Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

Uploaded by

M SCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

Uploaded by

M SCopyright:

Available Formats

New 2018

American College of Radiology

ACR Appropriateness Criteria®

Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

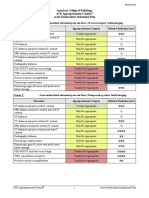

Variant 1: Postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain, localized to the deep pelvis. Initial imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

US pelvis transvaginal Usually Appropriate O

US duplex Doppler pelvis Usually Appropriate O

US pelvis transabdominal Usually Appropriate O

MRI pelvis without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O

CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢

CT pelvis with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢

MRI pelvis without IV contrast May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O

CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV

Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢

contrast

CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

CT pelvis without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢

CT pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

Radiography abdomen and pelvis Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

Variant 2: Postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain, clinically suspected pathologies in

perineum, vulva, or vagina. Initial imaging.

Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level

US duplex Doppler pelvis Usually Appropriate O

US pelvis transabdominal Usually Appropriate O

US pelvis transvaginal Usually Appropriate O

MRI pelvis without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate O

MRI pelvis without IV contrast May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O

CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV

Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢

contrast

CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

CT pelvis with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

CT pelvis without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢

CT pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

Radiography abdomen and pelvis Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

POSTMENOPAUSAL SUBACUTE OR CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

Expert Panel on Women’s Imaging: Katherine E. Maturen, MD, MSa; Esma A. Akin, MDb; Mark Dassel, MDc;

Sandeep Prakash Deshmukh, MDd; Kika M. Dudiak, MDe; Tara L. Henrichsen, MDf;

Lee A. Learman, MD, PhDg; Edward R. Oliver, MD, PhDh; Liina Poder, MDi; Elizabeth A. Sadowski, MDj;

Hebert Alberto Vargas, MDk; Therese M. Weber, MDl; Tom Winter, MDm; Phyllis Glanc, MD.n

Summary of Literature Review

Introduction/Background

Chronic pelvic pain, defined as cyclical or noncyclical pain involving the pelvis, lower abdomen, vulva, vagina,

or perineum and lasting for at least 6 months, affects as many as a quarter of women worldwide and is the single

most common presenting complaint at gynecologic office visits [1,2]. The morbidity, public health impact, and

downstream costs are substantial but poorly quantified in part due to the large variety of etiologies and lack of

definitions associated with chronic pelvic pain. For purposes of this document, the term “subacute” is added to

distinguish our target entities from diagnoses that most commonly present with acute or even emergent

symptoms. This guideline is limited to postmenopausal women, which further limits the range of potential pain

etiologies.

Subacute or chronic pelvic pain is a broad clinical presentation common to a variety of gynecologic, urinary,

gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal disorders. There are specific ACR Appropriateness Criteria documents

pertaining to many of these diagnoses, which are detailed in Appendix 1. In particular, we emphasize the

importance of both vaginal bleeding and suspected adnexal mass in postmenopausal women because of the

prevalence of endometrial and ovarian neoplasia in this age group. These clinical features, if present, should take

precedence over the general complaint of pelvic pain in directing the management algorithm. Patients with acute

pain, suspected pelvic floor dysfunction, or urinary complaints may be managed in accordance with the respective

algorithms for those conditions. Imaging evaluation for suspected endometriosis is not considered here as

endometriosis is estrogen dependent and usually regresses after menopause [3]. If a postmenopausal woman is

experiencing pain from endometriosis, it is likely secondary to scarring or reactivation that is due to

postmenopausal hormonal therapy. In cases of persistent endometriosis-related symptoms after menopause,

readers are referred to ACR Appropriateness Criteria guidance for the premenopausal age group (see Appendix 1).

Finally, like other types of chronic pain, pelvic pain is a complex process with incompletely mapped cognitive

and neurologic contributors. As such, there is a growing body of literature regarding potential use of neurologic

imaging in patients with chronic pelvic pain [4-7]. However, central nervous system functional imaging remains

in the research domain for evaluation of chronic pelvic pain at this time, so we will not consider it formally

among the discussed imaging procedures.

When all of these aspects of subacute and chronic pelvic pain in postmenopausal women are excluded from direct

consideration, a handful of clinically significant conditions remain. We group these according to location of

clinical symptoms: pain localized to the deep or internal pelvis, with potential etiologies and associated

conditions, including pelvic venous disorders (commonly termed pelvic congestion syndrome), intraperitoneal

adhesions, hydrosalpinx, chronic inflammatory disease, or cervical stenosis versus chronic pain localized to the

perineum, vulva, or vagina that arises from suspected vaginal atrophy, vaginismus, vaginal or vulvar cysts,

vulvodynia, or pelvic myofascial pain.

Special Imaging Considerations

When there is suspected local pathology in the vulva, perineum, or vaginal wall, translabial/transperineal

ultrasound (US) or side-firing transvaginal probes may provide better visualization than end-firing transvaginal

a

Panel Chair, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. bGeorge Washington University Hospital, Washington, District of Columbia. cCleveland Clinic,

Cleveland, Ohio; American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. dThomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. eMayo Clinic,

Rochester, Minnesota. fMayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. gFlorida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida; American Congress of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists. hChildren’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

i

University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California. jUniversity of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin. kMemorial Sloan Kettering Cancer

Center, New York, New York. lUniversity of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama. mUniversity of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. nSpecialty Chair,

University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

The American College of Radiology seeks and encourages collaboration with other organizations on the development of the ACR Appropriateness

Criteria through society representation on expert panels. Participation by representatives from collaborating societies on the expert panel does not necessarily

imply individual or society endorsement of the final document.

Reprint requests to: publications@acr.org

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 2 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

US probes [8]. There is scant evidence for imaging recommendations at this level of specificity, and it is assumed

that the performing sonographer and sonologist will make appropriate technical adjustments to optimize imaging

in these relatively uncommon clinical scenarios.

Discussion of Procedures by Variant

Variant 1: Postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain, localized to the deep pelvis. Initial imaging.

Radiography Abdomen and Pelvis

To our knowledge, there is currently no evidence to support the use of radiography to evaluate postmenopausal

subacute or chronic pelvic pain localized to the deep pelvis.

US Pelvis Transvaginal

Pelvic US using a combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach is the initial imaging study of choice to

evaluate postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain localized to the deep pelvis [9-12]. US can provide

anatomic information about uterine size and endometrial canal distension, fallopian tube dilation, ovaries, and

adnexal masses. Regarding the sequencing of examinations, several authors have pointed out that if the etiology

of pelvic pain remains obscure after CT, a subsequent US has the capacity to provide additional information about

the adnexa in particular [13,14]. US is broadly used and clinically accepted worldwide. However, high-quality

evidence, such as clinical trials supporting specific usefulness of US, is lacking.

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease may be associated with pelvic fluid, hydrosalpinx or pyosalpinx,

inflammatory adnexal masses, and peritoneal inclusions visible by US [15]. When pelvic adhesions are suspected,

real-time dynamic US or cine clips may document abnormal adherence or lack of mobility of structures,

particularly transvaginally. However, adhesive disease is a notoriously difficult diagnosis to confirm

nonoperatively [16], and the evidence basis is anecdotal [15,17]. Furthermore, the causal linkage between

adhesive disease and chronic pelvic pain remains unclear.

US Pelvis Transabdominal

As above, a combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach is most appropriate for pelvic imaging,

combining the anatomic overview provided by the transabdominal approach with the greater spatial and contrast

resolution of transvaginal imaging. These techniques should be performed together whenever possible. Please see

the “US Pelvis Transvaginal” section for further details.

US Duplex Doppler Pelvis

Color and spectral Doppler are routinely employed in pelvic sonography to evaluate internal vascularity of pelvic

observations and distinguish fluid and cysts from soft tissue. Although it is rated as a separate imaging procedure

per ACR methodology, the expert panel considers Doppler imaging to be a standard component of pelvic

sonography. Special considerations for women with chronic pelvic pain may include evaluation of uterine artery

blood flow with low-resistance waveforms in women with chronic pelvic pain [12] and altered venous flow in the

setting of pelvic congestion. When pelvic venous disorders are suspected clinically, color and spectral Doppler

evaluation may be used to document engorged periuterine and periovarian veins (≥8 mm), low-velocity flow,

altered flow with Valsalva maneuver, retrograde (caudal) flow of the ovarian veins, and direct connection

between engorged pelvic veins and myometrial arcuate veins [9-11]. Increased pelvic vascularity may also be

present in the setting of uterine or tubo-ovarian neoplasia; these guidelines assume normal imaging appearance of

the pelvic organs.

Many women with pelvic venous disorders have morphologic findings of polycystic ovarian syndrome (enlarged

ovaries with exaggerated central stroma and multiple small peripherally located follicles), but the associated

clinical features of hirsutism and amenorrhea are rare [11,18]. Multiple investigators have identified a component

of estrogen overstimulation in pelvic venous disorders, and symptoms may subside after menopause in some

women [15]. There is a lack of clear definition and high-quality evidence in the clinical domain of pelvic venous

disorders.

CT Abdomen and Pelvis

When pelvic venous disorders are clinically suspected, contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis may

demonstrate engorged periuterine and periovarian veins, venous anatomic variants, and occasional compression of

the left renal vein resulting in asymmetric left-sided pelvic varicosities [10,19-22]. However, CT lacks the

capacity of US or MR to provide dynamic flow information [18].

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 3 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

In chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, CT may demonstrate pelvic fluid, peritoneal thickening, hydrosalpinx or

pyosalpinx, and even tubo-ovarian abscess [23]. CT has the capacity to demonstrate architectural distortion and

tethering in adhesive disease, but CT sensitivity and specificity for this diagnosis have not been documented to

our knowledge. When adhesive disease is severe, small-bowel obstruction may result, and CT of the abdomen and

pelvis with intravenous (IV) contrast is the imaging examination of choice. See Appendix 1 for the ACR

Appropriateness Criteria® for “Suspected Small-Bowel Obstruction.”

CT Pelvis

When pelvic venous disorders are clinically suspected, contrast-enhanced CT of the pelvis may demonstrate

engorged periuterine and periovarian veins, although their drainage into the renal vein or cava will not be

evaluated without CT coverage of the abdomen [10,19-22]. In chronic inflammatory disease, CT may demonstrate

pelvic fluid, peritoneal thickening, hydrosalpinx or pyosalpinx, and tubo-ovarian abscess [23].

MRI Pelvis

MRI is widely regarded as the problem-solving imaging examination of choice for chronic pelvic pain,

particularly when US findings are nondiagnostic or inconclusive [11,15,24]. When MRI is clinically indicated, the

use of a gadolinium-based IV contrast agent is preferred. Please see the ACR Manual on Contrast Media for

additional information [25].

The diagnostic performance of MRI/MR angiography is comparable to conventional venography for identifying

pelvic venous disorders [26,27]. The use of MRI for this indication is growing accordingly [28], necessitating

standardized interpretation and reporting [29]. T2-weighted imaging has the capacity to demonstrate pelvic

varices, but signal intensity varies with flow velocity. Vein conspicuity and flow directional assessment are

superior using time-resolved postcontrast T1-weighted imaging, which can directly demonstrate ovarian vein

reflux [10,30]. Noninvasive imaging with MRI has largely supplanted conventional venography for diagnostic

purposes, but venography may still be performed in the context of intended intervention.

In chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, MRI with T2-weighted imaging may demonstrate edema, fluid

collections, and distension of endometrial canal or fallopian tubes [15]. When infection is long standing,

distinguishing between inflammatory and neoplastic masses is particularly difficult. Postcontrast T1-weighted

imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging are particularly important in this setting [23]. Adhesive disease may be

directly evident at MRI as low-signal bands between structures on nonfat saturated T2-weighted imaging or

inferred in the presence of peritoneal inclusion cysts [11,15].

Variant 2: Postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain, clinically suspected pathologies in perineum,

vulva, or vagina. Initial imaging.

Physical examination is the foundation of clinical evaluation of suspected pathology in the perineum, vulva, or

vagina. The evidence supporting the use of imaging procedures in this clinical context largely assumes that the

physical examination is abnormal.

Radiography Abdomen and Pelvis

To our knowledge, there is currently no evidence to support the use of radiography to evaluate postmenopausal

subacute or chronic pelvic pain localized to the perineum, vulva, or vagina.

US Pelvis Transvaginal

Physical examination is the basis of diagnosis for most conditions localized to the vulvar skin [31]. Perineal and

vaginal cysts are subcutaneous but often palpable and are appropriately evaluated with either translabial or

transvaginal US, or both [8]. As with pelvic pain localized to the deep pelvis, US is widely regarded as the initial

imaging study of choice for pelvic pain localized to the perineum, vulva, or vagina, but there is little high-quality

evidence specifically supporting its use.

US Pelvis Transabdominal

As above, a combined transabdominal and transvaginal approach is most appropriate for pelvic imaging,

combining the anatomic overview provided by the transabdominal approach with the greater spatial and contrast

resolution of transvaginal imaging. These techniques should be performed together whenever possible. Please see

the “US Pelvis Transvaginal” section for further details.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 4 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

US Duplex Doppler Pelvis

Color and spectral Doppler are routinely used in pelvic sonography to evaluate internal vascularity of pelvic

observations and distinguish cysts from soft tissue. Although it is rated as a separate imaging procedure per ACR

methodology, the expert panel considers Doppler imaging to be a standard component of pelvic sonography.

Special considerations for women with chronic pelvic pain may include evaluation of uterine artery blood flow,

with low-resistance waveforms having been described in women with chronic pelvic pain [12].

CT Abdomen and Pelvis

To our knowledge, there is currently no evidence to support the use of CT for primary evaluation of

postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain localized to the perineum, vulva, or vagina.

CT Pelvis

To our knowledge, there is currently no evidence to support the use of CT for primary evaluation of

postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain localized to the perineum, vulva, or vagina.

MRI Pelvis

When MRI is clinically indicated, the use of a gadolinium-based IV contrast agent is preferred. Please see the

ACR Manual on Contrast Media for additional information [25].

When a cyst or mass is identified by US in the perineum, vulva, or vagina, MRI provides additional anatomic

detail and evaluation of any enhancing soft-tissue components that might favor infection or neoplasia

[11,24,32,33]. MRI has an important role as a problem-solving examination for lesion characterization and

surgical planning, but there is, to our knowledge, no direct evidence to support the use of MRI as the initial or

primary imaging examination for evaluation of pelvic pain localized to the perineum, vulva, or vagina,

particularly when the physical examination is normal. However, there is emerging evidence to support the first-

line utility of MRI when endometriosis or fistulizing disease are suspected [34]; readers are again referred to

specific ACR Appropriateness Criteria guidelines for these clinical scenarios (see Appendix 1).

MRI also enables accurate depiction of pelvic floor muscular anatomy, integrity, and function [35,36]. Pelvic

floor dysfunction is discussed in detail in a separate ACR Appropriateness Criteria document (see Appendix 1),

but specific note is made here of the usefulness of MRI for assessment of muscular hypertonicity in chronic pelvic

pain syndromes [37].

Summary of Recommendations

Variant 1: US pelvis transvaginal, US duplex Doppler pelvis, and US pelvis transabdominal are usually

appropriate for the initial imaging of postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain localized to the deep

pelvis. These procedures are complementary and should be performed together.

Variant 2: US duplex Doppler pelvis, US pelvis transvaginal, and US pelvis transabdominal are usually

appropriate for the initial imaging of postmenopausal subacute or chronic pelvic pain with clinically

suspected pathologies in the perineum, vulva, or vagina. These procedures are complementary and should be

performed together.

Summary of Evidence

Of the 38 references cited in the ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic

Pain document, all of them are categorized as diagnostic references including 1 well-designed study, 4 good-

quality studies, and 10 quality studies that may have design limitations. There are 23 references that may not be

useful as primary evidence.

The 38 references cited in the ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

document were published from 2005 to 2017.

Although there are references that report on studies with design limitations, 5 well-designed or good-quality

studies provide good evidence.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 5 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

Appropriateness Category Names and Definitions

Appropriateness

Appropriateness Category Name Appropriateness Category Definition

Rating

The imaging procedure or treatment is indicated in

Usually Appropriate 7, 8, or 9 the specified clinical scenarios at a favorable risk-

benefit ratio for patients.

The imaging procedure or treatment may be

indicated in the specified clinical scenarios as an

May Be Appropriate 4, 5, or 6 alternative to imaging procedures or treatments with

a more favorable risk-benefit ratio, or the risk-benefit

ratio for patients is equivocal.

The individual ratings are too dispersed from the

panel median. The different label provides

May Be Appropriate transparency regarding the panel’s recommendation.

5

(Disagreement) “May be appropriate” is the rating category and a

rating of 5 is assigned.

The imaging procedure or treatment is unlikely to be

indicated in the specified clinical scenarios, or the

Usually Not Appropriate 1, 2, or 3 risk-benefit ratio for patients is likely to be

unfavorable.

Relative Radiation Level Information

Potential adverse health effects associated with radiation exposure are an important factor to consider when

selecting the appropriate imaging procedure. Because there is a wide range of radiation exposures associated with

different diagnostic procedures, a relative radiation level (RRL) indication has been included for each imaging

examination. The RRLs are based on effective dose, which is a radiation dose quantity that is used to estimate

population total radiation risk associated with an imaging procedure. Patients in the pediatric age group are at

inherently higher risk from exposure, both because of organ sensitivity and longer life expectancy (relevant to the

long latency that appears to accompany radiation exposure). For these reasons, the RRL dose estimate ranges for

pediatric examinations are lower as compared to those specified for adults (see Table below). Additional

information regarding radiation dose assessment for imaging examinations can be found in the ACR

Appropriateness Criteria® Radiation Dose Assessment Introduction document [38].

Relative Radiation Level Designations

Adult Effective Dose Estimate Pediatric Effective Dose Estimate

Relative Radiation Level*

Range Range

O 0 mSv 0 mSv

☢ <0.1 mSv <0.03 mSv

☢☢ 0.1-1 mSv 0.03-0.3 mSv

☢☢☢ 1-10 mSv 0.3-3 mSv

☢☢☢☢ 10-30 mSv 3-10 mSv

☢☢☢☢☢ 30-100 mSv 10-30 mSv

*RRL assignments for some of the examinations cannot be made, because the actual patient doses in these procedures vary

as a function of a number of factors (eg, region of the body exposed to ionizing radiation, the imaging guidance that is

used). The RRLs for these examinations are designated as “Varies”.

Supporting Documents

For additional information on the Appropriateness Criteria methodology and other supporting documents go to

www.acr.org/ac.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 6 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

References

1. Ahangari A. Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: an updated review. Pain Physician

2014;17:E141-7.

2. Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gulmezoglu M, Khan KS. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic

pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health 2006;6:177.

3. Gemmell LC, Webster KE, Kirtley S, Vincent K, Zondervan KT, Becker CM. The management of

menopause in women with a history of endometriosis: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2017:1-20.

4. Bagarinao E, Johnson KA, Martucci KT, et al. Preliminary structural MRI based brain classification of

chronic pelvic pain: A MAPP network study. Pain 2014;155:2502-9.

5. Berman SM, Naliboff BD, Suyenobu B, et al. Reduced brainstem inhibition during anticipated pelvic visceral

pain correlates with enhanced brain response to the visceral stimulus in women with irritable bowel

syndrome. J Neurosci 2008;28:349-59.

6. Borg C, Georgiadis JR, Renken RJ, Spoelstra SK, Weijmar Schultz W, de Jong PJ. Brain processing of visual

stimuli representing sexual penetration versus core and animal-reminder disgust in women with lifelong

vaginismus. PLoS One 2014;9:e84882.

7. Gupta A, Rapkin AJ, Gill Z, et al. Disease-related differences in resting-state networks: a comparison between

localized provoked vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and healthy control subjects. Pain 2015;156:809-

19.

8. Shobeiri SA, Rostaminia G, White D, Quiroz LH, Nihira MA. Evaluation of vaginal cysts and masses by 3-

dimensional endovaginal and endoanal sonography. J Ultrasound Med 2013;32:1499-507.

9. Cicchiello LA, Hamper UM, Scoutt LM. Ultrasound evaluation of gynecologic causes of pelvic pain. Obstet

Gynecol Clin North Am 2011;38:85-114, viii.

10. Ganeshan A, Upponi S, Hon LQ, Uthappa MC, Warakaulle DR, Uberoi R. Chronic pelvic pain due to pelvic

congestion syndrome: the role of diagnostic and interventional radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol

2007;30:1105-11.

11. Kuligowska E, Deeds L, 3rd, Lu K, 3rd. Pelvic pain: overlooked and underdiagnosed gynecologic conditions.

Radiographics 2005;25:3-20.

12. Somprasit C, Tanprasertkul C, Suwannarurk K, Pongrojpaw D, Chanthasenanont A, Bhamarapravatana K.

Transvaginal color Doppler study of uterine artery: is there a role in chronic pelvic pain? J Obstet Gynaecol

Res 2010;36:1174-8.

13. Patel MD, Dubinsky TJ. Reimaging the female pelvis with ultrasound after CT: general principles.

Ultrasound Q 2007;23:177-87.

14. Yitta S, Mausner EV, Kim A, et al. Pelvic ultrasound immediately following MDCT in female patients with

abdominal/pelvic pain: is it always necessary? Emerg Radiol 2011;18:371-80.

15. Juhan V. Chronic pelvic pain: An imaging approach. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015;96:997-1007.

16. Tabibian N, Swehli E, Boyd A, Umbreen A, Tabibian JH. Abdominal adhesions: A practical review of an

often overlooked entity. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;15:9-13.

17. Silva PD, Suarez SA. A Case of Disabling Urinary Frequency and Pelvic Pain Due to Postoperative Uterine

Adhesions. WMJ 2016;115:43-5.

18. Ignacio EA, Dua R, Sarin S, et al. Pelvic congestion syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Semin Intervent

Radiol 2008;25:361-8.

19. Karaosmanoglu D, Karcaaltincaba M, Karcaaltincaba D, Akata D, Ozmen M. MDCT of the ovarian vein:

normal anatomy and pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:295-9.

20. Koc Z, Ulusan S, Oguzkurt L. Right ovarian vein drainage variant: is there a relationship with pelvic varices?

Eur J Radiol 2006;59:465-71.

21. Koc Z, Ulusan S, Oguzkurt L. Association of left renal vein variations and pelvic varices in abdominal

MDCT. Eur Radiol 2007;17:1267-74.

22. Wang R, Yan Y, Zhan S, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian vein syndrome (OVS) by computed tomography (CT)

imaging: a retrospective study of 11 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e53.

23. Thomassin-Naggara I, Darai E, Bazot M. Gynecological pelvic infection: what is the role of imaging? Diagn

Interv Imaging 2012;93:491-9.

24. Valentini AL, Gui B, Basilico R, Di Molfetta IV, Micco M, Bonomo L. Magnetic resonance imaging in

women with pelvic pain from gynaecological causes: a pictorial review. Radiol Med 2012;117:575-92.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 7 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

25. American College of Radiology. Manual on Contrast Media. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Clinical-

Resources/Contrast-Manual. Accessed September 30, 2018.

26. Asciutto G, Mumme A, Marpe B, Koster O, Asciutto KC, Geier B. MR venography in the detection of pelvic

venous congestion. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;36:491-6.

27. Yang DM, Kim HC, Nam DH, Jahng GH, Huh CY, Lim JW. Time-resolved MR angiography for detecting

and grading ovarian venous reflux: comparison with conventional venography. Br J Radiol 2012;85:e117-22.

28. Leiber LM, Thouveny F, Bouvier A, et al. MRI and venographic aspects of pelvic venous insufficiency.

Diagn Interv Imaging 2014;95:1091-102.

29. Bharwani N, Tirlapur SA, Balogun M, et al. MRI reporting standard for chronic pelvic pain: consensus

development. Br J Radiol 2016;89:20140615.

30. Dick EA, Burnett C, Anstee A, Hamady M, Black D, Gedroyc WM. Time-resolved imaging of contrast

kinetics three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance venography in patients with pelvic congestion syndrome.

Br J Radiol 2010;83:882-7.

31. van der Meijden WI, Boffa MJ, Ter Harmsel WA, et al. 2016 European guideline for the management of

vulval conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:925-41.

32. Hwang JH, Oh MJ, Lee NW, Hur JY, Lee KW, Lee JK. Multiple vaginal mullerian cysts: a case report and

review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:137-9.

33. Surabhi VR, Menias CO, George V, Siegel CL, Prasad SR. Magnetic resonance imaging of female urethral

and periurethral disorders. Radiol Clin North Am 2013;51:941-53.

34. Tirlapur SA, Daniels JP, Khan KS. Chronic pelvic pain: how does noninvasive imaging compare with

diagnostic laparoscopy? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2015;27:445-8.

35. Quinn M. Injuries to the levator ani in unexplained, chronic pelvic pain. J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;27:828-31.

36. Savoye-Collet C, Koning E, Dacher JN. Radiologic evaluation of pelvic floor disorders. Gastroenterol Clin

North Am 2008;37:553-67, viii.

37. Ackerman AL, Lee UJ, Jellison FC, et al. MRI suggests increased tonicity of the levator ani in women with

interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Int Urogynecol J 2016;27:77-83.

38. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Radiation Dose Assessment Introduction.

Available at: https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Appropriateness-

Criteria/RadiationDoseAssessmentIntro.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2018.

The ACR Committee on Appropriateness Criteria and its expert panels have developed criteria for determining appropriate imaging examinations for

diagnosis and treatment of specified medical condition(s). These criteria are intended to guide radiologists, radiation oncologists and referring physicians

in making decisions regarding radiologic imaging and treatment. Generally, the complexity and severity of a patient’s clinical condition should dictate the

selection of appropriate imaging procedures or treatments. Only those examinations generally used for evaluation of the patient’s condition are ranked.

Other imaging studies necessary to evaluate other co-existent diseases or other medical consequences of this condition are not considered in this

document. The availability of equipment or personnel may influence the selection of appropriate imaging procedures or treatments. Imaging techniques

classified as investigational by the FDA have not been considered in developing these criteria; however, study of new equipment and applications should

be encouraged. The ultimate decision regarding the appropriateness of any specific radiologic examination or treatment must be made by the referring

physician and radiologist in light of all the circumstances presented in an individual examination.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 8 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

Appendix 1. Related ACR Appropriateness Criteria Topics

Subject area AC topic

Vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal

Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

women

Clinically suspected adnexal mass Clinically Suspected Adnexal Mass

Acute pelvic pain in postmenopausal

Postmenopausal Acute Pelvic Pain – Topic under development

women

Pelvic floor dysfunction Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Endometriosis Infertility

Pelvic inflammatory disease Acute Pelvic Pain in the Reproductive Age Patient

Leiomyomas Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding and Clinically Suspected Adnexal Mass

Urinary tract infection Recurrent Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Women

Endometrial cancer Pretreatment Evaluation and Follow-up of Endometrial Cancer

Vaginal cancer Staging and Follow-up of Vaginal Cancer – Topic under development

Vulvar cancer Staging and Follow-up of Vulvar Cancer – Topic under development

Hematuria Hematuria

Diverticulitis Left Lower Quadrant Pain-Suspected Diverticulitis

Left lower quadrant pain Left Lower Quadrant Pain-Suspected Diverticulitis

Right lower quadrant pain Right Lower Quadrant Pain-Suspected Appendicitis

Suspected small bowel obstruction Suspected Small-Bowel Obstruction

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 9 Postmenopausal Subacute or Chronic Pelvic Pain

You might also like

- Hi Tracy: Total Due Here's Your Bill For JanuaryDocument6 pagesHi Tracy: Total Due Here's Your Bill For JanuaryalexNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Practice Guidelines For Emergency General SurgeryDocument19 pagesDynamic Practice Guidelines For Emergency General SurgeryHarlyn MagsinoNo ratings yet

- PDF. Art Appre - Module 1Document36 pagesPDF. Art Appre - Module 1marvin fajardoNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine BleedingDocument12 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleedingvictor contrerasNo ratings yet

- Hematuria PDFDocument11 pagesHematuria PDFPipitNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitisDocument16 pagesAcute PancreatitisLoredana BoghezNo ratings yet

- Major Blunt TraumaDocument18 pagesMajor Blunt TraumaghassanNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Illness in Immunocompetent PatientsDocument14 pagesAcute Respiratory Illness in Immunocompetent PatientsVianney OlveraNo ratings yet

- Acute Nonlocalized Abdominal PainDocument17 pagesAcute Nonlocalized Abdominal PainghassanNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm-Interventional Planning and Follow-UpDocument13 pagesAbdominal Aortic Aneurysm-Interventional Planning and Follow-Upvictor contrerasNo ratings yet

- Adrenal Mass EvaluationDocument19 pagesAdrenal Mass Evaluationpj rakNo ratings yet

- Acute Nonspecific Chest Pain-Low Probability of Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument10 pagesAcute Nonspecific Chest Pain-Low Probability of Coronary Artery Diseasevictor contrerasNo ratings yet

- Low Back PainDocument22 pagesLow Back PainSF TifarinNo ratings yet

- Occupational Lung DiseasesDocument13 pagesOccupational Lung DiseasesVianney OlveraNo ratings yet

- Acute Hip Pain-Suspected FractureDocument9 pagesAcute Hip Pain-Suspected FractureMario UmañaNo ratings yet

- Breast PainDocument9 pagesBreast PainmarysrbNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Follow-Up (Without Repair)Document7 pagesAbdominal Aortic Aneurysm Follow-Up (Without Repair)victor contrerasNo ratings yet

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria Pancreatic CystDocument9 pagesACR Appropriateness Criteria Pancreatic CystSole GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Suspected Spine TraumaDocument25 pagesSuspected Spine TraumaFelix Valerian HalimNo ratings yet

- Onset Flank PainDocument11 pagesOnset Flank PainPipitNo ratings yet

- Aaa RepairDocument5 pagesAaa RepairLakshmi Mounica GrandhiNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Truama (Handout)Document6 pagesAbdominal Truama (Handout)Ayuub AbdirizakNo ratings yet

- Second and Third Trimester Screening For Fetal AnomalyDocument12 pagesSecond and Third Trimester Screening For Fetal AnomalyIqra NazNo ratings yet

- Imaging AppendicitisDocument75 pagesImaging AppendicitiswilandayuNo ratings yet

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria For HematuriaDocument8 pagesACR Appropriateness Criteria For HematuriaAndrew TaliaferroNo ratings yet

- Intensive Care Unit PatientsDocument12 pagesIntensive Care Unit PatientsMoisés LópezNo ratings yet

- Blunt Trauma Abdomen: (Operative V/S Conservative Management)Document41 pagesBlunt Trauma Abdomen: (Operative V/S Conservative Management)Bhi-An BatobalonosNo ratings yet

- Acute Onset Flank Pain-Suspicion of Stone DiseaseDocument9 pagesAcute Onset Flank Pain-Suspicion of Stone DiseasecubirojasNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Intraabdominal InjuriesDocument88 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Intraabdominal Injuriessgod34No ratings yet

- Indeterminate Renal Mass ACR Appropriateness CriteriaDocument10 pagesIndeterminate Renal Mass ACR Appropriateness CriteriaAndrew TaliaferroNo ratings yet

- Infective EndocarditisDocument13 pagesInfective Endocarditispaquidermo85No ratings yet

- Appendicitis During Pregnancy: Benha University Hospital, EgyptDocument53 pagesAppendicitis During Pregnancy: Benha University Hospital, EgyptWilda HanimNo ratings yet

- Rationale Diagnostic ProceduresDocument22 pagesRationale Diagnostic ProceduresShaktisila FatrahadyNo ratings yet

- Plain Abdominal Radiography in Acute AbdominalDocument27 pagesPlain Abdominal Radiography in Acute AbdominalanisaNo ratings yet

- Trauma Tumpul Abdomen: Stase Bedah Digestif Januari 2019Document49 pagesTrauma Tumpul Abdomen: Stase Bedah Digestif Januari 2019ArifHidayatNo ratings yet

- Acute AbdomenDocument71 pagesAcute AbdomenariNo ratings yet

- 240 243Document5 pages240 243Rika WulandariNo ratings yet

- ER Inguinal Hernia RepairDocument5 pagesER Inguinal Hernia RepairJayzelle Anne de LeonNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Radiologi FixDocument44 pagesJurnal Radiologi FixAfifa Prima GittaNo ratings yet

- Abdomin Al Hernias: Reuben Rhubarbs' TangDocument24 pagesAbdomin Al Hernias: Reuben Rhubarbs' TangReuben TangNo ratings yet

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria Right Upper Quadrant PainDocument9 pagesACR Appropriateness Criteria Right Upper Quadrant PainDoc Tor StrangeNo ratings yet

- Management of Abdominal Trauma: By: Chong Lih YinDocument71 pagesManagement of Abdominal Trauma: By: Chong Lih YinRakaNo ratings yet

- Scrotal PainDocument7 pagesScrotal PainPipitNo ratings yet

- Moola-Ultrasound in OB PDFDocument66 pagesMoola-Ultrasound in OB PDFFarah MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Dr. Franklin - Acute Appendicitis - FDRDocument31 pagesDr. Franklin - Acute Appendicitis - FDRAbel MncaNo ratings yet

- Blunt Abdominal TraumaDocument11 pagesBlunt Abdominal TraumaRahmat SyahiliNo ratings yet

- all noteDocument4 pagesall noteZainab Sidi AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ovarian and Prostate CancerDocument51 pagesOvarian and Prostate CancerMa. Angelica Alyssa RachoNo ratings yet

- Rational Diagnostic Procedures OviDocument12 pagesRational Diagnostic Procedures OviRosfi Firdha HuzaimaNo ratings yet

- 1 Role of Ultrasound in The Evaluation of Acute Pelvic PainDocument11 pages1 Role of Ultrasound in The Evaluation of Acute Pelvic PainGhofran Ibrahim HassanNo ratings yet

- servi noteDocument4 pagesservi noteZainab Sidi AhmedNo ratings yet

- Imaging Patients With Acute Abdominal Pain: RSNA, 2009 Supplemental MaterialDocument46 pagesImaging Patients With Acute Abdominal Pain: RSNA, 2009 Supplemental MaterialAfifa Prima GittaNo ratings yet

- Renal Cell Carcinoma Staging (ACR Appropriateness Criteria)Document10 pagesRenal Cell Carcinoma Staging (ACR Appropriateness Criteria)Andrew TaliaferroNo ratings yet

- Isuog BasisDocument40 pagesIsuog BasisAndreea IonașcuNo ratings yet

- 1.2.2. Emergency Abdominal ImagingDocument51 pages1.2.2. Emergency Abdominal ImagingNoura AdzmiaNo ratings yet

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria JaundiceDocument15 pagesACR Appropriateness Criteria Jaundicesitoxpadang ceriaNo ratings yet

- Abdominal TraumaDocument51 pagesAbdominal TraumaAhmad HasanNo ratings yet

- Imaging of Acute AbdomenDocument16 pagesImaging of Acute AbdomenNilanka SandunNo ratings yet

- AppendicitisDocument11 pagesAppendicitisWildan Farik AlkafNo ratings yet

- Chest XrayDocument6 pagesChest XrayAjit KumarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecologic Emergencies 2022Document16 pagesPediatric and Adolescent Gynecologic Emergencies 2022Felipe MayorcaNo ratings yet

- Flayer SeminarDocument3 pagesFlayer SeminarM SNo ratings yet

- Stepanski2003 Use of Sleep Hygiene in The Treatment of InsomniaDocument11 pagesStepanski2003 Use of Sleep Hygiene in The Treatment of InsomniaM SNo ratings yet

- (Deborah Phillips) Longman Complete Course For TheDocument687 pages(Deborah Phillips) Longman Complete Course For TheM SNo ratings yet

- Psychological And Behavioral Treatment Of Insomnia UpdateDocument17 pagesPsychological And Behavioral Treatment Of Insomnia UpdateM SNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Early Warning SignsDocument1 pageNeonatal Early Warning SignsM SNo ratings yet

- LOMER Et Al-2008-Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics PDFDocument11 pagesLOMER Et Al-2008-Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics PDFM SNo ratings yet

- Patient Education Bloody Stools in ChildrenDocument8 pagesPatient Education Bloody Stools in ChildrenM SNo ratings yet

- Doña PerfectaDocument317 pagesDoña PerfectadracbullNo ratings yet

- Biochemical Aspect of DiarrheaDocument17 pagesBiochemical Aspect of DiarrheaLiz Espinosa0% (1)

- 02-Procedures & DocumentationDocument29 pages02-Procedures & DocumentationIYAMUREMYE EMMANUELNo ratings yet

- Operations Management Dr. Loay Salhieh Case Study #1: Students: Hadil Mosa Marah Akroush Mohammad Rajab Ousama SammawiDocument6 pagesOperations Management Dr. Loay Salhieh Case Study #1: Students: Hadil Mosa Marah Akroush Mohammad Rajab Ousama SammawiHadeel Almousa100% (1)

- BRT vs Light Rail Costs: Which is Cheaper to OperateDocument11 pagesBRT vs Light Rail Costs: Which is Cheaper to Operatejas rovelo50% (2)

- Clique Pen's Marketing StrategyDocument10 pagesClique Pen's Marketing StrategySAMBIT HALDER PGP 2018-20 BatchNo ratings yet

- LEGAL STATUs of A PersonDocument24 pagesLEGAL STATUs of A Personpravas naikNo ratings yet

- Understanding key abdominal anatomy termsDocument125 pagesUnderstanding key abdominal anatomy termscassandroskomplexNo ratings yet

- W220 Engine Block, Oil Sump and Cylinder Liner DetailsDocument21 pagesW220 Engine Block, Oil Sump and Cylinder Liner DetailssezarNo ratings yet

- Metatron AustraliaDocument11 pagesMetatron AustraliaMetatron AustraliaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 018Document12 pagesChapter 018api-281340024No ratings yet

- Final Script Tokoh NilamDocument1 pageFinal Script Tokoh NilamrayyanNo ratings yet

- 14 XS DLX 15 - 11039691Document22 pages14 XS DLX 15 - 11039691Ramdek Ramdek100% (1)

- Theory of Karma ExplainedDocument42 pagesTheory of Karma ExplainedAKASH100% (1)

- 1 PPT - Pavement of Bricks and TilesDocument11 pages1 PPT - Pavement of Bricks and TilesBHANUSAIJAYASRINo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Intro - LatinDocument11 pagesLesson 1 Intro - LatinJohnny NguyenNo ratings yet

- PSP, Modern Technologies and Large Scale PDFDocument11 pagesPSP, Modern Technologies and Large Scale PDFDeepak GehlotNo ratings yet

- C++ Project On Library Management by KCDocument53 pagesC++ Project On Library Management by KCkeval71% (114)

- Wave of WisdomDocument104 pagesWave of WisdomRasika Kesava100% (1)

- D2 Pre-Board Prof. Ed. - Do Not Teach Too Many Subjects.Document11 pagesD2 Pre-Board Prof. Ed. - Do Not Teach Too Many Subjects.Jorge Mrose26No ratings yet

- REBECCA SOLNIT, Wanderlust. A History of WalkingDocument23 pagesREBECCA SOLNIT, Wanderlust. A History of WalkingAndreaAurora BarberoNo ratings yet

- Court Rules on Debt Collection Case and Abuse of Rights ClaimDocument3 pagesCourt Rules on Debt Collection Case and Abuse of Rights ClaimCesar CoNo ratings yet

- Evoe Spring Spa Targeting Climbers with Affordable WellnessDocument7 pagesEvoe Spring Spa Targeting Climbers with Affordable WellnessKenny AlphaNo ratings yet

- Self Respect MovementDocument2 pagesSelf Respect MovementJananee RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- 8086 ProgramsDocument61 pages8086 ProgramsBmanNo ratings yet

- Dislocating The Sign: Toward A Translocal Feminist Politics of TranslationDocument8 pagesDislocating The Sign: Toward A Translocal Feminist Politics of TranslationArlene RicoldiNo ratings yet

- E.Coli Coliforms Chromogenic Medium: CAT Nº: 1340Document2 pagesE.Coli Coliforms Chromogenic Medium: CAT Nº: 1340Juan Manuel Ramos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Endoplasmic ReticulumDocument4 pagesEndoplasmic Reticulumnikki_fuentes_1100% (1)