Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Negras in Brazil Review PDF

Negras in Brazil Review PDF

Uploaded by

Juliana GóesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Negras in Brazil Review PDF

Negras in Brazil Review PDF

Uploaded by

Juliana GóesCopyright:

Available Formats

200 ❙ Book Reviews

though traditional notions of gender made women’s political activism less

visible, “black women’s politics maintained a special vision of a racially

equal society” and “black women’s politics informed the debate on au-

thentic blackness and the future of the race” (135). It would take the

passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, a worldwide depression, and the

New Deal to once again make black women’s political activism a visible

and viable force in the fight for racial equality.

Both All Bound Up Together and Private Politics and Public Voices are

compelling accounts of black women’s activism during critical periods in

American history. Both studies successfully delineate the large-scale efforts

of black women’s grassroots organizing and offer important conclusions

about African American women’s political activism. ❙

Negras in Brazil: Re-envisioning Black Women, Citizenship, and the Politics

of Identity. By Kia Lilly Caldwell. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University

Press, 2007.

Violence in the City of Women: Police and Batterers in Bahia, Brazil. By

Sarah J. Hautzinger. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Mariza Corrêa, Unicamp, Brazil

G ender and race seem to form an inescapable mixture when one writes

about Brazil. These two books look at them in quite distinct ways,

however. One seems to search for a lost identity, the other for a new

one. Both look at women, mostly black, and both discuss ideological or

physical violence against them. But while the first seeks to understand

violence committed by a white elite against black people, the second seeks

to understand domestic violence, violence committed by those who are

part of the same community—sometimes pitting black men against black

women.

Kia Lilly Caldwell tries to show that the “use of essentialist discourses

and practices offers a means of challenging hegemonic nationalist dis-

courses which are premised on racial anti-essentialism” (179). The move

seems complicated, but it is also part of a cultural war going on, and not

just in Brazil. In order to dispense with the traditionally evoked Brazilian

notion of “an ostensibly fluid and nonpolar color continuum” (36) as a

This content downloaded from 128.119.202.227 on March 08, 2018 17:05:00 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

S I G N S Autumn 2008 ❙ 201

form of “mestiço essentialism” (28), her book is looking for race in a

place where it seems that race has dissolved into the air—or rather into

flesh of all colors. As she insists on the “reality of race” (10), Caldwell

runs counter not only to today’s scientific reasoning and to historical

accounts of a very hybrid Brazilian society (including its elite) but also to

the beliefs of the women she interviewed. She admits that she had difficulty

“locating self-identified mulheres negras [black women]” (15), or Afro-

Brazilian ones, a notion that has never quite gained currency in Brazilian

politics. So, she turned to women of the Brazilian black movement, some

of whom adopted a black identity (essentialism) “to escape the ‘alienating

symbolic reality’ offered by Brazilian color categories” (115). She defines

this strategy as “racial anti-essentialism” (179). Faced with racism as a

political phenomenon, Caldwell never deals with it as such but instead

tries to anchor it in racial differences. In so doing she fails to pursue the

more promising lines offered by some of the women she talked with, who

pointed to the political nature of the discussion of “race” as a changeable

phenomenon, so much so that it has even affected black hairstyles over

the last twenty years. This means that race may be used as a political

identity tag—as many other identities were—for many purposes, even to

promote access to equal rights, as was the case with the black movement,

or the black women’s movement, in Brazil. This political use of identity

tags was also adopted by gay, female, and indigenous activists. So, when

a student of any color shade uses the quota system to gain inclusion in a

certain institution, he may be making use of a political tool for self-

promotion rather than a manifesto for the African diaspora.

It is true—meaning, historically documented—that Brazil had, and has,

an elite that identifies itself with white Europeans; that some members of

this elite in the nineteenth century supported the value of “whitening”

in order to foresee a “better future” for the country; and that “racial

hybridity” and “racial democracy” are not necessary synonyms—as it is

true also that racism, not race, is everywhere present in Brazil. But Bra-

zilian history—and, by the way, its musical history—is much richer and

more textured than shown here, and contests over identities are a good

part of it. Caldwell oversimplifies the dynamics of race in Brazil, not

recognizing the complexity of the language in songs. For example, she

writes, without blinking, that “markers of blackness . . . are largely

denigrated ” (39; emphasis added), finds “benign” overtly racist songs

(105), as well as misunderstanding the meanings of many other songs or

words (nêga, a shorter term for negra, used as an amorous locution, is a

case in point). As the expression she chooses to translate from a popular

This content downloaded from 128.119.202.227 on March 08, 2018 17:05:00 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

202 ❙ Book Reviews

carnival song, “Your hair gives you away” (O teu cabelo não nega), her

treatment of the Portuguese language and Brazilian people give her away

as a very interested party in the cultural wars on race.

Even though she experienced at least two situations in Brazil like the

ones suffered by Ruth Landes more than fifty years before—being treated

as a prostitute and called Americana (American)—Caldwell does not

evoke the name of Landes, one of the best-known students of Brazilian

black women. Sarah Hautzinger evokes Landes from the beginning—

using the title of her book (City of Women) as a part of the title of her

own.1 But Hautzinger uses it tongue in cheek, as it were, since she wants

to understand how such brave women, as depicted by Landes, can be

victims of aggression in their own city: “How does one resolve the seem-

ingly contradictory trends of resistant, indomitable women on one hand,

and domineering, bullying men on the other?” (22). What follows is a

fascinating ethnography done in Bahia in order to try to answer this

question but, first of all, to try to better formulate others, such as “Would

violence be necessary if men seeking to dominate women were not faced

with women’s noncompliance?” (174). Acknowledging the difficulty of

understanding the “complex, shifting, and context-sensitive terminologies

for color and features that Brazilians employ” (25), Hautzinger observes

that “‘blackness,’ of course, has no fixed, transnational meaning” (26).

But the principal aim of her work—which was carried out in the favelas

(slums) and in the delegacias das mulheres (women’s police stations), first

created in 1985—is to follow in the steps of the original argument made

by Maria Filomena Gregori in her book Cenas e queixas, best summarized

in Jean-Paul Sartre’s boutade (witticism) about women: “half victims, half

accomplices, as everybody else.”2 At the time (1992), Gregori’s book had

a pretty harsh reception from some more traditional feminists, who, like

Caldwell, favored the victimization perspective when dealing with the

question of battered (or black) women. “Mutual violence,” writes Haut-

zinger, “where women may themselves use violence as a way of asserting

themselves or refusing dominance, as well as men’s compensatory violence,

where violence is used more as damage control than to secure dominance,

also requires attention” (31).

Hautzinger’s creative use of the influence of African heritage in the

interpretation of conflicts—inspired by the work of J. Lorand Matory—

1

Ruth Landes, The City of Women (New York: Macmillan, 1947).

2

Maria Filomena Gregori, Cenas e queixas: Um estudo sobre mulheres, relações violentas

e a prática feminista [Scenes and complaints: A study of women, violent relations, and feminist

practice] (São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1993).

This content downloaded from 128.119.202.227 on March 08, 2018 17:05:00 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

S I G N S Autumn 2008 ❙ 203

also deserves to be mentioned. For instance, a man accused of aggression

against his wife excuses himself in the delegacia, saying that he was not

beating his wife but rather defending himself against Oxossi, a masculine

deity of the hunt, who took possession of her. She also terms the ideology

of female superiority professed by the baianas (Bahian women) as Ian-

sãismo, after Iansã, the Afro-Brazilian goddess who is “the fierce controller

of storms” (67), to contrast it with the so-called Marianismo, which refers

to the Virgin Mary’s influence throughout Latin America.

More to the point, however, is her valiant discussion of “the myth of

classlessness of domestic violence” (34). Avoiding the pitfalls of reading

class as race, or race as culture, Hautzinger offers a lucid analysis of the

fact that “the stresses that poverty generates hold significance for the

patterning of domestic violence” (35). In so doing, she also points to the

importance of family networks, and of women in these networks, for

concurring with aggression against women. Her splendid description of

a festival held on Saint John’s Day, in which boys and girls, mocking a

forced marriage in a square dance, slap and kiss each other, is a sad re-

minder of the ways in which children get prepared to act their roles later

as adults. But twenty years after her first visit to Brazil, and contrary to

the impression of her earlier works, she feels confident enough to conclude

her book on an optimistic note on the delegacias, reporting a “steady

progress in this newly reborn democracy’s bold experiment” (265).

In a way, each book is a complement of the other in that both give a

clear picture about the race wars going on in academe and in other fields:

the battles of those who would like to see the Brazilian situation in large

strokes of black and white against those who are looking to the myriad

situations that may divide, as well as connect, people along color, or

gender, lines, more often than not combined with other social markers.

Qualities and failures from one side may be seen as failures and qualities

from the other—but no reader from this side of America will be aloof at

this scene. ❙

This content downloaded from 128.119.202.227 on March 08, 2018 17:05:00 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

You might also like

- Wharton Consulting Club Case Book 2019Document201 pagesWharton Consulting Club Case Book 2019guilhermetrinco64% (14)

- George M. Fredrickson - The Black Image in The White Mind - The Debate On Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914 - Wesleyan University Press (1987)Document355 pagesGeorge M. Fredrickson - The Black Image in The White Mind - The Debate On Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914 - Wesleyan University Press (1987)Anonymous n63qo7A100% (3)

- Seduction or Rape: Deconstructing The Black Female Body in Harriet Jacobs' Incidents in The Life of A Slave GirlDocument18 pagesSeduction or Rape: Deconstructing The Black Female Body in Harriet Jacobs' Incidents in The Life of A Slave Girl2077 HQNo ratings yet

- Adrienne Davis Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' PrincipleDocument12 pagesAdrienne Davis Don't Let Nobody Bother Yo' PrinciplegonzaloluyoNo ratings yet

- RaveenaDocument32 pagesRaveenaHEMANTH KUMAR KNo ratings yet

- Turpin Strategic - Disruptions Black - Feminism Intersectionality AfrofuturismDocument21 pagesTurpin Strategic - Disruptions Black - Feminism Intersectionality AfrofuturismsuudfiinNo ratings yet

- West - Black Postmodern PracticesDocument3 pagesWest - Black Postmodern PracticesGray FisherNo ratings yet

- AP World History Chapter 19-22 Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument14 pagesAP World History Chapter 19-22 Multiple Choice QuestionsSamanthaNo ratings yet

- Black Sexual PoliticsDocument2 pagesBlack Sexual PoliticsFabiana H. ShimabukuroNo ratings yet

- La Prieta HandoutDocument1 pageLa Prieta HandoutTessa Lou Fix0% (1)

- Christen A Smith Towards A Black Feminist Model of Black Atlantic Liberation Remembering Beatriz NascimentoDocument18 pagesChristen A Smith Towards A Black Feminist Model of Black Atlantic Liberation Remembering Beatriz NascimentoElizabeth GarciaNo ratings yet

- Negative Attitude To Teens Promotes Sedentary LifestylesDocument10 pagesNegative Attitude To Teens Promotes Sedentary LifestylesÁlvaro Sánchez100% (1)

- The Autobiography of My Mother: Re-Conceptualization of Race and Agency in Jamaica Kincaid'SDocument14 pagesThe Autobiography of My Mother: Re-Conceptualization of Race and Agency in Jamaica Kincaid'SSruthi AnandNo ratings yet

- BB3 - The Presence and Absence of RaceDocument19 pagesBB3 - The Presence and Absence of RaceAtentamente La PalomanegraNo ratings yet

- Black Feminism UNIT 2Document29 pagesBlack Feminism UNIT 2MehaNo ratings yet

- All Balck Lives Matter Book ReviewDocument4 pagesAll Balck Lives Matter Book ReviewBrian MaregedzeNo ratings yet

- The Identity Crisis and The African AmerDocument25 pagesThe Identity Crisis and The African AmerMouhamadou DemeNo ratings yet

- Why "Womanism"? The Genesis of A New Word and What It MeansDocument17 pagesWhy "Womanism"? The Genesis of A New Word and What It MeansDinesh Shanth YogarajanNo ratings yet

- Private (Brown) Eyes: Ethnicity, Genre and Gender in Crime Fiction in The Gloria Damasco Novels and TheDocument13 pagesPrivate (Brown) Eyes: Ethnicity, Genre and Gender in Crime Fiction in The Gloria Damasco Novels and TheValeria AndradeNo ratings yet

- Fiol-Matta, Licia. A Queer Mother For The Nation. The State and Gabriela Mistral. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. (Objetivo)Document4 pagesFiol-Matta, Licia. A Queer Mother For The Nation. The State and Gabriela Mistral. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. (Objetivo)RodiaSorinNo ratings yet

- AFOLABI - Interfacial Archetypes in Afro-Brazilian - Márcio Barbosa Paulo Colina and Salgado Maranhão 2012Document22 pagesAFOLABI - Interfacial Archetypes in Afro-Brazilian - Márcio Barbosa Paulo Colina and Salgado Maranhão 2012Gustavo TanusNo ratings yet

- Black Marxism, Creative Intellectuals and Culture: The 1930sDocument18 pagesBlack Marxism, Creative Intellectuals and Culture: The 1930sMiguel GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Dissertation Survey - Race in The Urban Latin AmericaDocument6 pagesAssignment: Dissertation Survey - Race in The Urban Latin AmericaBeatriz MartinezNo ratings yet

- Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association Rocky Mountain ReviewDocument19 pagesRocky Mountain Modern Language Association Rocky Mountain ReviewAkhila AkhiNo ratings yet

- Sample Student Response #2 Linving For The RevolutionDocument2 pagesSample Student Response #2 Linving For The RevolutionMery OrmeñoNo ratings yet

- (m2c) The History of Black Feminism and WomanismDocument9 pages(m2c) The History of Black Feminism and Womanismtanima_kumariNo ratings yet

- The Quest of Racial Identity in Song of SolomonDocument41 pagesThe Quest of Racial Identity in Song of SolomonDonet M ThomasNo ratings yet

- Tereza JiroutováDocument19 pagesTereza JiroutováFederica BuetiNo ratings yet

- FLOR - Racism and Sexism Make Black Women The Lowest-Paid Group in BrailDocument8 pagesFLOR - Racism and Sexism Make Black Women The Lowest-Paid Group in BrailBruna TrianaNo ratings yet

- DuBois - PDF Double ConsciousnessDocument20 pagesDuBois - PDF Double ConsciousnessRabeb Ben HaniaNo ratings yet

- From Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle-Class PerformancesFrom EverandFrom Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle-Class PerformancesNo ratings yet

- Final HistDocument19 pagesFinal Histapi-510714748No ratings yet

- Early-19th-Century Literature: American Literary Scholarship January 2006Document25 pagesEarly-19th-Century Literature: American Literary Scholarship January 2006PriyaNo ratings yet

- 2004 Wade Images of Latin American MestizajeDocument12 pages2004 Wade Images of Latin American MestizajeMariano VillalbaNo ratings yet

- Alarcon BridgeDocument15 pagesAlarcon BridgeViviane MarocaNo ratings yet

- Our History Has Always Been Contraband: In Defense of Black StudiesFrom EverandOur History Has Always Been Contraband: In Defense of Black StudiesNo ratings yet

- The SCU of Alabama and Black ConsciousnessDocument29 pagesThe SCU of Alabama and Black ConsciousnessChristopher EbyNo ratings yet

- Order Order No. A1212-01Document8 pagesOrder Order No. A1212-01Mc McAportNo ratings yet

- Gucci Geishas PDFDocument28 pagesGucci Geishas PDFYusepeNo ratings yet

- (SECOND DRAFT) Lit 650 7-1 Final Project II Milestone I - Academic Essay DraftDocument25 pages(SECOND DRAFT) Lit 650 7-1 Final Project II Milestone I - Academic Essay DraftTom HopkinsNo ratings yet

- From Invisibility To Unmarking: Reflections On African-American LiteratureDocument14 pagesFrom Invisibility To Unmarking: Reflections On African-American LiteratureaanndmaiaNo ratings yet

- Dismantling RacismDocument10 pagesDismantling RacismjohnNo ratings yet

- Unloosened Forms, Untranslatable Concerns and Unformed: The Limits of American Notions of Race in Amitav Ghosh's Sea of PoppiesDocument35 pagesUnloosened Forms, Untranslatable Concerns and Unformed: The Limits of American Notions of Race in Amitav Ghosh's Sea of PoppiesNandini DharNo ratings yet

- IntersectionalityDocument15 pagesIntersectionalityGabriel BrahmNo ratings yet

- Paschel MobilizationDocument42 pagesPaschel MobilizationDinah Orozco HerreraNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On African American LiteratureDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On African American Literaturerpmvtcrif100% (1)

- Sacrifice, Love, and Resistance: The Hip Hop Legacy of Assata Shakur Lisa M. CorriganDocument13 pagesSacrifice, Love, and Resistance: The Hip Hop Legacy of Assata Shakur Lisa M. CorriganElizabeth Alarcón-GaxiolaNo ratings yet

- The Afro American Novel (An Overview of 2000-2021)Document8 pagesThe Afro American Novel (An Overview of 2000-2021)yeah yeah oh ohNo ratings yet

- A Black Jurist in a Slave Society: Antonio Pereira Rebouças and the Trials of Brazilian CitizenshipFrom EverandA Black Jurist in a Slave Society: Antonio Pereira Rebouças and the Trials of Brazilian CitizenshipNo ratings yet

- Guess Who's Not Coming To Dinner: A Feminist Reconsideration of "The Dinner Party"Document4 pagesGuess Who's Not Coming To Dinner: A Feminist Reconsideration of "The Dinner Party"carolyn6302100% (1)

- Black Feminist ThoughtDocument7 pagesBlack Feminist ThoughtGerald Akamavi100% (2)

- A savage song: Racist violence and armed resistance in the early twentieth-century U.S.–Mexico BorderlandsFrom EverandA savage song: Racist violence and armed resistance in the early twentieth-century U.S.–Mexico BorderlandsNo ratings yet

- (FIRST DRAFT) Lit 650 7-1 Final Project II Milestone I - Academic Essay DraftDocument23 pages(FIRST DRAFT) Lit 650 7-1 Final Project II Milestone I - Academic Essay DraftTom HopkinsNo ratings yet

- Black Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-ThinkingFrom EverandBlack Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-ThinkingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Rodriguez 2016 Transforming - Anthropology PDFDocument9 pagesRodriguez 2016 Transforming - Anthropology PDFNorma Luz Gonzalez RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Multiple Oppressions Through PDFDocument8 pagesTheorizing Multiple Oppressions Through PDFMaster of ShadeNo ratings yet

- Black and White FemisimDocument5 pagesBlack and White FemisimHagit PatrickNo ratings yet

- Afro Pessimism Core - SDI 2015Document47 pagesAfro Pessimism Core - SDI 2015BobSpaytanNo ratings yet

- Conquering Discourses of Sexual Conquest of Women Language and MestizajeDocument27 pagesConquering Discourses of Sexual Conquest of Women Language and Mestizajejocelyn2203No ratings yet

- Beyond The Flesh: Contemporary Representations of The Black Female Body in Afro-Brazilian LiteratureDocument30 pagesBeyond The Flesh: Contemporary Representations of The Black Female Body in Afro-Brazilian LiteratureFlavia SantosNo ratings yet

- A Message To American Negroes - Manoel PasaoDocument4 pagesA Message To American Negroes - Manoel PasaoJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Negras in Brazil Chapter 1Document26 pagesNegras in Brazil Chapter 1Juliana GóesNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument1 pageUntitledJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Prophetic Naming As Informal Adult Education - Decolonizing The Imagination With Boston's New Majority PDFDocument370 pagesProphetic Naming As Informal Adult Education - Decolonizing The Imagination With Boston's New Majority PDFJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Prophetic Naming As Informal Adult Education - Decolonizing The Imagination With Boston's New Majority PDFDocument370 pagesProphetic Naming As Informal Adult Education - Decolonizing The Imagination With Boston's New Majority PDFJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- OntocideDocument29 pagesOntocideJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Blurring BoundersDocument43 pagesBlurring BoundersJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey Juris Book ReviewDocument4 pagesJeffrey Juris Book ReviewJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- After Empire - Fernando CoronilDocument33 pagesAfter Empire - Fernando CoronilJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Oxford Scholarship Online: Party/Politics: Horizons in Black Political ThoughtDocument24 pagesOxford Scholarship Online: Party/Politics: Horizons in Black Political ThoughtJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Freyre in USADocument17 pagesFreyre in USAJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Du Bois and Three Race TheoriesDocument38 pagesDu Bois and Three Race TheoriesJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- WeberDocument19 pagesWeberJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- (Cap. 1) VAN EVERA, S. Hypotheses, Laws and Theories - An User PDFDocument22 pages(Cap. 1) VAN EVERA, S. Hypotheses, Laws and Theories - An User PDFJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Verbete Civil SocietyDocument6 pagesVerbete Civil SocietyJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

- Verbete Quality DemocracyDocument7 pagesVerbete Quality DemocracyJuliana GóesNo ratings yet

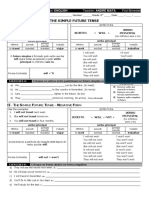

- Correção Dos Exercícios Do Livro DidáticoDocument9 pagesCorreção Dos Exercícios Do Livro DidáticoSandra Patrícia Miranda da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Reports 1Document10 pagesReports 1sam98678No ratings yet

- Brazil Restructuring of The Oil Gas IndustryDocument9 pagesBrazil Restructuring of The Oil Gas Industrykiane43No ratings yet

- RC Passages - 8Document28 pagesRC Passages - 8abhimanyu_bhatia_2No ratings yet

- LAFER, Celso, 2000. Brazilian International Identity and Foreign Policy PDFDocument21 pagesLAFER, Celso, 2000. Brazilian International Identity and Foreign Policy PDFBruno PasquarelliNo ratings yet

- Teaching ResumeDocument2 pagesTeaching Resumeapi-255326299No ratings yet

- Av. Lúcio Meira, 233. Várzea, Teresópolis (RJ) 25953-002Document34 pagesAv. Lúcio Meira, 233. Várzea, Teresópolis (RJ) 25953-002Humberto FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics of HungerDocument4 pagesAesthetics of HungerAnonymousFarmerNo ratings yet

- Ai! Que Saudades Da Amélia-Saxofone AltoDocument2 pagesAi! Que Saudades Da Amélia-Saxofone AltoWalter RodrigoNo ratings yet

- Allegation To The Global Compact Dam Collapse in BrumadinhoDocument10 pagesAllegation To The Global Compact Dam Collapse in BrumadinhoJefferson NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Brazil USAIDDocument10 pagesBrazil USAIDChristopher JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Alden Dauril From Colony To Nation Essays On The Independence of Brazil by Russell Wood PDFDocument3 pagesAlden Dauril From Colony To Nation Essays On The Independence of Brazil by Russell Wood PDFDermeval MarinsNo ratings yet

- Making Samba by Marc A. HertzmanDocument36 pagesMaking Samba by Marc A. HertzmanDuke University Press0% (1)

- Sugar Manufacturing Companies BrazilDocument2 pagesSugar Manufacturing Companies BrazilIsk TornadoNo ratings yet

- English 1Document65 pagesEnglish 1Naveen PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Carey - Alcohol in The AtlanticDocument47 pagesCarey - Alcohol in The AtlanticDomingoGarciaNo ratings yet

- Isd Rates UninorDocument35 pagesIsd Rates UninorDrManojkumar BhoomigariNo ratings yet

- Brazil Aging Full Eng FinalDocument204 pagesBrazil Aging Full Eng FinalJohn DoeNo ratings yet

- Santo DaimeDocument19 pagesSanto DaimeVictor CironeNo ratings yet

- GW - SB2 - Answer KeyDocument21 pagesGW - SB2 - Answer KeyMatthew GalliganNo ratings yet

- JBS Day Transcription - 2013 and 4Q13 ResultsDocument35 pagesJBS Day Transcription - 2013 and 4Q13 ResultsJBS RINo ratings yet

- 8a Sc3a9rie One Day The Simple Future TenseDocument5 pages8a Sc3a9rie One Day The Simple Future TenseFernanda MotaNo ratings yet