Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teaching Science in English Through Cognitive Strategies: Institución Universitaria Colombo Americana-ÚNICA, Colombia

Uploaded by

Syakti PerdanaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Teaching Science in English Through Cognitive Strategies: Institución Universitaria Colombo Americana-ÚNICA, Colombia

Uploaded by

Syakti PerdanaCopyright:

Available Formats

Gist Education and Learning Research Journal. ISSN 1692-5777.

No. 6, november 2012. pp. 129-146

Teaching Science in English

through Cognitive Strategies1

Yuly Andrea Bueno Hernández2*

Institución Universitaria Colombo Americana-ÚNICA,

Colombia

Abstract

This study shows the impact and results of implementing three cognitive

strategies in science teaching in English. The three-month study was carried

out with 144 second grade students at a public school of Bogota’s Bilingualism

program, but only 40 students contributed in the data collection process. Data

collected from observations and fieldnotes, surveys, interviews, videotapes, and

photographs revealed that the use of the strategies helped children understand

not only the content and language, but also the class tasks. Preliminary findings

showed that students are the main actors of their learning, and they gain certain

autonomy and independence using the cognitive strategies. On the teachers’

side, strategies facilitated classroom management and engagement. The author

recommends the constant and gradual implementation of learning strategies not

only in science classes, but also in the rest of the content classes to integrate

language and content easily.

Keywords: cognitive strategies, science teaching, sheltered instruction,

students’ learning and emotions.

Resumen

El presente artículo muestra el impacto y los resultados de la implementación

de tres estrategias cognitivas en la enseñanza de ciencias naturales en inglés. El

estudio, que tuvo una duración de tres meses, se llevó a cabo con 144 estudiantes

de segundo grado de un colegio público, que hace parte del programa de

bilingüismo de Bogotá, pero solo 40 estudiantes contribuyeron en el proceso

de recolección de información. Los datos recogidos a partir de observaciones

y notas de campo, encuestas, entrevistas, videos y fotografías revelaron que el

uso de las estrategias ayudó a los niños a comprender no sólo el contenido y

el lenguaje, sino también las actividades de clase. Los resultados preliminares

mostraron que los estudiantes son los actores principales de su aprendizaje

129

y adquieren cierta autonomía e independencia utilizando las estrategias

cognitivas. Por el lado del docente, las estrategias facilitaron la gestión del

1

Received: February 23rd, 2012 / Accepted: May 14th, 2012

2

Email: sopia_170@hotmail.com

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

aula y el compromiso con la misma. El autor recomienda la implementación

constante y gradual de las estrategias de aprendizaje no solo en las clases de

ciencias naturales, sino también en el resto de las materias de contenido para

integrar el lenguaje y el contenido fácilmente.

Palabras claves: estrategias cognitivas, enseñanza de ciencias naturales,

instrucción dirigida, aprendizaje y emociones de los estudiantes.

Resumo

O presente artigo mostra o impacto e os resultados da implantação de três

estratégias cognitivas no ensino de ciências naturais em inglês. O estudo,

que teve uma duração de três meses, foi realizado com 144 estudantes de

segunda série de um colégio público, que faz parte do programa de bilinguismo

de Bogotá, mas só 40 estudantes contribuíram no processo de recolha de

informação. Os dados recolhidos a partir de observações e notas de campo,

pesquisas de opiniões, entrevistas, vídeos e fotografias revelaram que o uso das

estratégias ajudou as crianças a compreender não só o conteúdo e a linguagem,

senão também as atividades de classe. Os resultados preliminares mostraram

que os estudantes são os atores principais da sua aprendizagem e adquirem

certa autonomia e independência utilizando as estratégias cognitivas. Pelo lado

do docente, as estratégias facilitaram a gestão da aula e o compromisso com a

mesma. O autor recomenda a implantação constante e gradual das estratégias

de aprendizagem não só nas aulas de ciências naturais, senão também no resto

das matérias de conteúdo para integrar a linguagem e o conteúdo facilmente.

Palavras chaves: estratégias cognitivas, ensino de ciências naturais,

instrução dirigida, aprendizagem e emoções dos estudantes.

Introduction

B

ased on my experience, I consider that teaching English is not

the same as teaching science in English. The difference lies

130 mainly on the fact that content instruction in English implies

specific teaching methodologies as well as strategies to help students

learn the language while learning the content. If teaching English is

by itself a complicated matter, teaching science in English to Spanish

speakers is exponentially more challenging.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

Language is central to teaching and learning every subject.

Teachers use language to help students learn contents, and students use

language to explore content and to express what they have learned. So,

science students who are simultaneously learning English need to have

a good command of the language to master the content. However, when

they struggle with the language, they fall behind with the content, too.

Thus, teaching science in English through the use of the Sheltered

Instruction principles is necessary to help students learn content

concepts and develop their language skills simultaneously. However,

this is not enough, which brings into life the use of strategies to make

learning meaningful and to achieve the goal of bilingualism. In my

experience as a student-teacher in a public school, I taught science to

second grade students following not only the curriculum of the school,

but also the Sheltered Instruction and cognitive strategies. Therefore,

the aim of this study is to describe the effects and implications of using

three cognitive strategies (Classify, Acting out, and Imagery) with

second-grade students at a public school of Bogota’s Bilingualism

program, particularly regarding their English and science learning, and

emotions.

This action research study took place at a pilot public school

of Bogota’s bilingualism program from March to May, 2011. It is a

coed school, which is starting to implement the National Ministry

of Education bilingual project. This project has been advised by the

Universidad Nacional through the linguistics department. The target

population of the study includes four second grade courses, whose

number of students range from 35 to 37. However, not all of them

participated in the data collection process; 10 students (5 girls, and 5

boys) were chosen from each course (giving us a total of 40 students) to

provide their ideas, experiences, and feelings regarding the class. The

students’ selection process was at random to avoid bias. The students’

ages range from 6 to 8 years old. Data from the study were collected

through daily observations and fieldnotes, surveys to the 40 students,

interviews with two teachers, weekly videotapes, and photographs.

Theoretical Framework 131

Integrating language instruction with subject matter instruction

is still a challenge for educators, especially if they lack training and

knowledge. Content-based instruction has been carried out in many

grade levels and educational programs. However, how do we know if

the focus of this trend, content in language instruction, is effectively

applied or not? Not many primary teachers in Colombia know or use the

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

Sheltered Instruction approach in content-based instruction, which has

been used to help students with a limited English proficiency to learn

English through content areas simultaneously. It has been proved in the

United States that this instructional approach works and is effective in

primary levels, but little research has been done in Colombia in this

regard. It is therefore important to find out if this method helps teachers

develop optimal ways to present content and at the same time keep it

understandable to second-grade students, who are beginning to learn

the language of instruction (English) and the content (Science). For this

reason, this study attempts to point out how the implementation of the

Sheltered Instruction approach along with the use of strategies of the

cognitive level in science classes makes learning and teaching different.

To have a deeper understanding of this study, a short explanation of

what Sheltered Instruction and learning strategies are will be given.

Sheltered Instruction

It is defined as “an approach for teaching content to English

learners (ELs) in strategic ways that make the subject matter concepts

comprehensible while promoting the student’s English language

development” (Echevarria, et al 2004, p. 2). Such instruction came

out as the result of developing strategies to foster second language

development and academic learning through the use of the second

language (Peregoy & Boyle, 2003, p. 78). Sheltered instruction or

SDAIE (Specially Designed Academic Instruction in English) provides

access to the core curriculum, English language development, and

opportunities for social interaction. Basically, this model is a resource

teachers can count on to improve their teaching and help learners to

grasp content and language simultaneously. Its primary goal is to show

teachers the way to teach content effectively to English learners while

developing their language proficiency.

Learning Strategies

This refers to the mental processes that enhance comprehension,

132 learning, and retention of information (Echevarria, et al 2004, p.

81), which in other words are the special thoughts or behaviors that

exhibit these outputs (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990, p. 1). Furthermore,

“Researchers have learned that information is retained and connected

in the brain through mental pathways that are linked to an individual’s

existing schema” (Echevarria, et al 2004, p. 81). This suggests that

the initiation and use of learning strategies activates mental processes

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

through the associations between new and old learning. In the same

way, the explicit teaching of learning strategies that facilitate the

learning process involves teaching students to access information in

memory, helping students make connections between what they know

and what they are learning, assisting students in problem solving, and

promoting retention of newly learned information.

Three types of learning strategies have been identified (O’Malley

& Chamot, 1990). They are: metacognitive strategies, cognitive

strategies and social/affective strategies. For this study, only the

cognitive strategies will be considered, which according to Echevarria

“help students organize the information they are expected to learn

through the process of self-regulated learning” (as cited in Paris,

2001). Besides this, the ultimate goal of using these strategies is to

foster independence in students and have student-centered classes for

teachers. As it is very difficult for beginner students to initiate an active

role in the use of the strategies, Sheltered Instruction teachers should

scaffold their use and should help learners to focus their mental energy

on their thinking development skills.

From the cognitive level strategies, only three strategies are the

target of the study: classifying or grouping, imagery and acting out. The

first strategy, classifying or grouping, is focused on relating or putting

words within categories according to their attributes, and the mental

process that is expected from students is to remember information. The

second strategy, imagery, is related to the creation of images to represent

information, and it requires that students visualize knowledge, create a

mental picture and draw it. It is also called imaging and it encourages

students to create an image in their minds to support the understanding

of concepts or problems to be solved (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990).

Finally, the last strategy, acting out, is about creating different gestures

and movements with the body to visually represent ideas, concepts,

and vocabulary. It involves creativity and the ability to remember and

connect information. The good point of this strategy is precisely the

opportunity that students have to create experiences with which to link

the new vocabulary.

133

Review of Related Literature

Teaching content in English is by far more demanding than

teaching English only. “Teachers of English language learners (ELLs)

face several challenges, not the least of which is facilitating students’

simultaneous acquisition of academic content and English language and

literacy” (Hart, & Lee, 2003, p. 476). Thanks to the Sheltered Instruction

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

approach not only can teachers face this challenge in strategic ways, but

also students get better preparation in terms of language and content

(Diaz, 2010). However, there is little evidence of this in Colombia,

except for the research studies pioneered by UNICA University, which

is one of the reasons why this study is going to be carried out. The main

issue with content-based instruction is that ELL students do not have

enough support from the teacher to handle content concepts in a yet-

unmastered language (Lee, 2005). Furthermore, in some cases, teachers

lack preparation on how to provide linguistic and content support to

students so that they can learn both things simultaneously and develop

skills. Science is one of those subjects that students learn through rote

learning because they do not find sense in what they are learning, and

they just need to pass a test. Thus, incorporating cognitive strategies

to teach content-based instruction may facilitate students’ learning and

change the traditional way science has been taught.

Motivation

When teaching science or any other subject in a foreign

language, in this case English, with the use of strategies, it is not only

important to consider that students will have to deal with language,

content and strategies, but teachers should think of how to integrate

those components and foster motivation. This aspect affects how hard

students are willing to work on a task, how much they will persevere

when they are challenged, and how much satisfaction they feel when

they accomplish a learning task (Chamot, et al, 1999). Several studies

have found connections between motivation for language learning and

strategy use. In a large-scale study of US college students, Oxford and

Nyikos (1989) found that more motivated learners used four out of

five categories of strategies more frequently than did less motivated

students. Also, Okada, Oxford, and Abo (1996) conducted a study with

36 learners of Japanese and 36 learners of Spanish and they found that

there was a very strong relationship between the use of metacognitive,

cognitive and social strategies and several motivational aspects in

both language groups. Students tended to be more engaged in their

classes, they participated more and they felt eager to continue learning.

134 However, all these studies converge in the same concern, causality:

whether motivation fosters strategy use or, conversely, strategy use leads

to better language performance, which in turn increases motivation and

thus leads to increased strategy use (Okada et al. 1996).

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

Proficiency and Achievement

Each time a teacher implements something new in his or her class,

the ultimate goal is always to achieve a positive change in learning,

teaching and even in students’ performance. This is one of the major

reasons to research strategy use in language learning: to determine the

relationship between strategies and proficiency. In a study carried out

with 78 Japanese college English majors, Takeuchi (1993) reported

that some 60 per cent of the variance in the Comprehensive English

Language Test (CELT) scores was associated with strategy use on the

SILL. In the same way, a study by Park (1997) conducted with 332

Korean University Students found a close linear relationship between

SILL strategies and English proficiency measured by a practice version

of the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL). These studies

suggest that there is a direct relation between strategy use and the

achievement and improvement in second language proficiency.

Content-based Learning Strategies Instruction

A number of studies on the Cognitive Academic Language

Learning Approach (CALLA) related to learning strategies instruction in

content-based ESL have been investigated, and they reported successful

use of strategies by students. One example of this is the study carried out

by Chamot, Dale, O’Malley, & Spanos (1993) where teachers in ESL-

mathematics classrooms implemented learning strategies instructions

to assist students in solving word problems. Mainly, the study consisted

of teaching students how to use the following strategies: planning,

monitoring, problem-solving, and evaluating in a sequential order to

solve word problems. It was found that students who had been provided

with explicit and frequent strategies instruction (high-implementation)

performed better on a word problem think-aloud interview than students

in low-implementation classrooms. In the same way, another study

in the science area carried out by Varela (1997) shows the effects of

CALLA learning strategies instruction in a middle-school ESL-science

classroom compared with a similar classroom that received equivalent

instruction without the learning strategies. Students in the intervention

classroom were taught how to use strategies in their oral report on 135

the science fair projects. It was found that students in the strategies

group reported using significantly more strategies than the control

group students did. Also, their performances showed considerable

improvement over the performances prior to the strategies instruction.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

Research Design

Context

This action research study was carried out in a pilot public school

of Bogota’s bilingualism program from March to May, 2011. It is a

coed school, which is starting to implement the National Ministry of

Education bilingual project and this project has been advised by the

Universidad Nacional through the linguistics department. The aim

of the project is to get students acquainted with science concepts in

English and the dynamics of learning a subject matter in a foreign

language. However, not all the school teachers are trained in both

aspects, language and content, but they are getting prepared. So, this

gave way to my intervention as science teacher in the school. Regarding

the time intensity, students take 4 hours of science class in English

and 5 hours of English class a week. This time is not only devoted to

learning the language and the subject content matter concepts, but also

to train students on basic commands and expressions to communicate

in English.

Participants

The participants in this study were students and teachers of second

grade at a public school in Bogota. The total of students who participated

in the study was 114, but only 10 students (5 girls, and 5 boys) from

four second grade courses, whose number of students range from 35 to

37, participated in the surveys. These 40 students’ selection process was

at random to avoid bias. They provided their ideas, experiences, and

feelings regarding the class. The students were little children, whose

ages range from 6 to 8 years old, of a low to middle-low economic

status, and their native language is Spanish. Regarding teachers, an

adult science teacher and a pedagogical assistant from Universidad

Nacional contributed in the interviews. They were sometimes passive

observers in the science classes.

Data Collection Instruments

136

In this study, qualitative data collection techniques were used as

the primary research method.

Direct Active Participant Observations. This technique was

useful to observe the outcomes of using cognitive strategies in terms of

learning and emotions. Also, this allowed me to monitor the effects of

my teaching and adjust instruction accordingly.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

Fieldnotes. Daily notes from the observations were taken. They

were divided in two parts: one-month field notes, and two-month field

notes. In the one-month field notes, I focused my attention on the

problem and class structure without the use of the strategies as well

as my implicit implementation of the three cognitive strategies. In the

two-month field notes, the target was to capture the effects of using

cognitive strategies and the impact of their explicit teaching.

Surveys. One survey was applied to 40 second grade students

(20 girls and 20 boys) to gather information about their feelings,

experiences, and thoughts in regards to the use of the three cognitive

strategies (Classifying, Acting out, and Imagery) in the science class.

These surveys were applied by the end of May after students were

familiarized with the use of strategies and had received explicit

instruction about their use. The questions had options to facilitate the

analysis.

Semi-structured interviews. After a three-month intervention in

science class as observers, two teachers were interviewed to know their

opinions about the impact of using the three cognitive strategies. The

homeroom teacher that was interviewed accompanied me every class

during the last two months and the other teacher was the pedagogical

assistant of the Universidad Nacional.

Videotapes. One class a week was videorecorded during two

months. The focus was the use of the three strategies, the instruction of

tasks, their accomplishment, the students’ intervention in the class, and

the outcome and input of the strategies.

Photographs. This tool was useful to capture the work done by

children after using a strategy. It evidences their learning and it is a

physical way to demonstrate the mental processes expected when using

strategies.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

After analyzing the data collected from the different sources, the

following themes came up. It is important to mention that the following

data results are not only due to the implementation of the strategies, but 137

also the use of some Sheltered Instruction principles.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

Simultaneous English and Science Learning

According to the results from the surveys, all the population

surveyed agreed on having learned science and English simultaneously

during my intervention as science teacher. However, their reasons

varied as shown in Figure 1. It is shown that only 10.2% of

Figure 1. Why have you learned science and English simultaneosly?

the students think that their science and English learning is due to

the use of the three cognitive strategies and their usefulness. The rest of

the students share the opinion that the activities, the teacher instruction,

and their own interest are what have determined their dual learning.

However, my intervention as a teacher and the activities developed

in class were focused merely on the strategies and the principles of

Sheltered Instruction, which reveals that these students indirectly are

recognizing their learning thanks to the strategies. One reason for not

mentioning the strategies in their answers may be that as students are

second graders, they are not conscious of their learning process and

they cannot reflect upon it yet, even though the strategies were made

explicit during the classes. Children perceived the strategies as a tool,

but not as the cause of their learning due to their lack of awareness.

In this regard, in the interviews teachers revealed that indeed students

are learning both things (language and content) simultaneously due to

the use of strategies and the process the teacher has had with them.

However, they also consider that their English learning at this level

138 is focused on vocabulary, the pronunciation of key science concepts,

some simple grammatical structures, and basic English commands.

They made emphasis on the fact that learning English and science

simultaneously is a process, which takes time and needs to be constant

to achieve results in the future.

In addition, the surveys showed that 89% of the representative

population of second grade considers that they feel happy learning

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

science and English simultaneously; none of the students expressed

that they felt bored or sad. In the same way, in the interviews teachers

confirmed this information by saying that children felt fine, relaxed, and

happy to learn; they considered learning to be a game and they liked to

learn.

Based on my fieldnotes, at the beginning, I perceived that English

in the science class was considered to be a barrier for children to learn

because they demonstrated that they had learned the content, but they

were not able to express things because of the language. Then, I realized

that they were lacking training and familiarity with the language, not

to say that they are in a silent period. In the first classes during the

first month of observation, I talked in English 100% of the class, and

children were unresponsive, but attentive. It was probably the first time

somebody gave them a class in English. They all looked at me with a

lost gesture on their faces, but the body movements and the drawings

helped them to create an idea of what I was saying, which was not

always the right one. The homeroom teacher told me to speak in Spanish

and to use English merely for the key science words, but that translating

them would be a lot easier for children. Thus, I realized that their “dual”

learning was aimed at learning a list of isolated English vocabulary.

During the next two-month observation period, when I started

to implement some Sheltered Instruction ideas (lesson-planning,

scaffolding processes, clear instruction, adaptation of content, setting

objectives, using visual aids) along with the three cognitive strategies

(classifying, imagery, and acting out), changes in their dual learning

(content and language) were noticed. Children started to associate and

retain English words in context; they knew what they meant without

having to translate them, they learned their pronunciation through

games and songs, and they were able to complete simple written

prompts related to the vocabulary studied. In the same way, vocabulary

was recycled in each lesson, and students got used to listening to me

in English. They were able to understand when I spoke in English,

although I obviously had to change the speed of the speech. I used

English 90% of the class, and the remaining 10% was in Spanish to

give instructions, clarify information related to content, or get students’

attention. 139

Students’ Learning Process

100% of the students agreed on saying that the use of the strategies

has helped them learn, but their reasons differed a bit. 15 out of 40

students, which correspond to 37.5 % of the students, think that the

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

strategies have helped them learn because they are interesting and easy

to apply, while 17.5% attribute this to the fact that the strategies have

helped them either retain information easily or do things they like, such

as drawing or acting. This suggests that disregarding the reason they

attribute to their learning, students recognized the strategies as a factor

for their learning (when formally asked) although they are not totally

aware of them, which does not mean that they do not know how to use

the strategies. In this aspect, teachers manifested that even though 36 or

37 students are not easy to manage, they agreed on the fact that about

75% or 80% of the students are learning, and they demonstrated this

through the way they use vocabulary, structures and content within the

classroom when developing their tasks.

Students were asked about the changes they perceived with

the strategies and the results show that the answers are homogenous

in the four courses and that 47% of the students consider the “better

grades” factor as the main way in which the strategies benefited them.

It is just 25% of the students who think that enjoyment in class, better

understanding, and better grades altogether are the changes they have

undergone with the use of the strategies. This information is confirmed

in the interviews, where teachers expressed that the impact the strategies

have had on the students’ learning process is positive and meaningful

since they are doing things (drawing, acting out, and classifying) that

they like and enjoy and which creates stronger connections in their

minds. The pedagogical assistant of Universidad Nacional stated that

“the impact of those strategies on the children is basically lifetime

learning.” Thus, they suggested that those cognitive strategies not only

were useful for learning during that period, but they will facilitate their

future learning if the strategies are used.

Similarly, the information gathered from the videotapes and

fieldnotes is evidence of the fact that children learned thanks to the

strategies, and also they showed the impact the strategies had on

students’ learning in terms of autonomy, creativity, understanding, and

involvement. During the first-month observation period, it was observed

that students were not thinking, they were filled out with nonsensical

information; their role was limited to copying information from the

140 board, but little attention was paid to their thinking processes. Children

were not able to associate information, apply knowledge, and not even

transfer ideas to other contexts. With the use of the strategies, children

started to wake up their minds; their learning process was strengthened

by providing them with the tools and not the products.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

Another benefit and change of implementing those cognitive

strategies in terms of the students’ learning process is that they

understood concepts easily because definitions at this age do not say

much to children, but doing something tangible and real allowed

them to grasp concepts and to retain them for a longer time period.

The strategies facilitated the students’ understanding and they helped

children clarify ideas. Also, when using the strategies children tended

to be more focused on their task, and their levels of concentration

increased. As the activities required students to do something and

sometimes to interact, children had to strain their minds to think and

connect ideas, which guarantees learning for life and not merely for a

class.

Furthermore, these cognitive strategies were also useful to recall

information (concepts and vocabulary) and to have students respond

for their own learning; they gained certain autonomy and independence

in their work. In fact, when applying the strategies, children had to

remember the main aspects of the input, and they had to associate that

information with their previous knowledge in order to be able to do their

task using the strategy. However, when children had not understood

the concepts, they happened to understand them through the use of the

strategies. Also, in the photographs, the students’ efficient use of the

strategies shows progress through the science tasks’ accomplishment

and the quality of the students’ work as the time goes by.

Motivation and Students’ Emotions

Based on the analysis from the survey results, it was found

that 87% of the second grade students felt happy using the cognitive

strategies (acting out, classifying, and imagery), and none expressed

feeling bored or sad using them. Similar results were revealed by

the teachers in the interviews, where they affirmed that children felt

different in the science class since the strategies resulted in something

innovative for children. They are separated from paper-pencil activities,

and different things were combined (drawing, acting, classifying,

matching, giving names to categories, etc) which made them feel

comfortable and relaxed enough to learn in the class. Also, the teachers 141

agreed on saying that children felt more motivated and happy in the

science class compared to the rest of the classes, in which they merely

wrote. This shows that the use of these cognitive strategies (classifying,

acting out, and imagery) created the desire to learn in the science class.

Besides this, when students were asked in the survey whether or

not they liked the science class, 100% of them said that they did like

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

the class. Then, they were asked for their reasons and 19 out of 40

students which correspond to the majority reported that they liked the

science class because both the topics and the class were fun. 17 out of

40 students said that they liked the class because they learned a lot, so

once again they were not explicitly acknowledging that the strategies

were the cause of their like for the class, but indirectly they agreed on

this because if they learned a lot and the class was fun, it was due to the

implementation of the strategies and the teacher intervention.

In the fieldnotes, I also noticed that children enjoyed using

the strategies and different from having to write merely, they kept

their minds busy with something that required them to think, which

encouraged them to work and learn. It can be said that when children

used the strategies in the science class, their level of motivation

increased and it was demonstrated through the children’s enthusiasm to

participate and work in class.

Class Dynamics Changes

According to the fieldnotes and videotapes of the first-month

period, it can be said that the class was a bit harder to manage and

instruction was the focus. Science classes were teacher-centered and

there was some, if only a little, student involvement. As the groups were

difficult to manage in terms of discipline, teachers assigned worksheets

where children had to color and paste, but content and language were

left aside. The classes tended to be very disorganized and noisy, and

children got distracted because they did not know what they had to do.

Afterwards, when the strategies started to be implemented and children

started to be trained in their use, children were a bit more attentive to

the input, but anyway they tended to get distracted because they did

not understand instructions and as it was the first time they had to do

something different from writing, they felt insecure. Fortunately, with

time, students got adapted to the use of the three cognitive strategies

(acting out, classifying, and imagery) and the results were dramatic

not only in terms of learning, but also in the class structure and in the

teacher’s role.

142 There was a noticeable change in classroom management with

the strategies; when using the strategies, children were so concentrated

and focused that they did not disturb each other and the times they

stood up and walked around the room decreased. There was little

noise in the room and I could speak without having to scream. When

using the acting out strategy, children tended to get so excited that they

shouted and it was difficult for me to control them, but as they wanted

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

to continue using the strategy, I could control them with it. Children

were more concentrated when using the strategies and even though they

interacted more with each other, they did not get disorganized, and their

behavior changed for the better. In the same way, I could perceive that

the classroom climate changed with the implementation of strategies

because the class could be delivered, students respected each other, and

they were not nervous about making mistakes.

In addition, the strategies benefitted my instruction as a teacher in

the sense that with the use of the strategies I could create more dynamic

and challenging activities, where children had to think and do mental

processes necessary to accomplish tasks. The strategies were useful to

avoid lectures as one interviewed teacher said, and also they allowed me

to create tasks from which children could benefit in terms of learning

and enjoyment. Also, with the strategies, students knew what to expect

from the class, and they knew what they had to do.

In the same way, the strategies facilitated the teacher role since

students already knew how to apply the strategies to the different topics

and activities. “Students got used to the application of strategies and

they were already familiar with them, so that the teacher did not even

have to explain what they had to do” (Extracted from fieldnotes April

25th, 2011). Thus, the strategies allowed the teacher to separate from

formal instruction, give the opportunity to children to develop thinking

skills, and have a focused-output class.

Besides this, strategies were reported to be useful for both

teachers-students’ assessment and self-assessment. When students

used the strategies effectively, that is to say with the set purpose and

to accomplish the assigned activity, the teacher could notice if students

understood the topic and if further practice or teacher instruction was

necessary. The strategies allowed the teacher to perceive the learning

process of students, if they were learning or if they were merely doing

a task. As in all classes the topic of the last class was reviewed and

articulated with the new topic, and it was noticed if children made

connections with past learning and new knowledge using the strategies.

In the same way, through the use of strategies, children could, to a

certain degree, monitor their learning in the sense that they were aware

of their mistakes and they could check their understanding of the topic. 143

However, as they are children and they are just starting their learning

process, they noticed their mistakes with the teacher’s assistance, and

not by themselves.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies B

Findings

This study revealed that the use of the three cognitive strategies

(classifying, imagery, and acting out) integrates the students’ dual

learning (science and English) and makes the language and content

concepts easier to grasp for students and to teach for teachers. In the

same way, some of the benefits found with the use of the strategies were:

they allowed children to build vocabulary, support their understanding,

organize information mentally, and provide language support. Not only

did the strategies have an impact in students’ learning process, but also

in their learning skills. Besides this, the efficient use of the strategies

facilitated the task accomplishment and they guarantee learning through

thinking; students had better mental processes.

Even though second graders are starting to get acquainted with

simultaneous English and science learning, they were able to associate

information, apply knowledge, recall ideas, and sometimes transfer

ideas to other contexts thanks to the use of the strategies. Also, the

students’ level of understanding, engagement, autonomy, creativity

and concentration increased when using the three cognitive strategies

(classifying, imagery, and acting out). By teaching children how to use

the cognitive strategies, they got more efficient in task accomplishment

and they were independent users of the strategies.

Another important finding was that the use of the strategies in

the science class created the desire to learn in students, they were

more motivated and enthusiastic to work, and they, in turn, became

more active learners. However, the strategies had a strong impact not

only in students, but also in the classroom dynamics. The effective

use of cognitive strategies in large-size groups worked as a classroom

management technique and changed students’ behavior for good, but

teachers should not expect to achieve a quiet environment, but a place

where students interact and the level of discipline problems decreases.

To use strategies as part of the teaching methodology is useful to

avoid lectures, and have a more student-centered class, where different

types of activities can be created. So, the strategies implementation

keeps students focused on their task and they give way to well-structured

144 focused-output classes with clear expectations for both students and

teachers.

Conclusion

This study showed that thanks to the explicit training on the

use of the cognitive strategies along with the implementation of the

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Bueno Hernandez

Sheltered Instruction principles, the role of the teacher and the students

was turned 180 degrees; the teacher could separate from lectures and

create more dynamic activities, and the students were the owners of

their learning. The class was more motivating and students developed

a love for learning when the strategies encouraged them. Thus, the use

of strategies became a factor for motivation and students’ motivation

fostered the use of strategies; this was a cycle. However, it is important

to know how to apply the strategies, especially carrying out a scaffolding

process to ensure good results. The cognitive strategies use generated a

better class structure and increased students’ level of understanding and

enjoyment. Finally, it can be said that implementing learning strategies

in any class is a great way of complementing instruction and making

learning easier and delightful for students.

References

Chamot, A., Barnhardt, S., Beard, P., & Robbins, J. (1999). The learning

strategies handbook. New York: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

Chamot, A., Dale, M., O’Malley, J., & Spanos, G. (1993). Learning

and problem solving strategies of ESL students. Bilingual Research

Quaterly, Vol. 16 No. 3&4, 1-38.

Diaz, M. (2010). SIOP Model Strategies: An Approach to Effective

Science Learning of Middle School Students. Unpublished

manuscript.

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2004). Making Content

Comprehensible for English Learners: the SIOP Model (2nd

Edition). Boston, US: Pearson Education, Inc.

Hart, J., & Lee, O. (2003). Teacher professional development to

improve the science and literacy achievement of english language

learners. Bilingual Research Journal, Vol. 27, No.3.

Lee, O. (2005). Science education with English language learners:

synthesis and research agenda. Review of Educational Research,

Vol. 75, No. 4.

Okada, M., Oxford, R., & Abo, S. (1996). Not all alike: Motivation 145

and learning strategies among students of Japanese and Spanish: An

exploratory study. Language learning Motivation: Pathways to the

New Century. Manoa: University of Hawai’i Press.

O’Malley, J. M., & Chamot, A.U. (1990). Learning strategies in second

language acquisition. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University

Press.

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

Teaching Science in English through Cognitive Strategies

Oxford, R., & Nyikos, M. (1989). Variables affecting choices of

language learning strategies by university students. The modern

Language journal, Vol.3, No.73.

Park, G. P. (1997). Language learning strategies and English proficiency

in Korean university students. Foreign language annals Vol. 30, No. 2.

Peregoy, S., & Boyle, O. (2003). Reading, writing and reading in ESL:

a resource book for k-12 teachers. United States of America: Pearson

Education, Inc.

Takeuchi, O. (1993). Language learning strategies and their relationship

to achievement in English as a foreign language. Language

laboratory 30: 17-34.

Varela, F. (1997). Speaking solo: using learning strategy instruction

to improve English language learners’ oral presentation skills in

content-based ESL. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Georgetown

University, Washington, DC.

Author

* Yuli Andrea Bueno holds a B.A in Bilingual Education

from ÚNICA. She currently works as a teacher for the Centro

Colombo Americano in Bogotá.

Email: sopia_170@hotmail.com

146

No. 6 (Nov. 2012)

You might also like

- Space Ship, Planes and First Entry Into Rainbow CityDocument15 pagesSpace Ship, Planes and First Entry Into Rainbow CityNikša Stanojević100% (1)

- A Study of Dylan ThomasDocument5 pagesA Study of Dylan ThomasAna-Maria AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Magnets and Electromagnets WorksheetDocument19 pagesMagnets and Electromagnets WorksheetSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- IXL - Learn 2nd Grade ScienceDocument2 pagesIXL - Learn 2nd Grade ScienceSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Effective Teaching MethologyDocument4 pagesEffective Teaching Methologyrobertson_izeNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument10 pagesResearch ProposalMa. Kristel Orboc100% (1)

- The Problem Background of The ProblemDocument73 pagesThe Problem Background of The ProblemNoel LacambraNo ratings yet

- The Structured Method of Pedagogy: Effective Teaching in the Era of the New Mission for Public Education in the United StatesFrom EverandThe Structured Method of Pedagogy: Effective Teaching in the Era of the New Mission for Public Education in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Bricks Reading 240 Nonfiction - L1 - WB - Answer KeyDocument18 pagesBricks Reading 240 Nonfiction - L1 - WB - Answer KeyNathan HNo ratings yet

- Panganiban, J.:: Ramos v. Ramos G.R. No. 144294. 11 March 2003Document8 pagesPanganiban, J.:: Ramos v. Ramos G.R. No. 144294. 11 March 2003paolo manaloNo ratings yet

- Rules For Significant FiguresDocument7 pagesRules For Significant FiguresJoeleo Aldrin SupnetNo ratings yet

- Improving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic JournalDocument11 pagesImproving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic JournalViophiLightGutNo ratings yet

- Q2 W1 DLL Earth and Life Science EditedDocument3 pagesQ2 W1 DLL Earth and Life Science EditedAiralyn Valdez - Malla100% (1)

- Analysis - Operational Definition Biology 2006-2018Document3 pagesAnalysis - Operational Definition Biology 2006-2018Norizan DarawiNo ratings yet

- The English Teaching Strategies For Young LearnersDocument13 pagesThe English Teaching Strategies For Young LearnersMuzlifatulNo ratings yet

- Case Digest (Sept. 29)Document5 pagesCase Digest (Sept. 29)Jose Li ToNo ratings yet

- Tema 25Document10 pagesTema 25vanesa_duque_3No ratings yet

- The Use of Scientific Approach in Teaching English AsDocument6 pagesThe Use of Scientific Approach in Teaching English AsProfesor IndahNo ratings yet

- Lbs 303-Research Paper FinalDocument9 pagesLbs 303-Research Paper Finalapi-403088205No ratings yet

- Analysis of Learning Strategies in The Speaking Class at The Second Grade 678' (176 2) Senior High SchoolDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Learning Strategies in The Speaking Class at The Second Grade 678' (176 2) Senior High SchoolZein AbdurrahmanNo ratings yet

- Inquiry Based LearningDocument4 pagesInquiry Based LearningBrigitta AdnyanaNo ratings yet

- Work Research FramE BIEN EscuelaDocument48 pagesWork Research FramE BIEN EscuelaJosé D. Vacacela RamónNo ratings yet

- Karil Sastra InggrisDocument12 pagesKaril Sastra InggrisyasiriadyNo ratings yet

- Pia Praxis Team 08Document48 pagesPia Praxis Team 08Miranda BustosNo ratings yet

- A. The Background of The ProblemDocument16 pagesA. The Background of The ProblemtasroniNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Strategi Pembelajaran Dan GayaDocument19 pagesPengaruh Strategi Pembelajaran Dan GayaTaufiq FadaNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Teaching Literature: Students in Focus: April 2015Document11 pagesStrategies in Teaching Literature: Students in Focus: April 2015Rex De Jesus BibalNo ratings yet

- My Proposal QualitativeDocument9 pagesMy Proposal QualitativeGhinaldi AnharNo ratings yet

- Focus of Research-Team08Document7 pagesFocus of Research-Team08Miranda BustosNo ratings yet

- en Language Learning Strategy Taxonomy UsedDocument10 pagesen Language Learning Strategy Taxonomy UsedAndi Ahmad FarawangsahNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology Language Teac 1Document4 pagesResearch Methodology Language Teac 1Danna GomezNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Penerapan Metode Cluster Theme Flashcard Terhadap Peningkatan Vocabulary Bahasa InggrisDocument27 pagesPengaruh Penerapan Metode Cluster Theme Flashcard Terhadap Peningkatan Vocabulary Bahasa InggrisRafli Maulana LubisNo ratings yet

- Teaching EnglishDocument16 pagesTeaching EnglishAli Shimal KzarNo ratings yet

- Phase 2 Teacher SkillsDocument22 pagesPhase 2 Teacher SkillsRosalinda Perez100% (1)

- The Implementation of Scientific Approach in Teaching English in Senior High School PekanbaruDocument12 pagesThe Implementation of Scientific Approach in Teaching English in Senior High School Pekanbaruzahniar niarNo ratings yet

- E-Journal Program Pascasarjana Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris (Volume 2 Tahun 2014)Document12 pagesE-Journal Program Pascasarjana Universitas Pendidikan Ganesha Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris (Volume 2 Tahun 2014)Dewi LestariNo ratings yet

- Discovery Strategies in English Listening Skills Based On The Use of Technological DevicesDocument10 pagesDiscovery Strategies in English Listening Skills Based On The Use of Technological DevicesLUIS FELIPE TOMALA HERRERANo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Yessi - 3 YessDocument41 pagesChapter 1 Yessi - 3 Yesssugeng riyantoNo ratings yet

- 30-Article Text-7-3-10-20201104Document5 pages30-Article Text-7-3-10-20201104Randy PatajanganNo ratings yet

- An Experimental Study of Learner Autonomy in Language LearningDocument18 pagesAn Experimental Study of Learner Autonomy in Language LearningMaria Victoria PadroNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Strategies in Teaching Reading ComprehensionDocument12 pagesTeachers' Strategies in Teaching Reading ComprehensionMeisyita QothrunnadaNo ratings yet

- Achoy Articulo6Document31 pagesAchoy Articulo6Jose Luis Vazquez (Chato)No ratings yet

- Article 209075Document5 pagesArticle 209075KKN UNISNU UNWAHAS SUKOREJONo ratings yet

- Problems and Exploration of Task-Based Teaching in Primary School English TeachingDocument4 pagesProblems and Exploration of Task-Based Teaching in Primary School English TeachingHamida SariNo ratings yet

- Improving Speaking Ability by Using Series of PictureDocument25 pagesImproving Speaking Ability by Using Series of PictureRemo ArdiantoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1and 2Document29 pagesChapter 1and 2MichaelaNo ratings yet

- PDF With Cover Page v2Document13 pagesPDF With Cover Page v2ShamisoNo ratings yet

- Conclusion GraziellaDocument3 pagesConclusion GraziellaAnne MarielNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Cooperative Learning Strategy On English Reading Skills of 9TH Grade Yemeni Students and Their Attitudes Towards The StrategyDocument18 pagesThe Effect of Cooperative Learning Strategy On English Reading Skills of 9TH Grade Yemeni Students and Their Attitudes Towards The StrategyImpact Journals100% (1)

- Learners' Attitudes Towards Using Communicative Approach in Teaching English at Wolkite Yaberus Preparatory SchoolDocument13 pagesLearners' Attitudes Towards Using Communicative Approach in Teaching English at Wolkite Yaberus Preparatory SchoolIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Desta F I PPT EditedDocument39 pagesDesta F I PPT Editedhandisodesta296No ratings yet

- BILINGUALISM E-WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesBILINGUALISM E-WPS OfficeChristina Alexis AristonNo ratings yet

- Ulfah Mariatul Kibtiah - 181230175 - UtseltDocument21 pagesUlfah Mariatul Kibtiah - 181230175 - UtseltUlfah. Mariatul.kNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal 113438Document6 pagesResearch Proposal 113438Dianne Degamo BSED Eng. 2BNo ratings yet

- Task 1Document7 pagesTask 1Nestor AlmanzaNo ratings yet

- Abrham Agize ProposalDocument31 pagesAbrham Agize ProposalBarnababas BeyeneNo ratings yet

- Final Action Research For PrintingDocument21 pagesFinal Action Research For PrintingJeurdecel Laborada Castro - MartizanoNo ratings yet

- Oral CompetenceDocument17 pagesOral CompetenceCyrill MironNo ratings yet

- Autonomous PDFDocument12 pagesAutonomous PDFJane Jauculan MaghinayNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment AlDocument9 pagesFinal Assignment AlHiền Anh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Elec 1 - Lubigan, Angel Rose D.Document3 pagesElec 1 - Lubigan, Angel Rose D.Angel Rose LubiganNo ratings yet

- Bab 5 ReferencesDocument11 pagesBab 5 ReferencesasriNo ratings yet

- .Trashed 1672561753 6302 15856 2 PBDocument12 pages.Trashed 1672561753 6302 15856 2 PBTasya ElvieNo ratings yet

- 104968-Article Text-283922-1-10-20140704Document13 pages104968-Article Text-283922-1-10-20140704walid ben aliNo ratings yet

- The Use of Posse Strategy To Improve Students' Reading Comprehension of Eighth Graders at Mts N 8 Sleman in The Academic Year 2017/2018Document8 pagesThe Use of Posse Strategy To Improve Students' Reading Comprehension of Eighth Graders at Mts N 8 Sleman in The Academic Year 2017/2018Vermina LeniNo ratings yet

- Proposal OkeDocument38 pagesProposal OkeSabar SayaNo ratings yet

- 7623 21431 1 SMDocument13 pages7623 21431 1 SMdelfiasuskselaNo ratings yet

- Instructional Practices Used by Secondary School Teachers in Improving The Skills in English LanguageDocument17 pagesInstructional Practices Used by Secondary School Teachers in Improving The Skills in English LanguagePsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- JURNAL BAHASA INGGRIS SemiinarDocument8 pagesJURNAL BAHASA INGGRIS SemiinarLimaTigaNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument8 pagesChapter Irica sugandiNo ratings yet

- Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsFrom EverandMultilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- Convection Current Worksheet (Specimen IGCSE)Document2 pagesConvection Current Worksheet (Specimen IGCSE)Syakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- 101 Easy and Inexpensive ActivitiesDocument47 pages101 Easy and Inexpensive ActivitiesSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning Tools: Problem-Based Learning Pedagogy and Strategies Are Used To Implement Project-Based ScienceDocument7 pagesProblem-Based Learning Tools: Problem-Based Learning Pedagogy and Strategies Are Used To Implement Project-Based ScienceSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- The Human Nervous System: A Framework For Teaching and The Teaching BrainDocument11 pagesThe Human Nervous System: A Framework For Teaching and The Teaching BrainSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Pendulum PinoleDocument9 pagesPendulum PinoleSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Lesson by Lesson Guide Magnetism & Electricity: (FOSS Kit)Document37 pagesLesson by Lesson Guide Magnetism & Electricity: (FOSS Kit)Syakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Branca Zio 1985Document6 pagesBranca Zio 1985Syakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Physics of Sound: Curriculum Guide ForDocument39 pagesPhysics of Sound: Curriculum Guide ForSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Basic Physics Content With AnswersDocument10 pagesBasic Physics Content With AnswersSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Mazur 2009Document2 pagesMazur 2009Syakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Parthasarathy 2015 Phys. Educ. 50 358Document10 pagesParthasarathy 2015 Phys. Educ. 50 358Syakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

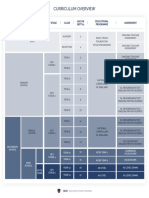

- Curriculum Overview: School Level Key Stage Class Age On Sept 01 Educational Programme AssessmentDocument1 pageCurriculum Overview: School Level Key Stage Class Age On Sept 01 Educational Programme AssessmentSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- SMP Global Prestasi: Project AssignmentDocument4 pagesSMP Global Prestasi: Project AssignmentSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Alonzo2009 PDFDocument33 pagesAlonzo2009 PDFSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Here PicsDocument14 pagesHere PicsSyakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Maltheis 1992Document12 pagesMaltheis 1992Syakti PerdanaNo ratings yet

- Fm-Ro-31-02 - Application For Transcript of Records (BS)Document1 pageFm-Ro-31-02 - Application For Transcript of Records (BS)CardoNo ratings yet

- Aeroflex Replacements WPDocument12 pagesAeroflex Replacements WPVikram ManiNo ratings yet

- MCQ For AminDocument21 pagesMCQ For AminKailali Polytechnic Institute100% (2)

- UCO BankDocument30 pagesUCO BankRonak Singh0% (1)

- Updated Mark PMDocument10 pagesUpdated Mark PMRoy MokNo ratings yet

- Detailed Map - Revised 4 17 14cDocument2 pagesDetailed Map - Revised 4 17 14cHuntArchboldNo ratings yet

- Jenny Kate Tome: Rob-B-HoodDocument5 pagesJenny Kate Tome: Rob-B-HoodDarcy Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Mulanay Ii - Ibabang Yuni Es - 108928Document15 pagesMulanay Ii - Ibabang Yuni Es - 108928MA. GLAIZA ASIANo ratings yet

- Designing Aluminium CansDocument5 pagesDesigning Aluminium CansAsghar Ali100% (1)

- Listening Text Usp 2023Document4 pagesListening Text Usp 2023ekaanggun370No ratings yet

- IBISWorld Video Games Industry Report PDFDocument48 pagesIBISWorld Video Games Industry Report PDFsangaru raviNo ratings yet

- DLL G6 Tleia Q3 W8Document7 pagesDLL G6 Tleia Q3 W8Jose Pasag ValenciaNo ratings yet

- The Weber Grill Magazine: So Much More Than Just A GrillDocument40 pagesThe Weber Grill Magazine: So Much More Than Just A GrillZheng JiangNo ratings yet

- TSB Gen 049Document3 pagesTSB Gen 049Trọng Nghĩa VõNo ratings yet

- Shoe IndustryDocument10 pagesShoe Industryakusmarty100% (1)

- Architectural CompetitionsDocument15 pagesArchitectural CompetitionsShailendra PrasadNo ratings yet

- Preference of Consumer in Selected Brands of Chocolates: Conducted For Economics ProjectDocument13 pagesPreference of Consumer in Selected Brands of Chocolates: Conducted For Economics ProjectAditi Mahale100% (4)

- Notes On Kitchen Organization - Grade 11 - Hotel Management - Kitchen PDFDocument6 pagesNotes On Kitchen Organization - Grade 11 - Hotel Management - Kitchen PDFPooja ReddyNo ratings yet

- James O'Brien: Summary of QualificationsDocument3 pagesJames O'Brien: Summary of Qualificationsapi-303211994No ratings yet

- Internet of Things in Industries A SurveyDocument7 pagesInternet of Things in Industries A SurveySachin PatilNo ratings yet

- NEH Education Summer Programs 2014Document33 pagesNEH Education Summer Programs 2014Richard G. FimbresNo ratings yet