Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Why Do People See Different Colours? Why Do We See The Shoe and The Dress Differently?

Uploaded by

Анна Олейник0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

311 views4 pagesHow do people see different colours

Original Title

Colours

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentHow do people see different colours

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

311 views4 pagesWhy Do People See Different Colours? Why Do We See The Shoe and The Dress Differently?

Uploaded by

Анна ОлейникHow do people see different colours

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Why do people see different colours?

Why do we see

the shoe and the dress differently?

It looks like the internet is baffled again by the simplest

of things – a shoe.

This, of course, is not the first time people have been

debating the colour of a clothing item as last year we were all

wrapped up in the white/gold or blue/black dress debacle

[deɪ'bɑːkl] провал and now we have the shoe. Is it pink and

white or grey and mint green? Who knows? Well, the person

who originally posted the photo of the shoe assures us that

the physical shoes are actually pink and white but hundreds

of people have been saying on social media that they can see

the shoes as grey and mint green.

It was the dress that captured the attention of the

masses last year with many people saying they see it as

white and gold and others saying it is blue and black,

however, the original poster showed other pictures in which

the dress is definitely blue and black.

But what is the actual reason for the difference in

perception of these colours? It is down to a variety of factors

such as lighting, phone/computer screen display, brains

interpretation and type of sight. There is no reason for

absolute sure, but some photographers have come out to say

that it’s all down to white balance.

What is white balance?

White balance is a feature that many photo editors and

photographers will be familiar with and it refers to the

action of removing colour casts from a photo so that an

object that is physically white, appears white in the photo.

The reason a colour may look different in a photograph than

it is in real life is down to the colour temperature in the

environment when you were taking the picture. If a colour

temperature is ‘cool’ it means there will be more blue tones

in the photo, if the colour temperature is ‘warm’ there will be

more yellow tones in the photo. The dress may have

appeared blue with the colour cast, but after white balance it

can appear white.

You could say it is down to people’s eyes, seeing as we

all have varying ['veərɪ] ratios соотношение of red to green

cones in our eyes which cause everyone to perceive colour in

their own way, but usually in very subtle ['sʌtl] тонкий

differences.

How green is my valley?

Our colour vision starts with the sensors in the back of

the eye that turn light information into electrical signals in

the brain – neuroscientists call them photoreceptors. We

have a number of different kinds of these, and most people

have three different photoreceptors for coloured light. These

are sensitive to blues, greens and reds respectively соответственно,

and the information is combined to allow us to perceive the

full range of colours. Most colour blind men have a weakness

in the photoreceptors for green, so they lose a corresponding

sensitivity to the shades of green that this variety helps to

distinguish.

At the other end of the scale, some people have a

particularly heightened sensitivity to colour. Scientists call

these people tetrachromats, meaning “four colours”, after the

four – rather than three – colour photoreceptors they

possess. Birds and reptiles are tetrachromatic, and this is

what allows them to see into the infrared инфракрасный and

ultraviolet spectra. Human tetrachromats cannot see beyond

the normal visible light spectrum, but instead have an extra

photoreceptor that is most sensitive to colour in the scale

between red and green, making them more sensitive to all

colours within the normal human range. To these individuals,

it is the rest of us who are colour blind, as while most of us

would be unable to easily distinguish an exact shade of

summer-grass-green from Spanish-lime-green, to a

tetrachromat it would seem obvious.

Behind blue eyes

My worry about your inner perception of the colour blue

is a facet of the basic isolation that is part of the human

condition. Even if we think we can really know other people,

we cannot be certain of that knowledge.

Historically, psychologists have adopted a stance called

behaviourism, which acts as if questions about inner

experience are irrelevant. This approach states that if you

call my blue "blue", and you can always tell it from red, and

if we both know it is the correct colour for the sky, my eyes

and the Smurfs, then who cares what the inner experience

is?

There is a lot of mileage ['maɪlɪʤ] in this perspective,

but maybe there is also some wisdom in trying to convince

ourselves that the difference between our inner experiences

is real, and does matter – and, in fact, that some difference

is inevitable. We use common words, and use them to refer

to shared experiences, but nobody can see the same sunset,

merely because perception is a property of the person, not of

the sunset. Because there is something that it is like to be

you, and your “you-ness” is unique, we are certainly seeing

different things when we talk about looking at something

blue, if only because the act of seeing incorporates feelings

and memories, as well as the raw light information arriving

at our eyes.

You might also like

- Elledge Celia - The Basics of Color Psychology. Meaning and Symbolism of Colors - 2020Document53 pagesElledge Celia - The Basics of Color Psychology. Meaning and Symbolism of Colors - 2020Jumbo Zimmy100% (1)

- Do You See What I SeeDocument5 pagesDo You See What I SeeIsabela Rosero CastroNo ratings yet

- Colour AnalysisDocument7 pagesColour AnalysisSteven MarkhamNo ratings yet

- Digital ColorsDocument19 pagesDigital ColorsCheemsNo ratings yet

- 08 - The Function of The Subreality MachineDocument26 pages08 - The Function of The Subreality MachineLuis PuenteNo ratings yet

- Colour VisionDocument6 pagesColour VisionMark UreNo ratings yet

- Thought Paper #1Document7 pagesThought Paper #1bowencouNo ratings yet

- 04 - The First-Person View of The MindDocument12 pages04 - The First-Person View of The MindLuis PuenteNo ratings yet

- GlccolorconnotationsDocument6 pagesGlccolorconnotationsapi-272879715No ratings yet

- Genetics and Colors of Eyes Around the WorldDocument5 pagesGenetics and Colors of Eyes Around the WorldSafeer IqbalNo ratings yet

- The World of Visual Illusions: Optical Tricks That Defy Belief!From EverandThe World of Visual Illusions: Optical Tricks That Defy Belief!Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- A Natural History of Color: The Science Behind What We See and How We See itFrom EverandA Natural History of Color: The Science Behind What We See and How We See itNo ratings yet

- Illusions of Seeing: Exploring the World of Visual PerceptionFrom EverandIllusions of Seeing: Exploring the World of Visual PerceptionNo ratings yet

- The Heartbeat of Trees: Embracing Our Ancient Bond with Forests and NatureFrom EverandThe Heartbeat of Trees: Embracing Our Ancient Bond with Forests and NatureRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Color Blindness-Phs Steam Certificate l1Document3 pagesColor Blindness-Phs Steam Certificate l1api-661284326No ratings yet

- Physiology of Color Blindness With Special Reference To A Case ofDocument41 pagesPhysiology of Color Blindness With Special Reference To A Case ofZoe ZooNo ratings yet

- ColorsDocument5 pagesColorsSafeer IqbalNo ratings yet

- Eliasson, Olafur - "Some Ideas About Colour."Document4 pagesEliasson, Olafur - "Some Ideas About Colour."Marshall BergNo ratings yet

- Konica Minolta Chromameter Color TheoryDocument49 pagesKonica Minolta Chromameter Color TheoryconjugateddieneNo ratings yet

- Impact 2 Video Unit 1Document1 pageImpact 2 Video Unit 1LuciaNo ratings yet

- Color Theory:The Mechanics of Color: Applied and Theoretical Color With Richard KeyesDocument7 pagesColor Theory:The Mechanics of Color: Applied and Theoretical Color With Richard Keyesnishantjain95No ratings yet

- Photospetrometer PCC EnglishDocument45 pagesPhotospetrometer PCC EnglishemilcioraNo ratings yet

- OWI BrE L02 U01 Main Video ScriptsDocument1 pageOWI BrE L02 U01 Main Video ScriptsОля СеменюкNo ratings yet

- Your True Colors: Power Up and Heal with Color PsychologyFrom EverandYour True Colors: Power Up and Heal with Color PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Some Ideas About Colour 109981Document7 pagesSome Ideas About Colour 109981Pamela FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Feel of Colors EssayDocument3 pagesEmotional Feel of Colors Essayapi-483551784No ratings yet

- Lightexperimentwrite UpDocument3 pagesLightexperimentwrite Upapi-307449973No ratings yet

- Ronan Canty - Research Paper 2020Document4 pagesRonan Canty - Research Paper 2020api-497492580No ratings yet

- Color blindness affects millionsDocument3 pagesColor blindness affects millionsUugaa SoNo ratings yet

- Color BlindnessDocument4 pagesColor BlindnessShehroz KhanNo ratings yet

- Color Psychology: BY 07, MAR 2019Document4 pagesColor Psychology: BY 07, MAR 2019HAWEE HCMCNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of ColoursDocument4 pagesThe Psychology of ColoursmaygracedigolNo ratings yet

- Artists’ Master Series: Color and LightFrom EverandArtists’ Master Series: Color and Light3dtotal PublishingNo ratings yet

- Ways of KnowingDocument9 pagesWays of KnowingramanakumarshankarNo ratings yet

- (English (Auto-Generated) ) How Color Blind People See The World (DownSub - Com)Document6 pages(English (Auto-Generated) ) How Color Blind People See The World (DownSub - Com)Trung LêNo ratings yet

- Sense Perception and Reality: A theory of perceptual relativity, quantum mechanics and the observer dependent universeFrom EverandSense Perception and Reality: A theory of perceptual relativity, quantum mechanics and the observer dependent universeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Further Research (Colour Blindness)Document5 pagesFurther Research (Colour Blindness)ABBY LIEW MAY XINGNo ratings yet

- 3rd Report Color Blind TestingDocument10 pages3rd Report Color Blind Testingbertha tandiNo ratings yet

- The Problems of Philosophy (Warbler Classics Annotated Edition)From EverandThe Problems of Philosophy (Warbler Classics Annotated Edition)No ratings yet

- Optical Illusions: An Eye-Popping Extravaganza of Visual TricksFrom EverandOptical Illusions: An Eye-Popping Extravaganza of Visual TricksNo ratings yet

- Remarks on Colour by WittgensteinDocument17 pagesRemarks on Colour by Wittgensteinতারিক মোর্শেদ0% (1)

- ConditionalsDocument2 pagesConditionalsАнна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- Bermuda Triangle - The Legend and TheoriesDocument4 pagesBermuda Triangle - The Legend and TheoriesАнна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- World: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Document3 pagesWorld: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Анна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- World: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Document3 pagesWorld: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Анна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- World: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Document3 pagesWorld: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Анна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- World: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Document3 pagesWorld: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Анна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- World: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Document3 pagesWorld: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Opinions Do You Most Agree With?Анна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- Emotion: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Person Do You Have Most in Common With?Document4 pagesEmotion: Watch The Video Podcast. Which Person Do You Have Most in Common With?Анна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- InfinitiveDocument2 pagesInfinitiveАнна ОлейникNo ratings yet

- Wish Clauses Worksheet Grammar ExplanationDocument2 pagesWish Clauses Worksheet Grammar Explanationpepac41450% (4)

- Verbs and continuous infinitives exercisesDocument2 pagesVerbs and continuous infinitives exercisesАнна Олейник100% (1)

- 2012 HCO Oriented Core ProceduresDocument30 pages2012 HCO Oriented Core ProceduresPancho Perez100% (1)

- Macho Drum Winches Data v1.4Document2 pagesMacho Drum Winches Data v1.4AdrianSomoiagNo ratings yet

- Fluxus F/G722: Non-Intrusive Ultrasonic Flow Meter For Highly Dynamic FlowsDocument2 pagesFluxus F/G722: Non-Intrusive Ultrasonic Flow Meter For Highly Dynamic FlowslossaladosNo ratings yet

- Eco Industrial DevelopmentDocument16 pagesEco Industrial DevelopmentSrinivas ThimmaiahNo ratings yet

- MINI R56 N12 Valve Stem Seal ReplacementDocument9 pagesMINI R56 N12 Valve Stem Seal ReplacementJohn DoeNo ratings yet

- The Trouble With UV LightDocument3 pagesThe Trouble With UV LightSàkâtã ÁbéŕàNo ratings yet

- BBC Learning English 6 Minute English Day-Trip With A DifferenceDocument4 pagesBBC Learning English 6 Minute English Day-Trip With A DifferenceAsefeh KianiNo ratings yet

- Illusion of ControlDocument5 pagesIllusion of Controlhonda1991No ratings yet

- Teaching Styles in PE WCUDocument7 pagesTeaching Styles in PE WCUReliArceoNo ratings yet

- List of Technical Documents: IRB Paint Robots TR-500 / TR-5000Document16 pagesList of Technical Documents: IRB Paint Robots TR-500 / TR-5000Weberth TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Interview Presentations: Steps For Interview Presentation SuccessDocument3 pagesInterview Presentations: Steps For Interview Presentation SuccessAditya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Salem PossessedDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Salem PossessedCharity BurgessNo ratings yet

- Behavior of RC Shallow and Deep Beams WiDocument26 pagesBehavior of RC Shallow and Deep Beams WiSebastião SimãoNo ratings yet

- HD 9 Manual 5900123 Rev F 10 1 13Document60 pagesHD 9 Manual 5900123 Rev F 10 1 13Karito NicoleNo ratings yet

- My ResumeDocument2 pagesMy ResumeSathanandhNo ratings yet

- Finning CAT Event CodesDocument20 pagesFinning CAT Event CodesSebastian Rodrigo Octaviano100% (2)

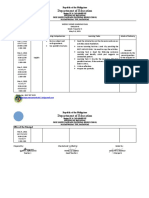

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesEllen Cabatian BanaguasNo ratings yet

- Experiment No. 2 Introduction To Combinational Circuits: Group Name: Group 7 Group Leader: JOSE DOROSAN Group MemberDocument11 pagesExperiment No. 2 Introduction To Combinational Circuits: Group Name: Group 7 Group Leader: JOSE DOROSAN Group MemberJoy PeconcilloNo ratings yet

- 21b Text PDFDocument47 pages21b Text PDFyoeluruNo ratings yet

- Control Systems GEDocument482 pagesControl Systems GECarlos ACNo ratings yet

- V-Qa Full Final (PART-B) PDFDocument104 pagesV-Qa Full Final (PART-B) PDFKoushik DeyNo ratings yet

- Time Table II Sem 14-15Document5 pagesTime Table II Sem 14-15Satyam GuptaNo ratings yet

- Alexandrite: Structural & Mechanical PropertiesDocument2 pagesAlexandrite: Structural & Mechanical PropertiesalifardsamiraNo ratings yet

- GS Ep Saf 321 enDocument27 pagesGS Ep Saf 321 enHi PersonneNo ratings yet

- GOLDEN DAWN 3 8 Highlights of The Fourth Knowledge LectureDocument7 pagesGOLDEN DAWN 3 8 Highlights of The Fourth Knowledge LectureF_RCNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Nikon SLR Handbook Vol 3Document19 pagesThe Ultimate Nikon SLR Handbook Vol 3Katie Freeman50% (4)

- 80312A-ENUS Error LogDocument10 pages80312A-ENUS Error LogSafdar HussainNo ratings yet

- KidzeeDocument16 pagesKidzeeXLS OfficeNo ratings yet

- ) Perational Vlaintena, Nce Manual: I UGRK SeriesDocument22 pages) Perational Vlaintena, Nce Manual: I UGRK Seriessharan kommiNo ratings yet

- Echotrac Mkiii: Model DFDocument2 pagesEchotrac Mkiii: Model DFjonathansolverNo ratings yet