Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article 13

Uploaded by

J lodhiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article 13

Uploaded by

J lodhiCopyright:

Available Formats

SUMMARY

Machines, it seems, can do almost anything human beings can. Now cars are even starting to drive

themselves. What does that mean for business and employment? Will any jobs be left for people?

Will machines take over not just low-skilled tasks but high-skilled ones too? If a man and a machine

work side by side, which one will make the decisions? These are some of the questions facing

companies, industries, and economies as digital technologies transform business.

In this interview with HBR editor Amy Bernstein and editor at large Anand Raman, Brynjolfsson

and McAfee explain that while digital technologies will help economies grow faster, not everyone

will benefit equally—as the latest data already shows. Compared with the Industrial Revolution,

digital technologies are more likely to create winner-take-all markets. Brynjolfsson and McAfee

also believe that despite the heady pace of technological development, business dynamism has

dipped, and they worry that the policy response has been inadequate. They conclude that though no

one knows what the future holds, the time to start tackling the economic downside of new

technologies is now.

LEARNING:

Today’s digital innovations are doing for brainpower what the steam engine, and related,

technologies did for muscle power during the Industrial Revolution. They’re allowing us to

rapidly overcome limitations and open up new frontiers, say Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew

McAfee, who have studied the impact of technologies on economies for years. The two MIT

professors believe this transformation will create abundance. But they warn that there may be a

dark side: Though the pie will get bigger, not everyone will benefit equally.

As computers get more powerful, companies have less need for some kinds of workers. That

shift is contributing to a phenomenon the two academics call the Great Decoupling: For decades,

per capita GDP, productivity, private employment, and median family income rose in almost

perfect lockstep. But in the 1980s, growth in income began to sputter and then began to drop.

Adjusting for inflation, the median U.S. household today earns less than the median in 1998 did.

Job growth has also slowed. Similar trends are emerging in most developed countries.

In this interview, Brynjolfsson and McAfee explore the implications: who will win (workers with

tech and creative skills), who will lose (the middle class), and how business should respond to

the coming tech surge (develop ways to race with machines, not against them).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Susana Bloch - Alba Emoting Method PDFDocument19 pagesSusana Bloch - Alba Emoting Method PDFPatrick Sampaio100% (1)

- Diaphragms Chords CollectorsDocument219 pagesDiaphragms Chords CollectorsElio Saldaña100% (2)

- Ffe Lsa 30 July 09Document1 pageFfe Lsa 30 July 09Drago DragicNo ratings yet

- Tom Gates: Excellent Excuses (And Other Good Stuff) Chapter SamplerDocument39 pagesTom Gates: Excellent Excuses (And Other Good Stuff) Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press75% (76)

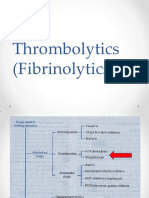

- Thrombolytics (Fibrinolytics)Document14 pagesThrombolytics (Fibrinolytics)J lodhiNo ratings yet

- Obstacles To Economic Development in PakistanDocument28 pagesObstacles To Economic Development in PakistanJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Public FinanceDocument9 pagesIntroduction To Public FinanceJ lodhi50% (2)

- FDI in Pakistan: Trend, Challenges, and ProspectsDocument21 pagesFDI in Pakistan: Trend, Challenges, and ProspectsJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Budgetary Policy of PakistanDocument8 pagesBudgetary Policy of PakistanJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- China Pakistan Economic CorridorDocument16 pagesChina Pakistan Economic CorridorJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- RM Lecture 3aDocument3 pagesRM Lecture 3aJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Why Managers Need To Know About Research: Examples of Applied ResearchDocument2 pagesWhy Managers Need To Know About Research: Examples of Applied ResearchJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Refining Research Ideas: Examining Own Strengths and InterestsDocument2 pagesRefining Research Ideas: Examining Own Strengths and InterestsJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- The Broad Problem Area: Causes and Not Symptoms of These CausesDocument2 pagesThe Broad Problem Area: Causes and Not Symptoms of These CausesJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis DevelopmentDocument5 pagesTheoretical Framework and Hypothesis DevelopmentJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Hypothetico Deductive MethodDocument27 pagesHypothetico Deductive MethodJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Applied Research EgsDocument4 pagesApplied Research EgsJ lodhiNo ratings yet

- Environmental AuditsDocument3 pagesEnvironmental AuditsSailaja Sankar SahooNo ratings yet

- Astm B505Document7 pagesAstm B505Syed Shoaib RazaNo ratings yet

- Lake Limboto in Climate ChangeDocument3 pagesLake Limboto in Climate ChangedonskayNo ratings yet

- Slewing Bearing Slewing Ring Slewing Gear Swing CircleDocument15 pagesSlewing Bearing Slewing Ring Slewing Gear Swing Circlezczc32z5No ratings yet

- Relative and Absolute Dating PDFDocument192 pagesRelative and Absolute Dating PDFPeeyush Kumar0% (1)

- Seminar WorkshopDocument25 pagesSeminar WorkshopComputer Science Department Bishop Chulaparambil Memorial CollegeNo ratings yet

- An X-Bar Theoretic AccountDocument14 pagesAn X-Bar Theoretic AccountSamuel Ekpo100% (1)

- Textual VariantsDocument1 pageTextual VariantsSean TitensorNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology Scheme of WorkDocument4 pagesMinistry of Education, Science and Technology Scheme of WorkJaphet AlphaxadNo ratings yet

- HydraulicDocument8 pagesHydraulicOsama OmayerNo ratings yet

- R - KE13N Upload of COPA Offline PlanningDocument10 pagesR - KE13N Upload of COPA Offline PlanningBenjamin AnbarasuNo ratings yet

- Paper P-1.p65-1Document33 pagesPaper P-1.p65-1SantoshNo ratings yet

- McDonalds V EasterbrookDocument18 pagesMcDonalds V EasterbrookCrainsChicagoBusinessNo ratings yet

- Bush (Brand) : Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument3 pagesBush (Brand) : Jump To Navigationjump To SearchirfanmNo ratings yet

- ISOM 2600: Introduction To Business AnalyticsDocument2 pagesISOM 2600: Introduction To Business AnalyticsHo Ming ChoNo ratings yet

- The Last Lesson NotesDocument11 pagesThe Last Lesson NotesAnvi Sameer TiwariNo ratings yet

- Rcm&E 202201Document100 pagesRcm&E 202201Martijn HinfelaarNo ratings yet

- PIA B2 - Module 2 (PHYSICS) SubModule 2.2 (Mechanics) FinalDocument82 pagesPIA B2 - Module 2 (PHYSICS) SubModule 2.2 (Mechanics) Finalsamarrana1234679No ratings yet

- Manual16 Hayward PoolDocument1 pageManual16 Hayward PoolAhmed FaroukNo ratings yet

- Cooking Show RubricDocument1 pageCooking Show RubricAna RivadeneiraNo ratings yet

- Tip#5) - Some Cool SCANF Tricks: Find Out Some of The Unheard Scanf Tricks That You Must KnowDocument17 pagesTip#5) - Some Cool SCANF Tricks: Find Out Some of The Unheard Scanf Tricks That You Must KnowGauri BansalNo ratings yet

- Movie Review: 3 IdiotsDocument2 pagesMovie Review: 3 IdiotsRachel CalaunanNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of International SocietyDocument6 pagesThe Evolution of International SocietyZain AliNo ratings yet

- Data TypesDocument29 pagesData TypesVc SekharNo ratings yet

- ATA24 Bombardier q400 Electrical PowerDocument85 pagesATA24 Bombardier q400 Electrical PowerAbiyot AderieNo ratings yet

- Sector Trading StrategiesDocument16 pagesSector Trading Strategiesfernando_zapata_41100% (1)