidoza, Maria LorenaDocument6 pagesBA 203 - Reflection Paper Cenidoza, Maria LorenaMaria Lorena CeñidozaNo ratings yet

- Uhv PortfolioDocument17 pagesUhv Portfoliomitali kohliNo ratings yet

- Prescriptions As Operative in The History of Psychology - Robert Watson 1971Document12 pagesPrescriptions As Operative in The History of Psychology - Robert Watson 1971Juan Hernández GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Malimono Campus Learning Continuity PlanDocument7 pagesMalimono Campus Learning Continuity PlanEmmylou BorjaNo ratings yet

- Lead RFIC EngineerDocument3 pagesLead RFIC EngineerKini FamilyNo ratings yet

- BX05 IMD MOCK POSTING User Experience Designer Co-Op Student, EDO-27152Document3 pagesBX05 IMD MOCK POSTING User Experience Designer Co-Op Student, EDO-27152themasterNo ratings yet

- LearnEnglish EfE Unit 1 Support PackDocument3 pagesLearnEnglish EfE Unit 1 Support PackAgim MuratiNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing BowDocument5 pagesCreative Writing BowJabie TorresNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia Thesis Topics RguhsDocument5 pagesAnaesthesia Thesis Topics Rguhsb0sus1hyjaf2100% (2)

- Wasim Mohammed CV NewDocument5 pagesWasim Mohammed CV Newapi-269712767No ratings yet

- Purposive Communication - Module 1Document7 pagesPurposive Communication - Module 1Angel Marie MartinezNo ratings yet

- 11.1 Indian Nursing CouncilDocument14 pages11.1 Indian Nursing CouncilValarmathi83% (6)

- Philosophy of EducationDocument2 pagesPhilosophy of EducationRo MelNo ratings yet

- Biology-Introductory Experiment: Dominant Hand +/ - 1 CM Non-Dominant Hand +/ - 1 CMDocument2 pagesBiology-Introductory Experiment: Dominant Hand +/ - 1 CM Non-Dominant Hand +/ - 1 CMPreet AnejaNo ratings yet

- List Self Finance 2018Document49 pagesList Self Finance 2018Arshi MalikNo ratings yet

- Listening 3 - Log 3 - ReportDocument5 pagesListening 3 - Log 3 - Reportmytien2004pr3No ratings yet

- Elisa GiambellucaDocument4 pagesElisa GiambellucaLeonard De LeonNo ratings yet

- Online Strategy AssignmentsDocument2 pagesOnline Strategy Assignmentsapi-665226227No ratings yet

- Preschool ObservationDocument7 pagesPreschool Observationapi-301934521No ratings yet