Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Using Sensory Integration and

Uploaded by

Vero MoldovanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Using Sensory Integration and

Uploaded by

Vero MoldovanCopyright:

Available Formats

Earn .

1 AOTA CEU

(one contact hour and

Education Article 1.25 NBCOT PDU).

See page CE-7 for details.

Using Sensory Integration and Sensory-Based

Occupational Therapy Interventions Across

Pediatric Practice Settings

RENEE WATLING, PHD, OTR/L, FAOTA presents a brief historical perspective of the sensory integra-

Clinical Assistant Professor, Division of Occupational Therapy, tion theory and a description of intervention strategies based

University of Washington on the principles of sensory processing, followed by a discus-

Seattle, Washington sion of the regulatory and contextual factors that influence

Adjunct Faculty, School of Occupational and Physical Therapy, service provision addressing sensory needs across pediatric

University of Puget Sound practice settings.

Tacoma, Washington

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

GLORIA FROLEK CLARK, PHD, OTR/L, BCP, FAOTA OF SENSORY INTEGRATION THEORY

Private Practice A. J. Ayres developed the sensory integration theory in the

Adel, Iowa 1960s and 1970s. Ayres (1972) posited that sensory infor-

mation was nourishment for the nervous system and that

This CE Article was developed in collaboration with the nervous system responded to sensory information with

AOTA’s Sensory Integration Special Interest Section. alterations in function, structure, and output. Thus, sensa-

tion could both inhibit and facilitate brain function and

ABSTRACT occupational behavior. She integrated findings from human

Difficulties in processing and integrating sensory informa- and animal neuroscience, psychology, education, and human

tion can have an effect on occupational performance and development to better understand and delineate the relation-

behavior in the daily lives of children and youth. Services for ship between brain functions, behavior, emotion, and learn-

pediatric clients are influenced by a range of legislative and ing (Ayres, 1972, 1979). She consulted studies examining the

funding policies. Occupational therapy practitioners working effects of sensory deprivation and sensory-enriched environ-

in various pediatric practice settings need knowledge of the ments on physical and emotional behavior. She used this

differences between these approaches and the provisions information to generate hypotheses about the nature of the

of the funding resources in order to best meet the sensory relationship between sensation and typical development, the

processing and integration needs of their clients in various way development could be affected if physiological process-

contexts. ing of sensation was disrupted, and how sensory experiences

could then be used to remediate dysfunction and support

LEARNING OBJECTIVES development (Bundy, Lane, & Murray, 2002).

After reading this article, you should be able to: Ayres tested her hypotheses through research studies and

1. Identify the differences between Ayres’ sensory integra- developed measurement tools to help identify the presence

tion intervention and sensory-based strategies. and nature of sensory dysfunction in children. Her work

2. Recognize provisions of legislative and funding policies for generated the theory of sensory integration, which describes

pediatric occupational therapy services. the relationships between sensation, brain function, and

3. Recognize differences between supporting pediatric behavior; methods for measuring observable manifestations

clients with sensory needs in educational versus clinical of sensory integration processes; and principles for designing

contexts. interventions to address breakdowns in sensory processing

and integration. Since Ayres’ death in 1989, many research-

INTRODUCTION ers and theorists have continued her work, both directly

Difficulties in processing and integrating sensory information and indirectly. Present-day understanding of neuroscience,

can have an effect on occupational performance and behav- psychology, and development supports many of her original

ior in the daily lives of children and youth. Occupational conceptualizations of brain-behavior relationships (Lane &

therapy practitioners working in various pediatric practice Schaaf, 2010).

settings need to be aware of sensory processing, the possible

impact of sensory processing difficulties across behavior and Sensory Processing and Integration

performance areas, and the contextual factors that influence Sensory information arises from multiple sources, both

provision of services to address these needs. This article within and outside of the body. Sensory information from

SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17) ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 CE-1

AOTA Continuing Education Article

CE Article, exam, and certificate are also available ONLINE.

Register at http://www.aota.org/cea or call toll-free 877-404-AOTA (2682).

within the body informs the individual of pain, hunger, or sleep and wake states, and an inability to manage behavioral

other conditions reflecting the state of the physical body. responses. Often, the individual with dysfunction in sensory

Sensory information from external sources yields informa- processing and integration displays behavior that is out of

tion about the characteristics of objects, spatial relationships proportion to a sensory event or experience. For example,

between objects including the body, and movement of the the client may cover his or her ears and cry at the sound of

body or part of the body through space. There are seven a flushing toilet; react with aggression or as if in pain when

forms of sensory input: taste, smell, sight, sound, touch, accidentally bumped; appear to not notice sensory events

movement, and force. These must be registered, processed, noticed by others; or have difficulty grading the amount

and interpreted within the central nervous system in order of force used when interacting with other people, pets, or

for the individual to gain a reference for the body’s rela- objects.

tionship to itself, gravity, and people and objects in the

environment, as well as to perceive the spatial relationships INTERVENTIONS BASED ON

between other people and objects (Ayres, 1972). All sensa- PRINCIPLES OF SENSORY PROCESSING

tion is essential for the individual to develop an awareness of Based on her work with varied clinical populations, Ayres

himself or herself as an integrated whole, and sensation helps posited that sensation could be used intentionally and stra-

build a foundation for learning and developing skills. When tegically to enhance an individual’s ability to detect, register,

an individual effectively processes and integrates sensory perceive, and respond adaptively to stimuli in an organized

information, responses to sensation are purposeful and goal and appropriate manner with regard to cognitive, motor,

directed. The individual is able to register and perceive a social, and emotional responses. She researched and devel-

stimulus, formulate and execute a response to the stimulus, oped strategies for using sensory experiences and environ-

and learn from the success or failure of his or her response. mental modifications to create a foundation for successful

Over time, responses become more mature and complex, occupational engagement and functional performance.

effective and adaptive, and are “efficient, creative, and satis- Sensory integration intervention as described by Ayres

fying” (Ayres, 1979, p. 7). Occupational therapy practitioners (1972, 1979) is characterized by active engagement of the

are concerned with an individual’s ability to engage in occu- client in a range of sensory-based activities that challenge

pational activities that are desired by and meaningful to the the client to respond to environmental cues; register, per-

individual. When a disruption in occupational engagement ceive, and integrate sensation; and produce appropriate and

and performance is noted, it is important that the occupa- adaptive cognitive, emotional, physical, and social responses

tional therapy practitioner consider the possibility that dis- (Ayres, 1972, 1979; Parham et al., 2011; Smith Roley, Mail-

ordered sensory processing or integration is an influencing loux, Miller Kuhaneck, & Glennon, 2007). Ayres (1972, 1979)

factor. Accurate and thorough understanding of how disor- advocated that intervention activities emphasize active

dered sensory processing and integration can affect function engagement with tactile (touch), proprioceptive (pressure

and the manifestations of such dysfunction are crucial for or force), and vestibular (movement) sensations. Other

making these determinations. For further information on sensations (smell, taste, sound, and vision) are also incor-

sensory processing and integration, please see Ayres (1972, porated as they are useful to the individual client. Activities

1979, 2005); Bundy et al. (2002); Smith Roley, Blanche, & range from simple interactions with sensory materials, such

Schaaf (2001); and Schaaf & Davies (2010b). as scooping and pouring dry beans, to complex multisensory

activities, such as planning and navigating obstacle courses

Sensory Integrative Dysfunction of suspended and grounded equipment that challenge adap-

Ayres (1979) described dysfunction in sensory integra- tive occupational behavior in cognitive, motor, regulatory,

tion as a condition in which “the brain is not processing or and social domains. As such, sensory integration interven-

organizing the flow of sensory impulses in a manner that tion requires specialized equipment and environments that

gives the individual good, precise sensory input well...[and] afford a range of dynamic sensory experiences. For example,

is not directing behavior effectively” (p. 51). Thus, ineffec- suspended equipment such as swings, trapeze bars, rope

tive sensory processing interferes with the individual’s ability ladders, and other climbing materials allows engagement

to use sensation as a foundation for function and behavioral in movement activities that challenge balance, equilibrium,

organization. Sensory integration dysfunction is multifaceted, ideation, motor execution, problem solving, and a host of

with individuals displaying clusters of signs and symptoms in other adaptive responses. Equipment and environmental

cognitive, motor, emotional, and social behavior. For exam- modifications are part of the dynamic interplay between the

ple, dysfunction in sensory integration can be the source of occupational therapist, client, and environment in which

ineffective performance in school tasks or social situations, the therapist employs clinical reasoning, critical thinking,

poor use of the body to move through space or interact and therapeutic use of self to intentionally and strategically

with physical objects, an inability to regulate emotional and create opportunities for the client to actively experience

CE-2 ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17)

Earn .1 AOTA CEU (one contact hour and 1.25 NBCOT PDU). See page CE-7 for details.

and engage with sensations, ultimately leading to produc- approach described by Ayres. (See Schaaf & Davies, 2010a,

tion of adaptive responses. Sensory integration intervention 2010b for a more thorough description of the confusion

is designed to address the underlying neurophysiological regarding terminology and the current state of the science of

processing of sensation as the foundation for function and sensory integration theory and intervention.) Recent reviews

requires advanced theoretical knowledge and practical skills. of evidence-based literature have helped to discriminate

Due to the complexity of Ayres’ sensory integration interven- among the published examinations of sensory integration and

tion, specialized postprofessional training and mentorship sensory-based interventions and provide evaluations of the

are highly recommended (Watling, Koenig, Schaaf, & Davies, efficacy of both (see Schaaf & Davies, 2010b).

2011).

Fidelity to Sensory Integration Theory

Sensory-Based Intervention Because of the confusion around terminology and the

At times, occupational therapy practitioners may not have growing use of the phrase sensory integration to refer to

access to the equipment or environments essential for pro- approaches very different from the intervention Ayres devel-

viding sensory integration intervention, or may be working oped, efforts were made to re-establish the term sensory

in contexts in which this approach is not supported. In these integration and to trademark the phrase Ayres Sensory

cases, the sensory needs of clients may be at least partially Integration® (ASI®). Scholars, scientists, and researchers

addressed through sensory-based interventions. Sensory- recognized as experts in sensory integration theory and

based interventions use discrete sensory experiences or envi- practice used systematic procedures to identify the features

ronmental modifications to support regulation of behavior, of the sensory integration intervention process (see Parham

address specific difficulties in sensory modulation or sensory et al., 2007, for a description of the procedures used). This

discrimination, prepare the client for engagement, support work identified and defined core structural and procedural

the ability to focus on learning activities, and regulate client elements of sensory integration intervention (see Table 1).

behavior as task demands change (Tomchek & Case-Smith, These same core elements are the foundation of a fidelity-to-

2009; Watling et al., 2011). For example, sensory-based treatment measurement tool (see Parham et al., 2007, 2011)

strategies include providing a quiet enclosed space for a child that can be used to determine whether an intervention meets

to retreat to when feeling overwhelmed in a busy or noisy

environment, providing compressible or resistive materials

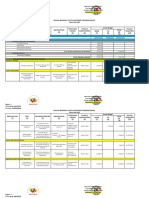

for manipulation to help decrease distraction and increase Table 1. Process and Structural Elements of Ayres’

focused attention on a task, and providing nontraditional Sensory Integration Interventions

seating options such as air-filled cushions or ball chairs Process Elements

that offer movement opportunities while allowing a child to Key therapeutic strategies of an ASI intervention

remain seated during desk work. Sensory-based interven- • Ensures physical safety

tions often aim to focus a child’s attention and promote orga- • Presents sensory opportunities

nized behavior in everyday contexts such as school, home, or • Helps the child attain and maintain appropriate levels of alertness

the community (Watling et al., 2011). Sensory-based inter- • Challenges postural, oral, ocular, or bilateral motor control

ventions are often an integral part of occupational therapy in • Challenges praxis and organization of behavior

early intervention and school-based practices. • Collaborates with the child on activity choices

• Tailors activities to present the just-right challenge

CURRENT CONCEPTS • Ensures that activities are successful

Ayres’ work spurred recognition by many professions of the • Supports the child’s intrinsic motivation to play

critical role that sensation plays in behavior and function. • Establishes a therapeutic alliance with the child

Over the past 40 years, many other theorists and practition-

Structural Elements

ers developed sensory-based methods that are quite different

Commonly documented features of an ASI intervention

from what Ayres developed and described. However, in most

• Therapist qualifications in sensory integration include

instances, there was little to no discriminant discussion or

postprofessional training and mentorship

examination of these methods, and many were referred to

• Record review, including thorough occupational therapy

erroneously as sensory integration methods. This resulted in

evaluation results

widespread and often inappropriate use of the term sen-

• Physical space and equipment affordances, including space

sory integration in the literature, with many publications

for vigorous activity and a variety of suspended equipment

inaccurately being identified as descriptions or examinations

• Ongoing communication with team members, including

of sensory integration intervention. This led to confusion

evidence of parent–therapist collaboration on goal setting

about what sensory integration intervention is and is not, as

well as inaccurate conclusions about the effectiveness of the Note: From Parham et al., 2011

SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17) ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 CE-3

AOTA Continuing Education Article

CE Article, exam, and certificate are also available ONLINE.

Register at http://www.aota.org/cea or call toll-free 877-404-AOTA (2682).

the criteria for being an ASI intervention (Smith Roley et al.,

2007). Table 2. Characteristics of Ayres Sensory Integration and

Sensory-Based Intervention Approaches

Professional Responsibility Ayres Sensory Integration Sensory-Based

Given the confusion around terminology and intervention Intervention Intervention

strategies, it is critical for occupational therapy practitioners

to understand the difference between sensory integration Aims to have a lasting Aims to modify regulatory

and sensory-based strategies and to accurately identify and impact on neurophysiological state or behavior quickly

describe the approach being used in their services. Doing processing of sensation without a lasting effect

so demonstrates personal professionalism as well as the Adheres to core process and Uses sensation to support

scientific rigor of our field. In addition, by understanding the structural elements identified function but does not meet

difference between sensory integration and sensory-based in fidelity-to-treatment fidelity criteria

interventions, the theoretical conceptualizations of each, instrument

and the evidence around each, we are equipped to enter into

dialogue with others and bring clarity of these issues to those Requires active engagement Sensation may be experienced

outside our field. and an adaptive response passively with or without an

As other professions use, advertise, and publish informa- adaptive response

tion about sensory-based approaches, we must understand Requires specialized equipment Minimal equipment needed

and be able to articulate the similarities and differences

between these approaches, ASI, and occupational therapy Requires specialized environ- Easily implemented in

using sensory-based approaches. The different interven- mental affordances everyday environments

tions can produce different outcomes, and expectations

Provided in the context of play May or may not be playful

should be adjusted accordingly. When occupational therapy

practitioners understand the realistic expectations of a Provided in a one-on-one May be administered in

given intervention, we can advocate for and provide the context that allows individual- individual or group contexts

intervention most appropriate for a client and help others to ization and responsive modifi-

understand and appreciate the affordances and limitations of cation of the intervention

each approach. Table 2 identifies some of the key differences

between ASI and sensory-based approaches. Practitioner has advanced Advanced training

training recommended

MAJOR LAWS AND FUNDING SOURCES INFLUENCING Certification recommended

SERVICE PROVISION

Consistent with Ayres Sensory

Providing services that adequately and effectively meet

Integration theory

the sensory needs of pediatric clients with challenges in

processing and integrating sensory information requires

advanced knowledge and skills in this area of practice as well

as knowledge of the various contextual factors that influ- dlers, birth to 3 years of age (Part C), as well as children and

ence provision of services to children. Occupational therapy young adults ages 3 to 21 years who have disabilities (Part

practitioners may provide services for children at home, in B). Part C emphasizes services to children in the natural

school, and in myriad community environments. However, environments, and Part B emphasizes the least restrictive

current legislation and reimbursement regulations often environments. Other differences between Part C and Part B

stipulate parameters within which occupational therapy are delineated below. Funding sources for IDEA services may

services are funded. The next section of this article describes include federal, state, and local special education dollars as

the relevant legislation and corresponding public and private well as Medicaid and private insurance (primarily for Part C

funding resources that influence provision of occupational programs).

therapy services to children in the United States. To advocate IDEA Part C. Part C, also known as early intervention or

for and ethically provide appropriate services, occupational the Infant & Toddler Program, focuses on children and

therapy practitioners must understand the affordances and their families. Early intervention is a 12-month program

limitations of these various resources. that serves children and families throughout the traditional

school year as well as during the summer months. One of the

Educational Legislation and Publically Funded Services primary purposes of Part C programs is to build the capacity

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement of families to care for their infants or toddlers. Because the

Act of 2004 (IDEA) addresses services to infants and tod- law does not mandate states to provide these services, states

CE-4 ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17)

Earn .1 AOTA CEU (one contact hour and 1.25 NBCOT PDU). See page CE-7 for details.

choose whether to participate in this federal program and mance consistently falls below state standards, typical physi-

receive funds. There is wide variability among states regard- cal development, behavioral expectations, or grade level; and

ing the agency that oversees this program, the person provid- educational performance is unique when compared to others

ing service coordination, and the professionals providing the in that setting; and there are no more plausible explana-

services. The definition of developmental disability is set tions, a disability may be suspected and a referral for a full

by each state, so a child could be eligible for this program in and individual evaluation (FIE) is made. Lack of instruction

one state, but not in another. Even funding varies from state or access to instruction, poor attendance, and language or

to state. Some states provide services at no cost to the family, cultural differences need to be ruled out as possible reasons

whereas other states use private insurance and Medicaid as for the delay because these do not constitute a disability. An

funding sources. independent medical or mental health diagnosis may be suffi-

Teams have 45 calendar days after receiving a referral to cient for suspecting a disability; however, the impact of such

complete assessments and to develop the individualized fam- a diagnosis on educational performance must be established

ily service plan (IFSP). Under Part C, assessments include in order for the child to receive special education services.

both family and child measures. Family-directed assessments After the family formally consents to an FIE of their child,

often include interviews to identify the family’s concerns, pri- the team has 60 calendar days to complete evaluations, hold

orities, and resources (such as informal or formal supports). a meeting with the parents, and write the individualized

Families may decline to participate in this assessment and education program (IEP). Team members, including occupa-

still receive early intervention services. Evaluation/assess- tional therapists, who participate in the FIE are required to

ment information is used in determining whether the child use a variety of evaluation tools and strategies. These could

meets the state’s eligibility for this Part C program. Children include observations, interviews, record reviews, and formal

must be evaluated in five domains: adaptive, cognitive, and informal evaluation tools. When difficulties processing

communication, physical, and social development. Physi- and integrating sensory information are suspected, data

cal evaluation may include fine motor, gross motor, hearing, should be gathered using a range of tools as well as across a

vision, and sensory processing skills. In addition, a review of range of school environments and contexts.

the child’s health and nutrition is typically included. In young Federal provisions state that services to help students

children, concerns related to sensory processing and integra- with IEPs transition out of the educational system must

tion may include the child having difficulty with feeding and occur by the time they are 16 years of age. At a minimum,

eating; calming and state regulation; frequent or intense the first IEP in effect when the child turns 16 must include

tantrums; or rigid behaviors that interfere with outings, social measurable postsecondary goals, based on age-appropriate

interaction, or transitions (Watling, Bodison, Henry, & Miller- transition assessments and transition services needed to

Kuhaneck, 2006). assist the child in reaching those goals. For students with

At the IFSP meeting, parents and other members of the challenges processing and integrating sensory information,

early intervention team identify family and child outcomes transition planning should include strategies for managing

as well as services. IDEA requires the IFSP to a include sensory needs in postsecondary settings and contexts. Occu-

a statement of early intervention services based on peer- pational therapy has a critical role in addressing life skills for

reviewed research, to the extent practicable, necessary to many students with special needs and should be included in

meet the unique needs of the infant or toddler and the fam- the transition planning.

ily. To assist with transitioning out of the early intervention

program, an individualized transition plan must be in place at Early Intervening Services

least 90 days before the child’s third birthday. Some children IDEA 2004 also included early intervening services. Local

will transition out of all services; others may transition to education agencies may use up to 15% of their Part B monies

community-based programs or be referred for an evaluation to identify children who are at risk for academic and behavior

to determine eligibility for Part B services. Occupational challenges and to provide support for these students to suc-

therapy is considered a primary service under this law, ceed in the general education environment. IDEA uses the

meaning occupational therapy could be the only service on term early intervening services (EIS) to identify services

a child’s IFSP. Under Part C, occupational therapists may act to general education students and professional develop-

as service coordinators, participate in the evaluation process ment for teachers delivered under this provision. Response

through multi- or transdisciplinary team evaluation, or con- to Intervention (RtI) is the framework used by many states

duct a separate occupational therapy evaluation of the child. for providing services under EIS. Under EIS/RtI, occupational

IDEA Part B. Under IDEA Part B, eligible children ages 3 to therapy practitioners provide services primarily to popula-

21 years are entitled to a free appropriate public education tions or groups. For example, occupational therapists may

(FAPE), including academic instruction and related service train teachers in how sensory processing and integration

provision. In most cases, if a student’s educational perfor- challenges can interfere with learning and behavior and how

SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17) ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 CE-5

AOTA Continuing Education Article

CE Article, exam, and certificate are also available ONLINE.

Register at http://www.aota.org/cea or call toll-free 877-404-AOTA (2682).

sensory-based strategies can support the diverse needs of such as birthday parties; challenges with tactile, vestibular,

many such students. Some children who have mild to moder- and proprioceptive processing can impact praxis and limit a

ate difficulties processing and integrating sensory informa- child’s success in maneuvering through the environment or

tion may display learning challenges or behaviors that lead learning to ride a bicycle; and poor processing of tactile input

to RtI services; these children may simply need additional can result in feeding difficulties due to poor awareness and

assistance but never require an FIE. localization of food in the mouth. The ASI approach is often

provided in clinical contexts to meet sensory needs such as

Section 504 these for clients receiving services funded through individual

The Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 2004, otherwise sources such as health insurance.

known as Section 504, stipulates that if an agency, such Clinic-based occupational therapists use standardized

as a school, receives federal financial assistance, it cannot assessments, skilled clinical observations, and caregiver

discriminate against a person with a disability. Discrimina- reports rather than direct peer comparison, school standards,

tion could result in revocation of the agency’s federal monies. or teacher expectations to document the child’s perfor-

There is no additional funding to agencies for 504 activities. mance. This provides therapists and families with individual

Section 504 requires school districts to provide a FAPE to performance data that can be analyzed and used to develop

students who have been determined to (1) have a physical treatment plans. Information about the child’s performance

or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more in the school context can be acquired by interviewing care-

major life activities, (2) have a record of such an impairment, givers, teachers, or other school-based personnel. In addi-

or (3) be regarded as having such an impairment. tion, clinic-based occupational therapists can use the clinic

Major life activities, as defined by Section 504, include environment and equipment to create strategic contexts that

“functions such as caring for one’s self, performing manual elicit engagement of the child in activities the therapists want

tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learn- to observe. The therapist can infer how skills and behaviors

ing, and working. This list is not exhaustive. Other functions observed in the clinic may affect the child in educational or

can be major life activities for purposes of Section 504” (34 other natural settings. A collaborative relationship between

C.F.R. 104.3(j)(2)(ii)). Children and youth with challenges the occupational therapist in the clinic and the child’s educa-

in processing and integrating sensory information who are tional occupational therapist is ideal in order to best support

not eligible for IDEA may be eligible for accommodations or the child and enhance his or her ability to generalize perfor-

modifications under this law if the impairment limits daily mance across these settings.

life activities. The school may require documentation from

a health care provider (e.g., the child’s physician) stating Private Health Insurance

the necessity of these modifications or accommodations. Private health insurance traditionally has been a major

Occupational therapists should consider using Section 504 source of funding for clinically based occupational therapy

provisions for students who require activity or environmental services in the United States. Insurance companies issue

modifications due to sensory-based needs that affect their many different policies, so coverage for services varies widely

daily life skills. and there may be restrictions based on client age, location

of service delivery, specific type of service provided, or other

Individually Funded Services factors. Occupational therapy services funded through pri-

In addition to services provided through the public school vate health insurance typically are considered medically rel-

system, children also can receive services in settings such evant and often require a physician’s referral. The physician

as outpatient clinics; hospital-affiliated programs; private referral may or may not identify the child’s diagnostic condi-

offices; their home; or other environments funded through tion and specify the frequency and duration of therapy being

private health insurance, Medicaid, accounts such as trusts prescribed. Occupational therapy practitioners can affect

or adoption support, out-of-pocket payments, or other these decisions by communicating with the referring physi-

sources. When providing services outside of the educational cian regarding the client’s occupational performance, evalu-

system, the occupational therapist can design and imple- ation results, response to intervention, and evidence in the

ment these services to address a range of needs without the literature related to the recommended strategy or duration

requirement to demonstrate an impact on educational per- of services. Observations and performance on assessments of

formance. Thus, the occupational therapy practitioner can sensory processing and integration can be especially helpful

address the neurophysiological functions that underlie sen- when considering diagnosis of a sensory processing disorder.

sory processing and integration challenges and their impact Reimbursement for occupational therapy services through

on a child’s occupational performance in home and commu- privately funded insurance is influenced by many factors.

nity contexts. For example, auditory sensitivities may cause Among these is whether a provider is recognized on the

a child to dislike or avoid noisy or crowded spaces and events company’s preferred provider register, the insurance compa-

CE-6 ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17)

Earn .1 AOTA CEU (one contact hour and 1.25 NBCOT PDU). See below for details.

ny’s approval of the specific service provided by the practi-

tioner, or the specific location in which services are provided.

Thus, the provisions of each client’s individual policy should

be reviewed carefully and any limitations that may affect How To Apply for

service delivery discussed with the child’s family prior to

beginning services. When limitations in coverage are encoun-

Continuing Education Credit

A. After reading the article Using Sensory Integration and Sensory-

tered, occupational therapy practitioners can work with Based Occupational Therapy Interventions Across Pediatric Practice

insurance companies to advocate for expanded coverage for Settings, register to take the exam online by either going to

their clients. This may include providing education of general www.aota.org/cea or calling toll-free (877) 404-2682.

occupational therapy concepts, interpreting the evidence B. Once registered you will receive your personal access informa-

in the literature related to sensory integration methods, or tion within 2 business days and can log on to www.aota-learn

ing.org to take the exam online. You will also receive a PDF

providing clinical evidence of the client’s positive response

version of the article that may be printed for personal use.

to intervention. Such negotiations can lead to extension of

C. Answer the questions to the final exam found on p. CE-8 by

services that can maximize client progress and outcomes. September 30, 2013.

D. Upon successful completion of the exam (a score of 75% or

SUMMARY more), you will immediately receive your printable certificate.

The funding sources, environments, child’s age, and frame-

work chosen for the intervention all influence occupational

therapy service delivery for children with difficulty process-

ing and integrating sensory information. Providing early

Bundy, A. C., Lane, S. J., & Murray, E. A. (2002). Sensory integration: Theory and

intervention in the home may include teaching the family practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis.

ways to feed, bathe, hold, position, or play with the child. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. Pub. L. 108-446,

Occupational therapy practitioners are in the child’s and 20 U.S.C. §1400 et seq.

family’s natural environment, so they can observe family Lane, S. J., & Schaaf, R. C. (2010). Examining the neuroscience evidence for

sensory-driven neuroplasticity: Implications for sensory-based occupational

routines and activities. In the educational setting, occupa- therapy for children and adolescents. American Journal of Occupational

tional therapy practitioners focus on the skills, environmen- Therapy, 64, 375–390. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09069

tal adaptations, and teacher supports that a child needs to No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. Pub. L. 107-110, 116 Stat. 3071.

benefit from his or her educational program. In the medical Parham, L. D., Cohn, E. S., Spitzer, S., Koomar, J. A., Miller, L. J., Burke, J. P, et

al. (2007). Fidelity in sensory integration intervention research. American

or community setting, occupational therapy pratitioners Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 216–227.

focus primarily on the child and the functional limitations Parham, L. D., Smith Roley, S., May-Benson, T. A., Koomar, J., Brett-Green, B.,

secondary to the medical condition(s). The emphasis is on Burke, J. P., et al. (2011). Development of a fidelity measure for research on

the effectiveness of the Ayres Sensory Integration® intervention. American

remediating underlying problems in the child, implementing Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65, 133–142. doi:10.5014/ajot.2011.000745

environmental adaptations, and building a broad founda- Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 2004. 29 U.S.C. §794.

tion of skills that the child can draw upon for success in Schaaf, R. C., & Davies, P. (2010a). From the desk of the guest editors: Evolution

various contexts and situations. Across all of these settings, of the sensory integration frame of reference. American Journal of Occupa-

tional Therapy, 64, 363–367.

knowledge of the brain-behavior relationships that underlie

Schaaf, R. C., & Davies, P. (Guest Eds.). (2010b). Special issue on sensory integra-

sensory processing and integration and the principles guiding tion [Special issue]. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(3).

intervention to address related deficits is an essential first Smith Roley, S., Blanche, E. I., & Schaaf, R. C. (2001). The nature of sensory inte-

step in providing relevant and effective services that promote gration with diverse populations. Tucson, AZ: Psychological Corporation.

and enhance our clients’ occupational engagement. n Smith Roley, S., Mailloux, Z., Miller Kuhaneck, H., & Glennon, T. (2007). Under-

standing Ayres Sensory Integration®. OT Practice, 12(17), CE-1–CE-8.

Tomchek, S. D., & Case-Smith, J. (2009). Occupational therapy practice guide-

REFERENCES lines for children and adolescents with autism. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press.

Ayres, A. J. (1972). Sensory integration and learning disorders. Los Angeles:

Watling, R., Bodison, S., Henry, D. A., & Miller-Kuhaneck, H. (2006, December).

Western Psychological Services.

Sensory integration: It’s not just for children. Sensory Integration Special

Ayres, A. J. (1979). Sensory integration and the child. Los Angeles: Western Interest Section Quarterly, 29(4), 1–4.

Psychological Services.

Watling, R., Koenig, K. P., Schaaf, R. C., & Davies, P. (2011). Occupational therapy

Ayres, A. J. (2005). Sensory integration and the child: Understanding hidden practice guidelines for children and adolescents with challenges in sensory

sensory challenges. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. processing and integration. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press.

SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17) ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 CE-7

Continuing Education Article 6. Practitioners can rely on the literature to consistently

and accurately identify examinations of sensory integra-

CE Article, exam, and certificate are also

available ONLINE. Register at http://www.aota. tion and sensory-based strategies.

org/cea or call toll-free 877-404-AOTA (2682). A. True B. False

7. Which aspect of the Individuals with Disabilities Educa-

Final Exam CEA0911

tion Act (IDEA) requires states to provide services to

children with disabilities?

Using Sensory Integration and Sensory-Based Occupational A. Part C (birth to 3 years)

Therapy Interventions Across Pediatric Practice Settings B. Part B (3 years to graduation)

September 26, 2011 C. Part C and Part B

D. None of the above

To receive CE credit, exam must be completed by September 30,

2013. 8. Which should be ruled out before identifying a child as

Learning Level: Entry Level having a disability under IDEA Part B?

Target Audience: Occupational therapists and occupational A. Lack of instruction in that skill area

therapy assistants B. Poor attendance at school

Content Focus: Category 2: Occupational Therapy Process: C. Limited English proficiency

D. All of the above

Evaluation; Category 3: Legal, Legislative,

Regulatory, & Reimbursement Issues

9. IDEA allows states to use up to what percent of Part B

special education money for children in general educa-

1. Sensory integration theory is based on all of the following tion who are at risk for learning and behavior challenges?

except: A. 15%

A. Psychology B. 25%

B. Human development C. 45%

C. Animal neuroscience D. 55%

D. Exercise science

10. Which civil rights statute prohibits discrimination on

2. Sensory integration intervention involves: the basis of a disability by any program receiving fed-

A. Prescribed sensory-rich activities eral funds and has been used as the basis for providing

B. Passive application of sensory experiences to the accommodations and modifications for some children

client who have a disability but are not eligible for IDEA?

C. Active engagement in a wide range of sensory-based A. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

activities B. Response to Intervention

D. Group activities in everyday environments C. Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 2004, Section 504

D. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports

3. Sensory integration intervention aims to directly address:

A. Gross motor performance deficits 11. Occupational therapy practitioners working in the clinical

B. Neurophysiological processing of sensation setting have the opportunity to:

C. Academic performance A. Observe a child’s performance during natural routines

D. Communication and activities

B. Remediate a child’s underlying deficits using a wide

4. Which of the following is true of sensory-based strategies? range of materials and equipment

A. They involve discrete sensory experiences or accom- C. Use physical space and a variety of suspended equip-

modations to support behavior ment for vigorous activities

B. They require advanced postprofessional training and D. B and C

mentoring

C. They involve monitoring the heart rate and stress 12. Occupational therapy practitioners working in home or

hormones school settings have the opportunity to:

D. They can be implemented without knowledge of sen- A. Observe and intervene with children in their natural

sory processing principles environment (e.g., bathrooms, classrooms, lunch-

rooms, playgrounds) while observing peer perfor-

5. Fidelity to sensory integration involves all of the following mance and teacher/family expectations

except: B. Observe and evaluate the environmental supports

A. Practitioner training and barriers that are present during the child’s

B. Environmental affordances performance

C. Process elements C. Facilitate the child’s performance in daily occupations

D. Consistency with the International Classification of by collaborating with the teacher

Function D. All of the above

CE-8 ARTICLE CODE CEA0911 SEPTEMBER 2011 n OT PRACTICE, 16(17)

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- A Field Guide to Sensory Motor Integration: The Foundation for LearningFrom EverandA Field Guide to Sensory Motor Integration: The Foundation for LearningNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy Sensory Integration Protocol For Early InterDocument56 pagesOccupational Therapy Sensory Integration Protocol For Early Intermanali vyasNo ratings yet

- Neural Foundations of Ayres Sensory Integration®Document15 pagesNeural Foundations of Ayres Sensory Integration®Muskaan KhannaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Pediatric Assessment Tools For Sensory Integration AOTADocument3 pagesA Review of Pediatric Assessment Tools For Sensory Integration AOTAhelenzhang888No ratings yet

- OT For AutismDocument2 pagesOT For AutismArianna Apreutesei3152eri8oawiNo ratings yet

- The Effect of A Two-Week Sensory Diet On Fussy Infants With Regulatory SensDocument8 pagesThe Effect of A Two-Week Sensory Diet On Fussy Infants With Regulatory Sensapi-238703581No ratings yet

- An Integrated Approach - in Every SenseDocument4 pagesAn Integrated Approach - in Every SenseSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Marcus Evaluation - StruthersDocument8 pagesMarcus Evaluation - Struthersapi-355500890No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Sensory Integration Therapy For Children With AutismDocument16 pagesThe Effectiveness of Sensory Integration Therapy For Children With Autismapi-382628487No ratings yet

- Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral PalsyDocument11 pagesEarly, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral PalsyRoberto López MataNo ratings yet

- Ot GuidelinesDocument107 pagesOt GuidelinesAhmed MaherNo ratings yet

- Sensory Integration PDFDocument1 pageSensory Integration PDFmofasorgNo ratings yet

- Ayres Sensory Integration PrinciplesDocument25 pagesAyres Sensory Integration Principlesapi-413184352100% (2)

- Handwriting PortfolioDocument8 pagesHandwriting Portfolioapi-254940946No ratings yet

- The Fundamental Principles of Seating and Positioning in Children and Young People With Physical DisabilitiesDocument54 pagesThe Fundamental Principles of Seating and Positioning in Children and Young People With Physical DisabilitiesKiran Dama100% (1)

- AUT - Unit3.4 Sensory Self-RegulationDocument31 pagesAUT - Unit3.4 Sensory Self-RegulationMai Mahmoud100% (1)

- NATURE Is The ULTIMATE SENSORY EXPERIENCE: A Pediatric Occupational Therapist Makes The Case For Nature Therapy: The New Nature MovementDocument5 pagesNATURE Is The ULTIMATE SENSORY EXPERIENCE: A Pediatric Occupational Therapist Makes The Case For Nature Therapy: The New Nature MovementSimonetta MangioneNo ratings yet

- Sensory Regulation ConferenceDocument19 pagesSensory Regulation ConferenceSebastian Pinto ReyesNo ratings yet

- 11 17 17 Treatment PlanDocument7 pages11 17 17 Treatment Planapi-435469413No ratings yet

- Kathryn Edmands The Impact of Sensory ProcessingDocument26 pagesKathryn Edmands The Impact of Sensory ProcessingBojana VulasNo ratings yet

- Sensory Integration and Praxis Patterns in Children With AutismDocument9 pagesSensory Integration and Praxis Patterns in Children With AutismadriricaldeNo ratings yet

- Understanding sensory processing and integration problemsDocument4 pagesUnderstanding sensory processing and integration problemsmaria teresa caba gallegoNo ratings yet

- Early Stimulation and Development ActivitiesDocument63 pagesEarly Stimulation and Development ActivitiesRucsandra AvirvareiNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapists Prefer Combining PDFDocument12 pagesOccupational Therapists Prefer Combining PDFSuperfixenNo ratings yet

- Supporting Therapy in The Classroom Strategies For OccupationalDocument70 pagesSupporting Therapy in The Classroom Strategies For Occupationalapi-451269263No ratings yet

- PD Sensory Room TrainingDocument35 pagesPD Sensory Room Trainingapi-393264699No ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Paediatric Occupational Therapy For Chidren With Disabilities A Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesEffectiveness of Paediatric Occupational Therapy For Chidren With Disabilities A Systematic ReviewCynthia RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Topss Poster PDFDocument1 pageTopss Poster PDFUNNo ratings yet

- Sensory Processing Booklet For ParentsDocument5 pagesSensory Processing Booklet For Parentsamrut muzumdar100% (1)

- Create No-Stress Sensory Diet KidsDocument4 pagesCreate No-Stress Sensory Diet KidsAdriana NegrescuNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Sensory Integration Therapy On Children With Asperger's Syndrome and Pdd-NosDocument278 pagesThe Efficacy of Sensory Integration Therapy On Children With Asperger's Syndrome and Pdd-NosAbu FayyadhNo ratings yet

- Making Sense Out of Sensory Processing Disorder: Kay Kopp, OTR/L Tanyia Schier, MS, OTR/LDocument61 pagesMaking Sense Out of Sensory Processing Disorder: Kay Kopp, OTR/L Tanyia Schier, MS, OTR/LKriti Shukla100% (1)

- Integrating ReflexesDocument2 pagesIntegrating ReflexesAna G. VelascoNo ratings yet

- Where To Begin and Where To GoDocument25 pagesWhere To Begin and Where To GoLaurine Manana100% (1)

- Clinical Observations of Sensory IntegrationDocument2 pagesClinical Observations of Sensory IntegrationIsti Nisa100% (1)

- Occupational Performance CoachingDocument8 pagesOccupational Performance CoachingEtneciv ParedesNo ratings yet

- Dir - Floortime Model - Using Relationship-Based Intervention To IncDocument33 pagesDir - Floortime Model - Using Relationship-Based Intervention To IncAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Supporting Children To Participate Successfully in Everyday Life Using Sensory Processing KnowledgeDocument19 pagesSupporting Children To Participate Successfully in Everyday Life Using Sensory Processing Knowledgeapi-26018051100% (1)

- Sensory DietDocument4 pagesSensory Dietapi-571361183No ratings yet

- DIR® Assessment: Diane Cullinane, M.D. ICDL Southern California DIR®/Floortime™ Regional Institute 2009-2010Document42 pagesDIR® Assessment: Diane Cullinane, M.D. ICDL Southern California DIR®/Floortime™ Regional Institute 2009-2010circlestretch100% (1)

- Floortime in Schools and Home. Formal Floortime and Floortime Philosophy in All InteractionsDocument7 pagesFloortime in Schools and Home. Formal Floortime and Floortime Philosophy in All InteractionsLeonardo VidalNo ratings yet

- Building Bridges Through Sensory Integration: Therapy For Children With Autism and Other Pervasive Developmental Disorders - Child & Developmental PsychologyDocument4 pagesBuilding Bridges Through Sensory Integration: Therapy For Children With Autism and Other Pervasive Developmental Disorders - Child & Developmental Psychologywureleli0% (2)

- Helping Hands-Website InformationDocument17 pagesHelping Hands-Website InformationDiana Moore Díaz100% (1)

- 132 Sensory Diet 090212Document2 pages132 Sensory Diet 090212Sally Vesper100% (1)

- Developmental Milestones Motor Development - Peds Rev 2010Document13 pagesDevelopmental Milestones Motor Development - Peds Rev 2010Carolina SanchezNo ratings yet

- Sensory Motor IntegrationDocument8 pagesSensory Motor IntegrationAdelinaPanaetNo ratings yet

- SPM IntroduccionDocument20 pagesSPM IntroduccionConstanzaNo ratings yet

- Sensory Integration Therapy for Developmental DelaysDocument2 pagesSensory Integration Therapy for Developmental DelaysPie YnawatNo ratings yet

- ASD Document PDFDocument334 pagesASD Document PDFDiana RuicanNo ratings yet

- Developmental Assessment, Warning Signs and Referral PathwaysDocument33 pagesDevelopmental Assessment, Warning Signs and Referral PathwaysJonathan TayNo ratings yet

- AOTA Statement On Role of OT in NICUDocument9 pagesAOTA Statement On Role of OT in NICUMapi RuizNo ratings yet

- TACTILE AND PROPRIOCEPTIVE INTERVENTIONDocument13 pagesTACTILE AND PROPRIOCEPTIVE INTERVENTIONAnup Pednekar100% (1)

- Enhanced Milieu Teaching BrochureDocument3 pagesEnhanced Milieu Teaching Brochureapi-458332874No ratings yet

- Sensory History QuestionnaireDocument6 pagesSensory History Questionnaireİpek OMUR100% (1)

- Sensory Integration Theory - InserviceDocument10 pagesSensory Integration Theory - Inserviceapi-238703581No ratings yet

- Ota Watertown Si Clinical Assessment WorksheetDocument4 pagesOta Watertown Si Clinical Assessment WorksheetPaulinaNo ratings yet

- Eating Difficulties in Children and Young People With DisabilitiesDocument32 pagesEating Difficulties in Children and Young People With DisabilitiesWasim KakrooNo ratings yet

- Books Sensory IntegrationDocument4 pagesBooks Sensory IntegrationRabe Allah100% (1)

- Sensory Integrative TechniquesDocument21 pagesSensory Integrative TechniquesVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Banner Day Cake TopperDocument5 pagesBanner Day Cake TopperVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Child-Report Measures of Occup PDFDocument25 pagesChild-Report Measures of Occup PDFVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Children's Hand Skills Framework DevelopmentDocument1 pageChildren's Hand Skills Framework DevelopmentVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Clay in The Montessori ClassroDocument9 pagesClay in The Montessori ClassroVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Fine Motor SkillsDocument94 pagesKindergarten Fine Motor SkillsVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Outcomes FromDocument5 pagesOutcomes FromVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Afrikaans Stomp I SummaryDocument1 pageAfrikaans Stomp I SummaryVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Fine Motor SkillsDocument94 pagesKindergarten Fine Motor SkillsVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Sensitivity of TDocument10 pagesAssessing The Sensitivity of TVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Apple ActivitiesDocument20 pagesApple ActivitiesVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Sensitivity of TDocument10 pagesAssessing The Sensitivity of TVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Communication For Students With DisabilitiesDocument5 pagesFacilitating Communication For Students With DisabilitiesVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy Using A SensoryDocument6 pagesOccupational Therapy Using A SensoryVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- OregonDocument20 pagesOregonVero MoldovanNo ratings yet

- The Zone Issue 27Document16 pagesThe Zone Issue 27Jeff Clay GarciaNo ratings yet

- Personal Development ReviewerDocument3 pagesPersonal Development ReviewerHwannies SoNo ratings yet

- Raise Organic HogsDocument122 pagesRaise Organic HogsDanny R. Salvador100% (2)

- (ILM Super Series) Institute of Leadership & Mana - Caring For The Customer Super Series, Fourth Edition - Pergamon Flexible Learning (2002)Document117 pages(ILM Super Series) Institute of Leadership & Mana - Caring For The Customer Super Series, Fourth Edition - Pergamon Flexible Learning (2002)bankadhi100% (1)

- Central Causes of DizzinessDocument9 pagesCentral Causes of DizzinessGLORIA MEDINA HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- ABYIP-2023 TemplateDocument3 pagesABYIP-2023 Templatejomar88% (26)

- Blue Plains Plant Brochure PDFDocument7 pagesBlue Plains Plant Brochure PDFAfzal AhmadNo ratings yet

- Navigating The Labyrinth of Love 2013cDocument15 pagesNavigating The Labyrinth of Love 2013cvictoriaNo ratings yet

- Social Work ResearchDocument15 pagesSocial Work ResearchSuresh Murugan78% (9)

- Failure To ThriveDocument3 pagesFailure To Thriveibbs91No ratings yet

- Positioning and Drafting ReviewerDocument4 pagesPositioning and Drafting ReviewerKathrina Mendoza HembradorNo ratings yet

- Phase III CT in Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument13 pagesPhase III CT in Alzheimer's DiseaseKlesta Durović100% (1)

- Strategies For Minimizing Dispensing ErrorsDocument3 pagesStrategies For Minimizing Dispensing ErrorsAnah MayNo ratings yet

- Infant Formula and Early Childhood CariesDocument5 pagesInfant Formula and Early Childhood Cariesmutiara hapkaNo ratings yet

- DM-PH&SD-GU17-HCKS2 - Health Requirements For Kids SalonsDocument13 pagesDM-PH&SD-GU17-HCKS2 - Health Requirements For Kids SalonsPraveenKatkooriNo ratings yet

- ISCO-08 Part 4: Correspondence TablesDocument75 pagesISCO-08 Part 4: Correspondence TableslivelongerNo ratings yet

- Module Four Wellness PlanDocument12 pagesModule Four Wellness Plankayle mylerNo ratings yet

- Temporary Nursing Staff - Cost and Quality Issues: OriginalresearchDocument10 pagesTemporary Nursing Staff - Cost and Quality Issues: OriginalresearchRobert CoffinNo ratings yet

- HPTLC Fingerprinting Analysis of Evolvulus Alsinoides (L.) LDocument6 pagesHPTLC Fingerprinting Analysis of Evolvulus Alsinoides (L.) LNishadh NishNo ratings yet

- Thesis PPT For VivaDocument62 pagesThesis PPT For VivaNamrata DahakeNo ratings yet

- Two Factor Theory Motivation-Hygiene Theory: Dual-Factor Theory/ Theory of Work Behavior byDocument16 pagesTwo Factor Theory Motivation-Hygiene Theory: Dual-Factor Theory/ Theory of Work Behavior byAngha0% (1)

- Animal Bite/Scratch: Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesAnimal Bite/Scratch: Page 1 of 2Sherwin Michael MacatangayNo ratings yet

- Abnoramal ECGDocument20 pagesAbnoramal ECGImmanuelNo ratings yet

- Sr. Company Name First Name Last Name TitleDocument3 pagesSr. Company Name First Name Last Name Titleakash.shahNo ratings yet

- Flow RateDocument2 pagesFlow Rateفيرمان ريشادNo ratings yet

- Abc of Burns: Kanwal Khan Lecturer ZCPTDocument35 pagesAbc of Burns: Kanwal Khan Lecturer ZCPTKanwal KhanNo ratings yet

- Project SarvodayaDocument21 pagesProject SarvodayaArun Kumar PNo ratings yet

- Optima Restore Rate Card Inclusive of Service TaxDocument2 pagesOptima Restore Rate Card Inclusive of Service Taxmksnake77No ratings yet

- Parent Perspectives of Their Involvement in IEP Development For Children With AutismDocument11 pagesParent Perspectives of Their Involvement in IEP Development For Children With AutismGiselle ProvencioNo ratings yet

- Soccer Class-Action Complaint - Aug. 27, 2014Document138 pagesSoccer Class-Action Complaint - Aug. 27, 2014Evan Buxbaum, CircaNo ratings yet

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (78)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (402)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingFrom EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- CBT Strategies: CBT Strategies for Overcoming Panic, Fear, Depression, Anxiety, Worry, and AngerFrom EverandCBT Strategies: CBT Strategies for Overcoming Panic, Fear, Depression, Anxiety, Worry, and AngerNo ratings yet

- Summary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: How to Be an Adult in Relationships: The Five Keys to Mindful Loving by David Richo: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Summary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: Thinking, Fast and Slow: by Daniel Kahneman: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (61)

- Daniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisFrom EverandDaniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow": A Macat AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (130)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossFrom EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsFrom EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsNo ratings yet

- The Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeFrom EverandThe Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeNo ratings yet