Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jaundice: in Older Children and Adolescents

Uploaded by

hectorOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jaundice: in Older Children and Adolescents

Uploaded by

hectorCopyright:

Available Formats

Article gastroenterology

Jaundice in Older Children and

Adolescents

Dinesh Pashankar, MD,*

Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:

and Richard A. Schreiber,

MD† 1. Describe the basic physiology of bilirubin metabolism, the two standard laboratory

methods for its fractionation, and the classification of jaundice.

2. Characterize the features of Gilbert disease.

3. Identify the leading infectious cause of acute jaundice in older children and

adolescents.

4. Delineate the clinical and biochemical features of Wilson disease and autoimmune

hepatitis.

5. Compare and contrast liver function tests and tests of liver function.

6. Describe the “worrisome” clinical and laboratory signs of hepatic synthetic dysfunction

in jaundiced patients that should prompt an immediate referral to a center where liver

Additional media transplantation is available.

illustrating features of

the disease processes

discussed are available Introduction

in the online version

Jaundice is defined as the presence of a yellow or yellow-greenish hue to the skin, sclera,

of this article at

and mucous membranes due to an elevation of serum bilirubin. In healthy individuals, the

www.pedsinreview.org.

total serum bilirubin is less than 1 mg/dL (17 mcmol/L). Jaundice can be readily detected

clinically when the total serum bilirubin is greater than 5 mg/dL (85 mcmol/L). Clinical

jaundice occurs much less frequently in older children and adolescents than in neonates.

Moreover, the differential diagnosis in this older age group differs markedly from that in

newborns and young infants. This review provides a practical approach to the clinical

evaluation of jaundice in the older child or adolescent. Because jaundice may be the

presenting feature of life-threatening conditions such as ful-

minant liver failure, a prompt and logical evaluation is nec-

essary to identify the more serious disorders that require

urgent management.

Abbreviations

ALP: alkaline phosphatase Bilirubin Metabolism

ALT: alanine aminotransferase Bilirubin is a product of heme metabolism. Heme is con-

ANA: antinuclear antibody verted in the reticuloendothelial (RE) system to biliverdin

ASMA: anti-smooth muscle antibody and then to bilirubin by heme oxygenase and biliverdin

AST: aspartate aminotransferase reductase, respectively. Bilirubin is lipophylic and is bound to

CNS: central nervous system serum albumin in circulation from the RE system to the liver.

EBV: Epstein-Barr virus The liver takes up the bilirubin-albumin complex through an

GGT: gamma glutamyltransferase albumin receptor. Bilirubin, but not albumin, is transferred

HAV: hepatitis A virus across the hepatocyte membrane and transported through

HBV: hepatitis B virus the cytoplasm to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum bound

HCV: hepatitis C virus primarily to ligandin or Y protein, a member of the glutathi-

KF: Kayser-Fleischer one S-transferase gene family of proteins. There, the water-

PT: prothrombin time insoluble bilirubin is conjugated to water-soluble bilirubin

RE: reticuloendothelial monoglucuronide and diglucuronide by UDP-glucuronosyl

transferase. The bilirubin conjugates are excreted through

*Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Gastroenterology, Children’s Hospital of Iowa, Iowa City, IA.

†

Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Division of Gastroenterology, British Columbia’s

Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001 219

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

Table 1. Fractionation of Bilirubin Causes of

Table 2.

Diazo® Method Hyperbilirubinemia in Older

Total bilirubin ⴝ Direct bilirubinm ⴙ Indirect bilirubinm Children

Ektachem® Slide Method Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

Total bilirubinm ⴝ Conjugated bilirubinm ⴙ Hemolytic anemias

Unconjugated bilirubinm ⴙ Delta bilirubin Gilbert syndrome

The Diazo method measures the direct and indirect Crigler-Najjar syndrome

bilirubin and calculates the total. In the Ektachem Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

slide method, the total, conjugated, and

unconjugated bilirubin fractions are measured and Viral Infections

the delta bilirubin is calculated. m ⴝ measured. Hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, E

Epstein-Barr virus

Cytomegalovirus

Herpes simplex

the canalicular membrane into the bile duct system by an Metabolic Liver Disease

energy-dependent process. Conjugated bilirubin flows in Wilson disease

the bile to the intestine, where it is broken down by gut Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency

flora to urobilinogen and stercobilin. Cystic fibrosis

Biliary Tract Disorders

Total serum bilirubin consists of an unconjugated Cholelithiasis

fraction and conjugated fraction of bilirubin and a frac- Cholecystitis

tion of bilirubin glucuronide that is bound covalently to Choledochal cyst

albumin known as delta-bilirubin. The newer Ektachem威 Sclerosing cholangitis

slide method for bilirubin fractionation accurately mea- Autoimmune Liver Disease

Type 1 (anti-smoooth muscle antibody)

sures the levels of unconjugated, conjugated, and total Type 2 (anti-liver-kidney-microsomal antibody)

serum bilirubin. Delta-bilirubin concentration can be Hepatotoxins

calculated from these figures (Table 1). With the tradi- Drugs: Acetaminophen

tional Diazo威 method for bilirubin fractionation, indirect Anticonvulsants

and direct bilirubin are measured and the total bilirubin Anesthetics

Antituberculous agents

is calculated. Unconjugated or indirect hyperbiliru- Chemotherapeutic agents

binemia is defined biochemically by an increased total Antibiotics

serum bilirubin level with less than 15% of the bilirubin in Oral contraceptives

the direct or conjugated form. Conjugated or direct Other: Alcohol, insecticides, organophosphates

hyperbilirubinemia is characterized by the conjugated or Vascular Causes

Budd-Chiari syndrome

direct fraction being greater than 20% of the total serum Veno-occlusive disease

bilirubin.

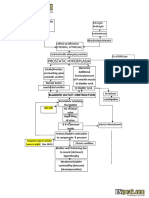

Differential Diagnosis phosphate dehydrogenase, or a hemoglobinopathy

The differential diagnosis of jaundice in an older child is (eg, sickle cell anemia and thalassemia). In these condi-

extensive, encompassing some common conditions and tions, significant hemolysis leads to excess heme produc-

many rare disorders (Table 2). A key practical first step is tion and consequent increased circulating unconjugated

to classify the jaundice as unconjugated (indirect) or bilirubin load.

conjugated (direct) hyperbilirubinemia by using the pre- Gilbert syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder

viously noted Diazo or Ektachem method. seen in 5% of the population, is another important cause

of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in this age group.

Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia This inherited disorder of bilirubin metabolism is char-

Older children and adolescents who present with acterized by a mild unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia

jaundice due to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia are (usually 5 mg/dL [⬍85 mcmol/L]) due to a UGT1

most likely to have a disorder associated with excessive gene mutation that impairs the function of the UDP

hemolysis, such as hereditary spherocytosis, a red blood glucuronosyl transferase enzyme. In affected adolescents

cell enzyme defect of pyruvate kinase or glucose-6- or young adults, jaundice appears most often in associa-

220 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

tion with an intercurrent mild infectious illness, fasting, aminotransferase (ALT) as well as a conjugated hyperbi-

or physical stress. Other than the modest elevation in lirubinemia. Clinical symptoms and biochemical abnor-

unconjugated bilirubin, patients who have Gilbert syn- malities completely resolve within 4 weeks in most pa-

drome are healthy and have no clinical or laboratory tients. In rare cases, HAV can cause relapsing or

evidence of liver disease or hemolysis. An associated persistent jaundice for months. However, HAV infection

family history, although not always present, is diagnostic never leads to a chronic hepatitis, defined as hepatitis

for the condition. There are no specific diagnostic labo- lasting for more than 6 months. Fulminant HAV infec-

ratory tests. The prognosis is excellent, with no long- tion, heralded by encephalopathy and significant hepatic

term sequelae. dysfunction (ie, coagulopathy), is distinctly unusual, oc-

The Crigler-Najjar syndromes types 1 and 2 are ex- curring in fewer than 1% of cases. Indeed, although viral

tremely rare autosomal recessive diseases that result from or presumed viral hepatitis accounts for 75% to 80% of all

a complete absence (type 1) or limited activity (type 2) of cases of fulminant liver failure in children, most of these

the UDP-glucuronosyl transferase enzyme. Both condi- are the result of non-A through G hepatitis viruses.

tions typically manifest as an unconjugated hyperbiliru- The majority of pediatric patients who have hepatitis

binemia in the first few days of life, although exceptional B virus (HBV) infection are asymptomatic. However,

cases of Crigler-Najjar type 2 presenting at an older age jaundice may occur in acutely infected older children.

have been reported. Without the ability to conjugate The most important routes for acquiring acute HBV

and excrete bilirubin, patients who have type 1 disease infection in adolescence are horizontal—from highly in-

exhibit markedly elevated serum bilirubin levels (25 to fectious family members, from improperly sterilized sy-

35 mg/dL) [425 to 600 mcmol/L]), are at high risk ringes, or when adolescents practice high-risk sexual

to develop kernicterus, and require aggressive photo- behavior with multiple partners and infrequent use of

therapy. In contrast, patients who have type 2 disease condoms. Many older children and adolescents chroni-

usually have total serum bilirubin levels below 20 mg/dL cally infected with HBV are foreign immigrants from

(350 mcmol/L) because of the partially functioning endemic regions who had acquired infection through

UDP-glucuronosyl transferase enzyme, whose activity perinatal transmission. Older children who have chronic

can be induced by phenobarbital. Indeed, the two types HBV infection are often asymptomatic carriers or they

of Crigler-Najjar syndrome may be distinguished by may have a limited, subclinical, biochemical hepatitis,

treatment with phenobarbital. Patients who have type 1 evidenced by increased hepatic transaminase levels. Jaun-

disease show no response; those who have type 2 disease dice is an unusual manifestation in children who have

exhibit a dramatic decrease in serum bili rubin levels chronic HBV infection, except in the rare instance of

following the administration of phenobarbital. fulminant liver failure or end-stage liver disease and

cirrhosis developing at a young age.

Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia Most children who have hepatitis C virus (HCV)

INFECTIONS infection are older than 8 years of age and have con-

Infection with any of the hepatotropic viruses (A, B, C, tracted the infection through contaminated blood and

D, or E) may cause jaundice in older children and ado- blood products prior to 1992. With improved processing

lescents. In these instances, the jaundice is due to conju- of blood and blood products, the chance of contracting

gated hyperbilirubinemia resulting from intrahepatic HCV through these sources is now low, estimated at 1

cholestasis. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection, a self- per 100,000 units transfused. The more important

limited illness induced by an RNA virus, is the most source for pediatric HCV infection is through maternal-

common infectious cause of acute jaundice in this age infant transmission. This indolent disease takes many

group. Young infants rarely develop jaundice when in- decades to progress to end-stage liver disease. Thus, the

fected with HAV. Infants and young children who have vast majority of older children infected with this virus are

HAV infection are usually asymptomatic or simply man- asymptomatic. However, as with chronic HBV infection,

ifest signs and symptoms of viral gastroenteritis without jaundice may manifest in those very rare patients who

icterus. In contrast, older children and adolescents have a have HCV infection and develop cirrhosis at an early age.

prodrome of fever, headache, and general malaise fol- Hepatitis D virus infection is uncommon in the United

lowed by the onset of jaundice, abdominal pain, nausea, States, occurring only in patients already infected with

vomiting, and anorexia. There is biochemical evidence of HBV. Hepatitis E virus is prevalent in developing coun-

a profound hepatitis characterized by significant eleva- tries and typically presents acutely with jaundice, in a

tions in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine manner similar to HAV infection.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001 221

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection can cause acute Skeletal manifestations resulting from bone demineral-

hepatitis and jaundice in older children and adolescents ization are not uncommon.

as a part of the infectious mononucleosis syndrome. Any Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, an autosomal codomi-

child or adolescent who presents acutely with jaundice, nantly inherited disease, can present with a conjugated

especially in association with lymphadenopathy, sore hyperbilirubinemia at any age. Approximately 20% of

throat, and mild splenomegaly, should be evaluated for patients who have the ZZ protease inhibitor phenotype

EBV infection. In immunocompromised hosts, infection will have liver disease. Although neonatal cholestasis is a

with herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, or rare op- more common presentation for this disorder, older chil-

portunistic agents can cause hepatobiliary disease with dren may have new-onset jaundice in association with

clinical jaundice, but a discussion of these is beyond the alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, chronic hepatitis, or

scope of this article. Jaundice with hepatic dysfunction as cirrhosis.

a result of gram-negative bacterial infections and sepsis is Hepatobiliary disease may occur in up to two thirds of

much more common in infants and young children than patients who have cystic fibrosis. Pancreatic insufficiency

in older children and adolescents. and pulmonary disease used to be the dominant features

of cystic fibrosis, which was associated with high morbid-

METABOLIC LIVER DISEASE ity and mortality at a young age. With improved treat-

A variety of metabolic diseases of the liver may present ments and longer life expectancy, liver disease has as-

with jaundice in older children. Wilson disease is an sumed greater importance, especially for older children

autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism, char- and adolescents. The spectrum of hepatobiliary disorders

acterized by excess accumulation of copper in the liver, in cystic fibrosis includes steatohepatitis, focal biliary and

central nervous system (CNS), kidney, cornea, and other multilobular cirrhosis, cholelithiasis and cholecystitis,

organs. The hepatic manifestations are protean, ranging sclerosing cholangitis, and common bile duct stenosis.

from an acute hepatitis to fulminant hepatic failure with Any of these complications may be heralded by a conju-

coagulopathy, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy or a gated hyperbilirubinemia.

more indolent course with chronic hepatitis and cirrho-

sis. Wilson disease must be considered in the differential BILIARY TRACT DISORDERS

diagnosis of every older child or adolescent who presents Extrahepatic biliary tract disorders may cause an obstruc-

with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Neuropsychiatric tive type of jaundice that is manifested by icterus, dark

features may be dramatic, including motor system distur- urine, acholic stools, and pruritus in association with a

bances such as tremor, incoordination, and dysarthria, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Cholelithiasis can occur

along with poor school performance, depression, neuro- in older children, albeit infrequently. Gallstones in this

sis, or psychosis. The CNS manifestations may present in age group may be idiopathic or may develop due to

concert with or independent of the hepatic symptoms. hemolytic disorders, cystic fibrosis, obesity, ileal resec-

Kayser-Fleischer (KF) rings, a golden brown discolora- tion, or long-term use of total parenteral nutrition. Al-

tion in the zone of the Descemet membrane of the though many children who have gallstones are asymp-

cornea, is virtually always present when neurologic or tomatic, jaundice, periumbilical or right upper quadrant

psychiatric symptoms develop. However, KF rings may abdominal pain, vomiting, and fever may develop in cases

be absent in patients who have Wilson disease without of acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, or pancreati-

neurologic involvement but who present with hepatic tis. Ultrasonography is the safest, most sensitive, and

symptoms. Renal involvement is characterized by proxi- most specific method of identifying gallstones.

mal tubular dysfunction, decreased glomerular filtration Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilatations of

rate, and decreased renal plasma flow. Patients may man- the intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary ducts. At least five

ifest proteinuria, glucosuria, phosphaturia, uricosuria, subtypes have been described based on the anatomic site

aminoaciduria, renal tubular acidosis, and microscopic of cystic dilation along the biliary tree. Patients may

hematuria. Severe renal insufficiency may occur in pa- present at any age with epigastric pain, fever, and jaun-

tients who have fulminant or end-stage liver disease. dice. The most useful diagnostic study is abdominal

Intravascular hemolysis with a Coombs-negative hemo- ultrasonography. In older children, acute jaundice may

lytic anemia may develop because of the oxidative injury develop in cases of intrahepatic cystic duct lesions that are

to red blood cell membranes induced by excess copper. associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis and autosomal

Cardiac involvement, including ventricular hypertrophy recessive polycystic kidney disease.

and arrhythmias, has been reported in Wilson disease. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a chronic fibro-

222 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

obliterative disease of unknown etiology that involves can cause jaundice include erythromycin, sulfonamides,

the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts. In older halothane, methotrexate, chemotherapy, anticonvul-

children, this condition occurs most often in association sants such as valproate and phenytoin, the antitubercu-

with inflammatory bowel disease, although it may lous drug isoniazid, and oral contraceptives.

present rarely in otherwise healthy teenagers or in pa-

tients who have congenital or acquired immunodefi- VASCULAR DISEASES

ciency. Clinical features include jaundice, anorexia, fa- Vascular diseases of the liver may present with jaundice in

tigue, abdominal pain, and pruritus. The diagnosis is older children. Veno-occlusive disease causing hepatic

confirmed by cholangiography that shows a characteris- congestion and jaundice may be seen in children in the

tic beading and stenosis of the common or intrahepatic first few weeks following bone marrow transplantation.

bile ducts in the absence of choledocholithiasis.

Clinical Evaluation

AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS Distinguishing between conjugated and unconjugated

Autoimmune hepatitis is a chronic progressive inflamma- hyperbilirubinemia is a most important first step in diag-

tory liver disease of unknown etiology. Two major sub- nosis. Whereas the presence of dark urine, pale stools,

types have been identified based on circulating autoanti- or pruritus in a jaundiced patient suggests hepatobiliary

bodies. Type 1 disease, defined by the presence of anti- disease with a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the ab-

smooth muscle antibodies (ASMAs) and antinuclear sence of these symptoms does not specify the underlying

type of jaundice, and laboratory

studies are required. If the jaun-

dice is associated with abdominal

. . . the acute onset of jaundice in any pain, it is important to document

the nature, site, and severity of the

child may be an initial clinical manifestation pain. Cholecystitis or chole-

of previously unrecognized chronic liver docholithiasis due to gallstone

disease. disease usually presents with se-

vere epigastric or right upper

quadrant pain, often accompanied

by vomiting. For acute viral hepa-

antibodies (ANAs), typically presents in adolescent fe- titis, the abdominal pain characteristically is a dull ache in

males as an acute hepatitis with symptoms of malaise, the right upper quadrant. Personality changes, inappro-

nausea, anorexia, fatigue, abdominal pain, and jaundice. priate behavior, and disturbed sleep-wake cycle or wors-

Type 2 autoimmune liver disease, associated with the ening school performance in a child who has jaundice

liver-kidney microsomal antibody, is a more rapidly pro- may indicate hepatic encephalopathy, suggesting fulmi-

gressive form that usually presents with similar symptoms nant hepatitis, or may represent features of the CNS

in younger children and infants. complications of Wilson disease.

In reviewing the past history, it is important to inquire

HEPATOTOXINS about risk factors for viral hepatitis, such as maternal-

A variety of drugs or environmental agents may be hep- infant transmission, transfusion of contaminated blood

atotoxic and cause jaundice in older children and adoles- products, intravenous drug abuse, high-risk sexual activ-

cents. Acetaminophen overdose is a leading cause of ity, travel history, or a history of infectious contacts.

fulminant hepatic failure in these age groups. Hepato- A detailed review of all medications is essential to search

toxicity develops in the face of glutathione depletion, for potential hepatotoxic agents, especially acetamino-

after which any excess acetaminophen is metabolized phen abuse or misuse. Consanguinity or a family history

by the hepatic P450 pathway to produce the hepato- for jaundice may suggest inherited metabolic conditions

toxic product NAPQI (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine). such as Wilson disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency,

A distinct clinical course ensues, with initial nausea and cystic fibrosis, or Gilbert syndrome.

vomiting, followed progressively by a quiescent period The physical examination should focus on signs of

and acute liver dysfunction with jaundice and coagulopa- chronic liver disease; the acute onset of jaundice in any

thy. Hepatic failure may develop with progressive en- child may be an initial clinical manifestation of previously

cephalopathy and coma. Other hepatotoxic agents that unrecognized chronic liver disease. Pallor may suggest an

Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001 223

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

acute hemolytic anemia or chronic liver disease. Malnu-

trition, palmar erythema, and spider nevi on the chest or Laboratory Evaluation of

Table 3.

upper extremities suggest chronic liver disease. General-

ized lymphadenopathy and pharyngitis point to an EBV

Hyperbilirubinemia in Older

infection. The finding of KF rings on opthalmologic Children

slitlamp examination suggests Wilson disease. The liver

must be carefully palpated and percussed to assess its Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

texture and measure its size and span. The normal liver ● Complete blood count

● Reticulocyte count

span is approximately 9 to 12 cm in early adolescence.

● Blood smear

A nodular hard surface or a shrunken liver suggests ● Serum haptoglobins

cirrhosis. Sharp-edged, tender hepatomegaly typifies ● Direct and indirect Coombs test

acute hepatitis. Splenomegaly may be present because of ● Hemoglobin electrophoresis

a hemolytic disease or acute EBV infection or it may be ● Red cell enzyme assay

● Test for spherocytosis

the singular sign for chronic liver disease with cirrhosis

and portal hypertension. Abdominal distension or shift- Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia

ing dullness on percussion in the flanks may indicate ● Liver function tests (AST, ALT, ALP, and GGT)

ascites formation. Neurologic abnormalities, includ- ● Synthetic liver function (prothrombin time, total

ing confusion and delirium, asterixis, hyperreflexia, or protein, albumin, glucose, cholesterol, ammonia)

decorticate or decerebrate posturing, are all features of ● Abdominal ultrasonography

● HAV IgM, HBsAg, IgM-antiHBcore, antiHCV,

hepatic encephalopathy. Early onset of encephalopathy Monospot姞/EBV titers

in a patient who has newly diagnosed liver disease defines ● Serum ceruloplasmin, 24-hour urinary copper

fulminant liver failure and portends a poor prognosis. excretion

● Serum IgG, autoantibodies (ANA, ASMA, anti-liver-

Laboratory Evaluation and Diagnosis kidney-microsomal antibody)

● Serum alpha-1-antitrypsin level and phenotype

Bilirubin fractionation by the Ektachem or Diazo ● Liver biopsy

method is a necessary first step in the laboratory evalua-

tion of any older child or adolescent who has jaundice

(Table 3). Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in this age albumin. Of these, the most sensitive test for synthetic

group is due most often to hemolytic disease. A complete liver function is the PT. Prolongation of the PT despite

blood count, reticulocyte count, direct and indirect administration of vitamin K suggests significant hepatic

Coombs tests, measurement of serum haptoglobins, and dysfunction. Patients who have acute hepatitis and a

hemoglobin electrophoresis should be requested. Excep- marked coagulopathy that is not responsive to vitamin K

tionally, a Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia may be or who manifest other “worrisome signs” (Table 4)

the sole presenting feature of Wilson disease. In the should be referred promptly to a center that has expertise

absence of hemolysis or elevated liver enzyme levels, in the management of children who have advanced liver

Gilbert syndrome should be considered in the adolescent disease and where liver transplantation is readily avail-

who has mild unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. able. For these more urgent cases, intensive supportive

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia suggests hepatobili- care and liver transplantation hold the greatest potential

ary disease. The initial laboratory investigations should for survival.

include a complete blood count, liver function tests Further laboratory investigations are directed toward

(AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase [ALP], gamma- establishing a diagnosis. Every patient who presents with

glutamyltransferase [GGT]), total protein, serum albu- conjugated hyperbilirubinemia should undergo abdom-

min, and a prothrombin time (PT). Although there is inal ultrasonography to examine the hepatic architecture

considerable overlap, predominant elevation of the AST and to exclude biliary tract disease. Screening for the viral

and ALT suggests hepatocellular injury, and a prevailing hepatitides should include serology for hepatitis A im-

elevation in the ALP and GGT suggests biliary tract munoglobulin M (IgM), hepatitis B surface antigen,

disease. It is important to remember that the so-called IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen, and anti-HCV.

“liver function tests” are a misnomer; they do not reveal A Monospot威 test or serology for EBV is also highly

anything about the synthetic function of the liver. Tests recommended for the adolescent who presents with con-

for liver function include a coagulation screen and mea- jugated hyperbilirubinemia. Measurement of serum

surements of serum glucose, cholesterol, ammonia, and alpha-1-antitrypsin levels and protease inhibitor pheno-

224 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

each individual disease state is beyond the scope of this

“Worrisome” Signs and

Table 4. article. In general, acute hemolytic crises require hyper-

hydration and close monitoring of renal function. Immu-

Symptoms in the Jaundiced nosuppressive agents, such as prednisone, azathioprine,

Older Child or Adolescent who or cyclosporine, are used to treat autoimmune hepatitis.

has Acute Hepatitis Penicillamine is the drug of choice for Wilson disease,

although zinc replacement and trientine also have been

● Onset of hepatic encephalopathy prescribed. N-acetyl-cysteine is recommended for the

● Vitamin K-resistant prolongation of the prothrombin treatment of acetaminophen overdose. Patients who

time have acute viral hepatitis, especially hepatitis A, are prone

● Cerebral edema

to dehydration and require adequate fluid support.

● Serum bilirubin 18 mg/dL (>300 mcmol/L)

● Rising serum bilirubin with decreasing ALT/AST Passive immunoprophylaxis should be administered to

● Rising serum creatinine all close family contacts of patients who have acute

● Hypoglycemia hepatitis A.

● Sepsis Any child who has conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and

● Ascites

encephalopathy or biochemical features of hepatic syn-

● pH<7.3 in acetaminophen overdose

thetic dysfunction, best evidenced by a prolonged PT, is

at high risk to develop a more fulminant course that has

typing should be requested to exclude alpha-1- a fatal outcome. Close supervision and intensive support-

antitrypsin deficiency. Patients who have autoimmune ive care are required, preferably by physicians who have

hepatitis, jaundice, and an elevated ALT usually exhibit expertise in the management of advanced pediatric liver

a high serum total protein relative to the albumin, re- disease.

flecting an increased globulin fraction. This is a result of

the significant hypergammaglobulinemia often found Summary

in association with autoimmune hepatitis. Aside from The spectrum of diseases causing jaundice in older chil-

measuring the serum IgG, other tests for autoimmune dren and adolescents differs from that in the neonate and

hepatitis should include an ANA, ASMA, and anti-liver- young infant. A sound knowledge of the differential

kidney-microsomal antibody. A liver biopsy is recom- diagnosis of unconjugated and conjugated hyperbiliru-

mended to confirm the diagnosis. binemia in this age group provides the framework for a

Serum ceruloplasmin is a valuable screening test for sensible approach to the clinical evaluation and labora-

Wilson disease. A decreased serum ceruloplasmin level is tory investigation of these children. For patients who

found in up to 80% of affected patients. Another useful have acute hepatitis, a careful assessment of liver function

diagnostic test is the 24-hour urinary copper excretion. is of critical importance. Signs and symptoms of liver

In Wilson disease, the urinary copper excretion is typi- dysfunction in a jaundiced patient should prompt an

cally greater than 100 mcg/24 h. Serum copper levels are immediate referral to a tertiary center where expertise in

not helpful in diagnosing Wilson disease except for those the management of pediatric liver disease and hepatic

rare patients presenting with fulminant liver failure, in transplantation is readily available.

whom serum copper levels are significantly elevated.

Other laboratory abnormalities often seen in Wilson

disease include a low serum ALP, particularly when ful- Suggested Reading

minant hepatic failure is present, and low serum phos- D’Agata ID, Balistreri WF. Evaluation of liver disease in the pedi-

atric patient. Pediatr Rev. 1999;20:376 –389

phate and uric acid due to the associated Fanconi syn-

Gourley GR. Disorders of bilirubin metabolism. In: Suchy F, ed.

drome. Quantification of hepatic copper concentration Liver Disease in Children. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1994:

in a liver biopsy tissue specimen (⬎250 mcg/g of dry 401– 413

weight liver) remains the gold standard for diagnosing Jonas M. Viral hepatitis. In: Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR,

Wilson disease. Walker-Smith JA, Watkins JB, eds. Pediatric Gastrointestinal

Disease. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1996:1028 –1051

Mews C, Sinatra F. Chronic liver disease in children. Pediatr Rev.

Treatment 1993;14:436 – 443

Specific treatment of the hyperbilirubinemia depends on Roberts EA, Cox DW. Wilson disease. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol.

the precise etiology. A detailed discussion of therapy for 1998:12:237–256

Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001 225

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

gastroenterology jaundice in children

PIR Quiz

Quiz also available online at www.pedsinreview.org.

1. You are seeing a 13-year-old girl who has acute onset of jaundice. She previously has been healthy, but

had a mild viral illness 1 week ago. She appears well and has mild scleral icterus. Laboratory testing reveals

a total bilirubin of 4 mg/dL (68.4 mcmol/L) that is all unconjugated. There is no evidence of hemolysis on a

peripheral smear. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Autoimmune hepatitis.

B. Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

C. Gilbert syndrome.

D. Hepatitis A.

E. Wilson disease.

2. A 10-year-old boy comes to your office with a 4-day history of abdominal pain, nausea, and jaundice.

He appears mildly ill and is notably jaundiced. His laboratory values are as follows: conjugated bilirubin,

10.5 mg/dL (179.6 mcmol/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 800 U/L; and alanine aminotransferase, 950 U/L.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency.

B. Cholelithiasis.

C. Epstein-Barr virus infection.

D. Hepatitis A.

E. Hepatitis B.

3. Which of the following statements about Wilson disease in adolescents is true?

A. Central nervous system symptoms are always present with hepatic insufficiency.

B. Elevated serum copper levels are pathognomonic of the disease.

C. Kayser-Fleischer rings are almost always present with neurologic involvement.

D. Patients typically are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.

E. The gold standard for diagnosis is an elevated ceruloplasmin level.

4. Which of the following laboratory tests is the most sensitive indicator of liver function?

A. Alanine aminotransferase.

B. Albumin.

C. Alkaline phosphatase.

D. Prothrombin time.

E. Total bilirubin level.

5. You are evaluating a 15-year-old patient who has had a 2-week history of worsening jaundice. She shows

signs of depression. You are concerned about the possibility of fulminant liver failure. Which of the

following is most likely to prompt you to refer her to a liver transplant center immediately?

A. Increasing conjugated bilirubin and liver enzyme levels.

B. Persistently elevated prothrombin time despite administration of vitamin K.

C. Presence of ascites.

D. Presence of splenomegaly.

E. Rising levels of ammonia.

226 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.7 July 2001

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

Jaundice in Older Children and Adolescents

Dinesh Pashankar and Richard A. Schreiber

Pediatrics in Review 2001;22;219

DOI: 10.1542/pir.22-7-219

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/22/7/219

Supplementary Material Supplementary material can be found at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2001/06/27/22.

7.219.DC1

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2005/01/27/22.

7.219.DC2

References This article cites 3 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/22/7/219.full#ref-list

-1

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Fetus/Newborn Infant

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/fetus:n

ewborn_infant_sub

Hyperbilirubinemia

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/hyperbi

lirubinemia_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

https://shop.aap.org/licensing-permissions/

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/reprints

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

Jaundice in Older Children and Adolescents

Dinesh Pashankar and Richard A. Schreiber

Pediatrics in Review 2001;22;219

DOI: 10.1542/pir.22-7-219

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/22/7/219

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca,

Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2001 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved.

Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by 1476414 on May 11, 2019

You might also like

- Jaundice: in Older Children and AdolescentsDocument10 pagesJaundice: in Older Children and AdolescentsjoslinmtggmailcomNo ratings yet

- Jaundice in The Adult PatientDocument6 pagesJaundice in The Adult Patientrbatjun576No ratings yet

- Jaundice Newborn - 2Document15 pagesJaundice Newborn - 2Miratunnisa AzzahrahNo ratings yet

- Jaundice: Newborn To Age 2 Months: Education GapDocument14 pagesJaundice: Newborn To Age 2 Months: Education GapRaul VillacresNo ratings yet

- Liver DiseasesDocument10 pagesLiver DiseasesDaniel HikaNo ratings yet

- Conjugated Hyperbilirubinemia:: Screening and Treatment in Older Infants and ChildrenDocument11 pagesConjugated Hyperbilirubinemia:: Screening and Treatment in Older Infants and ChildrendjebrutNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Indirect HyperbilirubinemiaDocument14 pagesNeonatal Indirect HyperbilirubinemiaValen CadenaNo ratings yet

- Hiperbilirrubinemia DirectaDocument9 pagesHiperbilirrubinemia DirectaRonal Cadillo MedinaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Jaundice in Adults: Patient InformationDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Jaundice in Adults: Patient InformationCarlos CalvacheNo ratings yet

- Clase 3 HepatogramaDocument9 pagesClase 3 HepatogramajuanpbagurNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics in Review33 (7) 291Document14 pagesPediatrics in Review33 (7) 291Barbara Helen Stanley100% (1)

- Neonatal Jaundice: Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Current Issues in Neonatal CareDocument6 pagesNeonatal Jaundice: Aetiology, Diagnosis and Treatment: Current Issues in Neonatal CareLaila AzizahNo ratings yet

- Jaundice Clinical Manifestation and Pathophysiology A Review ArticleDocument3 pagesJaundice Clinical Manifestation and Pathophysiology A Review ArticleHany ZutanNo ratings yet

- Neonatal JaundiceDocument48 pagesNeonatal JaundiceRemy MartinsNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch ProposalZablon KodilaNo ratings yet

- Core Concepts Bilirrubin MetabolismDocument9 pagesCore Concepts Bilirrubin MetabolismAngelina ChunNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Jaundice Bilirubin Physiology and ClinicaDocument13 pagesNeonatal Jaundice Bilirubin Physiology and ClinicaNURUL NADIA BINTI MOHD NAZIR / UPMNo ratings yet

- Nej M 200102223440807Document10 pagesNej M 200102223440807fajriNo ratings yet

- Health Education On NEONATAL JAUNDICEDocument23 pagesHealth Education On NEONATAL JAUNDICEAsha jilu100% (2)

- Daftar-IsiDocument2 pagesDaftar-Isi'RahmaT' ANdesjer Lcgs CuyyNo ratings yet

- HyperbilirubinemiaDocument48 pagesHyperbilirubinemiaEdrik Luke Pialago100% (2)

- 1 Core Concepts Bilirubin MetabolismDocument9 pages1 Core Concepts Bilirubin Metabolismlink0105No ratings yet

- Neonatal JaundiceDocument4 pagesNeonatal JaundiceChristian Eduard de DiosNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Jaundice Cme 3Document56 pagesNeonatal Jaundice Cme 3Arief NorddinNo ratings yet

- Newborn Jaundice Guide: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocument5 pagesNewborn Jaundice Guide: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentArinaManaSikanaNo ratings yet

- Monorafia SP BryanDocument45 pagesMonorafia SP BryanBryan SanchezNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Anemia: Revisiting The Enigmatic PyknocyteDocument5 pagesNeonatal Anemia: Revisiting The Enigmatic PyknocyteDavid MerchánNo ratings yet

- Jaundice - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument11 pagesJaundice - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfCONSTANTIUS AUGUSTONo ratings yet

- Managing Breast Milk JaundiceDocument7 pagesManaging Breast Milk JaundiceJéssica MorenoNo ratings yet

- Liver Chemistry and Function Tests: Daniel S. PrattDocument11 pagesLiver Chemistry and Function Tests: Daniel S. PrattAnişoara FrunzeNo ratings yet

- Final Jaundice1Document43 pagesFinal Jaundice1ahmad solehinNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia: Mahlet Abayneh Assistant Professor of PediatricsDocument41 pagesNeonatal Hyperbilirubinemia: Mahlet Abayneh Assistant Professor of PediatricsBegashawNo ratings yet

- Applied Physiology of Bilirubin MetabolismDocument6 pagesApplied Physiology of Bilirubin MetabolismRenata SetyariantikaNo ratings yet

- Oj 2 PDFDocument6 pagesOj 2 PDFAnisah Maryam DianahNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia and JaundiceDocument8 pagesNeonatal Hyperbilirubinemia and JaundiceAndreea GeorgianaNo ratings yet

- PathologyDocument19 pagesPathologyAfrin AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Assessment of jaundice causes and evaluationDocument16 pagesAssessment of jaundice causes and evaluationlaura canoNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics - Neonatal Jaundice PDFDocument2 pagesPediatrics - Neonatal Jaundice PDFJasmine KangNo ratings yet

- Bac GroundDocument6 pagesBac GroundRitu Ayu PutriNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Jaundice: Understanding and Preventing KernicterusDocument12 pagesNeonatal Jaundice: Understanding and Preventing Kernicterusn_akash3977No ratings yet

- Core Concepts:: Bilirubin MetabolismDocument9 pagesCore Concepts:: Bilirubin MetabolismManasye AlanNo ratings yet

- TAYLOR 1984 AnaesthesiaDocument3 pagesTAYLOR 1984 Anaesthesiapolly91No ratings yet

- Peadiatrics Assignment - Mr. KangwaDocument11 pagesPeadiatrics Assignment - Mr. KangwaTahpehs PhiriNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Jaundice 2023Document31 pagesNeonatal Jaundice 2023Demelash SolomonNo ratings yet

- PPPPDocument6 pagesPPPPChristy Ada IjeomaNo ratings yet

- HyperbilirubinemiaDocument10 pagesHyperbilirubinemiachiboogs456100% (1)

- J Mpsur 2017 09 012Document7 pagesJ Mpsur 2017 09 012riffarsyad100% (1)

- Jaundice and Ascites Group ProjectDocument15 pagesJaundice and Ascites Group ProjectJosiah Noella BrizNo ratings yet

- Jaundice 160318164012Document47 pagesJaundice 160318164012Ritik MishraNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Managing Breast Milk JaundiceDocument7 pagesUnderstanding and Managing Breast Milk JaundiceJulian RiveraNo ratings yet

- Hyperbilirubinemia: West Visayas State University College of Medicine Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDocument49 pagesHyperbilirubinemia: West Visayas State University College of Medicine Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDonna LabaniegoNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Jaundice: Bilirubin MetabolismDocument2 pagesNeonatal Jaundice: Bilirubin MetabolismghsNo ratings yet

- 73 Liver Chemistry and Function TestsDocument11 pages73 Liver Chemistry and Function TestsPaola PizanoNo ratings yet

- IctericiaDocument19 pagesIctericiadavid pinedaNo ratings yet

- T15 - Neonatal JaundiceDocument38 pagesT15 - Neonatal JaundiceMawuliNo ratings yet

- ) Jaundice PDFDocument4 pages) Jaundice PDFAzzNo ratings yet

- 10 NNJ 1Document22 pages10 NNJ 1ahmed shorshNo ratings yet

- Nelson JaundiceDocument7 pagesNelson JaundiceJesly CharliesNo ratings yet

- Liver Disorders in Childhood: Postgraduate Paediatrics SeriesFrom EverandLiver Disorders in Childhood: Postgraduate Paediatrics SeriesNo ratings yet

- Metabolism With Triphasic Oral Contraceptive Formulations Containing Norgestimate or LevonorgestrelDocument6 pagesMetabolism With Triphasic Oral Contraceptive Formulations Containing Norgestimate or LevonorgestrelhectorNo ratings yet

- English LessonDocument2 pagesEnglish LessonhectorNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Medical Education PodcastsDocument25 pagesComprehensive Medical Education PodcastshectorNo ratings yet

- Endocrinology In-Training ObjectivesDocument12 pagesEndocrinology In-Training ObjectiveshectorNo ratings yet

- Sample Diabetic Ketoacidosis (Dka) Clinical Order Set: AdultDocument2 pagesSample Diabetic Ketoacidosis (Dka) Clinical Order Set: AdulthectorNo ratings yet

- U.S. Contraceptive Use Recommendations 2016Document60 pagesU.S. Contraceptive Use Recommendations 2016hectorNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Three Methods of Contraception: Effects On Blood Glucose and Serum Lipid ProfilesDocument4 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Three Methods of Contraception: Effects On Blood Glucose and Serum Lipid ProfileshectorNo ratings yet

- Blood Pressure Log 02Document1 pageBlood Pressure Log 02hectorNo ratings yet

- 60 Affirmations For PeaceDocument21 pages60 Affirmations For PeacehectorNo ratings yet

- Example Abstract ItemDocument2 pagesExample Abstract ItemhectorNo ratings yet

- Glasgow Coma Scale (With Explanations)Document1 pageGlasgow Coma Scale (With Explanations)hectorNo ratings yet

- Gauthier 1992Document6 pagesGauthier 1992hectorNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning Guide FormDocument3 pagesClinical Reasoning Guide FormhectorNo ratings yet

- Mental Status ExamDocument4 pagesMental Status Examscootaccess100% (1)

- Internal Medicine Progress Note TemplateDocument2 pagesInternal Medicine Progress Note Templatehector100% (1)

- ACGMECLERNational Report Findings 2019Document132 pagesACGMECLERNational Report Findings 2019hectorNo ratings yet

- Paradigm Shift - Gratitude PadDocument1 pageParadigm Shift - Gratitude PadElmer GarchitorenaNo ratings yet

- GYN History Physical PDFDocument2 pagesGYN History Physical PDFMariam A. KarimNo ratings yet

- Assignments Report - Surgery ProgramsDocument16 pagesAssignments Report - Surgery ProgramshectorNo ratings yet

- Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) : Content Description and General InformationDocument12 pagesStep 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) : Content Description and General InformationAleezay ZaharaNo ratings yet

- AOAStudy 2018Document26 pagesAOAStudy 2018Gerardo Lerma100% (1)

- Soapwhat To WriteDocument1 pageSoapwhat To WriteJoriza TamayoNo ratings yet

- Leadership PlenaryDocument1 pageLeadership PlenaryhectorNo ratings yet

- SketchyIM Check List PDFDocument5 pagesSketchyIM Check List PDFhectorNo ratings yet

- Example Note 1Document2 pagesExample Note 1naimNo ratings yet

- Serenity Tri-Fold PDFDocument2 pagesSerenity Tri-Fold PDFFynneganNo ratings yet

- NBME Subject Exam Content Outlines and Sample ItemsDocument144 pagesNBME Subject Exam Content Outlines and Sample ItemshectorNo ratings yet

- CS Blue Sheet Mnemonics - USMLE Step 2 CS - WWW - MedicalDocument1 pageCS Blue Sheet Mnemonics - USMLE Step 2 CS - WWW - MedicalRavi Parhar75% (4)

- The AOA Guide:: How To Succeed in The Third-Year ClerkshipsDocument25 pagesThe AOA Guide:: How To Succeed in The Third-Year Clerkshipshector100% (1)

- Primer2ndEd PDFDocument37 pagesPrimer2ndEd PDFhectorNo ratings yet

- ECHO MASTERCLASS: A GUIDE TO ACCURATELY ASSESSING HEART VALVE DISEASEDocument136 pagesECHO MASTERCLASS: A GUIDE TO ACCURATELY ASSESSING HEART VALVE DISEASEVladlena Cucoș-CaraimanNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Public Health NursingDocument37 pagesIntroduction to Public Health NursingKailash NagarNo ratings yet

- Stool Exam Guide - Key Tests, Colors, Consistencies in 40 CharactersDocument8 pagesStool Exam Guide - Key Tests, Colors, Consistencies in 40 CharactersLester John HilarioNo ratings yet

- Vegetable Kingdom Continued: SciaticDocument14 pagesVegetable Kingdom Continued: SciaticSatyendra RawatNo ratings yet

- Thyroid DiseasesDocument44 pagesThyroid DiseasesPLDT HOMENo ratings yet

- Osteoporosis Clinical Case by SlidesgoDocument30 pagesOsteoporosis Clinical Case by SlidesgoHussein Al-jmrawiNo ratings yet

- General Stress Level of SHS ABM Students in Their Specialized SubjectDocument4 pagesGeneral Stress Level of SHS ABM Students in Their Specialized SubjectThons Nacu LisingNo ratings yet

- Philippine College of Physicians Daily Census Ward Hospital de Los Santos-Sti Medical CenterDocument22 pagesPhilippine College of Physicians Daily Census Ward Hospital de Los Santos-Sti Medical Centercruz_johnraymondNo ratings yet

- HematologyDocument6 pagesHematologyRian CopperNo ratings yet

- Antenatal CareDocument12 pagesAntenatal CarefiramnNo ratings yet

- PhenobarbitalDocument2 pagesPhenobarbitalhahahahaaaaaaaNo ratings yet

- CV Abdul HafeezDocument7 pagesCV Abdul HafeezAbdul Hafeez KandhroNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Pharmacology For Nurses A Pathophysiologic Approach 5th EditionDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Pharmacology For Nurses A Pathophysiologic Approach 5th Editiontipsterchegoe.t8rlzv100% (41)

- Questions from the Ministry of Health for Residency and Fellowship Programs (2013-2018Document68 pagesQuestions from the Ministry of Health for Residency and Fellowship Programs (2013-2018Ahmad HamdanNo ratings yet

- Daftar Harga Ethical Per April'22 (Khus Riau)Document8 pagesDaftar Harga Ethical Per April'22 (Khus Riau)iraNo ratings yet

- Guide For History Taking, Physical Exam and Diagnosis of Pediatric PatientsDocument19 pagesGuide For History Taking, Physical Exam and Diagnosis of Pediatric PatientsKendall Marie BuenavistaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Airway for Difficult Intubation (LEMON MethodDocument7 pagesEvaluating The Airway for Difficult Intubation (LEMON Methodtri-edge 8No ratings yet

- The Heart, Part 1 - Under Pressure: Crash Course A&P # 25Document5 pagesThe Heart, Part 1 - Under Pressure: Crash Course A&P # 25Jordan TorresNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Two Brazilian Quilombola Communities in Southwest Bahia StateDocument7 pagesPrevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Two Brazilian Quilombola Communities in Southwest Bahia StateIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Movement Disorders Types - Mayo ClinicDocument1 pageMovement Disorders Types - Mayo ClinicdrrajmptnNo ratings yet

- Cues Nursing Diagnosis Goal Nursing Interventions Rationale EvaluationDocument3 pagesCues Nursing Diagnosis Goal Nursing Interventions Rationale EvaluationVher SisonNo ratings yet

- Tracheo-Oesophageal FistulaDocument23 pagesTracheo-Oesophageal FistulaAhmad KhanNo ratings yet

- EMR Implementation Readiness Assessment and Patient Satisfaction ReportDocument20 pagesEMR Implementation Readiness Assessment and Patient Satisfaction ReportAbidi HichemNo ratings yet

- Pathologt of The HeartDocument40 pagesPathologt of The HeartJudithNo ratings yet

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia - BPH - Pathophysiology - Schematic DiagramDocument2 pagesBenign Prostatic Hyperplasia - BPH - Pathophysiology - Schematic DiagramSimran JosanNo ratings yet

- Free Modern Neuromuscular Techniques PDFDocument6 pagesFree Modern Neuromuscular Techniques PDFStiven FloresNo ratings yet

- Food Poisoning and IntoxicationsDocument26 pagesFood Poisoning and IntoxicationslakshmijayasriNo ratings yet

- PREBORD NLE8part1Document671 pagesPREBORD NLE8part1Bryan NorwayneNo ratings yet

- REBOZETDocument28 pagesREBOZETAndronikus DharmawanNo ratings yet

- L5 - Nature of Clinical Lab - PMLS1Document98 pagesL5 - Nature of Clinical Lab - PMLS1John Daniel AriasNo ratings yet