Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Is Vocabulary Just About Rote Learning?: Us To Communicate Is Something Which Is Highlighted by Nyāya-Vaiśe Ika School

Uploaded by

Dada RoxOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Is Vocabulary Just About Rote Learning?: Us To Communicate Is Something Which Is Highlighted by Nyāya-Vaiśe Ika School

Uploaded by

Dada RoxCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Is Vocabulary Just About Rote Learning?

In this essay we will explore the requirement of having large amount of

vocabulary in order to understand the world around us in better way. The world

around us is constituted with various real substances with some qualities. These

qualities are either inherent within these substances or perceived through

subjective experience of the object. When we make differentiation between

subjective experience of the object (svaprakāśatā) or self-aware nature of

knowledge and inherence of properties that are attached on to the material objects

(Timalsina 2008), we are taking into consideration the precise nature of

knowledge (jñāna) as something what Nyāya-vaiśeṣika thought of world to be.

According to them whatever that is knowable is namable (RW Perrett 1999). The

way they locate the importance of the words in understanding world is what

makes it easier for us, to recognize the significant importance given to the fact

that individual should have maximum vocabulary in order to be identified as

someone knowledgeable or in more general terms to be more intelligent in

modern world when we think of competitive examinations. These include

vocabulary to be important factor to judge his or her capacities to comprehend

well in particular language.

Just knowing the basic grammar or the way language is constructed is not

sufficient for individual to use language effectively and we need to know some

basic words that are used to construct a simple sentence. This is one way of

looking at the importance of vocabulary based upon a ‘usage of the language’.

But what is fundamental nature of words1 and how do they make it possible for

us to communicate is something which is highlighted by Nyāya-vaiśeṣika school

of Indian philosophy where they talk about padārtha. The word padārtha itself

mean that ‘the word that has some meaning’. (It appears quite funny when we try

think of importance of words through usage of words). When they speak about

padārtha it is the real objects and elements that they refer to in the world around

us. They divide world into particular categories. The metaphysical structure of

reality in this school makes it simpler to attribute meaning to the words and

achieve the relationship between words and these element of the world.

The primary category is said to be dravya (substance), where these substances are

supposed to pre-exist to have some properties attached to them and define its

actual nature. So it cannot be ‘I think therefore I am’ as Descartes famously says

1

Words have some meaning attached to it. Without any meaning words do not exist.

Abhijeet Kulkarni| Roll no. 163603001|TTIP|Date:20 Oct 2016|Assignment-4

2

it. According to realist perspective body pre-exist within which we think. So

existence of body is presupposed before the act of thinking. The peculiarity of

this specific category is that these substances are further divided into material and

non-material substances where subject of experience of object is also included to

be one of the substance which is non-material is ātman (soul) and manas (mind)

which is associated with a material body. So substance is something which

possesses guṇa (quality) and karma (motion or action) (King 1999). Substance is

something that cannot exist without these two categories which are indivisible

from substance. These three categories combine together to form a larger

category of satta (existent) as a declaration of something that is real.

When we think of words in parallel to the understanding of this metaphysical

structure of reality, then words are those symbols which hint at some relation to

the substance (dravya) which has some meaning which is related to the property

of the substance (guṇa) and are used with the help of some artificial rules

constructed in some definite framework to make some sense out of series of

words. This meaning which is constructed out of words is nothing but the essence

of the substance or bhāva of the substance. When we think of these categories in

relation with the words in the way which they are used, the importance given to

the vocabulary starts to unfold.

Dignāga proposed the doctrine of exclusion (apohavāda)2 to further rebuff

Nyāya-vaiśeṣika-s acceptance of the reality of universals (samānya) (King 1999).

Where he proposed principle of negation or exclusion. According to him

universals or class-names are constructed negatively which allows functioning in

broader network of signifiers (Arnold 2006). So words don’t build the direct

relationship to the substance but they develop relationship with everything else

than that specific substance. For example, when we call some substance as dog,

we develop the understanding which essentially imply that everything else than

this object is ‘not dog’. This leaves with no other option than to relate that

substance with word dog, which even imply that this substance is not horse, not

cow, not pencil, not human etc. When we take this precise usage of language as

exclusion it becomes evident to actually identify one substance different from

every other substance. To understand nature of substance completely with its

inherent qualities and essence there are two ways to actually locate that substance

different from everything else.

To understand this more clearly we will stick to the example dog where will talk

about one specific quality of dog that ‘dog barks’. To know that dog barks and

derive this conclusion to be true, there are two ways in which we can solve this

2

It is the theory of language and its usage.

Abhijeet Kulkarni| Roll no. 163603001|TTIP|Date:20 Oct 2016|Assignment-4

3

problem. First we will have to see and experience each and every dog that is

present on earth to propose that dog barks. By this we can claim that dog barks

unless and until we encounter with some dog which does not bark3. Practically to

claim this relation between dogs and act of barking by pratyakṣa pramāṇa (direct

perception) is impossible where pramā (object of knowledge) is ability of dog to

bark. So there is second way to deal with this practical difficulty is to experience

every dog barking (pratyakṣa pramāṇa) is to ‘infer’ (anumāna) that dog barks.

Here, the idea of exclusion with support of universals comes into play. To infer

that dog barks, we will have to know all other possibilities of substances and

relationships within those substances, to actually say that dogs do not mew as

cats’ mew, dogs do not growl because bears do it or even the fact that dogs do

not croak as frogs do it etc. The possibility to infer something strongly with some

level of certainty is based upon principle of exclusion. This is only possible when

we know what are the other possibilities; than the claim of stating something

obvious. In this same example to claim that something is dog, we will have to

know what are the other animals, to say it is not any of those animal. To state it

is an animal, we will have to know what are the all living things, that are not

animals. To state something is living, we will have to know, what are all non-

living things, that are not living and so on. So this list of substances can go on

towards infinity, unless and until all the substances in the world are not named

with particular word, to make a substantial claim that dogs are not humans.

From above examples and explanations, it is clear to realize why it is significantly

important to expand vocabulary and learn new words all the times. These words

are not only some random symbols to signify one quality or property of the

substance, but even signify the relationship between as many qualities as possible

to one particular substance or object. It is essential to understand meaning of the

word precisely to identify exact relation between word and its meaning to the

substance, because without such careful understanding of the word there is

possibility of stating something, which is not real or false due to possibility of the

same statement to be true in different context. For example, if one says dogs do

not talk when they bark, then there is problem with the statement and ambiguity

in the statement as to say dogs might be talking between themselves that humans

cannot comprehend or communicate back through mode of barking. But this does

not conclude that dogs cannot talk, because act of talking implies making some

sounds or actions to communicate with others who can understand those sounds

or actions4. It is as similar as if some French speaking person says that Japanese

3

We can even conclude that this specific dog is sick or there is some problem with his vocal chords. But here

we are talking specifically about non-barking dog who does not possess quality of barking.

4

Those(humans) who cannot speak use sign language which doesn’t not include any sound in communication

Abhijeet Kulkarni| Roll no. 163603001|TTIP|Date:20 Oct 2016|Assignment-4

4

speaking person cannot talk or communicate because he does not understand what

they are trying to say. But when we have precise understanding of words and

what does they exactly mean, when we use it in the particular context, it becomes

feasible to relate to the words outside us and interact with all those elements in

the world which has some meaning attached to it.

So according to Nyāya-vaiśeṣika when they structure the metaphysical categories

of reality, they imply that when something is knowable it can namable. Which

even imply having large sets of vocabulary enables us not only to understand

world clearly but perceive it differently. Remembering more numbers of words

is not only some mechanical act to test our capacity to rote learn something but

in a way it helps us to re-define world and increases the likelihood that we will

look into all possible relation between various elements (satta) into the world. It

might even help us to come out of stereotypes and miss-believes which were

imposed onto us by social hegemony while we grow up learning many things in

our childhood developing ways in which we interact with our surroundings then

it becomes important not only to re-relate existing knowledge but even learn

something new through learning just series of words with precise meaning and

ways in which those words can be used, to redefine humanity and human

understanding of the world. The more we cognize (jñāna5) about what is

happening around us and the world we are living into it becomes little easier to

locate ourselves and our existence within these structures of universe.

Consequently, it drives one to realize internal self and construct some

understanding about his or her identity. In today’s world where we have created

so many complexities while developing some understanding about it, it becomes

essential to step back and reconstruct these understandings by developing new

relations of transactions within world in all possible ways, by knowing more and

developing more knowledge to stabilize the misbalanced world.

5

The term, as used in Nyaya, is cognition that corresponds to the externals

Abhijeet Kulkarni| Roll no. 163603001|TTIP|Date:20 Oct 2016|Assignment-4

5

Bibliography

Timalsina, Sthaneshwar. Consciousness in Indian philosophy: The Advaita

doctrine of ‘Awareness only’. Routledge, 2008: 17.

Arnold, Dan. "On semantics and saṃketa: Thoughts on a neglected problem with

Buddhist apoha doctrine." Journal of Indian Philosophy 34, no. 5 (2006): 415-

478.

King, Richard. Indian philosophy: An introduction to Hindu and Buddhist

thought. Georgetown University Press, 1999.

Perrett, Roy W. "Is whatever exists knowable and nameable?" Philosophy East

and West (1999): 401-414.

Words: 1795

Abhijeet Kulkarni| Roll no. 163603001|TTIP|Date:20 Oct 2016|Assignment-4

You might also like

- Philo. of Language. LatestDocument26 pagesPhilo. of Language. LatestnorainiNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Research Methods in International RelationsDocument5 pagesWeek 5 Research Methods in International RelationsJeton DukagjiniNo ratings yet

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Rediscovered Books): Complete and UnabridgedFrom EverandTractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Rediscovered Books): Complete and UnabridgedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (15)

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (with linked TOC)From EverandTractatus Logico-Philosophicus (with linked TOC)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Karim - Advanced MetaphysicsDocument11 pagesKarim - Advanced Metaphysicsalican karimNo ratings yet

- The Notion of Meaning in SemanticsDocument4 pagesThe Notion of Meaning in SemanticsZoulfiqar AliNo ratings yet

- First GlossaryDocument4 pagesFirst GlossaryStella LiuNo ratings yet

- SemanticsDocument70 pagesSemanticsMohammedNo ratings yet

- Break Them All: A Modern Era Awakening!: Break Them All, #1From EverandBreak Them All: A Modern Era Awakening!: Break Them All, #1Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Semantics and Pragmatics NotesDocument13 pagesSemantics and Pragmatics NotesKELVIN EFFIOMNo ratings yet

- Semantics ch1 PDF 2Document36 pagesSemantics ch1 PDF 2nasser a100% (2)

- Semantics and Theories of Semantics PDFDocument15 pagesSemantics and Theories of Semantics PDFSriNo ratings yet

- Like Dreams & Clouds: Emptiness & Interdependence, Mahamudra & DzogchenFrom EverandLike Dreams & Clouds: Emptiness & Interdependence, Mahamudra & DzogchenNo ratings yet

- Semantics and Theories of SemanticsDocument15 pagesSemantics and Theories of SemanticsAnonymous R99uDjYNo ratings yet

- Body Language: Body Language And Non-Verbal Communication: How To Detect Lies And Communicate Without Saying A WordFrom EverandBody Language: Body Language And Non-Verbal Communication: How To Detect Lies And Communicate Without Saying A WordNo ratings yet

- Gleanings from Rig Veda - When Science Was ReligionFrom EverandGleanings from Rig Veda - When Science Was ReligionNo ratings yet

- The Activity of Speaking: Key Aspects and ImplicationsDocument9 pagesThe Activity of Speaking: Key Aspects and ImplicationsAchmad ToyyibulNo ratings yet

- A New Look at Language Thought and RealiDocument13 pagesA New Look at Language Thought and RealiMaycon Silva AguiarNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - Lesson 4 2022Document12 pagesModule 1 - Lesson 4 2022Rubie John BlancoNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philosophy My ReportDocument3 pagesContemporary Philosophy My ReportMylyn MylynNo ratings yet

- Philosophical ReflectionDocument5 pagesPhilosophical Reflectionjonas davidNo ratings yet

- Body Language: The Ultimate Self Help Guide on How To Analyze People And Learn Negotiation, Persuasion Skills For Dating And Influence People In BusinessFrom EverandBody Language: The Ultimate Self Help Guide on How To Analyze People And Learn Negotiation, Persuasion Skills For Dating And Influence People In BusinessRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- PragmaDocument4 pagesPragmaMade JulianiNo ratings yet

- The Nonverbal Factor: Exploring the Other Side of CommunicationFrom EverandThe Nonverbal Factor: Exploring the Other Side of CommunicationNo ratings yet

- Departure From Indifference: Probing the Framework of RealityFrom EverandDeparture From Indifference: Probing the Framework of RealityNo ratings yet

- On Language and Communication: Individual vs Community PerspectivesDocument17 pagesOn Language and Communication: Individual vs Community PerspectivesLaraNo ratings yet

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: The original 1922 edition with an introduction by Bertram RussellFrom EverandTractatus Logico-Philosophicus: The original 1922 edition with an introduction by Bertram RussellNo ratings yet

- Notes On Existence As A PredicateDocument7 pagesNotes On Existence As A PredicateJinti KalitaNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 Words and ThingsDocument6 pagesUnit 8 Words and ThingsPuthut FilthNo ratings yet

- Types of Pramana - 02 - NotesDocument5 pagesTypes of Pramana - 02 - NotesKrishna NimmakuriNo ratings yet

- The Five Dharma Types: Vedic Wisdom for Discovering Your Purpose and DestinyFrom EverandThe Five Dharma Types: Vedic Wisdom for Discovering Your Purpose and DestinyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- Screenshot 2024-01-09 at 2.28.36 PMDocument31 pagesScreenshot 2024-01-09 at 2.28.36 PMssg7fzf8mfNo ratings yet

- Space, Time, and Interpretation: How Habits Shape ExperienceDocument10 pagesSpace, Time, and Interpretation: How Habits Shape ExperienceAndrei Mikhail Zaiatz CrestaniNo ratings yet

- From Late 1970s - NonfictionDocument8 pagesFrom Late 1970s - NonfictionjustintoneyNo ratings yet

- Karma Agency and Freedom An Analytical Study of Agent Freedom in Classical Indian PhilosophyFrom EverandKarma Agency and Freedom An Analytical Study of Agent Freedom in Classical Indian PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- Sentences, Judgments, RealityDocument8 pagesSentences, Judgments, RealityThaddeusKozinskiNo ratings yet

- Ontologia Linguagem e Teoria LinguisticaDocument10 pagesOntologia Linguagem e Teoria LinguisticaAna CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Nirukta of YaskaDocument3 pagesNirukta of YaskaVladimir YatsenkoNo ratings yet

- Consciousness - Identity and SelfDocument3 pagesConsciousness - Identity and SelfDada RoxNo ratings yet

- DvijaDocument3 pagesDvijaDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Parenting and Cyber World.Document6 pagesParenting and Cyber World.Dada RoxNo ratings yet

- Is Nature Really ImportantDocument3 pagesIs Nature Really ImportantDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Padārtha: Bhāva (Essence of Existence) and Abhāva (Renders Negative Statements True)Document3 pagesPadārtha: Bhāva (Essence of Existence) and Abhāva (Renders Negative Statements True)Dada RoxNo ratings yet

- Padārtha: Bhāva (Essence of Existence) and Abhāva (Renders Negative Statements True)Document3 pagesPadārtha: Bhāva (Essence of Existence) and Abhāva (Renders Negative Statements True)Dada RoxNo ratings yet

- Be Critical To Understand MoreDocument2 pagesBe Critical To Understand MoreDada RoxNo ratings yet

- E SocietyDocument6 pagesE SocietyDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Political Significance To Indian Philosophy1Document3 pagesPolitical Significance To Indian Philosophy1Dada RoxNo ratings yet

- Abhijeet Kulkarni Textual Traditions of Indian PhilosophyDocument10 pagesAbhijeet Kulkarni Textual Traditions of Indian PhilosophyDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Abhijeet Kulkarni Textual Traditions of Indian PhilosophyDocument10 pagesAbhijeet Kulkarni Textual Traditions of Indian PhilosophyDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Abhijeet Kulkarni Time and NarrativeDocument9 pagesAbhijeet Kulkarni Time and NarrativeDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Abhijeet Kulkarni Collective Social PDFDocument10 pagesAbhijeet Kulkarni Collective Social PDFDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Abhijeet Kulkarni Time and NarrativeDocument9 pagesAbhijeet Kulkarni Time and NarrativeDada RoxNo ratings yet

- Fitness RX For Women - December 2013Document124 pagesFitness RX For Women - December 2013renrmrm100% (2)

- ZTE UMTS KPI Optimization Analysis Guide V1 1 1Document62 pagesZTE UMTS KPI Optimization Analysis Guide V1 1 1GetitoutLetitgo100% (1)

- SE 276B Syllabus Winter 2018Document2 pagesSE 276B Syllabus Winter 2018Manu VegaNo ratings yet

- Autocad Lab ManualDocument84 pagesAutocad Lab ManualRaghu RamNo ratings yet

- DesignDocument2 pagesDesignAmr AbdalhNo ratings yet

- Bipolar I Disorder Case ExampleDocument6 pagesBipolar I Disorder Case ExampleGrape JuiceNo ratings yet

- of The Blessedness of God.Document3 pagesof The Blessedness of God.itisme_angelaNo ratings yet

- Char Lynn 104 2000 Series Motor Data SheetDocument28 pagesChar Lynn 104 2000 Series Motor Data Sheetsyahril boonieNo ratings yet

- Zooniverse Book 2022Document28 pagesZooniverse Book 2022Dr Pankaj DhussaNo ratings yet

- Newton's Laws of Motion Summative TestDocument1 pageNewton's Laws of Motion Summative TestXHiri Pabuaya MendozaNo ratings yet

- 05.G. Before Takeoff CheckDocument4 pages05.G. Before Takeoff CheckUDAYAPRAKASH RANGASAMYNo ratings yet

- Waste Management in Vienna. MA 48Document12 pagesWaste Management in Vienna. MA 484rtttt4ttt44No ratings yet

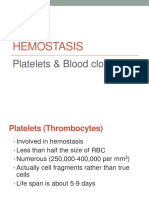

- Platelets & Blood Clotting: The Hemostasis ProcessDocument34 pagesPlatelets & Blood Clotting: The Hemostasis ProcesssamayaNo ratings yet

- Slovakia C1 TestDocument7 pagesSlovakia C1 TestĐăng LêNo ratings yet

- Miniaturized 90 Degree Hybrid Coupler Using High Dielectric Substrate For QPSK Modulator PDFDocument4 pagesMiniaturized 90 Degree Hybrid Coupler Using High Dielectric Substrate For QPSK Modulator PDFDenis CarlosNo ratings yet

- Tutorial - DGA AnalysisDocument17 pagesTutorial - DGA Analysisw automationNo ratings yet

- Understanding Revit Architecture - BeginnersDocument56 pagesUnderstanding Revit Architecture - BeginnersBudega100% (95)

- Problem Set 3_Cross-Text ConnectionDocument31 pagesProblem Set 3_Cross-Text Connectiontrinhdat11012010No ratings yet

- Jean NouvelDocument1 pageJean Nouvelc.sioson.540553No ratings yet

- Rate Analysis-Norms 1Document10 pagesRate Analysis-Norms 1yamanta_rajNo ratings yet

- SilverDocument16 pagesSilversharma_shruti0% (1)

- Estimation of Fabric Opacity by ScannerDocument7 pagesEstimation of Fabric Opacity by ScannerJatiKrismanadiNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Chem 1Document25 pagesModule 2 Chem 1melissa cabreraNo ratings yet

- Lmx2370/Lmx2371/Lmx2372 Pllatinum Dual Frequency Synthesizer For RF Personal CommunicationsDocument16 pagesLmx2370/Lmx2371/Lmx2372 Pllatinum Dual Frequency Synthesizer For RF Personal Communications40818248No ratings yet

- Bartle Introduction To Real Analysis SolutionsDocument7 pagesBartle Introduction To Real Analysis SolutionsSam Sam65% (20)

- Digital control engineering lecture on z-transform and samplingDocument13 pagesDigital control engineering lecture on z-transform and samplingjin kazamaNo ratings yet

- Guía de Instalación y Programación: Sistema de Seguridad de 32 ZonasDocument68 pagesGuía de Instalación y Programación: Sistema de Seguridad de 32 ZonasfernanfivNo ratings yet

- Analog Layout Design (Industrial Training)Document10 pagesAnalog Layout Design (Industrial Training)Shivaksh SharmaNo ratings yet

- Imsa Catalog Imsa CatDocument16 pagesImsa Catalog Imsa CatDaniel TelloNo ratings yet

- DST Sketch S.E Alhamd 2Document3 pagesDST Sketch S.E Alhamd 2GPCNo ratings yet