Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ajr 17 19378

Uploaded by

heryanggunOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ajr 17 19378

Uploaded by

heryanggunCopyright:

Available Formats

Pe d i a t r i c I m a g i n g • R ev i ew

Ngo et al.

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

Pediatric Imaging

Review

Neonatal Bowel Disorders:

FOCUS ON:

Practical Imaging Algorithm for

Trainees and General Radiologists

Anh-Vu Ngo1 OBJECTIVE. Neonatal bowel disorders require prompt and accurate diagnosis to avoid

A. Luana Stanescu potential morbidity and mortality. Symptoms such as feeding intolerance, emesis, or failure

Grace S. Phillips to pass meconium may prompt a radiologic evaluation.

CONCLUSION. We discuss the most common neonatal bowel disorders and present a

Ngo AV, Stanescu AL, Phillips GS practical imaging algorithm for trainees and general radiologists.

eonatal bowel disorders com- ferential air-fluid levels. Rectal gas is best as-

N

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

prise a variety of congenital and sessed with a prone view. In the setting of ob-

acquired entities of both the up- struction, the initial abdominal radiographs,

per and lower gastrointestinal in combination with clinical symptoms, help

(GI) tracts. We focus our discussion on the differentiate proximal from distal bowel ob-

most common entities for which radiologic structions. When possible, monitoring equip-

evaluation plays a substantial role in diagno- ment and the comfort pads should be removed

sis. We first outline a general radiologic ap- from the FOV to optimize radiographic evalu-

proach to these disorders and subsequently ation and reduce radiation dose [1, 2].

elaborate on individual diseases. Although Certain neonatal bowel disorders have a pa-

some neonatal bowel disorders may be diag- thognomonic appearance on conventional ra-

nosed prenatally, a discussion of prenatal diographs, precluding the need for further im-

features is largely beyond the scope of this aging. For example, in the setting of isolated

article. With respect to the upper GI tract, we EA or EA with proximal TEF (Gross types A

will describe esophageal atresia (EA) and and B), radiographs show a gasless abdomen.

tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF); pyloric ste- A double bubble on conventional radiographs

nosis; duodenal web, stenosis, and atresia; refers to the gaseous distention of the stomach

and malrotation. Regarding the lower gastro- and a dilated duodenal bulb, and is diagnostic

intestinal tract, we will discuss jejunoileal of duodenal atresia [3]. A triple bubble refers

and colonic atresias, meconium ileus, ano- to the characteristic additional gaseous disten-

rectal malformations, functional immaturity tion of a third hollow viscous—that is, a dilat-

Keywords: bowel, malrotation, microcolon, neonatal,

obstruction of the colon, Hirschsprung disease (HD), and ed proximal jejunal loop—related to a proxi-

necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). mal jejunal atresia [3].

doi.org/10.2214/AJR.17.19378

Imaging Algorithm Fluoroscopy

Received December 6, 2017; accepted after revision

January 5, 2018.

Radiography After conventional radiographs, a fluoro-

The radiographic evaluation of neonatal scopic upper GI series (UGI) is the next step

1

All authors: Department of Radiology, Seattle bowel disorders begins with a supine frontal in the radiologic evaluation of the esopha-

Children’s Hospital, University of Washington School of radiograph of the abdomen. An imaging algo- gus, stomach, and proximal small bowel.

Medicine, 4800 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98105. rithm for bilious emesis, a common present- Suspected malrotation requires an emergent

Address correspondence to G. S. Phillips

ing sign of a neonatal bowel emergency, is UGI, because findings on radiographs can be

(grace.phillips@seattlechildrens.org).

presented in Figure 1. If esophageal patholo- normal. A UGI may also elucidate the anato-

This article is available for credit. gies are suspected, the chest may also be in- my of upper intestinal obstruction when con-

cluded in the examination. If there is clinical ventional radiographs are indeterminate [3].

AJR 2018; 210:976–988

concern for perforation, ischemia, or obstruc- For neonates, a UGI is performed with the

0361–803X/18/2105–976 tion, a left lateral decubitus or cross-table lat- patient recumbent while lateral and frontal

eral view may be obtained to evaluate for free projections of the esophagus, stomach, and

© American Roentgen Ray Society intraperitoneal or portal venous gas and dif- duodenum are obtained. In certain cases,

976 AJR:210, May 2018

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

placement of a nasoenteric tube may assist Ultrasound, CT, and MRI ties, drooling, and cyanosis or apnea while

in control of the contrast bolus. When there In recent years, the role of ultrasound has feeding [11]. At clinical examination, the in-

is concern for TEF, the patient is ideally po- become increasingly defined for particular ability to place a nasogastric tube may be di-

sitioned prone, and contrast agent is instilled neonatal bowel disorders. Ultrasound is the agnostic. Neonates with isolated EA, or EA

into the esophagus in the lateral projection. mainstay for diagnosis in suspected pylor- with a proximal TEF, will have an absence of

Of note, prone imaging in the lateral projec- ic stenosis, with a sensitivity and specifici- abdominal bowel gas on conventional radio-

tion requires use of a mobile C-arm position- ty that approach 100% [4–6]. With respect graphs. With a distal TEF, although the ab-

er fluoroscopy unit. to NEC, sonography complements conven- domen may initially be gasless, bowel gas is

To exclude malrotation, meticulous tech- tional radiography by providing a real-time typically seen after 4 hours of life [12]. Bron-

nique, with both frontal and lateral projec- assessment of bowel peristalsis, perfusion, choscopy is considered the diagnostic test

tions, is required (Fig. 2). Attention must and wall thickness, as well as characteriza- of choice for TEF in the setting of EA [13,

be paid to patient positioning so that fron- tion of peritoneal fluid [6–8]. UGI remains 14]. UGI examination is generally contrain-

tal and lateral projections are obtained with- the study of choice for suspected malrota- dicated in EA because of the risk of aspira-

out obliquity. To study the gastric outlet and tion [6]. Cystic abdominal masses, such as tion [15]. After surgical repair, UGI can help

duodenum, the patient is placed in the right bowel duplication cysts, meconium pseudo- diagnose complications such as anastomotic

lateral decubitus position until contrast agent cysts, and mesenteric cysts, are well depicted leak, which is seen in 15–20% of patients,

distends the second portion of the duode- by sonography. and stricture formation, which is present in

num. The patient is then positioned supine CT and MRI are infrequently used to as- 30–40% of these patients [11].

to document the duodenal-jejunal junction in sess neonatal bowel disorders because of the

the frontal projection. The patient may then inherent radiation dose related to CT and po- Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

be placed in the right lateral decubitus po- tential need for sedation for MRI examina- Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a

sition a second time to document the loca- tions. However, in complex cases, these mo- form of gastric outlet obstruction due to ab-

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

tion of the fourth portion of the duodenum. dalities may be used for problem solving. As normal thickening and elongation of the py-

A normal lateral projection of the duodenum MRI technology advances, the potential for lorus. Although the exact cause of HPS is un-

shows a posterior or retroperitoneal location MRI without sedation using fast MRI se- clear, both environmental and genetic factors

of both the proximal and distal portions of quences may expand its role. A recent study likely contribute to its development. Male

the duodenum. A normal frontal projection showed the feasibility of high-resolution sex, primiparity, prematurity between 28–36

confirms that the duodenal-jejunal junction MRI without sedation in infants up to age weeks’ gestational age, and postnatal eryth-

is to the left of the spine at the level of the py- 4 months with anorectal malformations [9]. romycin exposure are recognized risk fac-

lorus. Ideally, the first bolus of contrast agent tors [16]. In addition, five genetic loci have

is imaged as it passes through the duodenum, Upper Intestinal Neonatal been associated with HPS [16]. HPS typically

because contrast-filled loops of jejunum may Bowel Disorders presents between 2 and 12 weeks of age with

obscure the course of the duodenum on sub- Esophageal Atresia and nonbilious projectile emesis [16]. The classic

sequent boluses. Tracheoesophageal Fistula physical examination sign of a palpable “ol-

Enemas with contrast material (CE) are EA may be seen in isolation or in associ- ive” related to the thickened elongated pyloric

used to define the anatomy of the rectum, co- ation with a TEF. EA has an estimated fre- channel has become less common, likely be-

lon, and distal small bowel, often in the set- quency of 1 in 2500–3000 live births [10]. cause of earlier diagnosis [17].

ting of suspected distal obstruction. A soft- TEFs may be classified on the basis of their In the past, before the refinement of ultra-

tipped catheter is inserted into the rectum, anatomic location and configuration using sound, UGI was used to diagnose HPS. At

and contrast agent is instilled retrograde. the Gross classification (Fig. 3), which in- UGI, contrast agent within a narrowed elon-

Both lateral and frontal rectal images are im- cludes the following: type A, isolated EA; gated pyloric channel results in a “string”

portant to obtain if HD or anorectal malfor- type B, EA with a proximal TEF; type C, sign (Fig. 4A). The impression of the thick-

mation is suspected. The study is considered EA with a distal TEF; type D, EA with both ened muscular channel on the antrum or

complete once opacification of the cecum or proximal and distal TEFs; and type E, TEF duodenum creates the shoulder and mush-

distal small bowel is achieved. Full disten- without EA [11]. Patients with EA, including room signs, respectively. Dynamic evalua-

tion of the colon may be impossible in the up to 65% without TEF, may have addition- tion of the stomach reveals hyperperistalsis

setting of colonic atresia. al anomalies of the cardiovascular, musculo- of the stomach with minimal egress of con-

With both UGI and contrast enema exam- skeletal, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary trast agent. Ultrasound has replaced UGI as

inations, adherence to the ALARA (as low systems [11]. The designation “VACTERL” the study of choice for suspected HPS be-

as reasonably achievable) principle helps to is defined as three or more anomalies of cause of its high sensitivity and specificity

mitigate patient radiation exposure. Suggest- the vertebral, anorectal, cardiac, tracheal, and lack of ionizing radiation. In HPS, the

ed methods to reduce radiation dose to the esophageal, renal, and limb systems without single muscular wall thickness measures

patient include using intermittent pulsed flu- a chromosomal aberration. greater than or equal to 3 mm, and the py-

oroscopy, last image capture, and appropriate Prenatal sonography of fetuses with EA loric channel length measures greater than

collimation; removing the antiscatter grid; may show polyhydramnios and absence of or equal to 15 mm [18] (Fig. 4B). Imaging in

avoiding digital magnification; and shorten- the stomach bubble. If EA is undiagnosed the right lateral decubitus position may help

ing the distance between the patient and the prenatally, patients typically present in the to mitigate a limited acoustic window from

image intensifier. early postnatal period with feeding difficul- a gaseously overdistended stomach [16]. As

AJR:210, May 2018 977

Ngo et al.

with UGI, gastric emptying may be assessed Malrotation UGI remains the imaging method of choice

with ultrasound dynamically. Pylorospasm, Malrotation or intestinal rotation anoma- in the diagnosis of malrotation and midgut

which is a temporary closing of the pyloric lies are a spectrum of conditions caused by volvulus [22, 28, 31]. Diagnosis of malrota-

channel due to muscle spasm, is a pitfall in absent or incomplete bowel rotation during tion on UGI relies on meticulous technique

diagnosis. Pylorospasm can be excluded by the embryologic process of bowel rotation, with documentation of the duodenal course

prolonged or repeat imaging [16]. At our in- which may also lead to abnormal bowel fixa- achieved on both frontal and lateral views,

stitution, we reimage the pylorus with ultra- tion [21]. These conditions can be classified as discussed earlier in the Fluoroscopy sec-

sound after 20–30 minutes if pylorospasm is as true malrotation, atypical malrotation, and tion, ideally during the first bolus of contrast

initially suspected. nonrotation [22]. True malrotation implies agent, because opacification of proximal je-

an abnormal position of the duodenojejunal junal loops may obscure the duodenal seg-

Duodenal Obstruction and Duodenal Atresia junction or ligament of Treitz in the right up- ments and compromise the examination [28].

Duodenal atresia results from failure of per quadrant associated with a high-riding Findings diagnostic for true malrotation in-

gut recanalization during embryologic de- cecum in the mid or upper abdomen, with a clude abnormal position of the duodenojeju-

velopment, which causes a complete obstruc- resultant narrow mesenteric pedicle that can nal junction to the right of the spine and prox-

tion. Duodenal atresia may be seen as an iso- predispose the patient to potentially cata- imal jejunal loops located in the right upper

lated finding or in association with trisomy strophic midgut volvulus and bowel ischemia. abdomen. Of note, right-sided jejunal loops

21. At prenatal sonography, polyhydramnios During embryologic development, attempts at without other associated abnormalities repre-

in combination with a double bubble may be fixation of the abnormally positioned cecum sent a normal anatomic variant in 2% of pa-

present, with fluid distending a dilated stom- will lead to formation of aberrant adhesive tients [32].

ach and proximal duodenum. Common pre- peritoneal bands (Ladd bands) that extend In midgut volvulus, there is a corkscrew

senting symptoms in the undiagnosed neo- from the cecum toward the right abdominal configuration of the duodenum with a ta-

nate are bilious or nonbilious emesis. The wall. These bands can overlay the duodenum pered or beaked appearance [28]. Up to 15%

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

characteristic radiographic double bubble and potentially cause duodenal obstruction of UGI examinations may lead to false-pos-

sign is diagnostic of duodenal atresia in neo- [23, 24]. itive results of malrotation, most commonly

nates (Fig. 5), signifying a gas-filled dilated In patients with atypical malrotation, the due to unrecognized anatomic variants such

stomach and duodenal bulb. Although the re- ligament of Treitz is at or to the left of mid- as duodenal redundancy or duodenum inver-

mainder of the abdomen is typically gasless, line but below the level of the pylorus and sum [31]. Duodenum inversum (Fig. 7) is a

rarely distal gas is seen if an anomalous bili- may be associated with a high-riding or rare, usually asymptomatic, congenital con-

ary duct joins the duodenum on both sides mobile cecum [22, 25, 26]. If atypical mal- dition characterized by a superior and pos-

of the atretic duodenal segment [19]. In this rotation is incidentally diagnosed in old- terior track of the third duodenum before

case, a UGI may confirm the diagnosis of du- er patients without symptoms, observation crossing the midline at a high level above

odenal atresia. is thought to be appropriate for manage- the pancreas toward the ligament of Treitz,

ment, whereas surgery may be considered in which is usually in a normal position [33, 34].

Duodenal Stenosis and Duodenal Web asymptomatic younger patients [22]. Duodenal redundancy or wandering duode-

In contrast to duodenal atresia, duodenal Nonrotation represents an incidental find- num (Fig. 8) will present with a meander-

stenosis and web are partially obstructing ing present in 2% of UGI studies [27] and is ing course of the proximal duodenum, which

lesions. As the name implies, duodenal ste- defined by the absence of embryologic bowel may form one or multiple loops to the right of

nosis is a narrowed (typically second) seg- rotation, with the small bowel positioned in the spine, but crossing the midline at a nor-

ment, as can be seen at UGI, related to in- the right abdomen, whereas the colon will be mal level and also with a normal position of

complete recanalization. A duodenal web is located on the left. In nonrotation, the mes- the ligament of Treitz [31, 34].

a thin membrane that partially obstructs and enteric root is broad, leading to a low risk of In addition, malrotation may be misdiag-

also usually occurs in the second segment midgut volvulus [24, 28, 29]. nosed in the setting of apparent displacement

of the duodenum, at the level of the ampul- The true incidence of malrotation remains of the duodenojejunal junction, which may

la of Vater [20]. At UGI examination, a duo- unknown because many patients may remain be present in children younger than 4 years

denal web may show a windsock deformity, clinically silent; the estimated prevalence is due to ligamentous laxity, in patients with in-

as contrast agent distends a dilated proxi- approximately 1 in 500 live births [30]. Con- dwelling entering tubes, or due to mass effect

mal duodenum and outlines a thin web that genital diaphragmatic hernia, omphalocele, from liver transplant, splenomegaly, or renal

bulges into the nondilated distal segment. A and heterotaxy syndromes have a high associ- or retroperitoneal tumors [24, 28, 31]. The

windsock deformity may also be seen sono- ation with malrotation. Other entities associ- duodenal-jejunal junction may also be dis-

graphically if the distal segment is fluid- or ated with malrotation include duodenal or in- placed in the setting of a distended stomach,

gas-filled, which allows the differentiation testinal atresia or web, biliary atresia, Meckel small bowel, or colon. If UGI results are not

between a duodenal web and duodenal atre- diverticulum, and HD [24, 31]. definitive for the diagnosis of malrotation, a

sia [20]. Of note, duodenal stenosis and web Bilious emesis in a neonate represents small-bowel follow-through or CE may be

are strongly associated with malrotation, an- the classic clinical presentation of malrota- performed, depending on the patient’s clini-

nular pancreas, and a preduodenal portal tion (Figs. 6A–6C). Cases evolving to bowel cal status, to evaluate the cecal position, from

vein, which should be considered in the dif- ischemia will manifest with abdominal pain, which one may infer the length of mesentery.

ferential diagnosis of partial or complete du- distention, hematochezia, and eventually hy- The position of the cecum is however normal

odenal obstruction. povolemic or septic shock with peritonitis. in 20% of cases of malrotation [35, 36].

978 AJR:210, May 2018

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

Lower Gastrointestinal Neonatal chloride ion exchange and leads to dehydra- demonstrate the anus and enteroliths, which

Bowel Disorders tion of the intraluminal contents, resulting in are calcifications of the meconium caused

Jejunoileal Atresia thickened meconium. by mixing of urine secondary to associated

Jejunoileal atresia is thought to arise from Uncomplicated or simple cases of meco- genitourinary anomalies [41, 42]. The esti-

intrauterine vascular insult, which results in nium ileus present radiographically as a typ- mated incidence of anorectal malformation

necrosis and resorption, leading to segmen- ical distal small-bowel obstruction with di- is 1 in 2500–5000 live births [43]. There is

tal stenosis. The frequency is estimated at 1 lated upstream bowel. Complicated cases of an association with trisomy 18 and 21 and

in every 3000–5000 live births [37]. Clini- meconium ileus are defined by the presence VACTERL syndromes; however, most cases

cal presentation is early in life and is charac- of segmental volvulus, atresia, necrosis, or are sporadic.

terized by bilious emesis in proximal atresia perforation [40] and can have a more vari- Radiographically, the appearance is similar

and abdominal distention and failure to pass able radiographic appearance. In the case of to that of other distal obstructions with dilat-

meconium in distal atresia. necrosis or perforation, the leak of meconi- ed upstream bowel loops. Although a CE can-

Radiographic appearance is dependent on um causes an inflammatory response leading not be performed, a voiding cystourethrogram

the site of obstruction and timing of prenatal to meconium peritonitis, which manifests as may be performed to evaluate for associated

injury. In proximal jejunal atresia, the classic peritoneal calcifications and, when walled genitourinary tract anomalies. Management

appearance is a triple bubble, with gaseous off, leads to meconium pseudocyst forma- typically involves an upstream colostomy

distention of the stomach, duodenum, and tion. The meconium peritoneal calcifications and mucous fistula distally. Before attempt-

proximal jejunum (Fig. 9). This is in contra- can be detected either radiographically or so- ed creation of a neorectum, fluoroscopy of

distinction to distal atresia, which is char- nographically. However, pseudocyst forma- the mucous fistula may be useful for presurgi-

acterized by numerous distended loops of tion is best characterized by ultrasound (Fig. cal planning. This evaluation variably shows

bowel (Fig. 10A). Multiple or long-segment 11). A mesenteric pseudocyst can be singu- an unused appearance of the distal colon and

atresias can have a mixed appearance. Re- lar or multiple and may have thickened walls can reveal additional associated genitourinary

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

gardless of the location of small-bowel atre- with irregular septations and associated mu- anomalies, such as fistulas (Fig. 12).

sia, peritoneal calcifications may be present ral calcifications. Colonic atresia is a rare disease with an

secondary to in utero perforation and meco- On CE, similar to distal small bowel atre- incidence of 1 in 66,000 live births [44]. The

nium peritonitis. sia, meconium ileus will present with a mi- three types described in the literature [45]

UGI may be considered for proximal atre- crocolon. However, when contrast material are a colonic membrane (type 1), discontinu-

sia, and CE is indicated for suspected distal is refluxed into the terminal ileum, multiple ity of colon with a fibrous band and an in-

atresia. However, in either case, the exami- characteristic filling defects representative of tact mesentery (type 2), and separated colon

nations may be complementary to exclude the tenacious meconium are present. The use with a mesenteric defect (type 3). As with

an additional distal stenosis or atresia in the of water-soluble contrast agent, rather than anal atresia, this entity can be detected on

former scenario, or malrotation in the clini- barium, is important in this entity because it prenatal ultrasound with dilated fluid filled

cal presence of bilious emesis in the latter is both diagnostic and potentially therapeu- upstream bowel.

scenario. As with conventional radiographs, tic. Water-soluble contrast agents vary in os- Classically, colonic atresia will appear sim-

the fluoroscopic appearance can be vari- molality. In the clinical scenario of meconium ilar to other distal obstructions by convention-

able and is dependent on the location of the ileus, a contrast agent that is hyperosmotic to al radiographic evaluation. At fluoroscopic

atresia. Microcolon is defined as a diffuse- plasma is preferred for therapeutic reasons be- evaluation, the three types are generally indis-

ly small caliber, but normal in length, colon cause it will draw water into the lumen of the tinguishable, with an abrupt cutoff of the co-

(Fig. 10B) and results from a functionally bowel, aiding the disimpaction. Diatrizoate lon typically shown. However, type 1 colonic

unused or underutilized colon. Microcolon meglumine and diatrizoate sodium (Gastro- atresia can have a pathognomonic windsock

is the typical finding on CE for distal small grafin, Bracco Diagnostics) is highly hyperos- sign due to the contrast material distending or

bowel (ileal) and multiple or segmental atre- motic (1940 mOsm/kg water) compared with bulging the pathologic membrane [46].

sias. Conversely, proximal jejunal atresia can other water-soluble agents, such as iothala-

present with a normal appearance of the co- mate meglumine (400 mOsm/kg water; Cys- Functional Immaturity of the Colon

lon on CE. This is due to a larger length of to-Conray II, Mallinckrodt), and care must be Functional immaturity of the colon is also

small bowel that is in continuity to the colon, taken to ensure that the child is adequately hy- known as “small left colon syndrome” and

resulting in a normal utilized appearance. drated, if diatrizoate meglumine with diatri- “meconium plug syndrome.” The latter term

zoate sodium is used. In simple cases of me- may cause confusion because meconium

Meconium Ileus conium ileus, the published success rates for plugs located in the terminal ileum are re-

Meconium ileus is neonatal obstruction of disimpaction with water-soluble enemas is ferred to as “meconium ileus,” as discussed

the distal ileum due to abnormally thick and 5–83% [40]. already. Functional immaturity of the colon

tenacious meconium. Up to 90% of full-term is, however, a transient obstruction of the dis-

neonates with meconium ileus have cystic fi- Imperforate Anus and Colonic Atresia tal colon. In this entity, the meconium materi-

brosis [38]. The frequency of cystic fibrosis Imperforate anus is usually clinically evi- al is in the colon, not the terminal ileum, and it

is 1 in 3500 white live births [39]; it is much dent and may be diagnosed by prenatal ul- is not the underlying cause of the obstruction

rarer in patients of other races. The patho- trasound secondary to dilation of upstream but a consequence of the functional obstruc-

physiology of cystic fibrosis is genetic muta- bowel. Other less common prenatal ultra- tion. The cause of the functional obstruction

tion in the CFTR gene, which alters cellular sound findings of anal atresia are failure to is unclear but is thought to be secondary to

AJR:210, May 2018 979

Ngo et al.

immaturity of the ganglion cells or hormone drome, but the rectosigmoid ratio is usual- resent an impending sign of perforation from

receptors. The frequency is higher in children ly normal (> 1) in small left colon syndrome. full-thickness wall necrosis, to a completely

of diabetic mothers and neonates of mothers Although a transition point may be present at gasless abdomen in the setting of dilated bow-

who receive magnesium sulfate as part of the imaging, correlation with pathologic agangli- el loops filled with fluid [68, 69]. Pneumatosis,

treatment for preeclampsia [47]. These neo- onosis is sporadic. Jamieson et al. [50] showed with curvilinear or bubbly lucencies parallel-

nates typically present with delayed passage an overall concordance of 62.5% between im- ing the bowel wall, represents a pathogno-

of meconium and abdominal distention. The aging and pathologic analysis and, in a sub- monic sign for NEC. Pneumatosis frequently

prognosis is excellent in these cases, and the group of long-segment HD, a concordance involves the right lower quadrant within dis-

symptoms typically resolve in a few days. of only 25%. A sawtooth pattern of the distal tal small bowel and proximal colonic walls,

On conventional radiographs, there can be rectum may be seen at fluoroscopy, represent- although it may occur in any location along

multiple dilated segments of bowel, similar to ing spasm secondary to aganglionosis. Total the gastrointestinal tract [7]. Portal venous gas

other distal obstructions, such as ileal atresia colonic HD may have an appearance similar may be transient and indicates progression to

and meconium ileus. However, in utero bowel to that of microcolon, although a more round- severe disease [70]. Although portal venous

perforation has not been reported, and thus ed configuration of the colon creating a ques- gas is not an indication for surgical interven-

peritoneal calcifications have not been de- tion mark– or comma-shaped colon has been tion, it is significantly associated with the

scribed. On CE, a microcolon should not be described [51]. eventual need for surgery [69]. Pneumoperito-

present. As the alternative name of “small left neum (Fig. 15) remains an absolute indication

colon syndrome” implies, only the distal co- Necrotizing Enterocolitis for surgery and indicates bowel necrosis with

lon will be small, which is distinctly different Despite a gradual decrease in incidence perforation. Of note, pneumoperitoneum is

from microcolon, which is a diffuse process over the last 10 years because of improved absent in more than half of patients with per-

involving the entire colon. Although the distal prevention strategies [52, 53], NEC remains foration and necrosis [7, 71–73].

colon is small, the rectosigmoid ratio should the most common gastrointestinal emergen- The role of ultrasound in NEC varies from

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

remain normal (Fig. 13). Contrast typically cy in neonatal ICUs [54]. The pathogene- institution to institution and is operator de-

outlines meconium plugs within the colon. sis of this inflammatory bowel condition is pendent. Ultrasound does have the potential

thought to be multifactorial, with immature to provide very useful additional informa-

Hirschsprung Disease bowel function, bowel hypoxia or ischemia, tion beyond radiographs alone, particularly

HD is a congenital disorder of the enter- type of enteral feeding, and disruption of gut in centers with experience. Ultrasound has

ic nervous system. The incidence is 1 in ev- microbiota likely representing contributing advantages over radiographs that include

ery 5000 live births [48]. There is a 2.5:1 to factors [52, 54–56]. NEC remains primari- real-time evaluation of bowel peristalsis, wall

5:1 male predilection. Approximately 3–8% ly a disease of premature infants, especially thickness, and perfusion. As such, ultrasound

of cases are familial, with multiple mutations those with birth weight below 1500 g [7, 57, allows diagnosis of NEC in early stages,

identified [49]. It is characterized by absence 58]. However, approximately 10% of cases showing increased bowel wall thickening, in-

of the ganglion cells of the myenteric and are seen in full-term neonates [59], with up creased perfusion, and initial pneumatosis at

submucosal plexus of the rectum and colon. to one-third of these cases presenting in as- a time when radiographs typically show non-

The aganglionic segment lacks the signal sociation with congenital heart disease, par- specific bowel distention [66]. In addition,

to relax and, thus, is in a constant state of ticularly entities predisposing to alterations portal venous gas and pneumoperitoneum

spasm. Neonates typically present with fail- of bowel perfusion, such as left ventricular can be seen at sonography with at least a sim-

ure to pass meconium and abdominal disten- outflow lesions or single ventricle physiolo- ilar sensitivity as radiographs [7, 74]. Adverse

tion. Although the fluoroscopic findings may gy [60–62]. The classic presentation of NEC outcomes may be predicted when abnormal

be suggestive of the diagnosis, imaging alone in premature infants includes abdominal bowel thickness measures above 2.8 mm or

cannot exclude HD, and suction biopsy is re- distention, feeding intolerance, and bloody below 1.1 mm, or when aperistalsis and ab-

quired for definitive diagnosis. stools. In premature infants, NEC typical- sent perfusion, with or without complex free

On conventional radiographs, there is gas- ly occurs in the second or third week of life fluid, are detected on ultrasound [69, 74].

eous distention of numerous loops of bowel, [63]. In contrast, NEC tends to manifest ear-

similar to the other distal obstructions already lier in full-term neonates, during the first Conclusion

discussed. CE classically shows a rectosig- week of life [64, 65]. Radiology plays a fundamental role in

moid diameter ratio of less than 1. Howev- Imaging with radiography and ultrasound the diagnosis of neonatal bowel disorders,

er as previously stated, a rectosigmoid ratio plays an essential role in the diagnosis of as summarized in Table 1. Prompt diagno-

greater than 1 does not exclude HD. CE re- NEC, as well as in monitoring disease pro- sis of these potentially life-threatening con-

mains an important diagnostic test for neo- gression. Radiography remains the imaging ditions requires a methodical diagnostic ap-

nates with suspected HD to evaluate for other modality of choice, with abdominal radio- proach and familiarity with radiographic and

causes of distal obstructions and for preoper- graphs performed every 6 hours [66] dur- fluoroscopic patterns of disease. Although

ative planning. If present, HD nearly always ing the NEC watch until remission of symp- some entities may be diagnosed by prenatal

affects the distal rectum, and more proximal toms and finding, or progression is seen. The ultrasound or MRI, postnatally radiographs

contiguous colonic segments are variably af- bowel gas pattern in NEC can include vari- and fluoroscopy remain the cornerstones of

fected. A transition point is often identified ous findings, ranging from diffuse nonspe- diagnostic imaging for many neonatal bow-

with upstream dilation (Fig. 14), which may cific gaseous distention due to ileus [7, 67] to el disorders. The exception is HPS, in which

mimic the appearance of small left colon syn- fixed dilated loops of bowel, thought to rep- ultrasound has essentially replaced UGI ex-

980 AJR:210, May 2018

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

TABLE 1: Role of Radiology in Diagnosing Neonatal Bowel Disorders

Type of Disorder Diagnostic Test Imaging Findings Pitfalls in Diagnosis and Additional Considerations Current Management

Tracheoesophageal UGI examination Fistulous connection between esophagus and trachea; UGI examination may miss TEFs even with meticulous Surgical repair

fistula refer to Figure 3 for types of TEF technique

Hypertrophic pyloric Ultrasound Persistent abnormal thickening (> 3 mm) and elongation Pylorospasm can mimic pyloric stenosis; consider Pyloromyotomy

stenosis (> 15 mm) of the pyloric channel repeat imaging if pylorospasm is suspected

Duodenal atresia Abdominal radiographs Double bubble: gaseous distention and dilation of the Rarely distal gas is seen if an anomalous biliary duct Duodenoduodenostomy

stomach and duodenum joins the duodenum on both sides of the atretic

duodenal segment

Duodenal stenosis UGI examination Narrowed, typically second duodenal segment Strongly associated with malrotation, annular pancreas, Duodenoduodenostomy

and a preduodenal portal vein

Duodenal web UGI examination Windsock deformity, as contrast agent distends a Strongly associated with malrotation, annular pancreas, Duodenoduodenostomy;

dilated proximal duodenum, and outlines a thin web and a preduodenal portal vein resection of web

that bulges into the nondilated distal segment

Malrotation UGI examination Abnormal position of the duodenal-jejunal junction Duodenum inversum; duodenal redundancy; Ladd procedure

displacement of the duodenal-jejunal junction due to

ligamentous laxity, in patients with indwelling enteric

tubes or due to mass effect from liver transplant,

splenomegaly or renal or retroperitoneal tumors, a

distended stomach, small bowel, or colon

Proximal jejunal Radiographs; UGI Triple bubble sign on radiographs, with gaseous Multiple or long-segment atresias can have a mixed Surgical resection of the atretic

atresia examination distention of the stomach, duodenum, and proximal appearance segment(s)

jejunum; UGI appearance is variable depending on

site of atresia

Distal ileal atresia Contrast enema Microcolon Multiple or long-segment atresias can have a mixed Surgical resection of the atretic

appearance segment(s)

Meconium ileus Contrast enema Microcolon; when contrast material is refluxed into the Complicated cases of meconium ileus are defined by the Enema may be therapeutic

terminal ileum, multiple characteristic filling defects presence of segmental volvulus, atresia, necrosis, or

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

representing tenacious meconium are present perforation, and can have a more variable radiographic

appearance; peritoneal calcifications and pseudocyst

formation (best characterized by ultrasound) may occur

Imperforate anus Physical examination; Distal bowel obstruction Voiding cystourethrogram may be performed to Colostomy before definitive

radiographs evaluate for associated genitourinary tract anomalies surgical repair

Colonic atresia Radiographs; contrast Distal bowel obstruction on radiographs; abrupt cutoff On fluoroscopic evaluation the three types are generally Colostomy before definitive

enema of the colon on enema indistinguishable, although type 1 colonic atresia can surgical procedure

have a pathognomonic windsock sign due to the

contrast material distending or bulging the pathologic

membrane

Functional Radiographs; contrast Distal bowel obstruction by radiographs; on enema, Microcolon should not be present Supportive care

immaturity of the enema the distal colon will be small and the rectosigmoid

colon ratio is normal; contrast material typically outlines

meconium plugs within the colon

(Table 1 continues on next page)

AJR:210, May 2018 981

Ngo et al.

Surgical resection of aganglionic amination for diagnosis. Furthermore, the trast? J Pediatr 2010; 156:852

role of ultrasound in NEC has expanded in 15. Gopal M, Woodward M. Potential hazards of con-

management for perforation

recent years. We reviewed the key radiolog- trast study diagnosis of esophageal atre-

Current Management

Supportive care; surgical

ic features of neonatal bowel disorders that sia. J Pediatr Surg 2007; 42:E9–E10

will facilitate prompt diagnosis. 16. Ranells JD, Carver JD, Kirby RS. Infantile hyper-

trophic pyloric stenosis: epidemiology, genetics,

References and clinical update. Adv Pediatr 2011; 58:195–206

1. Rattan AS, Cohen MD. Removal of comfort pads un- 17. Glatstein M, Carbell G, Boddu SK, Bernardini A,

segment

derneath babies. Acad Radiol 2013; 20:1297–1300 Scolnik D. The changing clinical presentation of

2. Jiang X, Baad M, Reiser I, Feinstein KA, Lu Z. hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: the experience of a

Effect of comfort pads and incubator design on large, tertiary care pediatric hospital. Clin

neonatal radiography. Pediatr Radiol 2016; Pediatr (Phila) 2011; 50:192–195

impending sign of perforation from full thickness wall

The bowel gas pattern in necrotizing enterocolitis can

Pitfalls in Diagnosis and Additional Considerations

nonspecific gaseous distention due to ileus to fixed

46:112–118 18. Iqbal CW, Rivard DC, Mortellaro VE, Sharp SW,

necrosis, to a completely gasless abdomen in the

Enema can be normal; rectal biopsy is reference

St. Peter SD. Evaluation of ultrasonographic pa-

dilated loops of bowel, thought to represent an

3. Maxfield CM, Bartz BH, Shaffer JL. A pattern-

setting of dilated bowel loops filled with fluid

include various findings ranging from diffuse

based approach to bowel obstruction in the new- rameters in the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis rela-

born. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43:318–329 tive to patient age and size. J Pediatr Surg 2012;

4. Hernanz-Schulman M, Sells LL, Ambrosino MM, 47:1542–1547

Heller RM, Stein SM, Neblett WW. Hypertrophic 19. Latzman JM, Levin TL, Nafday SM. Duodenal

pyloric stenosis in the infant without a palpable ol- atresia: not always a double bubble. Pediatr

ive: accuracy of sonographic diagnosis. Radiology Radiol 2014; 44:1031–1034

1994; 193:771–776 20. Yoon CH, Goo HW, Kim E-R, Kim KS, Pi SY.

5. Stunden RJ, LeQuesne GW, Little KE. The im- Sonographic windsock sign of a duodenal web.

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

proved ultrasound diagnosis of hypertrophic py- Pediatr Radiol 2001; 31:856–857

loric stenosis. Pediatr Radiol 1986; 16:200–205 21. Stephens LR, Donoghue V, Gillick J. Radiologi-

standard

6. Hiorns MP. Gastrointestinal tract imaging in cal versus clinical evidence of malrotation, a tor-

children: current techniques. Pediatr Radiol tuous tale: 10-year review. Eur J Pediatr Surg

2011; 41:42–54 2012; 22:238–242

TABLE 1: Role of Radiology in Diagnosing Neonatal Bowel Disorders (continued)

7. Epelman M, Daneman A, Navarro OM, et al. 22. Graziano K, Islam S, Dasgupta R, et al. Asympto-

rectum; total colonic Hirschsprung disease may have

matic malrotation: diagnosis and surgical man-

On radiographs, pneumatosis, portal venous gas, and

Necrotizing enterocolitis: review of state-of-the-

free intraperitoneal air are seen; ultrasound in early

Distal bowel obstruction by radiographs; at enema

with contrast material, rectosigmoid ratio should

ultrasound may also show portal venous gas and

agement. J Pediatr Surg 2015; 50:1783–1790

upstream dilation; sawtooth pattern of the distal

art imaging findings with pathologic correlation.

stages shows increased bowel wall thickening,

23. Lampl B, Levin TL, Berdon WE, Cowles RA.

be < 1; transition point is often identified with

RadioGraphics 2007; 27:285–305

increased perfusion and initial pneumatosis;

8. Anupindi SA, Halverson M, Khwaja A, Jeckovic Malrotation and midgut volvulus: a historical re-

M, Wang X, Bellah RD. Common and uncommon view and current controversies in diagnosis and

Imaging Findings

a similar appearance to microcolon

applications of bowel ultrasound with pathologic management. Pediatr Radiol 2009; 39:359–366

correlation in children. AJR 2014; 202:946–959 24. Langer JC. Intestinal rotation abnormalities and

9. Thomeer MG, Devos A, Lequin M, et al. High midgut volvulus. Surg Clin North Am 2017;

resolution MRI for preoperative work-up of neo- 97:147–159

nates with an anorectal malformation: a direct 25. McVay MR, Kokoska ER, Jackson RJ, Smith SD.

pneumoperitoneum.

comparison with distal pressure colostography/ The changing spectrum of intestinal malrotation:

fistulography. Eur Radiol 2015; 25:3472–3479 diagnosis and management. Am J Surg 2007;

Note—UGI = upper gastrointestinal, TEF = tracheoesophageal fistula.

10. Spitz L. Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal 194:712–717; discussion, 718–719

malformations. In: Ashcraft KW, Holcomb III GW, 26. Mehall JR, Chandler JC, Mehall RL, Jackson RJ,

Murphy JP, eds. Pediatric surgery, 4th ed. Phila- Wagner CW, Smith SD. Management of typical

delphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2005:352–370 and atypical intestinal malrotation. J Pediatr

11. Pinheiro PFM. Current knowledge on esophageal Surg 2002; 37:1169–1172

Abdominal radiographs;

Abdominal radiographs;

atresia. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18:3662–3672 27. Stockmann P. Malrotation. In: Oldham KT,

Diagnostic Test

12. Gedicke MM, Gopal M, Spicer R. A gasless ab- Colombani PM, Foglia RP, Skinner MA, eds.

contrast enema

domen does not exclude distal tracheoesophageal Principles and practice of pediatric surgery.

ultrasound

fistula: the value of a repeat x-ray. J Pediatr Surg Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams &

2007; 42:576–577 Wilkins, 2005:1283–1296

13. Guo W, Li Y, Jiao A, Peng Y, Hou D, Chen Y. 28. Strouse PJ. Disorders of intestinal rotation and

Tracheoesophageal fistula after primary repair of fixation (“malrotation”). Pediatr Radiol 2004;

type C esophageal atresia in the neonatal period: 34:837–851

Type of Disorder

recurrent or missed second congenital fistu- 29. Guzzetta PC Jr. Malrotation, volvulus, and bowel

enterocolitis

la. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45:2351–2355 obstruction. In: Evans SR, ed. Surgical pitfalls:

Hirschsprung

Necrotizing

14. McDuffie LA, Wakeman D, Warner BW. Diagno- prevention and management, chapter 80. Phila-

disease

sis of esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal delphia, PA: Saunders, 2009:819–825

fistula: is there a need for gastrointestinal con- 30. Torres AM, Ziegler MM. Malrotation of the in-

982 AJR:210, May 2018

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

testine. World J Surg 1993; 17:326–331 45. Sutton JB. Imperforate ileum. Am J Med Sci 1889; 61. McElhinney DB, Hedrick HL, Bush DM, et al.

31. Applegate KE, Anderson JM, Klatte EC. Intesti- 98:457–461 Necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates with con-

nal malrotation in children: a problem-solving ap- 46. Winters WD, Weinberger E, Hatch EI. Atresia of genital heart disease: risk factors and outcomes.

proach to the upper gastrointestinal series. the colon in neonates: radiographic findings. AJR Pediatrics 2000; 106:1080–1087

RadioGraphics 2006; 26:1485–1500 1992; 159:1273–1276 62. Bolisetty S, Lui K, Oei J, Wojtulewicz J. A region-

32. Sizemore AW, Rabbani KZ, Ladd A, Applegate 47. Berrocal T, Lamas M, Gutiérrez J, Torres I, Prieto al study of underlying congenital diseases in term

KE. Diagnostic performance of the upper gastro- C, del Hoyo ML. Congenital anomalies of the neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis. Acta

intestinal series in the evaluation of children with small intestine, colon, and rectum. RadioGraphics Paediatr 2000; 89:1226–1230

clinically suspected malrotation. Pediatr Radiol 1999; 19:1219–1236 63. Kliegman RM, Fanaroff AA. Neonatal nec-

2008; 38:518–528 48. de Lorijn F, Kremer LC, Reitsma JB, Benninga rotizing enterocolitis: a nine-year experience. Am J

33. Kim ME, Fallon SC, Bisset GS, Mazziotti MV, MA. Diagnostic tests in Hirschsprung disease: a Dis Child 1981; 135:603–607

Brandt ML. Duodenum inversum: a report and systematic review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 64. Maayan-Metzger A, Itzchak A, Mazkereth R,

review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 2006; 42:496–505 Kuint J. Necrotizing enterocolitis in full-term in-

48:e47–e49 49. Valioulis I, Aubert D, de Billy B, Bawab F, Karam fants: case-control study and review of the litera-

34. Long FR, Mutabagani KH, Caniano DA, Dumont R. A complex chromosomal rearrangement asso- ture. J Perinatol 2004; 24:494–499

RC. Duodenum inversum mimicking mesenteric ciated with Hirschsprung’s disease: a case report 65. Ng S. Necrotizing enterocolitis in the full-term

artery syndrome. Pediatr Radiol 1999; 29:602–604 with a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg neonate. J Paediatr Child Health 2001; 37:1–4

35. Firor HV, Harris VJ. Rotational abnormalities of 2000; 10:207–211 66. Esposito F, Mamone R, Di Serafino M, et al. Diag-

the gut: re-emphasis of a neglected facet, isolated 50. Jamieson D, Dundas S, Belushi S, Cooper M, nostic imaging features of necrotizing enterocoli-

incomplete rotation of the duodenum. Am J Roent- Blair G. Does the transition zone reliably delin- tis: a narrative review. Quant Imaging Med Surg

genol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1974; 120:315–321 eate aganglionic bowel in Hirschsprung’s disease? 2017; 7:336–344

36. Morrison SC. Controversies in abdominal imag- Pediatr Radiol 2004; 34:811–815 67. Daneman A, Woodward S, de Silva M. The radiol-

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

ing. Pediatr Clin North Am 1997; 44:555–574 51. Stranzinger E, DiPietro MA, Teitelbaum DH, ogy of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC): a

37. Tonni G, Grisolia G, Granese R, et al. Prenatal Strouse PJ. Imaging of total colonic Hirschsprung review of 47 cases and the literature. Pediatr Ra-

diagnosis of gastric and small bowel atresia: a disease. Pediatr Radiol 2008; 38:1162–1170 diol 1978; 7:70–77

case series and review of the literature. J Matern 52. Patel AL, Panagos PG, Silvestri JM. Reducing in- 68. Wexler HA. The persistent loop sign in neonatal

Fetal Neonatal Med 2016; 29:2753–2761 cidence of necrotizing enterocolitis. Clin Perinatol necrotizing enterocolitis: a new indication for sur-

38. Kelly T, Buxbaum J. Gastrointestinal manifestations 2017; 44:683–700 gical intervention? Radiology 1978; 126:201–204

of cystic fibrosis. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60:1903–1913 53. Kim JH. Necrotizing enterocolitis: the road to 69. He Y, Zhong Y, Yu J, Cheng C, Wang Z, Li L.

39. Wilmott RW, Tyson SL, Dinwiddie R, Matthew zero. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2014; 19:39–44 Ultrasonography and radiography findings pre-

DJ. Survival rates in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis 54. Zani A, Pierro A. Necrotizing enterocolitis: con- dicted the need for surgery in patients with necro-

Child 1983; 58:835–836 troversies and challenges. F1000Res 2015; 4:1373 tising enterocolitis without pneumoperitoneum.

40. Karimi A, Gorter RR, Sleeboom C, Kneepkens 55. Chen Y, Chang KT, Lian DW, et al. The role of Acta Paediatr 2016; 105:e151–e155

CMF, Heij HA. Issues in the management of sim- ischemia in necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr 70. Coursey CA, Hollingsworth CL, Wriston C, Beam

ple and complex meconium ileus. Pediatr Surg Int Surg 2016; 51:1255–1261 C, Rice H, Bisset G. Radiographic predictors of

2011; 27:963–968 56. Nowicki PT. Ischemia and necrotizing enterocoli- disease severity in neonates and infants with nec-

41. Rolle U, Faber R, Robel-Tillig E, Muensterer O, tis: where, when, and how. Semin Pediatr Surg rotizing enterocolitis. AJR 2009; 193:1408–1413

Hirsch W, Till H. Bladder outlet obstruction 2005; 14:152–158 71. Buonomo C. The radiology of necrotizing entero-

causes fetal enterolithiasis in anorectal malforma- 57. Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. colitis. Radiol Clin North Am 1999; 37:1187–1198

tion with rectourinary fistula. J Pediatr Surg N Engl J Med 2011; 364:255–264 72. Munaco AJ, Veenstra MA, Brownie E, Danielson

2008; 43:e11–e13 58. Murthy K, Yanowitz TD, DiGeronimo R, et al. LA, Nagappala KB, Klein MD. Timing of optimal

42. Lam YH, Shek T, Tang MH. Sonographic features Short-term outcomes for preterm infants with sur- surgical intervention for neonates with necrotiz-

of anal atresia at 12 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet gical necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol 2014; ing enterocolitis. Am Surg 2015; 81:438–443

Gynecol 2002; 19:523–524 34:736–740 73. Robinson JR, Rellinger EJ, Hatch LD, et al. Surgi-

43. Zwink N, Jenetzky E, Brenner H. Parental risk fac- 59. Ostlie DJ, Spilde TL, St Peter SD, et al. Necrotiz- cal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Perinatol

tors and anorectal malformations: systematic review ing enterocolitis in full-term infants. J Pediatr 2017; 41:70–79

and meta-analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2011; 6:25 Surg 2003; 38:1039–1042 74. Silva CT, Daneman A, Navarro OM, et al. Corre-

44. Davenport M, Bianchi A, Doig CM, Gough DC. 60. Polin RA, Pollack PF, Barlow B, et al. Necrotizing lation of sonographic findings and outcome in

Colonic atresia: current results of treatment. enterocolitis in term infants. J Pediatr 1976; necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Radiol 2007;

J R Coll Surg Edinb 1990; 35:25–28 89:460–462 37:274–282

(Figures start on next page)

AJR:210, May 2018 983

Ngo et al.

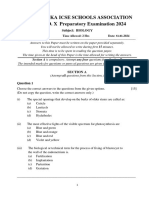

Fig. 1—Imaging algorithm for neonates presenting with bilious emesis. UGI =

Bilious upper gastrointestinal series.

emesis

Abdominal

radiograph

Multiple dilated Few dilated

bowel loops bowel loops

UGI examination

Enema to evaluate to evaluate for

If enema is

for distal bowel malrotation and

negative

obstruction proximal bowel

obstruction

Fig. 2—14-day-old boy with bilious emesis. Contrast

material is seen in stomach.

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

A, Frontal image from fluoroscopic upper

gastrointestinal series (UGI) examination shows

normal position of duodenal-jejunal junction (arrow),

to left of spine (S) at level of pylorus.

B, Lateral image from fluoroscopic UGI examination

shows normal posterior or retroperitoneal position of

both second (black arrows) and fourth (white arrows)

portions of duodenum.

A B

Fig. 3—Gross classification for esophageal atresia

and tracheoesophageal fistulas (TEFs). (Illustrations

by Phillips GS)

A–E, Schematics show type A, isolated esophageal

atresia (A); type B, esophageal atresia with

proximal TEF (B); type C, esophageal atresia with

distal TEF (C); type D, esophageal atresia with both

proximal and distal TEFs (D); and type E, TEF without

esophageal atresia (E).

984 AJR:210, May 2018

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

A B

Fig. 4—3-month-old boy with pyloric stenosis.

A, Lateral image from fluoroscopic upper gastrointestinal series shows characteristic string sign of pyloric

stenosis (arrows). Small amount of contrast material is seen passing distally.

B, Transverse sonogram shows elongated thickened pyloric channel (dotted line) measuring 21 mm in length

with single muscular wall thickness (between calipers) of 5 mm, consistent with pyloric stenosis.

Fig. 5—3-day-old boy with duodenal atresia.

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

Frontal radiograph shows double bubble that

is pathognomonic for duodenal atresia, with

pronounced dilation of gas-filled duodenal bulb

(arrows) related to chronic obstruction. Gas-filled

stomach is partially decompressed by nasogastric

tube. No bowel gas is seen distal to level of

obstruction.

A B C

Fig. 6—6-day-old boy with malrotation and Ladd bands.

A, Frontal abdominal radiograph shows marked gaseous distention of stomach and proximal duodenum, with small amount of bowel gas seen in distal bowel loops in left

hemiabdomen.

B and C, Frontal (B) and lateral (C) images from fluoroscopic upper gastrointestinal series again show marked distention of stomach (S) and proximal duodenum (D), with

abrupt caliber change at level of transverse duodenum suspicious for mechanical bowel obstruction. There is no definite beaking or corkscrew configuration to suggest

midgut volvulus. Although position of ligament of Treitz is not clearly delineated, on frontal view there is opacification of proximal small bowel loops in right hemiabdomen

(arrowheads, B). Malrotation with Ladd bands was confirmed at surgery.

AJR:210, May 2018 985

Fig. 7—4-month-old boy with duodenum inversum.

Ngo et al. A and B, Frontal serial images from fluoroscopic

upper gastrointestinal series show redundant course

of second and third portions of duodenum, with

third portion of the duodenum with initial cephalad

orientation eventually crossing midline above level

of pancreas, consistent with duodenum inversum.

Ligament of Treitz is to left of spine, slightly higher

than duodenal bulb. Arrows outline course of

duodenum.

A B

Fig. 8—2-year-old girl with duodenal redundancy.

A and B, Frontal serial images from fluoroscopic

upper gastrointestinal series show meandering

second duodenum, with normal position of third and

fourth duodenum and of ligament of Treitz. Arrows

outline course of duodenum.

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

A B

A B

Fig. 9—2-day-old boy with proximal jejunal atresia. Fig. 10—0-day-old boy with ileal atresia.

Frontal radiograph of chest and abdomen shows A, Frontal radiograph of abdomen shows diffuse gaseous distention of multiple loops of small bowel indicative

three distinct gas-filled structures representing of more distal obstruction.

stomach (S) and superimposed duodenum (white B, Frontal view from enema with contrast material shows diffuse small caliber of colon, consistent with

arrows) and proximal jejunum (black arrows). microcolon. Appendix (arrow) is partially opacified with contrast material. Note that partially imaged rectum is

wider than sigmoid colon, resulting in normal rectosigmoid ratio.

986 AJR:210, May 2018

Imaging of Neonatal Bowel Disorders

Fig. 11—1-day-old boy with

meconium peritonitis and

pseudocyst.

A, Cross-table lateral radiograph

of abdomen shows distended

abdomen with faint curvilinear

calcifications (arrows) in lower

anterior abdomen.

B, Transverse sonogram of right

lower quadrant shows irregular

cyst (arrow) with internal

echogenic debris.

A B

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

Fig. 12—7-month-old boy with imperforate anus and Fig. 13—1-day-old boy with functional immaturity Fig. 14—2-week-old boy with long-segment

rectourethral fistula. Lateral view from antegrade of left colon. Frontal view from enema with contrast Hirschsprung disease. Frontal view from enema with

enema with contrast material through anterior material shows small left colon (arrows). Transverse contrast material shows transition point (arrow)

abdominal wall mucous fistula shows fistulous (T) and ascending colon are normal. Note that near splenic flexure. Although this may initially be

communication (long white arrow) between rectum rectosigmoid ratio is normal. confused with functional immaturity of colon, rectum

(R) and urethra (black arrows), with contrast material is not widest portion of colon, raising suspicion of

also faintly opacifying bladder (short white arrows). long segment Hirschsprung disease, which was

Note that metallic BB (black dot) was placed at confirmed with biopsy.

expected position of anus on perineum to aid in

presurgical planning.

AJR:210, May 2018 987

Ngo et al.

Fig. 15—9-day-old 24-week-premature girl with

necrotizing enterocolitis and pneumoperitoneum.

A and B, Frontal chest and abdomen radiograph (A)

shows multiple distended stacked bowel loops, with

large pneumoperitoneum (arrows), which is better

seen on left lateral decubitus view (arrows, B). No

definite pneumatosis or portal venous gas were

present. Changes of surfactant deficiency disorder

are noted in bilateral lungs.

American Journal of Roentgenology 2018.210:976-988.

A B

F O R YO U R I N F O R M AT I O N

This article is available for CME and Self-Assessment (SA-CME) credit that satisfies Part II requirements for

maintenance of certification (MOC). To access the examination for this article, follow the prompts associated with

the online version of the article.

988 AJR:210, May 2018

You might also like

- Fruitarians Are The Future Full Guide To Mono-Meals and Fruitarian LivingDocument104 pagesFruitarians Are The Future Full Guide To Mono-Meals and Fruitarian Livinganja79100% (1)

- Hayashi Reiki ManualDocument14 pagesHayashi Reiki Manualboomerb100% (4)

- Harvard Tools For Small Animal SurgeryDocument7 pagesHarvard Tools For Small Animal SurgeryJoel GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Human Body Systems Unit-8 6404 Ppt-1Document53 pagesHuman Body Systems Unit-8 6404 Ppt-1chohan artsNo ratings yet

- Case Study On LeukemiaDocument55 pagesCase Study On LeukemialicservernoidaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Malocclusion of The Teeth and Fractures of The Maxillae. Angle's System. 1900Document338 pagesTreatment of Malocclusion of The Teeth and Fractures of The Maxillae. Angle's System. 1900MIREYANo ratings yet

- Os 206: Pe of The Abdomen - ©spcabellera, Upcm Class 2021Document4 pagesOs 206: Pe of The Abdomen - ©spcabellera, Upcm Class 2021Ronneil BilbaoNo ratings yet

- New School Health FormsDocument42 pagesNew School Health FormsJoanna MarieNo ratings yet

- Practical Algorithms in Pediatric GastroenterologyDocument4 pagesPractical Algorithms in Pediatric GastroenterologyHitesh Deora0% (1)

- Walker - Explorarea Radiologica A Tubului DigestivDocument11 pagesWalker - Explorarea Radiologica A Tubului DigestivDiana AndriucNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Lung Disorders: Pattern Recognition Approach To DiagnosisDocument12 pagesNeonatal Lung Disorders: Pattern Recognition Approach To DiagnosisMeiriyani LembangNo ratings yet

- Feline Abdominal Ultrasonography: What'S Normal? What'S Abnormal?Document14 pagesFeline Abdominal Ultrasonography: What'S Normal? What'S Abnormal?Ветеринарная хирургия Dvm Тозлиян И. А.No ratings yet

- Imaging Patients With Acute Abdominal PainDocument16 pagesImaging Patients With Acute Abdominal PainNaelul IzahNo ratings yet

- Plain Abdominal Radiography in Infants and Children: Hee Jung Lee, M.DDocument7 pagesPlain Abdominal Radiography in Infants and Children: Hee Jung Lee, M.DkishanNo ratings yet

- GI Journal 4Document12 pagesGI Journal 4evfikusmiranti54No ratings yet

- HealthDocument1 pageHealthUp ApNo ratings yet

- Translate Medscape REF 02Document2 pagesTranslate Medscape REF 02Pridina SyadirahNo ratings yet

- GI Journal 1Document15 pagesGI Journal 1evfikusmiranti54No ratings yet

- Transabdominal Sonography in Assessment of The Bowel in AdultsDocument16 pagesTransabdominal Sonography in Assessment of The Bowel in AdultsСергей СадовниковNo ratings yet

- ACG Clinical Guideline Diagnosis and Management.17 PDFDocument21 pagesACG Clinical Guideline Diagnosis and Management.17 PDFPrakashNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Studies - GI BleedingDocument21 pagesDiagnostic Studies - GI BleedingnoemilauNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Management of Early Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of The Esophagus - Screening, Diagnosis, and Therapy AGA 2018Document16 pagesEndoscopic Management of Early Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of The Esophagus - Screening, Diagnosis, and Therapy AGA 2018Nishiby PhạmNo ratings yet

- Wa0002Document14 pagesWa0002Katya RizqitaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic DecisionDocument9 pagesDiagnostic DecisionfrigandraNo ratings yet

- Jehle1989 Emergency Department Sonography byDocument7 pagesJehle1989 Emergency Department Sonography byMohammed NgNo ratings yet

- Mikrokolon & TerjemahanDocument35 pagesMikrokolon & Terjemahanizza mumtazatiNo ratings yet

- Intraabdominal Mass in NewbornDocument8 pagesIntraabdominal Mass in NewbornSridhar KaushikNo ratings yet

- VIBE MRI For Evaluating The Normal and Abnormal Gastrointestinal Tract in FetusesDocument6 pagesVIBE MRI For Evaluating The Normal and Abnormal Gastrointestinal Tract in FetusesakshhayaNo ratings yet

- Cystic Hepatic Lesions: A Review and An Algorithmic ApproachDocument13 pagesCystic Hepatic Lesions: A Review and An Algorithmic Approachhusni gunawanNo ratings yet

- Barrett's Esophagus ACG 2017Document21 pagesBarrett's Esophagus ACG 2017Adhytia PradiarthaNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound AND Congenital Dislocation OF THE HIP: From Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, OxfordDocument5 pagesUltrasound AND Congenital Dislocation OF THE HIP: From Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre, OxfordRéka TéglásNo ratings yet

- Annular PankreasDocument3 pagesAnnular PankreasAnonymous ocfZSRrrONo ratings yet

- David J Ott - 1988 - Current Problems in Diagnostic RadiologyDocument28 pagesDavid J Ott - 1988 - Current Problems in Diagnostic RadiologysharfinaNo ratings yet

- Role of Multimodality Imaging in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications, With Clini-Cal and Pathologic CorrelationDocument28 pagesRole of Multimodality Imaging in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Its Complications, With Clini-Cal and Pathologic CorrelationKaren ojedaNo ratings yet

- Mesenteric Cyst in InfancyDocument27 pagesMesenteric Cyst in InfancySpica AdharaNo ratings yet

- Usefulness of Ultrasonography in Children With Right Iliac Fossa PainDocument12 pagesUsefulness of Ultrasonography in Children With Right Iliac Fossa PainVijayakumar VenugopalNo ratings yet

- Do We Need Anorectal Physiology Work Up in The Daily Colorectal Praxis?Document6 pagesDo We Need Anorectal Physiology Work Up in The Daily Colorectal Praxis?soudrackNo ratings yet

- Spence 2009Document18 pagesSpence 2009Amma CrellinNo ratings yet

- En - 0120 9957 RCG 32 03 00258Document10 pagesEn - 0120 9957 RCG 32 03 00258gvstbndyhkNo ratings yet

- Practical-Algorithms-Diare KronisDocument20 pagesPractical-Algorithms-Diare KronisTiwi QiraNo ratings yet

- Clinical Imaging: Small-Bowel Obstruction: State-of-the-Art Imaging and Its Role in Clinical ManagementDocument1 pageClinical Imaging: Small-Bowel Obstruction: State-of-the-Art Imaging and Its Role in Clinical ManagementDavis KallanNo ratings yet

- Cutoffs and Characteristics of Abnormal Bowel.10Document6 pagesCutoffs and Characteristics of Abnormal Bowel.10sacit17145No ratings yet

- Inside StoryDocument3 pagesInside StoryAutismeyeNo ratings yet

- Fritzienico Zachary B - 20711031 - Naura Soraya H. A - 20711207 - Penugasan Jurnal Checklist STARDDocument24 pagesFritzienico Zachary B - 20711031 - Naura Soraya H. A - 20711207 - Penugasan Jurnal Checklist STARDFritzienico BaskoroNo ratings yet

- Neorev - Emergencias Quirúrgicas Abdominales en NeoDocument10 pagesNeorev - Emergencias Quirúrgicas Abdominales en NeoLuis Ruelas SanchezNo ratings yet

- Acquired Gastrointestinal Fistulas-Classification, Etiologies, and Imaging EvaluationDocument15 pagesAcquired Gastrointestinal Fistulas-Classification, Etiologies, and Imaging EvaluationAle LizárragaNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Masses in The Newborn: Marshall Z. Schwartz, MD, and Donald B. Shaul, MDTDocument10 pagesAbdominal Masses in The Newborn: Marshall Z. Schwartz, MD, and Donald B. Shaul, MDTAditya Rahman RYNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002937821006761Document3 pagesPIIS0002937821006761tasnishapeer15No ratings yet

- Apple Peel Small Bowel, A Review of Four Cases: Surgical and Radiographic AspectsDocument8 pagesApple Peel Small Bowel, A Review of Four Cases: Surgical and Radiographic AspectsraecmyNo ratings yet

- 50 FullDocument8 pages50 FullVincent LeongNo ratings yet

- Review Article The Management of Pelvic Floor DisordersDocument15 pagesReview Article The Management of Pelvic Floor DisordersYvonne MedinaNo ratings yet

- Evaluación de La Deglución Con Nasofibroscopía en Pacientes HospitalizadosDocument7 pagesEvaluación de La Deglución Con Nasofibroscopía en Pacientes HospitalizadosDANIELA IGNACIA FERNÁNDEZ LEÓNNo ratings yet

- Usefulness of Ultrasound Examinations in The Diagnostics of Necrotizing EnterocolitisDocument9 pagesUsefulness of Ultrasound Examinations in The Diagnostics of Necrotizing EnterocolitisSuhartiniNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Practical Approach To Imaging of The Pediatric Acute AbdomenDocument18 pages2017 - Practical Approach To Imaging of The Pediatric Acute AbdomenRevivo RindaNo ratings yet

- Imaging in Pediatric Small Bowel Transplantation: Ransplant MagingDocument11 pagesImaging in Pediatric Small Bowel Transplantation: Ransplant Magingfakhriyyatur rahmi mNo ratings yet

- Common and Uncommon Applications of Bowel Ultrasound With Pathologic Correlation in ChildrenDocument14 pagesCommon and Uncommon Applications of Bowel Ultrasound With Pathologic Correlation in Childrengrahapuspa17No ratings yet

- 498 1004 1 SM PDFDocument5 pages498 1004 1 SM PDFFadhilWNo ratings yet

- Congenital Pyloric Atresia With Distal Duodenal Atresia-Role of CT ScanDocument3 pagesCongenital Pyloric Atresia With Distal Duodenal Atresia-Role of CT Scanhaidar HumairNo ratings yet

- Non Neurogenic CUR Treatment Algorithm: History, Physical Exam, Urine Analysis/culture, GFR, Renal UltrasoundDocument1 pageNon Neurogenic CUR Treatment Algorithm: History, Physical Exam, Urine Analysis/culture, GFR, Renal UltrasoundFitrii WulanDari FitriNo ratings yet

- Role of Gastric Ultrasound To Guide Enteral.9 PDFDocument6 pagesRole of Gastric Ultrasound To Guide Enteral.9 PDFRejanne Oliveira100% (1)

- Consensus Statement of Society of Abdominal Radiology Disease-Focused Panel On Barium Esophagography in Gastroesophageal Reflux DiseaseDocument7 pagesConsensus Statement of Society of Abdominal Radiology Disease-Focused Panel On Barium Esophagography in Gastroesophageal Reflux DiseaseromiamryNo ratings yet

- Gomella Sec03 p0167 0300Document134 pagesGomella Sec03 p0167 0300Gabriela GheorgheNo ratings yet

- Imaging The Child With An Abdominal Mass: IDKD 2006Document8 pagesImaging The Child With An Abdominal Mass: IDKD 2006Sylvia TrianaNo ratings yet

- Rectal Computer 2Document5 pagesRectal Computer 2Su-sake KonichiwaNo ratings yet

- GERD in NeonatesDocument16 pagesGERD in Neonatespandu chouhanNo ratings yet

- GI (PBL1) - Mohamad Arbian Karim - FMUI20Document5 pagesGI (PBL1) - Mohamad Arbian Karim - FMUI20Mohamad Arbian KarimNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2211568411000234 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2211568411000234 MainAndres Suarez GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Journal of Population Therapeutics & Clinical PharmacologyDocument6 pagesJournal of Population Therapeutics & Clinical PharmacologyheryanggunNo ratings yet

- Ham Mitt 2019Document11 pagesHam Mitt 2019heryanggunNo ratings yet

- Fix PPT KasusDocument44 pagesFix PPT KasusheryanggunNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Fixxxx 1Document14 pagesJurnal Fixxxx 1heryanggunNo ratings yet

- Fix PPT KasusDocument44 pagesFix PPT KasusheryanggunNo ratings yet

- BronchiectasisDocument71 pagesBronchiectasisvijay1234568883No ratings yet

- Hematology 1 L2 Hematopoiesis LectureDocument4 pagesHematology 1 L2 Hematopoiesis LectureChelze Faith DizonNo ratings yet

- 5090 s04 QP 1Document20 pages5090 s04 QP 1Anonymous 6qork2No ratings yet

- Gerd - NCCP - Kppik 2011 (Hotel Shangri La)Document28 pagesGerd - NCCP - Kppik 2011 (Hotel Shangri La)Fatmala HaningtyasNo ratings yet

- By Taking On Poliovirus, Marguerite Vogt Transformed The Study of All VirusesDocument8 pagesBy Taking On Poliovirus, Marguerite Vogt Transformed The Study of All VirusesYoNo ratings yet

- Lecture Outline: See Separate Powerpoint Slides For All Figures and Tables Pre-Inserted Into Powerpoint Without NotesDocument58 pagesLecture Outline: See Separate Powerpoint Slides For All Figures and Tables Pre-Inserted Into Powerpoint Without NotesJharaNo ratings yet

- Charateristics of NewbornDocument3 pagesCharateristics of NewbornRagupathyRamanjuluNo ratings yet

- Laju Digesti Pada Ikan FiksDocument12 pagesLaju Digesti Pada Ikan FiksfataNo ratings yet

- 05 Polycythemia in The NewbornDocument11 pages05 Polycythemia in The NewbornMorales Eli PediatraNo ratings yet

- Arfa Final PresantationDocument18 pagesArfa Final PresantationChanda DvmNo ratings yet

- Referat Asma Pada AnakDocument18 pagesReferat Asma Pada AnakezuherliNo ratings yet

- HKCEE - Biology - 1997 - Paper I - A PDFDocument15 pagesHKCEE - Biology - 1997 - Paper I - A PDFChinlam210No ratings yet

- Anatomy of The Anterior Abdominal Wall & Groin PDFDocument4 pagesAnatomy of The Anterior Abdominal Wall & Groin PDFmoetazNo ratings yet

- Diseases of The ThyroidDocument303 pagesDiseases of The ThyroidAtu OanaNo ratings yet

- Wolfe-Management of Intracranial Pressure-Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep-2009Document9 pagesWolfe-Management of Intracranial Pressure-Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep-2009Beny RiliantoNo ratings yet

- A Study of Awareness of Livestock Insurance Among The Peooles of Dombivli West.-1Document71 pagesA Study of Awareness of Livestock Insurance Among The Peooles of Dombivli West.-15. Ajit KanavajeNo ratings yet

- Tricuspid Atresia VivekDocument66 pagesTricuspid Atresia Vivekmihalcea alin100% (1)

- 12 Aerobic Gram-Positive BacilliDocument68 pages12 Aerobic Gram-Positive BacilliClarence SantosNo ratings yet

- KISA Biology QPDocument8 pagesKISA Biology QPakif.saitNo ratings yet

- A Case Report On Tinea CorporisDocument4 pagesA Case Report On Tinea CorporisNavita SharmaNo ratings yet

- Đề Thi Thử Số 21- Ngày 17032024Document7 pagesĐề Thi Thử Số 21- Ngày 17032024Pham AcisNo ratings yet

- Soal Olimpiade SmantiDocument7 pagesSoal Olimpiade SmantiGen Dut SNo ratings yet