Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How To Build A Light-Controlled Mixer

Uploaded by

SeoolasOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How To Build A Light-Controlled Mixer

Uploaded by

SeoolasCopyright:

Available Formats

diy

how to build a

light-controlled mixer

go to the dark side and start controlling sound!

by rob cruickshank

photography by adam coish

G

estural control is a hot

topic these days. A bit of search-

ing on the Internet will turn

up all sorts of projects that can

turn hand waving into sound, using accel-

erometers, cameras, or Microsoft’s Kinect

controller. But did you know that for only

a few dollars you can make a hands-free

controller that uses no computers, chips, or

even batteries? It’s a simple passive circuit,

based on light-dependent resistors, that will

mix two audio signals, based on the amount

of light falling on its sensors. Not so hi-tech,

but definitely gestural.

Our circuit is a simple passive mixer—a

primitive ancestor of the larger, more sophis-

ticated mixers you may be familiar with, used

in recording and PA applications. Instead of

knobs or sliders, however, our mixer will use

four photocells. These are components that

change their resistance with the amount of

light falling on them. Our circuit will be wired

so that increasing the light on the sensor will

decrease the amount of audio passing through

the circuit. You might want to think of this as

a dark-controlled mixer.

This circuit was inspired by the Lowell

Cross’ design for the chessboard used in

the 1968 performance Reunion, featuring

John Cage and Marcel Duchamp. For more

on that, see Cross’ article “Reunion: John

Cage, Marcel Duchamp, Electronic Music

and Chess” in the December 1999 issue of the

Leonardo Music Journal.

We’ll show the mixer as mixing two stereo

(two-channel) inputs down to one stereo

output, but you can also build it to mix four

mono sources to one mono output.

46 musıcworks #111 | winter 2011

set up

A B

materials

[A] 1 small plastic project box (available

from any electronics supplier) in

which to house the mixer

[B] 2 audio cables, each with a 3.5 mm stereo

miniplug on one end, and a pair of male

RCA connectors on the other end

[C] Rosin-core electronics solder

(consider using the lead-free variety)

[D] Insulated hookup wire, 22 gauge,

solid-core (you’ll need about a metre) C D E

[E] 1 piece of circuit board sized to fit the

project box, [A]

[F] 8 10k-ohm resistors coded with three

bars—brown, black, and orange

[G] 4 matching light-dependent resistors

(LDRs), also known as photocells,

photo resistors, or cadmium sulphide

F G

(CdS) cells

tools (not pictured)

Soldering iron with small tip, 40 watts or less Masking tape materials sources

Small wire cutters Ruler marked in inches

and millimetres Light-dependent resistors are sometimes hard to

Wire strippers suitable for

wire gauges from 26 to 20 find. Look for ones with a light resistance in the low

Drill, with a series of hundreds of ohms, and a dark resistance of at least

Needle-nose pliers drill bits 1/16 to 1/4 inch

several-hundred-kilo ohms. The low value for the

Safety glasses or goggles Glue gun with glue sticks light resistance is the most critical value to look for.

We used part number OPTRE-000007 from Creatron

Indelible-ink marker Small screwdriver electronics, <www.creatroninc.com>. Part number

CDS from Solarbotics, <www.solarbotics.com>,

would also work well.

what you need to know before beginning If you live in a large city, you will have more options

for buying parts and tools. Dedicated electronics

retailers:

how to solder Active Tech in major cities across Canada,

There is a good collection of soldering resources on the Website of <www.active123.com>

Limor Fried, an engineer and artist who makes and sells electronic kits, Creatron in Toronto,

<www.ladyada.net/learn/soldering/thm.html>. Also see <www.creatroninc.com>

<www.youtube.com/watch?v=I_NU2ruzyc4&feature=player_embedded>. Addison in Montreal,

<www.addison-electronique.com>

how to work with a circuit board

A page specifically about circuit-board techniques, as used in this project, can These are excellent online sources:

be found at <itp.nyu.edu/physcomp/Tutorials/SolderingAPerfBoard>. Digi-Key, <www.digikey.com>

An excellent book for electronics beginners is Make: Electronics, from Mouser Electronics, <www.mouser.com>

O’Reilly media, <oreilly.com/catalog/9780596153755>. ISBN: 0596153750

winter 2011 | musıcworks #111 47

make it

time required: one hour complexity: moderate cost: five dollars

what you need to know: how to solder, plus basic electronic construction

techniques—and you need to be comfortable using a power drill and a glue gun

1

1c. Use hookup wire to solder connections 1e. Solder a connection between the adjacent

wire up the between the lower leads of all the LDRs, as leads of one set of paired resistors.

circuit shown. NOTE: This will become the common

ground point of the circuit.

1a. Install the LDRs on the circuit board,

arranging them horizontally so that the leads

are oriented vertically, and space them out so

that you can control them individually. NOTE:

The LDRs do not have polarity, and so can be

installed either way.

1d. Solder a pair of 10k-ohm resistors beside

each LDR, as shown.

NOTE: Because you will be mounting the

project in a box, you need to count the number

of holes in the circuit board between the LDRs

in order to determine the spacing of the holes

you’ll drill into the box. The holes in the board 2-to-1 light-controlled mixer

are 0.1 inch apart, so it is best to leave four

holes between each LDR, and then space the

holes in the project box half an inch apart.

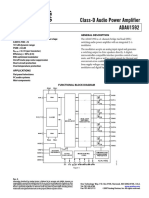

circuit schematic

1b. Use the wire cutters to clip the leads close

to the solder.

winter 2011 | musıcworks #111 49

1f. Use the free end of the hookup wire to i. Place a piece of masking tape lengthwise

solder the connection made in 1e to the free down the centre of the project box lid, on

lead of its adjacent LDR. the inside of which you will be mounting the

mixer.

ii. Use the placement of the centre of

each LDR on the circuit board and the

measurements made in step 1a to locate the

correct position of each LDR hole on the

project box that will become your mixer box.

iii. Use an indelible marker to indicate the

position of each hole.

iii. Remove the masking tape.

2c. Mark on the project box the placement of

the hole for the audio output.

1g. Repeat steps 1e and 1f with each set of i. Place a piece of masking tape along the

paired resistors and each LDR. centre line on the long edges of the project

box’s side.

ii. Use an indelible marker and ruler to

indicate the centre on both sides of the

project box.

2b. Make the holes in the project box at the

NOTE: Looking at the board, consider the

point where the light sensors will go.

LDRs to be numbered left to right, 1, 2, 3, and 4.

i. Use the 1/16-inch drill bit to drill pilot

OUTPUT SIDE holes in the project box at all the marked

R3 R4 R7 R8 LDR locations. 2d. Make the hole in the project box for the

audio output.

R1 R2 R5 R6 i. Use the 1/16-inch drill bit to drill a pilot

hole on the project box’s side for the

output cable.

LDR 1 LDR 2 LDR 3 LDR 4

INPUT SIDE

ii. Gradually increase the size of your drill

2 prepare the

mixer box

2a. Mark on the project box the placement of

bit until the diameter of each hole is slightly

larger than the diameter of each photocell.

NOTE: Don’t be tempted to go straight

to the largest size, because the drill bit

may grab the plastic, ruining the hole, and

the holes for the light sensors. possibly causing injury.

50 musıcworks #111 | winter 2011

ii. Gradually increase the size of your drill 3b. Strip and tin the wire ends of the audio

bit until the diameter of the hole is the same cables. GLOSSARY

as the diameter of the output cable.

i. Use wire strippers to remove 2 cm of the Cadmium Sulphide. A chemical

outer jacket on the free end of one of the compound used in making light-

audio cables. dependent resistors.

Circuit Board. A board, usually

fiberglass, perforated with holes to

mount components in.

Ground. The common point in a

circuit, where all signals return.

Kilo. A prefix meaning 1000. One kilo

2e. Follow the drilling procedure in 2d to ohm, usually written 1kohm, or 1 kΩ, is

make two holes on the opposite side of the 1000 ohms.

project box, each hole to be one half inch on

either side of the centre. Leads. Pronounced leeds. The

wires protruding from an electronic

component such as a resistor.

Light-dependent Resistor. A resistor

which changes its resistance with the

amount of light falling on it.

ii. Twist together the shield wires.

Miniplug. A 1/8-inch (3.5 mm) audio

connector most commonly used with

portable headphones.

Mixer. A device for combining audio

signals.

3

Ohm. A unit of electrical resistance,

connect the named after Georg Ohm.

audio inputs and Ω. The Greek letter omega, used as a

output to the circuit symbol for ohms.

Photocell. A light-sensitive electronic

3a. Use the wire cutters to cut the two audio iii. Use solder to tin the exposed shield component, usually a light-dependent

cables in half. wires. resistor.

Project Box. An inexpensive plastic

enclosure designed to hold an

electronic circuit.

RCA Connector. A small connector,

also known as a phono connector,

invented by the Radio Corporation

of America, and often used in home

audio.

Resistor. A device that limits

NOTE: The two ends with 3.5 mm plugs will iv. Use wire strippers to remove 5 mm of electrical current.

connect to the circuit’s inputs, and one of insulation from the centre audio conductor.

the ends with a pair of RCA connectors will NOTE: This is usually a fine 28-gauge Shield. The outer wires in an audio

connect to the output side. Save the other one conductor, so take care not to cut it. cable, which surround the centre

for future projects. conductor, and are connected to the

common ground.

Tin. The action of coating a conductor

(usually copper) with solder to

facilitate ease in soldering. Note that

hookup wire is often pre-tinned.

Wire Gauge. A system for specifying

wire sizes. Smaller diameter wires

have larger gauge numbers.

winter 2011 | musıcworks #111 51

v. Use solder to tin the centre conductor, 3e. Use hookup wire to connect each of the

making sure not to use too much heat, audio cables’ shield wires to the common troubleshooting

which can melt the insulation. ground point created in step 1c.

1. If a channel is missing entirely

• Check the connections between the

audio cables and resistors.

• Check both input and output

connections.

• Check the connection between

resistors on each channel, e.g., the

connection between R1 and R3.

vi. Repeat steps i to v five times with the • Make sure that there are no

remaining audio cables.

electrical short circuits between the

centre conductor and the shield.

2. If the channel is present, but does

not drop out when light hits the LDR

3f. Wire up the input side of the circuit. NOTE: • Check the connections between the

Please refer to labelled image on pg 50, step 1g.

resistors and the LDR.

i. Use hookup wire to make a connection • Check the connections between the

between the left audio channel of the first LDR and the common ground.

audio input cable to the free end of the

resistor associated with LDR1: R1. NOTE: This is not a perfect mixer. You

will always get a little bleed-through

3c. Feed the cut ends of the input cables and ii. Use hookup wire to make a connection between channels, even in bright light,

between the right audio channel (usually and the balance between channels

output cables through the holes made for

indicated by a red conductor) of the first

them. NOTE: Be aware that once the cables may not be accurate.

are soldered to the board, you will not be able audio input cable to the free end of the

to separate the circuit from the box without resistor associated with LDR2: R4.

unsoldering the cables. ii. Use hookup wire to make a connection

iii. Use hookup wire to make a connection

between the left audio channel of the between the right audio channel of the

second audio input cable to the free end of audio output cable to the junction of

the resistor associated with LDR3: R5. resistors R4 and R8.

iv. Use hookup wire to make a connection iii. Use hookup wire to connect the free ends

between the right audio channel of the of the output resistors R3 and R7. NOTE: This

second audio input cable to the free end of connection allows the individual left signals to

be mixed down to the master left channel.

the resistor associated with LDR4: R6.

iv. Use hookup wire to make a connection

between the left audio channel of the audio

output cable to the junction of resistors R3

3d. Solder each of the audio cables to the and R7.

circuit board—audio inputs on one side of the

circuit and the audio output on the other side

of the circuit. NOTE: The centre conductor

and the shield should be soldered into holes

in the board with one or two holes between

them, taking care that they cannot short

together if the cable is flexed.

3g. Wire up the output side of the circuit.

NOTE: Please refer to labelled image on pg 50,

step 1g.

i. Use hookup wire to connect the free ends

of the output resistors R4 and R8. NOTE: This

connection allows the individual right signals

to be mixed down to the master right channel.

52 musıcworks #111 | winter 2011

4 mount the circuit

in the project box

4a. Use hot glue to secure the circuit board to

use it

the top side of the enclosure in such a way that

the LDRs line up with the appropriate holes.

There are many ways to use the

mixer. Some suggestions are:

Use light to fade between two stereo sources.

Use four completely separate audio signals

in, and use a flashlight to make a real-time

composition.

Make an audio installation that adjusts

audio with the amount of daylight falling on

the sensors.

4b. Use hot glue to secure the cables in place, Because the mixer is completely passive,

so that they don’t get yanked out of the board. it will work as well backwards as forwards!

Try routing a stereo source to two pairs of

powered speakers (you may need some audio

adaptors for this).

Rob Cruickshank is a Toronto-based

multidisciplinary artist.

how it works

5 testing

The circuit works best in bright light, such as

sunlight. A battery-powered flashlight works

well. Fluorescent lights and AC-powered LED voltage divider,

lights might introduce objectionable hum into circuit schematic

the circuit.

5a. Connect the 3.5 mm stereo plugs to two

audio sources, such as MP3 players or laptop

computers.

5b. Connect the RCA plugs to the left and a mixer is a special case of a basic circuit called a voltage divider. A voltage divider takes

right inputs of an amplifier. a voltage source (in our case, an audio signal) and splits it up between two resistors. If one

resistor has a higher resistance (measured in ohms) than the other, it will get a proportionately

5c. Cover each LDR with a small opaque piece higher share of the signal. A resistor that is more than ten times the value of the other resistor

of cardboard. You should hear the audio from will get essentially all of the signal.

both sources, mixed together. The converse is also true: a resistor that has less than one tenth of the value of the other

will get less than ten per cent of the signal.

5d. Remove the piece of cardboard from

one of the LDRs. Expose that LDR to a bright It follows that, if we had a resistor whose value we could change from one tenth of the value

light, such as an LED flashlight. You should hear of a fixed resistor, up to ten times the value of that same resistor, we could control our audio

the corresponding audio channel drop out signal all the way from almost nothing to full volume. This is how a volume control, or poten-

of the audio mix. Repeat with the other LDRs, tiometer, works. We can replace the knob in our volume control with a resistor that changes

listening for the other corresponding channels resistance with light, and we thus have a light-controlled volume control. Add two or more of

to drop out of the audio mix. these together, and we have a light controlled mixer.

winter 2011 | musıcworks #111 53

You might also like

- 99 04 Honda OdysseyDocument2,459 pages99 04 Honda OdysseyJose Crespo75% (4)

- DIY Projects For Guitarists - Craig AndertonDocument102 pagesDIY Projects For Guitarists - Craig Andertonrenegroide100% (34)

- Electronics for Artists: Adding Light, Motion, and Sound to Your ArtworkFrom EverandElectronics for Artists: Adding Light, Motion, and Sound to Your ArtworkRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Sound Card Oscilloscope - MakeDocument14 pagesSound Card Oscilloscope - MakezaphossNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic Weapon (USW) Circuit - Homemade Circuit Projects PDFDocument22 pagesUltrasonic Weapon (USW) Circuit - Homemade Circuit Projects PDFLisa ParksNo ratings yet

- Haywired: Pointless (Yet Awesome) Projects for the Electronically InclinedFrom EverandHaywired: Pointless (Yet Awesome) Projects for the Electronically InclinedRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Allen-Bradley PLC Wiring SystemsDocument196 pagesAllen-Bradley PLC Wiring SystemsKiliardt Scmidt100% (3)

- Cad Trion Microphones Revised PDFDocument6 pagesCad Trion Microphones Revised PDFEsteban Bonilla JiménezNo ratings yet

- Nuts Volts - 2014 10Document84 pagesNuts Volts - 2014 10colin37100% (1)

- DIY Lasers Are Irresistibly Dangerous - Gadget Lab - WiredDocument23 pagesDIY Lasers Are Irresistibly Dangerous - Gadget Lab - Wiredazoc8999100% (1)

- Nutsvolts 2013Document84 pagesNutsvolts 2013kgovindrajan100% (1)

- 12Document84 pages12bn_23579No ratings yet

- How To Make A CRT TV Into An OscilloscopeDocument10 pagesHow To Make A CRT TV Into An OscilloscopeNusret YılmazNo ratings yet

- Reed Ghazala Designing 'Circuit-Bent' Instruments: Sound On Sound's August 1999 Feature OnDocument8 pagesReed Ghazala Designing 'Circuit-Bent' Instruments: Sound On Sound's August 1999 Feature OnjfkNo ratings yet

- Make Magazine - Vol 33Document164 pagesMake Magazine - Vol 33Megan Hall100% (3)

- Diy Seismometer: by KjmagneticsDocument8 pagesDiy Seismometer: by KjmagneticsMohamed Gomaa100% (1)

- Nuts and Volts 2013-07Document84 pagesNuts and Volts 2013-07amit281276No ratings yet

- Elektor Electronics USA 2019 - 1-2 PDFDocument116 pagesElektor Electronics USA 2019 - 1-2 PDFLuiz Henrique Ramos100% (2)

- !!!! Signal Integrity Considerations For High Speed Digital HardwareDocument12 pages!!!! Signal Integrity Considerations For High Speed Digital HardwarePredrag PejicNo ratings yet

- A Simple Arduino-Driven Direct Digital Synthesiser Project: Gets Worry It'sDocument4 pagesA Simple Arduino-Driven Direct Digital Synthesiser Project: Gets Worry It'smastelecentro0% (1)

- A Simple DIY SpectrophotometerDocument30 pagesA Simple DIY SpectrophotometerMiguelDelBarrioIglesisas100% (1)

- DirodDocument31 pagesDirodEvaldas StankeviciusNo ratings yet

- Digital Camera Workflow WhitepaperDocument47 pagesDigital Camera Workflow WhitepaperMatheus MelloNo ratings yet

- RC 1977 05Document69 pagesRC 1977 05Jan Pran100% (1)

- 1 History of MicroelectronicsDocument17 pages1 History of MicroelectronicsWaris AminNo ratings yet

- 1002 - EPE Bounty Treasure HunterDocument7 pages1002 - EPE Bounty Treasure HunterLaurentiu IacobNo ratings yet

- Unit IDocument25 pagesUnit IRamarao BNo ratings yet

- Infrared Emitter From CMOS 555 Robot RoomDocument6 pagesInfrared Emitter From CMOS 555 Robot RoomnkimlevnNo ratings yet

- Metal Simple and Powerful Detector - ElettroAmiciDocument6 pagesMetal Simple and Powerful Detector - ElettroAmiciAbdelmalek BaaliNo ratings yet

- What You Need To Know About Bug Zapper CircuitDocument8 pagesWhat You Need To Know About Bug Zapper CircuitjackNo ratings yet

- School of Engineering: "Electronic Spinet - Musical Instrument Using Arduino"Document7 pagesSchool of Engineering: "Electronic Spinet - Musical Instrument Using Arduino"vishwas chandraNo ratings yet

- Modify A Cheap LDC Condenser Microphone - 7 Steps (With Pictures) - InstructablesDocument1 pageModify A Cheap LDC Condenser Microphone - 7 Steps (With Pictures) - Instructablespepe sanchezNo ratings yet

- Assembly Guide: LED Shadow Clock KitDocument68 pagesAssembly Guide: LED Shadow Clock KitsiogNo ratings yet

- Arduino Pulse Oximeter: by Nate and BenDocument20 pagesArduino Pulse Oximeter: by Nate and BenYafi AliNo ratings yet

- Eg Manual v3Document54 pagesEg Manual v3Max EdpNo ratings yet

- Electroluminescent WireDocument8 pagesElectroluminescent Wireconvers3No ratings yet

- Darksensorusingldronbreadboard 150421105301 Conversion Gate02Document14 pagesDarksensorusingldronbreadboard 150421105301 Conversion Gate02rahul sharmaNo ratings yet

- Circuit Board, Circuit Diagram and Circuit BreadboardDocument13 pagesCircuit Board, Circuit Diagram and Circuit BreadboardZamantha Tiangco0% (1)

- 01introduction VLSI TechnologyDocument32 pages01introduction VLSI Technologyanand kumarNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document26 pagesLecture 1Syed Muhammad AliNo ratings yet

- 5 - Chap3bDocument24 pages5 - Chap3bgustav_goodstuff8176No ratings yet

- PCB Drilling Machine PDFDocument32 pagesPCB Drilling Machine PDFJorge EstradaNo ratings yet

- Project Documentation Automatic Night LightDocument5 pagesProject Documentation Automatic Night LightArnel Langomez Remedios100% (1)

- Led Cube 4x4x4: by Bart BrinkmanDocument19 pagesLed Cube 4x4x4: by Bart BrinkmanCesar VaqueraNo ratings yet

- How Transistors Work - HowStuffWorksDocument2 pagesHow Transistors Work - HowStuffWorksAnilkumar KubasadNo ratings yet

- Hacking The Sonos Ikea Symfonisk Into A High Quality Speaker AmpDocument15 pagesHacking The Sonos Ikea Symfonisk Into A High Quality Speaker AmpCostin RaducanuNo ratings yet

- ConnectorsDocument4 pagesConnectorsnoor shaheenNo ratings yet

- What Does Process Size MeanDocument8 pagesWhat Does Process Size MeangopakumargnairNo ratings yet

- Note 01 Intro PDFDocument7 pagesNote 01 Intro PDFchaciNo ratings yet

- Mis 16Document1 pageMis 16api-3761679No ratings yet

- 1 - Introduction To ArduinoDocument82 pages1 - Introduction To ArduinoDaniel PabunaNo ratings yet

- Broken Wire Detector: Construction & WorkingDocument1 pageBroken Wire Detector: Construction & WorkingMiranto WallNo ratings yet

- EncoderDocument5 pagesEncodermd alamin bin SiddiqueNo ratings yet

- Semiconductor Chips NanotechnologyDocument7 pagesSemiconductor Chips NanotechnologyMuhammad HaseebNo ratings yet

- EDN Febrero 2012Document56 pagesEDN Febrero 2012agnithium100% (1)

- DIY Lightning Detector - Circuit 1Document4 pagesDIY Lightning Detector - Circuit 1Jason BakerNo ratings yet

- Safari - Apr g30, 2019 at 9:17 PMDocument1 pageSafari - Apr g30, 2019 at 9:17 PMnatnael demissieNo ratings yet

- Name: Asad Fareed Reg no:Bee-Fa20-005Document3 pagesName: Asad Fareed Reg no:Bee-Fa20-005ASAD FAREEDNo ratings yet

- Open Source Turtle Robot (OSTR) : InstructablesDocument43 pagesOpen Source Turtle Robot (OSTR) : Instructablesjulio arriolaNo ratings yet

- VectrexDocument54 pagesVectrexKarlson2009100% (1)

- CathoderaytubeDocument14 pagesCathoderaytuberameshsmeNo ratings yet

- Singer 20 U ManualDocument40 pagesSinger 20 U Manualjapa_ps67% (6)

- 54810A Service GuideDocument202 pages54810A Service GuideSeoolasNo ratings yet

- Singer 20 U ManualDocument40 pagesSinger 20 U Manualjapa_ps67% (6)

- DIY Instrumentation MicrophoneDocument1 pageDIY Instrumentation MicrophoneSeoolasNo ratings yet

- eROCKIT English Leaflet SmallDocument2 pageseROCKIT English Leaflet SmallSeoolasNo ratings yet

- Triacd Motor ControlerDocument1 pageTriacd Motor ControlerSeoolasNo ratings yet

- Electronic Installation Practices Manual WWDocument152 pagesElectronic Installation Practices Manual WWSeoolasNo ratings yet

- Telephone Instruments and SignalsDocument38 pagesTelephone Instruments and SignalsTeknoz Jadhav100% (1)

- EC214 LAB NewDocument55 pagesEC214 LAB NewzohaibNo ratings yet

- Imagerunner 1750/1740/1730 Series: Service Manual Rev. 3.0Document385 pagesImagerunner 1750/1740/1730 Series: Service Manual Rev. 3.0MY WAY RMNo ratings yet

- Av02 0525en 1Document24 pagesAv02 0525en 1Salvador FayssalNo ratings yet

- Multi-Phase PWM Controller With PWM-VID Reference: General Description FeaturesDocument24 pagesMulti-Phase PWM Controller With PWM-VID Reference: General Description FeaturesSurendra SharmaNo ratings yet

- Dealing With ElectronicsDocument417 pagesDealing With ElectronicsChantuNo ratings yet

- Library RecordsDocument9 pagesLibrary RecordsDr-Atul Kumar DwivediNo ratings yet

- Digital Logic Design BasicsDocument11 pagesDigital Logic Design BasicsGaming PartyNo ratings yet

- Tda 6107 AjfDocument16 pagesTda 6107 AjfHenryAmayaLarrealNo ratings yet

- BJT AC Analysis: Chapter ObjectivesDocument127 pagesBJT AC Analysis: Chapter ObjectivesDONE AND DUSTED100% (1)

- Alternatives To Breadboard: SpringboardDocument3 pagesAlternatives To Breadboard: SpringboardSomesh KshirsagarNo ratings yet

- ADAU1592Document25 pagesADAU1592Aniket SinghNo ratings yet

- Shouding: 1Mhz, 2A Step-Up Current Mode PWM ConverterDocument9 pagesShouding: 1Mhz, 2A Step-Up Current Mode PWM ConverterRicardo PiovanoNo ratings yet

- In A Logic Circuit A Hazard Is Independent FormDocument11 pagesIn A Logic Circuit A Hazard Is Independent Formwin papasanNo ratings yet

- Microprocessor, Microcomputer and Assembly LanguageDocument22 pagesMicroprocessor, Microcomputer and Assembly LanguageAdityaNo ratings yet

- Brown Out CircuitDocument5 pagesBrown Out Circuitsync0931100% (3)

- Power Point Presentation On Infrared Remote Control OnDocument15 pagesPower Point Presentation On Infrared Remote Control OnPallav Das100% (1)

- Littelfuse Capacitance and Signal Integrity Application NoteDocument2 pagesLittelfuse Capacitance and Signal Integrity Application Notesujeet kumarNo ratings yet

- Ugea1323 deDocument2 pagesUgea1323 deTan Li KarNo ratings yet

- Cxa2061S: Y/C/Rgb/D For NTSC Color TvsDocument44 pagesCxa2061S: Y/C/Rgb/D For NTSC Color Tvs6tanksNo ratings yet

- Multichannel IR Remote Control For Home OfficeDocument7 pagesMultichannel IR Remote Control For Home OfficeKamlesh Motghare100% (1)

- Sgs Thomson Microelectronics An682 - E02f617b83 PDFDocument16 pagesSgs Thomson Microelectronics An682 - E02f617b83 PDFDaleycer Aono Tsukune-sanNo ratings yet

- FireBeetle Board-ESP32 User Manual UpdateDocument49 pagesFireBeetle Board-ESP32 User Manual UpdateARS IoT TeamNo ratings yet

- Europass CVDocument2 pagesEuropass CVSudaisKhanNo ratings yet

- M.tech. (VLSI Design)Document40 pagesM.tech. (VLSI Design)Manjunath AchariNo ratings yet

- Maintenance Guide: SINO Series Electrolyte AnalyzerDocument18 pagesMaintenance Guide: SINO Series Electrolyte AnalyzerRoniiNo ratings yet

- Tracing Current-Voltage Curve of Solar Panel BasedDocument8 pagesTracing Current-Voltage Curve of Solar Panel BasedMihai BogdanNo ratings yet