Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Love Yourself Louise Hay

Uploaded by

Cleofe Lagura Diaz0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

237 views12 pagesDepression

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDepression

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

237 views12 pagesLove Yourself Louise Hay

Uploaded by

Cleofe Lagura DiazDepression

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

© Copyright, Princeton University Press.

No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

INTRODUCTION

Recent experiments have shown that psilo-

cybin, a compound found in hallucinogenic

mushrooms, can greatly reduce the fear of

death in terminal cancer patients. The drug

imparts “an understanding that in the larg-

est frame, everything is fine,” said pharma-

cologist Richard Griffiths in a 2016 inter-

view.1 Test subjects reported a sense of “the

interconnectedness of all people and things,

the awareness that we are all in this to-

gether.” Some claimed to have undergone a

mock death during their psychedelic expe-

rience, to have “stared directly at death . . .

in a kind of dress rehearsal,” as Michael

Pollan wrote in a New Yorker account of

ix

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

these experiments.2 The encounter was felt

to be not morbid or terrifying, but liberat-

ing and affirmative.

“In the largest frame, everything is fine.”

That sounds very much like the message

Lucius Annaeus Seneca preached to Roman

readers of the mid-first century AD, rely-

ing on Stoic philosophy, rather than an or-

ganic hallucinogen, as a way to glimpse that

truth. “The interconnectedness of all things”

was also one of his principal themes, as was

the idea that one must rehearse for death

throughout one’s life—for life, properly un-

derstood, is really only a journey toward

death; we are dying every day, from the day

we are born. In the passages collected here,

excerpted from eight different works of

ethical thought, Seneca spoke to his ad-

dressees, and through them to humankind

generally, about the need to accept death,

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

even to the point of ending one’s own life,

with a candor nearly unparalleled in his

time or ours.

“Study death always,” Seneca counseled

his friend Lucilius, and he took his own ad-

vice. From what is likely his earliest work,

the Consolation to Marcia (written around

AD 40), to the magnum opus of his last

years (63–65), the Moral Epistles, Seneca

returned again and again to this theme. It

crops up in the midst of unrelated discus-

sions, as though never far from his mind;

a ringing endorsement of rational suicide,

for example, intrudes without warning

into advice about keeping one’s temper, in

On Anger. Examined together, as they are

in this volume, Seneca’s thoughts organize

themselves around a few key themes: the

universality of death; its importance as life’s

final and most defining rite of passage; its

xi

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

part in purely natural cycles and processes;

and its ability to liberate us, by freeing souls

from bodies or, in the case of suicide, to give

us an escape from pain, from the degrada-

tion of enslavement, or from cruel kings

and tyrants who might otherwise destroy

our moral integrity.

This last point had particular resonance

for Seneca and his original readers, who had

often seen death or degradation arrive at an

emperor’s behest. A politician as well as a

philosopher, Seneca had been a young sen-

ator in the late 30s AD, when Caligula went

mad and began brutalizing those he mis-

trusted; in the 40s, under Claudius, Seneca

was himself sentenced to death in a political

show trial, but the sentence was commuted

to exile on the island of Corsica. Recalled to

Rome and appointed tutor to young Nero,

Seneca spent the 50s and early 60s inside

xii

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

the imperial household, watching as Nero

became more deranged and, toward family

members whom he perceived as threats,

murderous. Finally, suspected (probably

wrongly) of collusion in a failed assassina-

tion plot, Seneca too incurred Nero’s wrath

and was forced to commit suicide himself,

in his sixties, in AD 65.

Rome’s century-old form of government,

in which a princeps or “first man” held un-

official but near-absolute power, had, in the

reign of Caligula especially, revealed itself

as an autocracy. As chief adviser to Nero

for more than a decade, Seneca dutifully

served the system’s needs, and got rich by

doing so, points held against him by his

contemporaries (and by modern readers as

well). But philosophy offered an antidote

to the toxic atmosphere of the imperial pal-

ace. Seneca continued to publish treatises

xiii

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

throughout his fifteen years at Nero’s side,

giving friends and fellow senators a larger

moral framework for dealing with troubled

times. (He wrote verse tragedies as well, of

which many survive today, though these

works, vastly different in tone from his

prose writings, are not included in this

volume.)

Seneca, like many leading Romans of his

day, found that larger moral framework in

Stoicism, a Greek school of thought that

had been imported to Rome in the preced-

ing century and had begun to flourish there.

The Stoics taught their followers to seek an

inner kingdom, the kingdom of the mind,

where adherence to virtue and contempla-

tion of nature could bring happiness even

to an abused slave, an impoverished exile, or

a prisoner on the rack. Wealth and position

were regarded by the Stoics as adiaphora,

xiv

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

“indifferents,” conducing neither to happi-

ness nor to its opposite. Freedom and health

were desirable only in that they allowed one

to keep one’s thoughts and ethical choices

in harmony with Logos, the divine Reason

that, in the Stoic view, ruled the cosmos

and gave rise to all true happiness. If free-

dom were destroyed by a tyrant or health

were forever compromised, such that the

promptings of Reason could no longer be

obeyed, then death might be preferable to

life, and suicide, or self-euthanasia, might

be justified.

Seneca inherited this Stoic system from

his Greek predecessors and his Roman

teachers, but gave new prominence to its

doctrines concerning modes of death and,

in particular, suicide. Indeed this last topic

receives an emphasis in his writings that far

exceeds what is found in other surviving

xv

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

Stoic treatises, such as the Discourses of

Epictetus or the Meditations of Marcus Au-

relius. We modern readers must bear in

mind that, as a political insider under two

of Rome’s most depraved rulers, Seneca

often witnessed suicides of the kind he de-

scribes in his essays. Caligula and Nero,

and indeed all the Julio-Claudian emperors,

regularly required their political enemies to

take their own lives, threatening to both

execute them and seize their estates, if they

did not do so. Seneca was a witness to many

such forced suicides, and so he revisits the

theme of whether and when to make an exit

from pain, or from political oppression,

with a frequency and intensity that go far

beyond his fellow Stoics.

In other ways too, Seneca was more than

a pure or doctrinaire follower of the Stoic

path. At times he borrows from the Epicu-

xvi

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

reans, a rival school, the idea that death is

merely a dissolution into constituent ele-

ments that will have a new “life” as parts of

other substances. Occasionally he sounds

the Platonic theme of the immortality and

infinite reincarnations of the human soul.

He had no fixed ideas about the afterlife,

except for his certainty that it held nothing

fearful, and that the visions of monsters

and torments in Hades promulgated by the

poets were only empty fictions. He wavered

too in his assessments of self-euthanasia:

at times he praises those who forestalled a

painful death, or an execution, by ending

their own lives, but at others he admires the

fortitude of those who declined to do this.

Even in the case of suicide, which he gen-

erally defends as preferable to a morally

debased life, Seneca reveals one hesitation:

when family and friends depend on you, he

xvii

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

admits in one passage of his Epistles, you

may have to pull your departing life back

from the brink. (He himself, as a young man

plagued by suffocating respiratory illness,

had rejected suicide for the sake of his el-

derly father, or so he tells us in Epistle 78.1,

a passage not included in this volume.)

The “right to die,” even in cases of pain-

ful terminal illness, has proven a conten-

tious idea for modern societies. Physician-

assisted suicide or voluntary euthanasia has

been legalized, at the time of this writing,

by only a handful of countries and by four

out of fifty US states; in nearly all cases, the

laws permitting these measures have been

passed only within the last two decades.

Debate over these legal measures has usu-

ally been intense, with opponents often bas-

ing their arguments on notions of the sanc-

tity of human life. But Seneca’s writings

xvii i

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

remind us that there is also such a thing as a

sanctity of death. To “die well” was im-

mensely important to Seneca, whether that

meant accepting one’s death with equanim-

ity, choosing the time or method of one’s

exit, or, as he often illustrates with vivid ex-

amples, enduring with courage the violence

done to one’s body, either by one’s own

hand or by that of an implacable enemy.

Because these examples are so frequent

and so grim, modern readers have some-

times found Seneca’s writings to be macabre

or death obsessed. But Seneca might reply

that such readers are life obsessed, deluding

themselves with a denial of the importance

of death. Dying, for him, was one of the

essential functions of living, and the only

one that could not be learned or refined

through repetition. Because we will die only

once, and quite possibly without advance

xix

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be

distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical

means without prior written permission of the publisher.

I ntroduction

warning, it’s essential that we prepare our-

selves ahead of time and be ready at all

moments.

“Study death,” “rehearse for death,”

“practice death”—this constant refrain in

his writings did not, in Seneca’s eyes, spring

from a morbid fixation but rather from a

recognition of how much was at stake in

navigating this essential, and final, rite of

passage. “A whole lifetime is needed to

learn how to live, and—perhaps you’ll find

this more surprising—a whole lifetime is

needed to learn how to die,” he wrote in

On the Shortness of Life (7.3). The passages

collected in this volume—chosen from the

eight prose treatises in which death looms

largest, spanning about a quarter century of

Seneca’s life—are his attempts to accelerate

that lesson.

xx

For general queries, contact webmaster@press.princeton.edu

You might also like

- Spinal Emotional Associations Louise HayDocument3 pagesSpinal Emotional Associations Louise Hayklm3zph97% (58)

- You Can Heal Your Life (Louise L. Hay)Document24 pagesYou Can Heal Your Life (Louise L. Hay)Diyana Tahir93% (123)

- Heal Your Body - Louise HayDocument4 pagesHeal Your Body - Louise Haybunefobo16% (25)

- Love Yourself Louise Hay PDFDocument1 pageLove Yourself Louise Hay PDFCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Love Yourself Louise Hay PDFDocument1 pageLove Yourself Louise Hay PDFCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Love Yourself Louise Hay PDFDocument1 pageLove Yourself Louise Hay PDFCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- 101 Power Thoughts For Life From Louise HayDocument13 pages101 Power Thoughts For Life From Louise HayFufen Zuo100% (4)

- Affirmations of Louise HayDocument18 pagesAffirmations of Louise HayV Ranga NathanNo ratings yet

- Emotional sources of common diseasesDocument1 pageEmotional sources of common diseasesWhisperer Bowen100% (17)

- AFFIRMATIONS of LOUISE HAYDocument18 pagesAFFIRMATIONS of LOUISE HAYVRnlp91% (32)

- Natural LawDocument12 pagesNatural LawLAW MANTRA100% (2)

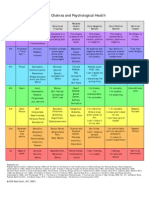

- Chakra HandoutDocument2 pagesChakra Handoutmecardxviii100% (10)

- Wind HUME AND THE HEROIC PORTRAIT PDFDocument55 pagesWind HUME AND THE HEROIC PORTRAIT PDFzac l.100% (1)

- Louise Hay Thought FormsDocument15 pagesLouise Hay Thought Formsjanglepuss100% (15)

- Louise HayDocument29 pagesLouise Haymihaela irofte100% (2)

- I Can Doit - Wealth - by Louise HayDocument28 pagesI Can Doit - Wealth - by Louise Haykiranbabud100% (9)

- Discover How Your Thoughts Can Heal Your LifeDocument8 pagesDiscover How Your Thoughts Can Heal Your LifeKrishnakumar Menon88% (8)

- 101 Best Louise Hay AffirmationsDocument21 pages101 Best Louise Hay AffirmationsOana Muntean100% (5)

- Heal Your BodyDocument54 pagesHeal Your BodyMaiden Di100% (12)

- Healing CodesDocument3 pagesHealing CodesZEBADEEE85% (13)

- Remove Limiting Beliefs v2Document10 pagesRemove Limiting Beliefs v2alexburkee100% (6)

- Abraham Hicks Anew Beginning 2Document214 pagesAbraham Hicks Anew Beginning 2Stefan Jackson100% (5)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Neom Happiness Ebook PDFDocument19 pagesNeom Happiness Ebook PDFCleofe Lagura Diaz100% (1)

- How IWrote TOITWDocument9 pagesHow IWrote TOITWDumitru Mihai88% (16)

- La Puissance de L'intelligibleDocument282 pagesLa Puissance de L'intelligibleJuan José Fuentes Ubilla100% (1)

- Louise Hay ThoughtsDocument62 pagesLouise Hay Thoughtsgalusca2001100% (4)

- ICANDOIT HEALTHbyLouiseHayDocument28 pagesICANDOIT HEALTHbyLouiseHayJovana Ognenovska Bakalovska100% (6)

- Icandoit Wealth BylouisehayDocument28 pagesIcandoit Wealth Bylouisehaywolfgangl70100% (12)

- Hay House World Summit 2017ebook Final - pdf-1492456039Document47 pagesHay House World Summit 2017ebook Final - pdf-1492456039270573100% (2)

- Let Go of ControlDocument5 pagesLet Go of ControlFilipe Rovarotto100% (2)

- Louise L Hay PhilosophyDocument1 pageLouise L Hay PhilosophyV Ranga Nathan100% (1)

- Power AffirmationsDocument154 pagesPower Affirmationsmilly790% (10)

- ICANDOIT Selfesteem ByLouiseHay PDFDocument28 pagesICANDOIT Selfesteem ByLouiseHay PDFRoman TilahunNo ratings yet

- You Can Heal Your LifeDocument59 pagesYou Can Heal Your Lifeljmbasecc100% (4)

- Affirmations & ReprogrammingDocument24 pagesAffirmations & ReprogrammingVERITYjnanaZETETIC100% (7)

- The Power of LoveDocument179 pagesThe Power of Lovebobsherif94% (16)

- Abundance Releasing Limiting BeliefsDocument21 pagesAbundance Releasing Limiting BeliefsKonkman100% (11)

- ICANDOIT STRESSFREE byLouiseHayDocument28 pagesICANDOIT STRESSFREE byLouiseHayBrinda Dasha100% (2)

- Abraham-Hicks Journal Vol 36 - 2006.2QDocument64 pagesAbraham-Hicks Journal Vol 36 - 2006.2QtheherbsmithNo ratings yet

- Chakras and HealtDocument1 pageChakras and Healtaurorascribid100% (5)

- 22 Louise Hay - The List - Affirmations FilteredDocument15 pages22 Louise Hay - The List - Affirmations Filteredch srinivas100% (2)

- You Can Heal Your LifeDocument11 pagesYou Can Heal Your LifePrateek JhanjiNo ratings yet

- Lindsay Kenny Procrastination TranscriptDocument16 pagesLindsay Kenny Procrastination TranscriptDilek E100% (1)

- Making peace with our bodiesDocument9 pagesMaking peace with our bodiesjack blackNo ratings yet

- Clearing Limiting BeliefsDocument25 pagesClearing Limiting BeliefsAngelshell3490% (10)

- Guide to Increasing Your Energetic FrequencyDocument11 pagesGuide to Increasing Your Energetic Frequencymuitasorte970% (10)

- Self Love SecretsDocument20 pagesSelf Love Secretsavinash008jha6735100% (1)

- The 7 Secrets of Energy Medicine: How The Healing Code WorksDocument9 pagesThe 7 Secrets of Energy Medicine: How The Healing Code WorksJed Diamond100% (15)

- Phobias ResourcesDocument14 pagesPhobias Resourcesgeoghomewood100% (2)

- FLOURISH: Democracy or Hypocrisy: Democracy or Hypocrisy: BOOK II of the TRILOGY Renaissance: Healing The Great DivideFrom EverandFLOURISH: Democracy or Hypocrisy: Democracy or Hypocrisy: BOOK II of the TRILOGY Renaissance: Healing The Great DivideNo ratings yet

- On the Nature of Things (Translated by William Ellery Leonard with an Introduction by Cyril Bailey)From EverandOn the Nature of Things (Translated by William Ellery Leonard with an Introduction by Cyril Bailey)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (368)

- 0000Document7 pages0000woo woo wongNo ratings yet

- Robert Anton Wilson - Is Capitalism A Revealed ReligionDocument11 pagesRobert Anton Wilson - Is Capitalism A Revealed Religion_mryuk_No ratings yet

- Creation in 6 Days DebunkedDocument27 pagesCreation in 6 Days DebunkedRonald WederfoortNo ratings yet

- Noyes - Seneca On DeathDocument18 pagesNoyes - Seneca On DeathEduardo SierraNo ratings yet

- PERIODSDocument5 pagesPERIODSsevincyavuz2222No ratings yet

- J.Strauss - State of DeathDocument10 pagesJ.Strauss - State of DeathnatychukNo ratings yet

- 0201 Aron GB 2Document18 pages0201 Aron GB 2Anahi GimenezNo ratings yet

- Philosophy in Turbulent Times: Canguilhem, Sartre, Foucault, Althusser, Deleuze, DerridaFrom EverandPhilosophy in Turbulent Times: Canguilhem, Sartre, Foucault, Althusser, Deleuze, DerridaNo ratings yet

- Suicide in America:: Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument6 pagesSuicide in America:: Frequently Asked QuestionsCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- 2802 3498Document3 pages2802 3498Cleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- ENG PCIPolicyFrameworkDocument28 pagesENG PCIPolicyFrameworkAdria Putra FarhandikaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Substances & Their Uses PDFDocument92 pagesUnderstanding Substances & Their Uses PDFmajdNo ratings yet

- Understanding SuicideDocument2 pagesUnderstanding Suicideapi-355166390No ratings yet

- Know The Facts About DrugsDocument20 pagesKnow The Facts About DrugszipzapdhoomNo ratings yet

- 1109 1176 PDFDocument68 pages1109 1176 PDFCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- TR 228 PDFDocument234 pagesTR 228 PDFCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Ten keys to happier living: Build strong relationships, be active, keep learningDocument28 pagesTen keys to happier living: Build strong relationships, be active, keep learningferranuk100% (2)

- SuicideDocument6 pagesSuicideZildian Gem SosaNo ratings yet

- 7 Ways PDFDocument5 pages7 Ways PDFCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Recovering KeysDocument28 pagesRecovering KeysCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- 20 Simple Tips To Be Happy Now PDFDocument11 pages20 Simple Tips To Be Happy Now PDFLaura OtiNo ratings yet

- Suicide PDFDocument184 pagesSuicide PDFWilbert Barzola HuamanNo ratings yet

- Howtobehappyeveryday LWC PDFDocument12 pagesHowtobehappyeveryday LWC PDFCleofe Lagura Diaz100% (1)

- Annual Review 2016Document26 pagesAnnual Review 2016Cleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Depression Developing Plan To OvercometDocument13 pagesDepression Developing Plan To OvercometCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Annual Review 2016Document26 pagesAnnual Review 2016Cleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Apa Style Sample PaperDocument12 pagesApa Style Sample Paperjoerunner407No ratings yet

- Love Yourself Louise HayDocument1 pageLove Yourself Louise HayCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Annual Review 2016Document26 pagesAnnual Review 2016Cleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Love Yourself Louise HayDocument1 pageLove Yourself Louise HayCleofe Lagura DiazNo ratings yet

- Coping With DepressionDocument39 pagesCoping With DepressionaldiNo ratings yet

- How To Write An Effective Research ReportDocument33 pagesHow To Write An Effective Research Reportharshalp1212No ratings yet

- An Overview of Natural Law # Jonathan DolhentyDocument5 pagesAn Overview of Natural Law # Jonathan DolhentyArkanudDin YasinNo ratings yet

- Paul in His Hellenistic ContextDocument372 pagesPaul in His Hellenistic Contextfortuna heraNo ratings yet

- Stoic Virtues. Chrysippus and The Theological Foundations of Stoic Ethics - JedanDocument243 pagesStoic Virtues. Chrysippus and The Theological Foundations of Stoic Ethics - Jedannb2013100% (2)

- A Short History of Medical EthicsDocument168 pagesA Short History of Medical EthicsIvana GreguricNo ratings yet

- Stoic Notes SpreadsDocument107 pagesStoic Notes SpreadsLeidyAcostaNo ratings yet

- Quotes From SenecaDocument4 pagesQuotes From Senecaapi-299513272No ratings yet

- The Contributions of Greco-Roman and Jewish Cultures to Early ChristianityDocument11 pagesThe Contributions of Greco-Roman and Jewish Cultures to Early ChristianityCj Mustang12No ratings yet

- Immortality in Ancient PhilosophyDocument7 pagesImmortality in Ancient PhilosophyYasin Md RafeeNo ratings yet

- Virtue and Art: Exploring Connections Between Morality and Visual CultureDocument19 pagesVirtue and Art: Exploring Connections Between Morality and Visual CultureIldikó SzentpéterinéNo ratings yet

- 1-Sentence-Summary: The Obstacle Is The Way Is A Modern Take On The Ancient PhilosophyDocument4 pages1-Sentence-Summary: The Obstacle Is The Way Is A Modern Take On The Ancient PhilosophyPriyashree RoyNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Thesis IntroductionDocument13 pagesHow To Write A Thesis IntroductionBen CungteNo ratings yet

- Stoic Epistemic VirtuesDocument20 pagesStoic Epistemic VirtuesDani PinoNo ratings yet

- Turn Anxiety Into AdvantageDocument26 pagesTurn Anxiety Into AdvantageIgnacio Andrés Torres NeiraNo ratings yet

- 4 Natural Law EthicsDocument25 pages4 Natural Law EthicsJason GeraldeNo ratings yet

- Module 4 The Epicurean and Stoicism EthicsDocument22 pagesModule 4 The Epicurean and Stoicism EthicsRHEA BABLESNo ratings yet

- Alejandro de Acosta How To Live Now or Never Essays and Experiments 20052013 PDFDocument286 pagesAlejandro de Acosta How To Live Now or Never Essays and Experiments 20052013 PDFallahNo ratings yet

- Jesus as an Ethical and Religious TeacherDocument13 pagesJesus as an Ethical and Religious TeacheronisimlehaciNo ratings yet

- Influence of Greek Ideas and Usages On Church, Edwin Hatch. 1890Document392 pagesInfluence of Greek Ideas and Usages On Church, Edwin Hatch. 1890David Bailey100% (2)

- Zeno Clean The Spears OnDocument368 pagesZeno Clean The Spears OnumitNo ratings yet

- Virtue and Law in Plato and Beyond - Sanet.cdDocument243 pagesVirtue and Law in Plato and Beyond - Sanet.cdestrago100% (3)

- Revue Internationale de PhilosophieDocument20 pagesRevue Internationale de PhilosophiePedro Thyago Santos FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Human Dignity and Bioethics PDFDocument577 pagesHuman Dignity and Bioethics PDFskilmag100% (1)

- Modern Stoicism and The ResponsibilDocument9 pagesModern Stoicism and The Responsibilyixuan.chew.2023No ratings yet

- ''ქრისტიანობის კვლევები'' # I Christian Researches # 1Document163 pages''ქრისტიანობის კვლევები'' # I Christian Researches # 1Misha KartvelishviliNo ratings yet

- Tarnas-Passion of The Western MindbDocument72 pagesTarnas-Passion of The Western MindbTango1315100% (1)

- Cognitive Distancing in Stoicism - Stoicism and The Art of Happiness PDFDocument7 pagesCognitive Distancing in Stoicism - Stoicism and The Art of Happiness PDFfluidmindfulness100% (2)