Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The EffectofMusicReinforcementforNon-NutritiveSuckingonNippleFeedingOfPrematureInfants PDF

The EffectofMusicReinforcementforNon-NutritiveSuckingonNippleFeedingOfPrematureInfants PDF

Uploaded by

Emaa AmooraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The EffectofMusicReinforcementforNon-NutritiveSuckingonNippleFeedingOfPrematureInfants PDF

The EffectofMusicReinforcementforNon-NutritiveSuckingonNippleFeedingOfPrematureInfants PDF

Uploaded by

Emaa AmooraCopyright:

Available Formats

Continuing Nursing Education

Posttest can be found on page 146.

The Effect of Music Reinforcement for

Non-Nutritive Sucking on Nipple Feeding

Of Premature Infants

Jayne M. Standley, Jane Cassidy, Roy Grant, Andrea Cevasco,

Catherine Szuch, Judy Nguyen, Darcy Walworth, Danielle Procelli,

Jennifer Jarred, Kristen Adams

T

he premature infants suck-

ing ability is a critical behav- In this randomized, controlled multi-site study, the pacifier-activated-lullaby sys-

ior for both survival and neu- tem (PAL) was used with 68 premature infants. Dependent variables were a) total

rological development, and number of days prior to nipple feeding, b) days of nipple feeding, c) discharge

must be sophisticated enough to sus- weight, and d) overall weight gain. Independent variables included contingent

tain independent nipple feeding. Oral music reinforcement for non-nutritive sucking for PAL intervention at 32 vs. 34 vs

feeding is a complex task for the pre- 36 weeks adjusted gestational age (AGA), with each age group subdivided into

mature infant affected by many vari- three trial conditions: control consisting of no PAL used vs. one 15-minute PAL

ables, especially the immaturity of the trial vs. three 15-minute PAL trials. At 34 weeks, PAL trials significantly shortened

neurological system and its readiness gavage feeding length, and three trials were significantly better than one trial. At

to coordinate the suck-swallow- 32 weeks, PAL trials lengthened gavage feeding. Female infants learned to nip-

breathe response. Research suggests ple feed significantly faster than male infants. It was noted that PAL babies went

that promoting non-nutritive sucking home sooner after beginning to nipple feed, a trend that was not statistically sig-

(NNS) will facilitate nipple feeding, nificant.

but more detailed investigation is

needed for development of effective

care protocols (McGrath & Braescu, essarily prolong hospitalization. This nally regulated rhythms (Goff, 1985).

2004). Feeding opportunities offered study was designed to test specific In fact, the appearance of sucking

too early may lead to negative physi- parameters of a music reinforcement behavior coincides with the first

ologic outcomes, such as apnea and protocol to promote NNS and subse- appearance of fetal brain waves. NNS

bradycardia. Delaying the initiation quent effects on duration of gavage is a reflex requiring physiologic matu-

of feeding opportunities may unnec- feeding. ration but is capable of being altered

by learning experiences (Anderson &

Vidyasagar, 1979; Bernbaum, Pereira,

Jayne M. Standley, PhD, MT-BC, is a Robert

O. Lawton Distinguished Professor of Music, Development of Watkins, & Peckham, 1983). NNS sig-

Florida State University and Tallahassee Non-Nutritive Sucking nificantly reduces distress and physio-

Memorial HealthCare, Tallahassee, FL. logical responses of premature infants

NNS is the first rhythmic behavior subjected to painful procedures (Boyle

Jane Cassidy, PhD, is Professor and Chair of in which the infant engages and is

Music Education, Louisiana State University et al., 2006; Cignacco et al., 2007;

theorized to contribute to neurologi- Mathai, Natrajan, & Rajalakshmi,

and Womans Hospital of Baton Rouge, Baton

Rouge, LA. cal development by facilitating inter- 2006; South, Strauss, South, Boggess,

Roy Grant, PhD, MT-BC, is a Retired

Professor of Music, the University of Georgia, Jennifer Jarred, MM, MT-BC, is a Music Therapist, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, and

Athens, GA. Lawnwood Regional Medical Center, Fort Pierce, FL.

Andrea Cevasco, PhD, MT-BC, is an Kristen Adams, MM, MT-BC, was a Music Therapy Intern, Florida State University and

Assistant Professor of Music Therapy, the Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare, Tallahassee, FL, at the time this article was written.

University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL. Acknowledgments: Healing HealthCare Systems and Ohmeda Medical provided equipment

Catherine Szuch, MM, MT-BC, is a Research and technical support to the study. We are indebted to them for this support. The study would not

Assistant, the University of North Carolina have been possible without extensive assistance from a great many medical personnel. Sincere

Medical Center, Chapel Hill, NC. appreciation is expressed to the nursing staff and the physicians of the four nurseries involved:

Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (Dr. Todd Patterson,

Judy Nguyen, MM, MT-BC, is a Music Neonatologist), Womans Hospital Baton Rouge Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (Dr. Steven

Therapist, Yale Childrens Hospital, New Spedale, Neonatologist), Athens Regional Medical Center Special Care Nursery (Dr. Lia Fasse,

Haven, CT. Neonatologist), and UNC Medical Center NC Childrens Hospital Newborn Critical Care Center

Darcy Walworth, PhD, MT-BC, is an (Dr. Dianne Marshall and Dr. Carl Bose, Neonatologists). Special appreciation is given to the fol-

Assistant Professor of Music Therapy, Florida lowing individuals who assisted with referrals or liaison within the hospitals: Luci Butler, MT, stu-

State University and Tallahassee Memorial dent at University of Georgia; Cori Pelletier, MT, student at University of Georgia; Jennifer

HealthCare, Tallahassee, FL. Whipple, MT-BC; and Cindy Quackenbush, RN, Kim Bloyd, RN, and Stephanie Bickis, RN, at

Danielle Procelli, MM, MT-BC, was a Music

Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare. We are most appreciative to the parents who allowed their

Therapy Intern, Florida State University and infants to participate in this study.

Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare, Tallahassee, Statement of Disclosure: The authors reported no actual or potential conflict of interest in rela-

FL, at the time this article was written. tion to this continuing nursing education article.

138 PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3

& Thorp, 2005). Therefore, the pacifi- organization. Cues are not easily read, hospital days. These studies ranged

er as a stimulant for NNS appears to and transitions in state are not from 10 to 59 participants (Pinelli &

be very important to the premature smooth. When the infant is neurolog- Symington, 2000). Pacifiers given 10

infants well-being and care in the ically immature or shows poor behav- minutes prior to nipple feeding

neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). ioral state organization at feeding increased the inactive awake state of

In the NICU, NNS opportunities opportunities, heart rate increases, the infant and decreased the total

(pacifiers) have been paired with gav- and respiratory interruptions create length of time for ingestion of nutri-

age feedings and shown to promote apneic episodes. Sucking responses tion (McCain, 1995). Due to adverse

infant development in a variety of may be weak or uncoordinated. physiological reactions to prolonged

ways. NNS lowers heart rate (McCain, Energy consumption and effort dur- feeding, the standard of care for pre-

1995; Woodson & Hamilton, 1988) ing nutritive sucking in premature mature infants usually limits a nipple

and increases oxygenation (Burroughs, infants can reduce oxygen saturation feeding opportunity to 30 minutes

Asonye, Anderson-Shanklin, & and can expend calories resulting in (Gardner, Garland, Merenstein, &

Vidyasagar, 1978). It also increases weight loss (Hill, 1992). Prior to 34 Lubchenco, 1997). After that time,

weight gain of the infant even when weeks adjusted gestational age (AGA), the remaining nutrition is given by

nutritional intake is controlled (Field et gavage feeding (oral-gastric [OG] or gavage tube. Strengthening the suck

al., 1982; Kanarek & Shulman, 1992). naso-gastric [NG] tube) is necessary and increasing the rate of nutritional

It is theorized that NNS calms but stressful for the premature infant. intake is frequently a step to reducing

infants and facilitates lower activity the length of a nipple feeding

levels, resulting in energy conserva- episode. Most infants who can

tion and subsequent weight gain. This Development of Feeding demonstrate adequate oral intake of

theory is supported by the finding Ability nutrition within the 30-minute inter-

that NNS with gavage feeding results val are discharged within 24 hours

in increased duration of inactive alert The development of sucking abili- (McGrath & Braescu, 2004).

state and faster return to and ty for feeding is correlated with neu-

increased length of quiet sleep rological maturity, but not gestational

(DiPietro, Cusson, Caughy, & Fox, age or birth weight (McCain, 1992; Effects of Music Therapy

1994; Gill, Behnke, Conlon, McNeely, Medoff-Cooper & Gennaro, 1996).

& Anderson, 1988; Goff, 1985; Specifically, higher sucking pressure, In the NICU

McCain, 1992, 1995). Other benefits number of sucking bursts, and dura- Research has shown that a variety

of NNS during gavage feeding include tion of pauses between bursts at 34 of stimulation techniques adminis-

decreased length of hospital stay and weeks gestational age correlate with tered to pre-term infants can offset

decrease in necessity for tube feedings higher psychomotor scores at 6 some adverse neurological effects of

(Bernbaum et al., 1983; Field et al., months of age. Palmers (1993) assess- premature birth and the adverse conse-

1982). A meta-analysis on research ment of premature infants consistent- quences of prolonged hospitalization

assessing clinical outcomes of offering ly found an immature pattern of suck- (Britt & Myers, 1994; Gomes-Pedro et

NNS during gavage feeding found it ing, consisting of 3 to 5 sucks in a al., 1995; Harrison, 1985; Oehler, 1993;

decreased length of hospitalization by burst followed by a pause to breathe. Rauh et al., 1987). Music, particularly,

an average of 6.3 days and allowed More mature, term infants sucked 10 has been effective with premature

premature infants to begin bottle to 30 times in a prolonged burst and infants in increasing weight gain,

feeding an average of 2.9 days sooner alternated breathing with sucking. reducing observed stress behaviors,

(Schwartz, Moody, Yarndi, & Mature nutritive sucking coordina- reducing length of hospitalization by

Anderson, 1987). A more recent meta- tion would seem to be a highly up to 11 days for female (not male)

analysis using NNS with gavage feed- important goal for premature infants infants, and increasing oxygen satura-

ing also found a significant decrease for a variety of health, growth, and tion levels for short periods of time

in length of stay (Pinelli & developmental reasons. (Caine, 1992; Cassidy & Standley,

Symington, 2005). The coordinated suck-swallow- 1995; Chapman, 1979; Standley, 1998;

breathe response develops around the Standley & Moore, 1995; Whipple,

34th week of gestation and becomes 2008). Survey results show that 72% of

Feeding Problems of the possible when myelination of the U.S. NICUs play music for premature

medulla has occurred (McGrath & infants (Field, Hernandez-Reif, Feijo, &

Premature Infant Braescu, 2004). It is a precursor to Freedman, 2006).

The well, term infant is born capa- nutritive sucking ability and nipple Auditory capability is an early, dis-

ble of feeding with a coordinated, feeding. Medical procedures, such as criminative ability of the fetus

suck-swallow-breathe response that intubation, can delay the develop- (Cheour-Luhtanen et al., 1996). It has

occurs without detrimental changes ment of a coordinated sucking pat- been documented that as early as 18

in heart rate or respiratory capabili- tern in premature infants. The transi- weeks gestational age, loud sounds

ties. Further, the term infants behav- tion from gavage to nipple feeding is cause the fetal heart rate to increase,

ioral states are organized and easily often difficult for the premature and at 25 weeks, the major structures

read by caregivers. In the presence of infant, and sometimes long-term of the ear are essentially in place. At

food, crying due to hunger quickly problems develop, such as nipple 25 to 27 gestation weeks, most fetuses

moves to a state of alertness with the aversion or aversion to oral feeding begin to respond inconsistently to

infant focused for feeding. This occurs (Palmer, 1993). sound by moving or kicking (Cheour-

smoothly without detrimental physi- Oral feeding skill can be assisted Luhtanen et al., 1996). At 30 to 35

ological changes (McCain, 1992). through NNS. A Cochrane review of weeks, the infant hears maternal

Unlike the term infant, the prema- 19 studies on benefits of pacifiers with sounds, responds to these sounds,

ture infant is neurologically immature premature infants found that NNS and begins to discriminate among

and has impaired behavioral state significantly decreased number of speech sounds, particularly with

PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3 139

The Effect of Music Reinforcement for Non-Nutritive Sucking on Nipple Feeding of Premature Infants

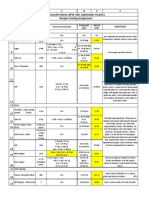

regard to pitch and rhythm Table 1.

(Lecanuet, Granier-Deferre, & Busnel, Design and Number of Subjects by Gender

1995). The premature infant ready for

transition to nipple feeding has the PAL Trials by Gestational Age Male n Female n Total n

ability to hear, discriminate, and ben- 32 Weeks AGA

efit from auditory input.

At term birth, females are more No-contact control 4 4 8

developed with regard to hearing 1 PAL trial 4 4 8

(Cassidy & Ditty, 2001), have better

tactile and oral sensitivity, and are 3 PAL trials 4 4 8

more responsive to smiling, sweet 34 Weeks AGA

tastes, talking, eye-to-eye contact, and

the pacifier. Cerebral blood flow in No-contact control 4 4 8

girls is significantly lower than in 1 PAL trial 4 4 8

males. Male infants demonstrate

more startles, more muscle activity, 3 PAL trials 3 3 6

and more physical strength. With 36 Weeks AGA

regard to auditory capability at birth,

male infants actually have shorter No-contact control 3 4 7

cochlea, fewer hair cells, and less 1 PAL trial 4 4 8

response to aural stimuli. Female

infants hear high frequencies better 3 PAL trials 3 4 7

than males, which is particularly Total n 33 35 68

advantageous when listening to

music with its wide range of frequen- Note: PAL = pacifier-activated lullaby.

cies (Cassidy & Ditty, 2001).

A meta-analysis of studies using

music in the NICU demonstrated sig- Purpose of Study weeks AGA. These age groupings were

nificant clinical benefits across a vari- chosen for the following reasons:

ety of physiological and behavioral The purpose of this study was to NICU personnel disagree on when to

measures (Standley, 2002). Linguistics ascertain the effect of the pacifier-acti- intervene to begin oral feeding train-

research showed that lullabies of all vated lullaby system (PAL) on cessa- ing. Some believe the infant is too

cultures combine language informa- tion of gavage feeding of premature neurologically immature to benefit

tion and use calming, rhythmic stim- infants due to oral feeding achieve- from intervention prior to 34 weeks.

uli. Because it is desirable to reduce ment. Cessation of gavage feeding Others believe that starting interven-

stress and calm premature infants in was operationally defined as the date tion before 34 weeks facilitates the

the NICU and because infants leaving of the last gavage feeding given by infants transition from gavage feed-

the womb too early are missing lan- NICU personnel. Specific aims were ing at 34 weeks. Infants still not nip-

guage input from their mothers voic- to: ple feeding at 36 weeks are considered

es, lullabies are the music of choice Determine whether gender affects seriously delayed, and benefits of typ-

for pacification and language devel- achievement of nipple feeding ical NICU interventions are ques-

opment of premature infants skills resulting from PAL usage. tioned. Therefore, it was decided to

(Standley, 1998, 2003a). Determine whether number of test intervention at 34 weeks AGA

Prior studies have shown that con- PAL trials (0, 1, or 3) affect nipple and the two weeks before and after

tingent music (such as pacifier-activat- feeding skills. this midpoint. One trial vs. three tri-

ed lullabies [PALs]) increased pacifier Determine whether age at PAL als were contrasted because prior

sucking rate of premature infants intervention (32, 34, or 36 weeks research with the PAL showed that

more than 2.5 times (Standley, 2000) AGA) affects nipple feeding skills. infants learned to suck frequently

and also increased subsequent feeding enough to sustain the music in one

rate (Standley, 2003b). Infants given trial and improved their oral feeding

one PAL trial 30 minutes prior to a late Method rate after only one trial. It was

afternoon oral feeding attempt signifi- unknown whether only one trial

cantly increased the amount of nutri- Participants and Design might affect the number of days until

tion ingested/minute when compared The design of this study was a 3x3- independent nipple feeding was

to their feeding rate during a morning block design contrasting number of achieved, and three trials seemed suf-

oral feeding attempt. Cevasco and repetitions of PAL trials by gestational ficient to note changes in nipple feed-

Grant (2005) used the PAL in multiple age at the beginning of the trial. Table ing benefits if they would occur due

trials with 62 premature infants and 1 details the design and number of to PAL intervention.

found strong trends for increased participants in each group. Following Dependent variables were:

weight gain with increasing age and referral and receipt of informed con- Days prior to nipple feeding com-

PAL trials, though these increases were sent, premature infants who were puted by counting days from

not substantial enough to be statisti- born prior to 32 weeks gestational age birth to date of last OG/NG feed

cally significant. Little other research as measured by Dubowitz criteria recorded on each infants daily

exists to determine the most appropri- were randomly assigned by gender to chart by nurses.

ate age to begin music reinforcement three intervention groups (no-contact Days of nipple feeding prior to

for NNS or the number of trials neces- control, 1 PAL trial, or 3 PAL trials) discharge computed by counting

sary to facilitate nipple feeding of pre- and further divided into time of inter- days from last OG/NG feed to dis-

mature infants. vention occurring at 32, 34, or 36 charge date. (Note: The two meas-

140 PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3

ures of feeding days when added piration or apnea, flushing or effects and were especially recorded to

together equal length of hospital- mottling of skin, tremors, startles, reduce alerting musical stimuli.

ization.) flayed fingers or hand in stop Recording criteria included no

Discharge weight recorded on the position, eye rolling or floating, changes in tempo, no changes in vol-

dis whimpering, hiccoughing, spit- ume level, no key changes, and no

Weight gain computed by sub- ting up, and gagging. No such changes in accompaniment style. The

tracting birth weight from dis- responses were noted in response music was presented at 65 dB (Scale

charge weight. to the PAL. C) via small speakers placed binaural-

Participants were referred for the Infants were not held but ly in the incubator above the infants

study by medical staff when the remained in the crib or incubator head. The music sustained for 10 sec-

infant was deemed able to tolerate lying on their backs or sides to onds and subsequently shut off unless

two simultaneous modes of stimula- reduce additional stimulation. reactivated by another suck, therefore

tion (pacifier and auditory stimula- PAL pacifier pressure = one bar on making the presentation of music

tion) and if still gavage feeding at machine menu to begin training. stimuli contingent on the sucking

time of study. Upon referral, the Treatment duration = maximum behavior of the infant. All infants

infant was randomly assigned to a of 15 minutes opportunity for were lying on their backs or sides dur-

trial condition by age group. If the sucking. ing PAL trials. Although it did not

infant achieved nipple feeding prior Discontinue when infant rejects occur, provisions were made in the

to attaining the randomly assigned pacifier twice or falls asleep. protocol to discontinue use of the

age, the infant was not enrolled in the Researchers were not a part of the pacifier if signs of infant stress were

study. The protocol for the study medical staff but were professionals observed. PAL settings allowed music

excluded infants who: who came to the NICU at the same reinforcement after one trigger (suck)

Were intubated at the time of the time each day to run PAL trials. and at the lowest amount of pressure

study. Medical staff that made referrals for change (weakest suck).

Had severe abnormalities that the study and who determined readi- The experimental infants received

affected ability to suck, feed, or ness for discharge were blind as to either one 15-minute trial with the

learn, including abnormalities of whether the infants were subsequent- PAL or three trials within a 5-day peri-

the oral cavity, hydrocephalus, ly enrolled in the study or to their od at the time of their achieving the

Down syndrome, and significant random assignment of intervention randomly assigned age and still rely-

neurological disorders, such as group. Many infants received PAL ing on gavage feeding. PAL trials

intraventricular hemorrhage of clinical treatment by the research occurred at the same time each day

levels III or IV, periventricular team, but medical personnel were not between 4:00 to 5:00 p.m. and were

leukomalacia, or hypoxic- aware whether a specific infants PAL not given in relationship to feeding

ischemic encephalopathy. usage occurred for the purpose of data times of individual participants. A

Had positive results on screen for collection for this study. Participants prior study that had compared morn-

illegal drug use by the mother. in this study received only the num- ing and afternoon feeding rates had

Criteria for referral included the ber of PAL trials specified in the group shown the PAL intervention to be

infant: cohort to which they were randomly effective in this time frame (Standley,

Was determined to be able to tol- assigned. 2003b). The no-contact control

erate two simultaneous modes of groups met the same criteria but

stimulation (pacifier and auditory Sites received no PAL intervention. Data

stimulation). The study was conducted by music were recorded by the researchers from

Had no indication of infection therapy researchers from four major the nurses notes. Nurses were blind

requiring quarantine. universities at four critical care nurs- to the purpose of the study and to

Was ready to begin some OG eries in regional hospitals in the infants status in the study. Data

feeds. southeast. It was approved by the included date of birth, birth weight,

Protocol was as follows: Human Subjects Committees at each gestational age by Dubowitz criteria at

Medical staff of the NICU made university and by the Institutional birth, date of last gavage (naso-gastric

referral for PAL. Review Boards at each hospital. The or oral-gastric) feeding, discharge

PAL was presented at least a half sites included Site A, a 40-bed Level III date, and discharge weight.

hour prior to a scheduled feeding. NICU; Site B, a 68-bed Level III NICU;

The nurse caring for the child Site C, a 10-bed special care nursery;

gave permission on the day the and Site D, a 48-bed Level III newborn

Results

PAL was presented, affirming that critical care center. Because some sites completed

additional stimulation was appro- many more participants than others,

priate for the child at that time. Procedure data were analyzed by site to deter-

(Sometimes infants had had a Contingent music was delivered mine if location affected results.

stressful day, and further stimuli via the PAL (Standley, 2000). With Tables 2 and 3 show birth weight and

were contraindicated.) this equipment, an infant sucks on a gestational age at birth by site and

Music was located adjacent to and Wee Soothie pacifier fitted with an gender.

outside the crib or incubator with adaptor housing a computer chip that SPSS Two-Way Analysis of birth

decibel level averaging 60 to 65 activates a CD player outside the gestational age by gender and site

dB measured at infants ear (Scale incubator. The music stimulus was a showed no differences for gestational

C, 1 volume bar on PAL machine). continuous selection of lullabies sung age at birth among sites (F = 2.522, df

The protocol stipulated that the by a young female with minimal = 3, p = 0.066) or for gender by site (F

use of PAL would be discontinued accompaniment. The lullabies were = 1.286, df = 3, p = 0.288). Overall, the

if signs of infant distress were traditional lullabies selected by the gestational age at birth for all males

observed, including irregular res- music therapists for their soothing was significantly earlier than that for

PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3 141

The Effect of Music Reinforcement for Non-Nutritive Sucking on Nipple Feeding of Premature Infants

Table 2. all females (F = 5.529, df = 1, p =

Mean Birth Weight in Kilograms by Site and Gender 0.022). SPSS Two-Way Analysis of

birth gestational age by randomly

Site Male Female Overall Mean assigned age groups at time of study

and by number of trials showed no

Site A (n = 28) 1.0758 1.0824 1.0796

significant difference among PAL tri-

Site B (n = 18) 1.296 1.1572 1.165 als groups (F = 2.016, df = 2, p = 0.142)

and also showed that infants random-

Site C (n = 18) 1.2580 1.3896 1.3238*

ly assigned to the 36-week age group

Site D (n = 4) 1.2583 0.5530 1.0820 at time of study were born significant-

ly earlier than infants in other age

Overall Mean Weight 1.1949 1.1655 1.1798 groups (F = 4.11, df = 2, p = 0.021).

Notes: N = 68; no significant difference by gender. This was predictable and inevitable

*p < 0.05, Site C babies significantly higher in birth weight than Site A and Site D because infants born earlier have

babies. more difficulty learning to nipple feed

and are more likely to still be gavage

feeding at 36 weeks adjusted gesta-

tional age.

Table 3. SPSS Two-Way Analysis of birth

Mean Gestational Age at Birth by Site and Gender weight data by gender and site

showed no significant difference by

Site Male Female Overall Mean gender (F = 2.342, df = 1, p = 0.131)

but differences by site. Infants from

Site A (n = 28) 29.0 28.5 28.7 Site C had significantly higher birth

Site B (n = 18) 29.6 28.9 29.3 weights (F = 2.910, df = 3, p = 0.042)

than the infants at Site A (p = 0.014)

Site C (n = 18) 30.1 30.0 30.1 and at Site D (p = 0.040). SPSS Two-

Site D (n = 4) 30.3 26.0 29.2 Way Analysis of birth weight data by

age at study and by trials showed no

Overall Mean Weight 29.6* 28.9 29.2 significant differences among trials (F

= 1.345, df = 2, p = 0.270). Again, as

Notes: N = 68; no significant difference by site. expected, the infants in the 36-week

*p < 0.05, males significantly older than females at birth. age group at the time of the study

were born with significantly lower

birth weights than those in all other

age groups (F = 6.867, df = 2, p =

Table 4. 0.002).

Mean Subject Characteristics by Age at Study and by PAL Trials Because infant characteristics data

showed few statistical differences by

Birth Age in site or gender, data were pooled for

PAL Trials by Gestational Age Birthweight in Kg Gestational Weeks subsequent analyses. Table 4 shows

32 Weeks AGA pooled birthweight and gestational

age at birth data for participants by

Control (n = 8) 1.39 30.4 age at study and trials.

1 PAL trial (n = 8) 1.26 29.3 Data for each of the four depend-

ent variables were subjected to Two-

3 PAL trials (n = 8) 1.27 29.6 Way Analyses of Variance for compar-

32-week total 1.31 29.8 ison by gender and trials. Females (M

= 7.03) nipple fed significantly longer

34 Weeks AGA prior to discharge than did males (M =

Control (n = 8) 1.09 28.9 5.70, p < 0.0001). This means they

succeeded in nipple feeding sooner

1 PAL trial (n = 8) 1.25 29.3 than males. This result was expected

3 PAL trials (n = 6) 1.42 30.6 because female premature infants

generally show faster maturation

34-week total 1.24 29.5 than male infants (Standley, 2003a).

36 Weeks AGA There were no other gender differ-

ences on any of the four dependent

Control (n = 7) 0.91 28.1 variables or by number of trials.

1 PAL trial (n = 8) 0.94 27.9 Analysis by site showed that

infants at Site A were discharged at

3 PAL trials (n = 7) 1.12 29.3 significantly lower weights than other

36-week total 1.18 28.4 sites (F = 14.919, df = 3, 60, p =

0.0001), but they were also born at

Note: N = 68. slightly lower birth weights than the

other participants. Subsequently,

their weight gain was also significant-

ly less while in the hospital (F = 4.883,

142 PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3

Table 5.

Results: Means and (Standard Deviations) by PAL Trial Groups and Age at Study

PO Days to

PAL Trials by Gestational Age Gavage Days Discharge Discharge Weight Weight Gain

32 Weeks AGA

Control (n = 8) 33.25* 6.63 2.1974 k 0.8025 k

(8.50) (3.74) (0.4086) (0.2523)

1 PAL trial (n = 8) 46.75 5.13 2.2759 k 1.0193 k

(17.33) (2.36) (0.5998) (0.5920)

3 PAL trials (n = 8) 48.50 6.00 2.4533 k 1.1829 k

(15.89) (3.59) (0.5670) (0.5033)

34 Weeks AGA

Control (n = 8) 58.88 10.25 2.5100 k 1.4233 k

(13.10) (12.19) (0.3962) (0.4772)

1 PAL trial (n = 8) 46.88* 3.88 2.2816 k 1.0340 k

(14.67) (2.75) (0.3636) (0.4245)

3 PAL trials (n = 6) 35.17* 4.17 2.1808 k 0.7597 k

(8.40) (1.83) (0.1776) (0.3073)

36 Weeks AGA #

Control (n = 7) 67.71 6.711 2.2514 k 1.3487 k

(13.39) (3.90) (0.4853) (0.4518)

1 PAL trial (n = 8) 68.88 6.50 2.2426 k 1.3049 k

(25.34) (2.45) (0.2831) (0.3100)

3 PAL trials (n = 7) 64.71 7.86 2.6280 k 1.5097 k*

(21.48) (3.53) (0.6168) (0.6055)

Notes: N = 68.

*p < 0.05, significantly different within age group, PAL trials significantly shortened length of gavage feeding for 34-week babies, and

3 trials were significantly better than 1 trial. PAL trials significantly increased length of gavage feeding for 32-week babies.

# p < 0.05, significantly different across age groups, all 36-week AGA infants were gavage fed significantly longer than the other two

groups. Overall, 36-week AGA infants gained significantly more weight than the other age groups.

df = 3, 60, p = 0.004). Overall, data significant (F = 2.758, df = 4, p = number of PAL trials affected benefits.

showed little difference among vari- 0.036). No other comparisons were PAL trials significantly shortened

ables by site, and gender was equal- significant. length of gavage feeding for 34-week

ized in the random assignment Analysis of total weight gain from babies, and three trials were signifi-

among groups; therefore, it was birth to discharge was significant for cantly better than one trial. PAL trials

assumed these groupings did not age at study (F = 4.629, df = 2, p = significantly increased length of gav-

affect overall results of PAL trials, and 0.014). Tukey HSD post hoc analysis age feeding for 32-week babies. These

data were pooled for further analyses. showed that the 36-week AGA infants results would indicate that the PAL is

Results for each of the four gained significantly more weight than most effective when introduced at 34

dependent variables were subjected to the other two age groups, but this was gestational weeks, the point in time

Two-Way Analyses of Variance for expected because they were born when most infants are deemed neuro-

comparison by age at study and num- smaller and stayed in the hospital logically ready to nipple feed (McGrath

ber of PAL trials. Table 5 shows means, longer. & Braescu, 2004).

standard deviations, and significance Analysis of weight gain for age at The sample was very small in the

comparisons among means using study by PAL trials was significant (F = 36-week age group receiving three PAL

Tukey post hoc analysis. 2.739, df = 4, p = 0.037). Tukey HSD post trials due to the rarity of infants meet-

Analysis of gavage feeding days hoc analysis showed no significance for ing criteria for continued inclusion in

showed significance for age at study specific age by trial comparisons. the study. Specifically, most infants

(F = 14.137, df = 2, p = 0.0001). Tukey enrolled at 36 weeks who were not nip-

HSD post hoc analysis showed that all ple feeding began to do so after one

36-week AGA infants took significant- Discussion PAL trial. Therefore, it was impossible

ly longer to oral feed than the 32 or to fulfill the planned cohort for the 36-

34-week infants, and three PAL trials The purpose of this study was to week, three-trial group. This age group

shortened the interval, but not signif- ascertain whether the PAL benefitted deserves further study with a design

icantly so. Analysis of gavage feeding infant transition from gavage to nipple that does not require multiple PAL tri-

days for age at study by trials was also feeding, and if age of presentation or als at this gestational age.

PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3 143

The Effect of Music Reinforcement for Non-Nutritive Sucking on Nipple Feeding of Premature Infants

Overall, the results of this PAL pro- presentation and multiple trials had non-crying, preterm neonates. Research in

Nursing and Health, 1(2), 69-75.

tocol by age at study and trials do not never been attempted. This protocol Caine, J. (1992). The effects of music on the selected

demonstrate significant weight gain proved effective in significantly short- stress behaviors, weight, caloric and formula

benefits except those related to longer ening gavage days for 34-week AGA intake, and length of hospital stay of premature

stay in the hospital. Similar to findings infants. Future research must be exact and low birth weight neonates in a newborn

intensive care unit. Journal of Music Therapy,

by Cevasco and Grant (2005), there are in assessing and comparing specific 28(4), 180-192.

trends that may warrant future protocol parameters to improve care Cassidy, J., & Ditty, K. (2001). Gender differences

research with revised protocols and procedures. Much more research in among newborns on a transient otoacoustic

design. Cevasco and Grant (2005) this area is warranted. emissions test for hearing. Journal of Music

Therapy, 38(1), 28-35.

showed increasing weight gain with Cassidy, J., & Standley, J. (1995). The effect of music

increasing age and increasing PAL listening on physiological responses of prema-

usage; however, this study demonstrat- Clinical Implications ture infants in the NICU. Journal of Music

ed such results in the 36-age group Therapy, 37(4), 208-227.

A PAL intervention can significant- Cevasco, A., & Grant, R. (2005). Effect of the pacifier

only. This studys results for weight ly shorten gavage feeding days and activated lullaby on weight gain of premature

gain by age may be primarily due to length of hospitalization for premature infants. Journal of Music Therapy, 42(2), 123-

36-week infants longer stay in the infants when used at the specific gesta- 139.

NICU associated with necessity for tion age of 34 weeks. The intervention

Chapman, J.S. (1979). Influence of varied stimuli on

development of motor patterns in the prema-

completion of three trials prior to dis- protocol should begin with a PAL treat- ture infant. In G. Anderson & B. Raff (Eds.),

charge. ment of 15 minutes approximately 30 Newborn behavioral organization: Nursing

It should be noted that there were minutes prior to a feeding trial and research and implications (pp. 61-80). New

several confounding factors in this should continue daily until the infant

York: Alan Liss.

Cheour-Luhtanen, M., Alho, K., Sainio, K., Rinne, T.,

study. Every infant from whom con- is independently nipple feeding. The Reinikainen, K., Pohjavuouri, M., ... Naatanen,

sent was received and who was ran- lullaby selected for reinforcement of R. (1996). The ontogenetically earliest discrimi-

domly assigned to the 32 to 33-week sucking should be in the native lan- native response of the human brain.

age group completed participation in Psychophysiology, 33, 478-481.

guage of the infants family if possible. Cignacco, E., Hamers, J., Stoffel, L., van Lingen, R.,

the project. However, some assigned to In this way, the infant will be receiving Gessler, P., McDougall, J., & Nelle, M. (2007).

the 34 to 35-week age group and many critical language input while being The efficacy of non-pharmacological interven-

more assigned to the 36 to 37- week reinforced for sucking. The protocol tions in the management of procedural pain in

age group graduated and failed to used in this study is recommended.

preterm and term neonates. A systematic liter-

ature review. European Journal of Pain, 11(2),

complete the study because they began 139-152.

nipple feeding or were discharged Criteria for Referral DiPietro, J., Cusson, R., Caughy, M., & Fox, N. (1994).

before conclusion of trials. Infant is determined to be able to Behavioral and physiologic effects of nonnutri-

Independent feeding is one main crite- tolerate two simultaneous modes

tive sucking during gavage feeding in pre-term

infants. Pediatric Research, 36(2), 207-214.

rion for discharge, and infants who of stimulation (pacifier and audi- Field, T., Hernandez-Reif, M., Feijo, L., & Freedman,J.

began to feed well were immediately tory stimulation). (2006). Prenatal, perinatal and neonatal stimu-

sent home. Since the research design Infant has no severe abnormali- lation: A survey of neonatal nurseries. Infant

required that some infants at 34 or 36 Behavior and Development, 29(1), 24-31.

ties that affect ability to suck/feed Field, T., Ignatoff, E., Stringer, S., Brennan, J.,

weeks AGA still need gavage feeding or to learn, including abnormali- Greenberg, R., Widmayer, S., & Anderson, G.

throughout three PAL trials across 3 to ties of the oral cavity, hydro- (1982). Nonnutritive sucking during tube feed-

5 days, a bias for length of stay was cre- cephalus, Down syndrome, signif- ings: Effects on preterm neonates in an inten-

ated for the two older groups. Some sive care unit. Pediatrics, 70(3), 381-384.

icant neurological disorders (PVL, Gardner, S.L., Garland, K.R., Merenstein,S. L., &

participants excelled at acquiring nip- IVH, HIE). Lubchenco, L.O. (1997). The neonate and the

ple feeding skills and left before com- Infant has no indication of infec- environment Impact on development. In G.B.

pleting the research trials. tion requiring quarantine. Merenstein & S.L. Gardner (Eds.). Handbook of

The PAL shows some potential for neonatal intensive care (4th ed.) (pp. 564-608).

Infant is not on ventilator or St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

facilitating nipple feeding, and contin- CPAP. Gill, N., Behnke, M., Conlon, M., NcNeely, J., &

ued research is warranted to further Infant is ready to begin some OG Anderson, G. (1988). Effect of nonnutritive

refine the PAL intervention protocols. feeds. sucking on behavioral state in preterm infants

Nipple feeding is necessary for dis- before feeding. Nursing Research, 37(6), 347-

350.

charge. Infants begin training at 34 Goff, D.M. (1985). The effects of nonnutritive sucking

weeks AGA, and a few succeed imme- References on state regulation in pre-term infants.

diately. However, very low birth Anderson, G., & Vidyasagar, D. (1979). Development Dissertation Abstracts International, 46(8-B),

weight infants and those intubated for of sucking in premature infants from 1 to 7 days 2835.

longer periods have great difficulty post birth. Birth Defects: Original Article Series, Gomes-Pedro, J., Patricio, M., Carvalho, A.,

15(7), 145-171. Goldschmidt, T., Torgal-Garcia, F., & Monteiro,

with this task. Many infants remain Bernbaum, J., Pereira, G., Watkins, J., & Peckham, G. M. (1995). Early intervention with Portuguese

hospitalized solely due to inability to (1983). Nonnutritive sucking during gavage mothers: A 2-year follow-up. Journal of

oral feed. At a U.S. average NICU cost feeding enhances growth and maturation in Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics,

premature infants. Pediatrics, 71(1), 41-45. 16(1), 21-28.

of approximately $2000/day, this can Harrison, L. (1985). Effects of early supplemental

Boyle, E., Freer, Y., Khan-Orakzai, A., Watkinson, M.,

be an expensive and depressing period Wright, E., Ainsworth, J., & McIntosh, N. (2006). stimulation programs for premature infants:

for the family awaiting discharge Sucrose and non-nutritive sucking for the relief Review of the literature. Maternal-Child Nursing

(Standley, 2003a). Interventions that of pain in screening for retinopathy: A ran- Journal, 14(2), 69-90.

can speed up this process without domised controlled trial. Archives in Disease in Hill, A. (1992). Preliminary findings: A maximum oral

Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 91(3), feeding time for premature infants, the relation-

physiologic harm to the infant are 166-168. ship to physiological indicators. Maternal-Child

highly desired. In prior research, one Britt, G., & Myers, B. (1994). The effects of Brazelton Nursing Journal, 20(2), 81-92.

PAL intervention proved to be highly intervention: A review. Infant Mental Health, Kanarek, K., & Shulman, D. (1992). Non-nutritive

effective in increasing sucking rate and 15(3), 278-292. sucking does not increase blood levels of gas-

Burroughs, A., Asonye, U., Anderson-Shanklin, G., & trin, motilin, insulin and insulin-like growth factor

subsequent feeding rate. However, a Vidyasagar, D. (1978). The effect of nonnutritive 1 in premature infants receiving enteral feed-

specific PAL protocol testing age of sucking on transcutaneous oxygen tension in ings. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica, 81, 974-

977.

144 PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3

Lecanuet, J., Granier-Deferre, C., & Busnel, M. Palmer, M.M. (1993). Identification and management Standley, J. (1998). The effect of music and multi-

(1995). Human fetal auditory perception. In J.P. of the transitional suck pattern in premature modal stimulation on physiologic and develop-

Lecanuet, W.P. Fifer, N.A. Krasnegor, & W.P. infants. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal mental responses of premature infants in

Smotherman, (Eds.), Fetal development: A psy- Nursing, 7(1), 66-75. neonatal intensive care. Pediatric Nursing,

chobiological perspective (pp. 239-262). Pinelli, J., & Symington, A. (2000). How rewarding can 24(6), 532-538.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. a pacifier be? A systematic review of non-nutri- Standley, J. (2000). The effect of contingent music to

Mathai, S. Natrajan, N., & Rjalakshmi, N. (2006). A tive sucking in pre-term infants. Neonatal increase non-nutritive sucking of premature

comparative study of nonpharmacological Network, 19(8), 4-8. infants. Pediatric Nursing, 26(5), 493-499.

methods to reduce pain in neonates. Indian Pinelli, J., & Symington, A. (2005). Non-nutritive suck- Standley, J. (2002). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of

Pediatrics, 43(12), 1070-1075. ing for promoting physiologic stability and nutri- music therapy for premature infants. Journal of

McCain, G. (1992). Facilitating inactive awake states tion in pre-term infants. Cochrane Database of Pediatric Nursing, 17(2), 107-113.

in pre-term infants: A study of three interven- Systematic Reviews, 2005(4): CD001071. Standley, J. (2003a). Music therapy with premature

tions. Nursing Research, 41(3), 157-160. Rauh, V., Nurcombe, B., Achenbach, T., & Howell, C. infants: Research and developmental interven-

McCain, G. (1995). Promotion of pre-term infant nip- (1987). The mother-infant transaction program: tions. Silver Spring, MD: American Music

ple feeding with non-nutritive sucking. Journal An intervention for the mothers of low-birth- Therapy Association.

of Pediatric Nursing, 10(1), 3-8. weight infants. In N. Gunzenhauser (Ed.), Infant Standley, J. (2003b). The effect of music-reinforced

McGrath, J., & Braescu, A. (2004). State of the sci- stimulation: For whom, what kind, when, and non-nutritive sucking on feeding rate of prema-

ence: Feeding readiness in the preterm infant. how much? Skillman, NJ: Johnson & Johnson ture infants. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 18(3),

Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 18(4), Baby Products. 169-173.

353-368. Schwartz, R., Moody, L., Yarndi, H., & Anderson, G. Standley, J., & Moore, R. (1995). Therapeutic effects

Medoff-Cooper, B., & Gennaro, S. (1996). The corre- (1987). A meta-analysis of critical outcome vari- of music and mothers voice on premature

lation of sucking behaviors and Bayley Sclaes ables in non-nutritive sucking in pre-term infants. Pediatric Nursing, 21(6), 509-512, 574.

of Infant Development at six months of age in infants. Nursing Research, 36(5), 292-295. Whipple, J. (2008). The effect of music-reinforced non-

VLBW infants. Nursing Research, 45(5), 291- South, M., Strauss, R., South, Al. Boggess, J., & nutritive sucking on state of preterm, low birth-

296. Thorp, J. (2005). The use of non-nutritive suck- weight infants experiencing heelstick. Journal of

Oehler, J. (1993). Developmental care of low birth ing to decrease the physiologic pain response Music Therapy, 45(3), 227-272.

weight infants. Advances in Clinical Nursing during neonatal circumcision: A randomized Woodson, R., & Hamilton, C. (1988). The effect of

Research, 28(2), 289-301. controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics nonnutritive sucking on heart rate in preterm

and Gynecology, 193(2), 537-542. infants. Developmental Psychobiology, 21(3),

207-213.

PEDIATRIC NURSING/May-June 2010/Vol. 36/No. 3 145

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hazen Williams EquationDocument5 pagesHazen Williams Equationprabhjot123100% (1)

- 2014 Annual Report GeneaDocument120 pages2014 Annual Report GeneaPeterDavidNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology NSAID Induced UGIB Gouty Arthritis and Gouty NephropathyDocument2 pagesPathophysiology NSAID Induced UGIB Gouty Arthritis and Gouty NephropathyghellersNo ratings yet

- Repro MindmapDocument3 pagesRepro MindmapghellersNo ratings yet

- Nursing Diagnosis Fvd2Document2 pagesNursing Diagnosis Fvd2ghellersNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Fluid Volume Deficit R/T Active Fluid Loss (Increased Urine Output)Document9 pagesNursing Care Plan: Fluid Volume Deficit R/T Active Fluid Loss (Increased Urine Output)ghellersNo ratings yet

- Erik Eriksons Psycho Social Development TheoryDocument23 pagesErik Eriksons Psycho Social Development TheoryRaven Dave AtienzaNo ratings yet

- MCST Stimuli-CompressedDocument10 pagesMCST Stimuli-Compressedapi-470437967No ratings yet

- El TB 04Document2 pagesEl TB 04Fayyaz NadeemNo ratings yet

- API BGD DS2 en Excel v2 4685979Document339 pagesAPI BGD DS2 en Excel v2 4685979Areesha KamranNo ratings yet

- Igcse: Definitions & Concepts of ElectricityDocument4 pagesIgcse: Definitions & Concepts of ElectricityMusdq ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- A Shew Recipe Costing XLSX 2Document2 pagesA Shew Recipe Costing XLSX 2api-242204869No ratings yet

- Grade 10 Lesson 3 Earthquake Seismic WaveDocument34 pagesGrade 10 Lesson 3 Earthquake Seismic Wavemae ann perochoNo ratings yet

- PN NCLEX Integrated A 1Document75 pagesPN NCLEX Integrated A 1jedisay1100% (1)

- Idioms With Hindi 1Document32 pagesIdioms With Hindi 1yqwe1093100% (1)

- Playbook Launchpackage Cassida Chain Oil XteDocument11 pagesPlaybook Launchpackage Cassida Chain Oil XteKiệt NgôNo ratings yet

- Hindu Code Bill Hindu Law Research PaperDocument4 pagesHindu Code Bill Hindu Law Research Paperputt jatt daNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 DLL Science 6 q3 Week 1Document5 pagesGrade 6 DLL Science 6 q3 Week 1MICHELE PEREZNo ratings yet

- Model No: ATBOX-G3-J4125: Product HighlightDocument2 pagesModel No: ATBOX-G3-J4125: Product HighlightTamNo ratings yet

- THW1.soft Drinks vCOMPLETEDocument2 pagesTHW1.soft Drinks vCOMPLETEjunho yoonNo ratings yet

- Write Up of Salt Analysis NH CL: Acidic Radical (Order Will BeDocument4 pagesWrite Up of Salt Analysis NH CL: Acidic Radical (Order Will BeRoshan AnsariNo ratings yet

- Amador D. Sandoval: Personal InformationDocument4 pagesAmador D. Sandoval: Personal InformationJohn Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- ΑΝΤΙΔΡΑΣΤΗΡΙΑ PDFDocument1 pageΑΝΤΙΔΡΑΣΤΗΡΙΑ PDFk_168911826No ratings yet

- Comparison ASTM A 3388 & ISO 11496Document1 pageComparison ASTM A 3388 & ISO 11496Rahul MoottolikandyNo ratings yet

- HMT SeminarDocument4 pagesHMT SeminarBhavesh JainNo ratings yet

- TissuesDocument49 pagesTissuessunnysinghkaswaNo ratings yet

- Sub-Compact Tractors: CT1021 CT1025Document16 pagesSub-Compact Tractors: CT1021 CT1025Abhinandan PadhaNo ratings yet

- Mental Health TheoriesDocument6 pagesMental Health TheoriesRodzel Oñate BañagaNo ratings yet

- Compiled 84 Halaman TropmedDocument78 pagesCompiled 84 Halaman TropmedDapot SianiparNo ratings yet

- The Development of AgricultureDocument6 pagesThe Development of AgricultureKaterin ZapataNo ratings yet

- MELCs SCIENCEDocument26 pagesMELCs SCIENCEArquero NosjayNo ratings yet

- Drug Dependency Examination (DDE)Document38 pagesDrug Dependency Examination (DDE)Ace VisualsNo ratings yet

- Password Based Circuit Breaker Control To Ensure Electric Line Mans Safety and Load Sharing IJERTCONV5IS13135Document4 pagesPassword Based Circuit Breaker Control To Ensure Electric Line Mans Safety and Load Sharing IJERTCONV5IS13135Pratiksha SankapalNo ratings yet

- Sexual Orientation: Gender, Transgender, and ConformanceDocument4 pagesSexual Orientation: Gender, Transgender, and ConformanceMaria GiannisiNo ratings yet